The British and American Constitutions

Share

- Details

- Transcript

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

Britain, as is well known, has an unwritten constitution. The United States has the world's oldest written constitution. How has this affected their constitutional development? Many in Britain are calling for a constitution.

What does American experience have to tell us about the likely consequences?

New York University in London jointly with Gresham College

Download Transcript

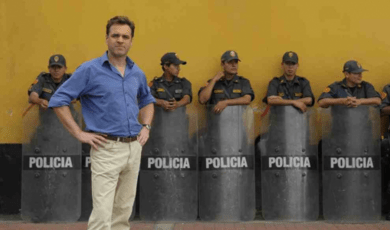

Professor Vernon Bogdanor

and

Professor Cristina Rodriquez

Vernon Bogdanor

Britainand America seem to think in the same ways, but they actually think in profoundly different ways about government. It was well summed up once by Oscar Wilde, who said that Britain and America are divided by a common language. A lot of people read Oscar Wilde these days, but I don’t think many people read Dickens, but Dickens also had a very interesting comment on the British Constitution, which he actually called the English Constitution. In his last completed novel, Our Mutual Friend, Mr Podsnap says: “We Englishmen are very proud of our Constitution. It was bestowed upon us by providence. No other country is so favoured as this country.”

In 1908 these views were echoed, perhaps strangely, by the American Professor of Government at Harvard, Lawrence Lowell, when he said:” The typical Englishman believes that his government is incomparably the best in the world. It is a thing above all others that he is proud of. He does not of course always agree with the course of policy pursued, but he is certain that the general form of government is well nigh perfect.” Fifty years later, another visiting American said something similar, an American academic sociologist, called Edward Shills. He attended a dinner party at a British university, and was surprised to hear an eminent man of the left to say, in utter seriousness, that the British Constitution was as nearly perfect as any human institution could be, and he was rather more surprised that no one even thought it amusing!

I do not believe people would think it in that way today, and one sign of that is that, as I think most people here know, our Constitution has undergone a tremendous amount of reform, particularly since 1997. Of course, the reforms began before that, indeed, they arguably began when we joined the European Community, as it then was, in 1973. But the real pace of reform increased from 1997, and I managed to list 15 major constitutional reforms since 1997. You will be glad to hear that I am not going to read out this list of 15 reforms, and I suspect most of them are very familiar to you. Devolution to the non-English parts of the United Kingdom – Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, the Human Rights Act, and reform of the House of Lords are probably the major reforms, plus a directly elected Mayor for London, the first in British history.

It is perhaps not accidental that all of these reforms move us into an American direction. The devolution reform sets up something of a quasi-federal system of government for Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland because for the Scots, I think, Westminster is now a federal Parliament – it deals with foreign affairs, major economic matters, and defence, but not with domestic matters, like health, education and transport. That is moving us slightly in an American direction.

The Human Rights Act is a movement towards a Bill of Rights. Although it has not quite got the status of the American Bill of Rights, but it is moving in that direction.

Reform of the House of Lords is seen by the Government as a step towards an elected upper house, although we are a long way from that yet. The only people who are elected to the upper house are the hereditary peers, by a British paradox, because the hereditary peers elect ninety of their number from an electoral college to participate in the Lords. That is the only elected element, by a unique paradox. Every other peer is appointed, but some of the hereditary peers are elected. However, the Government say they want to move towards an elected house, and of course that would move us in an American direction as well.

The directly elected Mayor moves us in an American direction, but perhaps even more important is the fact that all these reforms seem to imply that Parliament is no longer as supreme as it once was. Of course, one of the main differences between Britain and America is that we believe in, or did believe in, the principle of the sovereignty and the supremacy of Parliament, whereas the Americans believe that there is a higher law over and above their legislature, namely the Constitution, and that this limits what Congress can do. We never used to believe in that, but we are moving in that direction, though we are not there yet. So you can say that we are moving in an American direction and that our Constitution is more American than it was in the past.

These changes, which I think are very radical, have not been noticed by many people, for a number of reasons. Firstly, they were fairly piecemeal and unplanned. We did not do what the Americans did in 1787, which is to get together in Philadelphia to write a new Constitution. No one suggested that. We are doing it in an unplanned way, and I think we are doing something fairly unique in the democratic world, which is converting an unwritten Constitution, or an uncodified Constitution if you like, into a written or codified Constitution, but doing it in a piecemeal and ad hoc way – not in one fell swoop, as the Americans did. I think there are two reasons for this.

The first is that no one is quite clear on what the final stage should be. Has devolution run its course or will there be any devolution in England? Should the Human Rights Act be strengthened? Should there be a British Bill of Rights, which is something under consideration by the Government at the moment? Should we move further in House of Lords reform? Should we go towards a fully elected second chamber or even a partly elected second chamber? These questions are still undecided, so there is no point at the moment in drawing up a constitution when we do not know what it would be like – we do not know what the final resting place will be.

