Death Control: The Last Taboo? - 'Death Control' and 'Development of the UK's Longevity Market'

Share

- Details

- Transcript

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

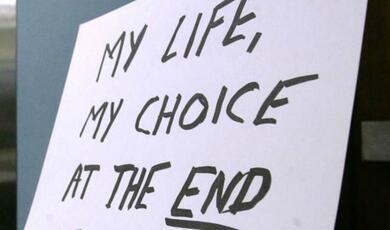

Euthanasia, whilst becoming a more frequent topic for comment in the Press, is still viewed with as much suspicion as eugenics a hundred years ago. Ethical issues, legal and financial questions are touched on but tend to provoke well-worn responses. This Symposium provides an opportunity for serious debate on this important topic.

This part of the symposium consists of the following talks:

Death Control: The Last Taboo - An Introduction by Professor Tim Connell

Death Control by Katherine Whitehorn

Development of the UK's Longevity Market by Rajeev Shah

Download Transcript

9 DECEMBER 2009

DEATH CONTROL: THE LAST TABOO

AN INTRODUCTION

PROFESSOR TIM CONNELL

May I begin by claiming no particular knowledge of today's subject. But increasing maturity has led to my becoming so much more familiar with old age, infirmity and death. Certainly, I attend more funerals these days than christenings. The attrition rate among the older generation (friends' parents, old neighbours, teachers and now colleagues) is running at the rate of about one a month and I pay closer attention to the obituary columns than I once did. One colleague of mine (who I don't get on with terribly well) said to me recently, 'I see you're writing obituaries for The Times now,' to which I replied (quite without thinking), 'Yes, and I'll write one for you any time you like.'

The greying of the population (there are now more people in this country over 65 than under 17), the social and financial cost of care for the elderly, the pensions scandal, even the debate on immigration, all contribute to make this a major issue that needs to be considered with care. Recent debates arising from the attempts over a three-year period to introduce an Assisted Dying Bill into the House of Lords range from the purely ethical to the fiercely practical, though there does seem to be a growing trend towards accepting the fact that keeping someone alive at all costs is probably not in anyone's interest. There have been comparisons with legislation in Holland, Oregon and parts of Switzerland, all of which serve to heighten awareness as to the sheer complexity (some would even say hopelessness) of finding a solution to the problem of longevity which is just, ethical - and workable.

a) Death Control

So why Death Control, and why do I call it the Last Taboo?

A key topic for debate in the Twentieth Century revolved around birth control, from the controversial topic of eugenics to the more modern concept of family planning. Writers such as Somerset Maugham highlighted slum conditions through his best-selling first novel Liza of Lambeth of 1897, which was based on his experiences as a sixpenny doctor working out of St Thomas' Hospital. Marie Stopes caused enormous scandal with the publication of her first work Married Love or Love in Marriage in 1918, and which went through six editions in a fortnight. Although population growth has not followed the pathways predicted by the Reverend Malthus, population pressure has become a subject touching on a whole variety of areas, ranging from urban planning to climate change. The shift in the demographic balance in Western Europe now leaves most EU states with more inhabitants in or approaching retirement than going through school. This raises a different range of questions concerning education, employment, re-shaping of the social pyramid, and the underlying question as to how fewer people in work will be able to maintain more retired people who no longer work, and what is to be done about those whose lives can be prolonged because of advances in medicine, but who have no hope of recovery or even of leading a normal life.

Euthanasia, whilst becoming a more frequent topic for comment in the Press, is still viewed with as much suspicion as eugenics - and this was a concept which was given far more credence a hundred years ago than we would perhaps like to admit today. Ethical issues, such as the right to life versus the unnecessary prolonging of pain; legal questions such as assisted suicide; financial matters, such as the cost to both individuals and the State, are touched on but tend to provoke well-worn responses, which rarely lead to objective serious debate. Ironically, pre-natal testing, in vitro fertilisation, genetic counselling and genetic engineering can now be discussed in the way that compulsory sterilisation once could.

b) The Last Taboo

In many ways we have become hardened about death. Military losses in Afghanistan, the spate of fatal shootings and stabbings in London and elsewhere in the UK, the number of TV series that bring us full-frontal autopsies, all contrast strangely with the fact that death is no longer part of daily life as it was for the Victorians. The number of centenarians increases year by year as indeed does life expectancy (in the developed world at least) and as the baby boomers age, so will the number of dementia cases and patients requiring long-term hospital care with little chance of a proper recovery.

