Quakers Living Adventurously: The Library and Archives of the Society of Friends

Share

- Details

- Transcript

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

Since the seventeenth century, members of the Religious Society of Friends - also known as Quakers - have often suffered for their beliefs and activities. In the early days, many were sent to prison. In later times they were prominent in the campaign against the slave trade. In the nineteenth century Friends such as Elizabeth Fry changed attitudes to issues of prison reform. Many Quakers have been active in parts of Asia and Africa and during and after both World Wars, they were heavily involved in humanitarian relief in Europe. These issues are all well-represented in the Library’s collections, which include printed books, archives, manuscripts and personal papers, pictures, photographs and museum objects.

This is the fourth in a series on Special Collections. The other lectures in this series are on the following collections:

Anatomy Museums

The Guildhall Library

British Architectural Library, RIBA

Lambeth Palace

Scotland Yard's Crime Museum

The Royal Horticultural Society's Lindley Library

St. Paul's Cathedral

Download Transcript

23 January 2013

Quakers Living Adventurously:

The Library and Archives of the

Society of Friends

David Blake

In this lecture I aim to do two main things:

To tell you something about the history of the Library of the Society of Friends over almost 340 years and to talk about some of the things Quakers have done, illustrating them with materials held by the Library.

But first I will talk briefly about the Society – say something about its name, tell you about its foundation and add just a little about what Quakerism is. However, I don’t consider myself to be an expert on this and the focus of this lecture will be very much on the library.

The Formation of the Society and its Early History

First, then, the name of the Society. The official name is the Religious Society of Friends in Britain, but to many people it is known simply as the Society of Friends. The word ‘Quaker’, which comes from the tendency of early Friends to shake as they worshipped, springs more easily off the tongue and indeed, if you look at our website you will see the banner ‘Quakers in Britain’. But Quakers - despite being very modern in many ways, witness their views on same sex marriage – seem to like tradition and you will hear the terms Quaker and Friend used all the time and interchangeably. Many names have been retained: the Chief Executive is still known as the Recording Clerk and one of the main bodies remains the Meeting for Sufferings. When you join the staff you are pointed to a little book called Quaker Speak.

The Society was founded in the middle of the seventeenth century, which was a time of great religious and political unrest. The man credited with being its founder was George Fox from Leicestershire, who left his village in 1643 at the age of 19 to travel around, trying to work out the spiritual side of his life. His travels are related in his Journal, which was published in 1694. The Library has seven copies of that edition, almost all of which have owners’ inscriptions.

Fox travelled north and in 1652 climbed Pendle Hill where he had a revelation ‘that there was a great people to be gathered’: this is generally acknowledged to be the moment when the Society was founded. He went on to Brigflatts in Cumbria, where he attended worship at the house of a local JP. The place has an important status in Quaker history and a meeting house was built there in 1675. The next day he visited Firbank Fell where he preached to more than a thousand people for three hours – a great gathering indeed.

A major part of his message was that it was possible for each individual to relate directly to God. There was no need for priests, no need for bishops and no need for pomp and ceremony.

Fox continued west to the small town of Ulverston, where he met Judge Thomas Fell and his wife Margaret, who owned Swarthmoor Hall. Margaret became a Quaker and Thomas seemed to have no objection to Fox using the Hall as his centre of operations. After Thomas died, George married Margaret in 1669. Swarthmoor Hall is considered to be the ‘cradle’ of Quakerism and is today a thriving centre of activity.

The growth of the Society and what it is about Today

The Society grew considerably and has become a significant part of Britain’s religious and political life, with a degree of influence out of all proportion to its numbers. There are currently 71 area meetings and 478 local meetings with just over 14,000 members. More than 8,000 others regularly attend meetings but are not members.

The Meeting for Worship, a period of silent contemplation which can occasionally be broken if members have something they wish to share, has a central place in Quaker activities.

The portrayal of Meeting for Worship in art has changed over the years, as some of the framed pictures in the Library show. Presence in the Midst by J. Doyle Penrose, which hangs outside my office, is a beautiful, very traditional work, showing a meeting at Jordans in Buckinghamshire.

