Cultural Revolution: Palaces of the Early Stuart Kings

Share

- Details

- Text

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

King James I was a gust of fresh air after the later years of Queen Elizabeth. Unlike his predecessor he was a family man, with dynastic ambitions and big ideas about architecture. But neither he nor his son, Charles I, became the great patrons of building that they would have liked.

The lecture explores how their unrealised ambitions contributed to the downfall of the monarchy.

Download Text

8 October 2014

Cultural Revolution:

Palaces of the Early Stuart Kings

Professor Simon Thurley

King James I was an extraordinarily active and mobile monarch moving from house to house far more frequently than any since the middle ages. Over his reign James spent the largest number of nights at Whitehall. This shows that even for the monarch who hated London more than any other (apart from perhaps William III) Whitehall was essential for the business of running the country. He was most frequently there during the seven parliamentary sessions of the reign generally staying for bursts of a week at a time. He also spent Christmas and twelfth night at Whitehall almost every year. These were still the most important court occasions of the year when the king publicly took communion in the chapel and the court was bursting at the seams.

Theobalds was, by quite some way, his most visited country residence but his stays were very short, often only a night and on average over the reign only three days each. For such a big house this is surprising, these short visits were generally brief hunting trips usually with only a small retinue in tow. Yet the house was used on occasion for big events and when it was first purchased these may have been what was in mind as his principal extensions were in the service quarters.

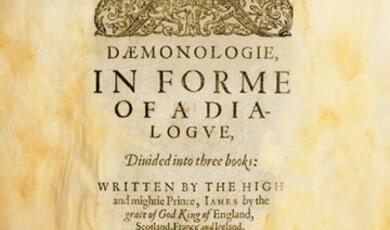

James probably spent as many actual nights at Royston as he did at Theobalds, although he visited the house about half the number of times. Royston was possibly the most extraordinary royal building of the seventeenth century. Extraordinary in its chaotic and inchoate architectural form; a mere conglomeration of private houses and inns in a small town centre with a larger block for the king’s use. In the teens of his reign James often stayed there for a fortnight or more, certainly hunting, but spending as much time reading and writing. Here and at Newmarket he wrote seven or eight books.

Greenwich was visited for a similar number of days as Royston and was visited in May and June as an early summer hunting trip before the court went on progress. Hampton Court was less favoured than Greenwich but, as I will explain, visited every year after progress time. After 1618 his stays were brief, often only one or two days for hunting. Then comes Newmarket, far less popular than the others but most years there was at least one spring and one autumn visit.

If we look at expenditure on these buildings we see that the big money does not follow the king’s scatty and capricious itinerary. Whitehall, always cost the most. Its sheer size and propensity to decay made it the most expensive palace to maintain right up to its destruction. Below that, in order of magnitude comes expenditure on Somerset House and Greenwich, and below them the houses of the Princes of Wales Richmond and St. James’s. I am not going to talk much about Richmond or St. James’s as actually very little was built new. Much of the expenditure was internal refurbishment. The costs of new build, conversion and maintenance at Royston and Newmarket were relatively insignificant. Of course the most simple explanation for this expenditure was that James was the first monarch to have a family since Henry VIII.

In 1603, research was commissioned into the archives to determine how to constitute and configure the household of the queen and her children. Anne of Denmark was not just a consort, she was of royal blood, and thus was the first queen of England, since Katharine of Aragon, who was a princess in her own right. Part of the research was to determine the Queen’s jointure - the lands and properties which she would be granted for life and which would provide income and lodging for her and her household.

Somerset House was given to the queen as her principal London residence. After its refurbishment in 1609-12, it became her principal residence. Anne was only granted a significant country house in 1611 when Oatlands near Weybridge in Surrey was added to her jointure. The Queen immediately embarked on a series of improvements there making the house very much her own. The addition of Greenwich to her portfolio in 1614 was largely because James had little interest in it.

