Feliks Topolski: Eye witness to the 20th Century

Share

- Details

- Transcript

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

Between 1975 and 1989, the Polish-born expressionist artist, Feliks Topolski, worked on a 600ft mural in the railway arches in Waterloo. This masterpiece came to depict the 20th Century as he saw it, featuring the important events and people that forged the modern world that we now live in.

Topolski was born in Poland in 1907 and came to London from France in 1935. He soon established himself in the intellectual life of London and eagerly took up a position as an official war artist during WWII. In 1947 he gained his British Citizenship and he went on to make portraits of the likes of H.G. Wells, Graham Greene, Evelyn Waugh, and Harold Macmillan. His 600ft mural in the railway arches of Waterloo is now open to the public as the Topolski Century gallery.

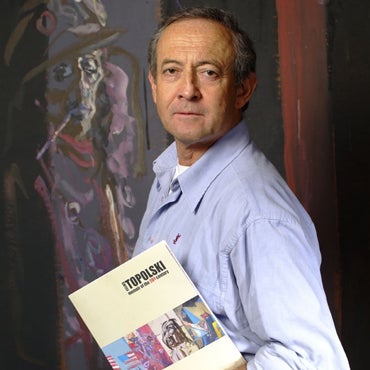

Daniel Topolski is a writer and broadcaster, and Trustee of the Topolski Century.

This is a part of the London Through the Eyes of Foreign Artists Mondays at One lecture series.

Foreign Artists in Sixteenth Century London

Canaletto: Grand Designs

Monet: The River of Dreams

Download Transcript

Feliks Topolski: Eye Witness to the 20th Century

Delivered by Daniel Topolski

22/3/2010

My father Feliks Topolski fell in love with London when he first came to Britain in 1935 to fulfil a commission for Polish newspapers to cover the Silver Jubilee celebrations of King George V. It was, he said, London's 'exotic otherness' - the revered yet absurd world of British social custom and distinctions - that fired his imagination: judges in wigs, City gents in bowler hats, grand state ceremonial parades with the military in exuberant costumes, Henley Royal Regatta and Ascot - this was meat and drink for an artist in thrall to humanity and all its endless foibles. Compared to what he described as drab central Europe, London was bliss.

His urge, his mission in life, was to 'bear witness', to chronicle the major political and social events and the iconic historical personalities that defined and fashioned the 20th Century. His reach was global but his base, heart and centre was London. It was from here that he sallied forth to draw our worlds- unfolding history as it happened - on the spot. An eye-witness to our lives, spanning 9 decades.

His love of London though meant that he focussed a huge amount of his attention on the city and its inhabitants and the extraordinary social changes that were taking place after the war: art, royal weddings and coronations, hippies, punks, theatre, famous personalities.

Topolski was, according to playwright George Bernard Shaw, 'an astonishing draughtsman - perhaps the greatest of the impressionists in black and white'. He collaborated with Shaw on many of his productions, as set and costume designer and illustrator of his books, including the Penguin edition of Pygmalion. Topolski's true and honest depictions were stunningly accurate, infused with movement, humour and compassion and performed with deceptive ease.

As an outsider, an immigrant, the eye he cast over his new fellow citizens, was always unexpected. He had an aversion to cliché and received ideas, which meant that his view - his approach and style- was unique and compelling. I would say that the central European observer has always brought a new and intellectually thought - provoking dimension to the way we see ourselves - Hungarian film makers in America, Polish writers in Africa, Jews everywhere.

My father's, often satirical, depiction of the Great and the Good in law, theatre, literature, sport, fashion, politics as well as life on the street - were well documented in his many books of images, in journals and of course in exhibitions. They were very prominent too in television programmes like the BBC's 1961 seminal series Face to Face - 50 minute long, in-depth interviews by John Freeman, each introduced by 5 or 6 penetrating Topolski portraits, of some 36 iconic figures of the time: people like writer Evelyn Waugh, Lord Shawcross the prosecutor at the Nuremburg trials and civil rights leader Martin Luther King ; the whole series has just been released as a DVD box set.

Also during this early 60's period he produced his series of 20 portraits of great British Writers for the Harry Ransome centre at the University of Texas in Austin. I'll say more on that commission a bit later.

