Should We Trust The Scientists?

Share

- Details

- Text

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

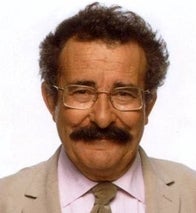

The 2005 Gresham Special Lecture was given at The Great Hall, Guildhall, delivered by Professor The Lord Winston.

Introduced by: Lord Sutherland of Houndwood KT, Provost, Gresham College

This was the 2005 Special Lecture. Other Gresham Special Lectures can be accessed here:

2013 - The New Face of Europe by Sir Richard Lambert

2012 - Parliament and the Public: Strangers or Friends? by The Rt Hon John Bercow

2011 - Reinventing the Wheel by Sir Adam Roberts

2010 - The Challenges of the new Supreme Court by the Rt Hon the Lord Philips

2009 - The Ascent of Money by Professor Niall Ferguson

2008 - Early Christianity and Today by the Archbishop of Canterbury

2007 - The Beauty of Holiness and its Perils by Sir Roy Strong

2006 - Walking the Line by Baroness Kennedy of the Shaws

2004 - Science in a complex world by Sir Martin Rees

2002 - Towards freedom from hunger by Professor M S Swaminathan

2001 - Commerce and Culture in the Late 20th Century by Professor Charles Saumarez Smith

2000 - A Global Ethic - A Challenge for the New Millennium by Professor Hans Küng

Download Text

SHOULD WE TRUST THE SCIENTESTS?

Professor Lord Winston

Introduction by Lord Sutherland of Houndwood

Gresham College was created by the will of Sir Thomas Gresham, and it was to make available in the City of London, learning and education, to those who lived and worked in the City, Sir Thomas’ great passion. One of the ways in which we commemorate all that he provided for Gresham College is to have an annual Special Lecture, and this is it this year. The College has various sources of information available to you. Our lectures in the College are all web-cast, and we hope that for those of you for whom this is a new link that you will continue wanting to know about Gresham, but more importantly, what our magnificent professors and lecturers offer to us.

This evening I’m very pleased to welcome Lord Winston. Lord Winston is of course a very distinguished academic and researcher. He has been a remarkable physician in one of the most difficult and most sensitive of areas, and he has, in the area of fertility studies, practised medicine as one hopes a good medic would. But of course to many of you and to most of us, he is now known as a marvellous communicator and broadcaster, someone who can take the message of what science and medicine can do for our civilisation out into the wider community and do that in remarkable ways.

The topic is fundamentally important for our age. I’m sure Sir Thomas would have approved that this is something on which we want to deliberate, so I ask you to welcome Lord Winston to lecture on “Should we trust the scientists” – Lord Winston.

Robert, Lord Winston

If you look at the painting by Pieter Brueghel the Elder depicting the Tower of Babel, it shows a 13 storey building, stretching up to the sky, with King Nimrod directing operations. The place is crawling with people, with galleys and pulleys and masons, workers of all sorts, cranes, and when you look in detail, the thing that’s obvious is that the building couldn’t possibly work because in fact the rooms are built on a kind of helix and couldn’t communicate with each other and there would be no way of getting access to them. You’ll know the story very well of course: God confounded man’s arrogance and ambition and threw the celestial spanner in the works, and changed their language so they couldn’t talk to each other, and the project died, a bit like some of the Private Finance Initiatives!

I was reminded of this recently going to CERN, where there is another Tower of Babel which is currently being built, also about 14 storeys high, but this one is underground. What the physicists are doing is to use the speed of light to try and get protons accelerated to crash into each other and produce ever and ever more mysterious particles, particles that would have been started at the time of the Big Bang. What they’re trying to do is re-convene, if you like, the first few milliseconds of Big Bang, when presumably God either was or was not in existence. The interesting thing is that they’re after the Higgs boson, a curious particle which if it exists proves that modern physics is absolutely right and that most of modern mathematics stands. If the Higgs boson doesn’t perform and doesn’t materialise, then modern physics has a real problem – God will have thrown another spanner in the works. It’s an interesting example of a modern Tower of Babel. It’s an international project, which we in Britain, along with other countries, fund.

I am very interested in Brueghel because Brueghel was very concerned about technology. If you look hard at many of his paintings, and many of his drawings, you see this theme recurring. Mankind is thought to have begun in the Rift Valley in Kenya. It’s the place where the early hominids roamed on the savannah. Skulls have been found there of Australopithecus aferensis, and of Homo erectus. The fundamental difference between the two early pre-humans, spaced about 3.9 million and less than 3 million years ago, is that in the space of a million years, the human brain substantially increased in size – it doubled, from about 450 millilitres, a bottle of milk, to 900 millilitres. Modern Homo sapien now has a brain size of about 1,450 millilitres. It’s a bit less for the ladies because they’re prepared to ask the way when they get lost, whereas men need a bit more brain because they go on aggressively driving, trying to find their way, and remembering the turning they took!

Anyway, whatever the reason for the difference in size between the sexes, and it’s not obvious, there is a major puzzle here, and that is this extraordinary expansion of the human cortex in really probably around a million or so years. Homo sapiens we believe has been on the face of the Earth for about 100,000, maybe 150,000 years, let’s say for the sake of argument. I have drawn a timeline representing the last 50,000 years, the time that man has been on the planet.

