Beethoven - Quartet No 9 in C major, Op 59 (Rasumovsky)

Share

- Details

- Text

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

One of six lectures devoted to a major work in the string repertory. Each will end with a complete live performance of the work by the Badke Quartet. The lectures will discuss both the historical and musical background of the work in question, and examine any particular performance problems that it raises.

The Badke Quartet, formed in 2002, is widely recognised as one of Britain's finest young string quartets. Recipients of the Leverhulme Junior Chamber Music Fellowship at the Royal College of Music from 2003-2005, and the Bulldog Scholarship for String Quartet at Trinity College of Music in 2006, the Badke Quartet has received widespread acclaim for its energetic and vibrant performances.

Download Text

Professor Roger Parker

I'll start today with an apology and a confession.

The apology (which can be brief) is that, in the initial publicity for this series, the quartet today was announced as Beethoven's Op. 95; but some time ago, and for eminently practical reasons, the Badke quartet and I decided to change to the same composer's Op. 59, no. 3. I sincerely hope this inconveniences no-one, and may even please a few of you.

The confession (which must be longer) is that I've been having a recurring nightmare about delivering this lecture series. The nightmares of people who appear before the public can be many and various: musicians, for example, have a number of classic ones. In mine, though, it's something quite particular. I arrive at Gresham College in good time for my lecture, armed with a talk crammed full of what dignity and scholarship I can muster. But as I come in, I glance at the notice board and see to my horror that I've got the programme mixed up: the quartet about which I've written my talk is actually due to be played next month; I've prepared the wrong work. What's to be done? The Badke Quartet have no time (and frankly, no inclination) to dash home and grab next month's music; and why should they? I decide I have two choices, neither of them pleasant. The first is to admit the mistake, perhaps making some flimsy joke about our postmodern condition and the arbitrary nature of the speech act, and then force myself to drone through half an hour of purgatory: an elaborate introduction to what everyone knows is a non-existent object. The other choice, which I favour, is to brazen it out: to talk about my quartet, then let the Badke play their quartet, and pray to Heaven no-one notices. If I'm publicly exposed at the end (which I surely will be), then I can always use that last refuge of the desperate teacher and say: 'Well, I'm glad someone was paying attention'.

I'm just about to enter this room, nervously shuffling my papers, when, mercifully, I wake up.

Is there a dark secret lurking within this simple story? I have to confess to being a very sceptical Freudian on most occasions, but the interesting thing about this nightmare is indeed what might lie hidden beneath its bizarre narrative. [pause] Unfortunately, though, I see that time is pressing on, and so will leave any Freudian explanations (deeply revealing and perhaps even shaming) to your collective imaginations.

***

Today, then, it's the turn of Beethoven: a chance to hear one of his greatest works: the third of the so-called 'Razumovsky' quartets, Op. 59. As I've said more than once in this series, the idea of the string quartet, its unprecedented prestige in the Western canon, is inescapably associated with Beethoven, who dedicated himself to the medium with peculiar intensity at three separate periods of his life, and who in the process created a body of work that all subsequent composers felt (some more willingly than others) they were obliged to emulate. The Beethoven quartets have long been regarded, by listeners and players alike, as the pinnacle of the repertoire: never to be essayed or talked about without a generous dose of that throaty awe we reserve for the weightiest monuments of our culture. I know you believe me, but test it out anyway. Type 'Beethoven string quartet sublime' into that little box on the first page of Google and you'll find countless reiterations of the same basic idea: Beethoven's quartets are transcendent; they hover over us, out there in the ether; they are forever relevant, beyond history.

What's striking is how far back this reverential attitude goes. Of course, there are famous stories of the incomprehension some of Beethoven's early audiences felt; but, remarkably and quite unusually for the period, the lack of understanding was very often assumed to be the fault of the audience rather than the piece in question. A good example is an early review of the Op. 59 quartets, which admitted that they were 'long and difficult' but followed this by saying that 'admirers hope that they will soon be engraved'. The message is plain: these works are complicated for areason; they are not entertainment; we need to study them in order to understand them. This attitude, which was common to most of Beethoven's instrumental works, gradually spread through Europe in the early decades of the nineteenth century, and was fuelled rather than dampened by the composer's death in 1827, an event that set in motion a huge wave of monument building and other types of memorialisation. In short, Beethoven's most famous works were powerfully implicated in enormous changes in the ways music was performed, listened to and written about. Let me list a few of these changes: the decisive emergence of silent, attentive listening; the parallel emergence of instrumental music as more serious than vocal music; an increasing sense that a certain strand of this instrumental music, now commonly called 'classical music', was spiritually uplifting and morally superior; a new hierarchy between the composer and the performer, one that saw the latter as merely a vehicle to express the thoughts of the former; an increased attention to, and reverence for, the score as a repository of the 'work'; and so on and on. Does all this sound familiar? It should do, because it marks the decisive emergence of 'our' classical musical world, with its concert going, its silent listening, and all the rest; a world that probably saw its peak in the state-sponsored 1950s and 1960s, and that is now, most would admit, in slow decline.