Many of Topolski's works are held in the collections of big public institutions like The National Portrait Gallery, the V & A, the Tate, the British Museum and the Imperial War Museum - and in private collections such as the one belonging to the Duke of Edinburgh and the Queen's which hangs on the walls of their apartments at Windsor Castle and in the corridors of Buckingham Palace.

But he had to tussle constantly with a suspicious arts world 'both the avant-garde and the traditionalists - which had difficulty defining him. He was unfashionable. He didn't fit into the easy pigeonholes, mainly because he covered so many different 'isms'. Yet his work was utterly recognisable - never bowing to abstract expressionism, photo-realism or conceptual art.

When the Trustees of the Tate were discussing whether to include some of his pictures in their collection, one said: 'Too many lines. It's caricature' another said: 'we have to draw the line somewhere.' Suddenly, a hitherto silent Augustus John, intervened: 'Yes, but can you draw the line as well as Topolski?' That decided it: they took the pictures.

I suspect that my father was a little hurt that, while he was honoured all over the world, official recognition was long withheld in his chosen homeland. He affected not to care but when he was made a Royal Academician two years before he died he was secretly very pleased.

A serial unconventionalist, his style and vision was informed by his desire to document the century - to be at the centre of the action. He was fixed on contemporary themes and he did not work with other painters praise in mind; he not self-indulgent. He always wanted direct contact with ordinary people and was concerned with making a statement about a person, an event or an attitude.

In a call to his fellow artists to engage with the world, he told them 'the airless studios grow stifling. Kick the door open-the hum of life turns into a roar. All humanity is out there.' He was quoted in the Listener in 1946 saying - We need an art of synthesis, painting fed on reality, the reality of today, aware of multitudes on the move, of global oneness, torn by conflicts, and achieved, not by retrogression into 'realism', but through the formal freedom won by modern art.'

His early years were influenced by radical, atheist parents, Jewish born but deciding soon after his birth in 1907, to change their name and religion in a central Europe awash with pogroms and anti Semitism. At the age of seven, sitting outside his Warsaw home, he was drawing Cossacks riding through the streets and making illustrations of the stories in his favourite Polish books.

His mother Stanislawa recognising his talent, encouraged him and worked hard to support him. He enrolled at the Warsaw Academy of Art and came under the influence of the Director, Janus Pruszkowksi where he developed his great ability as a draughtsman. He was increasingly commissioned by Polish newspapers to produce caricatures and cartoons during the 20's - socially a golden liberal age in Poland.

His father Edward was an actor, taking his theatre troupe on tour to entertain the soldiers on the front lines, enjoying in particular the role of Napoleon Bonaparte in George Bernard Shaw's Man of Destiny. Shaw was a popular figure in Poland and when my father first arrived in London he quickly established contact with him. They enjoyed a fruitful collaboration and friendship until the playwright's death.

His parents had separated when he was quite young and he saw little of his father for a long period, spotting him occasionally, strutting in fine and dandyish clothes, around Warsaw's fashionable streets. They later began to see more of each other until Edward's unexpected death in 1925. His mother had re- married but died undergoing an operation not long afterwards while my father, trained as a cavalry officer, was away on military manoeuvres.

Thus freed from family ties he embarked on what was to become a life dedicated to recording the seismic events that were to transform the 20thcentury, the social and cultural changes that provided the colourful backdrop, and the iconic personalities and the humble foot soldiers at the head and heart of it all. He was in England when war broke out and was unable to join his military unit back in Poland. Instead he became a war artist for the Allies and for Poland.

He was on every Front during WWII - the Arctic convoys, Russia in 1941, Burma and India, the Levant, China, Africa, Europe and the London Blitz where he was wounded, having been driven day and night around the burning city by his then girlfriend, my mother Marion Everall; she was one of the great film director Alexander Korda's actresses and a passionate political activist.

She had introduced him, a newly arrived yet already feted foreigner, to the cultural life of London: to the Café Royal crowd who met there at the weekends for brunch - Augustus John the painter, critic Cyril Connolly, firebrand Labour politician Nye Bevan, actor Michael Redgrave, Graham Greene, the writer - a wonderful coming together of politics and the arts.

