Depression: Reality and Myth

Share

- Details

- Transcript

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

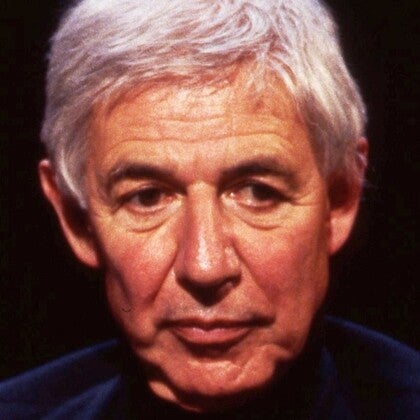

Professor Lewis Wolpert CBE FRS, Professor of Biology as Applied to Medicine, University College London Professor Raj Persaud Chaired by Professor Frank Cox, The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, past Gresham Professor of Physic.

Download Transcript

DEPRESSION: REALITY AND MYTH

Professor Lewis Wolpert, Professor Raj Persaud

and Professor Frank Cox

We’re had lectures, we’ve had discussions after the lectures, we’ve had one to one discussion with several people, but this is the first time we have had a one to one with two people who are not involved in actually giving the lectures.

Depression is probably one of the oldest known medical conditions. Descriptions of it date back to the very earliest writing, both the medical literature and of course the plays and poems and writings of very, very early peoples. I think the word depression actually crept in at about the time that Thomas Gresham was building this College, somewhere in the middle of the 16 th Century, and since that time it has been well known to us. It came as a great surprise to me as I was reading through my weekly morbidity and mortality reports for the World Health Organisation, my own particular interest in the causes and spread of disease, to realise how important depression was. It is in fact the fourth largest cause of long term disability worldwide, which is quite a great surprise to me. So we have an ancient disease, and we have a well known disease. Yet so little is known about it, that if you wander into any library, there are 20 or 30 books all saying completely different things.

So we are taking this opportunity to take two people who know a lot about depression to talk in fairly general terms. We don’t quite know how it’s going to go, but the two speakers of course are well known from a variety of different purposes. They are distinguished scientists in their own right, and distinguished clinicians. Raj Persaud, first of all. Raj is the Director of the Public Engagement Unit at the Institute of Psychiatry, which is part of King’s College London now, and he is also Visiting Professor for the Public Understanding of Psychiatry at Gresham College. Lewis Wolpert is Professor of Biology as Applied to Medicine – Emeritus Professor, as he points out to me. We were colleagues at one stage, so he’s not allowed to tell me that, at University College London, and has received a CBE and that was for his work on the public understanding of science. So these are two people who are very good communicators. Both of them are known through their writings in columns, in books... well you name it! Both are known on the television and the radio, so I think we are probably in for a rather good evening.

Now, I don’t know how this evening is going to progress, but what I do know is that in about half an hour’s time, we’ll move away from this end of the table and start engaging the various people who are sitting around the room. What I’ll do is start off by trying to find out exactly what we’re talking about - what we understand by depression. Could I ask you, Raj, first of all, if you could tell us what you think depression is?

Professor Raj Persuad (RP)

Thank you very much. First of all, can I just say how pleased I am to be here, and in particular to be here with Lewis, because when I was at medical school (Lewis will be embarrassed for me to say this) some 20 odd years ago, I spent most of my time at medical school studiously avoiding the medical school lectures. For example, I went to life drawing at the Slade instead, and I completed the Sociology of Law course, and this may have contributed to me failing Anatomy in the first year, but Lewis’ lecture was actually one of the few of the medical school lectures I attended, so that tells you the esteem in which I held his teachings.

I’m going to say a few perhaps provocative things about depression straight away. It actually isn’t really clear what depression is, but for something that it’s not clear what it is, we do know that it is pretty common. The statistics suggest that between one in four of us will get a depressive illness of a serious enough nature to warrant a formal clinical psychiatric diagnosis at some time in our lives. The latest epidemiological survey from the USA, and a lot of people dismiss it because they say, well, that’s Americans for you, but the latest survey from the USA suggests that one in two people at some time in their lives will develop some kind of psychiatric illness, i.e. symptoms severe enough to warrant a formal clinical diagnosis, and since most psychiatric illnesses are linked in some way to depression, and depression forms part of them, then we’re dealing with something that’s very common indeed.

