The Art of Illustration: Millais, the Pre-Raphaelites and the Idyllic School

Share

- Details

- Text

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

The final and 'most indispensable' founding principle of the Pre-Raphaelites was: "to produce thoroughly good pictures and statues". Derided by the establishment (including Charles Dickens) for producing art which was ugly and backward, the work of John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Holman Hunt have since come to take its place as perhaps the most important point of British art in the 19th Century.

This lecture looks in particular at the illustrative art of these movements and artists.

Download Text

Dr Paul Goldman

18/10/2010

For a period of no more than twenty years, between about 1855 and 1875, there was a remarkable outpouring of fine black and white illustration in books and periodicals in Britain. It has frequently been termed a 'Golden Age', but preferable to such hyperbole, is a more reasoned evaluation of an era when the art of illustration was recognised by a number of distinguished artists as being as valuable and serious an occupation as painting in oils. Today I want to examine some of this activity and I will attempt to explain why it happened when it did, and also why it appeared as it did.

In order to put this phenomenon or indeed this explosion of extraordinary achievement into some sort of context, it is first necessary to display something of what went on before and how conditions altered so enabling it all to be made possible.

In addition, a few preliminary remarks are required on what sorts of illustrations were involved and how the designs made by the artists actually reached the readers. Finally, I will say a little about the decline and eventual demise of this kind of illustration after about 1875.

Although it was an age when it became increasingly feasible to illustrate works on history, topography, architecture, science and anatomy as well as a myriad of other essentially technical and factual subjects, I am concerned primarily with illustrations to literature.

Today the only type of imaginative writing which almost invariably attracts illustration is that of children's books and within that world it tends to be restricted to books intended for younger children rather than teenagers.

For example the Harry Potter books are not illustrated, although to contradict myself slightly, the novels of Philip Pullman regularly contain small vignette designs. However, in Victorian times poetry, religious and improving works, novels and serials aimed at adults, as well as other literary forms were also expected to be accompanied with images by an ever increasingly insatiable readership. Indeed it was common for books to be advertised emphasising both the text and the illustrations.

Although illustration was not in itself a novel phenomenon, it was during the 1860s that there emerged a definite shift in the relationship between the image and the text. One of the clearest hallmarks visible in the illustrations of this period was a growing equality, verging sometimes on domination, between the illustration and the literature. This situation came about largely because, at least for a time, so many of the artists saw the activity of designing for books as important, worthwhile and as intellectually demanding as painting in oils. They now saw that the narrative element in painting which so pre-occupied them could also be dealt with in a highly direct manner through illustration. The role of John Everett Millais in the movement as the leading Pre- Raphaelite illustrator was one which encouraged other artists to attain remarkable levels of achievement and intensity. Indeed his presence, I believe, actually assisted his fellow practitioners to produce more distinguished work than they otherwise might have done.

At this time also the technique of wood-engraving became the dominant medium in book and periodical illustration because it provided the enormous advantage over rival methods as it enabled image and text to be printed together in the same press and at the same moment.

Other ways of printing illustrations in books such as etching, steel-engraving or lithography almost invariably involved a separate printing of type and design. In other words, the image had to be printed and then bound into the publication when the letterpress had been prepared. Hence such ways of illustrating were much slower and more costly than wood-engraving. Wood-engraving itself became a highly organised, even an industrialised business, with numerous large London firms, notably those run by the Dalziel Brothers and Joseph Swain entirely taking charge of the work. In the case of the entrepreneurial Dalziels, they were almost invariably responsible for employing and paying the artists on behalf of the major publishers of illustrated material. Perhaps the best known and greatest of these was George Routledge. The Dalziels in particular saw their role, sometimes erroneously, as impeccable arbiters and indeed formers of public taste. However, despite their somewhat overblown belief in their own importance, it is certainly true that they employed highly skilled engravers, many of whom we now believe to have been women, at sweatshop wages, and since the work was regularly done at home and at speed overnight, costs were forced down still further.

Although the artists usually drew direct onto the boxwood blocks which were then cut by the engravers, the blocks themselves were generally used only for the purpose of taking proof or test impressions. These were then sent to the artists for checking, re-drawing and marking (known as 'touching', and once satisfied, electrotype facsimilies in metal were made of the wood blocks and it was these that were generally used in the printing process. Occasionally, in expensive gift books produced in small numbers, the woodblocks themselves would be printed from, but it was far more usual to store them in case of accident, breakage or cracking to the electrotype.