They all became the subjects of great paintings and drawings by the charming and pushy newcomer to London's social world. My father had an extraordinary ability to penetrate everywhere - high or low society - British royalty, Apartheid South Africa, an Elvis Presley newsconference, Chilean Junta leaders, America's Black Panther inner circle. He created the first cover of Graham Greene's short lived but influential literary review Night and Day and had a book of his London drawings published within months of arriving in Britain.

His wider reputation began to form as Hitler invaded his homeland. Throughout the war he sent his dramatic and forensically accurate drawings back to Picture Post, the Illustrated London News and the News Chronicle. In the absence of television and the restrictions imposed on photographic reportage, Topolski's drawings were how many people in the UK saw the war. One woman wrote to thank the editor of Picture Post: she had heard nothing from her husband in eight months and had assumed he was dead; but she had just seen the current issue of Picture Post and there, in a drawing by Topolski, was her husband on board his ship, playing the spoons and she knew that he was alive. I am always surprised that Topolski is often left off lists of important war artists, but many consider him the greatest of them all.

My father accompanied the liberating troops crossing Europe and Germany; he drew the abominations of the Belsen concentration camp where, unusually, he took photographs as well, because he thought no one would believe his drawings.

He wrote compellingly in his autobiography 14 Letters about his horror at what he saw : 'This could be me, that, somebody close to me; thus I try to inject myself with responses. The piles of corpses, the multitude in extremis, are more than alien -horribly outside my equipment of susceptibilities ...Indeed one is hard pressed to believe one's senses - immersed in stench, stumbling over bodies pulled by the legs into the open, passing among living ghosts, molesting one or doubled up in excrement.'

He drew the many thousands of Displaced persons (DP's), freed from Nazi internment, struggling to return home, and the soldiers with whom he travelled. His determination to bear witness was inflamed by these experiences and his life thereafter was dedicated to chronicling the human condition.

His images from the Nuremburg Trials - coupled with those from Belsen- provide some of the most searing and memorable records of man's inhumanity to man. Many of these were reproduced in his very personal Topolski's Chronicle, a broadsheet containing over 2,500 drawings, covering every possible variety of subjects and which he produced partly on his own printing Press, every fortnight, for over 20 years. It was a huge effort but one that was free of any commercial or bureaucratic restraints - the artist communicating with people directly through the medium of art. Nobody else has ever attempted anything of this nature.

According to the art critic Bernard Denvir - the Chronicle is a unique phenomenon in 20th Century culture: a personal record of events - better than a camera.' It constitutes what Joyce Carey the writer, described as - the most brilliant record we have of the contemporary scene seized by a contemporary mind.' The work was done with uncompromising vigour 'sometimes in a single picture, sometimes in a cascade of drawings.

Beginning in 1953 he sent these Chronicles to more than 2000 subscribers all over the world - libraries, individuals, schools, friends, the White House, 10 Janpath 'the home of India's Prime Ministers, to galleries and museums. My mother sold them on the street at 2/6d an issue. She also papered the walls of our home with them, and my sister and I grew up with them all around us - a vivid, and early constant, visual history lesson.

The original painting of the Nazi defendants at Nuremburg is in the collection of the Imperial War Museum.

During the next four decades after the war, there followed an unending series of major international events which my father covered with great energy, imagination, style and thoroughness - I hope you will please forgive me for yet another list : India at the end of the British Raj, and then travelling all over the country as a guest of Pandit Nehru, the first Prime Minister, and his daughter Indira Gandhi - the first woman Prime Minister - at Independence; Mahatma Gandhi, Pakistan's first leader Muhammed Ali Jinnah; the French in Vietnam and then the Americans; Africa during independence - 'the winds of change', as Prime minister Harold Macmillan described it; Mao Tse Tung's Cultural Revolution in China; Civil Rights in America - the Black Panthers, Martin Luther King, the Chicago Democratic Convention in 1968; Apartheid South Africa; the Rev Ian Paisley and troops in Northern Ireland; May Day parades in Moscow for CBS Television; South America - Topolski was there for all of it.

His whole creative career though was based in, and flowed from, London.

