John Colet and Sir Thomas More: The Philosophers, The Archbishop and The Sultan

Share

- Details

- Text

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

In 1509 John Colet and Thomas More joined the Mercers' Company. This Symposium looks at these two key Tudor figures from an academic, political and religious perspective and place them in the context of their time.

This half-day event examined a range of topics including the birth of the Renaissance, early humanist theology and the linking of Colet and More to Sir Thomas Gresham's values.

This part of the symposium includes the following talks:

Dean John Colet & Sir Thomas More by Professor Tim Connell

The Philosophers, The Archbishop, and The Sultan: The Historical Circumstances that made the world of Colet and More by Dr Allan Chapman

Download Text

Dean John Colet & Sir Thomas More

Professor Tim Connell

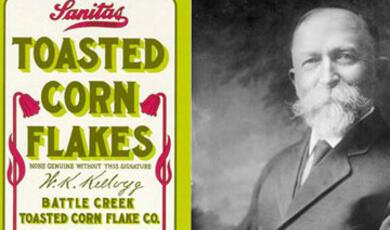

We are commemorating John Colet and Sir Thomas More this year because of their links with the Mercers' Company, which both of them joined in 1509. They were first-class City men: Colet was the son of Sir Henry Colet, who was twice Lord Mayor of London and, of course, he became Dean of St Paul's. More was the son of a judge, a student at Lincoln's Inn, and undersheriff from 1510 to 1518. He also lodged for four years with the Carthusians in the Charterhouse near the Barbican. But if Sir Thomas was a man for all seasons, then Colet was one of the greatest men of his age. The two were close friends (Colet was actually More's confessor) and they made a massive contribution to the times in which they lived, a contribution indeed which has survived to this day. More, of course, could add diplomacy, government service and the world of letters to his many attributes, not to mention his time as Speaker of the House of Commons, a highly respected position (in those days at least). Colet studied at Oxford, as did More, who was high steward for both ancient universities, so it is not surprising that he should hold strong views on education, as of course did Colet, whose great achievement of founding St Paul's School we are also recognising today. And More was a great proponent of a sound education, for girls as well as boys. His daughter, usually known by her married name of Margaret Roper, became not only a highly qualified scholar in Latin and Greek as well as theology, but she was also one of the first women in England to appear in print. She was also, may I add, a translator of great skill, who should perhaps be better known in her own right, and not just as someone who was determined to keep the memory of her father alive, and who indeed dealt with the critical final years of More's life with dignity, tact and courage.

More and Colet would have been great men in any period of history, so it is hardly surprising that they met and became friends with the other great spirits of the age. Of these, Erasmus must stand out most clearly, as his thinking on matters of theology was perhaps more advanced (and even far-reaching) than that of either the young scholar whom he met at Oxford (Colet) or the young lawyer (More) whom he met a couple of years later in London. He was introduced by his old tutors William Grocyn and Thomas Linacre, educationalists and thinkers who also merit greater recognition and esteem than I think is normally accorded to them. Also important was William Lilye, a pioneer of Greek learning (and author of a Latin primer that was to stay in print for three centuries) and who was to become the first High Master of St Paul's. The common denominator in all of this was the Renaissance, and Humanist thinking, which revolved around the study of Greek, with all the possibilities that this offered in terms of novel fields of study, the re-discovery of the Classics - and the impact that this would have on the Reformation and all their lives. Linacre is critical as he may have been the first scholar of Greek in England, and he actually taught Erasmus.[i] Lilye is also a key figure: slightly older than the others (he was born in 1468), he went on a pilgrimage to Rome and visited Rhodes on his way back. There he came into contact with the many Greek scholars who had been displaced by the capture of Constantinople in 1453. He then studied in Rome and Venice and so brought a wealth of learning back with him.[ii]

These men were living in an age of massive change and no little danger, a time when so much had been ground down by war and lengthy conflict: the Wars of the Roses and the fall of the Plantagenets were a recent memory, and Perkin Warbeck was not executed until 1499.[iii] Thomas More was even brought up in the house of a man who was a veteran of the wars himself.[iv] Not only was the system of government reeling from rivalry and Civil War (not unlike the Labour party today), but much of the old order was in decay with the rise of the trade guilds which affected commercial life as well as foreign relations. Change was in the air across Europe and beyond: the Portuguese were in the process of opening up trade to the East, thereby challenging the former hegemony of the Venetians, already greatly weakened and threatened by the expansion of the Ottoman Empire. The Spanish were making momentous discoveries in the West; Pope Alexander VI (himself a Spaniard and also known to history as the first of the Borgia popes) divided the world between Portugal and Spain in 1494 with his Treaty of Tordesillas. Peter Martyr d'Anghiera's De Orbe Novo was not published in full until 1530, but his first publication dates from 1511 when he was made chronicler to the Council of the Indies. Bartolomé de Las Casas, the Dominican friar who informed the world of the suffering of the Indians with his Breve Relación de la Destrucción de las Indias ('Brief Account of the Destruction of the Indies'), was pivotal in creating the Black Legend of Spanish cruelty in the New World, and which was pounced upon by Protestant states as proof of Catholic iniquity.[v]