The World Health Organisation has predicted that by the year 2020, which isn’t that far away, depression will account for the second biggest cause of disability worldwide, and that gives a clue that not only is this something that’s very common, but some people believe it’s getting more and more common, which is a bit of a puzzle, particularly in the western world, if it is the case it’s getting more and more common, given how our lives are meant to be getting better in the western world. We’re wealthier than ever before, we have more technology, we have more control over lives. We have more control over fertility, for example, and more control over disease, so given this general sense that our lives are meant to be getting better, why is it there’s some statistical evidence that depression is getting worse?

Maybe the answer to that question comes back to the question of what it is, and as I said before, it’s not clear what it is. Let me start by answering that question by saying something which is going to sound really kind of strange for a doctor that works on a daily basis in the National Health Service, but a lot of people say depression is a disease. Well, I’m not convinced that diseases really exist in the sense that doctors often think they do, which may sound like a really strange thing for me to say. Most people, when they think of a disease, they think of some biological abnormality. A classic thing is you go into Casualty with crushing central chest pain, they do an ECG, they look at the ECG and they see some abnormalities on the test, and they say you’re having angina or you’re having a heart attack. That’s the classic paradigmatic view of what a disease is.

Well, I have several problems with that. Let’s take a couple of examples. Let’s take IQ. You measure intelligence in the population, and the average IQ score is around 100, and someone who has a score of 150, which is somewhat at the genius level, is as abnormal as someone with a score of 50. They’re equally abnormal in terms of both ends of the normal distribution, and yet, the person with an IQ of 50, who will be classified as learning disabled, will attract quite a lot of medical services who will try to help that person, while the person with an IQ of 150 attracts no medical services that will try to reduce his IQ down to 100! Well, why is that? After all, the IQ of 150 is as abnormal as the IQ of 50. Here’s the key point: for me, the point is not how abnormal you are, as determining whether you attract a diagnostic label, but how undesirable or desirable your state of being is deemed. We deem an IQ of 150 as fairly desirable and an IQ of 50 as undesirable, and actually, it’s the desirability of a state that determines our sense of whether it will attract a disease label.

Here’s another example: the menopause. The menopause is a completely normal biological event. Every woman will go through the menopause, and as a result of the menopause, they will attract certain quite problematic medical symptoms, like osteoporosis, brittle bones, and a whole host of other things. There are treatments available now for the menopause. Why are we treating something that is biologically normal? Well, I think we’re right to treat something that is biologically normal because to me the issue isn’t whether something is normal or abnormal, it’s whether it’s desirable, whether it leads to suffering. If it leads to suffering and we can do something about it, we can use medical technology to do something about it, then we should. That to me is the basic criterion of a disease. Is it undesirable, does it lead to suffering, and can doctors do something about it? I think if you use those criteria, then depression is a disease, for want of a better word, depression is something that doctors should be involved in. However, it’s important to understand there is no blood test for depression, there is no inherent biological abnormality that’s been discovered yet. We’re doing a lot of research and we are finding some group differences between depressives and non-depressives, but there isn’t a difference that’s so clear and obvious that we can do a blood test and make the diagnosis that way. Because there is no blood test, if you go back to my view of what a disease is, which is something that causes suffering and something doctors can do something about, you can see that the boundary around what depression is gets kind of fuzzy, and therefore it’s not a clear diagnostic entity in the same way maybe that people can determine through reading an ECG.

So one of the questions is, is it useful to think of it as a disease? Is it perhaps disempowering? Does it mean that people say, “Well, I’ve got a disease, I need to go to the doctor, and they’re going to give me a tablet,” and that’s the way forward, because that’s the way forward if you have a heart condition? Might it be more empowering for us to think of it as something that we can do something about? We should collaborate with doctors, but maybe, if people were more self-empowered about what they might do about depression, maybe think about preventing depression, might that not be a more helpful way forward? So maybe the medical model has some certain inherent disadvantages.

Professor Frank Cox (FC)

Thank you very much, Raj. Lewis, would you like to tell us what you think about depression?

