Will there be a shortage of spending power?

Share

- Details

- Transcript

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

This lecture will look at the world surplus of savings as incomes gradually shift proportionally towards those who traditionally save a high proportion of their earnings and away from those who traditionally spend most of what they earn. In theory, the excess savings should be matched by higher investment. In practice this is not happening.

This is part of the lecture series, The Greatest Ever World Economic Event: How the transformation of two thirds of the world's population from starvation to moderate prosperity will affect us all.

Professor McWilliam's next free public lecture is on Tuesday the 19th of November: Should the UK Adopt Money GDP Targets?

Download Transcript

28 February 2013

Will There be a Shortage of Spending power?

Professor Douglas McWilliams

Thank you very much for joining us this evening.

As recently as 1990, the Chinese saved $153 billion a year and accounted for less than 1% of the world’s savings. This year they will save $4.5 trillion and account for 25% of the world’s savings.

In the last 8 years China’s savings have leaped from a tenth of the world’s savings to a quarter.

What I want to consider today is whether this and the industrialisation of the emerging economies more generally means that there will be a world problem of excess savings and underconsumption.

One of the consequences at which I will look more closely is the extent to which the savings glut was responsible for the mistaken decisions that led to the financial crisis which started in 2007 and the aftermath of which lingers on today.

I will suggest some measures by which we can cope better with the aftermath of the financial crisis – though my key message is that when you have made such disastrous mistakes of investor decision making, regulation and government economic policy you have to pay the price and it was always unrealistic to expect a rapid recovery.

I will look at some of the other consequences, like the extent to which China will accumulate assets abroad and the impact on investing for retirement.

We start by putting this lecture in the context of the others in the series. Then we move to looking at how high savings levels have actually been in China and how this has affected the world’s savings rate.

We will then move on to how this contributed to the financial crisis – and at what can be done to alleviate the situation.

We will then look at how the misuse of Keynesian remedies made the economic crisis so much worse than it needed to be by providing a false rationale for boosting public spending in the upswing.

Then we will turn to the impact of the Chinese savings glut on pensions and then to the ownership of assets.

Finally, I will bring in a postscript which comments on the economic issue of the day – the UK’s loss of its triple A rating with the help of some economic analysis done by my colleagues at Cebr.

How this fits into the lecture series

My Gresham lecture series examines the impact of globalisation on the Western world. In the past four lectures we have looked at the unprecedented pace at which the emerging economies have industrialised, at the ‘supercompetitiveness’ of the some of these economies, at their impact on natural resource prices and inflation, at new theories of economic growth to guide policy in the Western economies and at some practical issues like the need to restructure the costs of living and of doing business in the Western world, and especially in the UK, to deal with the implications of the emerging economies on the cost of living.

The scale of Chinese savings

One of the biggest of the impacts of globalisation is through China’s savings glut.

Traditionally large economies have had gross savings ratios to GDP of around 15% (the UK and the US) to 20% (much of Europe). But the Chinese gross savings ratio is 50%. Households account for about of half this – the rest is provided by corporations (Chinese companies make large profits but typically do not declare them officially) and the government. Western economists have consistently predicted that the savings ratio will fall but so far it has done the opposite.

The only country with a savings ratio anywhere near is Singapore. Even Japan, which once was famous for its high savings is now much closer to the developed country norm.

Since the Chinese economy was liberalised – different people give different dates though 1982 is the most commonly used, the gross savings ratio to GDP fluctuated around 40% of GDP. But since 2004 it has risen sharply to around 50% where most forecasters expect it to stay for the near future.

As I pointed out in my first Gresham lecture, Chinese GDP after remaining around 2% of world GDP for most of the 1980s and into the early 1990s started to move sharply upwards, reaching 4% of world GDP round about 2000. It is now 12% and forecast to continue to rise to nearly 15% by 2017.

The combination of a high savings ratio to GDP and a growing share of world GDP have taken Chinese savings to 6% of world GDP from less than 1% in the 1980s and 1990s.

In cash terms they have grown from $153 billion in 1980 which we noted at the beginning of the lecture to $4.5 trillion today and a forecast $6.5 trillion in 2017.

It is instructive to compare savings in the US and China. The US still has a much larger economy but a low savings ratio. China, with a relatively smaller GDP but a much higher savings ratio, had a level of savings which overtook the US in 2007. But since then it has risen dramatically and has already reached double the US level and is forecast to rise further. Now China provides a quarter of the worlds’ saving while the US provides only 12%.

Of course, the Chinese savings glut can only affect the world supply of savings if it causes a rise in the world savings ratio.

And this has indeed happened. In the 1980s and 1990s the world’s savings ratio fluctuated around 22%. Since 2001 the trend has been sharply upwards, to just shy of 25% now and is forecast to continue to rise.

