Britain in the 20th Century: The Attempt to Construct a Socialist Commonwealth, 1945-1951

Share

- Details

- Transcript

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

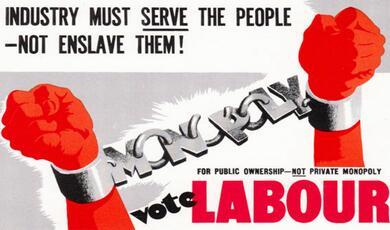

To the surprise of many, the 1945 general election led to the return of Britain’s first Labour majority government. Labour’s 1945 election manifesto declared that it was a socialist party and proud of it. The Attlee government created the modern welfare state and the National Health Service, and nationalized the public utilities. It sought to construct a New Jerusalem, a socialist commonwealth. Why did it not succeed in doing so?

This is a part of the lecture series Britain in the Twentieth Century: Progress and Decline. The other lectures in this series given during the 2011/12 academic year include the following:

The Character of the Post-War Period

The Conservative Reaction, 1951-1965

The Collapse of the Post-War Settlement, 1964-1979

Thatcherism, 1979-1990

A New Consensus? 1990-2001

Download Transcript

15 November 2011

Britain in The 20th Century:

The Attempt to Construct a

Socialist Common Wealth,

1945 - 1951

Professor Vernon Bogdanor

This lecture considers the post-war settlement put forward by the Attlee Government, which I began talking about in my last lecture. I discussed, in particular, the Welfare State, which was instituted by the Attlee Government, completing reforms of earlier governments: the Liberals, before the First World War, and then the wartime Coalition. I now want to discuss the other elements of the settlement.

The second element was a belief in planning, which was a great contrast to the end of the First World War, when planning and nationalisation had rapidly been succeeded by de-control. The Labour Party, in its 1945 Manifesto, called “Let us Face the Future”, said that it would plan “from the ground up”. Herbert Morrison, Leader of the House of Commons, said in 1946 that, “planning, as it is now taking shape in this country under our eyes, is something new and constructively revolutionary, which will be regarded in times to come as a contribution to civilisation as vital and distinctively British as parliamentary democracy and the rule of law.”

But what did planning mean? During the War, of course, goods had been allocated by a policy of rationing, which is what some members of the Labour Party believed in by “planning”. One economic advisor wrote in his diary: “I fear that Cripps [Sir Stafford Cripps, President of the Board of Trade and then Chancellor in the Labour Government] wants a detailed economic plan in the sense of a statement of exactly how many shirts, how many pairs of boots and shoes, etc., we should produce over each of the next five years. This, I believe, if taken seriously, would lead to the sacrifice of all the flexibility which a proper use of the pricing and cost system demands.”

All that, obviously, would have meant an end to the idea of consumer sovereignty and might even have involved directional labour, which would have been unacceptable to the trade unions. As a result, the Labour Party moved away from the rather unrealistic idea of retaining rationing as a permanent system; they said that they would keep controls in place to primarily deal with shortages, particularly food shortages, and that these controls would end when the shortages ended. That meant the Labour Government began a process, in the late 1940s, of de-control, which was accelerated by the Conservatives when they came to office in 1951. Broadly speaking, the Conservatives developed the view that it was better to return to the market. In 1949, Harold Wilson, as President of the Board of Trade, announced what he called a “bonfire of controls”, getting rid of many licensing arrangements for the building trade and other controls. Rationing was not finally ended until the early 1950s.

Of course, by “planning”, Labour did not simply mean the continuation of wartime controls and rationing. So, what did it mean? It did not mean an industrial strategy of the kind that the French would have and Japan had – that is, control of industry by the state. There was no real long-term policy for industry, no investment policy and no real idea of what to do with the nationalised industries. You may say that it was difficult to achieve that when the trade unions were such an important part of the Labour Party.

In practice, the Labour Government came to concern itself much more with the stabilisation of the economy, rather than with problems of planning industrial structure. Harold Wilson said that the great gap in the Labour Party’s policy at that time was a real policy for private industry. It was going to nationalise certain industries, a subject I shall come to in a moment, but it had no real policy for planning the private sector. You may criticise the Government of that time for evading all sorts of difficult questions about Britain’s industrial efficiency, which would become important later on. Indeed, planning, unlike the Welfare State, did not last for the whole of the post-war period. You could argue that planning and the role of the state are the main victims of post-war politics, coming to a sudden juddering halt in 1979, when Margaret Thatcher was elected. I do not think that any Party nowadays would use planning as a slogan. However, in the immediate post-war period, it was important.

As I said, the trade unions played a fundamental part in the Labour Party. The great trade union leader of the inter-war years, Ernest Bevin, was Foreign Secretary and, in practice, the second most important person in the Government. In some ways, he was even more important than the Prime Minister.