He established his first London studio in Little Venice overlooking the Grand Union Canal in Paddington, a cosy group of 4 studios around a central garden. He painted there throughout the 1940's and entertained, with my mother Marion, artists, writers, politicians and students - a rich cultural environment into which I was born as the War ended.

Here, he threw a party for Picasso who was shunned by the British elite for his communist stance. Prince Philip was a regular visitor, eager to enjoy the delights of bohemian life. But it all came to an end when a local council jobsworth functionary decided that the studios should be demolished in favour of a public lavatory and small park. No amount of appeals from the leading figures of the day including Harold Macmillan, Lord Eccles and others could change the lumpen planners decision. Topolski and the other three artists were evicted and he became studio-less for the next few years.

In 1951, he was commissioned by architect Sir Hugh Casson to paint a mural for the Festival of Britain' called 'Cavalcade of the Commonwealth',a magnificent 50 foot long, twenty foot high painting celebrating the soon- to- be- dismantled British Empire. He created it in an arch beneath Hungerford Bridge in Waterloo. (the painting was later transported to Singapore where it was displayed for ten years at the Victoria Memorial Hall before being returned to Britain. )

My father found the aqueducts, warehouses and railway sidings of the South Bank, then a rough industrial landscape just across the river from the Houses of Parliament, and minutes away from central London, completely seductive and he decided it would be the perfect place to base himself. With the help of Lord Eccles, the Tory Minister of Works, he was granted a lease for an arch next to the newly built Royal Festival Hall. (Tories he reckoned could get things done quickly, bypassing protocol, while Labour tended to be hide bound by rules and best practise involving long frustrating delays.)

This studio arch was to become the nerve centre of his operation for the rest of his life. From here he would head off on commissions and journeys around the globe and then return to create his paintings, his books and his Topolski's Chronicle.

The Studio also quickly became a cultural salon, open on Friday afternoons for visitors from Poland, art students, friends, writers, passers by, Presidents, tramps, Royalty, celebrities, lovers and Prime ministers. At other times he offered his studio space to rehearsing theatrical companies and dancers, as long as he could draw them at work. He loved this constant flow of young people especially, and they valued his friendship and advice.

The studio was a magical space: a bed and sofa in one corner were surrounded by overflowing bookshelves; behind were a small kitchen area, shower and lavatory; then a huge printing press and paintings, drawings, prints and papers piled high, hanging form the ceilings and leaning against the walls - sometimes soaked from occasional floodings. He needed to close off the arch from the elements and he secured the end windows from the imposing Royal annexe to Westminster Abbey, built for the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth.

In time he acquired one of the lead-roofed Towers on top of Whitehall court directly across the river, following his separation from my mother and leaving the family home in Regent's Park. This was where his great collaborator George Bernard Shaw had lived and from this eyrie he was able to survey the whole city, along the Thames from Big Ben to St Pauls and the City beyond, with Whitehall, Hyde Park and the West End behind him to the north and west. Topolski at the heart of his beloved London.

He had a permanent arrangement with the National Theatre to attend all their first nights, sitting always in the front row aisle seat. On one occasion, drawing furiously, the leading actor came to a grinding halt, complaining of a constant scratching noise - Topolski's restless pencil. My father agreed to stop drawing - but once the show had got going again, he furtively took up a softer leaded pencil and continued to draw.

And then there was his panoramic Memoir of the Century mural, a huge visual autobiography, housed just a few arches along from his Hungerford Bridge studio on the South Bank, acquired in the mid 1970's. It is a distillation of all the many thousands of drawings he had created - he called them 'the fodder' - into one epic 600 foot long, 15 to 20 foot high painting - a Bayeux tapestry for our times.

'The Memoir,' he wrote, 'is a summimg up: ...it evolves naturally out of accumulated and overflowing testimony... wherever there was change afoot and where the world was trying to reshape itself. Experiences, understood or enigmatic/on the spot drawings/to and fro associations/dreams. Never documentation of events unwitnessed.' It requires, he said, the viewers' 'freewheeling imaginings'.