Professor Lewis Wolpert (LW)

Well, my interest in depression is that I’m a depressive. Up till the age of 65, I belonged to what I wittily called the Sock School of Psychiatry. You felt a bit low, you weren’t doing too well, you’d pull up your socks and get on with it! That’s empowerment, Raj! But I had a very severe depression, and I was very suicidal – I can take you through the thing. I am a hypochondriac. I had a problem with my heart, I was changing drugs. I got very bad, and one night – I was on an anti-depressant - but then one night, I had bad dreams, woke up the next morning with an overwhelming wish to kill myself, so they hospitalised me, and so that was my introduction to depression. I didn’t know much about depression, and when I came out and when I recovered – we can talk about treatment a little later on.

Raj, really, it’s quite clear that you’ve never been depressed. Just let me tell you something, and I cannot say it strongly enough: if you can describe your depression, you haven’t had one. I challenge you to find me a single novel in English literature which has a good description of depression – il ne exist pas. Yes, William Styron has described his own depression in Darkness Visible, and some writers have, but just considering the number of people who are depressed, particularly including writers, one in ten, one in five, you would have thought novels would be full of descriptions! No, it’s indescribable. You enter a state – I talk to other depressives. There’s the whole question of stigma, which we’re not going to get into, but because I’m public about my depression, I speak to a lot of depressives. We understand each other perfectly, in the sense we can’t describe how terrible it is, and it has all sorts of aspects. I mean, I have an young ex-student who is a self-harmer, which is a major problem, and she ends up in hospital every now and then, because at nights she self-harms. That’s the only way she can deal with her depression.

I really do think that you really must see it as a disease. It’s true that there’s no blood test, but there’s more to life than blood tests! It’s important to realise that there is a biological factor – it’s not just psychological. Can I just tell you, if you’ve got hepatitis, one of the drugs that they use is a drug called Alpha-Interferon. If you treat hepatitis with Alpha-Interferon, you’ve got to give the patient some anti-depressants at the same time. If you simply give them Alpha-Interferon, they will get severely depressed. So you can precipitate a depression purely biologically. Cushing Syndrome, in which there’s a high level of the hormone cortisol in the blood, can also precipitate a depression. So you can get depression from a purely biological basis without very little evidence of psychological aspects. I have a theory – an evolutionary model for depression, in which it’s sadness become extreme. But Raj is absolutely right, the diagnosis of depression, of being sad and then being clinically depressed, where that boundary is is a very, very tricky diagnostic thing. There is a list of things, whether you’re putting on weight, whether you’re losing weight, whether you’re suicidal – and by the way, there’s not much adaptable about depression. About one in ten of depressives will kill themselves, so you can see, it has very many negative aspects.

I think really, from my point of view, is that depression really is – and for someone – I’m on my anti-depressants at the moment, and in fact I’m just changing this week. I could bore you for hours about my own depression! I’m not too bad at the moment. The symptoms of depression, yes, there are those who are self-harming. My present condition, the thing is that I’m very sleepy during the day. You may say, oh well, that has nothing to do with depression, but it’s the mornings, and by the evening – there’s a daily rhythm to that, and that is usually, Raj I think you’d agree, a typical characteristic, that you’re bad in the mornings and getting better towards the evening, but next morning, you’re back, as it were, where you started. So for me, depression, I regret to say, is a serious disease.

I don’t think it’s very easy, and we’ll come to treatments later, for someone to do something about it on their own. They really need professional help. But that’s something we’ll come back to.

FC

Raj, do you want to come back on that?

RP

Yes. Well again, I don’t disagree with anything Lewis has said. It’s a very serious problem. I’m just quibbling a little bit about the use of the word disease, which I think can sometimes be unhelpful. It’s definitely a serious problem, it definitely causes a huge amount of suffering, and it’s definitely the case that doctors should be involved, alongside other professionals, in helping people with serious depression. One of the things that I’m really interested in is prevention, not just in treating depressed people, seriously depressed people, I have an in-patient unit and an out-patient unit at the Bethlem Royal in the Maudesley Hospital, so I actually see people who get so ill they get hospitalised with depression, and I see people who are suicidal as well, so definitely we’re dealing with a very serious problem, but we’ll come to treatment in a minute – treatment is problematic and difficult, but certainly possible. Therefore I’m interested in prevention. How do we prevent depression? Because I think we’re all vulnerable to it, it’s a very common problem and, given the right circumstances, any of us could end up being quite depressed. I’m interested in how do we prevent it, and that raises a very controversial question.

