Discovering Australia: The legend and the reality of the navigator-explorer Matthew Flinders

Share

- Details

- Transcript

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

Matthew Flinders is remembered as one of Britain’s greatest navigator-explorers. But to what extent does the legend fit the reality?

In 1791 Mathew Flinders first sailed to the south-seas as a seventeen year old midshipman on a two year voyage with Captain William Bligh. Three years later he returned to Australia and in a tiny dingy named Tom Thumb explored much of Australia’s south east coast with his good friend lieutenant George Bass. Later, Flinders and Bass sailed in the Norfolk and discovered that Tasmania was a separate island from the mainland of Australia.

After returning to England Flinders was again sent in 1801 to complete the exploration of the entire Australian coast line in the Investigator. In April 1802 while charting the south coast where no ship had sailed before, he had a remarkable chance encounter with another explorer. Frenchman Nicholas Baudin had been sent by his government on exactly the same quest: to explore the remaining uncharted coast of the great southern land and find out if the west and east coasts, four thousand kilometres apart, were part of the same land.

And so began the race to complete the first complete map of Australia and to finish the exploration of the region started two hundred years before by the Dutch, the Portuguese, the Spanish and later the French and the English.

Flinders three year voyage featured great hardship, sickness, the death of crew, shipwreck and finally imprisonment. Flinders beat his French rivals in discovering and charting the remaining unknown coast but they beat him to publishing the first complete map of Australia.

Download Transcript

17 July 2014

Discovering Australia:

The Legend and the reality of the

navigator-explorer Matthew Flinders

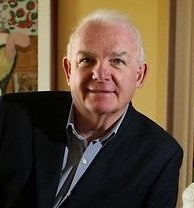

David Hill

Matt Johnson

Good evening, ladies and gentlemen and distinguished guests. It is a great pleasure to welcome you to Australia House for this evening’s joint Flinders University and Gresham College lecture. For those of you I do not know, my name is Matt Johnson and I am the Deputy Agent General for the State of South Australia, based here in London.

Now, I think you had all be aware that this week is the bicentenary of the passing of Captain Matthew Flinders, and the big red thing here in front of me is a memorial statue that we will be unveiling here tomorrow morning to commemorate his life and his work. On the eve of the unveiling, Gresham College and Flinders University thought it would be wonderful to provide a lecture on Matthew Flinders, and, in some ways, set a bit of a scene for tomorrow and the upcoming commemorations over the weekend.

We are absolutely delighted to have David Hill with us this evening, all the way from Australia, and we will hear more about David in just a moment.

I can well imagine that your curiosity is somewhat piqued about this thing, and the temptation to lift that silk is strong, is it not? It is like the reaction when you see a sign that says “Wet paint – do not touch”… You have just got to touch it, do you not? But we are not going to.

What I can do though is show you a miniature of that statue, and it is here, and I am going to unveil it now for you.

[Audience applause]

So, in addition to the main memorial statue, our artist, a British artist, a renowned artist, Mark Richards, has produced a limited edition of these maquettes. They are individually numbered and authenticated. We have actually been selling them to fund the cost of the actual statue, so there is no Government money that has gone into this statue. It has been a private endeavour, supported by the State of South Australia and a number of private individuals who came together to form a steering committee called the Matthew Flinders Memorial Statue Steering Committee. Now, the good news is that a few of these are still available for sale. We have sold 56 of the limited edition of 75, so that means that there are 19 left. If you are interested in buying one, please speak to me later on this evening. All proceeds go towards the statue and also a scholarship fund that we are launching in 2016 to provide a way for British students to study at Flinders University, Matthew Flinders’ namesake university, in Australia.

I would now like to introduce to you Alderman Professor Michael Mainelli, Emeritus Mercers School Memorial Professor of Commerce at Gresham College. As he comes forward, I also want to let you know that, for those of you who are not going to be here tomorrow morning for the unveiling – it is a ticketed event, invitation only, unfortunately – you will be able to see this statue at Euston Station from Saturday morning. When the trains start running, that thing will be there on Euston Station.

