The Christian reticence of W H Auden

Share

- Details

- Text

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

Auden was arguably the most prodigiously talented of the great 20th century poets. When he recovered his Christian faith as an adult about 1940 this suffused all his later poetry. But it has been virtually ignored by critics. This lecture will explore the subtle ways in which Auden's faith emerges in his poetry and what was distinctive about it.

Download Text

CHRISTIANITY AND LITERATURE: THE CHRISTIAN RETICENCE OF W.H. AUDEN

The Rt Revd Lord Harries of Pentregarth

Stop all the clocks, cut off the telephone,

Prevent the dog from barking with a juicy bone,

Silence the pianos and with a muffled drum

Bring out the coffin, let the mourners come.

Let the aeroplanes circle moaning overhead

Scribbling on the sky the message He is Dead,

Put crepe bows round the necks of the public doves,

Let the traffic policemen wear black cotton gloves.

He was my North, my South, my East and West,

My working week and my Sunday rest,

My noon, my midnight, my talk, my song;

I thought that love would last for ever: I was wrong.[1]

That poem, which you may recognize from the film 'Four weddings and a funeral' suddenly put the name of W.H. Auden in the public circulation again, this time to a wider circle than it had ever been before.

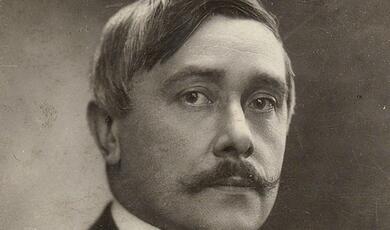

Auden, who was born in 1907 and died in 1973, and who published his first book of poetry in 1930 when he was hailed as a prodigy became thepoetic voice of those who came to maturity in the troubled 1930's. Although some believed, wrongly in my view that his later poetry lost some of its earlier power, he never entirely lost his position as the outstanding poet of the post T.S. Eliot generation.

During the 1930's Auden, like those associated with him such as Stephen Spender, Louis MacNeice, and Cecil Day Lewis, were thought of as politically committed and writing from the stand- point of the left. As Auden's obituary in The Times put it:

'To anyone who was young in the 1930's and troubled by the state of the world Auden's death will mean that something of their past has died too; for thousands of those who would now be called 'the involved' felt that Auden spoke up for them.'

In 1940 Auden returned to the Christian faith, which had left him when he was 15 and thereafter his poetry took a different turn. Critics are divided on the relative merits of his earlier and later poetry. What is more shocking is that so many have totally ignored or underplayed the fact that everything he wrote after 1940 is undergirded and suffused by his Christian faith. That has now been corrected, I am glad to say, through an outstanding work of dispassionate scholarship, Auden and Christianity by Arthur Kirsch.[2]

I am not speaking as a literary critic, and will not therefore be trying to assess Auden's poetic stature and legacy. I will be looking at his understanding of religion, as expressed both in his poetry and his prose, because I think this has some interesting and important insights for any thoughtful, cultivated person exploring the nature of religious faith today. However, I will just make two points very briefly in relation to his talent and where he stands in the development of 20th century literature. First, he was the most prodigiously talented of all 20th century poets. 'He possessed a technical virtuosity bordering on wizadry' as the literary scholar Katherine Bucknall put it. This was combined with an amazingly wide, often esoteric culture. Secondly, he recognized that the generation before his own, Stravinsky in music, Picasso in art, Joyce for the novel and T.S. Eliot in poetry, had made the decisive break with traditional norms and as he put it, rather modestly, he was a colonizer of that tradition.[3] The modernism of the previous generation had radically shaken everything up. Without going back on that Auden saw himself as crafting poetry in the most disciplined way possible. He did this in an amazing variety of forms. As the poet James Fenton has put it

He worked through every poetic form he could find. He invented (as far as English was concerned) a discursive style that could accommodate the language of prose and the concern of science.

Auden was brought up in a devout Anglo-catholic home by parents who did in fact practice what they preached, but like many other adolescents did not so much rebel against religion as lose interest in it at the age of fifteen in favour of going his own way to 'enjoy the pleasures of the world and the flesh'[4] Then he was caught up in the fun of living and loving, the hectic social life of Oxford, the heady insights of Freud and Marx and the excitement of being at the centre of the literary avant garde . So, what made him return to Christian faith? There are a number of factors.

