Legal Process as a Tool to Rewrite History - Law, Politics and History

Share

- Details

- Text

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

Trials at the ICTY concerned political violence and criminality that resulted from disintegration of a federation from which seven new successors states were formed. That process has been defined as a 'clash of state projects', where violence happened in areas claimed by two or more parties, or an aspiring state. The war crimes trials at the ICTY that resulted from overlapping territorial claims in Croatia, Bosnia and Kosovo produced a huge record of trial evidence. Problems in the very small state of Kosovo may be seen as the beginning of the violent process of disintegration, now known loosely as the Balkan wars of the 1990s. The conflict in Kosovo of 1998-9 may be seen as the end of those wars. Kosovo now seeks global recognition as an independent state but faces opposition both as to its international legal entitlements and as to how its history in the conflict should be viewed.

Conflicts in the small state of Bosnia may be seen as the heart of the 1990’s Balkan wars. Bosnia’s complex constitution and uncertain political equilibrium have left it with an insecure future. ICTY trials had several objectives, including bringing retribution and achieving deterrence but they never sought to write history and those who would seek historical truth in the trial record might be disappointed; every trial record produces at least two competing narratives, a Prosecution narrative and a Defence narrative or narratives, neither / none of which may be accurate. Yet outside the courtroom, the trial record will be used - or abused - for shaping the collective memory of the peoples and nations involved and for providing an overall narrative of the wars themselves.

The struggle for the interpretation of historical events through the trial record might be as important in long run as the determination of guilt or innocence of the individuals tried.

Kosovo and Bosnia both face a former foe – Serbia - which might like to leave a ‘historical record’ that suggests moral equivalence between Serbia and Kosovo and between Serbia and Bosnia. The ICTY’s policy of prosecuting representatives of all states /entities involved in the wars, may have contributed, some argue, to a concept of 'proportionality of criminal responsibility’ that may assist Serbia in achieving this goal. In any event, Serbia may have shown itself skilful in the use of the court system and of the court record to write or re-write narratives of the conflicts in Kosovo and Bosnia? If it has, how can Kosovo and Bosnia fight back and write their own – or at least better - narratives?

This is a part of Sir Geoffrey Nice's 2012/13 series of lectures as Gresham Professor of Law. The other lectures in this series are as follows:

International Criminal Tribunals

The end of Slobodan Milošević

The ICC and Africa

State Involvement in War Crimes Trials

Regulation at home, but not abroad

Download Text

13 February 2013

Legal Process as a Tool to Rewrite History-

Law, Politics, History

Professor Sir Geoffrey Nice

Trials at the ICTY concerned political violence and criminality that resulted from disintegration of a federation from which seven new successors states were formed. That process has been defined as a 'clash of state projects', where violence happened in areas claimed by two or more parties, or an aspiring state. The war crimes trials at the ICTY that resulted from overlapping territorial claims in Croatia, Bosnia and Kosovo produced a huge record of trial evidence.

Problems in the very small state of Kosovo may be seen as the beginning of the violent process of disintegration, now known loosely as the Balkan wars of the 1990s. The conflict in Kosovo of 1998-9 may be seen as the end of those wars. Kosovo now seeks global recognition as an independent state but faces opposition both as to its international legal entitlements and as to how its history in the conflict should be viewed.

Conflicts in the small state of Bosnia may be seen as the heart of the 1990’s Balkan wars. Bosnia’s complex constitution and uncertain political equilibrium have left it with an insecure future.

ICTY trials had several objectives, including bringing retribution and achieving deterrence but they never sought to write history and those who would seek historical truth in the trial record might be disappointed; every trial record produces at least two competing narratives, a Prosecution narrative and a Defence narrative or narratives, neither / none of which may be accurate. Yet outside the courtroom, the trial record will be used - or abused - for shaping the collective memory of the peoples and nations involved and for providing an overall narrative of the wars themselves.