This in turn raises a number of ethical issues: will we have to ration medical services, or charge prices that will make them unobtainable to all but a fortunate and affluent few? Will national insurance contributions have to double if people are to be offered long-term care for possibly thirty years after they stopped full-time work? Will public attitudes and (in due course) the Law change so that living wills can have legal status, and will doctors be able to take life and death decisions in the way that they could before the Harold Shipman case? Can the Law protect the vulnerable whilst recognising that medical care can stop people from dying without enabling them to lead anything like a normal life? And will the economy be able to sustain the army of carers who will be needed to look after the legions of geriatric cases that are already anticipated?

Apart from legal and medical issues, what about the personal aspects of longevity? The financial pressure and burden or the family of terminally ill or dying relatives? Baroness Warnock has already raised the question of the impact on people's lives of having to give up work and make other long-term sacrifices in order to become carers - and been heavily criticised for it too. Equally, the individual at the end of their life must have rights too. Even the last few days, weeks or even hours may be of value, and being able to say goodbye properly, to tie up final loose ends and perhaps be seen to do things properly, may all be of enormous importance to friends and relatives as well as the person concerned. It was the ancient Chinese who said that your last task as a parent is to show your children how to die well.

These are questions which are facing us all now. It is commonplace today for people to retire and find themselves caring for elderly relatives. Problems faced by people in their forties or fifties even twenty years ago are now cropping up or persisting to a point where the elderly may well be caring for the positively aged, unless or until they are no longer able so to do. Bearing in mind the saying, "Get even with your kids - live long enough to be a real nuisance", it is quite possible that our children will have to pick up the tag as social costs for the elderly across Europe will double by the year 2060. Le Monde produced a supplement only last Saturday about caring for old age in France, which faces the prospect of caring for some two million people over the age of 85 by 2015. It is interesting to see that they are looking at insurance schemes (funded by the employer) which would begin at the age of 55, but the idea of being able to pay for care with 500 Euros a month seems optimistic, to say the least.

The other saying about getting even with the kids is - spend their inheritance. At my pre-retirement briefing I was told not to save my money, not least because all my savings could eventually be taken by the local health authority to pay for my place in the care home, apart from a token sum of £23,500 - and that will not cover the debts that will be incurred by the grandchildren going to university, or even help pay off the mortgage on the family home, which many people have anticipated doing from inherited family money. Equally, an elderly person who is worth more dead than alive needs a special sort of protection under law, which is now being provided by the Court of Family Protection. A report called 'safeguarding Adults' which came out last year, calculated that over 342,000 people are victims of some sort of abuse by carers or relatives in their own homes, ranging from misappropriating money being paid for care through to selling the house without the person's knowledge - and pocketing the proceeds.

Whether we like it or not, this is a subject we will all have to face up to sooner or later. Sooner because there are ethical, moral and legal issues which have to be faced up to. A number of high profile cases have brought to the fore the questions of euthanasia, living wills, assisted dying and the right to die. The matter is under debate in the press and the House of Lords.

We will have to face up to it later, as we in our turn have to come to terms with our own mortality. We prefer not to ask for whom the bell tolls, partly because medicine does offer so many more chances of survival, even with diseases that were fatal even a few years ago. Palliative care and advances in surgical procedures, equipment and anaesthetics make major operations and long-term treatment perhaps less daunting, and offer a higher degree of hope than ever before. "It is wonderful what they can do these days" is no longer a truism.