First, a gradual recognition during the 1930's that the great problems being faced by the world were not going to be solved by political solutions alone. He had never been a fully paid up member of the Communist Party, always aware that there were other factors in addition to politics that needed to be taken into account, and the crisis of the 1930's sharpened this awareness. The rise of Fascism in so civilized a country as Germany shocked him and it posed the question about the grounds on which he would oppose it. So in his poem 'September 1st 1939', a poem that once again became famous when it was read and reprinted widely after 9/11 he wrote

I sit in one of the dives

On Fifty-second street

Uncertain and afraid

As the clever hopes expire

Of a low, dishonest decade:[5]

Secondly, when teaching in an English public school he had an experience that affected him deeply. One balmy evening in June 1933 he was sitting outside with some colleagues. They had not been drinking and they were not sexually attracted to one another. They were talking quite casually about everyday matters when, as he wrote:

'I felt myself invaded by a power which, though I consented to it, was irresistible and certainly not mine. For the first time in my life I knew exactly-because, thanks to the power, I was doing it-what it means to love one's neighbour as oneself... My personal feelings towards them were unchanged-they were still colleagues, not intimate friends-but I felt their existence as themselves to be of infinite value and rejoiced in it.' [6]

Thirdly, when negotiating with the Oxford University Press over a book of light verse, he met someone, Charles Williams, who struck him as unqualifiedly good. Again, as he himself put it:

'He was a saint of a man. It was nothing he particularly did or said, and we never discussed religion. One just felt ten times a better person in his presence.' [7]

Fourthly. There was the shock he felt when he was in Spain supporting the Republican cause, to find all the churches closed. Although he had been outside the church for many years, it surprised him how shaken he was. Then, finally, when he was in New York, where German films were still being shown before the Americans came into the war, he was even more shaken to find ordinary members of the German community in New York shouting 'Kill the Poles' [8]

I do not think there is anything very unusual about the kind of reasons that brought Auden back to the Christian faith in which he had been nurtured as a child. What is more interesting and decisive for his whole understanding of the nature of faith was what happened not long afterwards. When Auden arrived in America he fell in love with an 18 year old student, Chester Kallman. Before that he had always doubted if he would find true love, indeed if anybody could ever love him. All went well for 2 years and then he discovered that Chester Kallman was being unfaithful to him. Auden had the highest ideals of marriage, and had seen his relationship to Chester as a true marriage involving a total, lifelong faithfulness. But as he came, bitterly, to see, Kallman was temperamentally promiscuous, and was not prepared to have Auden on those terms. Auden himself, despite other physical affairs, continued to love Chester Kallman for the rest of his life and in a profound sense to be faithful to him. They lived together and they collaborated on work together. But this fundamental unhappiness at the heart of his life shaped his whole understanding of faith. In short, he came to believe, through great pain and grief, that his vocation was to love, even if he was not loved in the same way in return, and to be a poet. When Auden wrote about his return to faith he said this:

'And then, providentially-for the occupational disease of poets is frivolity-I was forced to know in person what it is like to feel oneself the prey of demonic powers, in both the Greek and the Christian sense, stripped of self-control and self-respect, behaving like a ham actor in a Strindberg play.' [9]

That is a strong statement and we can only guess at the anguish and rage that lies behind it.[10] But it had the effect of making down to earth love of neighbour fundamental to Auden's understanding of religion, beginning with love for his immediate, unfaithful neighbour Chester Kallman who caused him so much pain and grief.

Edward Mendelson, whose life's work has been collecting Auden's voluminous writings and himself writing about them has argued that love of neighbour was not only the overriding element in Auden's religion, but its sole element, and that he rejected the transcendent, vertical dimension.[11] That is wrong. It is always difficult to get the right balance between love of God and love of neighbour, and there is no doubt that for Auden love of God not only had to be expressed in love of neighbour but love of neighbour was the touchstone of that love. It was what in the end mattered, the only serious thing in life. But he did not think that the Christian faith amounted only to this. Undergirding it for him, first of all, was a sense of gratitude for existence. In a poem called 'Precious five', celebrating the five senses he wrote:

I could (which you cannot)

Find reasons fast enough

To face the sky and roar

In anger and despair

At what is going on,

Demanding that it name

Whoever is to blame:

The sky would only wait

Till all my breath was gone

And then reiterate

As if I wasn't there

That singular command

I do not understand,

Bless what there is for being,

Which has to be obeyed, for

What else am I made for,

Agreeing or disagreeing?[12]

Auden had a naturally happy temperament 'Even when one is hurt and has to bellow, still one is always fundamentally happy to be able to' he wrote, but he was hurt; Chester Kallman treated him like a door mat. He often faced the sky and roared in anger and despair, when people were not looking. Stephen Spender records sitting at a table with Auden and Chester Kallman when Chester got up and crossed the street to make advances to a young man. Auden went on talking but Spender saw that there were tears running down his cheeks. However, he knew that in the end there was no alternative but to bless what there is for being. 'Let you last thinks all be thanks' he wrote at the end.

In facing up to the predicament of humanity, and the need to love one another, he knew that he himself, like every other human being was part of the problem, and therefore that first of all he had to face himself without self-deception or illusion.

O look, look in the mirror,

O look in your distress;

Life remains a blessing

Although you cannot bless.

O stand, stand at the window

As the tears scald and start;

You must love your crooked neighbour

With your crooked heart.[13]

The idea of life as a blessing had an extraordinary richness for Auden because of the amazing width of his natural interests. His father was a doctor who became Professor of Public Health in Birmingham and who was also a keen amateur archaeologist. Auden's great love as a child was the rocks and landscape of Yorkshire, with its disused lead mines and one of his brothers became a professional geologist. He originally went up to Oxford to read science with a view to becoming a mining engineer and only there switched to English. There was almost nothing that did not genuinely arouse his curiosity and interest. So he wrote in one poem:

Let us hymn the small but journal wonders/ of Nature and of households.[14]

One of his best known and loved poems is called 'In praise of limestone' which does just that, relating the landscape with its different features to the human condition, and ending up:

When I try to imagine a faultless love

Or the life to come, what I hear is the murmur

Of underground streams, what I see is a limestone landscape.[15]

Many poets, in many different ways, have of course celebrated nature. Fewer have celebrated the wonders of households, but that also is what Auden did, most obviously in his collection called Thanksgiving for a Habitat in which he celebrates the different rooms in the house.

The extraordinary range of things in which Auden took a delight does I think bring out an interesting and important aspect of his understanding of the Christian faith which stands in contrast to another strand, represented for example by T.S. Eliot. Auden was, in both a denigratory and a celebratory sense, a worldly person. He drank a lot, he smoked heavily, he loved parties, he even gave a positive value to gossip. As he wrote:

'How often I have worked off ill-feeling against friends by telling some rather malicious stories about them and as a result met them again with the feeling quite gone. When one reads in the papers of some unfortunate man who has gone for his wife with a razor, one can be pretty certain that he wasn't a great gossip? Gossip is creative. All art is based on gossip? Gossip is the art-form of the man and woman in the street, and the proper subject for gossip, as for all art, is the behaviour of mankind.' [16]

It is not surprising that with this attitude to the world about him people found it difficult to think of him as deeply or seriously religious. But he was. Indeed he argued, rightly, that those who come across as serious are often in fact frivolous, and it is surprising to find that he regarded the sombre and portentous Eliot as in the end frivolous. Apparent frivolity, apparent light heartedness, and sheer enjoyment often cover up a genuine seriousness about life. Philip Larkin wrote about a later collection of Auden's poetry 'In some way Auden, never a pompous poet, has now become an unserious one.' In the light of that it is not surprising that he included virtually none of Auden's later poetry in his 20th Century Book of English Verse. Larkin could not have been more wrong. As Auden wrote:

'A frivolity which, precisely because it is aware of what is serious, refuses to take seriously that which is not serious, can be profound'

So, in a world of self-consciously serious people it is 'the smoking-room story alone' which ironically enough stands for 'our hunger for eternal life'.

As I suggested, the contrast with Eliot is an illuminating one.

Eliot, in his poetry, is an advocate of the via negativa. This suggests that the way to God is through a negation of all we think we know about him, through letting go all we hold on to for security, through loss and darkness. It comes across well in these lines of his from 'The Four Quartets', which are themselves virtually a quotation from St John of the Cross who is particularly associated with this way and 'The dark night of the soul' with which it is associated.