The struggle for the interpretation of historical events through the trial record might be as important in long run as the determination of guilt of innocence of the individuals tried.

Kosovo and Bosnia both face a former foe – Serbia - which might like to leave a ‘historical record’ that suggests moral equivalence between Serbia and Kosovo and between Serbia and Bosnia. The ICTY’s policy of prosecuting representatives of all states / entities involved in the wars, may have contributed, some argue, to a concept of 'proportionality of criminal responsibility’ that may assist Serbia in achieving this goal. In any event, Serbia may have shown itself skilful in the use of the court system and of the court record to write or re-write narratives of the conflicts in Kosovo and Bosnia?

If it has, how can Kosovo and Bosnia fight back and write their own – or at least better - narratives?

This is the fourth of my six lectures for this academic year. All the lectures thus far have had as one focus, that the doings of the law – and the doings of lawyers and judges – should never be taken on trust. Not because they are inherently untrustworthy rather because the citizen has to be wary not to trust the law and lawyers too much. The law is, or has become, something of a religion to which international bodies representing the citizen turn in need, treating the lawyers and judges as priests and oracles able to provide not just arguments and judgments but truth.

Does the law merit this respect? Can it go further than it normally reaches by performing its basic job, especially when dealing with conflicts – international or national – on a large scale?

Hannah Arendt in her book on Eichmann and the holocaust, discussing the role of the law said: ‘[E]ven the noblest of ulterior purposes, ‘‘the making of a record of the Hitler regime which would withstand the test of history’’……….. the supposed higher aims of the Nuremberg Trials, can only detract from the law’s main business: to weigh the charges brought against the accused, to render judgement, and to mete out due punishment.’[1]

Even assuming her narrow view of the function on the law is right it is not that easy, even with the best will in the world, to confine its output or effect in the way she might have preferred. It is all too tempting for the citizen casually to allow law’s wider potential to do things beyond its proper scope.

In this lecture I consider the potential of the trial process and of trials in war crimes courts to go further than just to deal with individual criminal responsibility for actions in conflicts and to write or rewrite history for parties to the conflict

It may always be helpful to compare aspects of what is new and untested – as the war crimes trials of the last 20 years are – with aspects of what is familiar, tried and very well tested – the domestic national criminal trial. Such national system trials are immensely significant to the individual – found not guilty / found guilty / not punished / punished.

Some trials may also be highly significant for and revealing of the societies and nations in which they take place: The Dreyfus affair and the trials that were part of it certainly revealed much about French society, corruption within the army and possibly about anti – Semitism. Its record became part of French history and to the extent issues remain controversial it is a record that may be used instrumentally by those who prefer one view of history to another. Essentially, however, it remains the case of one man and is descriptive of the society in which he suffered.

Similarly with the trials of Oscar Wilde, revealing though they are of those times, they are not substantially useable as the instruments of deception about history – only of revelation.

The OZ trial showed a great deal about current standards of morality and of the seeming corruption of the legal process given the conduct of the judges. It did not however rewrite or even write history. This is the same with the trials of IRA offenders that showed a corrupt police force and the need to change legal procedures.

Exceptionally a trial can, in itself, change the history of a society. The trial of Penn and Meade in 1670 established the jury’s right to acquit a defendant in the teeth of direction and intimidation by the judge; that right, once established, became part of our history and of our continuing and existing legal system.

International and war crimes trials are, it seems to me, very different in potential effect and can readily have a real effect on history. To explore such a proposition where might we start?

