The History of Street Performance: ‘Music by handle’ and the Silencing of Street Musicians in the Metropolis

Share

- Details

- Text

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

A discussion of the history of busking and street music in the City of London. Drawing on a range of historic sources – including selections from Henry Mayhew's London Labour and the London Poor and Charles Babbage's Passages in the Life of a Philosopher – particular focus will be given to the way in which various residents of the City responded to the ‘street music problem’ of Victorian London. This is by far the most heavily documented period in the history of busking and street music in the City. The street music ‘problem’ emerged in light of the growing middle and literary classes and the disruption the presence such street musicians caused to the quiet tenor of their home-working lives.

The debates that occurred here – which involved notable figures such as Charles Dickens, Charles Leech, and Charles Babbage – resulted in the development of the Street Music Act of 1864 and paved the way for much of the subsequent legislative control of street musicians in the City. The debates about street performances in London in this period shed light on the present-day situation of busking and street music in the City.

Download Text

09 July 2015

The History of Street Performance:

‘Music by Handle’ and the Silencing of Street Musicians in the Metropolis

Dr Paul Simpson

I should start by noting that talking about the history of street music poses some challenges. Street musicians are a near ubiquitous feature of the everyday life of many urban environments. As Cohen and Greenwood suggest in their History of Street Entertainment, this has been the case for centuries. However, while the name by which they have been known has changed, as has the specific nature of their acts and their means of gaining an income, a common circumstance for such performers is that they have maintained variously uncertain situations within those societies and those spaces.

Some of these performers have found themselves in a relatively privileged position. Historically, for example, a minstrel or player in the twelfth or thirteenth century may have been in receipt of the patronage of a ‘great man’ and so benefited from associated protections when travelling (either with such a patron, or separately). Without such patronage it would have been quite hard to move freely or spend any time in one place without being treated as an outlaw. Also, it would be quite common during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in England for itinerant musicians and other performers to be engaged by local authorities to play at certain civic events, giving them some associated standing.[i] And, more recently, we can think of those performers who are in receipt of a formal permit and licence from a local authority or landowner that afford them certain (albeit restricted) rights to perform. Covent Garden[ii] and the London Underground are perhaps two of the best-known contemporary examples of this in the UK.

These recognitions and accommodations noted, though, many other street musicians have found themselves in less enviable positions; itinerant performers were and are still very often viewed suspiciously by the authorities, and society as a whole, for their very mobility. Being perpetually on the move can mean that these individuals do not obviously fit within common social structures based around belonging and boundaries. For example, as Tim Cresswell notes, during the Middle Ages “Minstrels…were thought of as lecherous and irresponsible fly-by-nights”.[iii] Further, associations between such performers and beggars or vagrancy recur through this history of street music. Where the act’s quality did not meet an individual’s taste, a common response has been to dismiss a performer as ‘basically a beggar’ or ‘little more than a vagrant’. The presence of the patronage or other formal recognition just mentioned exacerbates this issue for what we might consider to be ‘freelance’ performers. In the past, these freelancers may have been hounded out of town or their activities repressed by the church. Today we have Statutory Nuisance Legislation and ‘Community Protection Notices’ that can be used to silence or exclude such performers, or certain types of performance, from public spaces.

Perhaps, as a result of such positions on the margins of polite, or even acceptable, society, there are limitations to the extant source material that documents the history of street music. In turn, written histories of street music and the musicians that have played it are again somewhat limited. While there are some notable exceptions – for example, the quite substantial literature on the music of the Troubadours – in the main, art histories have not considered the bulk of these other itinerant performers in any great detail. This is understandable, though, given that the status of many of the performances I am referring to here as being ‘art’ is in itself often debated. It is interesting, equally, that street music only receives a couple of short mentions in David Hendy’s recent study of the history of sound and listening, Noise.[iv]

Such limitations noted, there are some useful historical records that can be found. For example, records of the performances and journeys undertaken by various forms of itinerant entertainers during the Tudor and Stuart periods can be considered thanks to their payments being noted in civic accounts. However, as suggested a moment ago, this only covers the more reputable performers. As Brayshay notes, “It is likely that entertainers offering earthier, less sophisticated shows are under-represented” in such records.[v] Being in the most part in the lower classes of society such musicians were not necessarily in a position to write their own history or even have their say on what was written about them. In fact, quite the contrary. As Sally Harrison-Pepper notes, “Much of the history of street performance…is found in the laws that prohibit it”[vi]. Much of the existing written history of street music takes the form of letters written by those complaining about the nuisance street music posed for them, and in the records of the debates that took place in the development of street music legislation.