Hence if something untoward occurred, it was a relatively simple matter to produce a new electrotype derived from the original master block which had been approved by the artist.

It is also worth mentioning here, that Victorian publishers, being hard-headed businessmen, regularly re-used blocks time and time again and sometimes over many years in innumerable subsequent publications. They would routinely insert illustrations, which were in stock, if the new text lent itself naturally to this treatment, or, as was frequent, even if it did not. For example, it is not uncommon to discover noble designs originally made for some dramatic poem of love and loss, clumsily pushed in to accompany a wretched and utterly unrelated piece of verse, often decades after their initial appearance. Such cavalier activity means that it can sometimes be sometimes prove difficult to be certain if a particular engraving is being used on a first or a subsequent occasion. The situation is complicated still further by the irritating habit of re-titling the re-used images to enable them to fit in with the later texts involved.

The illustrative background of the 1820s and 1830s in Britain was one where two clear conventions at least can be identified. The first of these was personified by the refined world of the Annuals, and the second may be loosely termed the theatrical or comic tradition which was essentially a style of illustration largely derived from the single-sheet satire or cartoon.

The Annuals were in essence modest productions, small in format, aimed almost invariably at specific groups of readers, notably women and children. These delightful if neglected publications often sported attractive covers sometimes embossed in relief, or on occasion finished in such luxurious materials as watered silk.

Their themes were frequently religious and morally improving and such volumes were mainly edited by enthusiastic amateur authors. The literature, both poetry and prose, was a mixture of new and reprinted pieces, much of which was of little interest, yet the annuals also provided a place for some major writers to publish.

Among the distinguished poets who placed verse in these little books can be numbered Southey, John Clare, Coleridge and Wordsworth.

The illustrations were generally limited to no more than 12 per volume and they tended to be steel-engraved plates reproducing paintings shown first at the Royal Academy by popular contemporary artists such as Turner, John Martin, Thomas Lawrence and Richard Parkes Bonington. In some of the annuals, especially those for children or those with humorous content a few newly commissioned designs might be included which did not merely reproduce successful paintings in oils. The real point to make is that hardly ever did they relate in any very strict sense to the literature which they accompanied. Their role then was one that was essentially decorative, rather than in any meaningful way, genuinely illustrative.

Artistically the annuals had little effect on the illustrators of the Sixties and, by the late 1850s they were virtually extinct, presumably because the public now was demanding originality in illustration and not simply reproductions of paintings, however elegant and sophisticated they might have been as specimens of printmaking.

In complete contrast, the theatrical or comic tradition exerted a considerable influence on the later illustrators and it was a convention which went far beyond the mere selection of subject matter. It affected not only the style of draughtsmanship of numerous artists whose work was in no way comic in nature, but also had ramifications on how a design might appear on a page in relation to the letterpress.

This is often referred to as the mise en page. It was a tradition which developed out of the single- sheet satires made by artists such as Gillray, Rowlandson, George Cruikshank and Richard Newton and these were works which had attained their greatest heights of originality, sheer caustic rudeness and impudence between the 1770s and around 1830. This paved the way for some of the illustrators of the 1830s and 1840s, notably Robert Seymour, Hablot Knight Browne (PHIZ), W.M. Thackeray (an illustrator as well as a novelist) , John Leech and George Cruikshank himself.

Among the largely non-comic artists who worked in this style, at least at times, we might mention, J.C. Horsley, William Mulready, John Gilbert, William Harvey and even John Tenniel. Several artists would continue to produce illustrations during the 1850s and beyond who regularly remained loyal to this tradition.

The chief characteristics of this genre of illustration were a vignette-like nature, frequently playfully cursive line drawing, and a somewhat generalised approach to emotion which was reflected both in facial expression and in the poses of limbs and bodies. In addition, the images tended to be lightly printed and (at least to my eyes) appear subservient and essentially unequal to the text.

[SLIDE] My first example of this type of illustration is by William Mulready and it appears in an 1843 edition of Oliver Goldsmith's The Vicar of Wakefield. This is a significant publication since it is illustrated throughout by the one artist and the text is complemented by him with grace and sensitivity. He has also been very well served by his wood-engraver, John Thompson. Mulready's groupings in this book are invariably pleasing and harmonious, although as an interpreter he might today be considered a little bland.