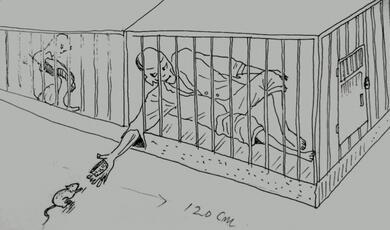

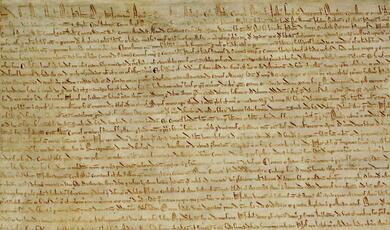

Professor James Gow of Kings College London in his forthcoming book on War and War Crimes[2] proposes the trial of William Wallace at Westminster Hall is a first example of an international war crimes trial. Edward I’s victory over his Scottish opponent in 1305 had Wallace taken to Westminster Hall. Notwithstanding the rights to proper trial enshrined 90 years earlier in Magna Carta, Wallace - with nothing more than the indictment read to him - was condemned to the most savage of deaths, imposed immediately. Although this was the very century in which the profession of barristers and solicitors developed, Wallace was without representation and was not allowed to speak. Why bother with a trial at all? The court of noblemen acting under the king’s direction no doubt reflected the sovereign’s understanding that a statement of Wallace’s crimes in a form of trial, reinforced by an unspeakably barbaric death, would reinforce the accuracy of the victor’s view of the history and better guarantee the future peace.

The trial of Petre von Hagenback 1474 is cited as one source for the legitimacy of modern international humanitarian law and can be seen as the first international war crimes trial. It can even be seen as a trial in which the origins of crimes against humanity may be found and as a first example of trial where rape was charged as a crime and any defence of superior orders was rejected.

Hagenbach was tried in Breisach for atrocities committed in service of the Duke of Burgundy before an ad hoc tribunal of twenty-eight judges from various regional city-states for murders and rapes he allegedly perpetrated as governor of the Duke's Alsatian territories. Revisionist historians tend to see Hagenbach's ordeal not as a good-faith justice enterprise but rather as a show trial meant to rebuff the territorial ambitions of Sir Peter's master, Charles the Bold.

He was convicted and publicly beheaded. But why have a trial at all?

Scholars argue that by 1474 the Holy Roman Empire was no longer a viable political entity and this unique event took place between, and can be explained because of, the erosion of medieval hegemony and the imminent establishment of Westphalian sovereignty. Sovereignty of states was thereafter not challenged by international legal mechanisms until the Versailles Treaty’s Article 227 contemplated an international ad hoc tribunal trial of Kaiser Wilhelm II post-World War I (which never took place).[3] It was only the Nuremberg trials, getting on for five hundred years later than the Hagenbach trial, that penetrated the Westphalian veil, according the case its important role as an historic and conceptual pillar of international criminal law's "pre-history”.

As Gregory Gordon of the University of North Dakota suggests, the practical political need to cast history in such a light as to see off Charles the Bold may be seen as the real reason for having a trial when it was quite possible to deal with Hagenbach without the formality he enjoyed before he suffered the death he did[4]in front of a secretive Star Chamber.[5]

The same question – why bother? - may be asked about the trial of King Charles I here in London and the answer can be found in many forms.

The "Court" had no legal authority. It was the creature of the power of the army. The King had no advance notice of the charge. No one was appointed to help him with his defence. The court did not even pretend to be impartial. Eventually the King's refusal to answer was deemed not to be a plea of not guilty (requiring the accuser to prove the charge) but a plea of guilty to treason. The King never accepted the authority of the court. He was aware, as presumably were his prosecutors, of the popular newspapers which would bring word to the people of England far from Westminster Hall, both in time and space.[6]

Although he was treated with courtesy and dignity, he was not treated with humanity. He was kept away from his family, friends and advisers. He was surrounded by guards, informers and pimps engaged by the army for surveillance.[7]

The "justice" was not "competent, independent and impartial". Nor was it "established by law". This was a revolutionary court summoned to perform a revolutionary trial in wholly exceptional circumstances.[8]

Expressed differently :

“…The trial and execution were part of the dramaturgy of state, designed to convince its audience that the text of Charles’s life must be read as reason, his death as “exemplary and condign punishment.” The high court appeal to the rhetoric of justice and divine providence to supplement or, more accurately, occlude the force underlying the trial.”