This heady and seemingly endless range of new discoveries and intellectual challenges in a period of unprecedented change had an inevitable impact on the position of the Catholic Church across Europe: Savonarola was executed for condemning corruption in the Church in 1498; Luther's 95 Theses appeared in 1517, at about the same time as Ulrich Zwingli became the driving force behind Protestantism in Switzerland. These trends may perhaps be seen as the culmination of a process going back to the Czech theologian Jan Huss who was burned at the stake in 1415, not to mention the longstanding history of the Lollards in England, who had been persecuted since the time of Henry IV. [vi]

A key element in the growing ferment for change was the advent of printing. The spread of new ideas was undoubtedly helped by the speed with which ideas could be communicated, and it is perhaps no coincidence that Geneva became a centre for religious change as well as printing. In England, the key issue was the translation of the Bible by John Wycliffe into English as far back as 1382, and more importantly for the era of More and Colet, the Tyndale Bible of 1526 [vii]. It is of particular significance as it drew on both Greek and Hebrew sources, in much the same way as the great Polyglot Bible of Cardinal Cisneros at Alcalá de Henares is printed with Aramaic, Latin, Greek and Hebrew in parallel columns.[viii] Colet himself began to translate parts of the New Testament from the Greek, which he then read from the pulpit at St Paul's Cross to crowds which were said to number 20,000. This brought him into conflict with his own bishop Richard Fitzjames and at one point there was even concern that he could be charged with heresy, though this may have been triggered more by his unpopularity for attempting to reform the day-to-day running of the cathedral than any deeper matters of theology.

More, it should be remembered, was no mean translator himself. In fact, he came to prominence at an early age with a masterful translation of Pico della Mirandola[ix]. However, as Chancellor he relentlessly pursued heretics and in particular those who were responsible for the clandestine distribution of Tyndale's Bible, and he engaged in bitter disputes with Tyndale in matters of theology. Both men published accusations and refutations in fiery language (at times almost literally, considering the fate of some of the people caught with the Bibles). More's bitter opposition to heresy and fundamental change in the Church may seem strange in the light of the more moderate views expounded in Utopia, where freedom of conscience is tolerated. However, it would appear that More could not in all conscience abandon the old ways and he viewed both dissent within the Church and conflict between Christian kings with equal concern because of their threat to stability and the established order. This outlook perhaps harked back to folk memories of the recent wars and the suffering of so many people on the Continent of Europe in the name of religion.

John Colet did not live long enough to have to face that dilemma. He died in 1519 of the sweating sickness, but not without having seen the successful launch of his school, which had widespread support, ironically perhaps, as it supported the New Learning, encouraged the study of Greek, and laid the foundation for the many great schools which were to emerge in the sixteenth century. It is worth reflecting briefly on how he (and indeed, any of us) might react to a situation in which there was no option to take sides or even make a stand. What would any of us do if politics in this country came to the point where UKIP and the BNP were the only parties we could vote for? It is a dilemma which may perhaps be summed up by Foxe's Book of Martyrs on the one hand and, on the other, the canonisation by Pope Paul VI in 1970 of the Forty English Martyrs.[x] Someone to admire in this context is a near contemporary of both Colet and More: John Feckenham, the last mitred abbot of Westminster Abbey to sit in Parliament. He was confessor to Mary Tudor, and yet was offered the Chair of St Augustine by Elizabeth. He refused and was kept under palace arrest by the bishops of Winchester and Ely and eventually was placed in the Tower. Under Mary he interceded on behalf of some poor Protestants whose private beliefs had clashed with affairs of State - and while in the Tower he ministered to ordinary people in Cheapside and Holborn. He was as sincere in his faith as John Fisher who was martyred as Bishop of Rochester and who (like More) refused to sign the Act of Attainder, and he was no less a theologian than Cranmer, Latimer and Ridley, who all died for their beliefs.

Colet could have found himself in the same august company, but the pressure for change was not so strong at the time of his death that he might have been forced to make a stand. He was, of course, a courageous man, who dared to preach before Henry VIII on the topic of just and unjust wars shortly before war was declared on France in 1513. He undoubtedly disapproved of the slackness and venality of much of what he saw around him, though he was by no means alone in deploring that. He was a first-rate theologian himself and passionately attached to his church, however much he deplored its shortcomings at the time. His was a desire for reform (however radical) from within, which is why he was a close friend of Erasmus. The two actually went on a pilgrimage together to the tomb of that other great political English saint, Thomas à Becket at Canterbury, and another distinguished member of the Mercers' Company. (How the Mercers came to have quite so many saints in their ranks is a mystery to some of their fellow liverymen, it must be said, though to maintain a balance they have probably had more than their fair share of sinners...)