Gracechurch Street Meeting House was one of the larger ones in the City of London, although it was closed in the 1820s when many Friends moved north out of the City to Stoke Newington. The third example is a modern depiction by the late John Perkin entitled Centering Down, which is the term used to describe the ‘technique of becoming quiet and still and silent’ at Meeting. John’s work certainly brings us up to date: there are those who hate it and those who love it.

In addition to meeting together, Quakers hold to a number of personal testimonies and try to live their lives according to them.

The first of these is truth and integrity in all your dealings with others.

The second is justice, equality and community and that means changing systems that cause injustice and working with those who are suffering from injustice.

The third testimony is simplicity. Quakers are alarmed by material excesses and have become very concerned about the unsustainable use of natural resources.

Friends are best known for the peace testimony, but more of that later.

So essentially Quakers live their beliefs: they don’t have a written creed. There is, however, a medium-sized red book, Quaker Faith and Practice, which provides guidance for Friends. It’s revised from time to time, with new sections being added to the web version.

The History of the Library

We’ve looked at some of the pictures in the Library. Now I will tell you something of its history.

The Library was founded nearly 340 years ago in August 1673 when one of its committees, the Second Day Morning Meeting, decided to acquire two copies of everything written by Quakers – and one copy of everything written in opposition to them, known as the ‘adverse’ collection. The minutes of that meeting exist, evidence that Quakers are good at keeping records. They have also been good at producing publications. For example, the Library has more than 4,000 titles published before 1700 of which more than 1,200 were produced between 1652 and 1660.

The collection was housed at the Society’s premises at Three Kings Court, just off Lombard Street in the City of London. It was clearly valued by the Society and in 1711 a proposal was made to purchase presses to preserve some of the books. Ten years later it was agreed “To have Baggs in Readyness, in Case of Fire, at or near Friends Chamber to Carry off the Books and Records kept there…”. The cost of those bags was 8s 4d for a dozen which, seems like quite a lot to me, but clearly library disaster plans are not a new idea.

The Library continued to grow, although the amount of ‘adverse’ material received declined and the policy on that had to be revived in 1730. In 1794 the Society moved to Devonshire House in Bishopsgate, not far from what is now Liverpool Street Station. The Library was allocated a room on the ground floor but it was used for other purposes as well and it soon outgrew that space.

In 1901 Norman Penney was appointed as the first Librarian and set to work to improve the library. He had three strong rooms for the archives and locked cupboards for books in meeting rooms, but no dedicated reading room. One was found in 1902, but as time went on, it began to be used for other purposes and books had to cleared away during meetings. The card catalogue was on wheels and had to be taken down to the strongroom every night.

In 1926 the Society moved from Devonshire House to Friends House, situated opposite Euston Station – where it remains to this day. As you might expect, we have early plans and photographs of the building, which was designed by the Quaker architect Hubert Lidbetter.

For the first time the Society had a proper reading room and specially constructed strong rooms, all of which are still used. The reading room was refurbished in the early 1990s, but it remains much as it was when it was opened. Indeed, Friends House is now a listed building and that restricts the scope for change. We are beginning to run out of space and will be looking at the options this year.

So what’s in the Library?

Having told you about its history and development, a quick look now at the contents of the Library, which cover something like 2.8 kilometres of shelving. I’ve worked there for just two years and don’t have a Quaker background, but I’ve been astonished by the breadth of the collections.

It’s important to realize that the Library receives no public funding and we rely heavily on the Society and on donations – not just the money which goes into our donations box, but also money for conservation work which is given to our BeFriend a Book Appeal.

Our most important material is the Society’s archives, which go right back to the middle of the seventeenth century and include the original minutes of the Yearly Meeting, the Meeting for Sufferings and committees on almost every topic under the sun. In addition to these national records we are also the official repository for Quaker meeting records from the London and Middlesex area, so if you want to find the records for the Peel meeting, for Ratcliff, for Horsleydown or even for the Bull and Mouth, you know where to come.

