Are you the Customer or the Product?

Share

- Details

- Transcript

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

It has been said that if you are not paying for a service, then you are the product, not the customer. To what extent is this true for free software, social networking, and other free IT services and products? If we are the product, are we selling ourselves too cheaply? Who is tracking us, and how? How can we retain control?

Download Transcript

18 October 2016

Are You the Customer or the Product?

Professor Martyn Thomas

Introduction

It has been said that if a service is provided free then you are not the customer: you are actually the product that is being sold . This lecture explores the extent to which this is true for Internet companies and considers: the ways in which companies try to maximise the value they can make from us, whether we are getting good value or being harmed, and how much control we can retain or recover. I refer to Facebook, Google and Twitter extensively throughout this lecture because they are so widely used and therefore so important. Much of what I say will apply extensively or in part to very many other websites and online services, whether free or paid for.

We shall start with some numbers.

Facebook and Twitter

In the three months to 30 June 2016, Facebook’s revenue was $6.436 Billion with a profit (income before tax but after spending $1.462 Billion on R&D) of $2.766 Billion . Facebook is worth more than $350 Billion. In the second quarter of 2016, Facebook had 1.71 billion monthly active users , so each user is worth $204 to Facebook investors, and generates $1.62 profit every three months.

In the three months to 30 June 2016, Twitter revenue was $602 million with a loss (income before tax but after spending $178 million on R&D) of $104 million . Twitter is worth more than $12 Billion. In the second quarter of 2016, Twitter had 313 million monthly active users , so each active user is worth $38 to Twitter investors, and costs 33¢ loss every three months. Facebook spent $16B - $19B to buy WhatsApp in 2014 when WhatsApp had 450m active users. Google bought YouTube for $1.6B in 2006, when YouTube had some 12m active users .

The number of users (particularly the number of active users) is a very major factor explaining the value given to these companies. When the companies are sold, the acquirer is paying much more for the company and its users than they would have been willing to pay for just the staff, tangible assets, technology and any other intellectual property.

To generate a return on their investment, the company must turn the users into a revenue stream: users must be monetized. The most obvious way for a free service to monetize its users is by selling the users’ screen space to advertisers.

Example #1 of successful monetization: Facebook advertising

Here is an outline of how Facebook advertising works. (For far more detail and the latest status, see Facebook’s own guidance material ). Facebook offers advertisers access to their 1.4 billion users, over 900 million of whom are said to access Facebook every day. Random advertising to millions of users would be expensive and largely ineffective, so Facebook provide advertisers with the ability to target users based on a number of factors, which they describe as follows :

•Location Reach your customers in the areas where they live or where they do business with you. Target adverts by country, county/region, postcode or even the area around your business.

•Demographics Choose the audiences that should see your adverts by age, gender, interests and even the languages they speak.

•Interests Choose from hundreds of categories such as music, films, sport, games, shopping and so much more to help you find just the right people.

•Behaviours You know your customers best, and you can find them based on the things they do – such as shopping behaviour, the type of phone they use or if they're looking to buy a car or house.

•Connections Reach the people who like your Page or your app – and reach their friends, too. It's an easy way to find even more people who may be interested in your business.

•Partner categories These are targeting options provided by third-party data partners. With Partner Categories, you can reach people based on offline behaviours people take outside Facebook, such as owning a home, being in the market for a new van or being a loyal purchaser of a specific brand or product. Facebook has partnered with Acxiom, Epsilon, Experian Marketing Services, Oracle Data Cloud (formerly Datalogix), and Quantium to activate Partner Categories in specific markets. These third-party partners collect and model data from a variety of sources, like public records, loyalty card programs, surveys and independent data providers.

Facebook charges their advertisers by results: an agreed fee for each action taken by a user interacting with an advertisement. So each time a user likes an advert, or clicks a link to a webpage, or views a video from the advert, or joins an advertised event, or downloads an advertised app, or performs any of the other actions that Facebook makes available to advertisers, Facebook charges the advertiser a fee.

This means that it is very much in Facebook’s interest to maximise the effectiveness of each advert that they display to a user. One way they do this is by helping the advertiser to target the adverts to the users who are most likely to respond, using the targeting described earlier. Facebook then calculates a value for each advert, by combining the likelihood that a user will click on the advert and the fee that Facebook will receive. These values are then used in an auction to decide which adverts will be shown to which users, how often and when, because there will be many advertisements competing for the opportunity to be clicked on by a user whenever they view a page and Facebook wants to maximise the probability that the displayed advert is one that the user is happy to see and respond to.

