Burns the European

Share

- Details

- Transcript

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

Why was Burns so important to Robert Schumann? Why did they love him in 19th century Russia, but not in France? What is the wider musical legacy of Scotland's greatest poet.

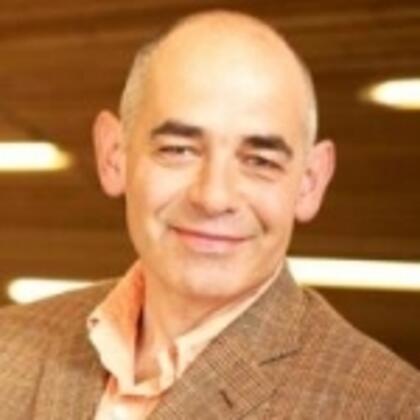

Often thought of as the quintessential Scottish poet, whose 250th anniversary is this year, Robert Burns' musical legacy is arguably as significant as his poetic one. Iain Burnside - pianist, Sony Award-winning broadcaster and professor at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama - ponders Burns within the context of European music.

Download Transcript

Burns the European

Iain Burnside

Seeing this lecture advertised in the Festival's splendid programme makes me realise that some of you may have been drawn here under false pretences. This resonant title BURNS THE EUROPEAN, which seemed such a good idea at the time, could suggest that I'll be dealing with how Burns fitted into patterns of 18th century European thought or politics.

Well, I'm afraid that's pretty much what this lecture isn't. If you'd like to leave now, I won't be offended. As a pianist and music broadcaster what interests me is how Burns was taken up by classical composers: what the Romantics made of him; why they were drawn to him. In a broader sense, inspired by the themes of these COLF celebrations, I'd also like to ask why German composers, in particular, chose to look North, to Scotland, as well as South, to Italy and Spain; and I'd like to explore what sort of Scotland they found there.

If you'd indulge me, I'd like to take as my starting point 2 stories, from my student days in the early 1980s. I was living in Warsaw, on a Polish gvt scholarship, receiving 2 gruelling piano lessons a week from a very old, very small woman, a distinguished professor at the Chopin Academy. It was in the nature of my lessons that they were free from any small talk. But one day towards the end of my stay there, before I was dispatched to learn yet more knuckle-busting studies, we had what can only be described as a chat. So it's Scotland you're from, she said. Yes. How marvellous. I am coming towards the end of my 2nd re-reading of the complete novels of your Sir Walter Scott.

Let me say that again, 2nd re-reading. Can anyone in this room look me in the eye and say they've read, once, even half the novels of Walter Scott? Again, towards the end of my stay in Warsaw I had the opportunity of spending a weekend in Budapest, and very pleasant it was too. Through the freemasonry of Eastern European students I was being put up by a friend of a friend, who announced that we'd be going for Sunday lunch to his parents. Which is how I ended up in a wonderful high ceilinged pre-war Budapest apartment, full of dark heavy furniture and faded velvet curtains.

The friend of the friend put a glass of plum brandy into my hands and went to help with lunch, leaving me alone with the 85 yr old grandfather. Oh, he said and Grandad only speaks German. So there we were, slightly awkwardly, me with my schoolboy German, this older gentleman with his rather better Hungarian equivalent. He apologised graciously for not being able to speak English. We learnt a little at school, he said, but it's so long ago. The only thing I remember is a bit of a poem, and I haven't the faintest idea what it means. And in his scratchy voice, he then slowly said:

My heart's in the Highlands, my heart is not here, My heart's in the Highlands a-chasing the deer.

It was a very touching moment. And it's no coincidence that this was the poem he'd been taught at school. As we'll see later, My heart's in the Highlands is for our purposes a key text.

So let's go back from 1980 to 1840, from My heart's in the Highlands to

Mein Herz ist im Hochland, Mein Herz ist nicht hier; Mein Herz ist im Hochland Im Waldes Revier;

The poem has been translated into German by one Wilhelm Gerhard, and here it is set to music by Robert Schumann. You might like to notice that Gerhard keeps Burns's metre. You could, if you chose, sing the original - it fits fine.