While it is global in scope and subjects, the Memoir also explores London and the rich and changing cultural life that he saw around him - theatre, fashion, politics, punks and hippies, ceremonies - the Coronation, Churchill's funeral, Royal weddings, down and outs, policemen, the Eton Harrow cricket match, the Derby, the Boat Race, Chelsea pensioners, the Changing of the Guard and the Cliveden scandal of the Profumo/Christine Keeler affair - there was nothing that did not capture his imagination and his astute eye, nor escape his pen, his pencil, or his paint brush. The combination of technical excellence and scale was unmatched by any other artist.

It took him the final 14 years of his life to complete the Memoir, and we have just restored it at a cost of £3 million. It is there now, free and open to the public - his gift to the nation for future generations. It is a vivid tour of our recent past - a historical visual record of the 20th Century. He was painting it still, at the age of 82, three days before he died of a heart attack in 1989 just as the Berlin Wall came down, bringing an end to communism in Europe. Ironically 28 years earlier he had taken his family to visit Poland for the first time and we drove across into East Berlin in 1961 as the announcement came that the wall was to be built.

But at this crucial moment in history, an event he would most certainly have attended, he was in hospital for tests and was demanding a sketch pad and pencils to draw the Houses of Parliament across the river from his bed at St Thomas's.

Let me say a few words about the Topolski way of working - exemplified by a six month adventure we had together. In 1980 - nine years before his death, - we embarked on a journey through South America - the only part of the world, apart from Australia, that he did not know. 'Don't go Feliks' , said his great friend Marek, fearful for Feliks's well being in his mid seventies. - Daniel is trying to kill you.' - We had negotiated a deal to do a film for the BBC, and also a book about our trip - about our mutual re-discovery after having pursued separate paths for many years; and also to gather material for an exhibition back in London of his drawings and paintings and my photographs.

An abiding observation he made during the trip was that he had finally felt able to relax in old age, in the embrace of his son. No longer driven by competitive instinct, he was happy to be supported and led, leaning, literally, on my shoulder, as we wandered 16,000 feet up in the Andes at Ticlio pass and the Machu Pichu ruins, and then later explored the Amazon forest, all the time while he was suffering from a gammy leg.

He seemed overwhelmed by this moment of self-discovery - although once returned to London he was back to his old combative, competitive self, challenging, full of vim and ever productive.

The 6 month trip itself was a wholly instructive experience. Our travelling routines were quite different: I should say here that I too was a passionate traveller - writing books and articles and working in television and radio. We had though slightly different priorities: he liked to go to a place, to settle and then circle, gathering in experiences and people before moving on to another place, while I loved the journeys in between, on the backs of trucks or in old rickety buses, the adventures, the distances travelled and the people I met en route.

Our instruments of visual recording were of course also very different: his modus operandum was ideally to be driven slowly down a street, sketching while barely looking down at the drawing, taking in the whole panorama 'something that a camera could never achieve. By the time we reached the end of the road, the life of the whole street was there on the page.

The very act of drawing too was an easily understood activity. In contrast to my photography his sketching was social and inclusive while my camera was aggressive, intrusive, and excluding. Crowds would gather, delighting in the way the image developed on the page, recognising the subjects - some of them their friends - in the milling throng.

Connections and friendships were spontaneously and warmly made. Taking photographs - that word 'taking' being the operative word, my way of recording things - was a much less friendly inclusive act. My father drew as others breathed. It was an inescapable part of his existence. He worked so quickly - hardly looking down to see the image taking shape on the page - and then back to the Studio to do big paintings inspired by the drawings.

Occasionally, I watched him painting some of the Memoir murals- often not even referring to the drawings at all. He had a photographic memory - he knew precisely what he wanted to paint. He didn't really need the drawings to paint by - it was all there in his head. He painted Martin Luther King's face from memory, while a television crew filmed him. It was done in a few minutes, without using previously made drawings that he had done years earlier of the great man, having breakfast at our home in London.

His hatred of received ideas meant that any time spent in his company was always fruitful. He offered a unique perspective, an unexpected view. Flying over the Amazon I remarked bitterly on the bare expanses of land, denuded by loggers and farmers, destroying the forests. 'Oh you and your politically correct views - what I see are vast endless forests stretching far off to the horizon.' When I was in hospital for many weeks, after a year long trip through Africa and India, he came to visit daily. 'What are we going to talk about?' he said - not wanting to waste time on polite inconsequential chat. We agreed that he would tell me his life story - episode by episode, day by day.