[SLIDE] Here now is a design, made some five years later by John Tenniel for an edition of Aesop's Fables, entitled 'The Travellers and the Bear'. (1848) Here there are visible some clearly Germanic stylistic devices - the first is the sharpness of the outlines and the second is the manner in which the design appears to be creeping up the side of the page to almost encircle the letterpress. This feature of hard lines was derived via an admiration for members of the German Nazarene school of artists notably Schnorr von Carolsfeld, Moritz Retzsch and Friedrich Overbeck who flourished from about 1809 until the 1830s. The motif of placing text within such an illustrative framework looks back, however, far further to Albrecht Dürer's Prayer Book of the Emperor Maximilian, which had been republished using lithography by Rudolph Ackermann in London in 1817. This single event proved immensely influential on the artists of the 1840s and beyond. If Tenniel had not proved so apt and memorable an illustrator for Alice in Wonderland which was published in 1865, today we might know better his numerous other books illustrated with the panache revealed in this happy and facile example. Nevertheless, even inAlice he remains true to this Germanic influence especially in the sharpness and precision of his line. I now want to move forward a few years to a volume which appears to make a real breakthrough to a more modern style of illustration in a striking and highly dramatic manner.

3. [SLIDE] This book is The Music Master and a New Series of Day and Night Songs by the Irish poet, once extremely celebrated, William Allingham (1824-1889). It was published by the firm of George Routledge in a small octavo format and clad in a modest blue cloth binding in 1855. It contained wood-engraved illustrations by three of the leading Pre-Raphaelite artists, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Arthur Hughes. Millais and Rossetti provided a single design each, while the remaining seven were entrusted to Hughes.

Those by Hughes seem somewhat immature, archaic and almost unformed, looking back as it were, to the style of the 1840s especially in this drawing which is reminiscent of the fantasies of artists such as Richard Doyle and Richard Dadd.

[SLIDE] Although the Millais image is of interest I do not have a slide of it, and in any event it is completely outshone by Rossetti's extraordinary design for 'The Maids of Elfen-mere' which springs off the page in almost shocking contrast to the other illustrations in the book. Here, suddenly is a highly serious, intellectual and psychologically intense illustration with which the artist, by sheer force of personality and power of the image places himself on an equal footing with the text of the poem. Several Pre-Raphaelite devices are on display here - the dominant forms and more especially the almost monumental figure in the foreground, the contorted, twisted nature of the body, the real suggestion of emotional conflict in the features, and a recurring fascination with a 'remote past'. For the Pre-Raphaelites this meant a somewhat romantic and totally unrealistic view of life in mediaeval times.

An additional point to be made here is to stress that for these artists, at this particular point in their development, telling a story was central to their approach to artistic endeavour.

This single design was enormously influential, not just on Millais and the other Pre-Raphaelites, but also on numerous other artists who were involved in designing for books at this period. The young Edward Burne-Jones wrote of it, in admiration, in 1856 'It is I think the most beautiful drawing for an illustration I have ever seen, the weird faces of the maids of Elfinmere, the musical movement of the arms together as they sing, the face of the man, above all, are such as only a great artist could conceive.'

5. [SLIDE] In 1857 Edward Moxon published his celebrated illustrated edition of the poems of Tennyson, now known simply as the Moxon Tennyson.

In some ways this is an even more central book as regards a changing view of illustration than The Music Master, since it contains a disconcerting, even a somewhat staccato, amalgam of both the startlingly new and the older and more conventional styles. Leading exponents of the 1840s such as William Mulready, J.C. Horsely, Clarkson Stanfield and Daniel Maclise rub shoulders uncomfortably with the new young turks, notably Rossetti, Holman Hunt and Millais.

This is a design, made by Hunt for The Ballad of Oriana

'In the yew-wood black as night,

Oriana

Ere I rode into the fight

Oriana

While blissful tears blinded my sight

By star-shine and by moonlight,

Oriana

I to thee my troth did plight

Oriana'

This drawing, impeccably engraved by the Dalziel Brothers, reveals just how strongly the poetry of Tennyson appealed to the Pre-Raphaelite artists. It was a nebulous and utterly unrealistic view of the past, but it was also one which enabled them to revel in a world populated by gallant knights and tragic damsels - beautiful visions, remote and dreamy.

[SLIDE] It was also a situation which was full of appeal for Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who remarked that he liked the practice of illustration because, as he said, it enabled him free rein to 'allegorise on my own hook'. In other words, he could use the poem as a leaping-off point for him to indulge in unrestrained fantasy and imagination. This is one of the drawings he made for The Palace of Art and, dramatic and harmonious though the composition is, it is extremely difficult to ascertain exactly which passage is actually being depicted. Indeed, Tennyson himself had little time for illustration at all, and it seems that he never showed much interest in looking at the drawings before they were engraved. Apparently he gave up even attempting to discover how Rossetti's design related to his text but it seems most likely the passage which directly prompted his image is this one ...