MUSIC SCHUMANN HOCHLANDERS ABSCHIED DG DFD t34 d1.24

Title - Highlander's Farewell.

Burns was a hugely important poet to Schumann - in numerical terms, his 2nd favourite. It's a childish way to look at it, perhaps, but the fact remains that the only poet Schumann set more often than Burns was Heinrich Heine, the poet of his Dichterliebe, and the Liederkreis op 24.

That song's one of 8 Burns settings published in 1840, as part of Schumann's anthology of 26 songs, Myrthen, Myrtles. And what an anthology! Myrthen was Schumann's wedding present to his bride Clara, a collection of pieces dripping with personal significance - full of secrets, in-jokes, private symbolism. There are 26 songs, one for each letter of the alphabet, and all the way through Schumann sets puzzles for his wife to decode, puzzles that WE're still decoding nearly 2 centuries later.

Not that these mysteries run deep in most of the Burns settings. To reach the altar Robert and Clara had come through a period of enforced separation, an irate father and a court case. So, as well as traditional lovesongs, we have variations on the theme of an die ferne Geliebte, songs about seperation. And in anticipation of Clara's imminent role as mother ' a hardworking, multi tasking, concert pianist mother - Schumann includes a lullaby. Burns's Hee Balou becomes HOCHLANDISCHES WIEGENLIED.

MUSIC SCHUMANN HOCHLANDISCHES WIEGENLIED CHANDOS T14 OUT AT 0.48

Robert Schumann writing music for his wife Clara to sing, or play, or both. It's a lovely tune and a charming song. As a Burns setting though I have to wag my finger, and award it low marks. Not for the only time, Schumann irons out Burns's agenda to impose his own.

Hee Balou, my sweet wee Donald, Picture o' the great Clanronald! Brawlie kens our wanton Chief What gat my young Highland thief.

Yes, it's a lullaby, but a cheeky one. And who's the daddy now? Why, the Lord of the Manor up the road. It's a poem as full of wry class tension as the Marriage of Figaro, and potentially as subversive. But we don't want illegitmacy in a wedding present, do we? So Clara Schumann gets to rock the cradle, serene and untroubled, instead.

The Battle of Culloden makes an unlikely appearance in Schumann's wedding present, in what has up to that point been a strapping lovesong, The Highland Widow.

For Donald was the brawest man, And Donald he was mine. Till Charlie Stewart cam at last, Sae far to set us free; My Donald's arm was wanted then, For Scotland and for me.

Schumann has no interest at all in Charlie Stewart. He's Donald, the big strong Scottish hero, the hammer thrower from the Quaker Porridge Oats packet.

And Charlie Stewart, Bonnie Prince Charlie, is the cause of the biggest misreading in this collection, the song Jemand, Somebody.

My heart is sair, I daurna tell, My heart is sair for somebody, I could wake a winter's night, For the sake o' somebody,

This is a political poem, where the exiled Charles Stewart can't be mentioned by name.

Ye powers that smile on virtuous love, Oh! sweetly smile on somebody; Frae ilka danger keep him free, And send me safe my somebody.

Had Schumann any inkling of this? I doubt it. By the time Herr Gerhard had turned this into admirable German, there was no reason to see this poem as anything other than, oh darling, I'm missing you terribly. Something that suited Schumann's purposes to perfection, and that prompts from him music of great inward beauty. It's the first Burns song in the collection, coming after that jewel in the crown, Der Nussbaum.

MUSIC SCHUMANN JEMAND CHANDOS T4 out at 0.50

One of the central paradoxes of Burns is this: despite his huge personality, he had chameleon elements - the ability to be what people wanted him to be. After his death, his poetry took on elements of this, too, as we can see from Schumann there, taking from the poet exactly what he needed.

Clara Schumann is more than a bit player in this story. I've given Clara a song by Burns to compose, Robert writes in the marriage diary he shared with his wife, at the end of September 1840 . But she doesn't dare do it. Well, wrong. She did indeed dare, but was keeping it secret so she could put it in Robert's Xmas stocking, at the end of his year of song, 1840.

Looking back with 21st c eyes it's astonishing that a husband should give this poem, unironically, to his wife as her composition homework - offering it up as a template for her emotions.

