Literary Deans

Share

- Details

- Text

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

The Deans of St. Paul's include a significant number of literary figures among their ranks. Apart from famous names such as John Colet and John Donne, there is a founder member of the Royal Society, a friend of Izaak Walton and the Gloomy Dean himself. And how many Deans have pubs named after them?

Download Text

LITERARY DEANS

Professor Tim Connell

[PIC1 St Paul's today]

Good evening and welcome to Gresham College. My lecture this evening is part of the commemoration of the tercentenary of the topping-out of St Paul's Cathedral.[1] Strictly speaking, work began in 1675 and ended in 1710, though there are those who probably feel that the task is never-ending, as you will see if you go onto the website and look at the range of work which is currently in hand. Those of you who take the Number 4 bus will also be aware of the current fleeting opportunity to admire the East end of the building following the demolition of Lloyd's bank at the top of Cheapside. This Autumn there will be a very special event, with words being projected at night onto the dome. [2] Not, unfortunately, the text of this lecture, which is, of course, available on-line.

So why St Paul's? Partly because it dominates London, it is a favourite landmark for Londoners, and an icon for the City.

[PIC2 St Paul's at War] It is especially significant for my parents' generation as a symbol of resistance in wartime, and apart from anything else, it is a magnificent structure. But it is not simply a building, or even (as he wished) a monument to its designer Sir Christopher Wren, who was of course a Gresham Professor and who therefore deserved no less. St Paul's has been at the heart of intellectual and spiritual life of London since its foundation 1400 years ago. [PIC3: Old St Paul's]

And why deans? The role of dean is pivotal in the daily life of a cathedral. He is responsible for leading the cathedral in its mission and ministry, representing the cathedral in its engagement with the wider community. He is also a member of the Bishop's senior staff, with a variety of responsibilities across the diocese. Given the nature and location of St Paul's the role of Dean is particularly important, and the post has therefore attracted some interesting characters down the ages.

[PIC4: St Paul's Interior]

So why literary deans? You might imagine that writing comes as part of the job for most clerics, who at one time might have been the only literate people in the wider community. Even today, they might be expected to write sermons, prayers, hymns and even contribute to parish magazines. Historically they might have been expected to produce tracts, treatises and other controversial documents which, as we shall see, could cause serious problems for them. Epitaphs and odes might bring the poet out in them, and being educated men they might even have a range of intellectual hobbies and interests which place them firmly within the public eye. In the case of St Paul's, more than one Dean was appointed precisely because they were a leading literary or intellectual figure at the time.

I suppose I should digress slightly at this point and observe that St Paul's is not quite unique in its literary leanings. If I dare mention the phrase "Westminster Abbey" (the relationship between the Abbey and the Cathedral has been compared by some to Arsenal and Tottenham Hotspur, which could both be described as London football teams) they have a fairly good line-up of names too: they can field Lancelot Andrewes, chairman of the committee that translated the King James Bible (though he is actually buried in Southwark Cathedral); Richard Chevenix Trench the Nineteenth-Century philologist, and William Buckland who was not only a professor of Geology at Oxford but also a Fellow of the Royal Society. However, although I am sure they play in the same league, I hope to demonstrate this evening that St Paul's wins on points.

Of course, many educated people write for personal satisfaction or because they possess (or, more frequently perhaps) believe that they possess a talent. And others simply wish to contribute to learning in one way or another. The Church has historically been at the forefront of intellectual learning and debate and, since the days of John Colet at least, has wanted and expected to stay up with the times. Our very own Bishop of London, Richard Chartres, is no exception, as he not only has his own blog, but also runs his very own personal Index Librorum Bonorum for all to read. [3] I hope that includes the History of Gresham College which he co-authored with David Vermont in 1997.[4]

[1] See https://stpauls.co.uk

[2] See http://www.stpauls.co.uk/questionmarkinside/thequestionmarkinside.html

[3]See http://bishopoflondon.org/view_page.cgi?page=culture-index

[4] I get a mention on page 78.