“... By staging the trial as a public display, the regicides strove to justify but also exposed to open challenge the legitimacy of their cause. … The scaffold as a theatre for punishment, twinned with the public trial, shows the force of law and justice inscribed in the very body of the condemned.”[9]

The revolutionaries may be seen to have made efforts to give a semblance of justice to the proceedings. The fact that they felt an obligation to conduct a trial at all is noteworthy. It is a reflection of the power of the trial process upon the imagination of the English people even at that time.

These trials, and at last one series of trials to come, were not legal process reflecting the rights of accused persons and victims. They were reflections of the exercise or use of power and not necessarily the abuse of power.[10] In each case, given the possibility of summary execution, a trial process was used for objectives that included or may have had as the principle component the writing of a history

In these cases we see the understanding of the power or use of trials that follow conflict, a power all us may experience today. Consider a range of nationalities. Ask yourself the question whether – in politically incorrect private thought – you reckon them to be more likely than others to commit crimes. Ask whether you regard them as more likely than others to commit terrible crimes in war. Having identified those who you disregard in this way look back and ask whether it was historians, journalists, television programmes, personal encounters or the reports of trials – national or international – that led you to, or reinforced, such politically incorrect but also dangerous thought?

Contemplation of the Second World War makes this point readily enough. Does consideration of the accused standing trial at Nuremberg – whatever the shortcomings of the overall legal process that excused the Allies altogether despite the wrongs that they may have been done, by modern standards – encourage or reinforce your view? Does the fact that there was never a possibility of leaders of the allies having their actions even considered for investigation in the way they perhaps should be today make it easier to think badly of the Germans in ways that you do not think of North Europeans generally? Yet we are not different from Germans and anti-Semitism was not remotely the preserve of the Germans alone in period before the Second World War.

In the polite society of judges in England nowadays – where most judges I meet genuinely accept the underlying principles of equality reflected in standard-setting statutes - you can hear disturbing prejudice expressed about nationalities based on the judges’ experience of numbers of particular nations appearing before them. We may reasonably assume that even if there is – for the time – a disproportion of representation in domestic criminal courts by one nation or another it is a reflection of different short-term problems in countries emerging from different pasts, not essential differences in the nature of this nation from that. Yet the trial process allows the best of judges to say the most awful of things about particular nations, happily only occasionally.

Turning back to international trials, the truth is that trials after conflicts were the exercise not the abuse of political and military power. To think otherwise would be to invest earlier times with modern notions quite inappropriately and without recognition of what is obvious. Trying the Nazis was a choice. Churchill famously favoured summary execution, just as did the citizens of Rumania once Ceausescu was at their mercy.[11]

And so to modern war crimes trials. Has the potential to try all sides of conflicts in the modern era of codified rights of accused and of victims changed or limited the way trials may shape history? Is it reasonable to expect modern states to act differently in their approach to trials after conflict than their predecessors did?

First, however, we must recall that all judges at all these courts do say that they do not write history in their judgments - and they don’t. This was noted by the ICTY Chamber in the Kupreskic case when the Chamber stated that:

‘the primary task of this Trial Chamber was not to construct a historical record of modern human horrors in Bosnia-Herzegovina. The principal duty of our Trial Chamber was simply to decide whether the six defendants standing trial were guilty of partaking in this persecutory violence or whether they were instead extraneous to it and hence, not guilty.’[12]

Former ICTY Judge Patricia Wald made the following observations:

“Initially the Tribunal was urged to make detailed findings about the social and political etiology of events leading up to the atrocities on trial. This, it was suggested, would provide an antidote to revisionist history by preserving adjudicated accounts of what actually happened in the foreplay to the Bosnian conflict. As a result, dozens of pages in ICTY judgments focus on the causes and precursors of the 1991 outbreak of hostilities. However, commentators, citizens, and officers of the implicated countries increasingly suggest that the adversarial trial process and the findings of judges may not produce the best approximations of history. Moreover, the ‘‘adjudication’’ by ICTY of who started, prolonged, or ended the war and why in the context of criminal proceedings without the states themselves having input is basically unfair, or at least does not contribute to future reconciliation.”[13]

However, these understandings say nothing of the power of the trials to write history, no matter what the judges may say, of states involved in trials; and nothing of the use states may make of trial processes,, or trials themselves, to write history as they choose it to be.

