Film Music: A certain train station

Share

- Details

- Transcript

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

David Lean's 1945 film, Brief Encounter, is a classic example of the way film can use music to drive the emotions of the audience. The film repeatedly returns to Eileen Joyce's recording of Rachmaninov's Second Piano Concerto, each time further entwining the viewer's emotions within the narrative. But how can this extravagant, extrovert music seem so perfectly adapted to the repression and guilt that surrounds the protagonists?

Download Transcript

A CERTAIN TRAIN STATION

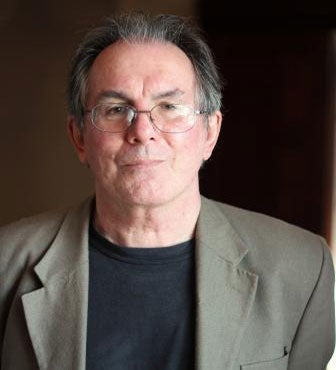

Professor Roger Parker

With this lecture I come to end of my series on Film Music. My thanks go out to all of you who've taken the trouble to come along, especially to those who have been regular attendees; seeing familiar faces in the audience is always encouraging, and - more specifically - has encouraged me to try to explore the area a little more consistently and coherently than I otherwise might have, had I been left entirely to my own devices. Of course, and as I made clear at the start of the series, I could never hope to do any kind of justice to my topic in the six hours available to me as Gresham lecturer; what's more, my awareness then of the already imposing and - worse still - ever-expanding corpus of film music, most of which I cannot ever hope to know, is even more intense now, as I near the end. I'm reminded, not for the first or last time, of a famous passage from German philosopher Walter Benjamin's mostly forbidding opus. Gazing on a painting by the expressionist artist Paul Klee (it's called 'Angelus Novus') and trying to evolve what he calls 'Theses on the Philosophy of History', Benjamin identified in the strange, bird-like figure that dominates Klee's canvas a symbol of what he called 'the angel of history'. He's what he said:

"His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing in from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such a violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress."

I think of this remarkable passage often when I wonder how to make sense of film music, which always seems to me a genre whose vast and ever-expanding wreckage is being hurled at our feet even as I speak.

As those who have been at past lectures will know, my strategy for coping with this frightening excess has been cautious and canonic. I've remained, for the most part, amongst classics of the genre: works comfortably ensconced in the past; works with commentaries and other kinds of scholarship to hold them firm in the teeth of the gale. When I've strayed from these classics, it has mostly been into what for me is comfortable home territory - into films of opera or into other explorations of what used to be called, in times of greater certainty, 'classical music'. To put this less gently, I've been indulging in what John Updike once called 'Hugging the Shore': fear of that storm blowing in from Paradise has prevented me from expeditions into the unknown - from trying anything like open water.

The caution of these voyages of mine has also been caused by something I mentioned in the very first lecture. As soon as I set myself to thinking about music as part of the experience of film-going, I became aware that I had best leave behind a good deal of my past training, my Professor-of-Music training. For one thing, all that mass of abstract technical language which we musicologists are so fond of using quickly came to seem hopelessly inappropriate. There are many reasons for this, but one is worth discussing here: it is that, when we deal with film music, in most cases we don't have a musical score on which to base our deliberations. It's no accident that musical analysis of the technical kind came into being at more-or-less the same time as musical scores began to be readily available as object of study: most of the resulting analysis is simply impossible without a score, and tends to be fully comprehensible only when you have the musical notation ready to hand, to refer to as you 'digest' (if that's the right term) the analysis. As I said, scores of film music usually aren't available, and - what's more - we have something else (and something pretty important) to be doing with our eyes while we're consuming it. So 'analysis' falls away. But then the question arises: what are we left with? what operations should we perform on the music?