As part of the wartime Government, Bevin had been Minister for Labour and National Service, from 1940 to 1945. When he entered the ministry in 1940, he commented, “They say that Gladstone was at the Treasury from 1860 to 1930. I’m going to be Minister of Labour from 1940 to 1990.” What he meant by that was that the labour movement, organised labour, should be regarded as an equal partner with employers and other groups in discussions with Government; decisions about the trade unions and about working people should not be taken (as he believed they had been during the ‘20s and ‘30s) without discussions with, and indeed the consent of, the labour movement. Bevin believed the decisions which had led to the General Strike, in which he played a prominent part, had occurred because labour was not treated as an estate of the realm of particular importance. After the General Strike, Bevin came to the view that it was no good trying to resist the capitalist state, but it was better to try and get an established and recognised position of partnership with it.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the trade unions were gradually accommodating themselves to the capitalist state rather than resisting it. This process was symbolised in the ‘30s when the secretary of the trade union movement, Walter Citrine, accepted a knighthood from the National Government. This showed that the trade unions were partners in the state and recognised by the state. This idea was strengthened by the rise of the dictators in the 1930s, when even the most left-wing trade union leaders came to accept that the capitalist state was worth defending against external enemies. Indeed, the trade unions were vocal in pressing for greater rearmament to defend the country.

One of the reasons that Neville Chamberlain failed, in 1940, to continue in Government was that he could not get the support of the Labour Party or the trade unions, and so the trade unions obviously became very fundamental with a Labour Government. During the period of the Labour Government, from 1948 to 1950, you have got the first, and perhaps only really successful, voluntary incomes policy, whereby the trade unions agreed not to use their bargaining power to the full, but to accept wage restraint. This was because they believed that the other policies of the Labour Government were leading to social justice and it was a fair society, and in that fair society, the unions ought to make their contribution. The wages policy broke down following the Korean War, which led to inflation, but it might have broken down anyway.

“I want to be Minister of Labour till 1990,” said Bevin. Well, he was Minister of Labour until the Winter of Discontent of 1978/9, because Bevin’s policies - that the TUC should be consulted on all major issues of policy - were accepted not only by Labour governments but by Conservative governments; the Governments of Churchill and Macmillan, as much as the Government of Attlee. The TUC became an estate of the realm. You might argue that they took things too far, leading to the Winter of Discontent, and Margaret Thatcher was the first Prime Minister to adopt policies the trade unions did not like, without consulting with them. That ended, as it were, Bevin’s period in the Ministry of Labour. The whole idea of collective solidarity gradually broke down after the War. Perhaps it could not be preserved, perhaps it was something unique to wartime, not easily reproduced in the peacetime era.

When later Governments attempted to impose incomes policies, they could not do so with the ease of the Attlee Government’s first incomes policy. The need to impose an incomes policy was a consequence of full employment, because it increased trade union bargaining power enormously. It was thought, at least until Margaret Thatcher came to power, that governments could not run an economy that would increase unemployment. It was thought that this would lead to electoral defeat, because of people’s memories of the 1930s. They thought, with new Keynesian techniques, that you could avoid unemployment, but this meant that one of the constraints on union power had disappeared. You had to find a substitute. Until Thatcher appeared, that substitute was seen in some form of incomes policy. The argument was, which Bevin accepted, that, in return for the unions being given such an important role in Government, they ought to cooperate with Government and restrain their use of bargaining power in the general interest.

Now, that idea had one flaw, which was pointed out by one very prescient trade unionist as early as 1950, and his words provide a key to what happened in the Winter of Discontent. He said: “We were not meant to be public servants, to guard the interests of the nation. We were appointed to protect our members and to further their interests within the framework of the law. Does anyone ask the employer to have the national interest in mind instead of the interest of his firm? It’s alright having the national interest in mind, but we are not the right people to have it.”

This was a great problem for a party of the left. The Labour Party was often seen as radical, but the powerful trade union element in it suggests an alternative view, that the Party was a rather defensive and conservative movement, with a vested interest in preserving the traditional practices of the trade unions. Margaret Thatcher was later to undermine or radicalise those practices because they were seen not to be compatible with industrial efficiency.

Until Margaret Thatcher, there was a continuation of policies originating before the First World War, and even through the much criticised National Governments of the ‘20s and ‘30s that followed it, where the emphasis was always on conciliating labour, trying to bring them into the system, trying to weaken the power of class conflict and class war. However, Thatcher would have argued that we paid too high a price for being so successful in containing social conflict. She would say these were policies of appeasement and that we paid a high price in the loss of industrial efficiency.

It is fair to say that, in the Attlee Government, this conflict was not there. It was remarkably successful, both in increasing economic growth and industrial efficiency, and in establishing a very good relationship with the trade union movement.

So, those are two further elements of the post-war settlement, in addition to the Welfare State: planning, and the relationships with the trade unions as an estate of the realm.

I now come to what you may consider to be the main element of the settlement, which no government has dared to touch in any fundamental way since it was set up - namely, the National Health Service, which passed as legislation in 1946, and came into effect in 1948.