With this complex history in mind, and recognizing the timeframe that a complete history would need to cover, I am not going to try to sketch out anything like a full or complete history of street music this evening. Rather, in this lecture I am going to discuss one particularly well-documented episode in this history of street music that ties into a range of the tensions I have just mentioned: namely the situation of street music in Victorian London. Due to a variety of reasons this is by far and away the most extensively documented period in the history of street music. The ‘street music problem’, as it was then called, emerged in light of the growing class of musical, medical, legal, and literary professionals – individuals with means and opportunities to voice their concerns, if not to escape them – for whom street music disrupted the quiet tenor of their home-working lives. This has left a range of interesting sources grouped around the mid-19th Century that give an insight into the uncertain situation of street musicians in the streets and squares of London.[vii] And as I will come to later, these sources also reveal quite how little the position of street music has changed in such environments given recent and on-going debates regarding street music in the City of London and surrounding boroughs, not to mention in other urban centres.

***

Before talking about the street music debates, it is important to set something of the sonic scene upon which they played out.

The 18th and 19th Centuries saw dramatic changes in the soundscapes of the United Kingdom. The Industrial Revolution in particular led to significant changes in the soundscapes of urban environments at this time.The increased necessity for factory-based work drew increasing numbers of people into one placeand the related growth in urban populations led to cramped (and often) unpleasantly noisy living conditions. The nature of the work undertaken in these factories itself produced a great deal of noise; the running of steam engines and hydraulic presses, the firing of pistons, the clanking of metal on metal, all produced an incessant din that could overwhelm the uninitiated observer and potentially deafen the factory worker.[viii] Alongside this, technological advances in sound amplification and recording led to the ability to mechanically reproduce sounds beyond their initial taking place and/or makes previously imperceptible sounds audible. This was,as Picker’s notes, “a period of unprecedented amplification, unheard of loudness…an age ‘alive with sound’”.[ix] Or as Schafer suggests, “The Industrial Revolution introduced a multitude of new sounds with unhappy consequences for many of the natural and human sounds which they tended to obscure”; it meant that “it [was] no longer possible to know what, if anything, is to be listened to”[x]. The clarity and definition of the pre-industrial soundscape really became a disorientating and indistinct noisescape at this time.

While for some such noise might have been a sign or symbol of industrious progress and with that the expanding vitality of life in the metropolis, for others this presented a very different situation. For a range of individuals, living amid such a soundscape risked the productivity, mental wellbeing, and even physiological health of the population.

***

And this brings us to the street music debates.

The debates had their origins in the 1840s when The Times began to publish regular letters complaining about street noise. As just noted, the Metropolis had become increasingly noisy during this time. While various measures were taken during this time to limit some sources of noises,[xi] from the start of the 1850’s and on into the 1860, attentions focused on one source amid this noisy scene that was deemed to be deserving of particular scrutiny: the street musicians. It was suggested that the noise made by such performers had become an extreme problem, and so it was the task of affected members of the public to “demonstrate what great obstacles are opposed by street music to the progress of art, science, and literature, and what torments are inflicted on the studious, the sensitive, and the afflicted”.[xii]

Echoing common Victorian proclivities, a common initial reaction to such street music and its sources of was to scrutinize it in great taxonomic detail. For example, Charles Babbage in his Chapter on Street Nuisances lists all of the “Instruments of torture permitted by the Government to be in daily and nightly use in the streets of London”.[xiii] These included: Organs, Brass Bands, Fiddles, Harps, Harpsichords, Hurdy-Gurdies, Flageolets, Drums, Bagpipes, Accordions, Halfpenny whistles, Tom-toms, and Trumpets. Beyond this, Babbage also articulates certain common associations between instruments and the performer themselves; so, organs are attributed to the Italians, Brass bands to the Germans, Tom-toms to the so-called Natives of India, Fiddles to the English, and so on. There was also some hierarchical organization to these taxonomies. We can get a sense of this from Charles Mamby-Smith who, writing in the Chambers Edinburgh Journal in 1852, proclaimed the following:

“Perhaps the pleasantest of all the out-door accessories of a London life are the strains of fugitive music which one hears in the quiet by-streets or suburban highways – strains born of the skill of some of our wandering artists, who, with flute, violin, harp, or brazen tube of various shape and designation, make the brick-walls of the busy city responsive with the echoes of harmony. Many a time and oft have we lingered entranced by the witchery of some street Orpheus, forgetful, not merely of all the troubles of existence, but of existence itself, until the last strain has ceased, and silence aroused us to the matter-of-fact world of business. … [This] we must pass over with this brief mention upon the present occasion; our business being with their numerous antitheses and would-be rivals – the incarnate nuisances who fill the air with discordant and fragmentary mutilations and distortions of heaven-born melody, to the distraction of educated ears and the perversion of the popular taste.

‘Music by handle’, as it has been facetiously termed, forms our present subject. This kind of harmony, which is not too often deserving of the name, still constitutes…by far the largest portion of the peripatetic minstrelsy of the metropolis. It would appear that these grinders of music…are distinguished from their praiseworthy exemplars, the musicians [just mentioned], by one remarkable, and to them perhaps very comfortable characteristic…they have ears, but no ear, though they would hardly be brought to acknowledge the fact.”[xiv]

The worst culprits, then, were very often deemed to be the numerous organ grinders to be found throughout the city streets. These were seen to be the most common of the street musicians; it was regularly claimed that there were in excess of 1000 organ grinders plying their trade in the city, though this number was thought to have dropped slightly by the 1870s.[xv] While there were a range of types of organ played, and some variations in those playing them, as Picker notes, it was “The Italian organ grinders [that] came to be seen as the repulsive source of virtually all noise in the city” and suggested that may at the time held the view that “their eradication [was] the task of every ‘Friend of Tranquillity’”.[xvi] Such street musicians were deemed to be the lowest of the low, based on both the quality of their contribution to this soundscape, but also in light of the questionable ways in which they were seen to conduct their performances.

With this increasing prominence of both street music and complaints against it, the case against street musicians reached its head with the street music debates in parliament across 1863 and 64. Here, an MP (and brewer), Michael T. Bass, brought to parliament an Act for the better regulation of street music in the metropolis that proposed to repeal a section of the Act for further improving the Police in and near the Metropolis. This text identified various problems with the existing legislation. For example, this had required the person complaining to be the affected householder (or a servant acting on their behalf). This meant lodgers, for example, had little standing in making a complaint. Further, as the legislation only made reference to ‘thoroughfares’, this risked implying the exclusion of cul-de-sacs or performances taking place in gardens, for example. Quite problematic also was that the offense be committed ‘within view’ of a constable for them to be taken into custody. All a street musician had to do, then, was not play their instrument when a constable arrived. Finally, particularly troublesome was the reference in the legislation for there to be ‘reasonable cause’ for the complaint. While illness was specifically mentioned, the ambiguity over what could been deemed reasonable effectively meant the legislation could not be enforced as police constables had received instructions late in 1959 to say that they should only remove street musicians where illness was the issue and that they should not remove them for other reasons without first reporting to their sergeant or station.

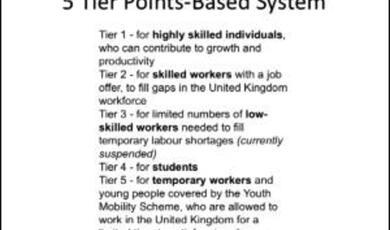

Figure 1: Bass’s role in the street music debates

Bass’s Act, which was passed in amended form in 1864, instead proposed that any householder or person acting on their behalf could complain and so demand that a musician leave their neighbourhood “on account of the Interruption of the ordinary Occupation of Pursuits of any Inmate of such House”.[xvii] While this was a lot clearer in terms of on what grounds complaints could be made and by whom, the degree to which this made a great deal of difference to the soundscapes of the Metropolis at this time is questionable. Street music was to be a feature of the soundscape of the Metropolis for some time to come and this persecution and very public ridicule of street musicians and actually ended up romanticising their presence and contribution for some commentators.[xviii]

During the time of the deliberations in Parliament, Bass published a collection relating to the street music nuisance, titled Street Music in the Metropolis. This brought together letters, official reports, materials from the press, and so on, much of which called for the outright banning of street music. The text itself is notable for the range of names that appear in it and for the way in which it, along with other comments from the time, gives a clear insight into one section of the public’s perceptions of street music and their clear distaste for it. Notable figures such as Charles Darwin and Charles Babbage contributed letters or comments to the collection. The remaining cast of contributors included lawyers, music tutors, composers, ministers, and members of other professions that in some way required home-based working, mental rather than physical labours, and the need for quiet to carry out their duties.