Professor Mainelli…

[Audience applause]

Michael Mainelli

Good evening, ladies and gentlemen, and behalf of the trustees, the Provost and the team at Gresham College, it is my real delight to welcome you tonight to this special lecture, in this special hall, about this special person, with this special lecturer, David Hill. I feel a bit like Mr Bean up here – I kind want to reach over, get entangled in it and pull it off, but we will see how it all goes tomorrow morning.

Now, this is a wonderful event, with so many contributors who have made it all happen, and very much I think in the cooperative spirit of Matthew Flinders himself, unlike some of the nasty competition he may have experienced from the French. I am not going to try and read out everybody’s biographies or embarrass David – it has all been written down. But what I thought I would just like to spend a couple of minutes on is “Why does Gresham care at all about navigation and how did we wind up here today?” because it is a fun story.

Gresham College, for those of you who do not know, is named after the merchant, adventurer, banker, Sir Thomas Gresham, born in 1519 and died in 1579. It is my belief that he founded Gresham College partly in order to share Oxford and Cambridge learning on navigation with ordinary merchant seamen. He required lectures to the public, not just in Latin but also in English.

Strangely, during his time, and my history is not incorrect, Sir Thomas might have had a personal interest in Australian mapping. He would have handled some of the Dieppe maps. These were a series of large handmade maps produced in France in the 1540s, 1550s and 1560s, and they were commissioned for wealthy and royal patrons, including somebody that Sir Thomas worked for, Henry VIII. Controversially, these Dieppe maps depict the southern continent, Terra Australis, incorporating a huge promontory called Java la Grande. Now, historians and cartographers argue whether this early mention of Australia was based on actual navigation, just talked about, or only guessed, and to someone who produced some of the first digital maps of the world back in the Eighties, what I love about these Dieppe maps is that they mark out lands “yet to be discovered”. I wish we had had that computer function back in 1980. You cannot have any more powerful map-making than that: finding things before they are discovered.

And it is that leap into the unknown that characterises our College. For those of you new to Gresham, you may not be aware that, since 1597, we have been giving free lectures to the public on a range of subjects, including astronomy, geometry and navigation. The first Gresham Professor of Geometry, Henry Briggs, popularised common base-10 logarithms. The Royal Society was founded at Gresham College in 1660 and resided there for half a century, very much focused on navigation, conducting numerous lectures and publishing copiously, and Gresham College was at the heart of the controversy over John Harrison, his chronometer and the prize for the longitude problem. As the anonymous 1663 Ballad of Gresham College observed: “The College will the whole world measure, which most impossible conclude, and navigation make a pleasure by finding out the longitude. Every tar shall then with ease sail any ship to the Antipodes.”

Rather oddly, this lecture began on an English train, not an Australian boat. Sir David Higgins and I were travelling together on Network Rail back in September 2012, when we found a joint interest in navigation. He challenged me on Matthew Flinders, to which I could produce a reply, feeble, but a reply nonetheless. He then regaled me with a host of information about flinders himself and his burial at St James, Hampstead Road, and the odd platform connection for David, then Chief Executive of Network Rail, was not just Harry Potter and Platform 9¾ at Kings Cross but also that Flinders’ gravesite is thought to lie under what is now Platform 15 at Euston Station. It was then that I found out about the plans for the memorial statue, and we both agreed, along with Professor Tim Connell, that a commemorative lecture was required, and with the enormous help and kind generosity of Matt Johnson, the Australian High Commissioner, the South Australian Agent General, the Matthew Flinders Memorial Committee and Flinders University, we have been able to entice the eminent businessman and scholar David Hill, also of the railway trade, to fly to London and present his view of the navigator-explorer Matthew Flinders, which he uncovered writing his highly acclaimed book, “The Great Race”, the race between the English and the French to complete the map of Australia. I am sure, like you, we all look forward to David’s lecture, knowing already we are going to learn many things in the next hour, long before we have discovered them. David…

David Hill

Well, I cannot tell you how special this is for me to have been invited to deliver this lecture, and particularly here, in Exhibition Hall of Australia House, because I first came here a little over 50 years ago, with my two brothers, to be processed for migration to Australia. It was by far the biggest building we had ever seen, and one of the grandest, and it remains one of the grandest, and to be here tonight with so many old friends, not only from Britain but from Australia, and my big brother, Tony, who never came to Australia with us because he was in the RAF when we left, and has remained totally a Pom, and his wife Jillian, and my wife, Stergitsa, and Damian are here as well.