Alongside the archives of the Society are the manuscript collections – the non-official archives if you like - a mixture of personal papers, diaries, letters and the papers of various organizations associated in some way with Quakerism. The range of topics here is even wider than in the archives and there are thousands of collections of varying sizes.

We are in the process of producing an online catalogue and this should be available later this year.

The original policy of collecting two copies of books on Quakerism remains and we now have more than 80,000 titles. Our online catalogue now contains 60% of our holdings, including all the pre-1801 material. Much of our stock is not held elsewhere and we recently heard that we even have titles in Dutch which are not held by the National Library in the Netherlands.

We encourage Friends and researchers to donate copies of anything they publish and this brings us not just books and articles, but a large number of local pamphlets and leaflets, which are vital for us if we are to show the full picture of Quakerism in Britain today. We recently noticed that a Friend had given a local history talk in Pembrokeshire. We contacted him and he sent a copy of his talk and a guided walk to buildings of Quaker interest in Milford Haven, from which I learnt something I didn’t know - that whalers from Nantucket in New England were instrumental in developing Quakerism in that part of Pembrokeshire. The transatlantic spread of Quakerism clearly worked both ways!

We are also responsible for selecting the Quaker websites which the British Library features in the UK Web Archive. The Quaker collection currently has 267 sites which are archived several times a year. It’s one of the largest collections – certainly the largest religious one - and is featured on the Archive’s home page.

More than 200 periodicals are currently taken and we have non-current titles from many parts of the world. These include items such as the magazines of Quaker schools, membership lists of Quaker meetings going back to the middle of the nineteenth century – a great source for family historians – and complete sets of titles like The Friend, a weekly paper and Quaker Studies, the British academic journal in the field.

Other collections include more than 40,000 photographs, framed pictures, costumes and a wide range of museum objects. I won’t say more about these now because they feature in the rest of my talk.

The Adventurous Quakers

Some of you may be wondering where the title of this lecture came from. The answer is that it’s a quotation from George Fox who told his followers to ‘live adventurously’:

“When choices arise,” he said, “do you take the way that offers the fullest opportunity for the use of your gifts in the service of God and the community? Let your life speak.”

In other words, set an example and iive your beliefs. What you do and the way you treat others is more important than a written creed – and sometimes that can lead the individual into interesting situations, as we are about to find out.

But first I want to say something about the role of women in the Society. Women have always played a prominent role and 62% of current members are women. Quakers don’t have priests or bishops, so they don’t have to decide whether women can hold those positions.

I’ll give you four examples of prominent women.

The first one is the women of the Fell family. Margaret Fell, who as we know married George Fox in 1669, was a major force in early Quakerism. She was imprisoned twice and was a prolific writer, producing sixteen books. Many of her letters are in the Library as part of the Swarthmore manuscripts, a major collection of early Friends’ correspondence and she features in a forthcoming TV programme which made use of the library’s materials. Margaret’s daughter Sarah ran the Swarthmoor estate and her account book, which is held in the Library, is considered to be a very important social document of the time.

Fell and Fox encouraged the growth of women’s meetings within the Society and the records of many of the national bodies are held by the Library. In our London and Middlesex role, we also have the records of the strangely named Box Meeting, which was entirely composed of women and dealt with issues of poor relief.

As a second example, I will take the large number of women Quakers who travelled and produced diaries or published widely. Many of them preached, or travelled in the ministry, as it was called.

Amongst the diaries held by the Library are those of Elizabeth Yeardley covering the years from 1815-1820, Elizabeth Robson, who with her husband spent four years in America, Martha Gillett Braithwaite, whose 29 volumes of journals cover the period from 1842 to 1895, Catherine Braithwaite, who travelled in Europe in the 1870s, Sarah Lindsey, whose journals cover her travel in the Americas, the Pacific and Australia and Helen Gilpin, who kept an irregular journal in Madagascar from 1884 to 1887 and Margaret McNeill, who kept journals and diaries relating to her work in Germany with the Friends Relief Service.