In that respect the Bishop is simply continuing a long tradition, based not only on Mark 16 verse 15[5] and the lengthy tradition of speaking at St Paul's Cross, but he is also reflecting the longstanding connections between publishing and the vicinity of St Paul's.

I had a word with today's Dean, the Right Reverend Graeme Knowles, about this lecture and he modestly claimed not to be a man of letters himself. I nearly pointed out that in his previous role as Bishop of Sodor and Man he had a historical link with the Reverend W Awdry, whose Thomas the Tank Engine stories are located on the Island of Sodor, thus putting the Dean in the position of having been personal chaplain to the Fat Controller.[6] The Dean also expressed concern about approaching this subject in chronological order. He commented that when he visits parish churches, his heart sinks when the incumbent starts off by saying that the church was founded in the Seventh Century, as he then realises that they will only have got to the Nineteenth Century by lunchtime.

So let's begin:

There has been a Dean at St Paul's Cathedral ever since Ralph de Diceto in circa 1180. This could get worse as he is best known for his Abbreviationes Chronicorum and Ymagines Historiarum, which cover the history of the world from the birth of Christ up to 1202 AD, coincidentally the year of Ralph's death (so this could have gone on for much longer.)

He is a good starting point even so, as he is an example of the literary Dean who is writing about an aspect of his work that interests him. In that respect we can place him with the aptly-named Dean Church, who came into office (rather against his will) in 1871. [PIC5 Dean Church] It was a difficult time as he had to carry out restoration work on the fabric, face up to the Church Commissioners over funding, and update some antiquated practices among his own staff. Apparently he adopted a deliberately boring style in his sermons in order to discourage people from hoping for something longer.[7] In his own writing though, Church was much livelier. Apparently his letters (they were collected and published by his daughter) were written in a simple style and dotted with rather nice epigrams. We could all perhaps take note of his comments on style: based on his study of the Classics, he said that he "watched against the temptation of using unreal and fine words; that he employed care in his choice of verbs rather than in his use of adjectives; and that he fought against self-indulgence in writing just as he did in daily life".[8]

In terms of publishing, he went for biography, starting reasonably enough with St Anselm (the 11th Century Archbishop of Canterbury). From there he spread out to cover secular figures such as Spencer and Bacon in the popular Macmillan "Men of Letters" series, though he also wrote extensively, as you might expect, on theological matters, including a book on the Oxford Movement, which came out in 1891, a year after his death.

Church's near predecessor Henry Hart Milman (1849 - 1868). [PIC6 Hart Milman] actually had a serious career as a dramatist, writer and poet. In fact he became Oxford Professor of Poetry in 1821, three years after he had been ordained. Sir Robert Peel made him rector of St Margaret's Westminster (and therefore a canon in the Abbey) and he became Dean of St Paul's in 1849. His History of Christianity of 1855 was well received as were his works on the Classics. He was actually writing a history of St Paul's, when he died in 1868, so his son finished it for him.

[5]Go ye into all the world, and preach.

[6] The current Dean is only the second one to have served previously as a bishop. The other was Thomas Newton (1704-1782) who had been Bishop of Bristol.

[7]The Britannica discreetly says that the sermons had a quality of self-restraint.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_William_Church

[8] http://www.bookrags.com/wiki/Richard_William_Church

Henry Hart Milman wrote a number of hymns (such as Ride on! Ride on in majesty). These are of course no more than poems set to particular tunes, so perhaps we should turn now to the greatest poet, speaker and wit of them all: John Donne. [I almost started becoming chronological...]

[PIC7 Young Donne]

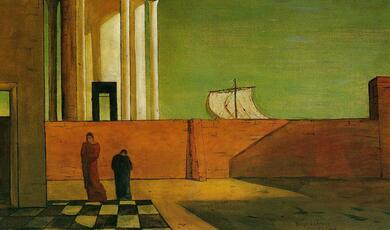

Donne is a curious character in many ways, and perhaps not at first sight a candidate for the deanery. Not only was he something of a gentleman adventurer in the Elizabethan mould in his early years. In 1596-97 he went on an expedition to Cadiz and the Azores with the Earl of Essex, which gave us those two splendid poems The Storm and The Calm which are reminiscent of the Rime of the Ancient Mariner: [PIC8 Gustave Doré]

Lightning as all our light, and it rain'd more

Than if the sun had drunk the sea before.