These ruminations lead, in a roundabout way, to the subject of my last lecture, which is David Lean's 1945 film Brief Encounter, starring Celia Johnson and Trevor Howard. This is itself a famous document in British film history, often singled out for its strange combination of sentimentality and gritty realism, and has stimulated much learned and not-so learned commentary. [If you want to read further, then my recommendation would be Richard Dyer's excellent short book on the film (in the BFI Film Classics series), to which I owe a great deal in what follows.] But what principally attracted me to the film was that its use of music is both commonplace and rather unusual. The commonplace aspect is easily summarized, in that the music of Brief Encounter functions in ways that had by this time in film's history become classic: it is marshalled in support of what might be called 'structural' matters--it gives shape and a sense of connection to the central narrative, and helps to smooth over some of its necessary transitions; and it serves to concentrate and heighten emotional identification with the story - in particular to make us feel intensely empathetic with the central character of the story. Theunusual aspect is that Brief Encounter's music was not especially composed, but was borrowed from a pre-existing piece of 'classical' music: Rachmaninov's Piano Concerto No. 2, a work with its own structure, its own history and its own set of meanings. One of my main tasks today is going to be to explore how this use of pre-existing music works: what it adds to the film, and what potential problems it creates. But first, as always, we need some background.

Brief Encounter is based on a short play (one of a series) written by Noël Coward in 1936 and called Still Life. As it emerges in the expanded film version, it tells the story, mostly by means of flashback and with frequent use of a voice-over narrator, of a passionate, unconsummated but nevertheless tremendously guilt-ridden affair that occurs between two people who, before they meet by chance in a dingy railway station café, are both comfortably married and comfortably middle-class and (in the period's terms) comfortably middle-aged. She is Laura Jesson (played by Johnson), who comes into 'town' (a place called Milford) from her suburban home each Thursday: to go to the cinema, to change her library book at Boots and (one soon guesses) to add variety to a rather dull routine as devoted wife and anxious mother. He is Alec Harvey (played by Howard), a doctor still clinging to youthful ideals, whose Thursdays in Milford are spent assisting at the local hospital. The action takes place over seven consecutive Thursdays. Their first two encounters seem innocuous: on Thursday 1 Alec extracts some grit from Laura's eye ('Please let me look, I happen to be a doctor'); on Thursday 2 they bump into each in the street and exchange brief pleasantries ('I must be getting along to the hospital.' 'And I must be getting on to the grocer's.' 'What exciting lives we lead!'). On Thursday 3, though, lack of space obliges them to share a table at a local restaurant, after which they go to the cinema together. Back in the station, on their way to their respective homes, Alec asks 'most humbly' if they can see each other again next Thursday; after some reluctance Laura agrees. Thursday 4 is a debacle: Alec is delayed on medical business and they meet fleetingly only at the station on their way home again, having time to do nothing more than fix next week's appointment. Thursday 5 is prolonged and, in the end, passionate. They go to the cinema again (the main feature is calledFlames of Passion, but leave it to go boating. After a mishap (Alec falls in) they find themselves in a boathouse, admit to having fallen in love, and kiss in the underground passage leading back to the station. But Laura is by now wracked with guilt. On Thursday 6 they meet again, are discovered at lunch by some of Laura's acquaintances (more guilt), drive out into the country, and eventually agree that they must part. Back in Milford that evening, Alec asks Laura to come with him to a friend's flat, to which he has a latch key; she at first refuses and returns to the train station; but she changes her mind and goes back to the flat. No sooner are they alone together than Alec's friend returns unexpectedly: Laura escapes by the back stairs and wanders forlornly around town in the rain. She eventually drifts back to the station, where Alec has been waiting of her: they reiterate their decision to end the affair, Alec announcing that he means to take a job in South Africa. Next Thursday (Thursday 7) is their last. They again drive into the countryside; returning to the station, their final farewells are interrupted by a chattering acquaintance of Laura's. Alec leaves, and Laura comes close to throwing herself in front on an express train. But she pulls back and returns home. The final scene shows her with her dull, crossword-puzzle-solving husband Fred: sympathetic and apparently unaware of what has been going on, he tells her that she's 'been a long way away'.