But I think there is a second reason why we have not yet got a constitution, and it is this: that the British people, and I think here is a great contrast with the Americans, the British people, outside Northern Ireland, are not very interested in constitutional questions. A survey was done in 1997 by our king of opinion pollsters, Sir Robert Worcester, who, not coincidentally I think, is an American. In his survey he did 16 types of issues, and found that the ones which people thought least important were constitutional issues, which came 16th out of 16, rather sadly, I have to say, for the sale of my books! People are not very interested in those issues.

Even in Scotland, where there was demand for devolution, opinion surveys show that the primary reason Scots want devolution is not for purposes of self-government, but as a means to a further end, the end being better public services, more money coming into Scotland, and so on, and the Scots believe that devolution will bring them that. They may be right, they be wrong, but that is what they believe.

In great contrast with Americans I think, the British, as a whole, believe not so much in procedures but in substance. The issues that interest British people are not constitutional matters, but the questions concerning the health service, the education system, transport, the economy, and so on. You may think that from that point of view the British are more or less mature than the Americans – that is obviously a judgement you must make. But I think that is actually the case; that is the position as regards constitutional reform. I think it is confirmed by the very low turnout in the various referendums on constitutional reform outside Northern Ireland.

Northern Irelandis an exception. The referendum on the Belfast Agreement in 1998 had an 80% turnout.

We also had a referendum a year later on whether we should have a directly elected London Mayor, the first in British history. People had been clamouring for years for an elected major; they said it is scandalous that London has no authority, no mayor, there is just the boroughs, but no one to speak for London. So you would think the turnout would be very high, but in fact, it was only 34%. Just one third could be bothered to vote, and that is roughly the turnout in the elections for the Mayor of London as well.

The turnout for the Welsh devolution referendum in 1997 was just over 50%; only one in two could be bothered to vote.

So it is clear that constitutional issues lie near the bottom of most people’s list of priorities.

It is worth asking why we have been happy with having what some people call an unwritten constitution for so many years. As I implied a few moments ago, the term “unwritten” is a misnomer. It is not as if we pass our rules of government on from generation to generation by word of mouth. One generation does not tell another generation “These are rules,” orally as it were. The rules are written down, they are written down in all sorts of places, but the difference between Britain and almost every other democracy is you cannot find all the rules in one place.

In America, you can buy a copy of the Constitution, you can read it in about half an hour, and get a rough idea of how American Government works. The American Constitution is in fact the oldest written constitution still extant, lasting since 1787. In a sense it is unusual in its longevity. Many European countries have had a large number of constitutions in that time. France has had sixteen during that period. There is a famous story about someone who went into a shop in Paris and asked for a copy of the French Constitution, to receive the reply, “We do not sell periodicals here!” So the American constitution is unusual from that point of view.

But we do not have that, and it is worth asking why. I think there are two reasons: one historical; and one conceptual.

Other countries have constitutions when they began, either with freedom from colonial domination, and that of course was the case with America, India, African countries and so on, or when they began, for one reason or another, with a

new regime – France in 1789 after the Revolution, Germany in 1949 after the Second War, Italy in 1947 after the War, and so on.

However, Britain never began in that sense; we evolved. We have not had a break in our constitutional development since the 17th Century. At that time we had a Civil War, and then we did have a Constitution, drawn up by Oliver Cromwell; the Instrument of Government of 1653. It was not a very successful Constitution because it was set up after Cromwell had abolished the House of Lords, but shortly after promulgating this Constitution, he also abolished the House of Commons, so it was not terribly successful. Then the monarchy returned in 1660 and, significantly, we called that the Restoration, as if nothing had changed and it was an evolutionary process. The main change that occurred was that the powers that had previously been with the monarch went to Parliament, but they were still unlimited powers. In the 17th Century the battle was between whether the King or Parliament should have absolute power; it was not whether those powers should be limited. So the point I am making is that we never had a constitutional moment, in the sense that America, or France, or Germany, or Italy. Almost every other democracy you care to name has had a constitutional moment, but since we did not have one, we never saw a need for or any virtue in a written constitution.

But the second reason why we have not had a constitution is a conceptual reason, and I have hinted at it already: that if Parliament is supreme and sovereign then there is no point having a constitution. Or perhaps you could sum up the British constitution in eight words: what the Queen in Parliament enacts is law. Another British novelist understood that very well: Anthony Trollope, in his novel The Prime Minster, when the Duchess of Omnium says of Britain that, “It seems to me anything could be constitutional or not, just as you please.” Trollope says it was clear she devoted a lot of time to studying this question, because of course that is absolutely correct – anything can be constitutional or not.