Musing on the roaring ocean Which divides my love and me; Wearying Heaven in warm devotion, For his weal where'er he be;

Hope and fear's alternate billow Yielding late to nature's law; Whispering spirits round my pillow Talk of him that 's far awa.

MUSIC CLARA SCHUMANN AM STRANDE HYPERION T18 out at 1.17

'In the dark and unusual key of E flat minor.

What interests me here is this. For all that Robert Schumann set Burns often, the songs are not among his greatest. That setting by Clara, on the other hand, represents a peak within her much more limited output. She was painfully modest about her composing talents, and wrote not a note after Robert died.

Which leads me to the first of several asides I'd like to lay before you, several fantasy

OH IF ONLY moments. The first is this:

Oh if only Clara Schumann had had a single feminist bone in her body and had read Burns, seriously, for herself, rather than waiting for her husband to tell her which poem she should be working on. Then perhaps she could have found a stronger Burns woman, a different woman's voice, and with it something more important to say.

O wha my babie clouts will buy, that great lyric written in the voice of Jean Armour, an unmarried mother wondering who'll be buying the baby clothes by day, and who'll fulfil her needs by night. Now, a Clara Schumann setting of that would really be worth hearing. Not only did Clara give birth to 8 children herself, she was also the one buying the babie clouts, through her concert fees.

Wha will crack to me my lane, the poem goes on. Wha will mak me fidgin fain; Wha will kiss me o'er again

If Clara Schumann ever asked herself those questions as her husband lay dying in the asylum in Endenich, the answer was clear, with handsome young Johannes Brahms comforting her, in a classic triangular situation loaded with unresolved sexual tension. So we shouldn't be surprised that Brahms caught the Burns bug, too, though we have to dig a little deeper to find it.

His opus 1 is a piano sonata, young man's music, full of ardour - written in 1853, the year Brahms, aged 20, entered the Schumanns' life. The last movement is a swashbuckling rondo, its main theme a sort of C major swordfight. The first episode seems to introduce some love interest. While for the 2nd episode in this sword fight, what should we get but our old friend My heart's in the Highlands. You might want to sing along, when the tune makes its dashing, kilted entrance.

MUSIC BRAHMS PIANO SONATA in C /4 DG t4 IN 2.52 out 4.40 D1.48

Burns's poem being treated first lyrically, then symphonically, then heroically. While the poetic impulse here clearly came via Brahms's mentor Robert Schumann, there was musical inspiration from a different source. Both Brahms's tune and one of his crunchier harmonies are heavily influenced by - some might even say pinched from - Mendelssohn's Scottish Symphony, published a decade earlier.

Here's the opening. Imagine the Brahms you've just heard slowed down to 16 rpm, and then orchestrated. Even the key's the same.

MUSIC MENDELSSOHN SCOTTISH SYMPHONY NIMBUS T1 OUT AT 1

The big difference between Mendelssohn and virtually all the other composers I'm talking about today is this: together with his friend Klingemann, Mendelssohn actually went there. His Scotland wasn't just a Romanticised fantasy, he got his feet wet in 1829, as he went from Glasgow to Inveraray; from Oban on to Tobermory, Staffa and then Iona. We can track his progress from his letters home, and from the exquisite drawings he made along the way.

In fact, as with so many Scottish holidays, it was more than his feet that Mendelssohn got wet.

We've had weather to make trees and rocks crash, he writes home. The newspapers have been full of the rain. I've invented a new way of drawing specially for it, by rubbing in the clouds, and painting grey mountains with my pencil.

Mendelssohn's travels bring in 2 figures that are part of our bigger story. At his mother's insistence, he made the long trip south to Abbotsford in the Borders, to call on the ageing Sir Walter Scott. The visit was a disaster. Scott doesn't seem to have had any idea who these 2 Germans were, knocking on his door. We drove 80 miles and lost a day,Mendelssohn writes, for one half hour of superficial conversation.