I want to start with Oatlands Anne’s country house. What has become clear is that Oatlands was one of the Stuart Court’s principal residences used almost every summer for the queen’s hunting trips and particularly by Henrietta Maria while Charles I was on progress or away on business. Despite the fact that Oatlands was favoured so highly by the Stuarts it was relatively little altered from its Tudor state. After 1611 (the year in which Anne formally took possession of the mansion) work was done to modernise the king’s library, the queen’s withdrawing room, bedchamber and the chapel. In 1616 the queen had a new privy kitchen built. More significantly, in the period 1616-18, the gardens to the south of the house were much improved. The queen ordered, from her own privy purse (i.e. private income), a vineyard with an adjacent ‘longe privy walke’, and a walled kitchen garden. The Vineyard had a great gate of stone, designed by Inigo Jones.

It should not be doubted that Anne of Denmark regarded Oatlands as her principal country house and it is very clear that much of each summer was spent there in recreation, especially hunting. In 1617 while James was in Scotland Anne held court at Oatlands commissioning Paul van Somer to paint her portrait mounted, in hunting dress, with her house in the background.

At Queen Anne’s death a series of inventories were prepared, a source not previously analysed. Not a single one of the tapestries that filled the house in Henry VIII’s time remained, gone also were the great Tudor state beds and canopies; in fact Anne’s house was entirely furnished with modern furniture and silk wall hangings in a rainbow of colours. The walls were adorned with easel paintings; for instance in the gallery by the vineyard was her own portrait by Van Somer and portraits of her brother, and her family in Denmark. The inventory allows us to make sense of the repair accounts which chronicle the re-panelling and redecoration of the queen’s rooms. Anne completely modernised the queen’s royal lodgings creating a suite of up-to-the-minute rooms in her main country residence. The contrast with the neighbouring house of Hampton Court could not be more marked. There James I and Charles I kept the Tudor décor largely intact and even slept in beds that had been used by Henry VIII.

Greenwich was the queen’s other country house. This palace, much regarded by the Tudors took on a very particular function under James I. James brought a new formality and organisation to diplomatic activity. He needed to. The stability of the joint kingdom and the future of the Stuart Dynasty rested on the marriage prospects of his three children. That future would have to be secured through diplomacy. So James created for the first time the post of Master of Ceremonies following the practice of most continental monarchies. This was only one consideration. James also needed recalibrate his royal residences giving each a specific and distinct role in diplomatic protocol.

Of these Whitehall was the most important. It was here that James I had built his great presence chamber a room closely modelled on great Tudor state rooms but cloaked in the Italianate style of Inigo Jones. It has long been accepted that the Banqueting House particularly, and Whitehall itself, was the primary focus of diplomatic activity. And it was here that ambassadors had their first formal audience with the king.

Hampton Court had a crucial role to play in ambassadorial etiquette too. It was there that the early Stuart kings’ summer progress normally ended in late September or early October. During the summer months, with the court on progress, most diplomatic activity was in abeyance, but the king’s arrival at Hampton Court signalled the start of business again for the autumn and winter months. This time was therefore always characterised by a series of ambassadorial audiences.

But Greenwich’s role was reserved for the welcome ceremonies. During James’s reign a formalised sequence of three welcomes was devised. The first would be at Gravesend where the master of ceremonies, would present a welcome to the visiting diplomat. If it was an extraordinary ambassador the second Welcome would take place at Greenwich before the ambassador transferred to the King’s barge. For resident ambassadors this speech was made on Tower wharf before they transferred to a cavalcade of carriages surrounded by courtiers and city aldermen. After this either type of ambassador would have their first reception at Whitehall.

Greenwich’s position on the river to the east of London made it the natural stopping-off point for visitors into London. Its first important Jacobean usage was for the reception of King Christian IV of Denmark in 1606. On this unique occasion James and Prince Henry were waiting in the royal barge at Gravesend for the King. They rowed together to Greenwich where Christian was reunited with his sister. In fact it may have been this reception early in the reign that set Greenwich as the place for high status welcomes. So Greenwich had a special diplomatic function in the early Stuart period.