By comparison, if we draw another line, in the same space of time to the same scale, in that space of time, something has happened. Although we had the entire genetic structure, all the genes which make up the human brain, for the whole length of that large timeline, in that fraction of time, what has happened is that we’ve invented printing, we’ve written Hamlet, the B Minor Mass, we’ve made the steam engine, we’ve built computers, and we’ve landed on the Moon, in the space of 500 years or so. That is extraordinary. The thing I want to draw to your attention is that whilst the human brain has probably hardly changed at all, there has been a massive change in the human mind, and that I think is a fundamental problem to our society today. It’s one of the reasons why we are so concerned about technology because it is now no longer, as it was in Shakespeare’s time, possible to predict what will happen in the next decade. That is a fundamental uncertainty which has only existed in our recent lifetime.

If you look at the greatest idea that mankind has ever had, it must be surely this: it wasn’t the invention of the wheel, it was the recognition that a flint stone, which we’d known about and carved through a million years before Homo sapiens was on the Earth, could be fitted into a stick, which we know that apes use as levers today – the chimpanzee, the gorilla, and so on – but fitted in a stick, this becomes an amazingly different tool. It becomes a lever, a weapon, a spear, an axe, and increases man’s ability to overcome his fragility on the savannah in an extraordinary way. Before that time, he’s a helpless species. He has very little chance of defending himself. After that of course, he can hunt as well as scavenge, and that makes a huge difference to mankind’s ability. It is extraordinary and it’s a great puzzle that it took a million years for somebody to think of that trick, and I still don’t understand why that should be. It must have happened simultaneously presumably in many different places.

We live in a scientific world which is somewhat at siege: look, for example, at nuclear power, nuclear waste disposal, global warming, BSE and CJD, our miserable response to foot and mouth disease, which cost the country something like £3 billion, the shocking debacle over genetically modified crops, the attitude towards cloning humans, or the response to the triple vaccine. This response has left something like a vaccination limit of some 60-65% of inner city Britain in parts, therefore a large vulnerable population to measles, which is, make no mistake, a killer disease, and although we’ve been very fortunate and not had an epidemic, the suspicion about the vaccine could well have caused it. I can tell you for certain though, in my own field, that in the next few decades, there will be many men who find themselves infertile as a result of the failure to take up that vaccine because there has been a mumps epidemic which has not been reported in the press. We also face very curious qualms over animal experimentation, and I will spend a little time on embryonic stem cells, simply because these cropped up again in the newspapers this morning, and it seems only right that I should address that issue with you this evening.

Let’s look at public trust in general. Well, it turns out that doctors are trusted, teachers are trusted in our society, amazingly, TV newsreaders are trusted, but not journalists – maybe it’s something to do with the level of pay that we now know that newsreaders achieve. It’s rather nice to think, because there are quite a few in the audience, that professors score better than scientists, though often of course some professors really reckon that they are, or at least at one time were, scientists! Right at the bottom of the league.come government ministers, politicians generally, and people who are spin doctors and journalists. That public trust is interesting, because although scientists still scored pretty well in a MORI poll, what we do not trust, necessarily, is the science which comes from the scientists, and I think we need to ask ourselves why this is and what the consequences might be.

I suppose it’s fair to say, certainly if you listen to Sir David King, the Government Chief Scientific Advisor, that the greatest single problem facing mankind today is global warming. I think the evidence now that this is manmade is almost, in my view, overwhelming, and I think most scientists, certainly 95% of them, would agree with that evidence wholeheartedly.

The sudden rise in carbon dioxide, which is the main global warming gas, has reoccurred since the Industrial Revolution, mainly in the last 150 years, and the heating of the globe is now undoubtedly obvious, and it’s quite clear that it seems to be unprecedented with this unique cause. It cannot any longer be ascribed to mere fluctuation or the way that the Earth wobbles on its axis in relation to the Sun’s rays.

What I think is interesting is the way our leading broadsheet newspapers talk about global warming. One reported: “The warnings come from the climate change industry, which is a great racket to be in. It’s a global employer of millions – politicians, scientists, eggheads, civil servants, ecologists, egged on by green talents and assorted single issue fanatics, and they’re all doing rather nicely, thank you, with no product to sell except fear.” That is such an irresponsible way of reporting scientific evidence that it should make every one of us very seriously alarmed, because in our children’s generation, if global warming continues at the present rate, we will see whole cities flooded and uninhabitable, including our own city of London. It is a very serious problem, if the melting of the icecaps continues as is predicted, and whether or not it affects Great Britain, it is undoubtedly true that certain deltas in the world provide a major risk. People will be wiped out in the Nile Delta, millions of people, and millions of people will lose their livelihoods and homes, and their lives too probably, in the delta in Bangladesh. So this is something which we need to take notice of, and the response is I think very curious. When you look at the Royal Society’s report of 1999, it’s very clear that we do not intend to curb our energy usage. Indeed, the developing world is predicted to increase its use of energy, most of which will be coal and oil fired, by seven-fold. In places like China, and India this is already happening. And why shouldn’t they? After all, we went untrammelled with our burgeoning improvement in domestic product; now it is the turn of the Far East.