The point though is Scott's celebrity. Not only was he a writer of European fame; in 1829, 3 years before his death, Scott had already put Scotland on the musical map. Schubert had written his songs from The Lady of the Lake; Rossini had composed La Donna del Lago. In France Boieldieu's opera La Dame Blanche was based on Guy Mannering; and in that same year of 1829 Paris saw the premiere of Carafa's Le Nozze de Lammermoor - to be overshadowed forever just 6 years later by Donizetti's Lucia.

Walter Scott was a musical treasure trove within his own lifetime, his landscapes and noble characters fuelling the European imagination. That imagination, though, had already been engaged by an earlier writer - to all intents and purposes much earlier, the Celtic bard Ossian. It was ultimately because of Ossian's epic Gaelic poems, with their strapping hero Fingal, that Mendelssohn found himself in the Inner Hebrides, seasick on the little steamer Ben Lomond, bound for Fingal's Cave.

The Hebrides Overture is far from being the only bit of Fingalabilia we have. Indeed Mendelssohn's masterly Overture has probably less to do with Fingal's Cave than we've been led to believe. But the character of Fingal was taken completely seriously - first by Schubert, and then later by Brahms.

MUSIC BRAHMS GESANG AUS FINGAL PHILLIPS T22 out 1.28

keep on the rocks of roaring winds, O maid of Inistore! He is fallen! Thy youth is low, Pale beneath the sword of Cuthullin!

In 1760 the canny young poet James Macpherson brought out Fragments of Ancient Poetry collected in the Highlands of Scotland, claiming in the following year to have found Ossian's epic Fingal. It was all an enormous ruse - Macpherson doing some skilful pastiche work and fooling the entire literary establishment, for a while, at least.

The Western Isles were at this point hugely inaccessible. So next to the image of Mendelssohn struggling out to Staffa on the Ben Lomond, consider this: Scott and Keats had both done it just before; Wordsworth and Turner would do it just after.

Looking back now, there is much here to astonish. For a start, it all seems such terrible poetry. But this so-called Scottish Homer fooled Walter Scott, and he fooled Goethe. He inspired Ingres to paint Ossian's Dream. And through translations by Goethe's friend Johann Herder, Ossian joined a body of Scottish balladeers, etching storm-tossed cliffs and ruined castles into received opinion as one definitive image of Scotland.

Balancing the Ossian view of Scotsman as Noble Savage was a more genteel 18th c perspective: from the Edinburgh drawing room. Which takes us back to Burns.

MUSIC HAYDN BONNIE WEE THING ORFEO T3 OUT AT 0.54

b/a' arr JH

Arranged is not a word I've used so far. All the Burns settings I've played you up to this point are, to use shorthand, art songs rather than folksong arrangements. This shorthand is useful, but deceptive too: the reality is more complicated, and indeed more interesting.

'At present I have time for nothing, Burns wrote in 1788, when he started working on James Johnson's Scot's Musical Museum. Dissipation and business engross every moment. I am engaged in assisting an honest Scots Enthusiast, a friend of mine, an Engraver, who has taken it into his head to publish a collection of all our songs set to music, of which the words and music are done by Scotsmen. This, you will easily guess, is an undertaking exactly to my taste.'

The interconnection here between words and music, who wrote what, when and why, is a topic big enough for another whole lecture. Were Burns's poems poems first, or songs? Are they the chickens or the eggs? The answer varies from piece to piece.

The European angle here comes in the 1790s, from the Edinburgh publisher George Thompson, who had the wit to look further afield for musical talent, to enrich his Select Scottish Airs. It's to Thomson that we owe this piano trio texture, a winner for domestic sales, where Mum playing the violin can keep Dad on the straight and narrow if he has trouble singing the tune.

Thomson's initial letter, pitching to Burns to join his team, sets out his stall:

For some years past, I have, with a friend or two, employed many leisure hours in collating and collecting the most favourite of our national melodies, for publication. We have engaged Pleyel, the most agreeable composer living, to put accompaniments to these, and also to compose an instrumental prelude and conclusion to each air.... To render this work perfect, we are desirous to have the poetry improved wherever it seems unworthy of the music.... Some charming melodies are united to mere nonsense and doggerel, while others are accommodated with rhymes so loose and indelicate as cannot be sung in decent company.