This was prefigured by the Coalition Government, which issued a White Paper calling for a National Health Service in 1944, and it is fair to say that a National Health Service was a common ground between the parties. However, the Coalition Government’s proposal was for a much less comprehensive service than the one put forward by Aneurin Bevan, because it argued for a National Health Service under local authorities.

Before the War, there was already in existence a rather haphazard patchwork of municipal hospitals, run by some local authorities but not others. There were also voluntary hospitals, which were fee-paying. When you went to one of these, you were asked if you could contribute. Of course, some people could not contribute. There is a rather unfortunate anecdote of one lady who came in, expecting a baby, and was asked if she could contribute. She said that she could not, because she needed all her resources to pay for the baby. When the baby was stillborn, she was told, “Well, you won’t need that money now – can you give it to the hospital?”

The Labour Party was proposing a much more comprehensive national system, but maybe surprisingly, the main hostility to it came not so much from the Conservatives as from the British Medical Association - from the doctors. Doctors are now resisting reform of the Health Service; they have resisted every change in the Health Service since it was set up, but they also resisted the Health Service itself!

At the BMA House, they cheered the defeat of Beveridge for his seat on Berwick-on-Tweed in 1945. The former Secretary of the BMA, Dr Alfred Cox, said of Aneurin Bevan’s Bill: “I have examined the Bill and it looks to me uncommonly like the first step, and a big one, towards national socialism as practised in Germany. The medical service there was early put under the dictatorship of a “medical Führer.” This Bill will establish the Minister for Health in that capacity.”

There is an analogy with the fact that some people in America think Obama’s healthcare system to be a form of communism. It should also be said that, at that time, the BMA primarily represented the better-off doctors, who made considerable gains from the previous system, from contributions from patients.

The key elements of the Bevan system still remain. Firstly, it was universal - it would apply to every person in the country. You could opt out of it, but you did not need to opt in. Everyone would automatically be a member of it. Secondly, it was free at source. Thirdly, and this was the most important thing that Aneurin Bevan did, it nationalised the hospitals. The hospitals were no longer to be run by local authorities or voluntary bodies, but were nationalised and run from the centre. Bevan argued that local authorities were too small, the rates were insufficient to sustain a service and there would be too much inequality between rich and poor areas. What Bevan wanted was a national service, available to people in poor as well as in rich areas, without discrimination.

Bevan said, with some degree of hyperbole perhaps: “This is the biggest social experiment in the social services that the world has ever seen undertaken.”

It was the first health system in the world to offer free care to the whole population, and the first comprehensive system to be based not on the insurance principle, as the old Lloyd George system was, but on a national provision of services, available to all.

Bevan saw this as a first step towards building a socialist society, because it was to be funded by the taxpayer and by no other source. He also, incidentally, favoured not the Beveridge system but a non-contributory welfare system, because he could not see why the poor should contribute to welfare payments.

When the Health Service was set up, Attlee made a conciliatory speech in which he said that it owed something to those in all political parties. Nye Bevan then made a speech which got him into trouble, and probably cost the Labour Party votes, in which he reminded people that he had gone down the mines at the age of twelve as a result of Tory mine owners. He expressed great contempt for them and said that, to him, the Conservatives would always be “lower than vermin”, that famous phrase. He branded Toryism “organised spivery”. Well, this was not the consensual attitude with which Attlee hoped the Health Service would begin!

Bevan saw himself as the main representative of democratic socialism. Indeed, he was one of just two Cabinet Ministers in the Government who had not been in the Wartime Coalition, so he had not been part of the wartime consensus.

Nigel Lawson, later Tory Chancellor of the Exchequer, said that the National Health Service was “the nearest that Britain had to a religion”, that the British people had lost faith in God and other principles, but the National Health was believed in without any evidence.

However, it created problems from the beginning. Because it was free at source, demand for it, in theory, would be unlimited; if any good is free, we want as much of it as we can get. Health is an unlimited good, if you like. But of course, the funding for it was limited and other Ministers were competing with Health for their budgets. Now, they would ask themselves: why should the Health budget be unlimited when our budgets are being limited? Of course, the Treasury had to decide, amidst very limited funds of money, how much the Health Service should get compared with other services.

Bevan said, as a democratic socialist, that you could not do that, that the Health Service should depend on the demand for health, which is an unlimited good. If you had to spend more for it, that was just the price you needed to pay to cure people of their illnesses and you should not allow a pettifogging Treasury to interfere with it. This would lead to the crisis which rocked the Labour Government in 1951 and kept it divided for 13 years, when Bevan argued with the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Hugh Gaitskell, over a seemingly trivial issue: whether charges should be imposed for false teeth and spectacles. That is, as I say, a seemingly trivial issue, but as I shall try and show in a few minutes, it blew up the Labour Government.

The National Health Service was, then, the next element of the post-war settlement and, broadly, it has survived. It is still a universal service. Obviously, we pay for prescription charges and appliances and so on, but the core of it is free – you do not pay the doctor, you do not pay to stay in hospital and so on. No government of any colour has dared publicly to suggest that any of these features be altered, as they think that they would lose votes by it - whatever Nigel Lawson said.