I wanted to ask you, Lewis, because you would have had I think some CBT (cognitive behavioural therapy), and one of the theories in psychology, and it’s just a theory I want to emphasise, is that there are some people who have certain personality predisposing factors towards depression. The classic words that we use in psychology and psychiatry are neurosis or neurotic people, and by neurosis or neurotic people, we mean people who worry a lot, for example, or who are prone to hyper-vigilance for danger or threat in the environment. I wondered, Lewis, if you could think about whether it’s possible that you’ve identified aspects of your personality or ways of thinking about the world that you think might have made you vulnerable to the depression, and whether those things are things that you’ve felt that, if you had known about before, it was possible, not that depression could have been prevented, but it might have been helpful to know about some of those issues before?

LW

The prevention of depression is a really very important issue, and I don’t have a clear thing. In my own case, I did say I’m a hypochondriac, and I do claim it was a drug that precipitated it – you know, they were changing drugs for my atria-fibrillation. I think that that’s what precipitated it, but it may have been psychological.

I think knowing about depression Is important. I think it’s monstrous that in schools children are told all sorts of things about health, but the illness that they’re most likely to come into contact with, namely depression, they’re taught absolutely nothing about. Whether it would help or not I don’t know, but at least they’d be aware of it and could get help sooner.

The other point that I forgot to mention, and which is related I think to whether you’re a depressive, and which is the most characteristic feature of depression, which we haven’t mentioned yet, is negativity. As you know, depressants are negative about everything, and that’s why, to put it bluntly, they’re such a pain in the arse! Nobody wants to be with a depressant, because they are negative about everything, totally self-involved and totally negative. So that’s one thing. I think it is something that, if someone realises that your partner or your friend or yourself are becoming increasingly negative, then maybe that is a diagnostic feature.

Whether you call it a disease or an illness – I never think of it as a disease, I always think of it rather as like an infection.

FC

I wonder if we could touch on a couple of things that both of you have raised? Lewis used the word sad, and Raj used the word serious. You’ve talked about this spectrum. We’re talking about one end of the spectrum, so is there in fact a whole spectrum there, from just being slightly unhappy and you can shake it off, that’s a pull up your own socks type of one, to one where obviously you need hospitalisation? Lewis?

LW

I have a theory, this is my theory which no one takes seriously. Funnily enough, I’ve written a book called Malignant Sadness. The point that I want to make is that my understanding of depression, and everybody agrees, and I think Raj will probably agree, is that a fundamental aspect of depression is it’s related to emotion, and particularly the emotion sadness. Freud – I’m very hostile to psychoanalysis, but Freud was very clear about and wrote a very nice piece about it pointing out how close it was to sadness. In my view, and I think it’s not unreasonable and it’s partly in the literature, depression is sadness become extreme. The trigger for depression in many, many cases is loss, loss of something. Sadness is a very positive, a very important, emotion. There is no human being in the world who cannot recognise a sad face. There’s been studies on that. You show them photographs of people with different expressions, and they recognise sadness immediately. It’s to communicate your sadness, and also, sadness makes you do something about a loss. When the mother goes out of the room and the child gets sad, it’s because it wants the mother to come back. Sadness is about loss of something. What has happened in depression is the sadness has become extreme.

We haven’t mentioned genes properly. It’s important. I really think there is a strong case you can make from looking at twin studies and so forth, that about half of your life, if you’ve had depression, about half of it is due to your genes. Please don’t take psychoanalysis seriously, and don’t go into psychoanalysis if you’re depressed! It’s the last thing you want to do, because that will depress you more! That’s the whole point surely.

If you are abused as a child, if you lose a parent as a child, yes, your likelihood of being depressed later on in life is certainly increased. Single women alone without social support are more likely to be depressed, and that’s universally. Twice as many women get depressed as men – it is not understood why. Maybe it’s because when women get depressed, they talk to their friends about it and ruminate about it. Men go out and play tennis and get drunk. We really don’t understand. Pre-adolescents, the ratio is one to one. Then there’s adolescence, and it becomes two to one. So I think that the key thing to focus on is sadness, and it’s that spectrum that I would go across.

FC

Would you agree with that, Raj?

