Affairs of the Heart: An Exploration of the Symbolism of the Heart in Art

Share

- Details

- Transcript

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

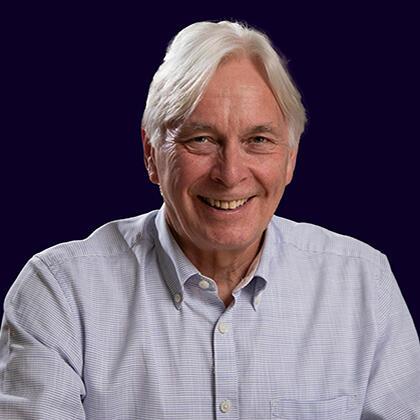

A celebration of the heart for St Valentine’s Day. How is it that a simple pump has become a symbol of the highest human emotions of love, truth, conscience and moral courage? How have artists represented this over the centuries? And how effective have those representations been? This lecture will be an interdisciplinary presentation by Professor Martin Elliott and Dr Valerie Shrimplin (art historian and registrar of Gresham College).

Download Transcript

14 February 2017

Affairs of the Heart:

An Exploration of the Symbolism of the Heart in Art

Professor Martin Elliott and Dr Valerie Shrimplin

Welcome to the Museum of London for this St Valentine’s Day lecture. Valentine’s Day is a day for romance, flowers, chocolate and, of course, hearts. My connection with the heart is both obvious and by now well known; it has been the overall theme of my series of lectures. Even the Gresham grasshopper has a heart. Actually, it has many hearts…segmentally along its aorta.

Once again, I am delighted to be speaking in front of what is always a special Gresham audience. I love the Gresham audience. My heart has been pierced!

That single image of a pulsating heart is a symbol; something used to signify ideas and qualities. The images acquire symbolic meanings that are different from their literal sense. A picture is worth a thousand words, and you instantly grasp the meanings of these symbols, without the use of words. How these symbols have evolved and came to have such instant and effective meaning is what we are to discuss this evening.

I am delighted and honoured to share the delivery of this talk with Dr Valerie Shrimplin, who many of you will know is the Registrar of Gresham College. She is also (fortunately for all of us, and especially me) a card-carrying art historian with a particular interest in the symbolism of the heart in art. Unlike some others, I seek out the experts and how lovely it is to have one in the office, so to speak.

My expertise has been in the form and function of the human heart, both in its normal and abnormal state. I find it a most amazing organ, and remain staggered by its efficiency, effectiveness and longevity. The heart though has been special to we humans not just because of the form and function which so fascinate me, but for thousands of years it has had figurative importance as well. It has been seen as the seat of the soul, the home of emotion, the core of strength and elemental to the concept of humanity itself. These philosophic concepts have persisted for millennia, and are reflected in the images that Valerie will discuss later.

Between us we want to consider how this muscular pump acquired the shape and metaphysical properties we have come to associate with St Valentine’s day. St Valentine’s day has a rather obscure history, but probably has its roots in the Roma festival of Lupercalia, which was a fertility festival traditionally celebrated on the 15th February.

Lupercalia is named for the Roman God Lupercus, who is the Roman equivalent of the Greek God, Pan. He was God of the shepherds, and his priests were nude, except for a goatskin. Around the ides of February, a goat and a sheep were sacrificed and salt-meal cakes (mola salsa), prepared by the vestal virgins, were burnt.

Plutarch, in “Life of Caesar”, described Lupercalia thus; “At this time, many of the noble youths and of the magistrates run up and down through the city naked, for sport and laughter striking those they meet with shaggy thongs. And many women of rank also purposely get in their way, and like children at school present their hands to be struck, believing that the pregnant will thus be helped in delivery and the barren to pregnancy”.

Even today, you can find Valentine’s Day cards which recall this festival, and artists have had great fun with it over the years; for example, the 1907 sculpture by Conrad Dressler from the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool.