Now, the next element of the settlement, which has not lasted, was the nationalisation of various public utilities. The Bank of England was the first to be nationalised, in 1946, later denationalised by another Labour Government, the Blair Government, in its first days in 1997. The mines were nationalised in 1947, together with electricity, gas and the railways, and then, briefly, iron and steel in 1951.

We now see nationalisation as part of an ideological choice, and it is certainly true that some people in the Labour Government did see it that way, but most, I think, did not. In fact, most people in the country did not see it this way, because none of these industries or organisations were under undiluted private control. All were subject to some measure of public control. Even the iron and steel industry was run, in the ‘30s, by a cartel. All of them were the subject of an inquiry or official report during the War, and most of them recognised that they should be nationalised, often by chairmen who were Conservatives. Substantial parts of many of them were already owned, some of them by local authorities. For example, a lot of transport and many gas undertakings were run by local authorities. Electricity was 60% publicly owned. A quarter of bus and coach services were under local authorities. So, it did not seem like a huge ideological shift, as it may appear to us today. There were no real examples of unadulterated pure enterprise. The issue, to most people, did not seem one of public versus private ownership, but one of public ownership versus public control. When the Conservatives de-nationalised iron and steel in the ‘50s, they did not privatise it, as Margaret Thatcher privatised; they established it under a public cartel, so that it was not fully denationalised and there was still control and planning over the industry. It was seen as a practical solution, at that time, which convinced many people who were not themselves socialists.

However, in all this, there is a very important and crucial change occurring in the Labour Party. The original idea or programme of the Labour Party had been that nationalisation was somehow an end in itself, a part of achieving the socialist goal of a society based on fellowship. But now, it was becoming a means to an end, to be justified by whether it increased or decreased the efficiency of business or industry. You may consider it a practical, pragmatic question: if you find it does not increase efficiency, there is no argument for nationalisation. This was a very different sort of position from the original socialist position, marking movement from socialism to social democracy.

Labour was gradually moving away from a commitment to wholesale nationalisation. In 1949, it issued a policy statement called “Labour Believes in Britain”, in which it said that nationalisation was appropriate where private enterprise was “failing the nation.” Of course, this meant that where private enterprise was successful, you did not need nationalisation. In 1950 and 1951, there were very few new candidates for nationalisation. Nationalisation was no longer at the centre of labour policy in a way which it was in 1945.

Nationalisation is the final element of the settlement which I want to mention. It has not, of course, lasted, and the so-called mixed economy lasted until Margaret Thatcher, and then she privatised everything. In 1997, when Tony Blair came to power, the question was not what Labour would nationalise but what it would privatise; the Labour Party actually went further in privatisation after 1997 than Margaret Thatcher. So, nationalisation, that part of the settlement, is dead.

I want to sum up the achievements of this Government before coming to its demise, and its achievements were very considerable indeed.

Between 1945 and 1950, Britain increased her exports by 200% and brought her payments into balance. This was before the Korean War, which worsened the situation, but no one thought, in 1945, that this could be achieved so rapidly.

In contrast to the inter-war years, full employment was preserved. Unemployment was under 1% for the whole period of the Labour Government. If you look at the depressed areas, in the North-East, in 1938, unemployment had been 38%; in 1951, it was 1%; and by 1988, it was 13% again. It was going up and is, of course, higher now.

Output between 1945 and 1951 increased by a third. Real Gross Domestic Product rose by 3% per annum from 1947 to 1951, and that is the highest four year rise in GDP in the 20th Century.

Wage rates rose, on average, 6% a year, compared with prices, which rose by 4% or 5% a year, so there was a small increase in the standard of living each year. However, it was smaller than it need have been because so much of the increase in output was steered into investments and exports which the country needed. Therefore, it was not apparent to the ordinary consumer, who took the view that there was too much rationing and austerity.

You often read accounts of that period, which suggest that everything was very grey and that you could not buy any consumer goods. However, most of these accounts come from comfortable people of the middle classes, who could not buy the consumer goods that they wanted. For poorer people, it was not such a difficult time; rationing held down prices and so they were able to buy the essentials of life more easily than they could have done before. So, you have got to be careful from which side you look at it.

The middle classes were the key marginal voters under our electoral system, and that was where Labour lost seats in 1950 and 1951. These were the seats that they had gained in great number in 1945, particularly in the suburban areas of London and Birmingham, and those were the areas which swung heavily against Labour in the early ‘50s. The working class vote, on the other hand, increased: Labour got a higher vote from the working classes in 1950 and 1951 than it had in 1945. This is why it lost the election of 1951, despite getting more votes than the Conservatives, because it piled up huge majorities in working class areas, where they were not needed, but lost the key marginal seats.

On the whole, the Labour Government was very successful economically. You might argue that the greatest social advances of this century were the National Insurance Act, the National Assistance Act and the National Health Service. Social welfare was now based not on charity but on individual rights and maintaining civilised living standards for millions of people. The school leaving age was raised to fifteen, which was another fundamental achievement. Labour successfully reduced insecurity and achieved one of its fundamental aims as a party, the universal minimum for everyone.