This coming Saturday, it will be the 200th anniversary of the death of the explorer Matthew Flinders. He was only 40 years old. He had been increasingly unwell since returning from his momentous expedition to Australia, and as he lay dying, he would have at least had the satisfaction of holding the 800-odd page of a magnificent journal he wrote, not only of his travels but of the history of the European discovery of Australia. He would have also had the satisfaction before he died of seeing and holding this wonderful Arrowsmith engraved map, the complete map of Australia, because Flinders completed the exploration of the unknown coastline of Australia, and what is significant about this map, apart from it being the complete map of Australia in 1814, he has observed New Holland, he has observed New South Wales, and Terra Australis, but he added his own Australia, for the first time. He said it was more pleasing to the ear, and this was without the approval of his superiors, and he said it also is consistent with the other great continents of Asia, of Africa, and of America.

Flinders did not discover Australia. Indeed, we should say, this whole story is only about the European discovery of Australia because, of course, it had been discovered some 50,000 years before by the Australian indigenous peoples.

Flinders completed an exercise that had begun 200 years before, and the first known recording of the charting of the Australian coast were by the Dutch East India Company in 1606. a little piece of the western side of the Gulf of Carpentaria in Northern Australia, and over the next 30 years, in search of wealth and trade and gold and silver, the Dutch East India Company sent a series of expeditions to the north, to the west, and to the south-west of Australia, and it is remarkable, in the middle of the 1600s, more than 100 years before Cook, the Dutch were able to produce maps like this, which pretty well accounted for about 60% of the Australian coast. It made the British relative latecomers to the exploration of Australia. Of the contributors to this map, the one that I find most appealing was from the south-west tip across to current-day Ceduna, Peter Nuyts, in 1627, got as far as the islands he named St Francis and St Peter, which remain the oldest named places in South Australia, and was the inspiration, 100 years later, for Jonathan Swift’s “Gulliver’s Travels”.

Of course, the completion of the East Coast of Australia was by Cook. The Dutch, incidentally, finding nothing worth exploiting - no wealth, no gold, no silver, nothing to trade - by the middle of the 1600s, left Australia, with no further interest. I should mention, because Michael mentioned the Dieppe maps, there is a lot of compelling evidence that, even before the Dutch, the Portuguese, possibly the Venetians, and the Chinese had all charted parts of the Australian coast, and while it is very compelling evidence, it is not conclusive proof.

Cook was not sent primarily to discover Australia, the East Coast of Australia. He was sent to Tahiti in 1768 to observe the transit of Venus, which was an important astrological phenomenon that allowed the measurement of distances between the planets and the stars, which was very helpful for navigation, and it was only after he had done this that he was given a secondary instruction to sail east to the great unknown south land, and he did this with enormous success. He first of all circumnavigated the two islands of New Zealand. New Zealand had been found by the great Abel Tasman in 1642, and hardly anybody had been anywhere near it until Cook got there. And then Cook sailed west to what is now the Victorian, lower Victorian area of Point Hicks, and then began, in 1770, this phenomenal 4,000km voyage of navigation up the East Coast of Australia. He went through the Torres Strait and to a place called Possession Island, and he planted the Union Jack, and he declared, on Possession Island, all of these territories in the name of King George III, as a British possession, in much the same way as the Dutch had put down their flags on the West Coast of Australia and Abel Tasman had done it in Van Diemen’s Land and claimed it for the Dutch. But the truth is, Cook found nothing of great interest to compel the British to stay there, and after Cook left in 1770, the British ignored Australia, as the Dutch had done before them.