The third example is Catherine Impey, from Street in Somerset – the home of Clarks shoes – who published the country’s first anti-racist newspaper Anti-Caste. So far as we know, the Library has the only complete set in the country.

The fourth example I’ve chosen is Tace Sowle, who took over her father’s printing business in 1695. She printed and distributed the works of George Fox, Margaret Fell, William Penn, and Robert Barclay. She was also the main printer of Quaker women's writings - more than one hundred works by thirteen different women - and she also did virtually all the routine business printing for the Society.

Sufferings: The Persecution of early and not so early Friends

Early Quakers such as some of these women developed a reputation as being leaders of God’s ‘awkward squad’ and many of them were persecuted for their beliefs or for the way in which they expressed their views. The Act of Toleration of 1689 eased the situation somewhat, but Quakers continued to be subject to confiscation of goods, fines and imprisonment for refusing to pay church tithes or take oaths. They were also excluded from public office and couldn’t attend Oxford or Cambridge until 1871. Many spurious charges were brought against them under the Vagrancy Act, which was intended for totally different situations. By 1660 more than 3,000 Friends had been imprisoned, put in the stocks or made to pay tithes in some way or other.

The Library has a vast quantity of published and unpublished sources on Quaker sufferings, described by one historian as an “embarrassment of riches”.

Friends were keen to record their sufferings at a local level and the originals are to be found in many record offices around the country. The details were also sent to London to the office of the Recording Clerk where they were listed in a series of 44 large volumes known as theGreat Books of Suffering - handsome ‘elephant’ folios, 23 inches tall and in some cases five or six inches thick.

They provide detailed accounts of sufferings and the individual persecutors were often named. The records are a wonderful source for social and economic historians and those researching local and family history, as well as historians of Quakerism. There are also the Original Records of Sufferings, consisting of original accounts of sufferings sent up to London by individuals or meetings during the period 1655 to 1766. Researchers may also use Besse’s book on sufferings, which covers the period from 1650 to 1689.

In an article in Quaker History Richard Vann has shown that Friends were keen to tell the world about their sufferings. “Scarcely,” he said, “had the first persecution befallen them than the first broadside rang out in response and published accounts of sufferings continued to appear at frequent intervals for more than half a century.” Vann shows that by 1709, 249 publications about sufferings had appeared.

At the same time, those who were opposed to Quakers were busy churning out tracts condemning them. These were often written in strong language and have titles such as Some few of the Quakers many horrid blasphemies, heresies, and their bloody treasonable principles, destructive to government or The painted-harlot both stript and whipt, or the second part of Naked truth, containing. A further discovery of the mischief of imposition, among the people called Quakers… .

A bibliography of these tracts was produced by Joseph Smith in 1879 under the title Bibliotheca anti-Quakeriana: it runs to about 500 pages and was based largely on our holdings.

Quakers and Anti-slavery

Another area where Quakers were up against the establishment was on the question of slavery, where they played a major role in the anti-slavery movement.

The origins of the Quaker testimony in this area can be traced back to George Fox who in 1657 wrote a letter of caution “To Friends beyond sea, that have Blacks and Indian slaves”. He visited the West Indies in 1671 and urged Friends there to treat slaves better. His views were published in London in 1676, in the book Gospel Family Order.

British Quakers expressed their official disapproval of the slave tradein 1727 but it was not until much later in the century that the lobbying became really intense – but Quaker actions were effectively the first lobbying activities in Britain for abolition.

In June 1783 London Yearly Meeting presented to Parliament a petition against the slave trade signed by about 300 Quakers. It’s particularly interesting because the names are all recorded in the volumes of the Yearly Meeting minutes, but were not retained by Parliament. Meeting for Sufferings also set up a committee to consider the slave trade and a separate group of six Friends met to plan the campaign, which included producing and circulating literature and lobbying Parliament.

In 1787 the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was formed and nine of the twelve founder members were Quakers. Thomas Clarkson – not a Quaker - took on the task of collecting every possible source of evidence. The Library is lucky to have Clarkson’s own copy of his study.