Some coffin'd in their cabins lie, equally

Grieved that they are not dead, and yet must die?[9]

Notice the complex scansion, something with characterises Donne's poetry in contrast to his sermons, which are best read out loud.

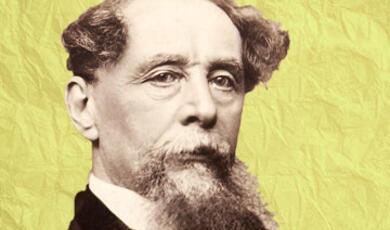

Donne was an educated man, having been to both Oxford and Cambridge (matriculating at the age of 11). A City of London man (his father was an Ironmonger) he studied law near here at Thavies Inn. But of course he was unable to take his degree as he came from an old Catholic family and so could not accept the Oath of Supremacy. His brother died in prison before he could be tried for harbouring a Catholic priest, his Mother was a great-niece of Sir Thomas More, and his uncle Ellis Heywood was not only a Jesuit but also secretary to Cardinal Pole. Izaak Walton, who wrote a touching biography of Donne, suggests that Donne did not opt for either Church until he had reached an age where he could make a decision. His choice of the Anglican church may well have been a reflection of the fact that most of Thomas More's direct descendants had spent some time in exile. Donne himself had travelled in Spain and Italy where, according to Walton, "he made many useful observations of those countries, their laws and manner of government, and returned perfect in their languages". He may simply have been preparing himself for a diplomatic career, but it is interesting to note that he wrote quite violently against the old religion and the Jesuits in particular. He may have reacted against the suppression carried out by Cardinal Pole who led the campaign against Protestants under Queen Mary. Or he may have judged it prudent with his family background to be seen to take a clear stance in those difficult times. It was certainly a wise career move as he obtained a position as secretary to Sir Thomas Egerton, who was Keeper of the Great Seal. It was nothing less than rash, however, to fall in love with Egerton's sixteen-year old niece, and marry her in secret when he was 29. [PIC9 Tower of London] He should have noticed that Sir Thomas was also Lieutenant of the Tower of London, and so imprisoned not only Donne, but also the priest who had married them and their best man. Although John and Anne were devoted to each other (she died in 1617, by which time she had borne him a dozen children, of whom seven survived) he must have regretted his rashness. According to Walton, he wrote "John Donne, Anne Donne, Un-Done". Ever the perceptive biographer, Walton relates:

"His marriage was the remarkable errour of his life [...] and doubtless it had been attended with an heavy Repentance, if God had not blest them with so mutual and cordial affections, as in the midst of their sufferings made their bread of sorrow taste more pleasantly than the banquets of dull and low-spirited people."[10]

[I wish I could write like that. I can't fish either.]

It was not until 1609 that the wrathful relative could be placated, which rather put Donne's career on hold. He worked as a lawyer, and was even a Member of Parliament for Brackley, but it was not until 1615 that he followed the urging of King James and entered the Church. It is rather noticeable that his writing can be seen to fall into three parts: his early romantic verse, his satires and epistles and his religious poems, with death as a recurrent theme. He is rather like his contemporary Robert Herrick whose Hesperides contains ardent poems to his many mistresses, whilst in his Noble Numbers (a slimmer tome) he displays the same emotional zeal in his religious verse.[11] [PIC10 Rosebuds]

Donne joined Lincoln's Inn in 1616, became a Doctor of Divinity at Cambridge in 1618. Again at James's urging, he spent two years abroad on a diplomatic mission with the Earl of Doncaster, attending on James's daughter Elizabeth of Bohemia in Prague. By the time he returned, the deanship of St Paul's was vacant and, again under pressure from James, he took the post.