The early church (unlike its later incarnations) appears to have had a problem with all this whipping and sex, and in 496 AD Pope Galasius 1 recast the pagan festival of Lupercalia as a Christian festival, moving it to the 14th February and renaming it St Valentine’s Day. The story goes that it was moved to the 14th because all three Saints called Valentine are said to have been martyred on the 14th of February. The next St Valentine had better be careful in the winter. In 1969, the Catholic church removed St Valentine’s day from the liturgical calendar.

Others have argued that the origin of St Valentine’s Day comes from the Norman festival of Galatin. Especially since a Galatin is ‘a lover of women’. And a corruption of Galatin to Valentine is maybe not a stretch too far.

I am going to hand over to Valerie shortly, but before I do I want to show you an image that she will discuss in more detail a little later. This is 3500-year-old Olmec object showing a man holding a heart. I could not help but be drawn to several fascinating features which reveal how little is new in our world. Note the hair piece, the small hands, the orange skin and of course the tendency to wear the heart on his sleeve. Remind you of anyone?

Now may I ask you please to welcome Dr Valerie Shrimplin.

I am most grateful to Professor Martin Elliott to invite me to contribute to his lecture today on the symbolism of the heart in art. Epitomised by the immensely familiar slogan ‘I ♥ whatever’ – which is known the world over, this interdisciplinary Art/Science lecture will examine the symbolism of the heart in art - relating the heart as symbol of life, courage and love – to it to its actual anatomical role as the source of life - on this, most auspicious, Valentine’s day.

Many years ago, the chance juxtaposition of a GCSE Biology Text book with an image of a heart symbol in the Valentine’s day edition of the Times that day, led me to contemplate how the curious, oddly shaped, asymmetric and bloody heart became transformed into the symbol that is familiar worldwide today (an amazing muscle used as a pump) came to be represented as a beautiful, pristine and symmetrical form – a symbol of a wide range of emotions varying from pain, love and devotion, to moral courage and physical fortitude. More specifically…How did depictions or diagrams of a real heart, become transformed into the universally known symbol?

Background

The symbolic depiction of the heart in art has a long tradition, stretching back to the ancient Egyptians, and classical Greek notions of erotas (romantic love) and agape (spiritual love). The symbolic role of the heart can be traced through history via the Judao-Christian religion linked to scriptural notions of religious spirituality, but also linked to medieval and Renaissance notions of chivalry and the crusades. Medical developments also played a part as the symbol developed up to our own time, where it is now used to focus mainly on the notion of love and romance. The relation of these traditions to the actual human body and the way in which the anatomically incorrect symbol derived from the physical object (to which it bears little relation) merit investigation. In art, as in literature and poetry, the heart is associated with religious and spiritual symbolism as well as the profane and sexual, or even with evil. Yet what were the origins of the visual depiction of the human heart what is the range of its symbolism? and how can we explain why the symbol, so familiar today, evolved as it did?

Amongst all the symbols that have passed into common everyday usage, the symbol of the heart must surely be one of the most universally comprehended, yet it is curious that the familiar symbol actually bears little or no relation to the anatomical object which it purports to represent. No single part of the human anatomy acts as such as significant focus for physical and emotional well-being – or pain. No part of the human body has been more associated with the concept of beauty and its corollary, love. Heart symbolism, with the image as representative of a wide range of emotions from joy and pain, love and devotion to moral courage and physical strength, is securely embedded in western culture. As well as being used to indicate a wide range of emotions, the heart is associated with spiritual symbolism, in addition to human love. The heart may also (conversely), be associated with evil – as in ‘evil and black-hearted’ etc. – as well as with some types of physical, mental or spiritual strength. The aim here is to trace the origin of the visual depiction of the human heart, and to determine the range of its symbolism – up to the present day. The relation between the anatomical object and the universally accepted symbol is by no means easy to explain. It is also somewhat dependent upon artistic interpretation, the capabilities of individuals accurately to depict physical objects, the extent and role of the study of anatomy by artists, and the whole concept of a symbol of a lifelike or real object.