'Or in a clear wall's city on the sea

Near gilded organ-pipes, her hair

Wound with white roses, slept St. Cecily ;

An angel looked at her.'

While it is problematic to discover exactly what Rossetti intends by the soldier munching an apple in the foreground, by the same token, it is clear that the angel is doing rather more than 'just looking'. This magnificent and contradictory drawing reveals that Rossetti, like many of the other Pre-Raphaelite artists was most suited to design only for poetry, and for a particular genre of verse at that.

[SLIDE] Millais, in contrast, hints in his contributions to the Moxon Tennyson at the two aspects which perhaps most fully characterise his work as an illustrator. The first of these is his prolific and industrious nature and the second is his variety both in style and in subject matter. He provides 18 designs here while there are 7 from Hunt and a mere 5 by Rossetti.

This is his illustration to A Dream of Fair Women and, although it may be compared in spirit with the drawings by Hunt and Rossetti we have already looked at, the essential point of departure offered by Millais is that he accurately and thoughtfully relates his image directly to the lines of the poem. It is, of course, Cleopatra.

'(With that she tore here robe apart, and half

The polish'd argent of her breast to sight

Laid bare. Thereto she pointed with a laugh,

Showing the aspick's bite)'

While this particular verse is printed in parentheses, Millais has seen in the words a genuinely dramatic moment which he feels is appropriate and logical for him to render visible. Far more than simply describing the lines in visual terms, he goes further by emphasising their significance in the narrative with a strength which I maintain illuminates their meaning and confers a potential for deeper perception. Stylistically too, this design is full of subtle gradations of tone which delicately complement the other-worldly gaze of the face. In certain respects the image is a simple one - a single and dominant figure with little apparent distraction. Its directness was to prove a device which Millais was to employ on numerous occasions during his career as an illustrator.

[SLIDE] This next illustration, which is from the same volume, reveals just how versatile Millais was in being able to tailor his image and his style to suit the words. The poem is Edward Gray and the design appears above the following lines ...

'sweet Emma Moreland of yonder town

Met me walking on yonder way.

...And have you lost your heart ?' she said ;

'And are you married yet, Edward Gray ?'

Sweet Emma Moreland spoke to me :

Bitterly weeping I turned away :

'sweet Emma Moreland, love no more

Can touch the heart of Edward Gray'.

The sparely drawn line which pares the scene down to its essentials immediately imbues the moment with a sense of brooding inner conflict, and this is a world away from the remote past redolent in so many of the other poems in the collection. Typically Millais is also entirely at home with contemporary costume - in less deft hands such an image might become mawkish or even plain dull. Instead we are led into the atmosphere of the verse swiftly and skilfully and this is assisted also by use of the bold method of placing the figures as if they are turning aside from the viewer.

[SLIDE] If so far we have looked at two distinct Millais styles - they might be termed 'Ancient' and 'Modern' then with this design, made to accompany St. Agnes' Eve, the artist proves that he is undaunted in tackling the mystic and the religious.

Deep on the convent-roof the snows

Are sparkling to the moon :

My breath to heaven like vapour goes :

May my soul follow soon !

This poem is a long way removed from Keats' celebrated and sensual striptease version and is indeed profound and affecting. Millais meets the challenge with a drawing of simple sincerity and once more he meticulously portrays the actual lines themselves.

The breath turning into vapour before our eyes in the chilly atmosphere is a remarkable achievement both as a concept and in the execution and the engraving by the Dalziel Brothers.

Millais is by far the most varied and the most consistent of all of the Pre-Raphaelite illustrators. Unlike most of the others he was not confined by his nature to poetry but was equally competent and confident in tackling prose of all kinds, children's books, contemporary or reprinted literature as well as books aimed at particular readerships such as women and girls.

He was an unique figure also in that he continued to make illustrations throughout his career as late as 1882, long after most of the other Pre-Raphaelite artists had abandoned the activity. Another important difference which should also be stressed is that he was almost invariably able to work to tight deadlines - an essential quality especially when engaged in making designs for magazines or part issues. Rossetti, Hunt and Ford Madox Brown tended to agonise over their illustrations at such lengths that this rendered them hopelessly uncommercial and hence unattractive both with the engravers and the publishers.