Although he had been writing since he was a young man (and both the style and the subject matter are indicative of that) he produced a remarkable body of poetry, ranging from the profane and personal through to the sublime. His reflections on death make him the leading metaphysical poet, and if you visit the Cathedral you can see the celebrated monument of him in his shroud - based on a painting which he had commissioned only a few weeks before his own death.[12] [PIC11 John Donne in his shroud]

But in his lifetime he was better known as an orator and a writer of sermons (his most famous lines "No Man is an Island" and "Ask not for whom the Bell Tolls" come from here and not his verses). His best-known performances were given at St Paul's Cross, a location which played a key role in the public and devotional life of Londoners for several centuries, so it is worth looking at more closely in a brief diversion. [PIC12 St Paul's Cross]

It was literally a cross with a pulpit and a space for the great and the good. It is first mentioned in 1236 as a place where religious and political business was conducted.[13] It was here that the Folkmote met when the populace needed to be consulted on something, to be informed of changes in the world or (rather more frequently) was in a state of revolt. Bishops and even kings appeared here, as well as historical figures such as Simon de Montfort. The great religious topics of the day were debated here, from the days of the Lollards, through to the time of the Puritans. Heretics were brought here to recant, including James Bainham of the Stationers' Company who in 1532 was obliged to stand at St Paul's Cross carrying a candle and a bundle of firewood as a sign that he had recanted, having been found guilty of heretical opinions and connections with the books of William Tyndale.[14] John Donne could hold forth for an hour or more - the pulpit apparently came with its own hourglass - to crowds of literally hundreds of people.

Of course, bad weather (as at the Globe Theatre) reduced attendance, but people could always hear Donne preaching in more comfortable surroundings at St Dunstan's in the West, where he was appointed as vicar in 1624. Here he made friends with one of his parishioners, who shared (curiously enough) a love of fishing. He was, of course, Izaak Walton, who gave us the barmiest book in the English language (after Tristram Shandy, of course).

[PIC13 Front Cover of Compleat Angler]

Although he was born in Shropshire, Walton settled in the Square Mile and joined the Ironmongers' Company, though he actually rented a draper's shop in Gresham's Royal Exchange. He seems to have been a sociable man who moved in quite eminent circles, and was a friend of the poet George Herbert and the diplomat Sir Henry Wotton[15]. He also had a predilection for the Church: his first wife was a niece of Thomas Cranmer, his second wife was step-sister of the Bishop of Bath and Wells and is buried in Worcester Cathedral; Walton himself lived out his later years at the Bishop of Winchester's palace at Farnham Castle, and is buried in Winchester Cathedral. His Compleat Angler first appeared in 1653, and rambles on about rivers, fish, angling, odd botanical legends, and a pastoral view of the Lower Lea Valley and parts of Hertfordshire where he and his friends used to fish.[16] Donne's poem The Bait is celebrated for its first line "Come live with me and be my love". It goes on to develop a fishing metaphor skilfully:

[11] His poems include Gather Ye Rosebuds, Delight in Disorder and Cherry-ripe.

[12]It can be seen at http://www.luminarium.org/sevenlit/donne/shroud.htm

The monument still shows scorching from the Great Fire. It was one of the few monuments to survive.

[13] Different sources vary slightly on the first reference. Keene, Burns & Saint, (2004) St Paul's (Yale University Press). See also http://www.britannia.com/history/londonhistory/paulcross.html

[14] Foxe's Book of Martyrs of 1570 reports that he withdrew his recantation and was burned at Smithfield in April 1532. PWM Blayney (2003) The Stationers' Company before the Charter, 1403-1557. The Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers.

[15]He who gave us the aphorism "A diplomat is a man who goes abroad to lie for his country". Only strictly speaking, he didn't as he said something in Latin without the pun. See Walton's Lives page 38 in the Scolar Press edition, 1969. Wotton was subsequently Provost of Eton. For more on Wotton, see www.englishverse.com/poets/wotton_henry

Let others freeze with angling reeds,

And cut their legs with shells and weeds,

Or treacherously poor fish beset,

With strangling snare, or windowy net.