But eighteen years later, the British are desperate to do something about the problem of a large number of surplus convicts, and embarking on yet another great chapter, 1788, they sent Arthur Phillip, with about a thousand people, on eleven tiny ships, to start the convict settlement in Botany Bay, which proved incidentally to be a disaster and was abandoned within days, and they instead went and settled the first settlement in Sydney.

The first dozen years of the convict settlement in Sydney was a disaster. They nearly starved to death. It was a struggle. They could only just survive with the arrival of the second and subsequent fleets with extra food. There was very little opportunity to explore any more of Australia. There was a shortage of shipping in the new convict settlement. The British were preoccupied with yet more wars with France, and the only serious navigation done to explore the surroundings of Sydney was by a young 24 year old, Matthew Flinders.

Believe it or not, he did the first exploration south of Sydney in a boat called the Tom Thumb, which was only nine-foot long, with his good friend, the ship’s surgeon, George Bass, and George Bass’ servant, and they explored hundreds of kilometres of the coast below Sydney.

In a slightly larger boat, Flinders became famous because, with George Bass again, they circumnavigated Tasmania, or Van Diemen’s Land as it was known then, and proved it to be separate from the Australian mainland.

Flinders went back to England in 1800. This is the scene, this is what we knew – oh, I was going to mention, at the same time, it was not only the British who were interested in the further exploration of Australia. The French, somehow, in the most turbulent period of their history, in the late-1700s and the early-1800s, committed a number of remarkable voyages of scientific discovery – Bougainville, St Alouarn, Dufresne, La Pérouse, d’Entrecasteaux, and these – the biggest one of course is La Pérouse, who went on this massive five-year voyage around the Pacific and ended up in Botany Bay three days after the arrival of the first fleet, and three weeks later, went and disappeared. The French were far more interested. The French public were far more interested in these great voyages of exploration and discovery than the British, and when La Pérouse disappeared, this is a painting, a very famous painting, of La Pérouse being given his instructions ceremonially by Louis XVI, but such was the interest and the concern when La Pérouse disappeared that Louis XVI is reported to have said, on the eve of his execution, “Is there any news of Monsieur La Pérouse?”

Of all of these French explorers, apart from Bougainville, all of the others died during their explorations – all of them. It underlines just how hazardous these voyages of exploration into the Pacific and to Australia were. First of all, the ships they sailed on – we measured this hall today – the ships were about the length of this hall, and they all leaked. They all had to be constantly pumped or you would sink. You would be on these voyages for a minimum of two years. They were extremely hazardous, with extremely high rates of fatality. There was no fresh food of course after you left port, and the standard food was salted meat and hard-tack biscuit which had been baked as dry as possible. If you had any teeth, it was very hard to break. They were infested with weevils, which ironically was a source of protein that a lot of the sailors would not have.

The biggest cause of death on ships, right up until the middle of the 1700s was scurvy, which came about with the deficiency of Vitamin C. When they called in at the Dutch East Indies ports, the fatality rates, instead of coming down, went up because of the polluted water and the outbreaks of dysentery that wiped out entire crews. On Cook’s voyage back to England after discovering the East Coast of Australia, he lost a third of his crew from dysentery after calling in at Batavia, half of the crew of the Endeavour.

After the French explorations and Cook, this is 1800… This map was published in 1799 and, as a result of Cook discovering the two islands of New Zealand and the East Coast of Australia, the biggest missing bit is the large unknown coast of South Australia, and it was called “the unknown coast”. The only knowledge of the hinterland of Australia was 30 or 40 miles west of Sydney, the only European settlement, and it was not even known – and bear in mind, this is a dozen years after the first fleet settled here – it was not even known if New Holland in the west and New South Wales in the east were part of the same continent or whether they were separated by a strait.

It was not the British who initiated the move to go and find out. It was the French again. Two years before the British, on the left, Nicolas Baudin was appointed by Napoleon, with instructions to explore the unknown coast of Southern Australia to determine whether or not it was one continent and to complete the map of Australia.