[SLIDE] This design by Millais appeared in 1858, a year after the MoxonTennyson in a book of poems selected by Charles Mackay entitled The Home affections pourtrayed by the Poets and it accompanies an anonymous Scottish ballad entitled The Border Widow and the relevant lines which should be read I believe in a Scottish accent, which I will not attempt read as follows ...

The man lives not I'll love again,

Since that my comely knight is slain ;

With one lock of his yellow hair,

I'll bind my heart for evermair

Although perhaps in mood the design suggests something of the themes explored in the Tennyson volume, Millais conveys here with real power the somewhat more rough-hewn nature of the verse.

The large central figures continue this favourite Pre-Raphaelite compositional device and achieve a telling contrast both with the scene of devastation in the background and the poignant discarded sword and helmet in the foreground.

[SLIDE] While looking at the next image, which is Millais's illustration to a poem by James Grahame called The Finding of Moses published also in 1858 in an anthology entitled Lays of the Holy Land, I think I should offer some hints as to why conditions during this period were conducive to so remarkable an output of imaginative illustration by innumerable outstanding artists.

Certain significant changes took place which I divide under three main headings. These are, respectively, social/educational, economic and finally, technical/mechanical.

In the area of society and education, the foundation of the Sunday School Movement by Robert Raikes in 1780 which was followed some 19 years later by Hannah More's Religious Tract Society led to a larger public being able to read than ever before.

This, in turn, and over time created a demand for literature of a religious or improving nature much of which was illustrated, since both these august bodies recognised early on the didactic value of visual images to reinforce their Christian message. It was the RTS and another hugely influential organisation, the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK) which not only published much of the reading matter but also distributed more of a similar nature emanating from the purely commercial publishers.

In order to give an example of just how massive the scale of operations was at the period we are concerned with, in 1861 the RTS was distributing some 20 million items of literature as well as 13 million copies of periodicals.

Among the latter were titles such as Sunday at Home, The Leisure Hour, and Churchman's Family Magazine all three of which carried designs by the leading artists. For example, in 1866 Simeon Solomon produced a celebrated series devoted to Jewish Customs for The Leisure Hour, while practitioners of the calibre of Thomas Morten, Matthew James Lawless, Henry Hugh Armstead and Millais himself all made notable contributions toChurchman's Family Magazine in 1863.

In parallel with such significant developments in religious publishing came a greater emphasis on reading skills which were hammered into children by rote and strenuously encouraged by the state. Payment by Resultswhich was a Victorian forerunner of the National Curriculum and which has a familiar ring to it, ensured, albeit painfully, that more children than ever before gained at least the rudiments of reading. The scheme meant that every failure per pupil per subject, lost the school 2 shillings and 8 pence from the following year's grant. A consequence of such draconian methods ensured that the pool of those who could benefit from the joint attentions of publishers and distributors was significantly enlarged.

However, it is also worth saying in addition that this increase in publishing activity, both illustrated and unillustrated, could only have come about as a result of several significant changes in economic conditions.

On the 1st of July 1855 the compulsory newspaper stamp duty was removed and, six years later the duty on paper itself was similarly abolished.

These two events, coupled with the introduction of esparto, a North African grass into papermaking as a cheap alternative to rags, helped create an environment in which books and especially periodicals could flourish.

A few further statistics will serve to illuminate the point - The Newspaper Press Directory of 1865 lists 1271 newspapers and 554 periodicals as being in publication in the UK, and between 1830 and 1880 between 100 and 170 new titles began publishing during each decade. Nevertheless, as with all such facts care should be taken and large numbers of these organs perished early in their lives.

There were also other developments which contributed still further to a propitious publishing environment and the first of these concerned the very practice of bookselling itself. In 1852, the highly protectionist Booksellers' Association, which had always endeavoured to keep the prices of book at an artificially high level, was dissolved. This came about following a lengthy and bitter public debate on pricing which had involved such eminent figures as William Longman, John Murray and Gladstone. As a direct result of this single event, the retail prices of books fell rapidly, and now most buyers expected, and indeed almost invariably obtained a discount of 2d or 3d in the shilling on the price of books.

At the same time the incomes of the middle-classes rose and it was this very group which was, in reality, the most likely to be able to afford illustrated material, which was now being made conveniently available at an even lower cost than before.

If the social ,educational and economic conditions were now such as to permit a greater volume of illustrated material to be produced, there still remained technical and mechanical difficulties to be overcome in order for this explosion in illustrative activity to be fully realised.