Even so, we feel increasingly uncomfortable as we see familiar names in obituaries or attend memorial services for contemporaries or, even worse, younger friends, relatives and colleagues - even if we have not yet reached the point, like Bill Deedes, who used to turn to the obituaries column of The Times first thing in the morning just to check that he was still alive.

Today we are fortunate to have a distinguished range of speakers who will be approaching the topic from a variety of angles: veteran journalist Katharine Whitehorn will be known to you all as a longstanding contributor to The Observer and whose thoughtful broadcast one Sunday morning on Radio 4 led to the inception of this Symposium; Richard Sorabji and Keith Ward are emeritus professors of the College; and Rajeev Shah will be able to put some figures onto this subject and hopefully make a few life insurance calculations for us as a graduate of LSE and a Fellow of the Institute of Actuaries.

Concluding remarks

As I indicated earlier, Death Control (or at the very least a sensible and workable set of policies and procedures to ease us all smoothly and comfortably out of this world) is a complex matter. I view the matter with increasing sense of urgency myself as I sometimes feel that I am in the early stages of the Charge of the Light Brigade, with the saddles around me beginning to empty, as the Class of 1968 begins to creep slowly and inexorably up the Obituary Page of the Queen's College Record.

The whole situation today regarding infirmity, old age and death is surrounded by doubt and shrouded in secrecy. My great-grandparents both came from large Victorian families where almost half the children died in infancy. (We have a family picture of my Uncle Walter, who died as a baby in the 1880s - and who had been dressed as an angel for one last photo.) Death was accommodated through publicly recognised ritual: the armbands and mourning clothes, jewellery made of jet for full mourning and amethyst for half-mourning; the lavish monuments and memorials in parish churches. Victorian cemeteries, like Highgate and Brompton Road, look like some ancient necropolis. The disposal of the dead in London became a major issue as the topic grew - there was even a special station adjacent to Waterloo linked to Brookwood cemetery in Surrey, and which operated between 1854 and 1941. Today we are more concerned with environmentally friendly coffins and the space taken up by graveyards which filled up decades ago and whose graves have long since been left untended as the bereaved have, in the fullness of time, followed the dear departed in their turn.

Benjamin Franklin said that there is nothing inevitable in this life, except for death and taxes, but in the same way that we are urged by Her Majesty's Revenue and Customs to think about the one, at some stage we all have to think about the other. Inevitably, that means that the medical, ethical and legal frameworks will have to be hammered out. This is quite understandably a delicate and difficult topic. The Royal College of Nursing's decision to take a neutral view on assisted suicide provoked a spate of letters and on-line comments to The Times, indicating that in many cases the battle lines are drawn before the matter has even been discussed. Even the National Council for Palliative Care has a web page to outline its views on Euthanasia and Assisted Dying.

We need an informed and dispassionate debate on all these life and death topics, and I hope that Gresham College, as a place for informed debate and consideration not only of new learning, but also new understanding, has been able to shed some light on this important, timely and in many ways, chilling, debate.

© Professor Tim Connell, 2009

9 DECEMBER 2009

DEATH CONTROL

KATHERINE WHITEHORN

"I used to envisage my deathbed. I would be lying back on my pillows, pale but brave, surrounded by a weeping family, and forgive all my enemies- on the grounds that nothing would annoy them more.

I now realise, of course, that the likeliest way for me to die is in a hospital or hospice with tubes coming out of my arms and nose, probably aching and demented, half awake at best; and what I might be thinking - if anything - I have no idea. Modern medicine can keep us alive for years and decades when we might once have died; and I don't think that our thinking has really caught up with the implications of this.