Symbolism in Art

Before considering the origins of the visual depiction of the heart, it is worth remembering that use can be made of a symbol, whether or not it is totally visually correct or accurate. In fact, physical objects appear frequently to be stylised before taking on a symbolic role. Artists may be attempting to achieve either a symbolic or a naturalistic effect. While the study of anatomy was investigated in ancient Greece, it was not seriously undertaken in the west before the Renaissance. Artists clearly developed a knowledge of external physical characteristics, such as faces and facial expressions, limbs, arms, hair, eyes etc. But the heart is the one object that is so extensively depicted without normally being visible - the only interior organ to be commonly depicted, even now.

It would be very uncommon for an artist (or anyone then as now) to see a human heart - therefore where would the idea come from? In the Western European tradition, the abstracted symbolic shape could be a deliberate attempt to show that it was not a real heart, in order to avoid dangerous accusations of illegal dissection for artistic purposes. Anatomical accuracy could have brought serious repercussions and recriminations. On the other hand, familiarity with animal hearts (at the butchers) would have been a common occurrence. The only other internal feature/aspect of the human body habitually portrayed in art is of course the skeleton (and skull). This was used, for obvious reasons, as the symbol of death, while the skull itself was often used as a memento mori to symbolise the transitory nature of life on earth. While skulls and skeletons could well be familiar to the general populace - owing to burial customs as well as violent times and methods of public execution, the opportunities to see an actual human heart would have been far less frequent. As nowadays, and with the exception of members of the medical profession, encounters with animal hearts would be far more common.

Egypt

It is strange that the very earliest examples of the depiction of the human heart sometimes appear to be the more anatomically correct, like the Man Holding Heart (Olmec Civilisation, Mexico c 1500 BC) and examples from ancient Egypt. This can be accounted for by the familiarity with the actual organ, due to sacrificial or burial customs. Attention paid to the human heart and the earliest traditions of heart symbolism originated in ancient Egypt where, as the most vital organ of the body, the heart was associated with the seat of the soul and the intellect. While not practising anatomical dissection for artistic purposes, the Egyptians customarily left the heart as the only part of the viscera retained in mummified bodies, so its actual physical appearance could have been familiar to ‘artist-priests.’ It received special treatment during the embalming process and was the only organ to be mummified. Its appearance as symbol of life in depictions of the weighing of soul in the Egyptian tombs and in the Book of the Dead was therefore more closely derived from the physical object. The decorators of the pharaohs’ tombs would have had access to the viewing of actual human hearts and this is the area where some of the earliest known representations of human hearts occur. While associated in modern times with the concepts of love and hate, these early approaches to heart symbolism associated

In the Egyptian Hall of Judgment, the heart of the departed was weighed in the presence of the god Osiris, as it was placed in the scales of justice and assessed against the feather of Ma’at, goddess of truth and justice. So some of the earliest images of the heart are to be found in depictions of the heart of the deceased being weighed, to determine whether the heart has become heavy through misdeeds. Many visual depictions of the process still remain, such as the examples to be found in depictions of the heart of the deceased being weighed in judgment (as in the Book of the Dead, British Museum). The representation of the heart here seems to be more naturalistic and accurate (The Weighing of the Heart from the Book of the Dead of Ani, c 1300 BC). Anubis weighs Ani's heart against the feather of Maat, observed by other gods and goddesses who sit in judgment and wait for the result. Generally thought of by the ancient Egyptians to be the seat of the intelligence, and source of knowledge, the heart was crucial to Egyptian death ceremonies. Such attributes are now more commonly associated with the brain, whilst the heart and heartbeat rather have the key role as the central organ of the circulatory system, essential for life and heartbeat. It took a long time for human beings to work this out.

The role of the heart as the location of intelligence, will and the emotions was also demonstrated by the Egyptian god Ptah who planned the creation of the universe ‘in his heart’ (‘Ptah conceives the world by the thought of his heart’) before calling it into existence. The legend of Isis and Osiris, as retold by Plutarch also shows how the heart was viewed as indispensable to the body, and used as a symbol of eternity. The priests of Egypt took extreme care to safeguard the heart of the dead so that it might accompany the body in the afterlife.