By the same token, we are refusing to consider any new nuclear power stations or any nuclear power generation. I know we’ve heard about wind farms and many other forms of energy source, but the evidence would suggest that none of these, when you come down to it, is as effective or as reasonably priced for what they will give, and as safe, as is nuclear power. Whether or not that is a true statement in a sense doesn’t matter. What is truly worrying is that we still do not have intelligent debate about the use of this safe source of energy in this country. That I think is shocking, and it is because governments are too frightened to worry public opinion.

This is the House of Lords Select Committee publishing last year, in July: “Overall, it seems to us, talking about renewable energy, particularly wind power, in parallel with other developments, the Government may have no option but to follow the lead of other countries and accept that in the words of the White Paper, “New nuclear build might be necessary”.” That, if anything, must be an understatement, and a very modest one at that. Modern nuclear plant is safer and more reliable than our present elderly installations and produces less waste. There are public concerns about nuclear build, but there are also concerns, as the report shows, about wind farms.

What was the Government’s response? Well, in its response to the Lords Select Committee, it doesn’t even mention this paragraph, and nor did we expect it to, because it has consistently failed really to deal with the issue in a way which is satisfactory, and certainly there is no attempt at public engagement.

So here I think we see a failure of leadership from government. Here’s another problem for trust in science: the protest against GM crops. The prejudice against GM is, and it is to some extent prejudice, is one that resulted in their failure of any proper and accurate debate. This I think, this was not government’s fault. Rather it was because there was a perception by the public that there were commercial ambitions driving genetically modified crops, that there was no advantage to you and me in developing them, so why should we risk anything in our environment, quite rightly. Consequently we failed to do anything about it. What we might have done was to recognise that at the 1994 Consensus Conference –11 years ago – when the public was raising its fears, none of those fears was engaged.

The prejudice was led, to some extent, by His Royal Highness Prince Charles, who is a delightful and humorous individual, but it is interesting that he does actually have something of a vested interest as an organic farmer, one that was never declared, which would be unthinkable I hope for a scientist, not to declare an interest in whether or not one has genetic modification.

What I think is worrying is not Prince Charles’ response so much as the fact that so much of the response has been simply on a basis of gut feeling and prejudice. Thank goodness his sister obviously didn’t feel the same way. She’s been to Africa, and she’s been to Asia, and she’s seen children dying. The malnourishment on the planet on the whole is truly scaring. One third of Africa is receiving a diet which is below starvation level. It has improved a bit in some countries. Somalia has got worse, it’s probably got worse in Afghanistan since the war, it’s got worse in Korea, it’s got better in India, but 22%, 220 million people, at starvation level should give us cause for thought.

I’m not saying for a moment that genetically modified foods will deal with that issue. Clearly, that would be a falsehood. There probably is enough food if we managed the world’s resources better, but we still have a rising population; we still know that if we’re going to feed people properly, world food requirements are likely to double. There’s a continued decline in staple foods like cereals, and 40% of our food requires active irrigation, against the background of course of global warming and less predicable weather.

Many of us will be wearing cotton shirts. One kilo of cotton requires 8,000 litres of water. The food that we eat, the edible plants, 40% of these are lost to pathogens, to bugs, bacteria, viruses, and mostly when they are already mature, consequently once they have already used their entire complement of irrigated water.

We know that with genetic modification we can do two things. We can make plants resistant to disease that would normally kill them, and we can also make plants resistant to drought. I do not pretend for a moment that this is going to solve India ’s problems, but it is certainly ridiculous to exclude the research into this in the country which is most able to do it – mainly the United Kingdom, which has got such a fine track record. We cannot even run field trials because of the public anxiety and the public activity which has prevented this very consistently in the last two or three years.

I recently visited an orphanage in Kenya where I took photographs of many children, all of them dying, all of them infected with HIV. The little girl who sat on my knee is now dead; the little boy, whose face I painted, is now dead. There are 300,000 children who are orphans as a result of HIV in this part of Africa alone. These children are lucky because they’re in an orphanage, which is rare, very rare, an orphanage which is supported by people like ourselves. Most of these children are severely malnourished, and the malnourishment is the one thing which makes the spread of all these infections and their effect much more serious, and that is something which should be a matter of considerable shame when we eat and live so well.

Let me turn to another example of why I think there is an issue over public trust. Many of you will have heard of Phineas Gage, because his injury was so extraordinary that it occurs in about 60% of all neuroscience and neurology textbooks. In 1848, on a sunny afternoon in the middle of September, Phineas Gage was managing a gang of men on the Cavendish Vermont Railway, which was driving in the direction of Cavendish from the Boston area in Massachusetts. The idea was to blow the shallow floor of a tree-lined mountainside flat so that a track could be laid. The principle was this: that the men would drill a hole in the floor, they would place the dynamite in the hole, they would then place a detonator on top of the dynamite in the hole, and then somebody would come along, pour sand into the hole, and Phineas Gage or one of his employees – sometimes Phineas Gage himself because he designed the tamping iron – would bring the tamping iron down on top of the sand to compact the charge. They would then retire behind a suitable tree or a rock, blow the charge, and blow the floor.