A social investigator, Seebohm Rowntree, studied poverty in York over the course of the 20th Century. In 1936, he found that 31% of the working class lived in poverty; by 1950, the figure was down to 3%. That was not only due to welfare but to high wages, as a result of trade union bargaining power and, above all, full employment. Rowntree found that, in 1936, unemployment was the cause of poverty in 29% of cases, and low wages in 33% of cases; in 1950, the figures were 0%, because of full employment, and 1% due to low wages. Rowntree said that the remaining poverty seemed primarily caused by sickness and old age and he thought, very optimistically, that the advance of the Health Service and increases in pensions could deal with that. It was a very optimistic period.

The Labour Party had also been very successful abroad. It instituted policies of collective security, through the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, and with America played a part in resisting what it saw as aggression in Korea. It de-colonised India - some said much too rapidly, but at least it avoided the long, drawn-out and hopeless battles that the French fought in Algeria or the Belgians fought in the Congo. The Labour Party’s policies in India were summed up by the Chancellor Hugh Dalton, in a diary entry of 1947: “If you are in a place where you are not wanted, and where you have not got the force to squash those who don’t want you, the only thing to do is to come out. This very simple truth will, I think, have to be applied to other places too – e.g. Palestine. I don’t believe that one person in 100,000 in the country cares tuppence about it, so long as British people are not being mauled about.”

I think that was a fair estimate.

However, and as you would expect, it was not a wholly one-sided record of success. There were failures. The first failure which damaged the Labour Party very considerably was a coal crisis in 1947, when, at a day’s notice, all electricity had to be cut off in the South-East of England for 24 hours. As the Food Minister was Strachey, and the Minister of Fuel and Power was Shinwell, the motto came to be: “Starve with Strachey, shiver with Shinwell!”

Furthermore, the Labour Party did not have an effective policy to meet the shortage of dollars, which had not been seen clearly before 1945. There were periodic economic crises with dollars leaving the country.

Also, the Labour Party did not manage to do much about the Palestine problem, though you may say not particularly to its discredit since no one else has been able to do anything about it either!

Some people argued that too much of national output went into exports and capital formation and that it was asking too much of the electorate; they should have increased consumption more. In response to that, Attlee would have stressed a Thatcherite belief in Victorian values of saving and thrift, rather than consumption. He said that there was “a national effort which all ought to be involved with to get the economy back on its feet”.

Attlee chose his Ministers poorly. He kept elderly dugouts in Government much longer than they should have been when he should have been ushering in the young. In my opinion, he should have promoted Aneurin Bevan, whom he thought should be his successor.

One of the problems that hit the Labour Government, and indeed broke it up, was rearmament following the Korean War. That was when heavy expenditure occurred, which did the most damage to the prospects of British industrial recovery in the 1950s, because it compromised the export drive just when Germany and Japan were returning to world markets. They were not involved in heavy rearmament, for obvious reasons.

Of course, people in that Government had memories of appeasement in the 1930s, and they thought it would be very dangerous to appease Stalin in Korea, much as it had been dangerous to appease Hitler. As a result, they thought they had to take part in rearmament.

Nevertheless, this was a new and very important settlement. The word “consensus” is often used, but I prefer the word “settlement” because so much of it has remained.

One aspect of the settlement that is not often noted is the effect it had on the Conservatives. Essentially, they could only get to power if they accepted the main elements of it. If they had supported traditional free market policies, if they had said they did not believe in the Health Service or the Welfare State, they would never have returned to Government.

There was nonetheless a breach with the traditional Labour view, that there were two forms of society - a capitalist society and a socialist society - and the aim of the Labour Party was to replace one with another. However, the obvious conclusion to be drawn from the Attlee Government was that capitalism could in fact be reformed.

In 1946, Anthony Crosland, one of the younger members of the Labour Party and who would become a Minister in the Wilson and Callaghan Governments, wrote an important book called The Future of Socialism. Crosland argued that Attlee’s reforms had so fundamentally reformed the capitalist system that socialism itself had to be revised; he said that: “Many liberal-minded people have now concluded that Keynes, plus modified capitalism, plus the Welfare State, works perfectly well.” I think you can see the roots of Blair’s New Labour in that statement, where Clause 4 was abolished and the Labour Party was no longer centrally concerned with state control. In effect, capitalism was saved by the Labour Governments, relying on the influence of Beveridge and Keynes, neither of whom were Labour – both were Liberal.

Some on the left, including Bevan, tended to attack the Labour Governments for saving capitalism. They believed we should have moved on to socialism. Oddly enough, no one on the right thanked Keynes and Beveridge for saving capitalism; indeed, people like Margaret Thatcher tended to attack Keynes.