Greece and Rome

The ancient Greeks also recognized the importance of the heart in its physical role in the body, but its role in ancient Greek culture was linked with the myths of Aphrodite and Eros (Venus and Cupid), and the distinction between erotas (romantic love) and agape (spiritual love) – which seem to form the underlying basis of the two trends of secular romantic and chivalrous love – and religious or spiritual love, as we shall see. The depiction of the heart is key to both trends, as well shall see. These concepts were particularly developed by Plato (c 424 – 348 BC) as part of the major theme of platonic love, to be revived by the neoplatonists in fifteenth-century Florence.

In this quick survey, the medical work of Galen of Pergamon, a prominent Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire (130-210 AD) stands out. Aristotle (384-322 BC) had characterised the heart as the locus of the soul and source of nervous action and intelligence, with the brain as of secondary importance. Galen disagreed. His understanding of medicine and anatomy was influenced by the popular idea of the four humours (black bile, yellow bile, blood, and phlegm), as advanced by ancient Greek physicians such as Hippocrates (born c 460 BC). Roman law had prohibited dissection of human corpses (c 150 BC) so Galen first concentrated on animals, especially apes. Among Galen’s major contributions to medicine was his work on the circulatory system, identifying differences between bright arterial and dark venous blood, believing the former to originate in the heart from when it was distributed around the body. His ideas lasted until Vesalius’s work in the sixteenth century, finally being superseded in 1628 when William Harvey established that blood circulates with the heart acting as a pump.

Heart shapes appear in the depiction of the Pantocrator in the Byzantine Church of Aghia Sophia in Constantinople (11th century – with the Emperor Constantine Monomachos and Empress Zoe) but may not necessarily be intending to depict a heart.

Judaeo-Christian – religious/spiritual ideas

While heart symbolism is also significant in the Chinese, Buddhist, Hindu and even Aztec traditions, the Judaeo-Christian tradition, based on Biblical sources, accorded it great spiritual significance. The concept of the heart as the inner person is expressed, for example at 1 Samuel 16:7 (But the lord said … Look not on his countenance or on the height of his stature ... for the Lord seeth not as a man seeth: for man looketh on the outward appearance, but the Lord looketh on the heart), so the associated idea of the heart as the seat of spiritual or emotional feeling, wisdom, purity or righteousness, as well as the operations of human life, also derives from innumerable Biblical sources, for example Deuteronomy 6:5 ; Psalm 24:4 and I Kings 3:12 in the Old Testament - or Matthew 5:8 (blessed are the pure in heart) and Mark 22:37 in the New. There are over 100 references to the heart in the Psalms. The heart can also be the seat of evil (Ecclesiastes 8:11) and care of the heart was emphasised even then (Proverbs 4:23): Keep thy heart with all diligence; for out of it are the issues of life (perhaps to be taken literally as well as metaphorically).

In Christian iconography, the heart took on a symbolic role as an indication of love of God and of piety, especially when carried by a saint. A flaming heart indicated extreme religious fervour, for example as an attribute for St Augustine, while other saints also bore the heart as symbolic of their spirituality - including St Anthony of Padua, St Catherine of Siena and St Bernardino of Siena. The five wounds of Christ came to include the pierced heart rather than the pierced side. The heart gradually took on its symbolic shape, being a recognisable symbol, as when carried by a saint, when it is symbolic of love and piety. The flaming heart represents extreme religious fervour (ie it can be painful) – such as in the stigmata – of St Francis of Assisi. Later theological teaching incorporates numerous allusions to the heart, as the seat of emotions. St Augustine’s heart is pierced by an arrow (in a medieval not modern romantic tradition), to suggest spirituality, contrition and repentance (brought about by Augustine’s dissipated early life (As told in his Confessions and City of God), the idea of welcoming pain as linked to remorse and punishment also recurs in images of St Teresa of Avila, as we shall see.

The actual iconography or depiction of the heart appears somewhat elementary until the early Renaissance, when a complex flowering of the religious and allegorical subject matter was combined, and significant changes occur.