A major printed source is the collection of 37 volumes of 18th and early 19th century tracts against slavery, which totals over 600 items and includes tracts from leading abolitionists and local abolitionist societies.

In addition to the paper record, the Library has anti-slavery china with a logo showing a slave in chains. There is also a silk handbag with a picture of a woman slave with her child, which belonged to Rebecca Fox of Tottenham and is now on loan to the Museum of London.

Friends activities overseas and the Development of the FFMA

The second half of the nineteenth century saw Friends becoming more involved in work in other countries.

Rachel Metcalf was the first Quaker missionary and went to work at an industrial school in Benares in 1866. Later work in India included schools, orphanages and medical missions and by 1903 there were 34 missionaries, 42 native workers and 6 churches in India.

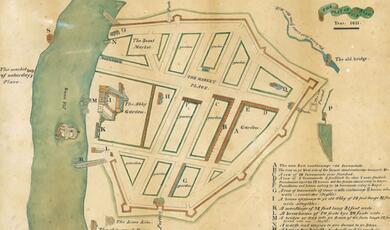

In 1868 the Friends Foreign Mission Association – the FFMA - was formed to co-ordinate activities in this field and the records are extensive, including the usual minutes of Committees, but also things such as maps and plans of properties in different parts of the world.

The Friends Syrian Mission, set up in 1874, was, at first, a separate organisation that became a part of the FFMA in 1898. Schools, a hospital and a dispensary were set up in Ramallah though this work was transferred to the New England Quakers in 1898. Another centre was Brummana in the Lebanon, founded by the Swiss Quaker, Theophilus Waldmeier, that contained an industrial school, schools for boys and girls and a hospital. The High School still exists today.

From 1886 the Friends also established missions in China, especially at Chungking in Szechwan Province, where they helped to establish the West China Union University in 1910; and in Ceylon in 1896. The Friends Ambulance Unit – of which more later – also saw service in China.

In 1897 Theodore Burtt and Henry Stanley Newman – who was editor of The Friend - went to Pemba, off the coast of Tanzania, to investigate the establishment of an industrial mission to provide employment and a place in the world for freed slaves. The Library has the records of this visit, together with Newman’s correspondence and press cuttings files. Great progress was made in clearing land, planting crops and helping the freed slaves to build a life for themselves and in 1909 a cathedral was built on the site of the old slave market. Activities were later scaled down owing to lack of funds, but Burtt remained there until 1931 and there was a presence until Tanzania gained independence in 1963.

Quakers in Madagascar

Another part of Africa where Quakers and the FFMA left their mark was Madagascar. In May 1867 three Friends – Louis and Sarah Street from Indiana and Joseph Sewell from Britain landed there, keen to do what they could to improve the life of the people.

The accession of Ranavalona II in 1868 led to the public recognition of Christianity and by 1880 there were 90 churches, each with a school and a total of more than 4,500 scholars. Two boys, Frank and Rasoa, came to Britain to attend the Quaker school at Bootham from 1871 to 1873. The establishment of a printing press in the capital in 1872 was a particularly important event.

There were regular articles about developments in journals such as the Friends Quarterly Examiner and others went to work there, including William Wilson, later secretary of the FFMA and Sewell’s daughter Lucy and her husband William Johnson. In 1890 the British Government agreed to recognise French interests there and several years of tension followed. During French bombardment of the capital in 1895, 483 people sheltered in the hospital which Wilson ran while shells and bullets fell around them. Later that year William and Lucy Johnson and their daughter Blossom were having breakfast when about 1,000 men arrived, many of them bearing arms. All three were killed.

Quakers continued to take an interest in the island and by 1950 the larger of its two Yearly Meetings had 286 Friends’ meetings with a membership of more than 6,000. Work continued in the pastoral and educational fields and a Madagascar Committee existed up to 1970. There are still links: for example, Barbara Prys-Williams and the Swansea Meeting founded the charity Money for Madagascar in 1986.