Let coarse bold hands from slimy nest

The bedded fish in banks out-wrest;

Or curious traitors, sleeve-silk flies,

Bewitch poor fishes' wand'ring eyes.

For thee, thou need'st no such deceit,

For thou thyself are thine own bait:

That fish, that is not catch'd thereby,

Alas! is wiser far than I.

However, it does make me wonder whether Izaak ever got the local vicar to go out fishing that often.

[PIC14: Rackham illustration]

I mention Walton at some length, as he is actually the third most re-published author in the English language (after the Bible and Pilgrim's Progress). The Compleat Angler has gone through over 500 editions and has not been out of print for over 350 years.[17] And with regard to this evening's topic (Literary Deans of St Paul's, just in case the subject matter has become a bit overgrown), The Compleat Angler contains a lengthy section in praise of Alexander Nowell, who was Dean of St Paul's for nearly half a century. It is worth quoting almost in full:

"A man that in the reformation of Queen Elizabeth [...] was so noted for his meek spirit, deep learning, prudence and piety that the then Parliament and Convocation both chose, enjoined and trusted him to be the man to make a catechism for public use, such a one as should stand as a rule for faith and manners to their posterity. And the good old man (though he was very learned, yet knowing that God leads us not to Heaven by many nor by hard questions), like an honest angler, made that good, plain, unperplexed catechism, which is printed with our good old service-book. I say, this good old man was a dear lover and constant practiser of angling, as any age can produce: and his custom was to spend, besides his fixed hours of prayer (those hours which, by command of the church, were enjoined the clergy, and voluntarily dedicated to devotion by many primitive Christians); I say, besides those hours, this good man was observed to spend a tenth part of his time in angling; and also (for I have conversed with those which have conversed with him) to bestow a tenth part of his revenue, and usually all his fish, amongst the poor that inhabited near to those rivers in which it was caught; saying often, "that charity gave life to religion": and, at his return to his house, would praise God he had spent that day free from worldly trouble; both harmlessly, and in recreation that became a churchman. And this good man was well content, if not desirous, that posterity should know he was an angler"?

[PIC15 AlexanderNowell]

Nowell's portrait at Brasenose College Oxford shows him with both his Bible and his fishing tackle. There is a note which says that "he died 13 Feb. 1601, being aged 95 years, 44 of which he had been Dean of St Paul's Church; and that his age had neither impaired his hearing, nor dimmed his eyes, nor weakened his memory, nor made any of the faculties of his mind weak or useless." Walton adds, "Tis said that angling and temperance were great causes of these blessings, and I wish the like to all that imitate him, and love the memory of so good a man."

[16] Much of it is actually plagiarised and eight chapters (including a section by the poet Charles Cotton on fly fishing) were added by 1673. It is elegiac in style with idyllic views of country life.

[17] The New York Public Library ran a major exhibition on Walton in 2003.

See www.nypl.org/press/2003/compleatangler.cfm

So his literary contribution was not only the Anglican catechism, but he was also an inspiration for one of the most hardy perennials in English Literature. Nowell is also celebrated for one more thing: the discovery of how to bottle beer. The story goes that he went fishing one afternoon, put some beer in a bottle with a cork in it, buried it to keep it cool, and then forgot about it. When he went back to his usual riverside spot a week later, he found it - and the beer was still fresh.[18]

Of course, alcohol and religion can mix: in the words of Hector Munro, "People may say what they like about the decay of Christianity; the religious system that produced green Chartreuse can never really die." [19]

By the same token, Nowell's contribution was matched by those deans who have managed to have pubs named after them. There is the Colet Arms in White Horse Road, London E1; Jonathan Swift does quite well with two, one in Butler's Wharf and the other in Lambeth. Canterbury Cathedral has presumably inspired a pub in Dunkirk (Kent) called the Dean and Chapter. Bishops fare slightly better: there is the Bishop of Norwich in Moorgate, the Bishop out of Residence at Kingston (on the site of the old Episcopal palace); but what can be said about the Bishop's Finger in Smithfield and the Mad Bishop and Bear in Paddington? This particular sign [PIC] commemorates John Incent, who was Dean of St Paul's between 1540 and 1545. He is remembered in particular for founding Berkhamsted School (which of course, eventually produced Graham Greene) but although there is a sign outside his house, it is not actually a pub![20] [PIC16 Dean Incent]