A number of themes come through in that text, and the debates more generally. The issues presented therein can be understood collectively in terms of the particularly intrusive nature of street music. Firstly, the most problematic performers – the foreign street musicians – were intruding into the country. Secondly, at the same time, many of these performers were seen to be intruding into the domestic spaces of the more respectable population through the noise they made. The capacity of sound to pass through obstacles, “its property of penetration and ubiquity”, meant there was literately nowhere to hide in these urban spaces, either public or private, from such street music.[xix] And this point about the ‘respectable’ population raised a third intrusion; clear class-based distinctions come through in these debates, with the majority of letters included coming from the emergent middle classes, and especially those working from home who wanted to have the streets made orderly and quiet to allow them to properly pursue their work and leisure activities. A clear message comes through: working-class tastes for organ-ground music played in the streets were intruding into the more refined sensibilities and spaces of the middle-classes.

In looking into these debates in more detail, the remainder of my discussion here will, then, be focused around two main themes. Firstly, I will talk about the portrayal of the performers themselves that were deemed to be so objectionable by those engaged in the street music debate, focusing on the tensions around national identity and class that permeated those discussions. And secondly, I will look to the content of their performances and the troubling sounds they made, which had such great impacts on the nerves of those forced to listen. Together, this should show the ways in which the identity politics of the time, and the properties of the sounds produced themselves, worked in concert in producing such disquiet around the presence of street music.

***

Focusing specifically on the organ grinders, throughout Street Music and the Metropolis, reference is made to them as being ‘Savoyard fiends’ or ‘blackguards’ that smelled of a combination of garlic and goat-skin, and that they lived in overcrowded conditions in Saffron Hill. Some of the specific language used here is instructive in that it shows the low views complainants held of these street musicians given that they would normally be used in reference to insects or other lower order creatures. It was suggested that they ‘infest’ the streets having brought a ‘certain vice from Italy’, or meant that the streets ‘swarm with vagabonds’.

Further, reference is regularly made to such performers being a part of an immoral slave trade as many were thought to work for ‘padrones’ who rented them their organ having shipped them over on the promise of work. These organ grinders then had to meet a daily target to be able to pay back this rent and to pay for their accommodation and subsistence, a potential justification for their reluctance to ‘move on’ (as opposed to some inherent immorality or lack of respect for those complaining). In fact, the banning of street music was thought by some be in the interest of the performers themselves. As one person suggested at the time:

“I conclude…that the reason we all bear it in silence is, that we think that if the law were to step in and abolish street music, a poor, honest, and industrious class would be deprived of the means of living. In this I imagine lies our mistake ... I am convinced that our Legislature could not pass any measure of more genuine humanity and charity than one which would prevent the importation…of those poor Italians into this country. They come, with scarcely any exception, to satisfy the greed of a few large speculators of their own nation. They are badly treated, ill-fed, and, into the bargain, cajoled out of the greater part of their hardly won earnings, before they return to their own homes, which many of them never reach”.[xx]

With less suggested sympathy, though, it was also argued that these immigrant performers should have lesser rights and so be suppressed more effectively given that those complaining were “surely subjects of the Queen, more than the Italian organ-grinder is, and I think it is not liberty but tyranny, if he is permitted to ply his vocation so as to make us desist from ours”.[xxi] There was very much a perceived distinction between who was in place, belonged, and had rights and who were ‘out of place’, did not belong, and so has few or no rights.

One of the clearest ways this otherness comes through is from the graphic representations of the organ grinders that appeared at the time. Most prominently, these appeared in the pages of Punch. The illustrator John Leech drew many of these in light of his own troubles with street music and the way in which this was perceived to negatively impact upon his health. These illustrations presented the grinders as variously dirty and sub-human, and Darwinian notions of evolution can be seen in such illustrations, as part of a general xenophobia directed towards these foreign invaders of both the country and the tranquillity of the Englishman’s home.