Three improvements in the technology of printing were crucial. The first was the decline in the use of the hand-press and its replacement by the more powerful and far quicker platen and cylinder presses. By the mid 1860s only work of the most luxurious nature was done on the hand-press and indeed it is now generally believed that the last time a hand-press was used for a trade book was in 1864. The printer was the celebrated Edmund Evans and the volume concerned was entitled A Chronicle of England. The second innovation was the discovery in 1839 and subsequent patenting of the revolutionary process of electrotyping by Thomas Spencer and others. This enabled facsimile reproductions of wood blocks to be produced in metal hence enabling illustrations to be printed from them while preserving the original blocks without fear of cracking or damaging them. As I remarked earlier these blocks were used chiefly for proofing. The artist would make corrections based on proofs taken from the wood . When he or she was satisfied an electrotype would be made from it leaving the wooden block as a master. Should then the metal plate be damaged it would be a simple matter to produce a further facsimile based exactly on the original which had the artist's approval. The swift rise in the use of photography enabled designs to be transferred to blocks by 1856 (rather earlier than was originally thought) and this permitted the preservation of the original drawings. Hence the artist could sell the original design and also receive payment from the publisher or the engraver and so in effect was able to market his wares twice.

Before returning to the images I want to make one further point about technical advance and this is to stress the importance of the virtual completion of the rail network which was accomplished during the 1850s.

Carriage charges were low and the geographically comprehensive nature of the system, coupled with a vast improvement in the provision of postal services ensured that books ordered from booksellers or publishers could be easily obtained almost anywhere in the country. However, I think it extremely unlikely that most of the illustrated books of the kind I am concerned with would have been available for purchase at W.H. Smith's station bookstalls which came to prominence at the same time as the railways themselves. More certainly though it seems that illustrated magazines such as issues of the Cornhill and Good Words would have been offered to passengers at these ubiquitous outlets.

[SLIDE] I am showing now Burne-Jones's very first illustrations which were made for his friend Archibald Maclaren's children's book The Fairy Family. This appeared also in 1857, the same year as the Moxon Tennyson but rather tellingly both the story and the designs were published anonymously. The drawing is unsure, even gauche and it owes something to those masters of whimsy and fantasy such as Richard Doyle and Richard Dadd who I mentioned a little earlier. It is worth noting here that the artist always felt embarrassed by these immature though charming images and never acknowledged that they were his work, even when the book was reprinted in 1874.

[SLIDE] In 1862 Dante Gabriel Rossetti made two designs for his sister Christina's eerie and disturbing poem Goblin Market. These energetic and accomplished works are significant because they are fully equal in power and intensity to the text of the great poem itself. Richly printed and brimming with confidence they were followed in 1866 by two further drawings, this time for Christina's The Prince's Progress. It is difficult to overestimate the significance of these two books for they are important not just on account of their outstanding artistic and literary content.

[SLIDE] Unlike so much of the illustrated literature of the time which was largely reprinted, the two are genuine first editions. This is the frontispiece and title-page of The Prince's Progress. In addition, both works are far closer to what contemporary readers would understand asmodern books, since they succeed as complete artistic creations. By this I mean that Dante Gabriel was responsible not just for the illustrations but for all other aspects of the design, even down to details such as the colour of the binding material and the endpapers and paste-downs.

[SLIDE] This is the cover of decorated cloth cover of The Prince's Progress again bearing a design by Rossetti himself. It is difficult to believe that so striking, chaste and bold a conception is 150 years old.

These two books are, however, uncharacteristic, in an era when most commercial publishers would only trouble to commission illustrators when a book had already won its financial spurs in the market place, without illustrations.

[SLIDE] As one example, here is Millais's The Good Samaritan for The Parables of Our Lord (1864).

This was a text which had certainly been in the public domain for an extremely long period before Millais provided some of his very greatest and most profound designs to accompany it. In all he made 20 drawings over a period of 6 years and the first 12 appeared in the periodical Good Words in 1863, a year in advance of the publication of all the images in book form.

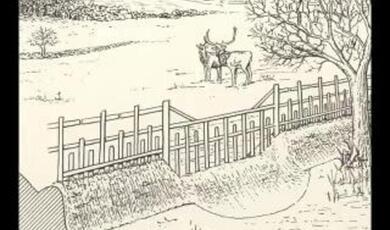

[SLIDE] This is The Prodigal Son from the same cycle. It was in 1864 that all the drawings were published in a handsome and now rare volume where they received the benefit of more fastidious printing, presumably from the original wood- blocks, and on better paper than in the magazine issue.