In fact, they were within a mile and a half of Cavendish when the famous incident happened. Phineas Gage, in a moment of untypical mis-attention, brought the tamping iron down on a charge before the sand had been put in the hole. The resulting explosion blew the tamping iron out of the ground, through the left side of Phineas Gage’s face, took out his cheek from behind the cheekbone, behind the eye, taking out the left eye, and exited through the left of his head. The tamping iron, which was about four feet or so in length flew and ended up 100 feet behind Phineas Gage. Phineas Gage was thrown backwards in the air for some yards, landed on his back, and lay there.

What was remarkable was that Phineas Gage, who was really loved by the workmen because he was regarded as being an excellent boss and a very good foreman and totally responsible and a very nice character, was lying there, still conscious. He could speak. He could see, with his remaining eye. He was able to say that he wasn’t in a great deal of pain. He could move all four limbs. He was totally conscious and, most remarkable; he had memory of what had happened. He was taken on the dog cart the one and a half miles into Cavendish, where a remarkable young doctor, John Harlow, administered first aid to him, expecting him to die. Phineas Gage said to John Harlow, “Here doctor is work enough for you!” John Harlow records this in the Boston Medical Journal when he wrote this case up some years later.

Phineas Gage, remarkably, recovered. He never lost consciousness. He never lost his memory. He never lost sensation. He was able to talk perfectly lucidly. He could still think. After six weeks, he was up and about. The problem was that Phineas Gage now was no longer Phineas Gage. He was now a totally different person. From being a remarkably responsible and friendly individual, he became aggressive and domineering. Before, his relationships with both men and women were exemplary; now he used every attempt he could to make sexual advances at both men and women. He was irascible. He shouted. He was completely unclear what money was for. His whole attitude to life was one that made him unemployable. He tried to go back to his job, but his employers finally had to get rid of him, and he went wandering. He ended up in Chile as a horse trader, and finally made his way back after 11 years to California, where he died.

There is a photograph of Phineas Gage’s skull in the Harvard Medical Museum, because when John Harlow heard of his death, he had him exhumed, some five years later. I don’t know how he got permission. I think it was probably easier in California than it would be under the Human Tissue Act in Britain ! However, the skull was preserved, together with the tamping iron, which is still present in Boston.

What is interesting is the injury that it caused. It caused effectively a prefrontal lobotomy, which is what destroyed Phineas Gage’s soul.

Egas Moniz almost exactly 100 years later won the Nobel Prize for reproducing this injury in patients who either did or didn’t give consent but who were suffering, or weren’t suffering, from some form of vague mental disease. In many cases, it is not even documented what exactly the operation was done for, but Egas Moniz received huge acclaim for his remarkable use of this operation, because what it did was to make people, on the whole, unlike Phineas Gage where it went the wrong way, more amenable, who would just sit there without complaining, often vegetables. Of course by this time, don’t forget, Phineas Gage’s injury was well documented. It was in the textbooks. That didn’t stop this prize being awarded.

What is particularly scandalous are the actions of Walter Freeman, a surgeon in the United States who, seeing the glory that Egas Moniz got, tried to imitate what he was doing, and started to do prefrontal lobotomies in various States around the USA. He became a travelling surgeon. In the operating theatre he did not wear gloves, not wear a surgical gown, had no mask. The patient was being held down. The only anaesthesia that was given was an electric shock administered by Walter Freeman’s son. And Walter Freeman, in order to demonstrate his remarkable expertise, used a hammer which had had taken from the surgeon’s cocktail cabinet, which was normally used to crack ice, and he drove this pick through the inner eye. He did some 3,000 operations like this, including one operation on JFK’s sister, who remained a vegetable for the next 50 years.

No proper peer review was done. No proper regulation was undertaken, and the result was the burgeoning of an operation which was never evidence-based. This is a shame – a medical hubris. So it can happen even in that most respected profession, according to the MORI poll, but I think the response to our responsibility is one that is very important as scientists.

I’d like to take my own field now.

In 1990, Alan Handyside and I devised a trick by which we could remove single cells from embryos, and do something which at the time was entirely novel. A little dose of acid was used to drill a hole through the shell of the embryo, so that we had access to the cells inside, from which we could take one or two cells and make a diagnosis based on the DNA of the embryo. The removal of a cell like this is completely harmless. A great deal of animal work demonstrated that this was a safe thing to do, and this is a technique which has now gone worldwide. It’s used in a very large number of countries, except Italy recently because of the change in the legislation there, and there’s some nervousness about it in one other country in Europe, in Germany, for various reasons. But broadly speaking, this method of genetic diagnosis is one that is interesting, and whilst I don’t want to exaggerate its importance, because I don’t believe it is that important, I think that the response to this is one that is extraordinary and does tell something about trust in the science.