Rwanda and Other Africa conflicts discussed in my last lecture showed how the courts can be engaged in a cynical way to become instruments of conflict; that is itself a method of writing one sided history.[14] If one side of a conflict gets the court to prosecute only the other side – the Hutus of Rwanda , for example - then writing a balanced history, leaving behind a balanced history, of the conflict will always be a much more difficult task.

Returning to the Yugoslavia conflicts what lessons may we learn from a consideration of this issue in the context of what is the most successful of the recent family of international courts. The statute and the rules of the ICTY oblige states to cooperate in all ways with the Tribunal in the surrender of individuals and provision of documents but then go on to provide a regime – as applicable to one of the states formerly in conflict as to a ‘stranger’ state like France or the USA – that allow the greatest possible delay in provision of documents.

How could it ever have been realistic to expect a court system stuck in a remote Northern European country, with no police force and limited powers of securing documents from states that had been at war, to rely on the good will of states to help in the production of documents to prove cases against their own nationals? About as realistic as expecting a bank voluntarily to provide incriminating emails about LIBOR fixing to be used against its own executives rather than to use delaying tactics, if available, that might allow it to postpone provision for three to even five years during which time other documents could be produced and originals destroyed.

The Tribunal’s Rules allowed in principle for every conceivable tactic by Serbia (and no doubt other 3rd party countries) to avoid handing over what might have been interesting and the judges did not seem keen to cut the red tape and allow the prosecution to race to the vault.

Many would argue that from the start of the Yugoslav Tribunal (the ICTY), Serbia knew that it had to take it seriously; not in order to assist genuinely in the prosecution of serious offenders but in order to do what it could to preserve its, Serbia’s, long term reputation to the extent possible. Serbs had been assessed by almost all independent observers as having committed the most, and the most serious, of crimes in conflicts where some six states and entities were involved. Serbia may have wanted to create wherever possible some kind of moral equivalence with those other parties to the conflicts and in this way to rewrite its history and the history of others, in particular the histories of Bosnia and Kosovo.

When documents were provided it was found that they were selected in a way that was not responsive to the request made or to be exculpatory for Serbia or for the accused concerned.

This assessment of the cooperation by the Prosecution prompted the following answer by Serbian state legal representative:

“I wish to emphasise that we have not provided new excuses but instead we have raised perfectly legitimate objections under Rule 54 bis (A). Of course Serbia and Montenegro has the right to do so under the Statute and Rules, and in this the government is indeed an adverse party to litigation as any other government would be and has been in a similar procedure. Of course this does not mean that the government is not assisting the International Tribunal as the Prosecution contends. The Prosecution may or may not agree with our objections, but it has no right to accuse of bad faith and non-cooperation a state that is fulfilling its obligations under the Statute, and it exercises its rights under Rule 54 bis. This is even more so when the state Serbia-Montenegro was actually following what was ordered by this Chamber…”[15]

When rejecting the notion of non-cooperation, the Serbian legal representative reminded the Court that Serbia was following the Court’s orders, and the Court’s excessive respect for Serbia allowed them to assert this. When deciding on ordering the production of the documents listed by the Prosecution, the trial Chamber ruled against production of critical ‘war diaries’ as ‘overbroad’, when - as emerged - they were easily identified documents sitting on an archive shelf and of immense potential value to the Tribunal’s trials.[16]

Serbia rejected the implication of the OTP’s statement that the government was hiding or withholding evidence for the trial, by stating that Serbia had been cooperating despite a heavy toll:

“It should be remembered that it is this government that arrested and surrendered Mr. Milosevic in the first place. It should also be remembered that Mr. Djindjic, who was prime minister, took responsibility for this act, was assassinated in March, and at the same time from the investigation into his murder, it has transpired that there has been a further list of targeted officials, prominently including certain ministers responsible for cooperation with the International Tribunal. To suggest in these circumstances that the government is actually withholding evidence is quite cynical, especially if one compares the armchair perspective of the Prosecution with the tangible challenges faced by the government.” [17]

The informal answer to this might have been ‘so what’! It was to ensure that defendants surrendered to the Court were properly tried that the documents of the Serbian state were so important.

Much of what follows is drawn from the forthcomingpublication, cited above, by Nena Tromp - who was researcher in the Milosevic trial throughout – titled "The Unfinished Trial of Slobodan Milošević: Justice Lost and History Told".

General Delic explained how the preparation of his own testimony took place. He first received a list of events from the Commission and he was asked to deal with them in graphic and textual form. In order to do that the VJ Commission provided access to all contemporaneous documents he needed to prepare for his testimony. To demonstrate how well prepared he was, he showed to the Court the copies of the operational logs and the war diary of his brigade he took with him to The Hague. The Prosecution identified them as some of the very documents it had sought from Belgrade and Delic was compelled to hand over the war diary despite his protest. Delic initially claimed that the reason why the Prosecution did not get any of the contemporaneous VJ documents was simply because the Prosecution had never requested them[18]

‘… You didn’t say the war diary of 549th Brigade. If you had requested anything specifically from my unit, I have nothing to hide. Every document should be accessible to you if my state should decide so.

Eventually, he was compelled to accept that the Prosecution had requested many contemporaneous military documents via official channels including those relating to his unit, protesting to the end that “they asked for the documents of practically the whole army, referring to the whole army. What they should have done was to ask specifically which document they were interested in: which unit and which specific document.”

Why should the prosecutors at The Hague investigating such grave crimes have been limited to asking only for what they already knew might exist when their duty was to investigate grave crimes thought, justifiably, to have been committed by bodies that held their own original records of what they had done?

The ICJ worked on the basis of the blacked out documents and declined to ask for the full ‘un-redacted’ version. The court’s decision, delivered in 2007, was a profound disappointment to Bosnia. I am grateful to Phon van den Biesen, counsel for Bosnia, for slides that summarise how close Bosnia got to a result more satisfactory for its citizens.

In a tantalising judgment the court went step by step towards, but stopped short before, a finding of genocide or of complicity in genocide. It made this decision, arguably, because it had been deprived of material that would have filled the gap; some argue that what lay behind the blacking out of the SDC records could have been enough to have brought a different verdict. Of course it is always possible that political influences were at work in the minds of some of the judges at the ICJ, for all international courts have such vulnerability asserted against them, but what is certain is that the processes that allowed Serbia to manipulate or control evidence did much to allow this unsatisfactory verdict to emerge.

What can Bosnia now do? It could seek to re-open the case - there is still time for that to happen. It could rely on further evidence that is now available? - and many hope it will. However, the litigation history to date – and any litigation narrative to come – must acknowledge that courts which can only act on evidence available at the time of their judgment and that they are largely at the mercy of states when it comes to getting their hands on relevant documents..

Finally to Kosovo – a case study not just in what can be achieved by a state within an actual trial but what mere exposure to investigation of those in conflicts can offer. Kosovo was the beginning and end of the Balkan wars of the 1990s. Milosevic devoted a great deal of the time allowed him by the court to deal with Kosovo and needed to make the Kosovo Albanians out to be as bad as could be in his own defence. There was - as explained earlier – active support for him at government levels in Serbia, as a minimum when it came to cooperation or non cooperation with the Tribunal over production of documents. Did that support go further?