Henry VIII had made Baynard’s Castle, a fifteenth century riverside house in the city, the London seat of his queens. James chose the much more modern and convenient Somerset House for his. But the house that Anne found was hardly suitable for the consort of the king of England. The unfinished house was far from what she had enjoyed in Scotland where she had embellished Dunfirmline Abbey at significant expense and with considerable taste as her country seat.

Reconstruction works were to start in 1609 and continued for nearly five years. Ultimately the cost of completing and furnishing Somerset House was well over £45,000 making it the single most important and expensive royal architectural work of the early Stuart period. In comparison the cost of the new palace at Newmarket was £4,600, alterations at Theobalds £8,000 and the Banqueting House £15,000. We should not for a moment underestimate the importance of the queen’s work. Neither James I or Charles I built for themselves on this scale. The queen’s lodgings at Somerset house are the only specially commissioned and coherently designed suite of royal lodgings of the early Stuart period. And therefore the first major reconstruction of a royal palace since the death of Henry VIII.

Not surprisingly Anne decided to abandon the rooms with a frontage to the Strand which seem to have been used by Elizabeth I and in 1609 work started in earnest with the demolition of the privy gallery and the rooms adjacent to it and their immediate reconstruction with a three story tower containing closets or cabinets at its south end. At its north end was another new gallery two stories high running east terminating in a stack of cabinets including a library. The principal lodgings were substantially remodelled, but remained, largely, in their former locations.[i] To facilitate easy communication between the old lodgings and the new gallery a passage was constructed between one of the Tudor towers and the end of the gallery. Built up on arches, pilasters and columns it linked the privy chamber and the privy gallery circumventing the withdrawing room.

On the west side of the privy gallery overlooking the back court or square court were three new rooms. Two with bay windows and the central one with a large chimney breast. These were her great and little bedchambers separated by two closets, her coffer chamber and her diet chamber, essentially a breakfast room. The council chamber, bedchamber, presence and privy chambers which originally had their windows looking out onto the back court had them filled in, and new windows were made looking out south onto the gardens and, in the case of the council chamber onto the outer court.

The work was completed by Shrove Tuesday 1617 when the queen entertained James to a great opening of her new house. The king, in her honour declared that its nickname ‘Denmark House’ should henceforth become its official title.

There are a number of interesting and important points about this plan but for me the most striking thing is the careful and symmetrical arrangement of the bedchambers on the east side of the inner court. The creation of two bedchambers designated as great and little demonstrates that Anne intended to use the great bedchamber as a reception room and her little bedchamber as the room in which she slept. This was a significant innovation for a queen or indeed even a king of England.

Since Henry VIII’s divorce of Katharine of Aragon queens of England had been commoners. While these non-royal queens received ambassadors and others in their apartments there is no evidence that they used their bedchambers for formal state occasions. Anne of Denmark was in a different league to Henry’s later queens. The daughter of the king of a major European power, Anne had a clear sense of her royalty. She went to great lengths in Scotland to forge an independent royal image and power, a determination that gave James considerable political difficulties. In England Anne was no less regal. The French ambassador wrote ‘The character of this princess is the reverse of her husband’s; she was naturally bold and enterprising; she loved pomp and grandeur’. It was for this reason that Anne built herself a second, public bedroom at Somerset House just as a monarch would have done.

One incident at least suggests that the queen’s bedchamber was used as a setting for formal ceremonies of state. According to the archbishop of Canterbury, George Abbot, the impromptu knighting of George Villiers was undertaken by James in the queen’s great bedchamber at Somerset House. Clearly if James and Villiers and the archbishop were all in the queen’s bedchamber, no doubt with other company, it was a venue for public court occasions. In addition I would suggest that her requirement for a lesser or inner bedchamber was strengthened by James’s notoriously free and easy access to his own. Unlike her husband, her womanhood, Danish royal dignity and pomp required a clear separation of public access and the private world of a queen and her ladies.

