Superhumans? - Interfering with nature

Share

- Details

- Transcript

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

Should we engineer the human genome? The ethics of stem cell research. Will humans be superseded? The Christian Natural Law tradition in morals.

Download Transcript

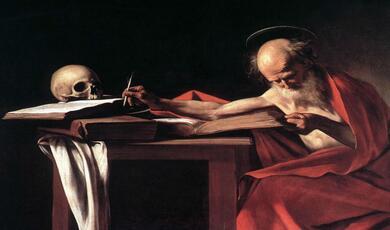

SUPERHUMANS? - INTERFERING WITH NATURE

Professor Keith Ward

The year 1953 marked a decisive turning point in human history. In that year the structure of DNA, the mechanism of human heredity, was discovered. Since then the complete human genome, the sequence of genes that determine major human bodily and mental characteristics, has been decoded. In this century, humans for the first time have the ability to identify and change the genes that make us human, that decide our characters and abilities as humans. In a completely unprecedented way, we can begin to remake human nature, and shape it in accordance with our wishes.

This raises a whole series of new moral questions, that could never have arisen in this way in past history. If we have the ability to change human nature, should we do so, and in what way? There are already societies in existence which are looking forward to the creation of trans-humans, beings so much more intelligent, healthy and strong than us that they will be like gods, with vast power, knowledge, and perhaps even immortality.

This sounds like science fiction, but most geneticists accept that we may be able to eliminate some major heritable diseases, like Downs' Syndrome, by replacing the genes that cause such conditions - this is sometimes known as negative genetic engineering. We should also be able to identify genes for such things as blonde hair, blue eyes, gender and intelligence. We may then be able to insert such genes into a sequence of genes, a genome, and produce healthy and intelligent children, of desired sex and skin-colour, to order. So it is not completely fantastic to suppose that we may be able one day to engineer a genome for a trans-human race, one that is as far superior to present humans as humans now are to chimpanzees. This is the future to which the Trans-Human Society looks forward.

At the other end of the moral spectrum are those who say that we should not tamper with the human genome at all. We should not, they say, 'play God'. Research onto human genetic material is morally forbidden, because it involves experimentation on living human material. We may be able to remedy some gross genetic defects, but we should not try to change human nature itself, which is as it is meant to be.

These are perplexing moral issues, which there is no precedent for resolving. Where do the religions stand on such issues? Is genetic engineering morally permissible? And should we look forward to the replacement of the human race by a superior, artificially engineered, species?

NATURAL INCLINATIONS. I have said that there is no precedent for resolving these issues. But that is not strictly true. For there is a long Christian tradition of moral thinking, partly drawn from ancient Stoic philosophy but developed in the late Middle Ages by theologians like Thomas Aquinas, that makes a close connection between morality and human nature. For this tradition, knowledge of morality is not dependent on revelation. Its main precepts are knowable by reason, reflecting on the natural inclinations of human nature.

There is thus a 'natural', non-revealed, knowledge of right and wrong.

Aquinas' version of natural law also holds that the moral goods that are 'natural' are those 'towards which man has a natural tendency' or natural inclination (naturalem inclinationem). Agreeing with Aristotle, he thinks that all things have a natural inclination to their proper end. That is part of the natural order of things, as created by God. And God 'commands us to respect the natural order and forbids us to disturb it'. So we should always respect, and never frustrate, our natural inclinations. and the order of nature.

Natural inclinations are not necessarily things that we find to be rationally desirable. I may have a natural inclination to do undesirable things. In fact I probably do, if I have a natural tendency to kill my rivals. I may also desire to do things for which there is no natural inclination. Again, many people do, for some desire to change their bodies by plastic surgery, even to grow facial whiskers like cats. There is no natural tendency to do that. I may have an instinctive, or natural, tendency to run from wild animals. But perhaps I should counteract that tendency, to become more courageous or in order to make friends with animals.

As G. E. Moore argued, one cannot assume that a way in which I naturally tend to behave is desirable, either for myself or for others. Humans tend to rape, kill and lie, and such behaviour is very undesirable. The view that natural inclinations are, as such, good would be widely denied by evolutionary biologists. We now know, though we have only really known since the structure of DNA was discovered, that there are behavioural tendencies in human beings that are laid down in the coding of transmitted DNA.