Figure 2: Darwinism and the foreign organ grinder

Figure 3: Streets swarming with grinders

Moving to the question of socio-economic class of these musicians, their audiences, and in terms of the class identity of those complaining, this proves to be a quite complicated issue. In the first instance, looking through the pages of Bass’s collection it is striking who it was that was actually complaining. As mentioned earlier, letters appear from some very notable figures of the time, including Charles Babbage, John Leech, and Charles Dickenson. We also have letters from doctors, clergymen, and even the Harpist to the Queen. This raises something of a tension in Bass’s case, though. Bass suggests early on in Street Music and the Metropolis that he received letters from all classes expressing thanks to him for taking up this issue and seeking to address it. However, on the very next page, he makes specific reference to the letters in his collection coming from members of the ‘learned professions’ and from ‘literary and scientific men’. The representativeness of his selection of letters as portraying the opinions of the population of London in general is, then, very up for debate.

For some in the collection, though, such lines of questioning were to be easily dismissed. A number of authors of the letters contained in Bass’s collection suggest themselves to be speaking on behalf of those lower classes that have confided in them their concerns. Here it is suggested that, for example, “if the inhabitants were polled, the vast majority, rich and poor, would vote against organs, whatever they might say about the kinds of music”.[xxii] It was not then a case of class-based differences in taste that was at issue, but that the music itself was played at all.

However, alternative impressions do come out from the debates. Street music is often regarded as being a democratic form of performance that is open to anyone, and, in particular, being open to those of limited means given that there is no charge for entry or to access a performance and as donations are voluntary. This is born out in the street music debates in that many of the letters sent to Bass suggest that it was in fact the support given to street music by such poorer members of society that meant the problem persisted. A number of letters in Bass’s collection do suggest that those with limited tastes were to blame for the ongoing presence of street musicians. Here, the greatest challenge to the campaign against street music was that “a large part of the community applauds and rewards those musical performances which cause to other persons annoyance, and perhaps misery”.[xxiii] This ‘rude majority’ did not, however, confine their questionable tastes to the confines of their homes, but instead chose to enjoy it in the public spaces of the city, and so impose their choice upon those others less well disposed to these performances.

Another way in which such class tensions were often framed in the debates was in terms of what (and by implication, who) was more important: was it the entertainment of the lower classes of society, and so those individuals, or was it the industriousness of the intellectuals in society. This was stated quite bluntly at times. For example, one letter commented that: “The abolition of street music is most earnestly desired by a large body of the inhabitants of London. Its retention is desired probably by a still larger section, but one really of comparatively little importance”.[xxiv] Here the former are connected to the authors, the artists, and so on that laboured for the public good. The latter were seen to be made up of “household servants, and others, whose wishes cannot surely be of any importance when weighed against” those of the classes just mentioned.[xxv] [xxvi]

Moving on to think more about the class of the performers themselves, while some of the activities of the street musicians and their supporters were confrontational and questionable in response to the complaints received against them, as Cohen and Greenwood note, “For many, street music was the last resort before begging or the workhouse, a fact that seems to have been ignored by its critics in the great public debates of the 1860s”.[xxvii] In many ways the accounts given throughout the debates paint a snobbish and unsympathetic portrait of a great number of people with little other option. This comes across most clearly in Henry Mayhew’s interviews with various street musicians recounted in his London Labour and the London Poor.[xxviii] And things really appear to be terribly desperate for many of these performers. In Mayhew’s text we hear, for example, from a French hurdy-gurdy player who was sold into slavery as a child and was subsequently a slave for 10 years prior to his current street music activities. We also hear from a blind harp player who was regularly bulled by boys and had his harp vandalized meaning he could not play.[xxix] It is not necessarily the case then that these performances intended to disrupt the orders of the Victorian city with their music. They were not necessarily nasty or immoral people. Rather, their performances were simply part of the attempts of some of the city’s least fortunate residents to get by or maintain the precarious life they led.