One interesting story to tell is about our copy of Thomas A Kempis’ The Imitation of Christ, one of our oldest books, published in 1488, which we received as a gift in 2003. It was William Penn’s own copy and later belonged to Joseph Radley, who worked for seven years in Madagascar for the FFMA. He resigned from the Society and became an Anglican, but later returned to Madagascar and worked with a Malagasy Quaker, Rabary, on the first translation of the book into Malagasy. This was published by the FFMA Press in 1928 and we received a copy with the 1488 edition.

Madagascar provides another interesting episode showing that we never know quite what will arrive when we receive new collections. These horns, filled with hair, teeth and nails are supposed to bring prosperity. They were presented to Olaf Hodgkin when he was an FFMA educational missionary from 1904-1920.

Elizabeth Fry and prison reform

I’m now going to return to Quaker activities in Britain. Those of you who have a £5 note will see that it bears a picture of Elizabeth Fry talking to prisoners in Newgate Prison. The Library was pleased to assist the Bank of England with the pictures.

Born part of the Gurney banking family in 1780 and later married to Joseph Fry, Elizabeth was appalled by the conditions in British prisons. She visited Newgate in 1812 and did what she could to improve conditions. For almost twenty years she regularly inspected convict ships to ensure that conditions were at least reasonable, and established a training school for nurses. On a political level, she campaigned for prison reform and the abolition of capital punishment. She became very well known not just in Britain but in many parts of Europe. I see that she appeared on a German stamp in 1952, many years before she appeared on a British one.

The Library holds a number of key resources for those interested in Elizabeth Fry. All but two volumes of her diaries are held, covering the years 1797-1833 and 1837-1845. Correspondence with her daughter Richenda and other members of her family and a collection of letters received by her throw some light on public opinion at the time. And then there is an autograph pass to Newgate Prison.

Quakers and poverty in the East End

As we’ve seen, some of Elizabeth Fry’s work took place in London, which was the venue for the Bedford Institute Association, one of the Quaker organizations whose records we care for.

Peter Bedford was a philanthropist who established a Sunday School in Spitalfields in 1849. It later grew to include work concerned with relieving poverty: assistance was given with meals, arrears of rent were paid, a kitchen for invalids was started and clothing clubs were organized. Sewing lessons were arranged and those taking part were able to sell what they produced. Others were trained for domestic service and some were relocated to Lancashire – or assisted with emigration to Canada.

Bedford died in 1864 and the Bedford Institute Association was established three years later. It expanded rapidly and by the end of the century had nine centres in parts of East London. The range of their activities was huge, including bands, temperance societies, lectures, entertainments, classes in sewing and elocution, meetings for mothers, clothing clubs, a savings bank, a library, gymnasium and a cricket club. Importantly, there was also a Medical Mission.

The organization survives in the East End to this day as Quaker Social Action and it recently won a Guardian charity award.

Quakers and Temperance

For some reason whenever you say the word ‘temperance’ some people think of the word ‘Quaker’. This isn’t so much the case nowadays, but in the nineteenth century it certainly was – which is rather strange when you consider that there were a number of breweries owned by Quakers. However, they were renowned as honest people who didn’t water down their beer and gave good measures!

The Friends’ Temperance Union was founded in 1852 when, to quote The Friend “…a meeting of Friends interested in the Temperance Cause was held at the London Tavern … when about 110 Friends sat down to a cold dinner”. One of those Friends was James Backhouse. It didn’t have a real corporate existence until 1877 and the Library has its records from that date.

The collection consists of the official records of the organization, including minutes, correspondence, printed items, notices, reports, press releases, financial papers, newspaper cuttings and newsletters There are also some very interesting posters produced by the organization and a large collection of lantern slides. A special cataloguing project took place three years ago, funded by the Wellcome Trust.

By the early 1960s the Union had extended its focus to gambling and sexual behavior and changed its name to the Friends Temperance and Moral Welfare Union. It’s changed again and is now known as Quaker Action on Alcohol and Drugs (QAAD). There are other relevant papers in the Library, including those of the Betting and Gambling Committee, the Opium Traffic Committee from 1881 to 1931, the interestingly-named Friends’ Social Purity Association and the Society for the Suppression of the Opium Trade.