For whatever reason, an allegation was made in 2003 to the Tribunal’s Prosecutor during the Kosovo segment of the Milosevic trial that Kosovo Albanian leaders had in the late 1990s been organising the execution of Serb prisoners in Albania to harvest their internal organs for sale on the black market. The allegation, once it surfaced, was as improbable as the one Churchill advanced in WWII about Russians eating their babies – until the Russians became our allies and he had to correct the propaganda. It is exactly the sort of story heard often in war, but it was being made against leading Kosovo Albanians; including their then prime minister Ramush Haradinai.

Papers have since been leaked in various forms and show obviously genuine ICTY Prosecution documents and internal reports of various kinds constituting an investigation into the allegation. On analysis there is nothing in the leaked paperwork that justified the otherwise unsupported allegations of organ harvesting and, as a result, the investigation came to nothing.

I knew nothing of it at the time although I was to discover how strong were the forces determined to have Haradinai charged with and tried for war crimes. He was eventually tried (nor in respect of the harvesting of human organs) and acquitted, then retried on very dubious grounds for the same allegations, to be exonerated yet again. That is another sorry story. Haradinai surrendered himself to The Hague immediately he was indicted and, of some significance in what follows, Hasim Thaci became prime minister.

Once the Chief Prosecutor – who had been so determined to have Haradinai charged – left office she published a book in which this unsubstantiated allegation was raised again – but this time and for no accountable reason against Thaci, who barely featured in the pages of the original documentation (that had yet to be leaked to the press).

Later still the Council of Europe became involved and launched an investigation which sought to find substance to back the allegations against Thaci, still the serving Prime Minister. Some say the Council of Europe is dominated or heavily influenced by Russia and Russia is, certainly, Serbia ’s ally.

Kosovo seeks practical confirmation of the independence it took from Serbia and Serbia would no doubt like to discredit Kosovo’s application to become a full UN member and a member of the European family of States.

The allegation in the Council of Europe was made by a former Swiss Prosecutor called Dick Marty who has since been the subject of bruising encounters with EU Parliamentarians over the quality of the report he presented and the evidence on which he relied, which was substantially the same evidence that came to nothing in 2003. The first publication of his report before the Council of Europe coincided with the first leaking of the 2003 ICTY documents concerning the allegation. At this first leaking the documents were heavily redacted in black ink, and nothing is as good as a blacked out document to raise suspicions, in this case among the members of the Council of Europe?

It was only later that the un-blacked out –un-redacted if you prefer - documents appeared when they could be seen to contain neither compelling evidence of the alleged crimes, nor any mention of Thaci. And there was no evidence of substance additional to what was first seen and rejected as inconsequential in 2003.

One would think the full disclosure of these documents would see Thaci publicly exonerated at least in the court of public opinion in the way his predecessor has now been acquitted in court. Not at all. Further official UN investigations continue and he remains tethered by a rumour that would have got nowhere at all had it not been raised within the seeming solemnity and seriousness of a Tribunal process. To date not one piece of eyewitness testimony or forensic / scientific evidence has been produced to support the organ harvesting, yet Thaci finds himself forever tainted by the rumour and unable to prove a negative. The rumour, and the lack of investigation into the origins of the rumour, taint all Kosovars and play into the hands of those who are determined to see its claims for full statehood thwarted.

And who raised the allegation? - Little doubt. The same body that revives the allegation whenever it needs to in its pursuit of leaving a record of moral equivalence with the David that stood up to its Goliath.

What out of all this? Nothing, if it is accepted that victory in conflict allows the victor to take all prizes including the prize of setting the record; nothing if trials for conflicts are treated as conflicts themselves. Victors or vanquished should be allowed to do all they can according to the rules of the game to create what record they like.

Where in earlier times trial processes were used by victorious states to achieve political objectives of pretty straightforward kinds, modern war crimes trials can be sued by any involved in ways that can affect or corrupt the setting of a record of events, the very history of what happened

If modern trials are driven by objectives of long term reconciliation not just of victory in conflict, and if trials are being conducted according to concepts of human rights for victims as well as for perpetrators then there are problems revealed here of which we need to be aware.