As soon as this was published these embryos were called perfect babies or designer babies. Lisa and Harriet were the first babies in the world to be born – they must be now just over 15, 15¼ - and Lisa is far from being a perfect baby, she’s got this blemish on her chin because she fell over about eight hours before the photograph was taken! But what’s important is that they are not designer babies. They are not perfect babies. The reason for this diagnosis was because their elder brother, aged four, died of adrenal leukodystrophy, and the mother felt that it was unethical to consider abortion of an affected boy, or a boy that they couldn’t diagnose the disease in, and decided she wanted to go for DNA diagnosis. All the difference between these babies and any other siblings that might have been born is literally one base pair difference in the entire genome. Bear in mind that each of us has over three billion letters in our genetic alphabet, so the difference between them and their brother is one base pair that we were able to detect. So these are not designer babies. The rest of their DNA is entirely random, as it always must be after this technique, but most of you reading the press would never fully appreciate that, because it has been portrayed in such an extraordinary light, really very negatively, in some ways, rather like the cloning issue.

The role of the media in public trust in science has been, sometimes, rather outrageous, some newspapers being worse than others, but I think it has now got to the stage where, frankly, most people read the Daily Mail more for entertainment and enjoyment than for getting a serious opinion about what is happening in the world – at least I hope that is true, but it is worrying nonetheless. The print news media on the whole do not come out of this whole saga with great glory. When they report science, on the whole, it’s reported on the following pretexts: is it a breakthrough? Science is never a breakthrough. Scientific knowledge is made by incremental, slow pieces of information which come through. Nothing is ever truly original.

Journalists ask: where is the controversy? Then it’s worth reporting. Are the scientists arguing with each other about it? Is it topical? Is it British? That is the issue today with regard to the stem cells, the sperm cells and egg cells, which you read about in The Times and The Telegraph. Of course the fact is that that’s been done elsewhere in the world for several years, but because it’s British and came from Sheffield - Sheffield is a fine city, by the way, those of you that don’t know it, and I have a particular connection with one of the universities there of which I’m very proud – but this is where this work was done.

Do you have public responsibility? That was the case in MMR. The fact was all the evidence showed very clearly that there could not be any serious connection between autism and the injection, but the Daily Mail regarded it as their public responsibility to report a negative “finding”, because of course they had what they thought was a moral obligation. Where’s the entertainment value? Are there any pictures? And is a celebrity involved? This is a truth, to some extent, about much of the print news media, and it is sad particularly because I have to say that we have some of the best science journalists in the world – people like Roger Highfield, Steve Connor, Tim Radford are outstanding individuals, but the problem is that the agenda is not driven by them, it’s driven by the newsroom and by the editors of the paper.

Dolly the sheep is of interest. It is a very interesting question…why is Dolly the sheep of such interest?! Why should there be such an extraordinary issue over cloning, when actually, in spite of the hype, there’s really no evidence, that Dr Zavos has actually really seriously contemplated doing human cloning? We know that pretty well all the animals that have been born after cloning are abnormal. The risk of producing an abnormal human must be monumentally high. It would be unthinkable for any scientist, or doctor, to consider doing that in the current litigious world we are in. The fact of the matter is that there are in Britain some 25,000 human clones walking around all the time, perfectly healthily – they’re called identical twins. But somehow cloning is seen to be a huge moral threat.

I don’t think that it is, and I think it has clouded some real issues behind embryology which are worthy of much more serious consideration. I don’t know of anybody who is remotely interested in cloning human beings. There may be a few whacky and misguided individuals who want to clone themselves, but if I chose to clone myself today, in the middle of June, the baby that was me would be born in nine months’ time. So it would have been born at least more than 60 years after I was born in a different uterus, in a different environment, with different breast milk, different hormonal influences, in a totally different manner. The notion that somehow our genes make us what we are is of course nonsense! We are as much the product of our environment and how our environment impinges on those genes as the genetic makeup, and so we would be far more dissimilar, if each of us were cloned today, than any identical twin, or even non-identical twin that we had that was born at the same time. It’s worth thinking about that, and perhaps considering exactly what the moral problem is. I think there are problems, but they’re not particularly serious ones.

Let’s look at today’s news. What we’ve been told today by the various newspapers that I scanned very quickly is that sperm and egg cells have been grown from stem cells. It’s not true. They haven’t. What they’ve grown are embryoid bodies, which look vaguely like stem cells, may have their properties, but it is as unclear whether they are stem cells, and if they are stem cells, whether they have any potential for growing into these highly differentiated germ cells. It has been suggested that these might make grafts for cancer patients, when it turns out that perhaps the greatest risk of a stem cell graft is causing a cancer. One of the major concerns about stem cells is that once they’re re-implanted in the body, they may in fact act as rogue cells.

It is said in one of the newspapers today, one of the broadsheets, that it will be helpful for cloning humans who don’t happen to have a partner, and that this also might be a good treatment for homosexual couples. That’s in The Times. Once again there’s a deliberate attempt to slur some interesting science, which has been seen in a greatly inflated way. People always rush to see the human embryology conference which is run in Europe every year. It produces these stories, and it’s always a good way of having yet another story about how to beat the female menopause. I am not quite sure how you would, but presumably you could make new eggs, in some curious way repopulate the human female ovary, and rejuvenate women. It is a laughable idea.