Of course, this prompted the British – Matthew Flinders had only just got back to England from five years in New South Wales when the British were prompted by the French. Most of the settlement in Australia by the British – Victoria, Tasmania, West Australia, Northern Australia – was prompted by a fear of the French. What is remarkable about this commitment of the French, through this turbulent period of their history, to voyages of scientific discovery, none of it involved instructions to settle or colonise, which contrasted them with the British. The French made a bigger commitment to this venture, to this quest to complete the map of Australia. Baudin was given two ships, Flinders only one. Baudin had a total crew of over 250 on his two ships, Le Geographe and Le Naturaliste. He had 24 scientists. By contrast, Matthew Flinders had a total crew on the Investigator of 78 and only six scientists. Both explorers carried all of the old charts. Neither of them completed the map of Australia by themselves. They filled in the gaps. Baudin had 58 old charts going back to the Dutch and some of the Dieppe maps as well before that, not that they were of any great help, and both explorers, even though France and Britain were at war, were given passports from the other side that, provided they strictly keep to scientific and knowledge and not military, they would be exempted from any hostility from the other side. This became a problem for Flinders later because he operated in breach of his passport.

Baudin left first. Baudin left Le Havre in October 1800 with – oh, both of them had instructions to make great haste because they both knew the other was on the same quest, so here began the race. But Baudin was a bit eccentric. He was late rounding the Cape of Good Hope, and even before he reached the French-controlled island of Mauritius, he was complaining that the scientists, the large number of scientists he had aboard, were ill-disciplined for life at sea, but he had a problem even with his own officers.

When they got to Mauritius, a number of the scientists abandoned the expedition altogether because they were having too good a time, and a number of Flinders’ officers – I think this would have been unheard of, at the time, in the British Navy, instead of helping prepare the ships for the next leg of the voyage, reported sick and went into the hospital in St Louis, and Baudin recorded he was concerned about them, his officers who were too sick to work: “At 11 o’clock, I went ashore and visited the hospital to see the officers who were to be found there. The Sisters of Charity assured me that the gentlemen sometimes returned in the evening, but very late. I did not find a single soul.”

When he finally left Mauritius and sailed to Cape Leeuwin, which is the south-west tip of Western Australia, with instructions to immediately explore the unknown coast – and bear in mind, he is way ahead of Flinders, even though he is running late, and then a bizarre decision that even bewildered his colleagues, he said that it is now late-May, too close to the Southern Hemisphere winter, so he decides to abandon the search of the unknown south coast and heads up the West Australian coast, charting the bits the Dutch had missed, all the way to Timor, to Kupang in Timor, where he gets fresh water and provisions, and sails back down the coast. But of course, by this stage, before he gets to the bottom, he does not know, but Flinders has already passed him. Baudin then goes across the great Southern Ocean to Van Diemen’s Land and, inexplicably, spends another six weeks collecting botanical and other samples in Van Diemen’s Land, before sailing up the east coast of Van Diemen’s Land and through Bass Strait – this had been found two years before by Flinders. So, he starts, the following year, from the east, searching the unknown coast, and in March 1802, he bumps into Flinders coming the other way, and Flinders has already searched and discovered the unknown coast.

Flinders had left England nine months after Baudin. Oh, incidentally, this is an irresistible image that is well-recorded of the encounter between Le Geographe and the Investigator, and Matthew Flinders being rowed over, in deference to the more senior rank of Nicolas Baudin.

Flinders left nine months later than Baudin because the British expedition, I think, was hastily put together to try and catch the French. Incidentally, Flinders very nearly did not go. He was almost sacked before the Investigator left. While Flinders had been in Australia for those five years, he had corresponded with a family friend, Ann Coombe, and he was only back in England for a year where he married her and, at the same time, he put himself forward as conducting this new exploration of Australia and promised – this is audacious, unheard of in the Royal Navy – he promised to take her with him. After they left the Thames and were going down to Portsmouth, he got caught, and the inspectors of the Admiralty, who were aboard inspecting the vessel, actually reported that they were shocked to encounter, “…in the captain’s cabin, Mrs Flinders without her bonnet!” It was the intervention of the very influential botanist Joseph Banks, who of course had been on the Cook “Endeavour” voyage, that had saved Flinders, but I think there was more to it than that. The British were spooked by the fact that Baudin was nine months ahead and so poor Ann was just dumped at Portsmouth. Flinders was a very dedicated sailor, but when he had to make a choice between his new bride and the expedition, he did not hesitate, and poor Ann was left.