It is our DNA that carries a code for building proteins that will in turn construct bodies with specific physical characteristics and tendencies to behave in certain 'instinctive' ways. These are our natural inclinations. In every generation DNA is subject to mutations or chemical changes - humans generate about 100 mutations per generation. Some of these are harmful, and so are anything but good. Some of them give rise to natural inclinations that may or may not be harmful. Most of the harmful inclinations are eliminated by natural selection, but some get through. So the tendency to hate foreigners, and for men to subjugate and rape women, are tendencies that have proved quite conducive to human survival as a species. But they could hardly be called good, or in accord with the purposes of God. It is, of course, true that the things we naturally tend to do have been conducive to survival over thousands or millions of years. Otherwise we would not have survived. And it seems likely that behavioural tendencies conducive to survival would generally have come to be thought desirable, and to be associated with pleasure. But these are not necessary or inviolable connections. I may have a tendency to take intoxicating substances, which give pleasure. Such a tendency may be genetically ingrained, and it may have survived in the genome simply because its harmfulness has not been bad enough to wipe the human species out. Nevertheless, intoxicating substances may be very bad for me, and kill me in the end. From an evolutionary point of view, this would not matter very much, since in the end I would be beyond reproductive age in any case, so the harm done to me would not cause any decrease in fecundity. It might even increase my fecundity when I am young, though it will kill me as soon as I am past child-bearing age. So this natural tendency will be good for reproductive success, but bad for me personally. If I can take rational control of my behaviour, I might well desire to live longer and reproduce less, in which case my rational desires will conflict with my natural inclinations.

To take another case, humans may be naturally aggressive, for that has had an evolutionary advantage in the past. But now it is counter-productive, and may lead to the extermination of the human race. What is genetically programmed, according to evolutionary biologists, is what was good for the survival of my genes in the far past, or what at least was not counter-productive, thousands or millions of years ago. That may now be very bad for survival, and so should be rationally opposed.

The evolutionary theorist Richard Dawkins speaks of 'attaining freedom from the tyranny of the genes'. On most evolutionary accounts, my inherited tendencies need to be rationally controlled or even opposed, for as Tennyson wrote, 'Nature is red in tooth and claw'. T. H. Huxley, in a famous essay on evolution and ethics, held that evolutionary success depends on increasing lust and aggression and on the ruthless extermination of rivals. The behaviour this naturally gives rise to is a strong sense of kin-group, limited altruism, coupled with extreme hostility to all competing groups. In the modern world we may need to counter these natural tendencies, extend human sympathy more widely, and encourage rational control of instinctive behaviour. Reason can often find itself in opposition to natural tendencies or inclinations. An evolutionary account of human behaviour shows how this can be so - because what proved advantageous in the far past may be fatal now.

THE EVOLUTIONARY WORLD VIEW. When Aquinas wrote, he did not have an evolutionary worldview. He was assuming an Aristotelian worldview, according to which all things have final causes, end-states towards which they strive by an inherent purposiveness. Modern science ejects all such final causes from the physical world, or at least refuses to consider them. Physicists speak of initial states and laws governing physical change. But they do not speak of states for the sake of which physical entities exist, and towards which they strive.

A natural inclination, for Aristotle, is the movement of a thing towards its final cause. That final cause is also usually the formal cause, the true definition of a thing. The idea is that things move towards the proper actualisation of their essential natures. But for modern physics, there are no essential natures, and no purposive movement towards them. It is in biology that relics of Aristotelian final and formal causality may still be found. We can think of an acorn as tending towards its final cause, an oak tree. We can think of a fertilised egg as tending towards the goal of producing a new animal. Taking food has the purpose of maintaining a body in existence.