Facebook’s algorithms have been tuned to maximise effectiveness and they are also used to help an advertiser to decide how to target their advertisement and how much to bid to Facebook for their place in the auction. A broadly similar mechanism is used by Google.

Example #2 of successful monetization: Google Ad words®

Google Ad words are the mechanism that determine which advertisements appear alongside Google searches. Advertisers choose which keywords they want to buy, so that if a user searches for those terms their advert is given an opportunity, instantaneously, to bid against other advertisers for the benefit of being displayed.

The screenshot below illustrates some of the guidance that Google gives to potential advertisers to help them to choose the search terms that they may wish to buy. This example is for someone promoting a cybersecurity product or service.

Search popularity indicates the number of searches for a keyword that meet the chosen criteria, to get an idea of how much monthly traffic the advertiser can expect on average from a keyword if they add it to a campaign .

The advertiser sets the fee they are willing to pay for each click on their advert (and a daily budget to control their financial exposure). A real time ad auction happens with each Google search to decide which ads will appear for that specific search and in which order those ads will show on the page. Each time an Ad Words ad is eligible to appear for a search, it goes through the ad auction. The auction determines whether or not the ad actually shows and in which ad position it will show on the page. Google’s explanation of the auction process is this :

Here's how the auction works:

When someone searches, the Ad Words system finds all ads whose keywords match that search.

From those ads, the system ignores any that aren't eligible, like ads that target a different country or that are disapproved .

Of the remaining ads, only those with a sufficiently high Ad Rank may show. Ad Rank is a combination of your bid, ad quality and the expected impact of extensions and other ad formats.

Like Facebook, Google seeks to maximise its revenue by displaying adverts that are most likely to be clicked on and that will generate the highest revenue to Google for that click.

Personal Data collected about you

We saw earlier that Facebook uses a variety of sources of personal data to target its adverts and that this data is collected from a variety of sources.

Google also collects a wide variety of personal data, as it makes clear to anyone who takes the trouble to read its privacy policies

When you use our services – for example, carry out a search on Google, get directions on Google Maps or watch a video on YouTube – we collect data to make these services work for you. This can include:

•Things that you search for

•Websites that you visit

•Videos that you watch

•Ads that you click on or tap

•Your location

•Device information

•IP address and cookie data

If you are signed in with your Google Account, we store and protect what you create using our services. This can include:

•Emails that you send and receive on Gmail

•Contacts that you add

•Calendar events

•Photos and videos that you upload

•Docs, Sheets and Slides on Drive

When you sign up for a Google account, we keep the basic information that you give us. This can include your:

•Name

•Email address and password

•Date of birth

•Gender

•Telephone number

•Country

Google explicitly states that it analyses your emails and other uploaded content :

Our automated systems analyze your content (including emails) to provide you personally relevant product features, such as customized search results, tailored advertising, and spam and malware detection. This analysis occurs as the content is sent, received, and when it is stored.

Facebook similarly discloses the data it collects and uses and, just as Facebook does, Google uses personal data to target adverts :

We try to show you useful ads by using data collected from your devices, including your searches and location, websites and apps that you have used, videos and ads that you have seen and personal information that you have given us, such as your age range, gender and topics of interest.

If you are signed in, and depending on your Ads Settings, this data informs the ads that you see across your devices. So if you visit a travel website on your computer at work, you might see ads about airfares to Paris on your phone later that night.

Targeting Adverts by your mood

Advertisers know that people are more likely to buy when they are in a positive mood, so companies want to be able to assess users’ mood and to target adverts accordingly. Apple has filed a patent about mood sensing and advert targeting

Google has filed a patent application to use a device similar to Google Glass (or a further development) to track what advertisements the wearer is looking at and how their mood changes as a result. From the patent application:

In one embodiment, server system 160 may compare an identified item against a list of advertisers or advertising campaigns to see if the advertisement is registered for pay per gaze billing. Under a pay per gaze advertising scheme, advertisers are charged based upon whether a user actually viewed their advertisement (process block 565). Pay per gaze advertising need not be limited to on-line advertisements, but rather can be extended to conventional advertisement media including billboards, magazines, newspapers, and other forms of conventional print media. Thus, the gaze tracking system described herein offers a mechanism to track and bill offline advertisements in the manner similar to popular online advertisement schemes. Additional feature of a pay per gaze advertising scheme may include setting billing thresholds or scaling billing fees dependent upon whether the user looked directly at a given advertisement item, viewed the given advertisement item for one or more specified durations, and/or the inferred emotional state of the user while viewing a particular advertisement. Furthermore, the inferred emotional state information can be provided to an advertiser (perhaps for a premium fee) so that the advertiser can gauge the success of their advertising campaign. For example, if the advertiser desires to generate a shocking advertisement to get noticed or a thought provoking advertisement, then the inferred emotional state information and/or the gazing duration may be valuable metrics to determine the success of the campaign with real-world consumers.

Last year, it was reported that Spotify was launching a playlist targeting service to enable advertisers to target adverts according to the mood of music being played.

The interest in users mood raises the question of whether advertisers might seek to manipulate your mood to make you more likely to buy. A recent controversial experiment by Facebook tested whether users’ moods could be changed by manipulating their news feed. According to the Washington Post, Facebook

“tweaked the newsfeed algorithms of roughly 0.04 percent of Facebook users, or 698,003 people, for one week in January 2012. During the experiment, half of those subjects saw fewer positive posts than usual, while half of them saw fewer negative ones. To evaluate how that change affected mood, researchers also tracked the number of positive and negative words in subjects’ status updates during that week-long period. Put it all together, and you have a pretty clear causal relationship.”

The results were published in the peer-reviewed journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America as Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks .

The power of social networks to influence user behaviour is causing some concern. According to a Washington Post experiment , “as much as 72 percent of the new material your friends and subscribed pages post never actually shows up in your News Feed.” and in a recent study from the University of Illinois, 62.5 percent of participants had no idea Facebook screened out any posts. That would seem to provide the means to influence political attitudes because, according to the Washington Post (citing a recent survey by the Pew Research Center ) a majority of American Internet users now get political news from Facebook

Who Owns Your Data – including User-Generated Content?

Many sites’ Terms and Conditions of Use make it clear that any data collected about you or generated by you (or about you by others) may be kept, shared and used in a wide variety of ways. Few Internet users read the terms and conditions of the services that they use before accepting these terms (so their consent can hardly be considered to be informed consent). As we saw in my Big Data lecture, a surprising amount of data is collected and stored: Max Schrems compelled Facebook to tell him what they knew about him .

In 2011, Schrems used European data privacy laws to file a request for his personal data from Facebook. Facebook provided him with a CD that had 1,222 pages of data chronicling about 3 years of his use of the service. After reviewing the data, Schrems discovered that Facebook had retained deleted chat conversations, event invitations he did not respond to, pokes, and details on his physical location identified by IP addresses, among other data which he never agreed to share. And the 1,222 pages only contained data from 23 out of the 84 categories Facebook has.

Facebook uses much of this data to target adverts. If you want to see what Facebook is using to target you personally, log in to your Facebook account, go to "Facebook.com/ads/preferences" and explore the categories, which include Lifestyle/Culture, News/entertainment, Business/industry, People, Hobbies/activities, Travel/Places/events, Technology, Education, Shopping/Fashion, Food/Drink, Sports/Outdoors, Fitness/Wellness. In each category there are many subcategories: Lifestyle/Culture contains a remarkable range: for example, Judaism, Rhombus, Soho, Citrus, Portuguese language, Nobility, Piccadilly, Asia, Society, Prophets and messengers in Islam, Instant messaging, Universe, Mezzo-Soprano … and many more, each with an explanation of why Facebook has decided that this is one of your interests). For example:

Books - You have this preference because we think that it may be relevant to you based on what you do on Facebook, such as Pages you've liked or adverts you've clicked.

MIT - You have this preference because we think it may be relevant to you based on your Facebook profile information, your Internet connection and the devices you use to access Facebook.

Brain & cognitive Sciences - You have this preference because we think it may be relevant to you based on your Facebook profile information, your Internet connection and the devices you use to access Facebook

BFI Southbank - You have this preference because you liked a Page related to BFI Southbank.

