Once – so the story goes – everyone believed in God. Then along came science, freedom of thought and modern ideas, and people began to doubt. Now most people don't believe. Sooner or later, no one will. But this story isn’t true; and not just because the prophecy seems dubious. In reality, almost all of us answer the great questions of religion – do we believe, doubt or reject? – in ways that don’t really have much to do with ideas, science or philosophy. We take our stands, whatever they are, for more intimate and intuitive reasons, and then construct the philosophy we need to justify them. The history of both belief and unbelief is an emotional history before it is an intellectual one.

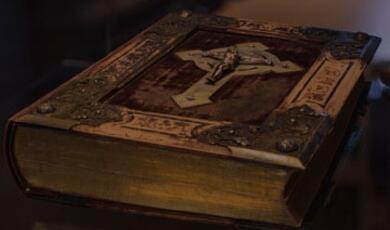

This lecture series by Professor Alec Ryrie will not re-tell the philosophical history of religious doubt from the Enlightenment onwards but will look back further, to the age when the newly-minted word ‘atheism’ became a cultural obsession: The Renaissance, the fifteenth, sixteenth and especially the seventeenth centuries. This was the age that wrote the emotional scripts of modern unbelief, scripts which we are still playing out today. It was a time when serious thinkers were all-but universally agreed on the reality of God. But still, people doubted.

The medieval world’s hidden but ever-present undercurrent of self-taught scepticism was joined in the 1500s, in the Reformation era, by new streams of doubt: paralysing uncertainty, agonised apostasy, liberating defiance and the bold pursuit of a hoped-for truer, deeper faith in places of old certainties that now rang hollow.

The lectures in this series will dwell on some of the giants of the age – from Machiavelli and Montaigne, through Raleigh, Marlowe and Shakespeare, to Thomas Hobbes, John Milton and Baruch Spinoza – but also on ordinary men and women who, whether with delight or with horror, found themselves doubting or denying what they had once held true.

Login

Login