If Parliament is sovereign, there is no point in having a constitution, because what a constitution normally does – the American one for example – is to demarcate some matters which are fundamental from some matters which are less fundamental. Because of this, the fundamental matters can usually only be revised, if at all, by some special amending process, which is much more difficult than passing an ordinary law, and some things cannot be revised at all. For example, in America, you cannot deprive a state of its representation in the Senate without its consent. In Germany, the first articles of the constitution, relating to the federal system and civil liberties, are unamendable – they cannot be changed at all, however large the majority – and that is an obvious response to the Hitler regime, that civil liberties cannot be altered or changed. But we, in Britain, do not understand what fundamental law means, or at least we did not until recently. For us it is all exactly the same: you can pass a law relating to civil liberties with the same ease as one relating to, shall we say, municipal drainage. So it has been pointless to draw up a written constitution, and if we do have a constitution, you can only have it if you remove the principle of the sovereignty of Parliament; that must be a consequence of having one. So this is the second reason why we do not have a constitution, and what it means is our system does not have the legal checks and balances, the legal limits to power, that other systems have.

This does not of course mean that our system of government is tyrannical; what it means is that the limits on government are non-legal limits – limits in terms of convention which reflect social attitudes – so there are simply certain things Government just does not do. In theory, the Government could pass a law saying that next Monday all red-headed people will be executed, but we all know that will not happen, or at least we hope it will not happen! But at any rate, one of the reasons why we are moving towards a constitution, I think, is that people are less happy with this system. Most of the 15 reforms I alluded to earlier have been produced by a Government of the left, a Labour Government, and I think that is not wholly accidental. This is because the Labour Party in the past, and many people who were not in the Labour Party, thought that the best check on Government was something called the swing of the pendulum. This is the idea that one party would be in power and might produce policies you did not like, but in five years’ time or ten years’ time, the opposition would get in, and so governments would need to be careful of what they did for fear of what the opposition might do when they got to power. Therefore this swing of the pendulum was a force for moderation. But in 1979 it seemed that the pendulum stopped swinging, and the Conservatives were in power for 18 continuously years and they did things which people on the left thought would not happen in a country with a constitution – people on the left argued they went much too far. So, when the Labour Party came to power, they decided that one of their major policies, one of their major principles, was to reform the constitution.

A certain phase of constitutional reform finished in 2007 I think, when Tony Blair left office, and some people thought that was the end of that aspect of government. But Gordon Brown, as one of his first acts as Prime Minister, produced a Green Paper on constitutional reform, and a number of times he has said that constitutional reform is going to be a major theme of his Government. I think we are entering a second phase, and I want to distinguish this new second phase from what has happened up to now.

I described the first phase very briefly but I want to ask what difference it will actually make to anyone living in England, and after all, 85% of the population of the United Kingdom do live in England. Someone in England may say, “Well, we do not want devolution – let the Scots have it if they want, but we do not want that ourselves, and we’re not too worried about the House of Lords one way or the other – it does not impinge on our lives very much. The Human Rights Act, all

very well, but we hope, like most sensible people, to keep out of the hands of lawyers, and it does not actually mean very much to us, so it makes very little difference.” What this first phase has done has been a redistribution of power between elites, between elites in London, on the one hand, Westminster on the one hand, and Edinburgh, Cardiff and Belfast – that’s, if you like, power going downwards – and power going sideways, if you like, to the judges – the judges now have much more influence than they did have.

Therefore, if you want to be cynical you may say it is a way in which the elite have decided how to divide power. That in itself is not necessarily something to be criticised, because power is now much more dispersed than it was. Britain is a much less centralised and concentrated state than it was in 1997. The political philosopher Thomas Hobbs once said that liberty was power cut into pieces, and I think this first phase has tended to cut power into pieces to limit what the Government has done. I think this goes against a lot of the popular caricatures of the Blair and Brown Governments, as Governments which sought to concentrate powers in their hands. Whether you think they are good Governments or not, they have dispersed power much more than any Governments in British history I think.

Nevertheless, you may say a weakness of it all is that it does not give the ordinary, non-political person, who does not want to go to the courts, a greater share of power or influence on Government. I think that is what this second phase of reform, which Gordon Brown has announced though not yet implemented, is designed to secure. It is designed to secure something that we face in common with a number of other European democracies, and perhaps also the United States, though I am less sure about that. It is to cure a condition that I think is typical not just of us but of other democracies, and we can see the surface signs of this disease all over in a sense of disenchantment with politicians and a lack of trust in politics. This is manifested for example in very low turnout in politics. In the Election of 2001, just 58% voted. That would be a high figure in America, but it is a low figure for here. In 2005, just 62% voted. The figures are particularly low for young voters: of the 18-24 year olds, just 37% voted, and amongst females between 18 and 24, just 33% voted – that is just one in three.