Thomas Ingoldsby comes in naturally at this point, as he has had a pub named after him in recent years in Canterbury's Burgate. He was not actually a dean, but in point of fact a Cardinal. St Paul's has two (the only ones in the Anglican communion) though they are, strictly speaking, minor canons.[21] And Thomas Ingoldsby was in reality a nom de plume - his real name was Richard Harris Barham, who was born in Canterbury in 1788 and who went on to study at St Paul's School. He went up to Oxford and returned to the Cathedral in 1821. He was a greatly respected and trusted figure who discovered a talent for writing doggerel verse, much of it, like the Ingoldsby Legends, based on old legends from Kent. [PIC17 front cover]

The Hand of Glory is poetically one of the best:

On the lone bleak moor

At the midnight hour

Beneath the gallows tree,

Hand in hand the murderers stand

By one by two by three.

And the Moon that night

With a grey, cold light

Each baleful object tips;

One half of her form

Is seen through the storm,

The other half 's hid in Eclipse!

And the cold Wind howls,

And the Thunder growls,

And the Lightning is broad and bright;

And altogether

It 's very bad weather,

And an unpleasant sort of a night!

Some of his work covers legends in the Square Mile. There is a splendid poem about Bleeding Heart Yard, where Lady Hatton is carried off by the devil as her husband Sir Christopher Hatton had taken over the Bishop of Ely's house.[22]

[18] http://www.beerhistory.com/library/holdings/raley_timetable.shtml

[19] "Reginald on Christmas Presents" in Reginald, (1904).

[20]http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Incent

[21] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/College_of_Minor_Canons#Cardinals

[22]http://www.exclassics.com/ingold/ingconts.htm

While those who look'd up could perceive in the roof,

One very large hole in the shape of a hoof!

Of poor Lady Hatton, it's needless to say,

No traces have ever been found to this day,

Or the terrible dancer who whisk'd her away;

But out in the court-yard -- and just in that part

Where the pump stands -- lay bleeding a LARGE HUMAN HEART!

Ingoldsby found favour with the reading public, and as he was married with children, he found the additional income very useful. As he commented on one occasion, "My wife goes to bed at ten to rise at eight, and look after the children, and other matrimonial duties; I sit up till three in the morning working at rubbish for Blackwood Magazine - she is the slave of the ring, and I of the lamp."[23]

Oddly enough, there is a further legend, that the Library at St Paul's is haunted by the shade of Richard Harris Barham. I can only imagine that he is a benign visitation.[24]

He was by no means the only Dean to look to popular outlets. William Ralph Inge, the Gloomy Dean, actually had a column in the Evening Standard between 1921 and 1946.

[PIC18 Dean Inge cartoon] He was known for his rather pessimistic and forthright views, hence the nickname. However, 16he also found time to write thirty-five books on Plotinus and neo-Platonic philosophy (as might be expected of a former Cambridge professor of divinity), and was a prolific writer of articles and sermons. In some ways, his views were quite modern (he was an early supporter of animal rights, for example) and he was critical of the more obscure verses of the Bible. As he once argued, "Do we really expect the working man to come to church to sing [...] such gibberish as the verse of the 68th Psalm beginning "Rebuke the company of the spearmen?" I am told that the correct translation of these words is "Rebuke the hippopotamus". Our churchgoers would sing this with equal unction if they had it before them, as fashionable ladies cheerfully sing the Magnificat, which is more violent than The Red Flag." [25]

This particular verse is quite celebrated, as a study of the original Hebrew would indicate that the verse should be translated as "the beast of the reeds", given that the word for "wild beast" may be read as "company" and the word for "reed" may be taken as "spear". It was presumably ill-advised to rebuke a hippopotamus in Ancient Egypt and we would do well to remember that fact.[26]