He slightly spurned - downplayed perhaps is a better word - his great ability as a draughtsman; it came almost too easily for him. He always sought out the toughest challenges. And he wanted recognition as a painter - oils, huge canvases - that was where great painterly reputations were made. That was how an artist was remembered. So his epic Memoir of the Century is a magnificent monument to that ambition. Yet he was also producing evocative paintings all his life.

The wide range of his style and his materials evolved throughout his life and matched the scope of his subject matter: early caricature and drawing as a student artist in Poland; penetrating drawings of the war years; old masterly paintings in oil done during the late 1940's, like these Polish refugees coming into Africa, Shaw, HG Wells; then his style changing - more impressionistic , use of guache, ink, charcoal, water colour and if you can believe it - Dulux oil house paint which he used for much of the Memoir. And throughout all of this time, he was producing many, many drawings, also changing in style - sometimes depending on where he was - or how inspired he was by where he was.

His portraits could sometimes be difficult for his subjects to deal with, although it is clear that he invariably established a powerful empathy with them as he worked. Edith Sitwell the writer was one. He heard that she was upset by his painting of her for the Harry Ransome collection, done from the drawings he had made for her Face to Face interview. He was mortified and wrote a long letter explaining that he had no intention to mock or caricature her but that he drew honestly and sincerely what he saw. After a while she wrote back to say that on reflection she had come to like the painting and went on to explain why it had upset her. Her parents had tried to correct a spinal, hump - a back deformity - by enclosing her for eight years as a child in a metal frame. The image had reminded her of that awful period. She invited him to visit. 'Please come for sherry.'

Aldous Huxley's sister believed that Topolski's portrait had so upset him that it had led to his death soon afterwards. Huxley was, it must be said, very, very old and very ill. The Harry Ransome centre had expected portraits similar to the full length painting in oil of George Bernard Shaw that they had acquired from Alexander Korda in California; but the images they got were in a different style, in guache using a more powerful, almost 'caricature' approach - exploring behind the sitter's preferred façade. The portraits are fiercely uncompromising - but always fair, objective though sometimes brutally frank. He was always his own man - never a flatterer.

His output was prodigious, and his energy was boundless. He spent many months throughout the 60's and 70's in America painting commissions, travelling the length and breadth of the country, constantly drawing: The Democratic convention in Chicago, Elvis Presley, John Kennedy, San Francisco, the Black Panthers, Bob Dylan, New York, Andy Warhol, Warren Beatty. He produced 24 books including his autobiography 14 Letters. He was renowned too for his seductive charm, but how he had time for so many dalliances with so many lovers is a mystery.

Curiosity for the unusual, his appetite for the downright bizarre and a sense of adventure too, led him to every nook and cranny, to society's teeming underbelly, to experimental theatre and burlesque. He loved contradictions, contrasts, juxtaposition: in his Memoir painting he pits the Black Panthers against President Lyndon Johnson, cheer leaders and stars and stripes Americana; The Queen's Coronation sits beneath Mao's China and alongside Castro's Cuba; a formally attired Lord Mountbatten towers above the new dolly birds of swinging London in the 1960's and next to the hippy commune members of the Eel Pie Island squat. Pope John Paul is set next to the garish abandon of the Alternative Miss World and London's gay life, which in turn is alongside Ian Paisley's Belfast, which is below Prince Charles practising his polo swings on an automated bucking wooden horse.

I do hope you will visit the Memoir - now called Topolski Century - in Waterloo. I know a group of you already has. You can even buy one of the remaining Chronicles or some prints or have a big colour poster made of one your favourite images in the Memoir.

I could go on - since his world experience was that of our century and has many twists and turns. However, I have given you a brief life story - perhaps a little short on incisive expert analysis and criticism, but that is not my field. I wanted here today to give you a taste of what made Topolski tick. I hope I have been able to convey something of that. Thank you for listening and I will be happy to answer questions.

© Daniel Topolski, Gresham College 2010

This event was on Mon, 22 Mar 2010

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login