I now want to move on to the French princess who became Charles I’s Queen – Henrietta Maria. Denmark House became her official residence on her marriage in 1625 and it remained her principal centre of activity until her departure from London in 1642. I want to suggest that in those years Denmark House came to symbolise, to the opponents of Charles I regime, everything that was wrong with his rule. To do that I’m now going to look – in some detail into two aspects of Henrietta Maria’s occupation of the House. The first is the nature or etiquette performed in her household and the second is her religion.

So let’s start with her domestic etiquette. Henrietta Maria came to England with an enormous trousseau and at the heart of this great baggage train was a complete set of French royal bedchamber furnishings of red velvet with gold and silver trimmings. The bed itself was magnificently hung sitting on a red covered dais and crowned with four great plumes of white ostrich feather. Three chairs, and six coffers of matching velvet and three large Turkish carpets were also provided as was ‘Une grande Toilette de velours en broderie d’or et dargent’. This bedroom suite was similar to that which her mother had in her great bedchamber at the Louvre sited behind a great silvered rail. In the French court the bedchamber occupied a central position in the ceremonial life of the monarch. Thus the bed and its furniture had a vitally important role and symbolic value. The early Stuart bedchamber, in contrast, was a private room, for the monarch’s closest intimates and the furniture, though rich and valuable, had no public function.

For Henrietta Maria, therefore, her bedchamber and its furnishings were of the utmost importance in establishing her status; while for the English the bedroom was simply a rich and comfortable private room. Two separate French observers describe the Queen’s eventual arrival at Denmark House where she was presented with the apartments of Anna of Denmark in which she expected to see a ceremonial bed reserved for her use. But ‘she found as her ceremonial bed (lit de parade) one from the reign of Queen Elizabeth, which was so ancient that not even the oldest people could remember ever having seen one in that style in their lives. Perhaps Charles and his advisors believed that Elizabeth’s rich bed would be an honour for the new Queen. They were badly mistaken or misled.

There is no doubt that Henrietta would have liked to remodel Anna’s great bedchamber along French lines immediately. However the King’s appalling financial situation coupled with the painful dispute over the size and composition of Henrietta’s household meant that little or nothing was done in the bedchamber or in any of her other apartments at Denmark House. The Queen’s bedchamber was only finally remodelled in 1632, probably in response to Charles’s plans to go to Scotland.

Plans had been long in the making for Charles to make a journey north to be crowned in Edinburgh, and in 1632 it was finally clear that Charles’s Scotch coronation would be in the Summer of 1633. Henrietta Maria was to remain in London and while not granted any formal powers of regency was at least nominally in charge and responsible for state ceremonial during the King’s absence. She was also to hold a formal weekly audience with the Privy Council. Denmark House was therefore to take the role that Whitehall would have had for Charles and the Queen resolved to redecorate her bedroom so to make it appropriate for a Queen of England who was also a princess of France. Inigo Jones designed a new white marble chimney piece for the room that was installed in April 1632. The following month a 10ft square platform 6” high was built and a remarkable green and white satin bed delivered. The ‘large rich French Bed of sattine richly embroydered’ was accompanied by ‘A Rayle and Ballaster to incompasse round ye bedd silvered and varnished over’. The ensemble also included a pallet bed for her chief lady to sleep on and, for her little bedchamber a lit de ange – an angel bed.

So did Henrietta Maria use her great bedchamber at Denmark House in the French manner? I think she certainly did. Marie de Medici, the Queen’s mother, was exiled from France in 1631 and thereafter became the chief troublemaker of Europe. She spent time in the Spanish Netherlands and Holland before arriving in London in October 1638. On her arrival St. James’s Palace was set up for her use and there is a fairly comprehensive description of Marie’s use of it including a series of prints; one showing her bedchamber with the Queen’s levee in progress, a French bed, rail and all. We know that these rather crude prints actually represent St. James’s Palace as they show the terracotta roundels we know to have been over the chimneypiece. There is a little doubt that what we see here at St. James’s was also happening down the road at Denmark House.