Our expectations of death have changed enormously, even I suspect in my lifetime. I notice that in The Times obituaries, if you're over 80 they don't say what you died of; over 80 it's not astonishing - but under 80 they usually say of cancer - of a heart attack - in an accident. We all know that we're living far longer; but the amazing ways in which medicine can cure us - or not cure us at least keep us going - has one unfortunate consequence; it's almost made us feel that to talk about what would be a good way to die is defeatist; we talk - or at any rate think - as if enough medical help can ward it off forever. I heard one nurse quoted "I regard any death as a defeat". It's as if the very success of medical help has made us almost deny the reality of death. Rather the way people will shy away from making a will "it means I'm going to die!" In the same way we talk of preventing death from cancer from heart attacks - we haven't, we just postponed it; my father, who smoked a pipe used to say "If you smoke you die of cancer; if you don't smoke you don't know what you die of!" The more you stop people dying of these killers, the more they are likely to live to the stage where you can hardly see, hardly hear, hardly remember... "I want to die peacefully like my father - not screaming in terror like his passengers" - but perhaps even the passengers weren't having the worst time of it... Maggie and Anthony Barker were two medical missionaries who, when they retired, would raise money for their hospital in South Africa by doing sponsored rides on a tandem bicycle. They had a marvellous party for their 80th birthday and set off on their last ride round Britain- and a lorry came round the corner and killed them outright. Everyone said How Dreadful- but it wasn't dreadful, no bereavement, no slow decline of faculties, no pain or dementia - it was a great way to go.

To my mind, the time has come when we have to rethink the whole question of death as we have entirely rethought the question of birth - And if the pro-lifers should say 'No we haven't we don't approve of adoption or birth control' you only have to point out that they don't usually object to all the equally 'unnatural' things we do to promote birth- IVF, early Caesareans if the foetus seems in danger, surrogate motherhood, donor inseminations, even intensive care for tiny premature babies who may not last at all, or not without great pain - all of which are legal, all of which need safeguards- as of course would any rethinking of our acceptance of responsibility over death. But whether we- as a nation or as individuals - care to use them or not, we do now have choices.

Of course there were always choices for some: soldiers who chose to stride into the heat of the battle rather than lurk behind a tree: Queen Jane, who got them to 'cut her side open and save my baby' Romans had a tradition of honourable suicide so of course have the Japanese; so, oddly enough, has Hungary. But our Christian tradition has not - I can't even remember which set of Maidens of the early church it was who were condemned, not praised, for flinging themselves over a cliff to avoid being raped.

The devout see this prohibition of suicide as a matter of waiting till God calls, not having views about it yourself; the cynical, that the lives of the underdogs in much of history were so awful that if people weren't threatened with hell fire if they ended their lives themselves they might well think death was a lot better than their ghastly lives - and then who'd be left to do the worst jobs and fight in the bloodiest battles? It's still used a prohibition against ending your own life: but I am not about to be impressed with a cleric who was on about waiting for Gods will when he had a pacemaker- clearly the Almighty might have wished to discontinue him much earlier, but he didn't mind thwarting his intention in that matter.

The simple fact of our times is that far more people have lives immeasurably prolonged by modern medicine, and the question of who should be allowed to die and how becomes unavoidable. Doctors, in the old days when Doctors Knew Best, often did help someone in pain out of this world, and in some places still do, but, since Shipman, British doctors hardly dare. That doesn't mean it was always a bad thing. I am reminded of an extract from Sam Gorovitz's book on medical ethics: a young man asked the doctor to give his agonized mother more painkiller, was told he couldn't because of addiction, and that it might repress her breathing. The young man accepted this at first, but then came back and said: 'Where is it written that the cancer has a right to be the cause of death? That the doctor's duty is to keep the patient alive until the tumour can cash in its claim?'