By the early fourteenth century, however, hearts start to appear in religious art works – portrayed as ‘streamlined’ versions of the physical object – and possibly based on animal hearts, human dissection being prohibited. In the Arena Chapel Padua (c 1305), God hands a heart to the figure of ‘Karitas’ (Charity) by Giotto di Bondone. A similar example of ‘Charitas’ with a heart is shown that by Andrea Pisano, on the south doors of Florence Baptistery c 1337. In a later work (in the Lower Church, S Francesco, Assisi c 1330), Giotto links religious and spiritual love with classical romantic earthly love in his Allegory of Chastity (c. 1320-25). Cupid is depicted as a youthful, blindfolded figure inscribed ‘Amor’. The hearts of his victims, somewhere between the anatomical object and the modern symbol, are, as Panofsky puts it, ‘threaded ... like scalps on the belt of an Indian.’ Here, the hearts have a degree of anatomical correctness, but also seem closer to the modern image.

Another religious early renaissance example is the relief by Donatello, The Miser's Heart, in the Basilica of St Anthony in Padua (1446-48). The scene is based on Luke 12:34 ‘Where is your treasure, there is your heart’ as the dead Miser's heart. The Miser’s chest is found to be hollow but his heart is found in a coffer on the left of the panel, with his gold as the object of his affection. Bearing more close resemblance to the modern symbol, the hearts seems to be dangling from a trachea and it is interesting that human dissection was legalised in Padua in 1429 as part of the development of medical schools (corpses of executed criminals were used). Scientific developments in the Quattrocento (15th century) led to artists like Giovanni di Paolo crossing artistic and scientific boundaries – as the heart symbol in his painting St Catherine of Siena exchanges her Heart with Christ, 1460, whilst a northern European codex in Stuttgart of similar date shows the heart symbol as we know it – transferring the wounds of Christ from His side to His heart to emphasise spiritual and sacred love.

Medieval Chivalry, Chaucer and the Crusades

Alongside the religious depictions of the heart in the medieval and early Renaissance periods, there is another strand – the secular or romantic. It is from this time that the depiction of the heart became stylised in the way we know it, based on the shape of an inverted ‘A’ for ‘Amor.’

During the era of the crusades, the symbol was particularly regarded as one of bravery and courage as much as love, it was not unusual for the hearts of men killed in battle to be sent back to their home land for burial, as indicated on many crusader memorials, such as that of Richard the Lion Heart (died 1199), whose heart was embalmed and buried at Rouen cathedral whilst his body was buried at Fontevraud Abbey in Anjou. The concept was widely followed, such as the heart shrine at the church of SS Peter and Paul, Leybourne Church. Sir Roger de Leybourne died in France c 1270 on the way back from the crusades. His heart was sent home and placed in a casket of the Heart Shrine on the north wall of the church (cf St Giles, Horsted Keynes, West Sussex where there is another example).

Developing from notions of chivalry and courtly love, emanating in particular from France and writings such as The Romance of the Rose, the heart played a significant role in the tradition of medieval courtly love. The French text “ Roman de la Poire ” (c. 1250) pictures a kneeling man handing his heart to a love interest – an early example of the heart symbol signifying love in a metaphorical context. And these ideas were further romanticised for example by the poetry of Chaucer (c1340-1400), arguably the founder of the concept of St Valentine as patron of matchmaking. His famous, but faintly sarcastic, portrait of the Prioress from The Canterbury Tales, ends with a description of her rosary which emphasises the power of love rather than Christ (although possibly interwoven).

Of small coral aboute her arme she bar

A peire of bedes … and thereon heng a broche of gold full shene

On which there was first write a crowned A

And after, Amor Vincit Omnia

(Ellesmere manuscript, early 15th century, from the Huntington Library).