So, this idea of fundamental alternatives no longer existed, creating a very different political battle. This was reflected in the 1950s by the phrase “Butskellism”, because the Conservative Chancellor of the Exchequer in the government that succeeded Attlee’s was R. A. Butler and the Labour Chancellor at the end of the Labour Government had been Hugh Gaitskell. People said there was a lot of agreement between them – hence Butskellism.

It is also worth noting that it was a highly centralising settlement. There was nothing about devolution or decentralisation or “the Big Society” because the Labour Party said only a strong central state could ensure equality and fair shares, and that benefits should be funded by central government. Bevan, although Welsh, strongly resisted the idea of separate Welsh or Scottish Health Services, and he would have hated devolution. He said: “Sheep don’t change their character when they cross the Welsh border... If you’re ill, the treatment you need doesn’t depend on whether you’re Welsh or Scottish or English, but the sort of treatment you need, how ill you are, depends on need and not on geography.”

As I say, the settlement was attacked very strongly from the left by Bevan (and later by Tony Benn) as a substitute for socialism, but the more fundamental attack came later on, from the right, and particularly from Margaret Thatcher.

Thatcher’s main criticism was that it was too concerned with fair distribution rather than with increasing production. She believed that the real problem facing Britain was how to make it more efficient and get rid of a sense of guilt attached to the “ruling classes.” She wanted to radically rid the country of outdated industrial methods, trade management, and so on.

That criticism is a bit unfair because the Labour Party did, as I have shown, succeed in increasing industrial production. The Party took the view that the Welfare State and the Health Service were valuable in themselves, but they could also give you a more effective population, one more capable of production and with less days lost through absenteeism.

However, it is fair to say that Labour did not entirely attack the restrictive practices and difficulties that plagued British industry. John Maynard Keynes summed the situation up in a memo to the Cabinet in March 1945, near the end of the War: “If, by some sad geographical slip, the American Air Force, which is too late now to hope for much from the enemy... were to destroy every factory in the North-East coast and Lancashire, at an hour when the directors were sitting there and no one else, we should have nothing to fear... How else we are to regain the exuberant inexperience which is necessary it seems for success, I cannot surmise.”

The problem was that, if they could not increase industrial efficiency, how were they going to pay for this wonderful Welfare State?

In 1951, Herbert Morrison, who was on the right of the Party, said there was “a tendency in education and the other social services for expenditure to rise from year to year, without full regard to the taxable capacity of the country to a greater extent than had happened in recent years. What was desirable must be judged in the light of what was practicable, from the point of view of long-term finance.”

Stafford Cripps, who was on the left, said they were “reaching the limit on expenditure which could be raised by taxation and there was a serious danger that obligations might be entered into which the country could not meet in future years.”

In 1949, the first little breach came in Nye Bevan’s Health Service because a bill was introduced making it possible to impose prescription charges. These were not actually imposed by Labour; they were imposed by the Conservative Government afterwards. Bevan accepted it, thinking that this would not be imposed as the Government was seemingly still moving towards socialism. The Chancellor, Sir Stanley Cripps argued that charges on prescriptions would simply be a response to abuse, to what Bevan himself called “the ceaseless cascade of medicine which is pouring down British throats”. In this light, you could argue that the intention of the bill was to protect the Health Service and not to raise revenue, keeping the principle of a free National Health Service preserved.

However, things changed. Cripps became very seriously ill and resigned in the autumn of 1950, to be replaced as Chancellor, much to Bevan’s chagrin, by the young Hugh Gaitskell, who had just entered Parliament in 1945. Bevan wrote a letter of protest to Attlee, complaining that Gaitskell had “no roots or experience in the labour movement”, that he was a middle class intellectual from Oxford who did not understand the trade unions, and it was a grave mistake to appoint such a person. In the spring of 1951, the Foreign Secretary, Ernest Bevin, died and was replaced by Herbert Morrison. This meant that the two major posts in the Government had gone, and Aneurin Bevan, who had great claim to either of them, got neither. Attlee did not treat him well.

Bevan would have been content with the position of Colonial Secretary, but Attlee said he could not put him in that position because he was too racially prejudiced – that is, Bevan was too pro-black and against the white settlers in Rhodesia and South Africa!

He was moved, in January 1951, to the post of Minister of Labour. This was a particularly sensitive position to be in because, with the problems arising from the Korean War, you would have to hold down wages in some way if you were going to be able to finance rearmament. This was perhaps not the position that should have been given to a leading figure in the Labour Party.

The new Minister of Health was Hilary Marquand, who was outside the Cabinet, meaning that Health was downgraded. The position of Bevan, opposed to the prescription charges, was made difficult because Hilary Marquand agreed to the charges; Gaitskell and the Government could say to Bevan that if the Minister of Health agrees to the charges, who was he to oppose them?

Hugh Gaitskell was determined that the anomalous position, as he saw it, of Health, whereby it was the only service where expenditure was unlimited, should stop. Unlike Cripps, he was not prepared to tolerate Bevan wanting as much spent on the Health Service as people demanded, so he was in favour of a ceiling of expenditure.