So for many observers the Queen of England introduced into her household a

I’m now going to move on to my second aspect of Denmark House. The Queen’s religion and her chapel.

The marriage of Charles and Henrietta Maria was first about international politics and diplomacy, not religion. However for it to take place, and for his god-daughter to rule over a nation of heretics, Pope Urban VIII had to grant a papal dispensation and for this reason his requirements were built into the marriage treaty of 1624 guaranteeing not only religious rights for the Queen but in a secret appendix wider toleration for Catholics. Most importantly Henrietta Maria was now seen by Urban VIII and the French royal family as the agent of the salvation of Britain. These images remained strong in her mind’s eye throughout her life and were perhaps encapsulated in The finding of Moses a paining she commissioned from Orazio Gentileschi and hung at the Queen’s House Greenwich. Moses, of course, as an adult, was the prophet who was to lead the people of Israel out of captivity to the Promised Land, the very thing that Henrietta Maria was sworn to effect.

However, her early attempts at demonstrating her piety in public were ill judged and contributed to the expulsion of her French Household and her Oratorian priests in 1626. They were to be replaced in 1630, with the agreement of all concerned, by twelve Capuchin Friars. Capuchins were the shock troops of the Counter Reformation, proselytisers and preachers the very best missionaries at the disposal of the Pope.

Initially the Queen’s friars established themselves in a converted tennis court hung with tapestry and lit with silver chandeliers. But two years later in 1632, in a ceremony watched by hundreds the Queen laid the foundation stone of a new chapel and Friary.

The chapel was designed by the architect Inigo Jones and was an entirely separate structure not integrated into the Palace or the State Apartments, but free standing and entered by a separate courtyard off the street. The Queen had her own private Oratory in her State Apartments. The new Friary was more akin to the houses of observant friars that Henry VII and VIII had immediately adjacent to their palaces before the reformation. Yet the chapel was clearly in plan and decoration, Catholic, with transepts, side chapels, a reredos and convential rooms behind for the Capuchins.

The Queen’s Capuchins dedicated their chapel to the Virgin – indeed they obtained permission from the Pope for it to be the location of an Arch-Confraternity of the Holy Rosary – a lay fraternity sworn to devotion to Our Lady and to bringing souls to God. This was no ordinary chapel; it was a spring-board for Roman Catholicism in England. And it was very successful – during the 1630s not only did it succeed in drawing existing Catholics it stimulated a number of high profile conversions at court. But perhaps most importantly it drew in the King: relations with the Vatican were restored and in December 1634 a papal envoy arrived at Denmark House and permanent papal agents were accredited to the Queen’s court. They may have been received in the Queen’s great bedchamber. And without doubt within the Queens State Apartments. King Charles I himself became the first English monarch for 100 years to receive a papal envoy. The King was able to use the Queens palace for an event that was without question unacceptable to the majority of Englishmen and outside the possibilities of etiquette at his own Palace of Whitehall.

Now at this point I should emphasise that Henrietta Maria is no longer seen as an uncompromising catholic bigot. In many senses she was a moderate – a conciliator – but none of this counted with observers from the Strand who saw Capuchin Friars processing round the courtyards of Denmark House bearing banners, crucifixes and statues of the virgin.

Denmark House was the single most powerful symbol of what they disliked. It is difficult to quantify the depth of feeling against the Queen and the degree to which Denmark House symbolised the elements of royal rule that they disliked. To say anything against Herrietta Maria was high treason and very risky Dr Alexander Leighton, in exchange for calling the Queen a daughter of Heth (an idolatress), was defrocked, fined £10,000, pilloried for two hours, had an ear cut off, his nose slit, his cheek branded, was flogged twice and imprisoned for life.

But safe from the censorship of London in Amsterdam this print was produced in 1642. The section I’m showing was entitled Processio Romana or King without his Parliament. At the centre is Henrietta Maria and she is at the heart of a Capuchin procession just the same as those that graced the courtyards of Denmark House. Under their habits the friars are dressed in armour and have halbards, swords, guns and pikes – the satirists message is clear, goings-on at Denmark House were a back door for a popish revolution.