Chaucer is often attributed with the invention of St Valentine’s Day with its modern love theme. His Parliament of Fowls c 1381 contains the earliest known reference to Saint Valentine’s Day as associated with romantic love – far nicer than the legend of St Valentine himself who was beheaded for performing illegal marriages. Lines 298-310 describe a fair queen, enthroned in a bower on a hill of flowers. The birds came to her to listen and hear their fates, for this was St Valentine’s Day when all birds came to make their choices. It was clearly a special, romantic day for ‘lovebirds’. Chaucer can probably not claim (be accused of?) full responsibility for the millions of cards, flowers and chocolates sold nowadays since the feast of St Valentine’s day was also derived from the Christianising of the Roman feast of Lupercalia and the writings of other late medieval romantics, such as Renée of Anjou and Chretien de Troyes in the 15th century. However, the courtly and chivalrous traditions of the late middle ages increasingly laid emphasis on the heart as a symbol of love rather than spirituality or (as in ancient times) intelligence. A remarkable suit of armour dating from this period shows the heart emblazoned on a breast plate – miraculously close to two dents caused by musket balls – and other examples of pendants and carvings in various castles also date from this time. The heart brooch from the Fishpool hoard c 1464 is an exquisite example of a romantic love token (part of largest hoard of coins ever found, 1966 – British Museum).

As a popular Renaissance emblem, the heart contributed to the development of neo-Platonic love symbolism and the importance of love cults in the Renaissance. The De Amore of Marsilio Ficino (1433-99) was the most famous treatise of its time, covering beauty, love (agape and erotas) and desire. Heart symbols also became related to the increase in Venus mythology and tales of cupid and ‘Amor’ in the Renaissance (such as Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, and innumerable paintings of Cupid, Venus and Adonis by artists like Giorgione and Perugino). A particular influence in the dissemination of such symbols was Andrea Alciato, whose first book of emblems (1531) shows the Eagle devouring Prometheus’s heart/liver. A related source could well be the treatise Documenti di Amore, composed, written and illustrated by Francesco Barberino around 1318 (with a printed version produced in 1640). This combines the, by now traditional, ‘blind cupid’ – winged and holding quiver, arrows and roses, but with a string of hearts around the horse’s neck. Similar themes appear in the sixteenth-century tapestry in the Paris Musée des Arts Decoratifs depicting Petrarch's Triumph of Love in which the heart is a symbol of Charity [love] personified. Even medical works, such as the Medical treatise by Aldebrande of Florence 1356, clearly now allude to the abstracted symbol

Of course, developments also took place in the sixteenth century in anatomical investigation at this time as well. Leonardo's anatomically correct drawings of the heart seem way ahead of their time since it was many years before this work was followed by Vesalius, William Harvey and others, who eventually determined the true anatomical function. But when does a scientific drawing become an art work?

Such interests were not confined to the Italian neo-Platonists. In Northern Europe too, several examples demonstrate the way that the abstracted heart shape heart was becoming a well-known and recognisable symbol. In a woodcut at the Wellcome Library by Meister Casper (c 1470), Venus stands on a heart, holding a sword and spear that pass through other hearts, as she is surrounded by other hearts, pierced with arrows, saws and daggers in an allegory of the power of Venus.

At about the same time (1480s), Portrait of a Young Man, by the Master of the view of St Gudula, Brussels, shows the Heart as being like an open book. Lucas Cranach the Elder, in his Four Saints revere the arms of a Sacred Heart Society (1505), shows Christ crucified on a sacred heart – and similar representations of the symbol occur in German manuscripts around 1500. An image from the French text “Petit Livre d'Amour” (c. 1500), shows a man “depositing his heart in a marguerite flower,” - the flower being the symbol of his lover.

In England, too, in the sixteenth century, links were widely made with love symbolism, such as the revival of the classical Venus myth and even the legend and cult of St Valentine. Chaucer has already been mentioned and the tradition was becoming even more securely established in the sixteenth century. Shakespeare’s Romeo sighs Did my heart love till now? Forswear it, sight, for I ne'er saw true beauty till this night and Valentine’s day is wistfully referred to by the lovelorn Ophelia in Shakespeare’s Hamlet: Tomorrow is St Valentine’s Day/All in the morning betime,/and I a maid at your window,/to be your Valentine. John Donne famously referred to the Saint’s Day in his poem to celebrate a Royal marriage in 1613.