The problem is that we give, again and again, credibility to people who actually don’t have scientific credibility. I can say this without fear of litigation: Panayiotis Zavos is, to my mind, a fraud. If you look at his scientific record, he doesn’t have a single peer review publication in the field of cloning which holds up any evidence that he could do what he claims to have done over the last five years. The same applies to Antinori, but the effect of Antinori in Italy was devastating! You will be aware that the Italian Parliament has now produced legislation which virtually prevents patients getting infertility treatment when they are infertile just by routine IVF in consequence. So the failure of trust which was caused by aberrant rogue scientists was very serious.

I think inherent in all this is the kernel of another problem. One of the problems is that in order to persuade the public that we must do this work; we often go rather too far in promising what we might achieve. This is a real issue for the scientists. I am not entirely convinced that embryonic stem cells will, in my lifetime, and possibly anybody’s lifetime for that matter, be holding quite the promise that we desperately hope they will.

We will certainly gain, and are gaining, amazingly important information about the development of cancer with these cells, and a whole range of other problems which occur in human medicine, but when you look at embryonic stem cells, one of the real issues is that these cells divide so very slowly in culture that you may never get enough populations of the cells to repopulate a damaged organ. For example, if you want to repopulate the heart after a coronary incident, it’s calculated you’d need about ten million cells injected into the heart, in a human heart. You would never generate that very easily in culture. What we’re trying to do in my lab at the moment is generate dozens of cells, and it has taken one of my post-docs weeks and weeks to develop just a handful of stem cells from a recognised stem line.

Another problem is that there is selective evolutionary pressure in culture for the faster growing cells to survive. That’s really very interesting. It has never been thought about before, but what will tend to happen in any culture is that the cells which grow faster will succeed. The slower growing cells will tend to be depopulated because of the pressure on them environmentally. But the faster cells may be abnormal cells, not the ones which will give rise to a good tissue. And another selective pressure is that against programme cell death. All human cells are programmed to die when they become abnormal, so what may happen here is that you end up with cells which should have died but haven’t died and therefore may have all sorts of strange genetics. Human embryos also often have abnormal chromosomes, and trying to push these cells artificially may increase the abnormalities in the chromosomes. If you use cells which have been autologously derived, that is to say, from the same person, if you’re using their bone marrow and you’re treating a disease which may have some genetic component, what you are doing is replacing those cells with cells which already have the marker for that genetic disease in them. So it isn’t necessarily quite such a cut and dried process.

Two big problems which science has been unable to deal with at the moment is the risk of cells which have been derived and differentiated into a desired tissue, like nerve tissue, then failing to differentiate or de-differentiating and becoming other cells after they’ve been transferred, perhaps with terrible consequences. If you’re transferring ten million cells into a person, how can you tell that amongst those cells there isn’t one rogue cell that might carry the risk of something which could be akin to a cancer? We know, for example, that stem cells transplanted in animals do cause cancers.

Most of that information doesn’t come out in the public domain. It should do. Let me make it absolutely clear: I believe that stem cell research and embryonic stem cell research is highly important, extremely valuable, and should be conducted, and I believe is totally ethical, because it helps us to understand all sorts of crippling and life-threatening diseases. That seems to me to be morally preferable than throwing away embryos that you can’t use in an IVF programme. But don’t let’s forget that there are negative aspects to every science, and that needs to be admitted. If it’s not admitted, I think we may end up with very real problems.

One of the biggest problems too are single issue pressure groups – the Animal Liberation Front is a very good example, who I think do a huge disservice to much of science, because they do not allow humane research to continue, and consequently, we are held up. It has taken me a year and a quarter to get a licence to inject a completely harmless gene sequence, with a completely harmless virus attached, into six pigs’ testicles. The pigs will suffer no pain, beyond the momentary prick. There’s not the slightest evidence that this virus is pathogenic or that the genes that we’re looking at are in any way harmful to the pig or its offspring, but it has taken 14 months to get approval to study six pigs’ sperm. That seems to me to be extraordinary, and it is in part the response to the exaggerated response, in my view, to what is a growing problem in human biology and human medicine.

When you look at public attitudes, it is extraordinary that 80% of the population would find it quite acceptable to give drugs which are experimental to humans, but only 63% of the population would allow these experiments on bacteria. There is something seriously wrong with our society if we are more concerned about bacteria and rabbits than about dying humans and the potential for using volunteers who have given informed consent. That seems to me to be an extraordinary issue which we have not failed to recognise. It is true that there is growing recognition that where, for example, children are at risk of dying, particularly when there’s no pain involved with the humane experiment, then people will allow, certainly at least in rodents, a great deal of experimentation, but are more concerned about monkeys, and more concerned, I think quite properly, where there might be pain or suffering to the animal concerned. But the public reaction to research is not entirely a rational one. It would be worth perhaps considering through a parliamentary bill placing on every drug sold in every chemist the words, as is on the cigarette packet, this may endanger or kill you, – “These drugs were produced as a result of animal research to prove their safety and efficacy”, because that in fact is the truth for all drugs which are sold.