We hear a good deal of talk about the youth vote, both in Britain and in America, but the really important vote is the grey vote, the vote of those over 75, because there are twice as many of them as there are 18-24 year olds and they are twice as likely to vote. Their participation rate is 75%, although many of them find it difficult to get to the polls, so the vote politicians ought to be courting is not the young vote but the older people. The young vote is a serious problem, and it led to my receiving a mark of distinction which I suspect no one else in this room has ever had, when I was rung up before the last election by the journal Cosmopolitan. I thought perhaps they wanted my photo on the cover, but that was not what they were after! What they were looking for was finding out how they could persuade young women between 18 to 24 to vote in elections. Having to think quickly on the telephone, I said that they might have interviews with the three party leaders on matters of interest to young women, which they did, but it did not make any difference to the turnout. But this journal, which is a fairly popular journal, is very concerned, and I think rightly, that so few young people, particularly so few young women, actually vote in British elections. That is one symptom of the problem.

Another symptom is the fall in party membership. Fifty years ago, one in 11 of us belonged to a political party. Now, one in 88 of us do. The figure has fallen drastically. You can put the point in another way: the National Trust has about a million members, which is more than all the political parties put together. So people are joining, but they are not joining political parties.

However, these phenomena are not peculiar to Britain. They are common to almost every European democracy, where turnout levels are falling. The recent French Presidential Election, which had a turnout of over 80%, is very much an exception. Everywhere, turnout levels are falling from what they were, say, in the 1960s, and people do not trust political parties, right across Europe. There was a recent survey of the Euro Barometer, which covers all the European Union countries, and it found that just 17% said they trusted political parties, 49% said they trusted the churches, and 65% trusted the police. Gallup International did a survey in 2005 in which 79% said democracy was the best form of government, but 65% said they did not believe their country was ruled by the will of the people. These percentages were highest in the most advanced and stable democracies in Europe – that is, Britain, Sweden, Denmark, France, and the Netherlands. It is clear that this is not the product of a particular institutional set-up; it applies in federal states in Europe and non-federal states, states which use proportional representation as an electoral system, states which use first-past-the-post, and so on. It is a general phenomenon in Western Europe, and we have to look very deeply at our system of representative democracy to see why this is happening.

It seems to me that the basic reason it is happening is a decline in what one might call tribal politics, the politics of ideological belief. People like myself can remember, many years ago, when voters would say, “We’ve always been Labour here,” or “We’re all Conservatives – we’ve always been Conservative.” People do not say that anymore. These general beliefs have disappeared, and politics has moved from issues – grand issues like whether we should have nuclear weapons or not, whether we should nationalise or not, whether we should decolonise or not. Those issues are no longer relevant. The issues are “more or less issues”. We all agree that we want to improve the Health Service; what we disagree about is how to do it. The disagreements are about means and not ends. Similarly, with schools: we all

agree that schools should be better, but how to do it is where we all disagree. It is very difficult to get people to the barricades for foundation hospitals or against foundation hospitals, or city academies or against city academies. It does not have the relevance of Socialism Now or Arms for Spain or whatever it is. These grand issues tend to have disappeared. So the grip of the traditional political parties upon us is much less than it was, but nevertheless, they are powerful in Central Government.

This point was well made many years ago by Gordon Brown in a Fabian pamphlet in 1992. He said this: “In the past, people interested in change have joined the Labour Party largely to elect agents of change. Today, they want to be agents of change themselves.” In other words, in a less deferential and more educated electorate, the idea of delegating all your affairs to professional politicians is no longer something that people are comfortable with, and therefore they are looking for new forms of democratic participation, some of which have been pioneered in America – much greater use of direct democracy, referendums, initiatives, particularly in the Western states, experiments with IT, electronic democracy, and so on. I think the Americans have a lot to teach us in this regard.

There is one difficulty with all this that one has to point out, and it is very difficult to resolve: if you have a more active democracy, are you already giving greater power to people like ourselves, who are already articulate and interested in the issues, as opposed, you may say, to those who need the resources of the vote much more and are not really able to go along, or interested enough to go along, to meetings and participate and so on. Oscar Wilde once said, famously, that the trouble with socialism was it took up too many evenings! Are we already giving greater power to the articulate, educated professionals, who already have a lot of power? Nevertheless, I think the next phase of constitutional reform is bound to be one of moving towards a more active democratic system. I think we have something perhaps to learn from the United States on this: of transforming democracy from one in which decision making itself is more widely spread, not just amongst elites, but amongst those who do not belong to the elites. It seems to me that the traditional constitutional forms of our system, which is a top-down system, primarily through the principle of the sovereignty of Parliament, are no longer congruent with the social forces of the edge, which demand a more direct and active system of government. I think the problem of making these forms congruent with these new social forces is one of the fundamental problems which we face in Britain at the beginning of the 21st Century.

Cristina Rodriguez

There are a number of things that Britain and the United States have in common, and a number of things that are quite different. I think that one of the things that struck me in listening to Vernon speak is that there is actually more convergence that has happened over time with respect to the Constitution, and this is for two reasons.

I will talk at some length about this, but one reason is that America has a written constitution. But we also actually have an unwritten constitution, that operates very similarly to how I understand the British constitution to operate and I’ll conclude by explaining the ways in which we have this. I think it is interesting that Britain is moving more towards codification, and over time, in American history, we have moved away from strict adherence to the text.