Flinders only took three and a half months’ sailing to get to Cape Leeuwin, overtook Baudin, and along the South Australian coast, he went beyond where the Dutchman Peter Nuyts had gone, and he not only charted – and Flinders’ genius was the meticulous and unbelievably accurate charting that he was able to do, probably unequalled or very close to it at the time. He found that Australia was not separated, New Holland and New South Wales, by a sea or a strait, but there were two giant gulfs and you can see Kangaroo Island. Just before he reached the first of these two gulfs, one of his cutters went aboard for water, and eight of his 78 crew were drowned, including the First Mate, Thistle.

There is a very interesting story about Thistle. Flinders journalised that Thistle was very superstitious and knew he was going to die. He had been to a fortune teller before they left Portsmouth, who predicted it, so closely, and there were other aspects to the prophesy that later came true as well.

Flinders charted the two gulfs. They were both named after Lords of the Admiralty, the small one, St Vincent, where Adelaide is now, and the larger one, the Spencer Gulf. They were both Lords of the Admiralty. Spencer was the great-grandfather of Princess Di, and of course the great-great grandfather of Prince William, who is unveiling Flinders’ statue tomorrow, so he has a very personal involvement in it.

After leaving here, Flinders continues, and that is where he meets Baudin coming the other way, and again, bizarre behaviour by Baudin. Flinders, in deference to the senior rank, rows over to Le Geographe. With him, because Flinders does not speak French, he takes his botanist, Robert Brown, who did speak good French. They are greeted by Baudin, in full dress uniform, who does not speak any English, and takes them to his cabin, but does not invite any of his officer colleagues to join them. They met that afternoon and it was civil enough and they explained where they had both been, and they agreed to meet for breakfast the next morning, which again happened. Both wrote accounts of this. Baudin had used Flinders’ maps when he had gone round Tasmania and through the Bass Strait, but was critical of the maps, and Flinders formed the view that, even on the second meeting, Baudin had no bloody idea who he was!

Anyway, after this encounter – and what were the odds, where nobody had every sailed before, off what is called Encounter Bay off South Australia now, these two…the first explorers bump into each other…

After their meeting, Baudin, notwithstanding the fact that Flinders had already charted it, heads west, and he does his own surveys of the two gulfs, and what really upset the English later is that, even though Baudin had got there first, the French named them Gulf Napoleon and Gulf Josephine, ignoring the fact that Flinders had been there.

It is now the onset of winter. Flinders continues his survey to the east, along the coast, and it is the onset of winter and so the French and the English, they have got passports, the French, and they go to Sydney and they are hosted by this guy, the hard-drinking but very competent Governor of New South Wales, Philip King. King was a great supporter of Flinders, but he became a great friend of Baudin. King spoke French. He was the last person to have seen La Pérouse alive before La Pérouse…because he was on the first fleet with Arthur Phillip and was sent by Arthur Phillip to meet La Pérouse in Botany Bay.

The English and the French got along reasonably together, but, by this stage, Baudin is totally detested by all of his crew. Matthew Flinders describes a scene at dinner at Government House in Sydney, when Henri de Freycinet, a rather precocious 24-year-old lieutenant on Le Geographe, sidled up to Flinders to complain about Baudin, and he, according to Flinders’ journal, he said: “Captain, if we had not been kept so long picking up shells and catching butterflies in Van Diemen’s Land, you would not have discovered the South Coast before us.”