And what can Bosnia or Kosovo do to redress imbalance they say harms them and will or may harm their future?

The following conclusions may emerge:

Those of us reading about these international trials can work on the basis that the lawyers and judges are doing their best with the material available to them but would be wise to keep in the backs of our minds that there may have been significant political manipulation of what has been made available

Those who establish these courts and trials - the UN and the ICC - might have as a priority establishing systems that will allow documents to be obtained in hours or days not in weeks, months and years and for documents obtained to be made public to the maximum extent possible as early as possible. That may mean that obtaining documents (and witnesses) should be an active responsibility of the political body that establishes the court and that may have the ability to sanction a country for non-compliance.

Countries turning to courts to leave accurate records of conflicts should understand the limitations that court decisions inevitably involve. They should recognise that it is the responsibility of a country that has been in conflict to ensure that an adequate record is left of its own history - whether by Truth Commission or modern computer assisted evidence projects - and that if it does not take this responsibility subsequent generations may hold it responsible for whatever may follow from its history being inaccurately recorded.

Due thanks to Haydee Dijkstal, for her assistance in research for this lecture.

© Professor Sir Geoffrey Nice 2013

[1]Arendt, Hannah, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, 1994, p. 243.

[2]Gow, James, War and War Crimes, London: Hurst, 2013. The idea was first suggested to James Gow by a Scottish colleague of mine at the Yugoslavia Tribunal Gavin Ruxton

[3]Versailles Treaty. See, http://net.lib.byu.edu/~rdh7/wwi/versa/versa6.html.

[4]Hagenbach’s inter-regional depredations, which helped forge a rare pan-Germanic consensus, provided the perfect forum to experiment with international justice during that fragmented time. Should the nation-state ever manage to reassert its absolute supremacy again, Breisach will undoubtedly be on the lips of future international jurists seeking, as before, to end impunity at the expense of sovereignty

[5]Prof. Gregory Gordon of the University of North Dakota law school University of North Dakota - School of Law February 16, 2012

[6]The Trial of King Charles I – Defining Moment for our Constitutional Liberities, by Hon Justice Michael Kirby AC CMG, 22 January 1999.http://www.hcourt.gov.au/assets/publications/speeches/former-justices/kirbyj/kirbyj_charle88.htm

[7]Ibid.

[8]Ibid.

[9]Paradise Regained and the Politics of Martyrdom, Laura Lunger Knoppers, Pennsylvania State University.

[10]See generally, Paradise Regained and the Politics of Martyrdom, Laura Lunger Knoppers, Pennsylvania State University. http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/438752?uid=363442041&uid=3738736&uid=2134&uid=4578141157&uid=2&uid=70&uid=3&uid=67&uid=62&uid=4578141147&uid=18828976&uid=60&sid=21101774494837.

[11]And was the trial of Saddam Hussein – for which I had indeed pressed when a member of an NGO gathering evidence against him – really much different from summary judgment with something purporting to be a trial between capture and execution?

[12]Oral Summary of Judgment, Kupreskic et al. (IT-95-16-T), 14 January 2000, pg 12972

(http://www.icty.org/x/cases/kupreskic/trans/en/000114it.htm).

[13] ‘The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia Comes of Age: Some Observations on Day-To-Day Dilemmas of an International Court’, 5 Washington University Journal of Law & Policy (2001) 87

http://law.wustl.edu/harris/documents/p_87_Wald.pdf

[14]The permanent International Criminal Court – the ICC – and Africa, 31 October 2012 (http://www.gresham.ac.uk/lectures-and-events/the-permanent-international-criminal-court-%E2%80%93-the-icc-and-africa).

[15]Ibid. (See footnote ICTY Milosevic Trial Transcript 216616:13-21667:21.)

[16]Ibid

[18]Ibid

Part of:

This event was on Wed, 13 Feb 2013

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham College plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login