The other interesting dimension of conversion that struck me was that, in the description of the devolution of power as being a trend in Britain, it is actually a striking contrast to what has happened in the United States over the last 200 years. What has been happening for us is that we have moved from an extraordinarily devolved system to a system where power is much more concentrated than the framers of the Constitution ever thought it would be, both in the Federal Government and in the Presidency. That concentration has accelerated dramatically over the last eight years. Some of what is going on in the Election today, where we actually have record turnout in our primary election, including by young people, is a reaction to that concentration in power. So there are interesting parallel dynamics happening on both sides of the Atlantic.

But I thought what I would begin by doing is to talk about what it means to us to have a written, or shall we say, more appropriately, a codified Constitution, to explain how that has worked in practice, what affect it has had on American life and American Government. Then I would like to talk about the ways in which we actually have a system of constitutional governance that extends beyond the text.

It is not an understatement to say that, in the United States, the Constitution is the text of our civic religion. It has given rise to a discourse of popular ownership of government, to popular sovereignty, and a discourse of fundamental law and individual rights that the Government cannot infringe on. Most Americans are quite proud of the fact, for better or for worse, that we have the oldest existing written Constitution, and therein lies both the promise of American Government but also its problem.

I would say the existence of a written Constitution has had three primary effects on the nature of government in the United States. The first is that it constrains or inhibits flexibility in the operation of government, because the powers of government are clearly laid out in the Constitution and are not susceptible to the same evolution over time, through

convention, that they appear to be in Britain. We might think of that as a virtue, because the watchword of American constitutional law is of limited government that cannot act arbitrarily or infringe on the rights of the people; but we might also see it as a liability, in that it is extraordinarily difficult to change the way that government operates, even when it operates dysfunctionally. For example, the rule that Vernon pointed to, that the representation of each state in the Senate cannot be changed without its consent, effectively means that there is no way to change a rule by which the 35 million people in California have the same representation as the fewer than a million people in the state of Wyoming, and that has, over time, become extraordinarily problematic in the way our democracy functions.

The second way in which having a written Constitution has affected government in the United States is that it has simultaneously secured basic rights from infringement, but it has also inhibited the development or the conceptualisation of rights to a more 21st Century type of model. It is very difficult, at least at the constitutional level, to imagine rights and a rights discourse that is not consistent with the way rights were understood to exist in 1787, which was a long time ago. So we are quite path-dependent in the United States in the way that we understand rights, and the existence of our written Constitution and the constitutional culture it has established I think has an influence on the fact that we have no conception of social and economic rights in the United States that has any meaning, apart from what a legislature might decide to recognise.

And then the last major way in which our having a written constitution affects government in the United States is that it makes courts extraordinarily powerful institutions in American government and in American life. It is meant that the development of our understanding of our rights as individuals has happened, particularly in the 20th Century, primarily through the courts and through litigation. As a lawyer, that has a positive development and it is a reason why lawyers have relatively high status in the United States. But it is also a reason why lawyers are also consistently vilified in politics, because of the ways in which lawyers and courts seem to have so much control over the development of things like our conception of rights.

So I would like to explore these conclusions by looking at three different sets of issues. First, just tell you a little bit about something you may already know: why the United States adopted a written Constitution, which could be summed up in the words “It’s all Britain’s fault!” but I will put a little meat on that conclusion. Second, I want to talk about how the existence of a written Constitution has made the judiciary so powerful, and what that has meant for how we understand the development of rights. Then, finally, I will talk about the extent to which we actually have an unwritten constitution, an uncodified constitution, that has evaded some of these problems that a written constitution produces.

As Vernon mentioned, written constitutions often result when a society has experienced a cleavage or some kind of cataclysmic event, and obviously for the United States, that cataclysmic event was the Revolution. It was an act of self-definition, and often, writing something down is a way of defining oneself as a nation, as a people, and when there is a break like that, that is the sort of thing that seems like a logical thing to do. In fact, Benjamin Franklin, in a letter to a British correspondent in the late 18th Century famously said “I wished most sincerely with you that a constitution was formed and settled for America, that we might know what we are and who we are and what we have, what our rights and what our duties are.” In other words, Americans did not know who they were, and so proceeded to write down who and what they were as a way of helping to define a fledgling nation.

The framers of the Constitution had some existing models at the time. The states of the Union themselves had constitutions, but those states did not do one of the key things that the federal constitution eventually did, and that was to restrain legislative authority; to shift from a conception of parliamentary sovereignty, to supremacy of the legislature; to a conception of popular sovereignty or supremacy of the people. In many ways that was the great accomplishment of the American Constitution; to limit government by declaring a fundamental and higher law that the legislature – the equivalent of Parliament, which became our Congress – could not infringe. The reason why this seemed like the thing that was necessary to do was because of the perception – and that is was, in part, the cause of the Revolution – that in Britain that there was a split between parliamentary law and fundamental principles rooted in the common law. Therefore it was thought that what Parliament was doing was not aligned with the liberties of Englishmen, and that the Parliament could not be trusted to respect the liberties of the people. This meant that there was a need to fix what those liberties of the people were and the need to eliminate any ambiguity or possibility of deceit that the legislature or the Parliament could in fact perpetrate on the people. That was among the justifications for actually writing down principles of government.