[PIC19 Bust of Colet]

Such fine points of erudition would have appealed to John Colet, who must rank as one of the greatest deans that the Cathedral has ever had. He came from an eminent City family (his father was twice Lord Mayor of London) and became a priest in 1497, shortly before he met the Dutch scholar Erasmus of Rotterdam - a friendship which was to alter both their lives. Colet lectured at Oxford and believed that the study of the Bible was critical and actually began to read the Bible in English to congregations of literally thousands of people in St Paul's, something which at the time was quite hazardous. He was, however, an eminent scholar in both Greek and Latin, a prominent public figure (he became chaplain to Henry VIII), and from an influential family, so he was at no risk of suffering the same fate as James Bainham.[27] He did, however, come into conflict with his Bishop, understandably perhaps as he disapproved of both priestly confession and priestly celibacy, and was critical of what he saw as idolatry in the Church. It is maybe not surprising that he was accused of heresy in 1512, but the charges were dropped. By then he had become a major figure as his father had died and left him a significant fortune, which he used to re-establish St Paul's School in 1509.[28] He took a close interest in the school, wrote the statutes and even some of the textbooks. He continued to give divinity lectures in the Cathedral, and was also famous for his sermons, one of which, the Convocation Sermon in 1512 contains the declaration that he was "sorrowing for the ruin of the Church". Although he uses the word "reformation" it is generally accepted that Colet was looking to the reform of the Catholic church, rather than any suggestion that there should be a break with Rome.

[23] www.exclassics.com/ingold/ingintro.com

[24] With thanks to Jo Wisdom, Librarian at St Paul's, for this and much other information.

[25] In an interview with Time magazine for August 28th 1950.

[26] I am indebted to my colleague Professor Ludwik Finkelstein for enlightenment on this point.

[27]See http://www.greatsite.com/timeline-english-bible-history/john-colet.html

[28] The cost was said to be in excess of £40,000.

[PIC20 John Feckenham]

But these were dangerous times for Churchmen, which leads me on to my final literary figure for this evening, John Feckenham. He was a leading figure who was the last abbot of Westminster, and indeed the last mitred abbot to sit in the House of Lords. He was at one time chaplain to Queen Mary, and yet was invited by Queen Elizabeth to become Archbishop of Canterbury. He took a degree in Divinity at Oxford in 1539, in the middle of King Henry's Reformation, and was actually at Evesham when that abbey was surrendered to the King less than a year later. He became chaplain to the Bishop of London, which led to him being incarcerated in the Tower by Thomas Cranmer, though his erudition was such that he was let out on a number of occasions to take part in public disputations.

He was released by Queen Mary on her accession in 1553 and became her chaplain and confessor. In 1554 he became Dean of St Paul's, a high profile position at a time when Cranmer, Latimer and Ridley were being tried for their lives.[29] He also attended upon Lady Jane Grey at her execution that same year. [PIC21 Execution] He was known to be unhappy about the brutality with which heretics were being treated, and interceded with Mary on more than one occasion to speak on behalf of poor Protestants, small people whose personal faith had unwittingly become entwined with the affairs of state.

Only a few years later, in 1558, Queen Mary died and this was when Feckenham was offered the See of Canterbury by Queen Elizabeth, but he refused to change faith and by 1560 was back in the Tower. He was effectively in prison for the rest of his life, although much of that time was spent under house arrest, or perhaps I should say palace arrest, as he was given over to the care of the Bishops of Winchester and Ely. After some years he went into a form of open arrest, during which time he dedicated himself to working for the poor in Cheapside and he even built an aqueduct for the inhabitants of Holborn. He was eventually moved to Wisbech, where he died in 1584 and is buried in the local parish church.