Let me come to another issue in science; the issue of science being seen, by both scientists and non-scientists, as certainty. A headline in The Sun newspaper a few years ago said: the NHS misses one in five cervical cancers. I don’t know where they got the evidence for that, but apparently 14 women died in a smear scandal. I think it turned out that many of those women hadn’t actually died of cervical cancer, but there we are. The point that the editor was making was that if you’re a solicitor or a bricklayer on the top floor of the Clapham omnibus, you can tell the difference between a cancer smear and a normal smear, so why couldn’t the doctors? The notion is that everything in medicine and science is in black and white, and it clearly isn’t. It’s partly our fault, because we have promoted science, to some extent, as if it is certainty, and it is very far from being certain.

Certainty isn’t only an issue in science; it’s also an issue in religion. I recently went to the Grand Canyon in Arizona, where I met Tom, a delightful man. Tom is a fundamentalist Christian, and he believes that the Grand Canyon was formed by Noah’s flood, that there’s no other explanation, that in fact the world started 6,002 years ago, that every word in the Bible is literally true, and as far as he’s concerned, the words in the Bible are so completely true that we cannot argue about them, because if we did, we would undermine the value of the New Testament. I am not quite sure how he arrives at that view, particularly as, as far as I’m aware, Tom doesn’t speak classical Hebrew, or indeed for that matter Greek, so presumably he’s only read the Old Testament in the English translation which has been supplied to him and which many scholars will argue has a particular slant on the text. Be that as it may, he is certain, and it seems to me that certainty and uncertainty are in common to both religious and scientific groups, and we are, all of us, uncertain, and I think we should remember our uncertainty. In my view, when science and religion become certain, they are probably equally dangerous.

Another visit I recently made was to Isfahan in Iran, and saw the Ishura festival. 40,000 were in the second biggest square in the world, after Tiananmen Square, and were flagellating themselves with iron chains. It was a pretty impressive sight. I’m not making any remarks about Islam here. I merely suggest that to us it is so incomprehensible that people could want to draw their own blood in this way and that we see this as another form of fundamentalism. I’m not sure that it really is. It was very interesting talking to the Ayatollah, admittedly through a translator, afterwards, who when I asked him, rather cheekily, why he though Shia was the true faith, and I had my heart in my mouth when I did that, he said, “Well, it’s obvious, of course it’s the true faith.” He knew, by the way, I was a Jew. He said, “It must be the true faith because of course it has come after Judaism and Christianity.” It’s an impeccable argument!

Lee Silver, the molecular biologist, shows equal certainty in Princeton University. He’s a good molecular biologist, but I do wish he would have a little bit more commonsense. He’s proposed that we should try using gene technology to enhance human cognitive function. “Why not,” he said, “modify humans so that they have genes for ultraviolet and infrared vision, like spiders and snakes? It would make us very good spies.” Magnetic detection would obviate the need for men to ask the way for directions, and solar guidance would help women probably as well when they’re wondering, what’s going on behind their backs. And no doubt many of us, not me I must say, would like to have improved olfaction, using dog genes. Well, it seems to me to be a very poor recognition of the responsibility of a scientist dabbling in genetics to posit this nonsense.

On the other hand, we have my really good friend, Richard Dawkins, and he’s such a good friend that I feel slightly embarrassed about taking this quote of his, but it’s typical of much of what Richard sometimes writes. He is a brilliant writer, but I think sometimes he should think a little bit about what he says. Of 9/11 he said, “It came from religion. Religion is also of course the underlying source of divisiveness in the Middle East which motivated this deadly weapon in the first place. That is not my concern here. My concern here is with the weapon itself. To fill the world with the religion or religions of the Abrahamic kind is like littering the streets with loaded guns. Do not be surprised if they are used.”

I suspect that the great majority of people in the UK, with a few exceptions, would regard themselves, at least in some way, as coming from a religion which was of the Abrahamic faith, or living in a society whose structure has been founded and based on one of the Abrahamic faiths. Indeed, in my view, our whole morality, the Church of England, which I believe is a very fine organisation, is a very good example of the civilising influence of how religion might be used more often morally. It seems to me that it is foolish for a scientist to rail against the Abrahamic religions in this sort of way. In Europe, whether we like it or not, a great number of people still have this notion – about two-thirds or three-quarters of us – of some influence which we cannot explain, a spiritual being, possibly a god, and many of us feel that we need moments of prayer, and define ourselves as, broadly speaking, religious, even though something like only about 13% of us go to church, extrinsically religious as opposed to this intrinsic religion, and I think there is a difference here. I think, surprisingly, a very large number of humans are intrinsically religious, using the psychologists’ definition of a religion, which comes from an innate spirituality.

It is therefore unwise for scientists to pour scorn on that. It seems to me to be a very good way of breaking trust, not to understand those feelings. James Watson, the Nobel Prize winner, who of course achieved his Nobel Prize as a result of the work in Cambridge, said of germline therapy, which most of us would regard as being one of the most dangerous developments in modern biology, “It will be much more successful than somatic therapy. The biggest ethical problem is not using our knowledge.” This is something he said in 1997, but he has repeated similar views up to the present day. In my view, that’s quite shocking. I think we have to recognise that whilst science itself does not have a moral dimension, the technology which is derived from science certainly does, and scientists need to have a much clearer and better stated idea of where the ethical issues are. Thank god for Eric Lander of the Genome Project, speaking from Washington, saying, “There will come a time when we can do such things, such as germline therapy, and it is not too soon to ask whether we should.”