As I've mentioned more than once in this series of lectures, bald synopses like the one I've just offered may seem neutral but never are. In this case, I have delivered (some of) the 'story' of the film, but I've betrayed hardly any of its crucial element, which is its texture: the way it narrates, the points of view it espouses, its contrasting colours, its battery of effects (visual, spoken, musical, other sounds). I've also hardly hinted at the fact that, precisely and ironically because of its self-consciously realistic, not to mention grimy, mise-en-scène, the film's first impression these days will be of something remarkably - perhaps for some even laughably - dated. In order to make a short-cut to this texture, a first extract is in order. I've chosen the latter moments of Thursday No. 3. Laura and Alec have had their first lunch together, they've been to the cinema, they've walked back to the station, and - somewhat dutifully, perhaps - have described their spouses to each other. Alec's wife, he says, is 'small, dark, and rather delicate'; Laura's husband is, it seems, the very model of an average Englishman gentleman: 'medium height, brown hair, kindly, unemotional'. They enter the station café, in which most of the action of the film takes place, and this is what transpires. Pay particular attention, if you will, to how the music functions, and try to work out - if this isn't too strange a request - whose 'side' it belongs to.

PLAY BRIEF ENCOUNTER: CHAPTER 7 START (26:06) TO 31:50

You may be interested to know that there's a US remake of Brief Encounter. Released in 1984, it's called - with what seems a desperate lack of imagination - Falling in Love, and it stars two of the cinema'sgalicticos of the period, none other than Meryl Streep and Robert De Niro. Let me tell you, though, that while the plot of Falling in Love is pretty much the same as that of Brief Encounter, Meryl and Robert don't (couldn't possibly) appear in scenes like the one you've just witnessed, which is in many ways typical of David Lean's film. This is not so much because of the minor signs of a bygone age, although there are plenty of those: the cups of tea and bath buns for 7d; or Laura's truly alarming cap at its rakish angle; or the fact that both the protagonists look so determinedly middle-aged; and so on and on. On the contrary, it's the larger issues that are so much more difficult to imagine occurring in a 1980s film. To take one example, there's the blunt obviousness of the class divisions, pointed up by the contrast of conversational style between the station manageress (played by Joyce Cary) and her assistant, and then between Laura and Alec. This is of course, partly a matter of accent and vocabulary: the difference between 'Din't you nivver go back?', on the one hand, and 'Is tea bad for one?' on the other; or the manageress's sadly inept and intermittent attempts to ape the vowels and speech patterns her 'betters'. But more insidiously there's the way in which this working class side-show (repeated several times in the film) is here clearly a source of condescending amusement for Laura and Alec (and was, one has to assume, intended to be so for the film's audience), even though the marital breakdown so straight-forwardly discussed - and, it seems, negotiated - by the manageress is shortly to become a source of agonized repression and crippling inaction for her middle-class listeners.

The other glaring anachronism of attitude is more subtle and - as we'll see - a good deal more conflicted. It concerns the gender roles played out by Laura and Alec. On the one hand, and although our heroine may strike agamine pose with that hat, Dr Alec's breezy overruling of her about the bath buns, and her infantilised behaviour as soon as he gets technical about his work, show us the extent to which women's roles have changed in the half-century since Brief Encounter was made. But, then again, it's not that simple. As I'm sure you noticed, towards the end of the scene there's a more fundamental point about this particular relationship between the sexes, one that seems to contradict this gender imbalance, and that turns out to be central to the texture of film as a whole. In spite of Laura's acquiescence and shows of pathos and incomprehension earlier in the scene, as the eyes meet and as Rachmaninov strikes up, it becomes clear that this particular affair-to-remember is unmistakeably seen from the woman's point of view. Recall how Laura in fact instigates the change of tone (from medical lecture to love affair) with her words 'You suddenly look much younger', and that as soon as the music responds to this change, the camera gradually closes in on her: it's as if that piano melody is not so much their music as her music: it may momentarily be banished by train noise and other sounds from the outside world, but it will, we feel, continue to scroll along in her head. And of course this filmic point-of-view - the fact that this is overwhelmingly a 'women's' film - is then made manifest by Laura's presence as the voice-over narrator. Alec may, in other words, seem to be in a dominant position, may seem to be making all the moves, but in terms of emotional depth and complexity, his is no more than a minor role in the drama.