Either way, both More and Colet were outstanding in an era which spawned a large number of great men who were able to rise to changes hitherto unforeseen. Some rose to prominence, others died in disgrace. But they made their mark on English history and created a legacy for others to follow and even emulate. They also did the City of London proud which is no mean feat, and they both remain a credit to their livery company, which is principally what we are here to commemorate today.

Closing Remarks

We have set out today to commemorate two great men. We have looked at the age in which they lived, which set their horizons and which formed their beliefs and moral values.

It was in many ways a unique period, when events in places as remote as Constantinople and the Indies had an unimaginable impact on Europe at a time when political changes and social pressures were moving inexorably towards a more modern world, albeit one which would be rent by the divisions which were apparent even then, and which may still, tragically, be seen to this day. The set ideas and world order of the Middle Ages were left behind and thinkers, theologians and the political elite had to grapple with ideas, concepts and realities which had hitherto not been imagined, like the idea that the Earth might even revolve around the Sun.

We are becoming more aware today of the role of Islam in preserving the Greek legacy and early learning. It also built on it in keys areas such as Mathematics and Astronomy. Knowledge was there to be found and built upon, often through the medium of language: in Spain via the School of Translators of Toledo, where Jews, Christians and Moslems learnt to study and work together, providing Europe with access to long-lost texts and incentives to thinkers as diverse as Peter Abelard and Roger Bacon. Latin, which had held a prime position via Church and State since Roman times, remained the language of Science up to the foundation of Gresham College, where lectures were given in Latin to allow foreigners to understand them, and both Leonardo and Isaac Newton wrote their notes in Latin (sometimes backwards so as to confuse their rivals). Greek provided insights into whole new worlds of learning and drew together the greatest minds of the day. The sheer excitement for those young Renaissance graduates in Oxbridge and London is easy to see even now, the dangers which lay ahead of them only too clear to us today with the benefit of hindsight. Their legacy remains in their writing, their contributions to education and learning, and so they should be an inspiration for those of us who still try to make a contribution today.

Bibliography

J Arnold (2007) Dean John Colet of St Paul's. IB Tauris.

J Guy (2000) The public career of Sir Thomas More. Harvester.

J Guy (2008) A daughter's love: Thomas and Margaret More. Fourth Estate.

R Norrington (1983) In the shadow of a saint: Lady Alice More. Kylin Press.

F Seebohm (1869!) The Oxford reformers: John Colet, Erasmus and Thomas More.

J Trapp (1991) Erasmus, Colet and More: the early Tudor humanists and their books. University of Chicago Press.

G Wegemer & S Smith (eds) (2004) A Thomas More source book. The Catholic University of America.

Note: The Guildhall has a large number of titles on Thomas More and slightly less on John Colet, published over a wide period of time. There is also the Alfred Cock collection of Moreana, which was brought together in the nineteenth century, with some additions in the 1960s and 1970s. My thanks, as always, to Jo Wisdom for his assistance.

© Professor Tim Connell, 9 June 2009

[i] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Linacre

[ii] See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Lilye. (My reliance on Wikipedia here shows the lack of other suitable material on them...)

[iii] See 1066 and All That for a succinct explanation of this episode.

[iv] John Morton was a supporter of the Lancastrian cause, and became not only Archbishop of Canterbury under Henry VII but also (perhaps ironically) Lord Chancellor. He was an early sponsor of Thomas More.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Morton_(archbishop)

[v] The account was not published until 1542, and not in English until 1583, when it became known as Las Casas' Horrid Massacres. However the Laws of Burgos (1512) and the New Laws of 1542 provided ample evidence of the upheavals arising from the period of Discovery and Conquest. See http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h1120.html for some interesting articles.

[vi] Henry's law De Comburendo Heretico was passed in 1401. See 2 Hen. 4 c.15. The same Law forbade the translation of the Bible into English.

[vii] You can view a colour facsimile of the Tyndale Bible at:http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/sacredtexts/tyndale.html The British Library has one of the only two copies to have survived of the 18000 copies which were distributed secretly.

[viii] The full Bible appeared in 1517. There is an original version in the library of The Queen's College Oxford.Cisneros is viewed with some suspicion as he was a leading figure in the Spanish Inquisition.

[ix] More also published a joint translation with Erasmus of the Roman satirist Lucian, in 1506.

[x] See the Oxford Book of Saints, available on-line athttp://www.highbeam.com/The+Oxford+Dictionary+of+Saints/publications.aspx

Foxe's Book of Martyrs was re-published in the course of the sixteenth century. This and other works were produced by John Daye, who is known as the master printer of the English Reformation.

Part of:

This event was on Tue, 09 Jun 2009

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham College plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login