I said to my soul, be still, and wait without hope

For hope would be hope for the wrong thing; wait without love

For love would be love of the wrong thing; there is yet faith

But the faith and the love and the hope are all in the waiting.

Wait without thought, for you are not ready for thought:

So the darkness shall be the light, and the stillness the dancing.[17]

In short, to use words he uses a few lines later, we have to go by the way of ignorance and dispossession.

Auden, being a learned as well as a serious believer, would not of course have denied this, and he knew very well that all our human words and thoughts about God are in one inescapable sense, human projections. When it comes to God, we always make an image of what we most want or most fear. He used to ram this truth home to himself and others by talking about 'Miss God' in remarks like 'Miss God has decided to keep me celibate this summer'. That said, what is fundamental and characteristic about him is that he deeply appreciated and delighted in the world about him in its every aspect. Like the Roman write Terence he would have saidHomo sum;humani nil a me alienum puto, nothing human is alien to me. So, although Auden celebrated nature, he was essentially a city dweller, and it was city life that he rejoiced in both poetically and religiously, even to the smallest details of a dinner party. 'Tonight at seven-thirty', after describing many details of the ideal party ends

I see a table

at which the youngest and oldest present

keep the eye grateful

for what nature's bounty and grace of Spirit can create:

for the ear's content

One raconteur, one Gnostic with amazing shop,

both in a talkative mood but knowing when to stop,

and one wide-traveled worldling to interject now and then

a sardonic comment, men

and women who enjoy the cloop of corks, appreciate

dapatical fare, yet can see in swallowing

a sign act of reverence,

in speech a work of representing

the true olamic silence. [18]

Other Christian poets, notably Thomas Traherene, have celebrated thevia positive, but none, I think, have done it in such a bold, inclusive and, well, sheerly worldly way, as W.H. Auden.

Although the foundation of Auden's religion is rooted in his sense that the givenesss of life, despite everything, is a blessing, there is no doubt, as Edward Mendelson emphasizes, that love of neighbour is the essential touchstone for the reality of that religion. Duty is not a word that is in fashion today, but it was a key word for Auden and he was not embarrassed to quote the old Anglican Catechism that the Christian vocation is 'To do my duty in that state of life, unto which it shall please God to call me.' He believed that that the state of life to which he had been called was that of a poet, and his duty was to work on his talents to the best of his ability. He saw himself as a craftsman, in some ways like a carpenter, and he had no time for sloppy ideas of inspiration; and all his work, in such a variety of styles and forms, is indeed meticulously crafted. Although he had a heavily lined face and crumpled appearance and lived in some squalor, he was fanatical about timekeeping and could get irritated if meals were not served at the time expected. In a poem written for a friends marriage he recommends not only strong nerves but 'an accurate wrist-watch too/can be a great help'. In short he unashamedly championed the bourgeois virtues. Acknowledging that bourgeois society is in a mess he does not think that Dostoevsky will help us get out of it

'I would rather take the bourgeois hero, Sir Walter Scott, who worked himself to death to pay his creditors, than Alyosha or any other of Dostoevsky's seedy enthusiasts.' [19]

Paying your debts, keeping promises, turning up on time, observing the courtesies, improving your poetry- this was the more surprising side of a man who was known for his louche lifestyle, warm generosity and many good friends but which was all part of how he saw his duty to love God and neighbour. So duty is a key word. He kept going with Chester Kallman, because he continued to love him; because he had seen their relationship as a marriage, and because happiness for him was not in the end about pain and pleasure. As he put it:

'Happiness consists in a loving and trusting relationship to God; accordingly we are to take one thing and one thing only seriously, our eternal duty to be happy, and to that all considerations of pleasure and pain are subordinate. Thou shalt love God and thy neighbour and Thou shall be happy mean the same thing.' [20]

One of the sayings of Auden that has become quite well known is

'There is no such thing as a Christian politics, or a Christian art, or a Christian science, any more than there is a Christian diet. There is only politics, or art, or science, which are natural activities concerned with the natural and historical man.' [21]

This sentence occurred as part of a lecture at Yale Divinity School which was later published in the British journal 'Theology'. It is a serious, theologically wide ranging somewhat conservative piece, in response to a request to speak about the vocation of a Christian layman, and set within the framework of rendering unto Caesar the things that are Caesars.