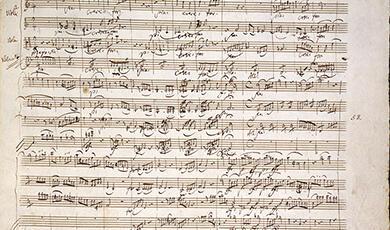

Like most iconic cultural figures, Beethoven's life story was powerfully inscribed onto his artistic production, in his case through application of the classic trope of 'three periods' (youth, maturity, and old age). This was something applied to Beethoven very soon after his death, and has retained a robust currency to this day. As I mentioned a moment ago, it happens to suit his quartet production very well, as there are substantial contributions in all three periods. First, around 1798-1800, come his youthful quartets, the set of six which make up Op. 18. These bear very obvious debts to Mozart's quartets, two of which Beethoven copied out in his own hand (a common mode of musical learning that we have almost entirely lost these days). Less obvious, but equally telling, is the debt to Haydn, who was still alive and indeed still producing quartets, with whom Beethoven had studied briefly in the early 1790s (when he first arrived in Vienna), and about whom he evidently felt no small degree of competitive anxiety. But these Op. 18 quartets, though broadly speaking they still retain the intimacy and 'conversational' character of Mozart and Haydn (the sense of being written as much for the performers as for listeners) also display an intensity that both Mozart and Haydn would probably have found disturbing. The first movement of Op. 18, no. 1, for example, is ferociously single-minded in its thematic economy, hardly a bar going by without some statement of its opening, 'motto' theme: so ferocious, in fact, that Beethoven later revised the movement, taking out a lot of this 'thematic working', this thematische Arbeit, and thus, according to some, disconcertingly 'de-unifying' his musical language.

Beethoven's middle period, sometimes called his 'heroic' period, began with a huge spiritual crisis around 1801: he realized, or finally admitted to himself and close friends, that he was going deaf, a disability that was disastrous professionally (much of his living was earned as a pianist), but that also - and in the end just as significantly - caused him to withdraw from social life. His emergence from this crisis was, in this sense paradoxically, by means of a compositional turn outwards: to a series of grand 'public' works that would cement his reputation as Europe's most celebrated composer of instrumental music: the Erocia symphony, the 'Waldstein' and 'Appassionata' piano sonatas all come from this period; and so too do the three quartets Op. 59 - which were written around 1805-6 and, as we shall see, partake freely of the spirit of these grandiose companions. Two further quartets, the Op. 74 and Op. 95 are also usually attached to this 'middle' period (they were composed in 1809 and 1810), although by that time Beethoven's 'heroic' phase was coming to a close.

After 1812 there came an important hiatus in Beethoven's composing life; a period of several years in which he produced very little, surrounded as he was by new personal crises and also - though we know less about it - by a sense that more modern musical fashions might overtake him. But then the last decade of his life saw the emergence of a radically new musical language, that of the so-called 'late style', which is characterized by great contrasts and extreme individuality. Near the end of this period, and thus near the end of Beethoven's life, there again appear a series of string quartets, the five so-called 'late quartets', some of which he seems to have written without obvious stimulus from commissions and which have seemed, to almost everyone since, a deeply individual summing-up of his entire career.

***

Let's turn back to the Op. 59 quartets, written as I said around 1805-6, when Beethoven, aged 35, was at the height of his productivity. They are called the 'Razumovsky' quartets because they were commissioned by a Russian count of that name, who was the Tzar's ambassador in Vienna, a keen amateur violinist and (not always the same thing) a confirmed music lover. One contemporary described Razumovsky as 'an enemy of the Revolution [presumably the French one] and a friend of the fair sex'; a description that sounds not entirely without malice. Equally important, though, in the creation of Op. 59 was a Viennese violin virtuoso called Ignaz Schuppanzigh, who was first violin in various quartet groups that were centrally involved in a great many of Beethoven's works for the medium. Schuppanzigh is crucial at this stage because, around the time that Beethoven was writing his Op. 59, the violinist formed a quartet that was set up specifically with a view to giving public performances. Such public quartet concerts had, it is true, been part of the London scene for some years (Haydn's Opp. 71 and 74 quartets were written for public occasions); but they were apparently a novelty in Vienna. What is clear is that Beethoven embraced this larger stage, this new quartet audience, with an enthusiasm that couldn't be improved upon. Although the Op. 59 quartets indeed retain some of the 'conversational' atmosphere of his earlier works, they also bear many traces of the symphonic grandeur and breadth that was so much part of Beethoven's music during this period.