A number of commentators have noted a variety of consequences of the writing down of the Constitution, and the first is one that I have already described: a shift in the conception from parliamentary sovereignty to popular sovereignty. This was a shift to a conception based on the consent of the governed so that all law had to proceed from the consent of the governed. Therefore the Constitution was no longer seen as a bargain between two entities, but rather as a basis and fundamental framework for society, beyond which the legislature or the executive or any organ of government could not succeed. In this sense, the significance of our Constitution is not that it is written down per se and that it is codified, but it is that the document stands, theoretically at least, as the will of the people. It is standing for the will of the people as sovereign and the branches of government that it constitutes are separate but subordinate to the people, to the higher law.

The second way in which the written Constitution changed our conception of government and can be seen as revolutionary and why we try to export it around the world, was that it recognised a shift from natural law to positive law. This was a matter of shifting from law that existed in the ether to law that was actually written down in a code, and from an ordinary conception of law to a conception of higher law, to which Vernon also alluded. This enactment of a positive code ultimately gave rise to a debate that I will talk about in a moment, about whether the Constitution exhausted all possibility of what law was in the United States, in other words, whether the rights listed in the Constitution were all the rights that we had. The fear that the Constitution would be understood to limit our rights was actually one of the reasons why the architect of the constitution, James Madison, resisted writing down what the rights of the people were, for fear that that would become an exhaustive list, but over time, that list has not been though to be exhaustive, for reasons I will describe.

The last very important conceptual shift that is related to the notion of having higher law is that this law is entrenched. The Constitution is entrenched. Congress can do nothing about it. The conception that the President is beyond the law in this day and age, theoretically cannot do anything about the existence of the Constitution. The only way that the Constitution can be changed is by an expression of the popular will through an amendment process, an amendment process that the Framers deliberately made extraordinarily difficult, so difficult in fact that, over the course of 200 years, we have only amended the Constitution 27 times, and the first ten of those happened in one fell swoop just after the Constitution was adopted. That is our Bill of Rights. So, in a way, this conception of law has actually promoted a conservatism in American government, a very slow evolution of our conception of rights in particular, and though the shift towards popular sovereignty and fundamental law is generally understood to be salutary it is also a recipe for slow adaptation, and possibly in an inappropriately slow way. We have an 18th Century Constitution for a 21st Century world, which creates a number of difficulties that have given rise to what people describe as our unwritten Constitution.

The next thing I would like to talk about is the role that courts have come to play in American life because of the existence of a written Constitution, and I think that this may be one of the major institutional differences between the United States and a place like the United Kingdom. The existence of a higher law beyond which the legislature is not supposed to extend, leads to the need for someone to interpret that higher law and bring the legislature to account, and that institution has become the courts. Because the Constitution was considered to be something of a pre-commitment strategy to remain true to the ultimate mission of popular sovereignty – something like a Ulysses tying himself to the mast to avoid the temptations of Scylla and Charybdis – the courts have played a role whereby they essentially compare legislative enactments to what the Constitution requires, and the court declared for itself very early on the power of judicial review, which is the power to declare an act of the legislature invalid under the Constitution. This is something that I understand does not make any sense in a British context, but which is fundamental to Americans’ understanding of what limitations they place on their government.

So there are different ways of thinking about who gets to interpret the text and hold the legislature to account, and scholars divide it between the catholic view of things and the protestant view of things. The catholic view of things is that it is the high priests of constitutional view – the courts who get to say what the text means; and the protestant view is that it is actually the people who get to say what the Constitution means. In fact, in the US, people do have a personal relationship with the Constitution, and believe many things about what it guarantees, including things that are not actually in the document that courts often resist. But one of the things that have developed over time, despite the existence of this idea that the people get to say in a protestant sort of way what the text actually means, is that the courts have become supreme. Therefore, instead of a concept of legislative or parliamentary supremacy, we have a concept of judicial supremancy.

As you can imagine, because the judiciary is an unelected body – it is appointed by the President, or at least the Federal Judiciary, approved by a majority of the Senate – the fact that it has this power to strike down legislation is seen as a fundamentally undemocratic thing. It is seen as inconsistent with the notion of popular sovereignty; that the organ of popular sovereignty, which is the legislature that makes the decisions, can somehow be thwarted by these unelected officials, theoretically representing higher law and the original will of the people in 1787, or 1868, when we had a second major series of constitutional reforms. So the critics of judicial supremacy, and people who point to the Commonwealth models where there is either no written or codified constitution and absolute parliamentary supremacy, or those in favour of the Canadian model where there is a Charter of Rights and judicial view but a legislature override provision whereby the Parliament can override something that the courts have declared unconstitutional, all of these people point out that this has resulted in the infantilisation of the American public. This is an infantilisation where Congress does not take seriously its constitutional duties and the people just let the courts decide, as opposed to doing what they originally thought to do, which is to hold the government to account.