To Pleyel were eventually added the big hitters: Haydn, Weber and Beethoven, together with the less celebrated Bohemian Leopold Kozeluch.

Looking now at all these trio arrangements needs a certain detachment - I find it hard to see the glass as being a quarter full , rather than 3 quarters empty. Because for the most part they were money spinners for these great composers, in a severely limited, severly limiting, genre.

Haydn comes out best, I think, his music springing to life when there's a personal connection. Haydn was unhappily married - Mrs Haydn and he were totally incompatible. At least Burns gives him license to laugh at it.

MUSIC HAYDN MY LOVE SHE'S BUT A LASSIE YET ORFEO T24 IN AT 1.17 TO END D1

b/a

If Beethoven's arrangements of Burns are disappointing, it's partly because our expectations are so high.

Which leads me to my 2nd IF ONLY aside. If only a good translation of Burns's more important poems had reached Beethoven, the fusion of these 2 imaginations could have been spectacular. Beethoven setting A man's a man for a' that' I'd buy a copy'.

Which leads me rapidly to my 3rd IF ONLY aside. If only that same translation had reached Mozart, a decade earlier. The dates just about work - among the musical greats it's Mozart who was Burns' nearest contemporary. Their senses of humour were not dissimilar; they were both skilled at charming their social superiors, and charming the girls; they were both enthusiastic Freemasons.

I'm conscious now that in addressing these musical greats I'm giving a lopsided view of Burns settings. Were there recordings available of Robert Franz's Scottish songs, then later those of Adolf Jensen, Max Bruch or Karl Reinicke., I'd be happy to play them to you. Instead let me simply plug my recital with AK in Goldsmith's Hall, on Wed!

The Jensen songs in particular have been a revelation to me. I didn't know his work before but the twinkle in his eye makes him a Burns natural. I specially like a song called Einen schlimmen Weg ging gestern ich, using Burns's poem The Blue Eyed Lassie.

I first of all like it because Jensen's heart isn't in the highlands, and neither is his love like a red, red rose. Burns's focus is his sweetheart's eyes:

'Twas not her golden ringlets bright, Her lips like roses wat wi' dew, Her heaving bosom lily-white: It was her een sae bonie blue.

Jensen though has his own ideas. When he comes to the girl's heaving bosom, a huge ritardando, swelling chromatic harmony and a delicious, lecherous turn of phrase suggest that the eyes may have competition. Then later when the piano postlude trips off merrily in thirds, Jensen seems to be telling us through the vocabulary of Lieder pianism, that all good things come in pairs. How Burns would have approved.

Now that's enough of Burns in Germany. What about France?

MUSIC RAVEL CHANSON ECOSSAISE NAXOS T3 OUT 1.36ish

b/a '.Albanian soprano'.

We've jumped on into the 20th c now, but jumped back in genre to the arrangement of a traditional tune. Though what an arrangement - Ravel there deceptively simple, showing how less can be so much more, his simple harmony exquisitely voiced, his little touches of bagpipe drone, remarkably, unembarrassing. Even unpatronising.

You will look in vain for a French artsong tradition that engages with Robert Burns; they simply weren't interested. But there is one intriguing carry over, again into the world of solo piano music.

MUSIC DEBUSSY LA FILLE AUX CHEVEUX DE LIN DECCA T11 OUT 1.18

b/a The girl with flaxen hair

Ostensibly the title comes from a poem by the 19th c French poet Leconte de Lisle. Dig a little deeper and you find that Leconte de Lisle was very Scotland-friendly, an admirer of both Burns and Scott, and this girl of his is Burns's Lassie wi'the lint-white locks.

So beautiful is this poem, a shepherd addressing his sweetheart, that I'm amazed it doesn't crop up in the Burns Top 10, but, well, it doesn't. I'm going to read you the end of the poem and then play you the end of the Prelude, so you can see how faithful Debussy is to Burns. It's really a song without words. And that opening tune you just heard - it's not the girl's wavy hair, as has often been suggested, it's the shepherd wistfully blowing his little pipe

When Cynthia lights, wi' silver ray, The weary shearer's hameward way, Thro' yellow waving fields we'll stray, And talk o' love, my Dearie, O.