Later that year, after they had re-stocked and re-equipped, the French left Sydney and went back down to the south and then up the West Coast of Australia, and they had collected 200,000 specimens of botany, of minerals, and something like 70-odd live animals to take back to France. So, on the one hand, they want to complete the mapping of Australia, and on the other hand, they have got to keep these animals alive. The French, incidentally, fed the kangaroos – they had kangaroos, wombats and emus, and in fact, a lot of them got back alive and ended up in the Malmaison Gardens of Empress Josephine in Paris.

On the way back, they went via Mauritius, French-controlled Mauritius, and Baudin died of TB, yet another in this long list of French explorers who died, and nobody had anything nice to say of Baudin.

The task of writing up the expedition passed on to Francois Peron, who was one of the scientists in the French expedition, and in 800-pages of the account of the Baudin expedition, he never mentioned him by name once, except when he died. He just said, “Citizen Baudin ceased to exist.”

Flinders left Sydney and went north, on the so-called circumnavigation of Australia. Now, this shows how he had gone across the southern part and into Sydney, and then, in 1802/3, goes up the coast to do some charting on the north coast that Cook had missed, and then he went into the Gulf of Carpentaria. The Flinders’ charting of the Gulf of Carpentaria was so precise they were used on the Royal Australian Navy maps until relatively recent years.

It is about a 14,000km circumnavigation, but when he got to East Arnhem Land, he stopped. He reported that the Investigator was rotting so badly that some of the boards underwater were powderising, and he abandoned the survey. Now, this remains a puzzle for a number of reasons. He is 6,000km from Sydney and he is 2,000km from Kupang in Timor, so he heads for Timor, picks up water and provisions, his crew get sick and they start dying, they sail down the West Australian coast and back to Sydney, and they abandon the rotting Investigator in Sydney. But after Flinders went on another ship back to England, King, Governor King, repaired the Investigator, it continued to sail for another 70-odd years, and actually turned up back in Australia in 1854 during the Gold Rushes, bringing supplies to the Gold Rush.

Now, what is equally puzzling about Flinders abandoning… Every Australian child at school is taught that Matthew Flinders was the first person to circumnavigate Australia. Well, that is stretching the definition a bit. The fact is, Flinders, by going to Timor and on this route, you can see, did not even see, let alone navigate, about 40% of the Australian coast.

What is even more puzzling is he was fastidious about his instructions, and one of them was he was supposed to find deep-water ports on the North-West coast of Australia for British trading ships, who were being fleeced by the Dutch if they went to Batavia or to Kupang.

So, Flinders ends up with a number of his crew dead. Some of them were dying as the ship, with dysentery, as they approached Sydney Heads, and one of them, the gardener, Peter Good, died after they got back to Sydney. But with the help of his good friend, Governor King, Flinders – bear in mind, they know the French have gone, they know the French have got enough information to complete the first map of Australia, they are in a hurry, and King gives Flinders a new boat, a new ship, called the Porpoise, and away he goes. They are in a hurry. He has got to get back and put his maps together. Bear in mind, with this charting, you have got thousands of bits of paper and you have got to reconcile all of the readings and put it into the map of Australia – it takes a very long time. But the sooner he gets back, the better.

So, on the Porpoise, Flinders leaves Sydney, accompanied by two merchant ships, the Cato and the Bridgewater, and 2,000km north of Sydney – you could not believe that anything else could happen in this adventure – the Porpoise and the Cato are shipwrecked on the Great Barrier Reef, and the Bridgewater sails on and leaves them to it.

These are not very clear images, but the artist, William Westall, on the Investigator, painted a series of very dramatic watercolours depicting a number of the sailors were drowned from the Cato and the Porpoise getting onto a sandbar, but once they got there, they used the salvaged sail to pitch tents and they put up a distress flag, and then Flinders and the Captain of the Cato, with a surviving cutter, small cutter, and two groups of oarsmen, and a single mast, row and sail, nonstop, back to Sydney for help.

And, as soon as they get there, Governor King, again, rallies whatever shipping they can to go and rescue the 100 men who were still on this sandbar, and when they got back there, all of them survived, the reason being that there is very high rainfall up there and there is plenty of fish.