That extract you've just seen also brings to the fore some of the difficulties that arise when, as here, the soundtrack is made up of pre-existing music. For one thing, unless the film is cut to the dimensions of the music, then there are likely to be moments when it needs to be rather drastically tailored to the dimensions of the film. Those with sharp musical ears will already have heard some of that tailoring: in particular a moment near at the end when Rachmaninov's tune didn't go on long enough for the scene, and had to be artificially continued by its repetition (in a different key, later in the movement) by the orchestra. By and large, though, this particular concerto is peculiarly well suited to filmic treatment: its three movements all linger on 'big tunes' that are remarkably similar and so can be used more-or-less interchangeably; and it has relatively little developmental writing (almost always difficult - because too attention-seeking - to fit behind visual events).

Even so, the music's relative lack of flexibility means that the film needs other kinds of sonic punctuation: sometimes (as we saw with those train sounds in the last scene) as ways of sweeping the music away; but at other times acting as a kind of alternative to musical markers. The most striking example of this begins in the opening scene of the film, which shows one version (a fuller, more emotive one will occur at the end) of the final moments of Laura's and Alec's last Thursday together, as they sit, shell-shocked, in the station café, nursing their cups of tea and waiting for the trains that will take them apart forever. As I mentioned, this parting is brutally interrupted by Dolly Messiter, a loquacious acquaintance of Laura's, who steams into the café at exactly the wrong moment. As so frequently in the film (it was a speciality of Noël Coward's dialogue) what is actually spoken in this scene is of almost no relevance: everything 'really' taking place is subterranean, communicated through subtle gestures, fleeting glances and camera movements. But this hidden choreography is brutally punctuated by what amounts to a veritable percussion section of train noises, each of them marking a further step in the impending separation. T.S Eliot's Alfred J. Prufrock measured out his life in coffee spoons; Laura and Alec measure theirs by means station sounds that are for them calls back to reality: the intrusive bell that three times announces a train's arrival, the rumble of approach, the announcer's sepulchral voice, the squeak of brakes, the guard's shrill whistle, the chug of departure and, sinister but somehow alluring, the approaching siren of the boat train. I'll start the scene a little earlier, to give you another chance to witness the working-class side-show (this time with the manageress joined by Stanley Holloway in full innuendo); and I'll let the scene play on until Laura and Dolly are finally settled in their train, where at last Laura can be released into her private world: a world heralded by an intense close up, her confessional voice-over, and - of course - the first, hesitant strains of Rachmaninov.

PLAY CHAPTER 2: 2:40 TO 7:30

Laura disappears into her private world, in spite of strenuous resistance from chattering Dolly.

As commentators have mentioned, the fact that the voice-over narrator inBrief Encounter is also its leading character (who is almost always accompanied by her own personal soundtrack) encourages some startlingly narrative rifts in the film: ones that might even lead us to doubt the authority of the tale being told. As good example is the aftermath of the moment when Laura and Alec first declare their love for each other. As I said earlier, this sentimental climax occurs on Thursday No. 5, after a boating trip in which Alec has got his feet wet. It takes place in the rather unlikely setting of a boatman's hut, somewhat clumsily justified in the opening stretch of dialogue, and improbably equipped with a stove to dry Alec's socks and - you've guessed it - the makings of that essential ingredient of all passionate love scenes, a nice cup of tea. The dialogue is not, to be frank, Noël Coward's finest hour. For one thing, the constant repetitions ('Tell me honestly, please tell me honestly' 'Not yet, not quite yet') sound terribly stagy and contrived, inevitably bringing to mind, at least for those of us of a certain age, memories of the 1960s BBC radio programme Round the Horne, in which similar, passionate exchanges (obviously modelled on Coward) would take place between Dame Celia Molestrangler and 'aging juvenile' Binkie Huckerback. But perhaps most estranging is that the entire conversation takes the form of a cross-examination: Alec feels the need to wring the tender confession out of Laura, almost as though she were in the dock; and the fact that she plays most of the scene on her knees in front of him, a position she took in order to lay his socks out neatly, does nothing to correct the sense of imbalance.