As it happens, the opening of Op. 59. No 3 offers an excellent example of this strange mixture of the intimate and the grandiose; a mixture that is often woven into the very fabric of the musical argument. The quartet, which is in C major, opens with three radically contrasting musical ideas. First comes a slow introduction that is forbiddingly interior: it is densely chromatic and mysterious, and obviously modelled on the introduction to Mozart's C major quartet K. 465, a work that loyal audience members here will remember as the subject of the first of this series. It self-consciously explores a large and unpredictable space, both tonally and in terms of the quartet's range, the main connecting link being the cello, which gradually descends through its range as the chords progress. Second comes a very strange passage in which tonally ambiguous cadences from all four instruments introduce an improvisatory first violin, playing a solo line that seems like a wordless recitative, albeit with an obsessively repeated melodic and rhythmic idea. And then, third, comes an explosion of the home key, C major, expressed in a frankly orchestral manner; double stops and violin doublings articulating a banal little four-note figure. Let's hear those opening three ideas, in this and in my other except played by the Tokyo String Quartet:

PLAY CD TRACK 1: START TO 2:00

This is, as I said, an unconventional enough beginning. Even those well-used to sonata forms would have been hard-pressed to identify what exactly was going on. The first section is obviously introductory. But is that rhapsodic violin solo the start of the first movement proper, or merely another introduction? Certainly in tonal terms the real starting point seems to be that triumphant assertion of C major in the third section; but that in turn lacks the kind of motivic definition one would expect. What's more surprising, though, is that the rest of this long movement does little to clarify these perplexities, let alone suggests any hierarchical order in the themes. What we get instead is a constant alternation of the second and third ideas: a kind of dialogue between the 'private' and the 'public'; between, if you want, different views of what a string quartet might be.

The second movement takes us into equally unconventional territory, but of a very different kind. One of Beethoven's gestures towards his commissioner, Count Rasumovsky, was to feature 'Russian themes' in the final movements of Opp. 59, nos 1 and 2 (the one in no. 2 was used by Musorgsky in his opera Boris Gudunov nearly seventy years later); but in the third quartet he tried something altogether more radical, and that is an entire Russian movement. The 'exotic' flavour of this melancholy Andante is easy enough to hear: in the augmented second intervals of the opening violin melody; in the frequent pizzicato accompaniment of the cello (as if in imitation of a 'folk' instrument such as guitar of harp); and especially in the long passages of static harmony. Indeed, so successful is Beethoven in conjuring up this sense of geographical distance that the movement sounds to us uncannily like a 'nationalist' inspiration from decades later, by Dvorak or Borodin or Chaikovsky; only the extreme modulations and patient logic of the tonal return betray it back to its time and composer.

The third movement gestures in the opposite direction. Beethoven had during his 'middle' period tended to avoid the Minuet and Trio format, perhaps thinking it too redolent of eighteenth-century civility and preferring the more robust Scherzo; but here he returns to the now somewhat-old-fashioned form, in a movement that might almost be a celebration of Mozartian 'conversation', with a characteristic rhythmic motive in the opening seamlessly exchanged between instruments. As if to complete the 'antique' mode, the Trio's uncomplicated dance character and rising arpeggios even throw us back to the world of early Haydn and those 'divertimenti' that started the string quartet medium on its way. Only a typically Beethovenian harmonic jolt (you can't miss it) reminds us of the distance we have travelled.

Everything in this quartet has been a surprise so far, and the last movement is no exception. It is led into seamlessly, by a gentle coda to the third movement that ends on a question mark. But then, of all things, we are presented with the start of a formal fugue, led off by the viola at a furious tempo. Again we have a sense of dichotomy between the new and the old, the public and the private. Fugues were by now an ancient, learned device; but Beethoven casts this one in the most extrovert and 'public' of moods - as a display of evident virtuosity for the four soloists. What is more, as soon as the four entries have been completed he forgets all about formal counterpoint (though not about the subject itself) and explores instead the grandiose, 'symphonic' modes we remember from the first movement, especially that flamboyant celebration of an enormous C-major space on all four instruments. To prepare you for the onslaught, let's hear the opening of that last movement:

PLAY CD TRACK 4: START TO 1:13

This is, as you can hear, not for the fainthearted; and emphatically not for the willing amateur. Count Rasumovsky the part-time violinist may have paid handsomely for these quartets, and he even had the cheek to ask Beethoven for a few composition lessons (request denied); but it's difficult to imagine him reaching for his instrument when he saw what Op. 59 called for. This is emphatically professionals' music, with the first violin's part no less demanding than a concerto; the second violin (as always) constrained to dive manically between this mode and that of an accompanist; the viola as exposed and taxing as any in the repertoire; and a cello part that has made even the surest technicians blench at the way they are obliged to rattle up and down their huge fingerboard, imitating the scampering upper strings.

But for all that tension and strain - indeed, adding to it so far as the performers are concerned - this is (I should have said it before) one of Beethoven's most extrovert, even boisterous string quartets. It looks back with complex affection at older styles and manners, while also pressing ahead on an extraordinary musical journey. Here to play it for us, as always, is the Badke Quartet. Please join me in welcoming them.

Badke Quartet plays Beethoven, Quartet in C major, Op. 59, no. 3

Professor Roger Parker, Gresham College, 6 May 2008

Part of:

This event was on Tue, 06 May 2008

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham College plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login