He understands the fall of humanity, eating from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, as a desire for autonomy 'It is a desire to become one's own source of value, to become as God while still remaining a man.' This results in a condition of guilt and anxiety from which we try to escape by our own efforts through natural religion. 'Such efforts were bound to be self-frustrated since they were rooted in a self-contradictory desire to find an Absolute which at the same time should be controllable by man'. But with the coming of a revealed knowledge of God in Christ, this natural religion is longer needed, if it ever was. The job of the church, in particular the priest, is to transmit this unchanging truth, and for this task the particular human gifts of the priest are not strictly speaking relevant. The layperson on the other hand still participates in the wider world, perhaps mostly mixing with non-Christians, and in that world the things of Caesar have to be rendered to Caesar. This includes art, as well as politics and science. They belong to the historical and natural realm and the poet has to use such gifts as he has in that realm, without claiming the special revelation of God any more than a government can.

This is not the place to examine in detail what I regard as an over-sharp distinction in Auden's overall view as expressed there, but I will point out that in fact there is such a thing as Christian art, in the sense that in Western culture for example, until recently, much if not most art was inspired by Christian themes and images. The Christian faith has been an integral part of our culture and until the Enlightenment its beliefs seeped into and saturated music, poetry, and the visual arts. Of course it is right that a poet who had a Christian faith like Auden should not and would not claim that his poetic gifts and craft were more directly inspired, or more from God, than say, the communist Brecht. They both had to work with the talents they had been given according to the norms of their literary crafts. In that sense, the arts are a realm that belong to Caesar. But Auden not only felt accountable to God for the way he used his talents, but his faith shaped how he viewed the world and how he celebrated it, and sometimes, though not always, he used Christian imagery in this task. In that sense, there is a Christian art.

It is not surprising, given people's stereotype about what does and does not count as religious, that people should have had difficulty thinking of Auden as a religious man and have missed the all pervading religious dimension of his poetry. This hiddeness he made something of a creed. One of his poems is called '...The truest poetry is the most feigning...', which is a quotation from 'As you like it'. It celebrates the way that genuine poetry is bound to have a clever, artful, contrived aspect to it and ends up:

What but tall tales, the luck of verbal playing,

Can trick his lying nature into saying

That love, or truth, in any serious sense,

Like orthodoxy, is a reticence?[22]

The phrase 'Truth, in any serious sense, like orthodoxy, is a reticence' was a favourite of Auden.[23]

There were a number of reasons for his reticence. One is the traditional Englishman's reluctance to bring religion into polite conversation. This reluctance is particularly marked when it comes to what might come across as public display, as in politics, but also in the arts. Most recently that attitude was shown by Tony Blair, who said he did not talk about his religion when he was Prime Minister, for fear, as he put it, of coming across as a nutter. Given the suspicion of religion in the kind of intellectual circles that Auden moved, this motive would have been quite strong. So, when he wrote to T.S. Eliot, and said that he now shared Eliot's religious beliefs, he urged him not to tell anyone. Once, when someone came into the room and found him praying, he was extremely irritated. Then, there was the reason, already suggested, that true seriousness is so serious, that it often disguises itself with surface humour or lightheartedness. This was certainly so in the case of Auden, for people sometimes could not make out whether he was being serious or not. He often was, but people did not grasp it. Then, perhaps most important of all, when it comes to some of the big things in life, especially religious truth, words can only hint at what it conveyed, not tie it up in a neat parcel. Quite simply, neat parcels of religion, totally fail to convey the ultimate mystery of God, a mystery which is at the heart of Christian orthodoxy. As the great bastion of orthodoxy, with both a small and a large O, John of Damascus put it in the 8th century 'What God is in himself is totally incomprehensible and unknowable.' So all the words we use to convey this mystery will, as it were, be in inverted commas, will be metaphor or analogy. Another poet Emily Dickinson got it well in the 19thcentury when she wrote:

Tell all the truth but tell it slant-

Success in circuit lies[24]

So, as Auden ends his poem 'The Truest Poetry is the Most Feigning':

What but tall tales, the luck of verbal playing,

Can trick his lying nature into saying

That love or truth in any serious sense,

Like orthodoxy, is a reticence?