In fact, there are a number of examples of this being true. The President, and not just the current President, will sometimes sign into a law a bill that he believes to be unconstitutional because he thinks the courts will fix it; or Congress, when passing a large piece of legislation, ignore some of the constitutional controversies that are the result of the legislation, because the courts will sort it out. So it leads to something of a relegation of issues to the courts that really should be for the people and their representatives to decide.

In some ways it has also made it difficult to check the process of the arrogation of power, particularly on the part of the executive. This is something that has occurred throughout our history but is particularly salient today. This is because people assume that if there is something wrong with what the President is doing, the courts will step in and fix it, but at the end of the day it is really only the people with the capacity to vote who can check the arrogation of power, and not necessarily the courts. So the Supreme Court has certainly given George Bush a run for his money in the last couple of years.

So these have been some of the consequences of having a written Constitution, and the last thing I will say about this is to give you a little taste of one of the things that may seem bizarre about American constitutional interpretation. But it is something that every judge, no matter their political persuasion, takes seriously on some level. It is that in deciding what a provision of the Constitution means and whether or not a legislative enactment is constitutional or not, one of the theories of interpretation that has become extraordinarily powerful is the theory whereby what matters is the original intent of the Constitution’s Framers. By that, I mean what was meant by the original provision of the Constitution is what should control. So you have a 18th Century document and an 18th Century mindset that was thought to have some kind of control over the way we understand the Constitution in the 21st Century. By its critics this is called the dead hand of the past, but the dead hand of the past has a very long reach in American constitutional law, and some of the ways in which this manifests itself is, for example, in the debate over the death penalty.

So, in the debate over the death penalty, the possibility that it would be a cruel and unusual punishment is essentially undermined by the fact that the death penalty was not understood at the time that the Eight Amendment was adopted to be a cruel and unusual punishment. The reason is that originalism is not required by having a written constitution but it follows logically from the existence of a written constitution, because once you put something into text, you have an author, and so, in interpreting a text, authorial intent becomes an important understanding or an important conception of what that text means. So originalism, though it is not practised by all judges, is a form of interpretation that has a particular stranglehold over American constitutional thinking, despite the fact that most people recognise it as something that perpetuates old, outmoded ideas in what should be a modern democracy.

Now, the last thing that I would like to talk about, after having spoken about the exceptional nature of our written Constitution and established its importance in the way that we understand both the concept of sovereignty in the United States and also the concept of rights as elaborated by courts reading a text using the original meaning of the text, is to talk about why we in many ways actually have a unwritten Constitution. I would also like to speak briefly about the pathologies that arise from having a written text which cannot possibly specify the answer to the myriad questions that arise when a government is in operation or, as our conceptions of rights change over time, we have had the development of what is essentially an unwritten Constitution. Therefore, what the Constitution did in 1787 was not to set up an inflexible framework beyond which we could not move, but instead, to set up the parameters for public debate, within which the nature of rights and the nature of government and the balance of powers could play out. Over time, we have developed lots of alternative sources of constitutional meaning that are not just in the original text, that we continue to parse as if it were some kind of religious document, but we also have other texts that stand alongside it. These are called by some people super-statutes or statutory enactments that Congress has passed over time that might have a resonance similar to the Human Rights Act.

So the major legislation of the civil rights period of the 1960s is thought by some to constitute legislation that is constitutional in nature – legislation that prohibits discrimination in the workplace, that prohibits discrimination in public accommodations – things that were not prohibited at the time that the 14th Amendment was adopted in 1868. The 14th Amendment was our equality guarantee but it was not understood to prohibit segregation of the races, but as the result of subsequent history, we have adopted a number of statutes that have, in some people’s eyes, acquired the status of something like the Human Rights Act, or something that is equivalent in nature to the Constitution. It is not equivalent in the sense that Congress could not change it, because the Congress does not have the power to change the Constitution, but it could repeal one of the civil rights statutes. But it is the sort of thing that can imagine would never occur, similar to the existence of the prohibition on executing red-haired people in the United Kingdom. The repeal of the Civil Rights Act, though there are some judges who believe they are unconstitutional, for arcane reasons I will not describe, is inconceivable in the United States, and thus it is understood to have constitutional status.