And when the howling wintry blast Disturbs my Lassie's midnight rest, Enclasped to my faithfu' breast, I'll comfort thee, my Dearie, O.

Lassie wi'the lint-white locks, Bonie lassie, artless lassie, Wilt thou wi' me tent the flocks, Wilt thou be my Dearie, O'

MUSIC DEBUSSY LA FILLE AUX CHEVEUX DE LIN DECCA T11 IN 1.33 OUT END D1.22

Now, having brought up earlier Burns's huge popularity in Eastern Europe it's time to turn our attention to Russia. Burns was mentioned favourably in despatches by Pushkin and Turgenev, and adored there by the pre-revolutionary literati. Come the Soviet era, though, and the balloon really goes up. A man's a man for a that is claimed as a hymn to communist values and Burns is hailed as the people's poet, the peasant hero, the horny handed son of toil made good. 50 years ago, to mark the 200th anniversary of his birth, Burns is given the supreme accolade ' a Soviet postage stamp is issued with his face on it. The boy's come a long way from all those shortbread tins.

Of course it's 90% tosh, as partial a reflection Burns's complexities and contradictions as those shortbread tins on sale in Scottish gift shops. What intrigues me though is how serious some 20th c Russian artists were about Burns, and how they took from him what they needed, just as the 19th c Germans had.

So we find Shostakovich setting Macpherson's Farewell. James Macpherson was a 17th c outlaw, immortalised by Burns for dancing in the face of death, doing a defiant jig the night before he faced the gallows.

For Shostakovich in 1942 to share Macpherson's gesture but not his fate, he had to code defiance though music.

Untie these bands from off my hands And bring to me my sword! And there's no a man in all Scotland But I'll brave him at a word.

MUSIC SHOSTAKOVICH MACPHERSON'S FAREWELL TOCCATA T13 OUT 1.08

DS, raising 2 fingers at Stalin.

The companion piece to this is a song written for Shostakovich's wife, a dark, restrained setting of O wert thou in the cauld blast. To protect you from the cold, the poem says, to shield you from Misfortune's bitter storms, I'd put my plaidie round you

And just as Ravel earlier hinted at the cliché of the Scottish drone, so we have an echo here in the empty 5ths of the LH, moving up and down. Was there ever a colder blast than the Siege of Leningrad? Did Misfortune's storms come any more bitter?

MUSIC SHOSTAKOVICH O WERT THOU IN THE CAULD BLAST TOCCATA T12 OUT 1.19

The collection that these songs come in puts Burns next to Shakespeare and Walter Raleigh. It's also significant that Shostakovich quotes these songs in his 13th symphony, Baba Yar - its subject, the Holocaust.

This recording comes from a fascinating Cd of Soviet Burns settings just out on the ever enterprising Toccata label. Among its many virtues is this: not only does it give you the Burns poem and its Russian translation, it gives you a translation of the translation. In other words, we get back what the Russian really means. And if this sounds like an exercise in smoke and mirrors, here' what one of the Russian Top 10 Artsong texts really says:

Love like a red rose blooms in my garden My love is like the song that cheers me on my way. Greater than your beauty is my love for you, dear, And will be with you always. Till the seas run dry, my dear. Farewell, farewell, farewell!

I'm not trying to make fun of the translator here - far from it; I merely draw your attention to the process.

Here' another example, a song by Tikhon Khrennikov called A Toast, and although it' the wrong time of year for his toast I reckon you'll be able to work out the original. This is the backwards translation:

Should we forget and not regret old love when brought to mind' Should we forget the friendships made in times so long ago? We'll drink to bygone fellowship ' to the bottom of the glass. And you and I, old friend, will drink to happy days gone by.

MUSIC KHRENNIKOV A TOAST TOCCATA T20 OUT 0.48

b/a .. waltz'Auld Lang Syne

Post-Soviet music now, from the Baltic. When I first heard Burns set by Arvo Part I had to smile at the incongruity of it. Could there be more unlikely bedfellows than Burns and this austere Estonian? I don't see the earnest, bearded Part as a candidate for what Burns called rakery. And neither in this piece does he prove a natural huntsman.