However, this scene, quite possibly because it's so dominated by Alec, takes place in silence, and is in some ways little more than a prelude to the extraordinary filmic virtuosity that occurs at its close. Alec's final words are 'There's no time at all', and immediately we hear that train bell again, calling them back to reality and home. Then, for the first and only time in the film, we actually see the bell (the instrument of their separation) clanging away, and immediately Laura and Alec are back in the station. They walk together into the tunnel which separates his train line from hers, and they kiss for the first time. The rumble of the train overhead merges with dissonant musical sounds; and then? But let's view the scene and how it continues.

PLAY CHAPTER 9: 42:20 TO 46:56

As you see, the transition out of that kiss in the tunnel verges on the surreal. The tunnel with its sinister shadows remains visually, and Rachmaninov has come up in volume; but suddenly we hear Laura's husband, long-suffering Fred, shouting over it, and - more surprising still - we see a ghostly image of Laura herself, seated in an armchair and seeming to stare at the tunnel from which she is emerging. Soon all is clarified: the music, we learn comes from the radio in their front room (which it does on more than one occasion: we must assume that Thursday night was forever Rachmaninov night on the BBC during these weeks) and, once Fred has settled to his crossword again, Laura can continue her reverie. But such disorientating switches of venue may also bring other questions to mind: if the scenes are all taking place in Laura's imagination, and if Rachmaninov's music merely comes out of the radio, then how reliable are the sense we witness? Is the entire story a fantasy, made up while listening to a romantic piano concerto in the living room? In the most important sense, of course, this line of questioning is idle: the entire film is, as I said earlier, steeped in Laura's point of view; whether it's real or imagined hardly matters.

My last excerpt, in many ways the most visually virtuosic, is a repeat version of their final parting, the one that we already witnessed at the start of the film. This constitutes the film's final last moments and, as is common with nearly all films, whether in 1945 or the present day, music is now almost a continuous presence, marking the fact that we should by now be thoroughly immersed in identification. And the entire scene is now unambiguously from Laura's perspective, with her voice-over commenting regularly throughout (indeed, with much of the other dialogue reduced to a muffled offstage) and with subtle changes of camera position and angle to mark her controlling presence. Notice again, though, that what I earlier called the station percussion section'the bells and whistles and sirens, the sounds of punctuality and authority and patriarchy and all things English - still inexorably mark the passing of time. They are stronger even that the music until the final moments, when Laura is back in her familiar armchair, and when Rachmaninov once again emanates from the radio. And pay particular attention to the very last shot of the film. Fred, 'medium height, brown hair, kindly, unemotional', finally puts down his crossword, goes across to sympathise and, finally, embraces her. There the film ends, with Laura in the last frame all but obscured by her husband. Is this a message, a sign that her adventure (whether real or imagined) has been crushed? I leave you to make your own judgement.

PLAY CHAPTER 14: 1:16:24 TO END OF FILM

It's time to close, and as usual there are many lines of enquiry left hanging. There is, for example, plenty more to saw about the film's historical context as part of a series of 'women's' film from around this period, many of which featured romantic piano concertos, both real and invented. How does Brief Encounter compare with other examples, such as Dangerous Moonlight (1941) with its 'Warsaw Concerto' or Love Story(1944) with its 'Cornish Rhapsody'? And what does the entire genre have to do with its historical period, with the fact that the Second World War dominated everyone's lives? And of course there is much, much more to say about the film's use of Rachmaninov, some of it perhaps even analytical. But that storm blowing out of Paradise is at our wings again, propelling us into the future. We must say a temporary farewell to this film, and indeed to film music generally.

©Professor Roger Parker, Gresham College, 06 May 2009

Part of:

This event was on Wed, 06 May 2009

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login