There are also judicial opinions that are understood to have a kind of constitutional status. So one of the major moments in which there was a shift in our understanding of the structure of government was during the New Deal period, when Franklin D. Roosevelt adopted a series of reforms to address the Depression, which fundamentally changed the nature of

American Government. It delegated a considerable amount of legislative power to administrative agencies to regulate the economy, things that were understood to be anathema in that period, up until the beginning of the Twentieth Century, but were seen as necessary to pull the country out of the Depression. The Supreme Court struck several of these agencies down, finding that they were inconsistent with the legislative power given to Congress in the Constitution, but through a series of elections, where Republicans were essentially thrown out of office, and a series of public mobilisations in favour of this New Deal that was going to save the American economy, the Supreme Court switched its point of view. One person switched his vote, and suddenly, what had had been seen as an unconstitutional delegation of legislative power became something that was perfectly permissible within the four corners of the Constitution. The Constitution had not changed, but what had changed was the popular conception of how Government should be structured and how it should be allowed to be structured to address contemporary concerns. The judicial opinions that embody this shift are understood by some people to have a kind of constitutional status as well. There were amendments to the Constitution proposed at the time to do precisely what the Court ultimately did, but because, in some ways, the Court went first, and made the change through an opinion, the change in conceptions of government was made. So there is also this understanding of major judicial opinions that, in a sense, update the Constitution as being part of our unwritten Constitution.

I will give you just one example before I close, of how this unwritten Constitution has worked in practice. The structure of executive power, or the content of executive power – the power of the President – in the American system is not very well specified. So the President is given the power as Commander-in-Chief to do whatever it is the Commander-in-Chief does, but the Constitution says very little about what that means. At the same time, the Constitution gives Congress, the legislature, the power to declare war, and if you look at the design of the Constitution, it seems like Congress essentially, if not has a co-equal position when it comes to issues of law and war, might even have a superior position to questions of war making. But what has turned out to be the case in practice is that Congress has only actually exercised its constitutional power to declare war four or maybe five times in American history, but as I am sure you all appreciate, the United States has used its military force many more times than that in its brief history as a country.

What has happened over time is that the power of the executive has become one where it has become the prime mover when it comes to committing troops to different types of entanglements around the world, whether they be called war by Congress, or whether they not be called war but essentially amount to it. That is a way in which the structure of government has actually shifted over time in response to the exigencies of political circumstances; that you have in the President a power that is concentrated and therefore a power that is much more able to respond to military threats or other perceived threats around the world, and Congress, which is a large and clunky body and can never come to agreement on most anything, is not an effective body in responding to threats that the American population perceive. So the shift has been, despite the constitutional language, towards a lot of power being arrogated in the executive.

Of course, the question is whether this is constitutional or not, and in some sense, it does not really matter whether it is constitutional, because it is what the President does, and in a sense, what the President does becomes the practice. But, especially in the last couple of years, the Supreme Court has actually been a major player in attempting to limit what the President is able to do. In this sense, the existence of our written Constitution and the subsequent rise of judicial supremacy is playing a major role in limiting the powers of the President, even though the powers look dramatically different than I think was originally envisioned in the Constitution. So the Supreme Court in a series of decisions has made clear that the President is not, in fact, above the law, and for example, to establish military commissions on Guantanamo Bay, the President has to be abide by the laws that Congress has adopted, namely the uniform code of military justice. So the Court has not said that Congress itself could not create a military tribunal, like the ones that the President sought to create in Guantanamo Bay, but it has said that the President is bound by those statutes that Congress does pass in limiting executive power. So in that sense, the Court has played a role in something like shifting the balance a little bit back into Congress’ corner. This is the balance that practice had taken away, and that the power of the President had, by some measure, taken away from Congress. I think it is in that sense that the existence of our codified Constitution and a very clear conception of separation of powers has played and continues to play a major role in the way we understand the nature of our Government.

In the end I think there are two reasons why it is the case that our Constitution is in fact the oldest written Constitution. The first is that the written Constitution itself is very spare. As Vernon said, you could read it in half an hour. That does not mean you would understand everything in it in half an hour, but it is easy to read in a short period of time. It is because of that spareness that space is open for the country to adapt and the government to adapt in response to changes in nature. So that is the second way in which our Constitution has actually managed to survive, and that is that we have had a judiciary, as well as players in the political branches of government, who have over time adopted and not felt themselves bound by what was understood to be the appropriate allocation of power or the appropriate list of rights during the original constitutional moment in 1787, but instead have, in a common law fashion that we have inherited from the British, been able to adapt the liberties of Americans and the structure of government of the United States to the ways in which the world has changed.

So even the existence of a written Constitution does not obviate the need for a governing framework that changes and adapts over time. Nor does it forestall the rise of a set of customs or norms that fit within the parameters of the Constitution but are not in all cases required by the Constitution to govern a democratic society like the United States. I think it is in this sense, in light of the importance of custom and history and the slow adaptation of our governing framework to modern life, that the British and the American Constitutions may not be all that different. And in the end, what we are converging on around the world is a very similar set of governing practices.

(c) Professor Vernon Bogdanor, Gresham College, 16 April 2008

(c) Professor Christina Rodriquez, Gresham College, 16 April 2008

This event was on Wed, 16 Apr 2008

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login