Currently, doctors are allowed to help you out of this world only if their prime object is to control your pain - which usually means morphine, not the simple glass of barbiturate that you can be offered in Holland or Oregon. Suicide has not been illegal since 1961 (and never in Scotland), so you're alright if you can still manage to do it yourself, though it's got a lot harder - no good putting your head in the gas oven, it's the wrong kind of gas, and though they once gave you barbiturates routinely for depression, you can't get hold of them anymore. As Dorothy Parker put it, 'Acids stain you Drugs cause cramp Razors pain you, rivers are damp Guns aren't lawful nooses give Gas smells awful - You might as well live'

People do, though, still manage to refuse the last ghastly stages of their illnesses. Bernard Levin, who had Alzheimer's, didn't eat during the last week of his life; Catherine Storr, the children's writer, used the plastic bag and pills method; Jill Tweedie the journalist had Motor Neurone disease, which is a horrible way to die; she got an infection and refused point blank to take any antibiotics.

But what about assisted suicide? There are several arguments against it, some seriously worrying, one or two entirely misconceived.

One is that if you have assisted suicide, it must mean placing less emphasis on palliative care. NOT SO. In Oregon (where palliative care is called 'hospice', it's not just a building because much of it is done at home) - Oregon's palliative care is rated the second best state in America.

The other is that all pain and misery of the terminally ill can be controlled with good palliative care. It just isn't so. Acute pain, maybe; but what about the misery of being totally paralysed? Of not being able to communicate at all? Yes, one man manages to do it by winking one eyelid- but it's so rare that his account of this becomes a best seller. What about dementia, with just enough occasional surfacing into consciousness to realise that the real self you are is already dead? When people use the phrase 'loss of dignity' you think it means not enjoying to have your nappy changed; in Bert Keiser's book Dancing with Mr D, he mentions someone who was vomiting their own faeces. Physical pain is not everything by any means.

But in the name of what do we put people through this? Kindness? It's not kind. Making sure nobody is killed by accident? That might be the least of our miseries. Upsetting grieving relatives? Are they really going to be more upset by watching crumbling old bitter relic replace the much loved husband or mother? On our last visit to my father in law Joe in his nursing home, his son and I came away saying 'If it was an animal you wouldn't let it go on' mercifully, he died the next day.

If it's in the name of religion, a view about Gods will - well, let it be confined to the religious. If it's to prevent malfeasance - that surely could be preventable. If it's to protect the professional ethic of medics - let them get a better ethic that relates to patients' needs and less to not getting sued or - lets be charitable about this - making a mistake and doing something for the patient that the patient did not, actually, want.

There are two serious doubts still remaining: that old people would think they really ought to ask for death rather than be a burden - but would that, actually, be any worse than having them writhe for months in pain or be sedated out of all consciousness? Those who approve of assisted suicide often tend to cite only the situation of someone who will die anyway in a few weeks or months, but that really isn't enough: if you thought your paralysed incapacity to talk or see, to move or control any of your functions was going to go on, day after day, month after month for years, you'd surely ache even more for release than if you only had to stick it for a few more weeks before nature would take its course. And 'being a burden' isn't just awful for a carer - I can think of few things worse than having to have my bottom wiped by my daughter in law.

And there is the question of whether, in this country, we would actually be efficient enough to make sure that every deliberate death was wanted and needed and fair: lots of things work in Holland that wouldn't- or don't- work here: co-living for elderly couples, or streets with no traffic lights. If we can't, here, make sure sometimes that a sick old lady gets her shitty sheets changed, can we be sure they'd get her wished right about something as important as her death? I'm not sure.

Whatever we ultimately decide is feasible, I think we must move away from conviction - sometimes an unconscious conviction - that any life is better than death, towards an honest realisation that we will all die, and that it would be good if we could have some choice about how it happens. Someone with whom I was discussing it all said that maybe the way that we treat our ailing elderly - or appalling injured, for the matter of that- keeping them alive at all costs - will be looked back on by future generations the way we look back at the way they prodded and laughed at the lunatics in Bedlam: as totally inhumane. I don't know. But I do know I am very glad indeed that I live in a time when the terminal miseries that were once unavoidable can be brought to an end with kindness and humanity. And I just hope they get the law in this country adjusted before it's my turn to go.

© Professor Katherine Whitehorn, 2009

Part of:

This event was on Wed, 09 Dec 2009

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login