By placing the Bible story in his familiar glens of Perthshire, Millais sensitively yet potently enlarges the Christian message.

While Millais is arguably the most varied, consistent, accomplished and prolific of all the illustrators under discussion, there are numerous others who warrant examination.

[SLIDE] Arthur Hughes is perhaps best known today for paintings such asApril

Love (Tate Britain) but he was also distinguished especially as an illustrator for children. He was the first illustrator of At the Back of the North Wind by George Macdonald when the story was serialised in the periodical Good Words for the Young between 1868 and 1870.

Here, however, are two of his designs for Tennyson's Enoch Arden which was published in 1866, a mere two years after the initial appearance of the poem. It is significant because it may be counted among the very few illustrated books made by Hughes for adults and it is, in my view, a very successful and unusual example of a great illustrator fully complementing and enhancing a major work of literature. In this instance the text is contemporary with the design - Tennyson was, after all, very much alive when this particular edition of his poem was published.

[SLIDE] However, in contrast, when Holman Hunt produced The Morning Song

of Praise in 1867, the author was long dead. The book in question isDivine and Moral Songs by the Revd Isaac Watts which had been published first in 1715. It proved an immensely durable work and was much reprinted even up to the early 20th century and the succeeding editions were frequently illustrated. Some of you may even recall some of his verse, notably perhaps the opening of song xx

How doth the little busy bee

Improve each shining hour

And gather Honey all the day

From every opening Flower !

Millais was a prolific illustrator but the other Pre-Raphaelites soon turned away from the practice, often unable or unwilling to meet deadlines set by publishers and editors and preferring in any event the richer rewards both financially and in terms of status offered by painting in oils.

[SLIDE] As their contributions declined so another group of artists, more dedicated specifically to illustration as means of earning a living, came to prominence.

They have become known, not really very accurately, as the 'Idyllic School', chiefly because their subjects, sometimes idealised, occasionally verging on the sentimental, regularly were devoted to depicting poor people in rustic surroundings leading honest Christian lives. Unlike the Pre-Raphaelites they frequently concentrated their efforts on an unrealistic present as opposed to an unrealistic past.

However, there were other differences between the two groups. The Idyllists were essentially professional illustrators and few held genuine pretensions to making notable careers as painters in oils.

Several of them have faded into obscurity, not least perhaps because their work is often scattered in obscure volumes or long forgotten and neglected periodicals. One such artist is Robert Barnes and on the screen is his The Sick Child from what I would argue is his finest book entitledPictures of English Life which was published in 1865.

[SLIDE] Barnes and occasionally Frederick Walker may sometimes be accused of excessive sentimentality. This is Walker's Broken Victualswhich was published in an anthology or gift book called A Round of Daysin 1866. Nevertheless, it must be remembered that sentimentality in Victorian times did not carry with it all the negative connotations that it does today. The importance of childhood and its frequent depiction by artists should serve to remind us just how brief so many lives really were at this time, and the very high rates of infant mortality must, I believe, exert some influence on such illustrations of literature. Indeed, as we have just seen, Barnes's drawing is actually called The Sick Child - it was a scene far from idyllic and it was one that would be all too real and ever- present to most of the population. People would view juvenile illness, not as a temporary interruption to health but as a possible even a probable precursor of death.

22. [SLIDE] Walker was an immensely popular illustrator, much admired by his contemporaries, but of the Idyllic School artists, the most varied and gifted was perhaps Arthur Boyd Houghton. Both the examples of his work which I am showing were published in 1865. The first is Queen Labe unveiling before King Beder and it appeared in Dalziels's Arabian Nights' Entertainments The text at this point reads 'King Beder forgot insensibly that the Queen was a magician, and looked upon her only as the most beautiful woman in the world.' Houghton illustrated this enormous work almost single-handed and in a style in which he had almost no peer.

Millais made a few contributions to the same volume but Houghton was, on the whole, the master when it came to an exotic, Orientalist manner. Indeed of the members of the Idyllic School it is Houghton who may be most fairly be compared to Millais. Like him he could draw in a number of styles and was as comfortable drawing for prose as for poetry.