In those lines there are several other characteristic features of Auden's approach. Our nature is a lying nature. He had no illusions about himself or others. What tricks this lying nature into revealing the truth is 'the luck of verbal playing', a very modest way of talking about his massive poetic gifts.

The title of this series of lectures is 'Literature in a time of unbelief'. The 1930's, when Auden was the leading young literary figure, was a time of unbelief as marked as our own. It is true that the crisis of those times, followed by World War II, made religious faith a more serious option for many, as it had for Auden. Nevertheless the zeitgeist in literary circles in his time as ours is not on the whole sympathetic. So, as Emily Dickinson put it, 'Tell it slant' is often the only way in which an initial misunderstanding and resistance can be circumvented. But in Auden's case, this aspect was reinforced by the fact that in any case he understood the Christian faith as requiring us to celebrate this world in every aspect and in all its quirkiness.

One of the issues we all have to think about and which is not always easy to get right from a religious point of view, is the relationship between the pleasure and pain of life. If some religious people have given the impression of letting the balance fall on the pain side, Auden is the opposite. Although he knew real personal anguish, I am tempted to say, because he knew personal anguish, he was not prepared to offer an easy apologia for suffering. His poem 'Epistle to a Godson', is precisely what its title suggests, advice from Auden to one of his godsons. In it he asked what nourishment he as godfather should offer his godson for the Christian way and wrote:

Nothing obscence or unpleasant: only

the unscarred overfed enjoy Calvary

As a verbal event. Nor satiric: no

scorn will ashame the Adversary.

nor shoddily made: to give a stunning

display of concinnity and elegance

is the least we can do, and its dominant

mood should be that of a Carnival.

Let us hymn the small but journal wonders

of Nature and of households, and then finish

on a serio-comic note with legends

of ultimate eucatastrophe,

regeneration beyond the waters.[25]

Auden loved to mint neologisms, and here we seem to have one-eucatastrophe: but it is not difficult to work out its meaning. Catastrophe we know, an overturning bringing disaster. The Greek word eu meaning well, therefore suggests an overturning bringing its opposite, a good state of affairs. This is the ultimate outcome of the universe, in theological parlance, the eschaton, regeneration beyond the waters, but even here it is put forward in terms of 'a serio-comic note with legends' So, for him, in the end, all will be well, and with this hope in mind we are to do out job as well as we can 'to give a stunning display of concinnity and elegance is the least we can do', concinnity meaning skilfully put together, with the mood of carnival, and as discussed before, a hymn to the small but journal wonders of Nature and of households.

It should not of course be thought, because of that reference to Calvary as a verbal event the reality of Calvary as torture meant nothing to Auden. He took this and its implications for our understanding of human nature with the utmost seriousness. At one point he engages in a traditional Good Friday thought and wonders what he himself would have been doing at that time. He decides that at best he would be an ancient philosopher walking by and remarking to a companion how disgusting the crucifixions were, and why couldn't the authorities put people to death humanely, before continuing to engage in their fascinating discussion of truth, beauty and goodness.

Theologically Auden was well read, thoughtful and conservative. Those who developed theologically after the catastrophe of the World Wars of the 20th century tended to take a very definite line against what they regarded as the mish mash of alternative views that then prevailed. Certainly Auden's tone of voice was no less confident and authoritative when writing on theology than it was when he was writing on literature. When he returned to faith as an adult, he was influenced by Kierkegaard, the fountainhead of 20th century existentialism and by Reinhold Niebuhr, the most influential American theologian of the 20th century, with whom and his wife, he became good friends. They shared a strong sense of the propensity of human beings to deceive themselves and collude in illusions, particularly moral illusions. From this first stage of his theological reading he was reinforced both in his understanding of the dark side of human nature and the crucial importance of individual choice. He never lost his sense of the importance of the individual and individual choice. Names were crucially important for Auden because he believed that it was in the name that you became aware of the uniqueness of that individual. God, being God, was able to name every particle of the universe, and see its relation to every other.[26] Prayer for him was above all an act of attention to that unique individual, and one wonders about the influence of Simone Weil on him at this point.

However, what was interesting was the way he came to stress the importance of Christ not simply for the individual, but for the city, for organized human life in the city. This comes out in what is perhaps the most profoundly Christian set of poems he wrote, 'Horae Canonicae'[27], seven poems based on the seven monastic hours. But what they are concerned with is our life together as human beings, our life in the urban jungle. So from one point of view the poem is about an individual getting up and going about his day. But at the same time it is about the city in which Jesus is going to get killed in order to redeem the world.