RP

Yes. I think that there is a spectrum and, as I say, I’m really interested in catching the thing early and doing something

about it early, and I think there are so many things about the current approach to depression that are, frankly, scandalous in Britain today. The treatment that most people will get with depression is at such an abysmally low standard that it’s a national scandal. What you’ll get if you are depressed is you’ll go to your GP and the vast majority of people will simply get treatment from their GP. Now with all due respect to my GP colleagues, who, you know, are soldiering on in very difficult circumstances, that is not really going to be that helpful, for all sorts of reasons. Amongst other things, GPs haven’t really got the time to invest in the issue, they haven’t really had the training to correctly spot it and to work out what to do, and their classic approach is to prescribe an anti-depressant. A prescription of an anti-depressant is actually quite a complicated thing in terms of what you prescribe and what dose, and very often GPs don’t prescribe the right medication, and they often prescribe it at the wrong dose.

But the other thing that I still can’t get my head around is why if a woman goes to a GP and says, “I’m depressed,” and the GP asks why, and she says, “Well, my husband beats me up every night,” and he says, “Well, take this Prozac then,” I can’t understand how that’s really going to work. That, brutally simply, is the model that modern medicine is working with.

Fundamentally, people get depressed because they have – and here’s a technical term here – problems. They have problems of a rather serious and enduring nature, and they need help with those problems. You need to treat the cause of the depression. I hope we’ll come on to talk about that, because it’s a very interesting subject. Modern medicine’s view of depression is a bit like if you had anaemia, you went along to the doctor, and they spotted the fact you had a very low haemoglobin, and they gave you a blood transfusion. Okay? And they never asked the question, “Why is it your haemoglobin keeps dropping and you have a low haemoglobin?” If you just keep giving people a blood transfusion and not asking the question why are they getting depressed, you won’t get fundamentally to solving the problem.

There are several different theories about how to change the treatment. Lord Layard, with whom I had a debate at the LSE recently, has a fascinating idea that we should set up special treatment centres specifically devoted with the provision of cognitive behavioural therapy for just things like depression. So you wouldn’t go to your GP, you’d go to these treatment centres, and you’d have a group of people who are expert in the treatment of this problem, and they would have the time to give to you, they would monitor you closely, so they would provide follow-up; they would notice if you didn’t come back for an appointment, and they would chase up what happened, and you would get the kind of support that you need. I think it’s a fascinating idea, but it is going to be hugely expensive. I think we need to come back then to thinking a little bit more about prevention and what to do about it.

But one final point I want to make is the interesting issue of gender differences that has come up. It is interesting that two to three times as many women as men seem to suffer from clinical depression. No one really knows the reason for that. Some people think it’s due to the fact that women tend to be more honest about their depression, and men are worried because of machismo of owning up to vulnerability and therefore they are not talking about their depression. There’s another theory, which is that men suffer from a thing that you might call depression, but they manifest it in a very different way. There’s a very interesting theory that men manifest their depression in a completely different way to women, which is they don’t actually manifest low mood and tearfulness, for example, they get really, really irritable. In fact, there’s a thing called Irritable Man Syndrome. There’s even a term now developing in literature called Anger Attacks, where the man suddenly gets really, really angry, and that could be the way that men manifest their depression.

What is interesting is that two to three times as many men as women appear to suffer from alcoholism, so maybe what’s going on is that the women, very responsibly, go to their GP for psychotropic administration of their depression, and the men go down the pub, and what they’re doing is they are trying to drink their depression away, because underlying most alcoholism is a depressive illness.

Another interesting thing to think about is that most women seem to develop their depression as a result of a breakdown of a relationship, whereas men seem to develop the depression as a result of a breakdown in an ambition, like they get laid off from work, or they experience some problem in terms of their careers. We’ll come back again some evolutionary theories about what that is all about, but that’s another idea that may be men and women are suffering from something slightly different when they get the depression.

One final point I want to leave you with is the idea that maybe one of the reasons why women are more prone to depression is a very basic biological one, which is that women experience more quite clear biological life transitions. For example, puberty is more clearly a biological transition, some people say because of the onset of menstruation and so on, for women than it may be for men; women get pregnant, and that’s a more clear biological transition, and then they get the menopause. These biological transitions, in terms of the massive hormonal changes that occur, place greater stress on the female body, and men don’t experience this kind of biological turmoil. That’s one theory as to why women may be getting more depression than men. And then there’s the biological turmoil or the hormonal turmoil of every month the change in hormones that occur as a result of the period cycle as well. But no one really knows is the bottom line answer.