But Darwinian evolution, even more than modern physics, places a large question mark against such teleological pictures of biological nature. Suppose we ask the question, 'Is there a purpose towards which the evolutionary process moves?' Among biologists this is a highly disputed issue. Biologists like Stephen J. Gould held that human life is not the purpose of evolution. Humans are just what happened not to be exterminated by early environments - and they may exterminate themselves very soon, leaving ants or beetles to inherit the earth. Others, however, like Simon Conway Morris, argue that even from a purely physical point of view a tendency can be seen in evolution, towards the development of conscious and intelligent life. Anyone who believes in a creator God is almost bound to believe that God created the universe for a purpose, and that therefore the evolutionary process must be purposive in some sense, must tend towards the goal God has set for it. For Christians and other believers in a creator God, that goal at least partly consists in the existence of finite beings capable of a conscious loving relationship with one another and with the creator. The goal is the existence of persons capable of conscious relationship with God, and the physical processes of evolution must be consistent with that.

Despite the fact that evolution is widely seen as undirected and largely random, it would be widely agreed that the process at least looks as though it leads to the emergence of more complex organisms and to intelligent life. It looks goal-directed, and so the Christian is on strong ground in thinking that it is goal-directed. Nevertheless virtually all biologists agree that the process of evolution, even if it is goal-directed in general, is one that operates by random mutation and natural selection.

Mutations are random in that not all of them are conductive to improvements in the efficiency or well-being of organisms. Indeed the majority of mutations are harmful to organisms, leading to their extinction, and many more mutations have no tendency to organic 'improvement'. Only a very few mutations are beneficial, though that tiny minority that do give a survival-advantage naturally tend to replicate and flourish exponentially.

In such a process, one can speak of a natural tendency only with some care. The process as a whole may have a tendency to produce intelligent life, but in its particular details the tendency looks more like a trial-and-error process in which there are vastly many more errors than successes. Even when there are beneficial mutations, they need to be selected by the environment. Such 'natural' selection is actually a process of killing off the less well adapted rather than a matter of positive and prudential encouragement. God may have set up the process for a good end, but it is hard to think that the extermination of species, a natural and probably inevitable part of the evolutionary process, is something positively willed as good in itself, by God. So the evolutionary process, as seen by most biologists, causes vast amounts of harm, and seems wasteful and ruthless. Most individual organisms are doomed to extinction; in fact all are doomed to die.

Death is not the result of some primordial human sin. It was an essential feature of organic existence millions of years before humans came into existence. We might well say that all organisms have a natural tendency to die. Death, as seen by evolutionary biologists, is certainly natural, and not any sort of corruption of organic existence. Anyone who accepts these evolutionary beliefs - and that is most competent evolutionary biologists - must say that, if there is purpose in the process, it is hardly a purpose which could not be improved upon, or which should not be improved if one had the ability to do so.

The biological world, as seen by evolutionary biologists, is most certainly not in order as it is, to be respectfully left alone as the ordinance of the creator. To put it bluntly, nature does not always act for the best. It naturally produces a majority of harmful mutations. So there seems little reason to say that there is any sort of moral obligation to leave natural processes alone. If one can identify some good or beneficial effects of mutation, they should be chosen and protected, even if that means interfering with natural processes of mutation and selection. For the natural processes produce much harm, which rational interference might be able to prevent. They work by trial and error, and by ruthless methods of extinction (like the extinction event that wiped out the dinosaurs 65 million years ago, which enabled humans to evolve). Of course, this is just why Charles Darwin came to doubt the kindly providence (though not the existence) of God.

Natural processes do not seem to be perfectly designed by a benevolent intelligence. I can see why many Christians find Darwinian evolution a threat to faith. Now a Darwinian account of evolution, in terms of random mutation and natural selection, may be misguided in some way. But suppose we accept it, as the best established theory there is for explaining the development of intelligent life, what are the consequences for Christian belief? A Christian has to believe that God is a benevolent intelligence who designs and creates the cosmos. It seems to follow that the general process of evolution must be intelligent, efficiently ordered to produce its specific effects, goal-directed and benevolent in intention.

It seems to me that we could defend such a belief if the general structure of physical laws which make this cosmos possible entail that the evolutionary process must function in the way it does - by mutation and weeding out non-adaptive mutations. The process is based on supremely elegant laws, and perhaps it can be guaranteed to produce intelligent life, which can share in the life of supreme goodness.

In some such way, belief in creation can be defended. But not every part of the natural process will be desirable. Although the process as a whole is designed to effect a good end, many of its particular parts cause great harm. In that case, it would seem irresponsible to think that all natural processes should be left as they are, even if we become able to reduce the number of harmful mutations, or to mitigate some of the more ruthless aspects of the struggle for existence.