Because yes, this is our final setting of My heart' in the Highlands, and one unlike any other. The hunting agenda is irrelevant here - Part focuses entirely on loss, and the poem becomes an elegy, a study in alienation.

MUSIC ARVO PART MY HEART' IN THE HIGHLANDS DELPHIAN t8 OUT AT 1.57

After a while, the organ there takes on a bagpipe quality. I suppose they work on the same principle: a pipe' a pipe, for a' that.

My last foreign country is England. And I come to it with low expectations. Why should one expect the English song tradition to take on board a poet who so defines another nation? I can give out honorable mentions- stand up Quilter, Parry, Somervell, Grainger and Hurlstone; and I can certainly give a huge gold star to Malcolm Arnold, for his enterprising, entertaining orchestral tone poem Tam O'hanter.

What though is a Scotsman to make of Benjamin Britten and his Birthday Hansel, 7 Burns poems sewn together, for the tenor Peter Pears and the harpist Osian Ellis to sing as part of the Queen Mother' 75th birthday celebrations? It' a piece towards which I've always felt ambivalent. I'm not a big royalist, so must confess to being deeply turned off by the Queen mum connection. And then there' the language issue, with Peter Pears going all Ayrshire, the Scottish equivalent of blacking up to sing a Negro spiritual.

On the credit side though is plenty - most notably the skill with which Britten first chooses his poems, then sets them, then weaves them together: turning this Hansel, this posy, into a single continuous span of music, unlike anything else in the repertoire. And for the lyrical songs, Britten finds a voice of disarming simplicity. Here' a more recent rec than PP, a soprano. Not Albanian this time but Canadian.

MUSIC BRITTEN A BIRTHDAY HANSEL CHANDOS T11 out at 1.23

In a lecture dealing with songs I suppose I shouldn't be surprised that lyric poems have been favoured to the exclusion of all others. But even so it' striking how one-dimensional the picture of Burns is, emerging through the music I've played you. There' very little sense of Burns the iconoclast, the satirist, the politician. And precious few glimmers, all in all, of his sense of humour.

The last of my IF ONLY asides, and the most heartfelt, takes me back to the German language, and to 19th c.Vienna. If only Hugo Wolf had discovered Burns. Alone of the Lieder greats Wolf had the vocabulary and experience to do Burns full justice. Wolf' songs tick most of the boxes I've just mentioned and a few more besides: he can be funny, tender, affectionate, scathing; he does songs about booze; about religious cant. In Wolf' Feuerreiter, he even has a demonic galloping horse. He really could have taken on Tam o Shanter. A Wolf Schottisches Liederbuch - now you're talking.

For my last music I'm going home to Scotland. It' the most recent music too, from James MacMillan, a magical choral setting of Burns' Gallant Weaver. Why have more composers not looked at this poem? Its subject matter is explored in folk songs, art songs, Lieder and French melodies; in Country and Western songs. My parents want me to marry the clean living well-off boys, this girl sings; but I've lost my heart to the poor boy, to my gallant weaver.

MUSIC JAMES MACMILLAN THE GALLANT WEAVER DELPHIAN T11 OUT AT 2.00

I love my gallant weaver, the alto sings. Macmillan here is taking the line out of context, using it earlier than it comes in the poem and turning it into a sort of refrain, making it almost filmic. He catches Burns' yearning quality to perfection.

So perhaps this is a good place to end ? with an Ayrshire born composer, a living composer who engages seriously with this great poet.

In June 1796, with less than 2 months to live, Burns wrote to James Johnson.

You may probably think that for some time past I have neglected you and your work; but, Alas, the hand of pain, and sorrow, and care has these many months lain heavy on me! Personal and domestic affliction have almost entirely banished that alacrity and life with which I used to woo the rural Muse of Scotia. In the meantime, let us finish what we have so well begun.

Burns didn't finish, by any means. But James McMillan there suggests that the rural Muse of Scotia has plenty of life left in her yet. Long may she flourish.

© Iain Burnside, 6July 2009

This event was on Mon, 06 Jul 2009

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login