John Feckenham has his place in a lecture on literary deans because, although he did not write a great deal, and much of that is in the form of sermons and orations, he wrote one piece which caused him a great deal of trouble. This was the Declaration of such Scruples and Stays of Conscience touching the Oath of Supremacy which appeared in 1566, so it is worth noting him amongst tonight's people, as writers even today can suffer as prisoners of conscience, and the written word can be powerful in so many ways. I would also hope that John Feckenham can be remembered in this more ecumenical age as a man who risked his position by speaking up for poor Protestants on the one hand, and who turned down the highest position in the Church on the other because of his own beliefs. He clearly believed in faith by good works, lived a life of charity in what must have been difficult circumstances and seems to have earned the respect of all who knew him, regardless of their own position in those tumultuous times.

[PIC22: Modern Cathedral]

In a span of over 800 years, it is to be assumed that the post of Dean will have been held by a wide variety of people. There are, however, a number of common denominators: this has nearly always been a sought-after position whose incumbents are held in high esteem, even though some of those in almost every age have found themselves at odds with the state, higher authority or at the very least with their own Cathedral staff! It is almost to be expected that they will have been men at the top of their calling. Historically, most of them were University men with doctorates in Divinity and experience of teaching theology. In times when literacy was not widespread they were a focal point for writing and (more importantly perhaps) public speaking, hence the significance of sermons, orations and public debates. As educated men, they clearly had their own interests. A study of English cathedral clergy of the seventeenth century includes subjects such as Maths, Science, Logic as well as rhetoric, drama and language, following the mediaeval pattern of

[29] They were all burnt the following year.

See http://www.tudorplace.com.ar/Bios/Latimer,Ridley,Cranmer.htm

the Trivium and Quadrivium.[30] And it was Bishop Wilkins who proposed the creation of a universal language to the Royal Society. He is actually commemorated in the Ballad of Gresham College:

A Doctor counted very able

Designes that all Mankynd converse shall,

Spite o' th' confusion made att Babell,

By Character call'd Universall.

How long this character will be learning,

That truly passeth my discerning[31]

I suppose that we can include him here as, although he was Bishop of Chester, he was also for a time prebendary at St Paul's. This leads to one final point, that figures such as Colet and Donne led me to choose the title that I did. However, literary abilities (and even outpourings) have by no means been confined to the position of Dean. The poet Walter de la Mare was choirmaster at St Paul's, and the ebullient William Sparrow Simpson was the librarian as well as a sub-dean, and President of Sion College. [PIC23 Sparrow Simpson] His writings on the Cathedral provide a useful insight into aspects of its past, and his organisation and conservation of documents saved papers that might otherwise have been lost, so although not strictly speaking literary in his own right (though he did provide the libretto for an opera[32]) he really should be mentioned tonight.[33]

Doubtless too, could others, but while celebrating the topping-out of a great Cathedral, it seems to be only right that we commemorate the people who have worked and indeed flourished under its roof. [PIC24: St Paul's stamps]

PICTURES

1: St Paul's today

2: St Paul's at war

3: Old St Paul's

4: St Paul's interior

5: Dean Church

6: Hart Milman

7: Donne

8: Ancient mariner

9: Tower of London

10: Rosebuds

11: John Donne in his shroud

12: St Paul's Cross

13: Compleat Angler front cover

14: Rackham illustration

15: Alexander Nowell

16: Dean Incent

17: Ingoldsby Legends

18: Dean Inge cartoon

19: Bust of Colet

20: Feckenham

21: Lady Jane Grey

22: Cathedral modern view

23: Sparrow Simpson

24: St Paul's stamp

©Professor Tim Connell, Gresham College, 21 May 2008

[30]"Writings of English cathedral clergy 1600-1700" by S Lehmberg in Anglican Theological Review, Winter 1993, Vol 75 Issue 1.

[30]"Writings of English cathedral clergy 1600-1700" by S Lehmberg in Anglican Theological Review, Winter 1993, Vol 75 Issue 1.

[31] http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Ballad_of_Gresham_College

[32] "Crucifixion", with John Stainer, who was Cathedral organist.

[33] His titles include: Chapters in the History of St Paul's (1881), Gleanings from Old St Paul's (1889) as well as documents and papers from the archives.

This event was on Wed, 21 May 2008

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham College plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login