Not surprisingly this has driven interest rates down. The benchmark US Treasury 10 year bond yielded about 6% at the beginning of the century but had fallen to 2-3% by 2010. Yesterday the yield was 1.87%.

What this means is that the impact of Chinese savings on the world’s savings rate is now on a scale that affects other economies significantly.

Impact on the financial crisis

The basic story of the financial crisis is well known.

Investors took on excess risk, bankrupting many banks and building societies. In the UK, the two banks that had to be bailed out were the Royal Bank of Scotland, Lloyds HBOS, though in fact it was only the HBOS part until Lloyds took it over. I was actually at the party where Gordon Brown allegedly approached Sir Victor Blank, Chairman of Lloyds Bank, and started the process of spreading the crisis to Lloyds Bank as well. Then amongst the building societies were Northern Rock, Bradford and Bingley and the Dunfermline Building Society, whose track record of economic (mis)management is such that it is difficult to believe that they were not advised by their local MP.

What is interesting about this is that in the UK the so-called casino banks were not in fact the ones that got into trouble but retail banks with investment arms and building societies or former building societies.

It is also notable that the further North a bank or building society was headquartered, the more likely it was to go bust.

Despite the fact that no businesses in the City needed to be bailed out by the government, politicians have stigmatised the City as the cause of the problems.

In fact the City is relatively good at making risky investments. Its people are very clever and work extremely hard. They are (or at least used to be) over remunerated but that is not the point. The real problems have been when the robins of the clearing banks tried to become the batmen of the investment banks.

When I was at school, people used to be pointed towards working in the clearing banks when they were considered to be not quite bright enough to go into the armed forces. Partly because no one would have ever thought of sending these people to university, they tended to know their limitations and were actually often very good bankers. The made up in understanding people for what they lacked in IQ and generally understood their customers well enough to know whether to lend to them or not.

They have been replaced by people who are mid ranking in ability but have aspirations that exceed their capabilities. When those working in the City started to make real money, others in clearing banks, without the intellectual ability or access to market knowledge to take the same risks, asked ‘Why not me too?’ And with the financial power of the clearing banks behind them they could even take on bigger risks, without having the ability to understand them.

The other elements of the crisis in the UK were either lax or incompetent regulation of financial bodies, exacerbated by the split of the powers of the Bank of England with banking regulation hived off to the FSA, and the emergence of a massive public sector deficit and burgeoning debt ratio.

This looks at face value like a case of bad behaviour by bankers and politicians. Of course with their superior access to influencing public opinion, the politicians have managed to pass much of the blame over to the bankers, who were already unpopular because they were overpaid.

But if you look underneath the surface, the problem really starts with the glut of Chinese savings.

This caused the fall in interest rates and hence investment yields.

The difficulty was that the yields that the main institutional investors targeted were based on historic data.

The FSA guidance on yields to target even as late as 2007 showed target medium term yields of 3¾ to 8¾% based on research by Price Waterhouse Coopers (PWC).

I must declare an interest because I actually tendered for the same contract that PWC won. Sir Howard Davies, head of the FSA did me the courtesy of a personal letter explaining that I hadn’t been selected because he wanted the involvement of actuaries. In my view that was a major error, since actuaries will normally only look backwards and do not have the understanding necessary to see the changing economic forces that mean that the future may not be like the past.

The yields that the FSA was encouraging investors to target for government bonds as recently as 2007 was actually more than double the current yield that is actually being achieved.

The problems of low yields were exacerbated by a second failing of the actuaries – this one with fewer extenuating circumstances – they have grossly failed to predict the scale of the increase in longevity. This has led to pension funds – which make up the largest single component of the investment community – being underfunded for direct benefit schemes.

The underprediction of the increases in longevity and the failure of yields to live up to expectations as a result of the savings glut jointly caused ill-informed western investors to invest in ever riskier asset classes to try to chase target yields based on the experience of a different era.

If you think about it, why on earth would anyone buy sub-prime mortgage debt? Surely the clue was in the name. Sub prime means that the borrowers have bad credit records and on past trends are unlikely to repay.

The slick salesmen trying to palm off subprime mortgage bonds claimed that by reslicing and dicing the mortgage portfolios, they could manage the risk. This is a pretty implausible assertion, since unless the risk is actually removed, it is still in there somewhere and bound to come out at some point.

But actually the system of lending meant that default was ensured. Most of the mortgages were sold to subprime buyers on a rising scale of interest rates. Initial interest payments were low – around 2%. Even then, about a fifth were unable to service their repayments even in the first year. But the interest rates were scheduled to rise, typically to 10% plus eventually.

This guaranteed that they would not meet repayments in most cases. But even then the slick salesmen had a solution – they rolled the repayments into increasing mortgages.