[SLIDE] While Millais outclassed him when drawing specifically for children,Houghton in his depicting them for adult readers achieved work of the highest intensity. This is Noah's Ark which appeared in another anthology or gift book entitled Home Thoughts and Home Scenes which once more was published in 1865. The verse was by leading women writers including Dora Greenwell and Jean Ingelow and all the 35 images were entrusted to Houghton. The somewhat anodyne title belies the actual appearance of these frankly extraordinary and disconcerting designs, which one modern commentator has labelled 'psychotic'. They are, in truth, some of the most disturbing images of childhood not only in the Victorian period but, I would argue, in the entire history of book illustration.

24 [SLIDE] Of all the artists in this loose grouping it is probably George John Pinwell who best exemplifies the term 'Idyllic'. Here is his The Island Bee, which was published in a gift book of 1867 entitled Wayside Posies. In this tender image of a child being comforted by her mother, Pinwell has produced a work of touching sincerity and directness. Pinwells's drawings are remarkable in that they actually tend to improve when cut on the block and he was an expert who knew exactly how best to draw with the engraver in mind. It was a skill which few of the Pre-Raphaelite artists, again with the notable exception of Millais, ever took the trouble to master.

25 [SLIDE] As I mentioned a little earlier, the illustrated magazines are an invaluable source of fine designs. Indeed for an artist such as Frederick Sandys, who may be placed with the Pre-Raphaelites, they are essential, since almost all his few drawings are scattered in their pages. This is Until her death from Good Words of 1862 and it typifies the various heady elements in his work which sometimes mix death and sexuality in mediaeval settings. There is also here a direct visual quotation from Albrecht Dürer's engraving of 1514, Melencolia.

26 [SLIDE] Millais too drew extensively for the periodicals. He illustrated Trollope's Framley Parsonage in the Cornhill Magazine during 1861 and 1862 and this shows Lucy Robarts, who is surely one of this author's most winning heroines. Several further Trollope novels were serialised in the magazines and Millais illustrated The Small House at Allington again in theCornhill from 1862-4 and later, in 1869 Phineas Finn the Irish Member in the short lived Saint Paul's , of which Trollope himself was briefly the editor.

27 [SLIDE] Millais continued to provide illustrations until 1882 but this is one from 1879 to W.M. Thackeray's The Memoirs of Barry Lyndon. It is my final slide and to conclude I should like to offer you a few thoughts as to why this genre of black and white illustration faltered in the mid 1870s and was virtually extinct by 1880. Mortality, photography, economics and a shift in public taste all had a part to play in its demise.

In 1875 three of the leading Idyllic School illustrators, Houghton, Walker and Pinwell died and these were tragedies from which the movement could not recover. However, the seeds of the destruction of trade illustration had been sown at the end of the 1860s, not least by the very success and popularity of the artists themselves. As they became established figures so the prices they could demand for their drawings rose sharply. As an example, in 1862 Charles Keene, primarily but not exclusively a comic illustrator notably in Punch, received 4 guineas a design but by 1868 he was able to demand 12. One inevitable result was that the number of illustrations in each magazine issue began to drop and falling circulations led to business failures and bankruptcies especially among the publishers, proprietors and, most notably the firms of engravers.

Photography which had been seen perhaps in its earliest years as a gentle household pet and since 1856 been routinely employed for transferring drawings onto the wooden blocks, now began to grow from a puppy into a mastiff. The great engraving shops of the Dalziel Brothers and Joseph Swain lost their dominance in the industry as photography itself came to be employed instead of the far more labour-intensive process of wood-engraving. The line-block, half-tone and the process block began to take over in the early 1880s and few of the 1860s artists, who relied for their effects on clean line draughtsmanship could adapt successfully to new opportunities which could now render with ease, tone, wash and texture. Finally a new climate in public taste meant that the books and the magazines of the type I have been discussing began to look plain out-of-date and seriously old fashioned.

Magazines of documentary reality notably the Graphic and the Illustrated London News grew in popularity and readership. Inexorably the illustrated books and periodicals of the 1860s were as doomed as the dodo.

Millais and a host of other artists made the 'Art of Illustration' for a relatively brief period central in British art, and I have only been able to show you a handful of them today. I would like to end by stressing once more the outstanding contribution to this field made by Millais and to quote what Forrest Reid, a distinguished and pioneering critic of the subject wrote in 1928 of the design which is now on the screen.

It depicts the final and heart-breaking decay of that philanderer Barry Lyndon and Reid perceptively remarks - 'The Last Days' is a masterpiece. The drawing of that drunken figure seated at the table is the most realistic and the most terrible design Millais ever made.'

© Dr Paul Goldman, Gresham College 2010

This event was on Mon, 18 Oct 2010

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham College plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login