Arts and Music - You have this preference because we think that it may be relevant to you based on what you do on Facebook, such as Pages you've liked or adverts you've clicked.

Royal Family - You have this preference because you liked a Page related to Royal family.

Smart Meter - You have this preference because you clicked on an advert related to Smart meter.

Other websites also collect large amounts of personal data (and often share it with Google, Facebook and others). Google brings together data from your use of all its products, unless you have selected do not use private results in the private results section of your search settings page and turned off web and app activity and any other necessary controls in your activity controls page . Google helpfully explains:

When Web & App Activity is on, Google saves information like:

Searches and other things you do on Google products and services, like Search and Maps

Your connection information, including location, language, and whether you use a browser or an app

Ads you respond to by clicking the ad itself or buying something on the advertiser’s site

Your IP address

Results that are returned, including results from information on your device (like recent apps or contact names you searched for) and search results from other Google products

Note: Activity may be saved even when you’re offline.

We saw in my Big Data lecture just how revealing search histories can be, when we looked at what could be seen in the pseudo-anonymised AOL search dataset.

The question of who owns your data increasingly arises when a user dies, because their various online accounts may contain photographs or other data and documents that their family would like to keep but which they cannot access without the passwords. Even if the deceased has explicitly transferred ownership of their online data in their will (which is rare), online service providers may be unhelpful in giving access. This can even be a problem for executors who need to access online bank accounts – perhaps to stop or to restart direct debits for mortgage payments or family health insurance for example. The legal issues have been explored in a 2013 paper What Happens to My Facebook Profile When I Die?' : Legal Issues Around Transmission of Digital Assets on Death, by Lilian Edwards (University of Strathclyde Law School) and Edina Harbinja (University of Strathclyde Law School; University of Hertfordshire).

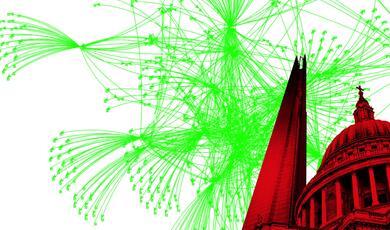

The Filter Bubble

Trying to be helpful (and to keep their users happy and online), Google, Facebook and other sites tailor the services they provide to their users, using the same sort of data and algorithms that they use to target advertising for their clients. The result is that users get more of what they like or read at length and less of what they skip over quickly. Over time, this shapes what they see to reflect and therefore reinforce their existing opinions and prejudices. This effect has been described as the filter bubble.

The origin of the term is explained in an article in the MIT Technology review as follows:

The term “filter bubble” entered the public domain back in 2011when the internet activist Eli Pariser coined it to refer to the way recommendation engines shield people from certain aspects of the real world.

Pariser used the example of two people who googled the term “BP”. One received links to investment news about BP while the other received links to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, presumably as a result of some recommendation algorithm.

This is an insidious problem. Much social research shows that people prefer to receive information that they agree with instead of information that challenges their beliefs. This problem is compounded when social networks recommend content based on what users already like and on what people similar to them also like.

This is the filter bubble—being surrounded only by people you like and content that you agree with.

And the danger is that it can polarise populations creating potentially harmful divisions in society.

One way to reduce the filter bubble (and targeted adverts) is to log out of Google, Facebook and all other websites as soon as you stop using them (to limit their ability to track your browsing and app usage), to use the private browsing and do not track options in your web browsers whenever possible, to set the option to clear all cookies whenever you close your browser (and close it often) and to use https://startpage.com as your search engine (which uses Google for its searches but always through a proxy, so that Google doesn’t see that it is you doing the search and cannot easily correlate searches done at different times).

Ad Blocking

Installing and using one or more ad blockers gives you greater control over how commercial companies can use your personal data. I use Firefox as my browser because it is open source and maintained by software developers who use it themselves and some of whom are fanatical about privacy. I have installed the Adblock Plus and PrivacyBadger blockers and I disable JavaScript where I can. This level of protection may sound like paranoia but security experts increasing say that browsing without ad blockers is dangerous. On 15 August 2016, the security specialists Kaspersky Lab announced :

This morning, we encountered a gratuitous act of violence against Android users. By simply viewing their favorite news sites over their morning coffee users can end up downloading last-browser-update.apk, a banking Trojan detected by Kaspersky Lab solutions as Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Svpeng.q. There you are, minding your own business, reading the news and BOOM! – no additional clicks or following links required. And be careful – it’s still out there.