The problem undoubtedly was that Henrietta Maria had no idea of the impact that her cultural and religious preferences had on the population at large, and particularly on the citizens of London. Her enormous material expenditure made her into a symbol of wanton extravagance, her masques on icon of licentiousness, her Frenchness and Catholocism a symbol of popery.

So now let’s look at the events of 1640-42 in the light of what I have just said. Disorder, rioting and violent behaviour were hallmarks of life in early modern London. But in the whole of the early seventeenth century the few years around 1640 stand out as an unprecedented period of disorder and lawlessness. Fed by plague, trade depression, political crisis and religious radicalism it can be said that London between 1640 and 1642 was nearly out of control. Thousands of citizens took to the streets to demonstrate, or more seriously, take the law into their own hands. Between March and July 1641 there were 55 days and 10 nights of disturbance and by the end of the year. Significant numbers of the trained bands upon, whom the Crown relied to keep the peace, simply didn’t respond to royal orders. When Charles I left London, effectively for good on January 10 1642 he had lost control of the capital. Amidst all this Denmark House was said to be “sheltering the Pope and the Devil”. In 1640 angry apprentices and others pelted worshippers there with stones and other missile - when one of them was caught he told the authorities that they wanted to pull down Denmark House because it was a symbol of popery.

Throughout 1641 hostile crowds surrounded Denmark House and the Embassy chapels of the French, Spanish and Portuguese. That winter the Irish rebellion and tales of the massacre of English Protestants deepened the fears of Londoners. In January several ‘rude boys and other lewed persons’ succeeded in breaking into the Queen’s chapel at Denmark House with stones causing quite a lot of damage and the following month a hungry crowd gathered outside the house in anticipation of the arrest of the Queen’s Capuchin friars.

It has to be said that these events seriously frightened the Queen who several times feared for her life. We know that when she and the King left London in January 1642 they moved to Windsor where they thought they would be safe from such attacks.

Denmark House was then in limbo for a year. The Queen was gone but the house was manned by her household and everyday the Capuchins continued their ministry and the Catholics flocked to the chapel. Then in March 1643 the patience of one MP snapped. Sir John Clotworthy, an Irish MP and religious fanatic, broke ranks and forced entry into Denmark House with a troop of soldiers.

Two French aristocratic members of the Queen’s household tried to stop them claiming that the chapel and friary were protected under the terms of the Queen’s marriage treaty. They were ignored and parliamentary troops broke down the doors of the friary and chapel. They found seven friars who were taken into custody. Clotworthy personally climbed up onto the altar and hacked to pieces Ruben’s altarpiece with a halberd then for good measure had it thrown into the Thames. He then moved onto the side chapels where he did the same to paintings of St. Francis and the Virgin, smashed a large statue of the Virgin and Child in the vestry before finding two more statues of St. Francis and the Crucifixion in the garden. He destroyed these, according to the French, by banging their heads together. The images dealt with, the gang started on the presbytery, reredos and altars all of which were demolished with hammers, and the ransacking of the vestry. A bonfire outside was fed with books, furniture, confessionals.

That summer, parliament passed an ordinance for the seizure of the King’s property including his houses. Denmark House was almost immediately broken into by a mob. The State Apartments were ransacked; furniture and paintings were stolen and smashed.

But at this point parliament realised that it was alright to condone officially sanctional iconoclasm and destruction but not wanton vandalism by the London mob. The House of Lords passed resolution securing the royal palaces and banning entry by anyone unless accompanied by two MPs and a Lord. The key of Denmark House was given to its old Lord John Clotworthy.

So does this suggest that Denmark House was a rallying point for opposition to the crown? I think it does. It was the only royal palace to be robbed and broken into, to be spontaneously attacked by a parliamentary gang. All the other royal chapels were, in due course, purged – but none in a frenzy of hate like Denmark House.

© Professor Simon Thurley, 2014

Part of:

This event was on Wed, 08 Oct 2014

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login