What conclusions can I draw? There are some serious issues which are quite disparate, which are related to the pubic distrust. Some of them are commercial. Some of them are failure to understand ethics. Some of them are failures of communication. Sometimes they’re whipped up by the media. Sometimes it’s the fault of the politicians. Sometimes it is the insensitivity of the scientists, and not understanding the nature of science. The problem is that in the modern university, science is still taught in a competitive environment, and one of the reasons why too few women stay in science is because they don’t like the competitive environment. In my view, one of the best things that could happen to science would be to encourage more women into the laboratory, and to make sure they stay there, because I think they are the greatest civilising influence. There is little teaching of communication skills amongst young scientists, so we read White Papers which are unintelligible. This is a common problem. It is true not only amongst scientists but also, dare I say it, social scientists, who ought to know better. I’ve been re-reading a lot of social science papers this weekend for a book I’m writing, and frankly, some of the papers I just had to give up because, try as I might, I couldn’t understand what the social scientist was saying, and after all, we speak, nominally, the same language.

There are very few universities, if any, that run a course for all their undergraduate scientists on ethics. As far as I’m aware, this only happens in medical schools, but in my view, ethics should be central to the teaching of science at university, and there should be more courses more formally available.

There’s no formal teaching about commercial interests. Of course we need to have commercial interests, of course it’s nonsense to suggest we shouldn’t be developing intellectual property, of course universities must profit to some extent from what they’re doing, but it is worrying that the Government is increasingly driving universities down this commercial route, with these conflicts of interest, and I think that that is cause for consideration. I don’t think David Sainsbury, our very respected science minister, fully understands that there is a negative downside to this which we should be a little bit more aware of and somewhat sensitive to. We’ve seen it with GM crops.

The philosophy of science is hardly taught at all. We don’t teach science about uncertainty; we don’t teach what is the nature of science, except unless it’s a specific course, at Imperial College for example, but this is certainly not taught in general to scientists.

Above all, we have very little understanding of engagement. In the Wreath Lectures, Sir Alex Broers, who is an outstanding engineer, talked about engagement, but I didn’t get the feeling that he understood really what engagement was. Engagement must mean listening to the concerns of the public, and more than listening, responding to them. If there are things that they feel that the scientists are not doing, or where they feel the scientists should be recognising there is public ownership of the problem, then I think we have to engage with that and we have to recognise that. Of course in some cases, it may hold up science, but that must be for the public good. So communication is only the beginning of the problem. We need more public dialogue and more involvement with scientists. Scientists, people like PhD students in my laboratory, should be out in the schools talking about what they do with enthusiasm to young children. We should be demonstrating much more sensitivity and ethics. We should reinforce the fact that everybody in society owns the science that we produce. We should understand its nature. We should beware of exaggeration, and certainty, and over-confidence. We need to retain a degree of independence from politicians. One of the problems with MMR, by the way, was the fact that the scientists promoting the measles vaccine were seen as government scientists; in my view, that was a grave error. We need to be giving much clearer information to the media. I don’t know quite how we deal with the print media, but I suspect that they’re becoming increasingly irrelevant as they become more and more, as Andrew Marr says, like supermarkets.

And we need to have more activity at university, at all levels. Above all, the real trick must be in the school. To my mind, where the real problem must be tackled is with school children. We’re doing it with primary school. We’re not so good between eight onwards, to 14. It seems to me, particularly between 11 and 14, we lose a lot of young people. When I go round schools and talk to 11 year olds, I am staggered by the number of 11 year olds who’ve told me they thought science was boring. One thing that it never is, is boring, and if it is boring, it is because we’re not doing it in a way which engages the children, and we need to assess that much more vigorously. Maybe we might even have to, on occasion, ignore the Health and Safety Executive!

To conclude, Pieter Brueghel the Elder, in 1553, produced a wood cut of the alchemist in his laboratory. The alchemist was poring over his tome, in Flemish, a pun on the word alchemist. In the centre of the picture is presumably his wife. She hasn’t had a grant recently from the Medical Research Council! The two people looking like PhD students are trying to transmute base metals into gold – or maybe trying to find the elixir of life. But the real story here, because so many of these prints tell a story, is the children, who are seen at the back in the laboratory running amok, one with a coal scuttle on his head. Brueghel is telling something very important here. Alchemist is, as I say, a pun. Alchemist means alchemist, but alchemist also means “all has miscarried”or “all is lost” in Flemish. Through the window is the medieval device of the future. There are three children, one with the coal scuttle still on his head, being admitted to le hopital, not the hospital, the poor house. What has happened? The alchemist has subsumed everything. He has devoted his entire attention to technology, and he has forgotten the real reason why he is doing it – for the health and welfare of the next generation.

© Professor Lord Winston, Gresham Special Lecture, 20 June 2005

This event was on Mon, 20 Jun 2005

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham College plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login