In the practice of medicine, we have begun to do this. Humans sometimes keep the less healthy members of the species alive, often at great expense. And there is hope of eliminating some of the most harmful genetic mutations (like that for Downs' syndrome), by either chemical or surgical intervention. Clearly, we do not believe that natural processes are good per se. They are good only when they issue in rationally desirable outcomes. What is intended by God must be discernible in the facts of human behaviour. If God has a purpose in evolution, we should be able to discern, at least in a general way, what that purpose is by seeing what valued states natural processes tend to produce.

Looking at human nature from an evolutionary point of view, it is plausible to say that the purpose of the process is the production of conscious, intelligent, morally responsible and spiritually aware forms of life. It follows that Christian moral obligation will be to help in realising that purpose, and to refrain from frustrating it. That is a sort of 'natural law' morality - seeing what the distinctive nature of human life is, seeing how that can be a divinely ordained purpose, and consequently resolving to act in accordance with the purpose of the natural process, to act in accordance with nature.

However, saying this in a Darwinian context is very different from saying it in an Aristotelian context. An Aristotelian view sees human nature as a matter of the striving of all material beings to realise their proper Form or nature. If we can identify this Form, we will know what a human being 'ought' to be, what it properly, in its most mature form, is. And if we see how organisms tend to behave, we will see what the proper end of their activity is. All things naturally tend to realise their proper natures.

There is a sense in which Christians are bound to be sympathetic to this idea. God must have an idea of what God wants humans to be. If we can identify that idea, we will know how humans should act to realise it. For Christians, human existence is a striving to realise an ideal that exists in the mind of God. In that sense, it is true that we should strive to realise our proper natures. We should seek to become what God wants us to be, to conform to the image of humanity in the mind of God.

But from an evolutionary view, the process by which humans come to exist is not one in which each thing is striving to become what it ought to be. It is one in which there is a huge amount of trial-and-error, and the elimination of many organisms because of their lack of adaptation with the environment. The process does seem to be well constructed to produce intelligent life-forms sooner or later. But it is not one whose details command our moral respect, or demand our moral submission to all its natural tendencies or inclinations. For an Aristotelian view, it makes sense to say that we should act in accordance with nature, in the sense that our natural inclinations will show us what we ought to be (they are our proper strivings leading towards our essential nature). But for an evolutionary view, acting in accordance with nature will have to be interpreted as helping to realise the general purpose of the evolutionary process as a whole. Not all our natural inclinations will show us what that is. For some natural inclinations will be remnants of ancient behavioural tendencies that may now be harmful, and others will simply have failed to exterminate us so far, since they have not been eliminated by natural selection, though they have no positive function.

Our natural inclinations will no longer show us what we ought to be or do. Rather, we will have to discriminate between genetically programmed tendencies that are conducive to the general purpose of enabling intelligent life to flourish, and others that are inefficient in doing so, or that even frustrate the possibility of doing so.

Reflection on distinctive human capacities is a guide to what the divine purpose in evolution may be. But having decided on that, we then have to judge genetically programmed tendencies on their success in helping to achieve such a purpose. Many of the ways in which some organisms act will ensure their extinction (most species becomes extinct). And even if they thrive, some organisms are intrinsically harmful to other organisms (cancer cells, for example). This blocks any move from seeing how things naturally behave to saying that it is good that they behave in that way. It looks as if we have to identify intrinsically good states first, and then ask whether natural processes are apt to achieve them. It is unsatisfactory to look at how things naturally behave in order to see what states are good.

Aquinas confines his remarks about natural law to very general principles. When he considers natural inclinations, he outlines three main types of natural inclination - one shared with all substances, namely, the appetite to self-preservation. The second is what humans share with animals - sexual intercourse and the bringing up of the young. The third is inclinations of beings of a rational nature - including knowledge of God and what relates to living in society (friendship and so on). Natural law covers 'everything to which man is set by his very nature' (94, 3). In an evolutionary worldview, we do not have to reject this principle. Human nature is purposively intended by God, and the inclinations Aquinas picks out - to survive, procreate, know and appreciate beauty and truth, and share friendship and love with others - are inclinations that seem necessary to realising the divine purpose.