At the same time, the heart as religious symbol becomes increasingly stylised, being used as part of both Protestant reformed symbolism (such as works of Martin Luther) to the Catholic and Counter reformation – such as Ignatius Loyola and the Sacred Heart of Jesus. It is thus from the sixteenth century, just as more was being discovered about the anatomical heart, that the heart seems to become even more stylised, as the symbol we recognise today. Martin Luther's own seal, with a heart, remains a widely recognised symbol for Lutheranism, intended as signifying his own theology. It was designed for him (commissioned by his patron John Frederick of Saxony) in 1530 and the symbolism was explained by Luther in a letter of 8 July 1530. Luther saw the image as a compendium of his faith, a black cross in a heart to remind us that faith in the crucifixion saves mankind – For one who believes from the heart will be justified (Romans 10:10). Luther further explained that the cross is black since it brings pain; the heart retains its colour because it gives life (example from the church in Cobstadt, Thüringen, Germany).

At around the same time, the Jesuits, founded by St Ignatius Loyola in 1540, also chose the heart as one of their symbols, often pierced by three nails and encircled by crown of thorns. The emblem of the Christian sacred heart was widely venerated from the 17th century and innumerable examples from the seventeenth century to present day churches are easily found. Bernini’s statue of St Teresa of Avila appears in ecstasy as her heart is pierced by the arrow of devotion (1645-52). The impulses of the flesh are consumed by the fire of the Holy Spirit as her heart, pierced by an arrow, symbolises her love of God and her suffering for humanity. During this period, the symbol was part of the whole tradition of religious iconography in terms of the depiction of saints. Devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus continues to be one of the most widely practised and well-known Roman Catholic devotions, as Christ’s physical heart comes to represent His divine love for humanity. The effect of all this on the arts was significant, as paintings, symbols and mementos, showing a sword piercing Christ’s heart, crowned with thorns and circled by flames proliferated. Images show how the organ, recognised in the scriptures as crucial to life, gradually became abstracted even at this stage. An asymmetrical, distorted, even messy, object is used to symbolise all these higher feelings and aspirations. It is intentionally not depicted in a naturalistic way. Yet one very unusual example from Jesuit missionaries in Mexico, The Sacred Heart of Jesus with two Jesuit Saints (Ignatius of Loyola and Aloysius Gonzaga) by Jose de Paez, 1770, shows the intention to allude to scientific advances, tubes and all. Nineteenth-century versions, such as the Catholic holy card depicting the Sacred Heart of Jesus, circa 1880, continue the heart symbol in a traditional way. The approach appears to culminate in the Church of the Sacré Coeur in Montmartre (dedicated 1871), where the cult and heart symbol was immensely important (long before Paris became a fashionable destination for romantic couples on Valentine’s Day!).

The tradition of heart symbolism is also to be found in other civilisations and cultures, such as the Chinese, Indian and Aztec traditions, where human sacrifices and burial practices would allow actual views of the human heart to occur - but space does not allow contemplation of these here.

The romantics tradition also continued in nineteenth and twentieth century paintings, where an impetus was given to heart symbolism by nineteenth-century romantic imagery, such as the Romantic Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood, and Victorian notions of the heart in the earliest Valentine cards, popularised heart-shaped lockets and so on. A quick survey of twentieth-century examples reveals that the ‘Heart in Art’ continued throughout, with works by leading artists like Munch, Miro, Magritte, Kahlo, Hockney and Lichtenstein. Peter Blake takes this into the twenty-first century and, not unexpectedly perhaps, Damien Hirst’s art works based on anatomical dissections also feature the heart (The Immaculate Heart – Lost, 2008).

The use of the symbol in advertising is now of course incredibly widespread – a controversial example being the Benetton advert of 1996. Intended to signify that inside we are all the same, the advert using pigs’ hearts was banned. By contrast, modern Valentine’s cards and gifts are all over the place at this time of year. An estimated £11.9bn was spent on Valentine’s day in the UK last year and about $19.7 billion is spent each year in the USA. Some 190 million cards with heart symbols on them are produced - but of course most of this not to be counted as ‘art’.

From public art to emoticons, the heart symbol is immediately recognised – and is amazingly used in the medical context such as CPR and defibrillator training! It still reflects love, courage, joy and devotion (or by contrast the sorrow of a broken heart). Everybody knows that the heart is not really shaped like an inverted A, but the universally recognised symbol, by abstracting a vital but curious, asymmetrical, distorted and even messy part of the body continues to symbolise the wide range of emotional and intellectual ideas relating to the centre and essence of being/human existence.