FC

When talking about this earlier, we said we must get on to treatment, and I think we’re getting very close to it. As far as I can see, Raj, the only treatment at the moment is to have a sex change, from what you’ve been saying, and that’s something fairly unrealistic! I’d like to ask Lewis to come in, but I think I will ask Raj first of all to come in with the treatment – you give us the convention, the correct textbook way of treating – I think that’s the way to do it, Lewis, and then you can come up with a slightly unconventional way, or would you rather do it the other way round? It’s completely unrehearsed this!

RP

Okay, well I’ll have a go. I really want to talk a little bit more first though about causes of depression, because I think treatment has to arise out of an understanding of mechanism. It’s useful now to think a little bit about, when we’re thinking about depression, think about it as an emotion, and then to think about why we have emotions, what’s their point, and this is where evolutionary theory becomes very important, because until evolutionary theory came along, our understanding of the why, the answer to the why question, why does this happen to us, was very uninformed. So let’s start off by thinking about why we have emotions.

Well, emotions are biologically programmed into us because they help, fundamentally, our survival. They allow us to survive and pass on genes to the next generation. So let’s take an example of a classic emotion, which is anxiety. We all experience anxiety and we see animals clearly experience anxiety, and anxiety is a very, very unpleasant emotion, so why do we have it? Well, we have it because it aids our survival. It’s clear that we have this very adverse experience called anxiety and fear that we do things, like we avoid the edges of cliffs, or if a tiger is bounding towards us, we experience anxiety and panic, and one of the things about panic is you get the hell out of there! That’s what panic does to you, and panic is a biological programme that gets you to feel so terrible, so quickly, that you get the hell out of there rapidly. It’s clear that experiencing panic was of evolutionary benefit to our ancestors, because those that didn’t experience panic when a tiger was bounding towards them didn’t survive to pass on their panic genes to the next generation. Now, here’s the really interesting thing about panic: panic is obviously the outcome of a system, and at the start of the system has to be an appraisal mechanism. You have to appraise your environment and determine that there’s a tiger bounding towards you and this requires panic to kick in.

You can have the sensitivity of that system set at different levels. Suppose you have the sensitivity of that system set at a level whereby you begin to panic when the tiger is about ten yards from you. That probably is not going to be a system that survives for very long. But suppose you have the system set so that when you hear the crack of a twig you begin to think, “Oh-oh, there may be a tiger nearby. I’m going to get the hell out of here!” That is a system that probably is going to get passed on. One of the interesting things about the crack of the twig system is that probably there are lots of false alarms. Many times the twig will crack and there will be no tiger, but the system is such that even if there’s only one tiger in a hundred cracking of the twigs, the fact that you survive that tiger bounding towards you is such a powerful genetic mechanism, the system is set that sensitive. In fact, if you do some calculations – if you calculate that the cost to you of running away when there is no tiger is, let’s say, 200 calories, but the cost to you of a mauling by a tiger is 20,000 calories, then actually, the system could be set that only one per cent of the time the crack of the twig means there really is a tiger, for that to work in your benefit.

The really interesting idea here is that, it’s called the smoke alarm theory. The smoke alarm theory is that you have a smoke alarm at home, and really you have a smoke alarm because you don’t want the house to burn down, right, but often the smoke alarm goes off because you are burning your toast. Now, it makes sense to have the smoke alarm go off quite a few times because you’ve burnt your toast just to catch the one instance when the house really is burning down. What this leads us is to the idea that maybe we have systems built into our body that are set at a system level of hyper-vigilance, that often they spot threat when maybe there is no real threat, because it makes biological sense to think there’s a tiger when there isn’t one, and maybe, maybe what we can do by understanding that evolutionary theory is understand why we get anxious and depressed and do something about it.

Now, going to depression, one theory about what the evolutionary purpose of depression is that if you lived and evolved into groups of people that were around 150 to 200, for thousands and thousands of years, which is actually what we did, when someone got depressed and they withdrew and they manifested all the signs of depression, then people noticed around you, because they were close to you: they noticed that you were depressed, they noticed the biological changes, and they didn’t expect you to work as hard or to compete as much as the rest of them, and they gave you social support. So the depression got noticed and it attracted social support, and then maybe because people rallied around, you felt a bit better.