The belief that it is objectively wrong to frustrate these natural inclinations is an important safeguard against the view that human rights are simply conventions of governments or societies. Whatever the positive laws of particular countries may be, it is always and everywhere wrong to frustrate the ability of any human being to survivie, found a family, and grow in knowledge and freedom. The doctrine of natural law is a vital foundation of belief in fundamental human rights. Natural law can, at least in its general outlines, be known by reason, and it is founded on the eternal will and purpose of God for human lives. But we have to say, more clearly than Aquinas did, that nature itself has no purposes, and not all her tendencies are good. God has purposes, to be worked out in and through nature.

They can indeed by discerned by reflection on nature, but only by discriminating what tends to the flourishing of personal life from what tends to frustrate such flourishing. An inspection of natural processes themselves will not enable such a discrimination to be made.

Someone who did not believe in God would be very unlikely to take a purposive view of nature, either in an Aristotelian or a Christian sense. They could still discern those capacities that are distinctive of human nature, and would be likely to put value on the mental and moral capacities of human beings. But they would be unlikely to regard physical processes as carrying moral value in themselves, and so would not be likely to think that there are universal tendencies of nature that are as such to be given moral value. They are even less likely to think that such tendencies give rise to absolute prohibitions on interfering with or modifying such tendencies. To that extent a truly universal moral sense might exist, but would regard any reference to natural inclinations to be at best a general guide to the sorts of actions seen to be right and wrong.

Theists, I have suggested, are bound to interpret nature in a purposive sense. But if strongly influenced by evolutionary theory, in a broadly Darwinian sense, they would not regard physical processes as of value in other than an instrumental sense. Such processes and tendencies would be good only to the extent that they subserve the purpose of enabling personal life to flourish. It follows that it is not as such objectively wrong to frustrate some alleged 'purpose of nature'. It might be morally right to frustrate it if it diminishes a truly human good.

It seems as if, from the perspective of modern biology, we can no longer speak of an obligation not to frustrate the purposes of nature. If it is not harmful to organisms, genetic engineering, whether by the use of drugs or of the manipulation of genetic material, can even be morally obligatory. Major heritable diseases could be eliminated and human health much improved by genetic engineering, and the main moral criterion will be whether such engineering is conducive to the human flourishing of the individual (or the potential individual) concerned.

TRANSHUMANS AND THE SOUL. More hesitation may be felt about proposals to improve on humanity, and maybe to breed a species of super-humans. From a traditional Christian point of view, are humans not made in the image of God, and so should they not be preserved as they are? There may be much debate about what the image of God actually is. Many early Christian theologians took it to be saying that humans have knowledge and freedom and creative power, as God does. But in that case it would seem that the more knowledge and power a finite creature had, the more it would reflect the divine image. Is it not reasonable to think that it is God's will that we should grow in knowledge, intellectual ability and moral freedom? If we can find genes that will increase such abilities, taking them beyond present human capacities, that would then seem to be in accordance with God's will. After all, many Christians think that Jesus had super-human miraculous knowledge and powers, but he was still truly human. So there does not seem to be a religious barrier to improving the human species in its intellectual and moral capacities, if we can. Christians have also traditionally believed in the existence of super-human species like angels, so there seems to be no bar in principle to creating super-human species, perhaps like some form of artificial intelligence, if the time comes when we can do so. In such a situation, we would have to be careful to accord such beings the same sorts of rights that morally free human beings have. But I see no reason why humans should think of themselves as the highest forms of created personal life. God loves all creatures, and the human situation may be a relatively humble one in the cosmic scheme of things. That would not lessen human responsibility at all, and might even give it a greater importance in the process of cosmic evolution. Humans may be able to become part-directors of their own future evolution beyond humanity.

One traditional argument against this is that the physical bodies we actually have are an integral part of what we are, and they should not be treated as mere instruments, that we can change or discard just as we wish. God has created us as the body-soul unities that we are, and we are not morally free to change our bodies or our characters by artificial manipulation.