It turns out the malicious program is downloaded via the Google AdSense advertising network. Be warned, lots of sites use this network – not just news sites – to display targeted advertising to users. Site owners are happy to place advertising like this because they earn money every time a user clicks on it. But anyone can register their ad on this network – they just need to pay a fee. And it seems that didn’t deter the authors of the Svpeng Trojan from pushing their creation via AdSense. The Trojan is downloaded as soon as a page with the advert is visited.

So just connecting to a website with a malicious advert can compromise your phone or computer.

Differential Pricing and Discrimination

When you buy something online, do you assume that the products you see and the prices that you are offered are the same as those offered to everyone else? Or the same as you would have seen ten minutes ago, or yesterday? Think again!

On-line retailers, travel firms, hoteliers and others want to maximise their profits as much as advertisers do, and they use the same sort of personal data and algorithms as we have seen are used to target adverts .

If you look for airline tickets or a hotel on a website and then compare with prices on other websites before returning to the first, you may find that the price has gone up. If you do, it may be because someone else has just bought the lower priced ticket or room – but it might also be that the website has determined that you are about to buy and that you might accept a higher price rather than the inconvenience of repeating all the comparisons.

The algorithms get more detailed and sophisticated every month. An article in the New York Times in 2012 said

At a Safeway in Denver, a 24-pack of Refreshe bottled water costs $2.71 for Jennie Sanford, a project manager. For Emily Vanek, a blogger, the price is $3.69.

The difference? The vast shopping data Safeway maintains on both women through its loyalty card program. Ms. Sanford has a history of buying Refreshe brand products, but not its bottled water, while Ms. Vanek, a Smartwater partisan, said she was unlikely to try Refreshe.

So Ms. Sanford gets the nudge to put another Refreshe product into her grocery cart, with the hope that she will keep buying it, and increase the company’s sales of bottled water. A Safeway Web site shows her the lower price, which is applied when she swipes her loyalty card at checkout.

Safeway added the personalization program to its stores this summer. For now, it is creating personalized offers, but it says it has the capability to adjust prices based on shoppers’ habits and may add that feature.

and

Catalina, a marketing company that tracks billions of purchases each year, is using a shopper’s location in store aisles to refine offers. Last year, Stop & Shop’s Ahold division introduced a mobile app, now run by Catalina, that allows shoppers to scan products. When they do, Catalina identifies them through their frequent shopper number or phone number, and knows where in the store they are. Special e-coupons are created on the spot.

“If someone is in the baby aisle and they just purchased diapers,” said Todd Morris, an executive vice president at Catalina, “we might present to them at that point a baby formula or baby food that might be based on the age of their baby and what food the baby might be ready for.”

How much is your personal data worth to criminals?

Here is what Avast Software, an IT security company says that data sellers are charging for the following:

•Credit cards without a balance guarantee: $8 per card (number and CVV

•$2,000 balance guarantee: $20 per card (number and CVV)

•Driver's license scans: $20

•Email addresses and passwords: $0.70–$2.30

•Social Security numbers: $1 ($1.25 for state selection)

•PayPal credentials/access: $1.50

Conclusion

Your time and your personal data are valuable to commercial companies and that value is increasing. The amount of data they collect and store gives them increasing power: power to make money of course, but also power that could be used for other purposes. Media companies have always had the power to influence attitudes, but the personal data that is held by Internet companies and their ability to analyse and correlate that data gives them unprecedented power to address people individually and personally, or as highly selected groups. It also enables them to influence or to discriminate against individuals or groups with impunity, because the algorithms for big data analysis are usually commercial secrets.

It is fundamental to democracy that there should be oversight and accountability to constrain the abuse of power, but technology has moved much faster than regulation, and multinational companies have become too powerful for any but the largest (or most authoritarian) nations to control. It is not clear where this will lead us; while we wait to find out, we can at least assert some control over our personal data by remaining anonymous where we can and by using the technical means that I described earlier. But free services have to be paid for somehow and the battle has only just begun between adblockers and free sites that rely on advertising. For these and many other reasons the future Internet will look very different from the Internet today.

© Martyn Thomas CBE FREng, 2016

Part of:

This event was on Tue, 18 Oct 2016

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login