In Central London, if you’re feeling a bit depressed, you step on to the tube train, notice the indifference of people around you. Maybe in the modern, busy, urban cultures in which we now live, beyond the 150 to 200 people who would normally know you very well, depression becomes maladaptive, because people don’t notice that you are depressed and they don’t rally round and provide support. We’ll come back to the social support idea a little bit further, but I think I’ve rambled on for long enough.

FC

I think straight in your court now, Lewis.

LW

Well sorry, can I just say that depression is never adaptive. You’re confusing sadness with depression. It’s very common with doctors, may I say! My friend Randy Nessie has a model that one of the functions of depression is that you’re not achieving one of your goals, you get depressed, and therefore you re-assess which way you’re going. He’s confusing – I’ve told Randy – he’s confusing feeling low, that’s sadness, with real depression. He says, “Lewis, how many people have you spoken to?” So I said, “I’ve spoken to, I don’t know, 50 or 100.” He says, “We’ve got a sample of about 1,000.” I said, “I don’t care. You’re wrong!”

It’s very interesting, if you haven’t been depressed, it’s very hard for you to understand what it is. It’s not simple sadness, it really isn’t.

I want to talk about treatment. I think the important thing about treatment is, I absolutely agree, GPs really just don’t understand much about depression, and psychiatrists do, and the two ways of treating depression are the psychological and the bio-chemical. Okay, there are anti-depressants. I’m just changing my anti-depressant. I’m taking the new one on Saturday. I’ve got to cut down on Seroksat this week. Although people attack Seroksat and all these anti-depressants, I’m afraid I’ve found them in many ways very helpful, and they do help you survive. Yes, they have nasty side effects. I’m terribly sorry, that’s the way the world is, and the trick is to find the one that suits you, and you need a clever psychiatrist to help you with that. New ones come out. They are pretty crude, the anti-depressants, but nevertheless, they save many, many people, and all the hostility towards them and the drug companies I think is totally misplaced, but I’m very happy to discuss that.

The other approach to the question is cognitive behavioural therapy. I don’t know how familiar you are with cognitive behavioural therapy, but that is really about changing your negativity. I’ve had a lot of cognitive behavioural therapy. It’s really discussing with the therapist the way you think, and that’s the thing, and for the therapist to show you that many of your negative thoughts are wrong, that you keep a diary, you discuss it with him. One of the points about keeping a diary is very important. When you’re depressed, you never believe you’re going to get better. If you’re with a cognitive therapist and you keep saying this, he or she can point out, “But look, last Thursday, you felt better.” You know, you would have denied that if you hadn’t had it in the diary. I know that this is a funny little model, but I like it. The man says, “Nobody loves me,” and therapist says, “What about your dog?” The man says, “That’s true, my dog loves me.” Now you may think that’s trivial, but when you’re clinically depressed, even the slightest crack in that negative gloomy situation – I see someone nodding – you’ve been through it, you know what I mean – is a step in the right direction. If you haven’t been depressed, it’s very hard to understand that. What I really would emphasise very strongly is partners cannot jolly you out of your depression. Carers cannot do it. They can be supportive, but you really need professional help, and the best way forward is to have cognitive therapy together with anti-depressants. As I explained, why I’m so against psychoanalysis is that the one thing you don’t need when you’re depressed is to be confronted with more negative images of how terrible your parents were and so forth and so on. It just makes things worse. So my view is – and the evidence is - that cognitive therapy can help. Even with anti-depressants, all the clinical trials show the same thing: two-thirds get better, one-third don’t (half of those are on placebos), so you have to treat about four people in order to really affect one or two.

Anyhow, this is your subject – you’re the doctor!

RP

Yes, it’s always very worrying when someone says, “This is your subject – you’re the doctor!”

LW

He doesn’t mean it!

RP

Yes, that’s right!

So just going back to what can be done about depression, which I think is a really important question, going back to an understanding of why it might exist. I want to go back to this community that we evolved to live in, which was 150 to 200 people, and if you think about that community we evolved to live in, over thousands of years, one of the things that would have happened is that we would have found the role by which that community needed us. We would have ended up doing something that was vital to the functioning of that community. In other words, we felt needed, right? In the modern urban cultures that we live in, I am sometimes not sure if I don’t turn up at work how missed I will be, and I think a lot of people feel that. We’ve lost the sense of being needed by others. There’s a lot of ideas around that maybe that is one of the things that kick-starts depression on its way.