Of course this would only work while the underlying asset price continued to rise.

But the US housing market is very different from the UK market. The US has a huge land mass and varying but generally relaxed planning rules. This means that when house prices rise in the US, new house building is induced which eventually pulls prices back down again. This makes US house prices very cyclical without anything like the upward momentum that is generated by the persistent supply shortage in the UK to which I referred in the last lecture. Which in turn means that it is economic madness to bet on house prices rising continually in the US.

So sub prime mortgage bonds were a product that was bound to fail – a fact that should have been obvious to anyone with reasonable economic knowledge and a grain of common sense (admittedly a combination that is less ubiquitous than might be expected).

As a trustee of the GEC pension scheme and a member of its investment committee, I had the privilege to be present when someone flew over from Boston to try to persuade us to invest in subprime mortgage bonds in the mid-2000s.

The fact that he could afford to fly the Atlantic for just one meeting suggested that the profit margins might be quite fancy. And the fact that he needed to fly the Atlantic suggested he had run out of people in the US stupid enough to buy the bonds. Fortunately, I managed to persuade the investment committee not to buy the bonds.

Of course, sub prime mortgages were only the tip of the iceberg as far as risky lending and the search for higher nominal yields were concerned - a wide range of risky forms of lending was encouraged.

So the low yields caused by the Chinese savings glut were critical in setting up the circumstances for the world financial crisis.

Add to this lax monetary policy in the Western world (also a response to the Chinese savings glut) and a financial collapse was inevitable. This duly took place in 2007 and 2008. We are still living with the aftermath.

Did we predict the financial crisis? Well yes, actually, most economists did!

The Queen asked the famous question to the LSE ‘Why didn’t economists predict this?’

The answer is that we did. I certainly did and most of the people working in the City also did so, which is why the City did not need to be bailed out. The people who didn’t see it coming were those a bit remote from the real world like academics, the Treasury which had become heavily politicised under Gordon Brown, and some of the economists in the media.

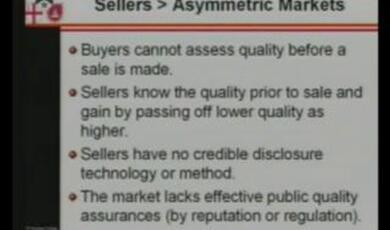

How to regulate the City

Obviously there is a great rush to shut the stable door of financial regulation now that the horse has bolted off some distance away.

I actually think that the problem with financial services was too much regulation not too little. When you regulate in too much detail – as the FSA did – you tend to miss the wood for the trees. The FSA were very good at preventing people from tripping up over exposed wires on the floor. But totally missed the exposure to loss making sub prime mortgages.

We’ve moved on from the mad world of 2007/08. Bonuses have fallen by nearly 90% and they are now paid at the top end in forms where they are recoverable if deals that looked good turn out subsequently to be loss making.

In general, my feeling is that excess pay is caused when there is sufficiently little competition for there to be excess profits. So you should focus attention on the market structure problems that generate excess profit, not on the side effect of excess pay.

You can cope with excess pay by transparency and by decent corporate governance.

My approach would be to protect the institutions, on which we all depend, but take a tough line with individuals. If you are on the board of a bank that needs to be bailed out or have been in the runup to the problems emerging, you should not expect to work in the City again. That would focus the attention of boards who until now have been insufficiently critical in their oversight of their executives.

I believe that one way of boards achieving this is to create cultures where everyone working in banks realises that it is unethical to cut corners.

We also need to adapt charging structures in fund management to reflect the reality of low yields.

In such a climate, those investing funds have to accept radically lower returns – unreasonable to charge 1% or more to manage a fund where the yield is not much more than 3% is totally unacceptable. This business model has to change.

The impact of mistaken pseudo Keynesian policies.

The Chinese savings glut had another unforeseen consequence.

It encouraged some governments – the UK was the worst example but there were others as well – to expand public spending rapidly financed by running deficits and by spending some of the temporary tax revenues that were flowing in from the overextended financial system. For most of the first decade of the 21st century the UK ran deficits of £30-40 billions at a time when we were near the top of the economic cycle. This was despite revenues reaching nearly £70 billion from the financial services sector which should have been seen as at least partly unsustainable and should have been banked for a rainy day.

Of course, when the cycle turned down and the financial sector moved from boom to bust, the deficit soared to £159 billion in 2009/10.

The basis of the heavy spending seemed to be a mistaken version of Keynesian economics. But Keynes’s demand stimulus policies were explicitly targeted at emergency and temporary measures for an economy with negative inflation and declining GDP. He never intended these policies to be applied as a long term fix for the structural problem of excess savings in a country like China, especially for an economy like the UK which until 2008 was growing and had positive inflation.