***

In thinking about the street music problem, while ‘concerns’ were raised about the performers themselves, it is important also to consider the music that way played. If anything the portrayal of the performers just discussed was articulated to add weight to the principle issue of concern here: the disturbance cause by street music. Though opposing views existed here, one aspect of this related to taste. Even though performers from the time commented on the need to have a repertoire that would engage various members of the population, ultimately the music being played was not that which at least some of the middle class complainants wanted to listen to. However, there was more to it than this. It was not so much an issue of what was played, but rather how it was played. The questionable harmony, the piercing tone, the volume, and the frequency and/or repetition were identified as fundamental issues with this street music, and specifically that of the organ grinder. Such discordant mechanically reproduced sounds were particularly affective when it came to the impact they had upon the listener and the sorts of disposition towards the music played it produced.[xxx]

To return to Mamby-Smith for a moment, we get an evocative description of the organ grinder’s sound that those complaining as part of the street music debates found so disturbing. The grinding of organs was felt to be made up of:

“The piercing notes of a score of shrill fifes, the squall of as many clarions, the hoarse bray of a legion of tin trumpets, the angry and fitful snort of a brigade of rugged bassoons, the unintermitting rattle of a dozen or more deafening drums, the clang of bells firing in peals, the boom of gongs, with the sepulchral roar of some unknown contrivance for bass, so deep that you almost count the vibrations of each note…”.[xxxi]

In thinking about the particularly affective nature of such sounds produced by street musicians, Charles Babbage’s comments from the time stand out based on both their extent and veracity. The scale and vigour of his complaints won him something of a following at the time. As he stated:

“I have developed…an unenviable celebrity, not by anything I have done, but simply by a determined resistance to the tyranny of the lowest mob, whose love, not of music, but of the most discordant noises, is so great that it insists upon enjoying it at all hours in every street”.[xxxii]

This ‘mob’ took various steps to show their disagreement with his actions ranging from displaying placards in shop windows near his home, to posting him threats, to breaking his windows, to throwing dead cats into his garden. Equally, during his attempts to have a street musician stopped by the police, a large crowd would often form and follow him to the police station, shouting abuse at him as they went.

As I mentioned, though, a central theme in Babbage’s account relates to the physiological affect that street music could have on those forced to listen to it. Babbage argued that:

“Those who possess an impaired bodily frame, and whose misery might be alleviated by good music at proper intervals, are absolutely driven to distraction by the vile and discordant music of the streets waking them, at all hours in the midst of that temporary repose so necessary for confirmed invalids”.[xxxiii]

Babbage’s concerns were not however purely philanthropic toward the sick or infirm. His concerns were much closer to home. Babbage claimed that:

“On a careful retrospect of the last dozen years of my life, I have arrived at the conclusion that…one-fourth part of my working power has been destroyed by the nuisance against which I have protested” and that “Twenty-five per cent is rather too large an additional income-tax upon the brain of the intellectual workers of this country, to be levied by permission of the Government, and squandered upon its most worthless classes”.[xxxiv]

Leaving aside the class laden rhetoric of this last comment, this clearly shows the physical impact of the music on the body listening. Babbage notes that his capacities to perform certain tasks were diminished as a result of the disruptive effect of the music and his desire to protest as a result.

Taking a step back from the specific content of some of these comments, an overarching theme amongst those complaining about the way they were affected physically by such sounds seemed to relate to their disposition towards the arrival of such sounds in the first place. This was often discussed in terms of how it affected their ‘nerves’ or them having a particularly fragile or strained ‘nervous disposition’. As one author in Bass’s collection noted:

“To those like myself, in such health as over-worked citizens can be, with the nerves in constant tension, a ‘reasonable cause’ [for requesting the music cease], is tomfoolery. I go home from the City, the brain overwrought, feverish, and fatigued, and I require rest and change of occupation – reading, writing, and music – and these are impossible with the horrible street music from all sides – the very atmosphere impregnated with that thrice cursed droning noise – that abomination of London which makes me ill, which positively shortens my life from the nervous fever it engenders”.[xxxv]

Thinking around this further, we can turn to what is now a classical sociological text that considered the sorts of sensory changes taking place in society during the 19th century: Georg Simmel’s The Metropolis and Mental Life. In this Simmel reflected on the effects of this increasingly and constantly stimulating nature of city life on the emotional life of individuals. From that, Simmel suggested that to cope with this, the individual needed to make adaptations to their comportment. This meant adopting a ‘blasé outlook’, a distanced or indifferent disposition, whereby the individual’s nerves adjusted themselves so as to ‘renounce response’ to the intense experiences they undergo in the metropolis.