Talking of alcohol reminds me of another story. Friends House is an alcohol-free zone: that was one of the regulations when it was built and it’s remained that way ever since. But as with most rules, there is one exception. Sitting down in the strongrooms is a bottle of port dating from the 1790s, which was given by John Gurney Bevan to John Brown, John King and John Brown junior when they were imprisoned in the Fleet Prison in London in 1797 for the non-payment of tithes at Haddenham near Huntingdon. It was presented to the Library by John Brown of Wisbech in 1898 with one condition attached – that it is not to be opened until the Church of England is disestablished. Who knows? The way things are, that may well happen sooner than many people think.

350 years of Working for Peace

I’m now going to turn to the area for which Quakers are perhaps best known – the area of peace. The Society is a pacifist church and this can be traced right back to 1661 when it produced its Peace Testimony, which included the statement that Friends “do utterly deny, with all outward wars & strife, & fightings with outward Weapons, for any end or under any pretence whatsoever.”

Over the past 350 years Quakers have put this into practice in many ways. I’ll show you some of these, with particular emphasis on the twentieth century.

But to begin with, just one of the many peace posters which have been produced by the Society, sometimes in association with the Northern Friends Peace Board, which is celebrating its centenary this year.

And a photograph to show you that Quakers are still making a contribution in this area, in this case the Ecumenical Accompaniment Programme in Palestine and Israel.

It’s almost a hundred years since the outbreak of the First World War and many organisations are preparing to mark the event. For Quakers it will certainly be a time to remember those who died, but looking back, the picture isn’t clear-cut. Quakers were divided: some decided that they should join up; some were absolutists and wanted nothing to do with the war – and many of those spent much of the war in prison; and some decided to play a role in the Friends Ambulance Unit, the FAU, which provided medical services on the Front Line.

The FAU was not an official body and certainly not all of its members were Quakers – in fact, in the First World War the proportion was less than half – but it was run by Friends.

Its achievements were quite considerable and at first there was a greater degree of co-operation with the French than with the British authorities. The FAU set up dozens of hospitals in France, took over hundreds of motor ambulances paid for largely by Quaker collections, manned dressing stations on the Front Line, gave 127,000 typhoid jabs in Belgium, fedand clothed refugees, started village industries such as lace making, distributed milk and purified water, managed recreation huts, carried 33,000 men home in its own two hospital ships, moved 260,000 sick and wounded men from the Front in its own motor convoysand another half a million in its four ambulance trains. In all, it spent £138,000 – the equivalent of £12.5m today.

The FAU was revived in the Second World War and saw activity in large parts of the world, including Finland, Norway and Sweden, the Middle East, Greece, China and Syria, India and Ethiopia, Italy, France, Belgium, Netherlands, Yugoslavia, Germany and Austria.

The Library holds the records for both First and Second World Wars – much more for the latter than the former - including personnel records which are of great interest to family historians, minutes, newsletters, including the original artwork for some and internal unit ones such as The Little Grey Book(for SSA 13) A train errant (for SSA 16), Lines of communication (for SSA 17), and Two years with the French Army...SSA 19(for SSA 19). There are also reports from the field, large collections of photographs and a number of personal diaries and accounts of service which have been given by individuals.

As its name implies, the FAU worked mainly in the medical field, but Friends were also active in other types of relief work. In the 1840s Friends were assisting people in Greece and in the 1870s they helped in the Franco-Prussian War. During and after the First World War they were active through the Friends Emergency and War Victims Relief Committee, the main history of which was written by Ruth Fry, and from 1933 to 1948 the Germany Emergency Committee gave considerable assistance to refugees. During the Second World War the Friends Relief Service operated in Britain, France, the Netherlands, Greece, Germany, Austria and Poland.

The Spanish Civil War saw more activity, with Quakers playing a big role in helping children to escape from the horrors of war.