'Prime' begins with a wonderful description of what it is to wake up in bed and then seems to include the whole world waking up to something sinister in the 'lying self-made city'. The hours continue with the same mixture of the personal and the universal, with all somehow rooted in a terrible event elsewhere.

For without a cement of blood (it must be human, it must be innocent)

No secular wall will safely stand.

The city is our essential organized life together, but what we hope for is something much more relaxed and carefree:

(And I shall know exactly what happened

Today between noon and three)

That we, too, may come to the picnic

With nothing to hide, join in the dance

As it moves in perichoresis,

Turns about the abiding tree.

Perichoresis is a technical term in theology referring to the way the different persons of the Holy Trinity dwell in one another, but here it seems to suggest that in the dance of humanity round the abiding tree, there is a mutual indwelling of the divine and the human.

This is a verse which sums up so much of Auden as a Christian and a poet. For him life is essentially life together, life with one another, social life; and this took its most essential form, at once sacramental and enjoyable, in the meals we share. But it is noticeable here that the meal is a picnic, an image that conveys the relaxed and carefree, and as conviviality in the fresh air brings together the city and the country. But there is nothing sentimental or escapist in Auden's view on how this wonderful end state is achieved. 'It depends on what happened between noon and three'. It is this breaking down of the barriers of our pride before the cross, that brings us before others 'With nothing to hide' and leads us to join in the dance of humanity. But this dance is at the same time the dance of God in humanity, for the perichoresis of the Blessed Trinity, comes, through Christ and the Holy Spirit, to be an indwelling of God in us. God and humanity are at one in that dance, a dance which turns about the tree, at once the tree of life and the cross as the definitive statement of Divine Love.

©The Rt Revd Lord Harries of Pentregarth, Gresham College, 15 January 2009

[1] W.H. Auden, 'Twelve Songs', IX, Collected Poems, ed. Edward Mendelson, Faber, 1976, p.120

[2] Arthur Kirsch, Auden and Christianity, Yale, 2005. The book is the result of a life-time's study of Auden and is both scholarly and judicious, with no religious axe to grind, either for or against.

[3] W.H.Auden: Prose Vol III, ed. Edward Mendelson, Faber, 2007, p.353

[4] (Contribution to Modern Canterbury Pilgrims) in W.H. Auden: Prose vol III, ed. Edward Mendelson, Faber 2008, p.574

[5] Auden came to dislike some of his earlier poetry and did not include this in his Collected Poems.

[6] Forewards and afterwards, selected by Edward Mendelson, Random House, 1973, p.69-70

[7] Interview with Roy Perrott, Observer Reivew, 28 June 1970

[8] ibid.

[9] Prose Vol III p.579

[10] According to Harold Norse, who was Auden's part-time secretary from 1939-1945 it was a 'marriage made in hell', and Auden was 'a complete door mat' emotionally. 'The Advocate' the national gay American journal.

[11]Edward Mendelson, 'Auden and God', in New York Review of Books, Dec 6 2007

[12] 'Precious Five', Collected Poems, p.447

[13] Collected Poems

[14] 'Epistle to a Godson', ibid.p.624

[15] 'In Praise of Limestone' ibid. p.414

[16] 'The Listener', 22 Dec 1937

[17] T.S. Eliot, 'Four Quartets', The Complete Poems and Plays of T.S. Eliot, Faber, 1969, p.180

[18] 'Tonight at Seven-thirty', Collected Poems, p.533. Olam comes from the Hebrew, and combines that which is hidden with a vast period of time, so perhaps everlasting.

[19] Prose, Vol III, p.589

[20] Prose Vol III, p. 203

[21] ibid.p.207

[22] 'The Truest Poetry is the Most Feigning', Collected Poems, p.470

[23] John Fuller W.H. Auden: A Commentary, Faber, 2007, p.453

[24] Emily Dickinson, The Complete Poems, ed.Thomas H. Johnson, Faber, 1970, p.506

[25] Collected Poems, p.624

[26] 'Elpithalamium', Collected Poems, p.571. See the last verse

[27] Collected Poems, p.475

This event was on Thu, 15 Jan 2009

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham College plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login