The problem of bailing out the banks will have cost the taxpayer about £120 billion eventually, after allowing for repayments of loans. By comparison, the problems of the excess deficits built up since 2000 will have cost the economy £1.5 trillion by 2025.

It is time to stop pretending that all the problems were caused by bankers. They did cause problems and, yes, they were overpaid. But to put it in context, Gordon Brown cost the taxpayer more than 10 times as much than Fred Goodwin and his colleagues in other banks. It is time for the politicians to accept their responsibility for creating the national economic crisis.

Because of likely slow growth in the UK, Cebr’s latest forecasts indicate that the UK debt ratio in 2025 will still be over 70% of GDP when most economists believe that anything over 60% is unsustainable.

Impact on pensioners

Besides being the main background cause for the financial collapse, the Chinese savings glut has other effects on us.

Let me first turn to pensioners.

After the getting their fingers burnt with high yield investments, today’s investors have reluctantly concluded that low yields are the reality at least for the time being.

Now that investors have had their fingers burnt on high yield investments, they are only able to get low yields. Even the Pensions Regulator admits that most pension schemes are underfunded and many will never be able to be fully funded while low yields persist without bankrupting their guarantors. And for those on Direct Contribution pension schemes, the annuity yields that they are able to buy are unlikely to rise much from today’s very depressed levels.

It is probable that at some point in the next 40 years the Chinese savings ratio will fall – though Singapore’s still high ratio of over 40% warns us that even prosperity and some welfare protection may not be enough to overcome the cultural factors that keep Chinese savings high.

Given this, we should expect the savings glut to persist for most of the first half of this century at least.

In turn this means low yields are likely to persist, if probably not quite as low as today, when they are distorted downwards by some specific elements of monetary policy.

And simple maths shows that current life expectancy trends and low yields mean that you have to save nearly half of pre-tax income to retire at the age of 65 on 2/3rds of your former salary. Workers could save more. But they are unlikely to do so and if they did so around the world, they would only add to the glut of savings that is a fundamental cause of the problem. So the only real solution is for people to work longer.

Japanese men, who faced the problem early because of zero interest rates and a declining population, now retire on average at 70 and will retire even later in future. Our calculation is that those joining the labour force in the UK today at the age of around 20 will probably have to work till the age of 75 or even longer.

Impact on Chinese ownership

A different effect of the high Chinese savings rate is that a country providing 25% of the world’s savings will eventually own roughly 25% of the world’s assets.

China’s share of world GDP is about 12%. As Chinese growth will eventually slow, it is likely that the share of world assets in China itself will settle close to its share of world GDP. This means that with a savings ratio about double that of the world average, roughly half Chinese assets are likely to be outside China. So far the Chinese have invested heavily in areas like Africa and South America which the West has neglected as well as in US Treasury bonds. But they will have to turn increasingly to other assets like companies and properties in the West including UK companies So my advice is that we had better start learning Mandarin now – our next bosses may be Chinese!.

Conclusion

So in this evening’s lecture we’ve seen the consequences of China’s extraordinary savings ratio as the Chinese economy becomes a very significant part of the world economy. The scale is such that it affects the way we all live our lives and will particularly affect the lives led by the next few generations.

I’d like to finish with a postscript – some calculations done by one of my colleagues Chitraj Singh Channa which casts light on why it is so difficult to get the UK economy to grow and which in turn gives an important explanation of why one of the ratings agencies has reduced the UK’s credit rating.

The graph I am showing demonstrates the difference between world GDP growth using the normal current price weighting, and the numbers you would get for world GDP growth if you weighted by UK export markets. Historically these have moved in line. But no longer.

This gap between world growth and the growth in our export markets is a major reason why it is so difficult to get the UK to grow. World growth is orientated to China and the Far East but our exports are still orientated towards Europe, even if the EU share has now slipped to just below 50%. World growth keeps up the price of commodities, raw materials, energy and food. This pushes up the cost of living and squeezes disposable incomes, leading to lower consumer growth. Sluggish growth in UK export markets means that even after a major devaluation, we are failing to grow our exports fast enough to offset the impact of squeezed disposable incomes.

Our forecasts show that the gap between world GDP growth and GDP growth weighted by UK exports in 2011 will persist. The UK will have to change the pattern of its exports to reflect the pattern of world economic growth if we are to stand any chance of matching world GDP growth.

This reinforces the point I have made in previous lectures that the UK really needs to take the fast growing economies seriously if we are to have any chance of achieving economic growth. The Prime Minister’s export promotion trip to India was a good idea and will hopefully help. But this highlights the urgent need for additional airport capacity.

We are unlikely to win much trade travelling on ‘A Slow Boat to China’!

© Professor Douglas McWilliams 2013

Part of:

This event was on Thu, 28 Feb 2013

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login