In Bevan’s case, he was not prepared to accept from Gaitskell what he had been prepared to accept from Cripps, because he did not regard Gaitskell as a socialist. Gaitskell proposed many things, which, perhaps fortunately for him, were never made public. The records tell us that he proposed a charge for a stay in hospital in 1951. This was rejected, but it was a proposal that not even Margaret Thatcher put forward. Beveridge, incidentally, was in favour of hospital charges, on the grounds that it should not be more profitable for a patient to be in hospital when he could be at home – a rather odd justification!

Gaitskell introduced a ceiling on the Health Service budget, which he said could only be achieved if charges were implemented for false teeth and spectacles.

The basis of Bevan’s belief in a free Health Service was his faith that people could be trusted to be responsible. From that point of view, charges would not be necessary because increases in expenditure were merely temporary, a backlog caused by bad treatment before the Health Service existed. It was true that a lot of people with serious complaints, particularly women, who had not been covered by the Lloyd George insurance scheme, had not gone to the doctor because they could not afford to do so. As soon as this backlog was cleared, Bevan argued, spending would fall. On this point, he was also correct. The Conservatives established a committee in the 1950s to look at overspending in the Health Service, and it concluded that it was not overspending; the Health Service budget was actually being contained.

In the Cabinet, Bevan argued that the rearmament programme was too large and could not possibly be met, because the raw materials would not be forthcoming. On that point, he was proved correct, and the Conservative Government that succeeded Labour, led by Churchill, scaled down the rearmament programme. Gaitskell, however, was keen for Britain to do all it could in rearmament because he wanted to keep the Americans on-side. There was a great fear that the Americans would withdraw from Europe if other countries did not make their contribution.

Fundamentally, Bevan was beginning to take the view that the Government was going in the wrong direction. Previously, for all its difficulties and setbacks, it had been moving forward towards some form of socialism, however you define it, confirmed in his mind by the principles of Cripps and Attlee. Now, however, he thought it was going in the wrong direction, coming under the influence of middle class economists that could not achieve anything more. Bevan resigned from the Government, with Harold Wilson, another Cabinet Minister, in May 1951, taking the view that there was nothing to be gained by remaining in office on that basis.

Bevan’s resignation marked the end of his dream that post-war Britain could move towards a socialist society, like that of Sweden or Norway. He now saw socialism as a lost battle, because the solidarity of the working classes had been eroded by affluence and individualism; in the late-1950s, he attacked what he called “the affluent society”. He said, “Our people have achieved material prosperity in excess of their moral stature.” In 1959, he said to a colleague, “History gave [the working class] the chance... They didn’t take it. Now, it is probably too late.”

Neither Bevan nor Gaitskell held office again; both died prematurely, Bevan in 1960 and Gaitskell in 1963. Many years later, Gaitskell’s widow told a journalist and friend of Bevan that Bevan should have been Leader, as, “He was a natural leader for a socialist party.” Of course, this raises the question of whether Labour was, or was still, a socialist party. In any case, it ended that particular dream.

The left saw 1945, and in particular the establishment of the National Health Service, as the beginning of a period of socialist advance. The Marxist historian, Eric Hobsbawm, was very fond of writing about “the forward march of labour”. However, with hindsight, it is more accurate to see the Attlee Government as a culmination, rather than a beginning. After Attlee, the country moved in a very different direction. Margaret Thatcher in particular, the first Prime Minister to grow up in the post-war period, asked whether Britain could really afford traditional institutions and habits inherited from the Attlee Government. Perhaps the Welfare State worked in the past, but was it still needed in an affluent society? The settlement broke down, with an attack from the right, which was very important.

The left, therefore, was disappointed by the 1950s and what happened afterwards, but in a sense, the Conservatives were also disappointed. I shall now explain why.

Churchill succeeded Neville Chamberlain as Leader of the Conservative Party in October 1940 – he had become Prime Minister in May, but Chamberlain remained Leader until terminal illness forced him to retire. Churchill asked himself whether he was able to sincerely identify himself with the main historical conceptions of Toryism. The answer was yes, “since at all times, I have faithfully served two causes which I think stand supreme”. These two causes were “the maintenance of the enduring greatness of Britain and her empire and the historical continuity of her island life”. For Churchill, the essence of Conservatism was that Britain should remain a great power – part of what became known, at the end of the War, as “the Big Three”.

While Attlee did not agree with this view, Ernest Bevin - the Foreign Secretary in the Labour Government – did. It was Ernest Bevin who pressed hardest for Britain to become an atomic power, not so much because of Russia, but to stand up to America. He said, “We could not afford to acquiesce in an American monopoly of this new development” – it was a symbol of independence. The Chancellor and the President of the Board of Trade worried about the cost, but Bevin was adamant that Britain had to have it, whatever the cost - “We’ve got to have a bloody Union Jack flying on top of it!” Attlee rather finagled the final decision, because the key committee excluded the economics ministers who said Britain could not afford it. Cabinet and Parliament were not told – talk about Prime Ministerial behaviour! The decision was eventually exposed following a parliamentary question on the defence estimates, which listed one of the items of expenditure as British atomic weapons. When Attlee was asked, later in life, why he did not tell his Cabinet colleagues, he said that some of them were not fit to be trusted with matters of that sort! Attlee said the most important thing Bevin did was stand up to the Americans.