Such an objection is based on the view, which is certainly a traditional Christian one, that human bodies must be seen as parts of one integral and unitary personal reality, and are not disposable bits of mechanism. Despite some popular beliefs to the contrary, the traditional Catholic view of human persons is that they are physical bodies, animals, that possess emergent properties of consciousness and volition. To speak of a 'soul' is to speak of the capacities of a type of physical body, capacities of a type of animal capable of abstract thought and responsible action. Souls cannot properly exist without bodies - a view Aquinas espoused.

The complication here is that the soul is often also spoken of by Aquinas as though it is a non-physical agent of thought, action, sensation and perception. Some form of embodiment may be essential to it, in order to provide information, and the possibility of communication and action. But perhaps the same soul could be embodied in different forms. Anyone who believes in rebirth must believe this.

Catholics, who do not share belief in rebirth, do nevertheless seem to be committed to the existence of souls, both in Purgatory and in Heaven, that have consciousness and experience, but do not have physical bodies. Moreover, whatever the resurrection body is, it is certainly not temporally or physically continuous with this physical body, and it may be significantly different in some respects (it will not be corruptible, and will not have exactly the same physical properties). Aquinas said that disembodied souls may exist 'improperly and unnaturally', by the grace of God, and will not fully be persons again until the resurrection. But it is obvious that a resurrected body will not be constituted of the same physical stuff as present bodies (it is said to be spiritual, not physical). The present physical universe will come to an end, and there will be 'a new heaven and earth'. What that means is that the physical stuff of this specific universe is not essential to the nature and continuous existence of persons, even though something analogous to this body must exist.

What is at stake in this discussion is whether human consciousness is an emergent property of a physical object - and so ceases to function or exist without that object. Or whether human consciousness, though it does originate within a physical body, and does require some form of embodiment, is nevertheless dissociable from its original body, and is capable of existence in other forms. Is the soul adjectival to the body, or is this body just one form in which this soul may exist? Aquinas tries to straddle both sides of this divide by speaking of the soul as a 'subsistent form', something whose function it is to give a body specific capacities, but which is capable of existing, though not of functioning in its full and proper way, without that body.

It is this point that many biologists and psychologists have great difficulty understanding. Many of them can see intelligence as an emergent property of a physical organism. But they are resolutely opposed to any form of vitalism, of a view that the body is actually regulated in its physical organisation and structure by a spiritual principle or agency, whether this is called a 'soul' or a 'form'. This may seem a rather recondite philosophical dispute, but actually it shows the importance of views of human nature to morality. Our view of what a person is may make a very important difference to the moral precepts we accept. If we insist on the primary importance of humans as body-soul unities, then the body should not be regarded as simply 'raw material', something 'extrinsic to the person', that can be shaped or dealt with in any way one wishes. The unity of soul and body means that we must respect our bodily structure, since that is part of what we essentially are - 'body and soul are inseperable', and the body intrinsically has moral meaning.

We might contrast this view with some Hindu views that the body is just a garment that we put on or off. For Aquinas, the body is constitutive of what we are, and we would not be the same being without it, without the specific body we have. This is what is intended by the traditional Catholic view that each soul is fitted for a specific body. We might say that each soul is the unique soul of a unique body. From this two things have been said to follow. First, the finality of our bodily tendencies cannot be regarded as purely physical or pre-moral. Our bodily structure and inclinations are morally relevant, and relate directly to the fulfilment of the total human person, body and soul. Second, each person, as created in the image of God and ordered towards participation in the life of God, has intrinsic dignity and inviolability. It may therefore be thought that we are morally obliged not to perform any act that would change or modify our own unique body and character as it has been given to us in our creation. However, I do not think this follows.

Suppose we agree that persons are physical organisms with intellectual or spiritual capacities. These capacities are rooted in a non-physical entity, capable of non-physical existence, but the proper functioning of which is within the specific physical body which is part of its proper being, and which has always to some degree limited and shaped its operation. This is what the philosopher Charles Taliaferro calls 'integrative dualism', and it seems to me to describe the traditional Catholic view rather well. What follows from this account?