Quakers win the Nobel Peace Prize

By the 1940s the Quaker record was substantial and particularly so for a relatively small body of people. This was recognised in 1947 by the joint award of the Nobel Peace Prize to the Friends Service Council, the body which co-ordinated British Quaker activities overseas and the American Friends Service Committee. The Prize was formally presented in Oslo to Margaret Backhouse (for the FSC) and Henry Cadbury (for the AFSC).

The Society had been nominated for the Prize as early as 1912, just eleven years after the award was founded. It had been nominated again in 1923, 1924 and 1936 and on each occasion the nominations had been influenced by Quaker relief work with the victims of war and famine. The medal is one of our treasures and is brought out every time Quaker meetings visit the Library.

Quakers and conscientious objectors

We’ve seen how Quakers provided relief and medical assistance. It’s also important to note that they have worked together with others on a range of issues. One of these was conscientious objection: they not only provided assistance to their own members but joined with other bodies such as the Peace Pledge Union in the Central Board for Conscientious Objectors, the CBCO, which was formed in 1939. Its role was to lobby the government, Parliament and the Press, and to run local advisory bureaux for COs all over the country.

Although it wasn’t an exclusively Quaker body, the Library has the records of the organization. It’s a pretty big collection, which is likely to be of special interest to family historians and includes substantial correspondence files about individuals, transcripts of some of the tribunal proceedings and a card index of about 7,000 Appellate Tribunal cases.

The Board's newspapers CBCO Bulletin, which ran from1940 to 1946 and The Objector, published from 1947 to 1955, have many articles about particular cases, although only the first is indexed.

Another item of special interest is the Winchester Whisperer, a clandestine newsletter produced by COs in Winchester Prison, written on toilet paper.

Quakers and the allotment movement

I’d like to finish with a subject very much to do with Britain in the early part of the twentieth century.

Friends were very concerned about the looming depression in the 1920s and in May 1926 appointed an Industrial Crisis Committee which was succeeded by the Industrial Crisis Subcommittee of the Home Mission and Extension Committee. Just eighteen months later, in 1928, that was renamed the Coalfields Distress Committee and in 1930 that was replaced by the Allotments Committee, which continued, surprisingly with the same name, for more than twenty years, until 1951.

The Clerk of the Committee – roughly equivalent to Chair – was Joan Mary Fry, who you may have seen on a Royal Mail stamp only last year – the first time, by the way, that the word ‘Quaker’ has appeared on a British stamp. Fry had been a prison chaplain during the First World War and championed many conscientious objectors at tribunals. After the war she was very involved with the Friends Emergency War Victims Relief Committee and she was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Tubingen.

In the 1920s Fry worked in the coalfields of South Wales, where she established food centres for the children of unemployed miners. In 1928 a project was started to encourage men to work on allotments, producing food for themselves and their families. At first the committee supplied free seeds, fertiliser, seed potatoes and tools – with a cost of ten shillings per plot. The committee gave £3,000 as a start-up and seed merchants and pit owners helped.

In 1930 the government of the time took over some of this work, but the government fell and the new one didn’t see allotments as important, which was a pity because by then 64,000 men and their families were involved. Joan Mary Fry was not to be defeated and her Committee decided to carry on the work.

In some ways, the following quotation from Fry’s Swarthmore lecture of 1910 – twenty years earlier - sums up the story presented in this lecture:

‘Quakerism is nothing unless it is a communion of life, a practical showing that the spiritual and material spheres are not divided, but are as the concave and the convex sides of one whole, and that the one is found in and through the other.’

Useful Information

Library of the Society of Friends

Friends House

173-177 Euston Road

London NW1 2BJ

The Library is open to all on production of ID with current address.

Tel 020 7663 1135

Email library@quaker.org.uk

Opening hours

Tuesday – Friday

10am – 5pm

Website

www.quaker.org.uk/library

Quaker Strongrooms – the blog

http://librarysocietyfriendsblog.wordpress.com/

Facebook

http://www.facebook.com/libraryofthesocietyoffriends

© David Blake 2013

This event was on Wed, 23 Jan 2013

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login