The second thing that Attlee did, and Churchill followed suit, was to resist American pressure to become part of a super-national Europe. The Americans said that they could not afford to endlessly pay for Europe to defend herself, and that it was time Europe defended herself on her own. They said that you could not achieve this with squabbling countries. The best solution would be for European countries to join together in a federation, to rearm and form collective security so that the American burden would be lightened. This was something that neither Bevin nor Churchill wanted to do.

In 1952, Anthony Eden, Foreign Secretary for the Churchill Government, made an important statement in America. He warned the Americans against trying to push a country to act against its basic instincts: “You will realise I am talking about repeated suggestions that Britain should join a federation on the Continent of Europe... This is something we all know in our bones we could never do.” You may consider this profound or be backward-looking, but it was the view of the Conservative Government at the time. Eden said to one of his advisors in the Foreign Office, “The letters I get from constituents [in Warwickshire] ... They’re all from people in Canada, Australia, New Zealand. They are the people who are closest – that’s where their relatives are... The Continent is where their ancestors are buried – that’s what they think of the Continent…they don’t want to be involved with Europe.”

We did not succeed in becoming one of the “Big Three”. Did we do badly in the post-war period because we tried to do too much?

One of the scientific advisors to the Labour Government, Sir Henry Tizard, said, in 1949: “We persist in regarding ourselves as a great power, capable of everything, and only temporarily handicapped by economic difficulties. [But] we are not a great power and never will be again. We are a great nation, but if we continue to behave like a great power, we shall soon cease to be a great nation. Let us take warning from the fate of great powers of the past and not burst ourselves with pride – see Aesop’s fable of the frog.”

The Conservatives desperately struggled to combat the decline of Britain as a great power, but it is fair to say that they did not succeed. The Conservatives played as much of a role as the Labour Party in liquidating the Empire and ending Britain’s role as a great power.

Perhaps Churchill, in a way, instinctively understood this. In 1946, when he visited America, he said to the President, Harry Truman: “If I could be born again, I’d like to have been an American. America is the country of the future. Britain is the country of the past. It used to be said that the sun never sets on the British Empire, but countries rise and fall. America is now the land of opportunity.”

At the end of his life, Churchill said he was depressed because, “I worked hard all my life and I have achieved a lot, but I have achieved nothing.” Churchill hoped that the strong and secure British Empire would be a guarantor of peace in the world. He said he would not be regarded very highly by history: “statesmen are judged not by their victories but by what they did with their victories... I could have defended the British Empire against anybody, except the British people.” This was another failure of a dream.

Churchill succeeded the Labour Government in 1951, though he had always said that he would retire at the end of the War. He had said that he would not make Lloyd George’s mistake of hanging on; speaking to Anthony Eden, his heir-apparent, in the Cabinet Room at the end of the War, he said, “Thirty years of my life have been passed in this room – I shall never sit in it again. You will, but I shall not.” But of course, he did return, though it seemed that nothing he did could add to the reputation he had gained in 1945.

His peacetime Government was, of course, very different from the Wartime Coalition. On the whole, Churchill was unfit to remain as Prime Minister. The public had not been told that, since the War, he had suffered very serious heart attacks and strokes; he was a very ill man. The French President, Auriol, who visited Britain in December 1951, reported that Churchill was “a man whose hearing is poor and who often repeats himself”. In 1954, the French Ambassador reported to his Government: “He is still active only in appearance.” In May 1953, shortly before suffering a very serious stroke, which made people think he would not survive the weekend, an aide to Dr Adenauer, the German Chancellor, wrote in his diary: “Churchill sometimes gives an uninformed, absentminded impression, and when he wakes from his dreams and poses questions, they are often off the point. The old man sits heavily in his chair. His left eye waters, and if he tries to give a connected opinion, such as on the British desire for peace, he seems, as often with old men, on the edge of tears. It is hardly credible that this man, despite his physical condition, should lead the British Empire. The Chancellor sometimes gets a poor impression from his interlocutor’s mistakes and makes notes of his concern on a piece of paper which he pushes over to me.”

However, the Permanent Secretary of the Foreign Office comforted Adenauer by saying the Foreign Office kept a constant eye on the Prime Minister.

Churchill was unfit for office, but there is a paradox. It is arguable that the 1951 to 1955 Government was one of the most successful in the post-war period, which perhaps shows the comparative unimportance of the role of a Prime Minister in British Government! Some people say Churchill saved Britain twice: firstly by action in 1940; and secondly by inaction in 1951, when he kept us out of the European Coal and Steel Community. I shall consider that in more detail in my next lecture.

Thank you.

© Professor Vernon Bogdanor 2011

Part of:

This event was on Tue, 15 Nov 2011

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login