Certainly, that human bodies are not mere adjuncts of persons. When they are functioning properly, they should express a personal life. Bodily acts are personal acts. Part of human flourishing is bodily flourishing, and that means due realisation of the capacities and excellences of the body. The most basic moral principle this suggests is that of life and health. The body should not be abused. So while there is nothing wrong with eating for pleasure, the real purpose of eating is to produce a healthy body, and considerations of pleasure should be subordinate to that. The use of drugs and excessive wine or food is morally prohibited, and regular exercise is morally prescribed.

It is not so clear, however, that such prohibitions allow of no exceptions. Excessive drinking is incapable of ordering a life towards God, and it contradicts the good of the person. But does this entail that there are no circumstances in which one may get drunk? Suppose that some madman threatens to shoot your family unless you drink a bottle of whisky. Would it not be right to drink the bottle? Such an act might reasonably be seen as violating the dignity of one's own person. It would hardly be worth formulating a moral principle: 'Never get drunk unless a madman threatens your family unless you do'. It would not undermine the importance of the principle of temperance to accept such hopefully rare and extreme cases. One would simply be saying that preventing the death of many innocent people is more morally important than not getting drunk. The fundamental point would be that moral precepts can, in rare and extreme situations, conflict. When they do, they can be ranked in order of moral importance, and the less important precept can be violated if it is the only way to keep the more important precept. Moral prohibitions can be serious without being absolute. And if one accepts that there are degrees of moral importance, and that precepts can conflict, then it seems reasonable, without benefit of revelation, to think that some prohibitions can sometimes be violated.

So what we have are principles enjoining acts that increase bodily and mental well- being and the highest use of bodily and mental capacities. They are not principles that can never be violated, but there must be very strong moral reasons for violating them. They are, in almost all cases, morally binding. However, it is fairly clear that it is the mental and spiritual capacities that are of primary importance. Often our bodies can frustrate our mental capacities, our abilities to do things, and in that case it is right to try to remove such frustrations, whether that is by the use of drugs or surgery. So if our bodies can be improved to enable our mental capacities to be better expressed, there seems every reason to do so.

From a religious point of view, the goal of human life is not simply to survive or to reproduce. It is to know and love God for ever. The possession of some body is important to us, because we are embodied souls. But our bodies exist primarily to express the capacities of the soul, and for those who believe in the resurrection of the body, those resurrected bodies will be more glorious and incorruptible by far than our present bodies (see 1 Corinthians 15).

In this way, I think a perception of the spiritual destiny of humanity suggests that the physical body does not have morally absolute status, and that the primary spiritual principle, besides the love of God, is the flourishing of personal life rather than the preservation of the present physical order, whatever it may be. The physical order may need to be ordered to the greater flourishing of sentient, intelligent and responsible life, before it fulfils what we might see to be its proper role. Christian revelation helps to define what true human flourishing is. It demands that all bodily activities express love and concern for others, the strengthening of faithful and loyal friendship, and an ordering towards final fulfilment in the knowledge and love of God. It does not demand (or, in its Scriptural sources, even mention) a prohibition on frustrating the purposes of nature. It does require that all physical activities are to be assessed and modified in the light of our spiritual orientations.

Thus our contemporary view of the cosmos as a vast evolutionary process suggests a revised view of natural law. There is a natural sense of right and wrong. It is deepened by the Christian revelation of a transcendent moral purpose in nature. But that must not be confused with alleged 'purposes' in the details of physical processes themselves. As humans come to take full responsibility for their future, they can begin to shape physical processes towards truly spiritual ends. The natural moral law, illumined by revelation, does not say: 'God has made this, do not interfere'. It rather says, 'God has given you responsibility for this; shape it wisely, always bearing in mind the goal of greater understanding, compassion and freedom.' Matters of morality remain matters for human decision. The Christian - and perhaps any religious - dimension is to make us the sort of persons who can make such decisions wisely, compassionately, and with love. Natural Law, in its post-evolutionary form, points towards the future perfection of nature (though it does not guarantee any such thing). It sets the direction in which humans might seek to shape nature. And thus it suggests a way in which one vocation of humans is to be responsible co-creators with God of a physical world that can more truly and fully express spiritual values.

©Professor Keith Ward, Gresham College, 8 February 2007

This event was on Thu, 08 Feb 2007

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login