So, the men were given the choice, the survivors, to go with these merchant ships onto China and then hopefully pick up an English ship back to England or to return to Sydney, but given the urgency of this map, Governor King had sent a small boat called the Cumberland, a very small, only 20-metres long, to pick up Flinders and about a dozen other people, and to race back to England, so Flinders can still get back without losing too much time.

But on the way - again, it is a puzzle as to why Flinders did this – Governor King had told him, “Do not stop at Mauritius,” the French-controlled island of Mauritius. Flinders said he had to because the Cumberland needed repairs, he was short of water, fresh water, and he was short of food. So, he calls in at Mauritius, but his passport was issued for the Investigator. He could not, to the French, demonstrate any orders or instructions that justified him being in Mauritius, and he was carrying military despatches from Governor King to the War Office back in London.

So, I know it is a very fashionable English thing to say that the French were vindictive and spiteful and they were trying to slow Flinders down from producing the first map, but the fact is he had plenty of evidence against him by the French, and this man in particular, Decaen, a close supporter of Napoleon’s, and he jailed Flinders and Flinders was stuck on Mauritius for six and a half years.

The first years were pretty uncomfortable. The other members of the Cumberland were progressively released, and poor old Flinders, at the end, he only had the company of his companion cat, well-known cat, Trim. I am pleased to see that the statue has very accurately got Trim on it. But, sadly, he lost Trim as well - according to Flinders, Trim ended up in a Mauritian stew-pot.

As his incarceration continued, Flinders was allowed to go and live on a country estate. It was really like the old regime, the ancient regime, and he learnt to play chess, learnt to speak French, worked on his journals, worked on his maps, went to concerts, joined card parties and so on, and had this very famous portrait painted, which eventually ended up in the hands of the crook Australian businessman Alan Bond. When Bond went broke, the receivers of the company found this under the floor of a Bond corporate jet that had reached London. The good news is it is now safely in the South Australian Gallery. I think Bond paid over a million dollars for it, which made it more valuable than anybody thought it was at the time.

Flinders was finally released in 1810. He was imprisoned in 1804 and he was released in 1810, but the French had not produced their map yet. Baudin had died. The job of their journal and their map went to Francois Peron. He died of TB. They all died early. These explorers all died early, if they did not die on their expeditions. Peron died, at a very young age, and the job was then handed over the Claude Henri Freycinet, who was in a hurry to complete the map.

Flinders got back in 1810. He was finally released because Mauritius was under blockade by the British, and they took it in 1811, and I think Decaen was trying to build some goodwill and so they took Flinders out of Port Louis, handed him over to the French Navy, under a truce, and they finally got him back to England, and Flinders spent the next four years, a massive job of reconciling all of his own measurements, and he complained too that he had to reconcile them with some information at Greenwich because the readings were different, and it was just a few days before his death that Flinders produced this complete map of Australia.

He may have been the first to discover the unknown coast, but he was beaten in the production of the first map. Freycinet, in Paris, after the news of Flinders’ release, wrote to the Government and said, “With Flinders’ release, the British are going to take the glory that should be ours,” and the Government pulled out all stops and, two and a half years before Flinders, Freycinet and the French produced the first complete map of Australia.

What really upset the English is all of Flinders’ discoveries had French names, but the good news is, in the modern maps, progressively, where Flinders and the English were there first, they now have English names, and Geographe Bay, Napoleon Archipelago, all of these places that Baudin had found first, kept the French names.

Flinders deserves the reputation for this phenomenal genius of large-scale mapping of phenomenal accuracy, and we are also very grateful that he christened our country with the name Australia.

But if you feel sorry for Flinders, and of course, fate was against him in so many instances, spare a thought for his wife, Ann. He goes to Australia with George Bass in 1795, he is away for five years, and he is writing these love letters. He comes back to England, he is there less than a year, he marries her, promises to take her, dumps her in Portsmouth when he is caught, and he is away another 10 years. He comes back, and then he dies. And, however hard it was on these explorers, you have always got to remember it was very hard on their families as well.

Thank you very much.

© David Hill, 2014

This event was on Thu, 17 Jul 2014

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login