Martin Elliott

Surgeons have a reputation for being concrete thinkers. Craftsmen and not artists. Barbers and not scientists. In many cases that may be deserved, but by far the majority of the people with whom I have worked throughout my career have recognised the beauty of the heart and its inherent artistic merit. There is no doubt that the wonderful drawings of Leonardo lie at the (wait for it) heart of that recognition. He understood the relationship between form and function much better than his predecessors, and cemented a relationship between internal anatomy and art. His drawings are beautiful, detailed and accurate. They have formed the basis of anatomic understanding for the last 500 years, and continue to inspire anatomists, surgeons and artists; and especially those with talents in both domains. Professor Frank Wells from Papworth Hospital is such a person, and he has described in his book ‘The Heart of Leonardo” how important those beautiful drawings have been to modern repair of the mitral valve.

This graphic, mixing visual and verbal concepts, was created by my colleague Laszlo Kiraly an excellent surgeon and artist from Budapest, now based in Abu Dhabi. The symbolic shape of the heart is not the real shape, but accommodates more ideas. Laszlo overlays this image by lines highlighting the inherent spirals and curvatures of the heart, which happen in multiple planes. Spiral arrangements are integral to the relationship between form and function in the heart, as they are in many other aspects of our world, for example cloud systems, the nautilus shell and the arrangement of muscle fibres at the apex of the heart.

Helical arrangements of muscle fibres were also demonstrated in beautiful 19th century drawings by J Bell Pettigrew, and helical contractile elements are confirmed using MRI.

500 years ago, Leonardo did experiments involving placing grass seeds in flowing water to demonstrate the patterns of flow around obstacles. This early work on turbulence also predicted imagery which we use daily to help us both understand the workings of the heart and to decide what to do in situations of abnormal flow patterns. We can use echocardiography, in which turbulence is visualised using the Doppler principle, interpreted on the screen as colour.

MRI has added both precision and beauty to this work, also now visible in real time, but able to be subjected to detailed post hoc analysis.

Philip Kilner from the Royal Brompton Hospital sent me this image of blood flow in the right atrium. A beautiful spiral, coloured by the computer reconstruction. Philip Kilner is another artist-physician. As well as being one of the world’s leading cardiac MRI specialists, he is also a recognised sculptor and artist. He perfectly exemplifies the bridge between science and art, having made it to the cover of nature in the first branch and being regularly exhibited in the second.

Philip created a fascinating sculpture which used to be on display at the Royal Brompton Hospital. Similar in shape to the atria of the heart, continuous flow of water entering at the top of the sculpture becomes intermittent or pulsatile flow as the water leaves the sculpture. I love this piece of work and it is a great shame that it is no longer on show.

Images of the heart created by modern medical technology have a beauty of their own. You just need to add a picture frame, and maybe a signature and you have the makings of an exhibition! Science, art and symbolism merge in the context of the heart. Form and function fuse to great effect. It is no wonder then that the heart has for so many centuries been regarded as the seat of the soul, and the stimulus for so much romantic symbolism….despite what some graffiti artists consider some of the excesses of St Valentine’s Day.

Thank you, and we hope you enjoy the rest of the evening!

© Professor Martin Elliott, 2017

© Dr Valerie Shrimplin, 2017

Further Reading

Wells, Francis The Heart of Leonardo 2013 Springer ISBN 978-1-4471-4530-1Young, Louisa The Book of the Heart 2002 Flamingo, London ISBN 0 00 710911 3Vinken, Perre The Shape of the Heart 1992 (reprinted 2002) DTP Fokker Druckwerk, Amsterdam ISBN 0-444-82987-3Boyadjian, N. The Heart 1985 Esco Books, AntwerpLozadi, Karoly & Kiraly, Laszlo Szivparafrazisok 2013 Medicina, Budapest

Special Thanks to

Professor Laszlo Kiraly, Abu Dhabi

Professor Philip Kilner, The Royal Brompton Hospital

Part of:

This event was on Tue, 14 Feb 2017

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login