I want to bring up another model or word that’s hardly ever used in the way we think about depression today, but friendship. I think friendship is, in my experience of preventing depression, a vital factor. Now, people say, “Yes, but in modern society, we have lots of friends.” Well, we have acquaintances, but are they genuine friends?

David Bust, an evolutionary psychologist in America, has a fascinating theory, which is that he thinks that when times are tougher, as times generally were in the past, he says there were things called critical incidents that tended to happen to you, i.e. bad stuff that happened to you, and then you discovered who your true friends really were, because that is when you discover when your true friends are – when things aren’t going so well, the people who rally round. He thinks that in the evolutionary history of this community we would have lived in, 150 to 200 people, there would have been critical incidents happening quite a lot, and we would have known who really were our friends and who weren’t. In modern society, we have lots of acquaintances, but how many of them are true friends? The research evidence for women and their depression is that for those who have one intimate confiding relationship, it’s a very strong protective factor for preventing depression. When I spoke to Professor George Brown, who pioneered this research, he used this technical term “an intimate confiding relationship,” and I said, “So what you mean is having a friend is really helpful?” He thought about it and he grudgingly accepted the word friend, but you know, professionals of course have to use jargon to protect the body of knowledge from the lay public, so basically all that science tells you that having just one genuine friend, i.e. a person that you have an intimate confiding relationship with, is a very powerful protective factor against depression.

I wonder if this is a big clue as to why modern wealthy society is more prone to depression, because we are so busy striving and being competitive, trying to achieve significance in the workplace, that actually we are missing out on the power of basic friendships, because we have so little time for each other, because friendship requires time. What’s the time of your life that you have your most friends? It’s when you are in your late teens and early twenties, because you have most time then to devote to other people.

So I want to suggest that maybe we need to think again about the importance of friendship, and maybe at schools talk about that as being maybe a vital protective factor in terms of depression.

FC

Were friends useful to you, Lewis?

LW

Oh yes, absolutely! Yes, of course, and one’s partners are enormously helpful. I’m not very happy about this…

RP

I’m picking that up!

LW

You’re confusing sadness and depression. I think the biological evolutionary value of sadness is that you try and make up the loss, and other people can help you make up the loss. It’s when it becomes excessive… Listen, depression is to sadness as cancer is to more normal cell division. Normal cell division is absolutely fine, but things go wrong, I’m terribly sorry.

Also, can I just make – we’re fighting now! – I don’t think that modern society has more depressives than non. If you go to India, where I’ve been, the incidence of depression is really quite high there. However, it is manifested in different ways. You’re not allowed to say you are sad. When Arthur Klineman went to China at the time of Mao, there were no depressives in China. They all had chronic pain, and when he examined them, he found they were severe depressives. It is very important to realise that one aspect of depression can lead to quite severe physical symptoms.

RP

Okay, just one final point, and then let’s throw it open to the floor any second now, just one other thing to think about, because we’re talking a lot about depression, and it might be useful also to think about happiness and the causes of happiness as a way of also thinking about what to do about depression. Again, evolutionary theory might be of help here, because it’s actually an evolutionary puzzle, believe it or not, as to why happiness exists, because the evolutionary biologists will tell you that it’s quite possible to create an animal that will survive quite happily as long as it’s full of these negative emotions that it avoids, like anxiety and pain, etc etc. In other words, for example, if you think about sex or eating, you create a thing called hunger that the animal experiences, which is a deprivational state, and then it works quite hard to correct hunger by eating. It experiences deprivational states when it doesn’t have sex, and then it has sex, and that in a way ensures that it passes its genes on to the next generation. You don’t need happiness from an evolutionary theory standpoint, so why does it exist?

Well, there’s a fascinating idea around in evolutionary theory which is about what happiness is; the fact that when you are happy, you are more generous, you’re more expansive, you’re more basically pleasant to be with. If you are pleasant to be with, what you are doing is you’re putting credit in the bank of human relationships, so that when you do get depressed, people will remember that you were a happy person at one point and were pleasant to be with, and you can draw on that credit. That’s a very interesting idea I think, that happiness does have an evolutionary purpose which goes back to social cohesion and social cement. It bonds people together, and it makes them hang out for you and come round and visit you when you are not so wonderful to be with.

© Professor Lewis Wolpert and Professor Raj Persaud, Gresham College, 23 November 2005

This event was on Wed, 23 Nov 2005

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login