Although Simmel was writing roughly 40 years after the street music debates, I think there are some interesting parallels here regarding the experience of organ ground music and the dispositions those subjected to these sounds adopted. In developing such an extreme aversion to the music played, and in making such a repeated conscious, even obsessive, response to it, it appears that Babbage and others failed to develop the blasé persona that Simmel talks of. We could argue though that this failure resulted in part from the fact that these middle-class residents had nowhere to retreat from the over-stimulation of the metropolis’s streets; such inhabitants of the city had no possibility to develop any literal distance from which they could relax their nerves or allow such tensions to dissipate. Either, as Pickers notes, “In assaulting the hearth, the … organ grinding denied [them]…the pursuit of ‘rest’ so essential to the life of proper gentlemen” or worse, for those without an office, it presented a risk for both their work and leisure.[xxxvi] Either way, not only did they face the constant stimulation of the metropolitan environment, the sonic aspects of the stimuli also impeded into their homes, into, quote “the very recesses of the ‘Englishman’s castle’”.[xxxvii]

***

Hopefully, from this account it is clear that street musicians held a rather marginal and contentious position in the streets of Victorian London, both on the basis of who they were and what they played. To conclude, then, I just want to highlight a couple of connections and points of continuity with regards to the present situation of street music in the metropolis today.

Firstly, while I situated the Victorian street music debates in the context of the sonic changes that took place in light of the Industrial Revolution, and concerns over the increasing noise produced by that specifically, today’s street music happens within the aftermath of another revolution: the Electric Revolution. This, again, has been shown to have significant implications for urban soundscapes in terms of noise.[xxxviii] In some ways, cities have become louder, both in terms of volume but also in terms of duration. We have many more sources of noise and we have a greater range of technologies that allow us to make things heard. And of great relevance here in the context of street music, is that the sounds of the barrel organ have been replaced by the sounds of guitar, voice, or other instrument being amplified by battery powered amplifiers – the most common target of any contemporary street music debate. As such, complaints about street music continue, again principally on the grounds of its disruption to both commerce and leisure. So much has changed here, but so little has changed also.

Secondly, we have the legislative situation of street music. While there have been a range of developments in terms of how noise is regulated in urban environments in the intervening years since the street music debates – perhaps most obviously through statutory nuisance legislation which is often invoked in response to complaints about the presence of street musicians and the music they play – we have something of an ironic situation in London today, when it comes to legislation specifically orientated towards street music. Today street music is actually governed by legislation put in place prior to the street music debates discussed here, specifically section 54, paragraph 14 of the Metropolitan Police act of 1839. This effectively bans street music, stating that:

“Every person shall be liable to a penalty ... who, within the limits of the metropolitan police district, shall in any thoroughfare or public place, … blow any horn or use any other noisy instrument, for the purpose of calling persons together, or of announcing any show or entertainment, or for the purpose of hawking, selling, distributing, or collecting any article whatsoever, or of obtaining money or alms”[xxxix]

So, in quite literal terms, though with some small exceptions, the situation of street music in the metropolis today and any debates taking place relating to it, play out from something of a Victorian starting point.

© Dr Paul Simpson, 09 July 2015.

[i]Brayshay, M. (2005) Waits, musicians, bearwards and players: the inter-urban road travel and performances of itinerant entertainers in sixteenth and seventeenth century England. Journal of Historical Geography 31 pp. 430-458.

[ii]Simpson, P. (2008) Chronic Everyday Life: Rhythmanalysing Street Performance. Social and Cultural Geography 9 pp. 807-829.

[iii]Cresswell, T. (2006) On the Move: Mobility in the Modern Western World. Routledge, London (p11).

[iv]Hendy, D. (2014) Noise: A Human History of Sound and Listening. Profile Books, London.

[v]Brayshay ‘Waits…’ p432.

[vi]Harrison-Pepper, S. (1990) Drawing a Circle in the Square: Street Performing in New York’s Washington Square. University Press of Mississippi, London (p22).

[vii]Babbage, C. (1864) Passages in the Life of a Philosopher. Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, and Green, London. Bass, M.T. (1864) Street Music in the Metropolis. John Murray, London. Mayhew, H. (1968 [1861]) London Labour and the London Poor (Vol. 3). Dover, New York.

[viii]Hendy ‘Noise…’.

[ix]Picker, J. (2003) Victorian Soundscapes. Oxford University Press, Oxford (p4).

[x]Schafer, R. M. (1977) The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World. Destiny Books, Vermont (p71).

[xi]Bass ‘Street Music…’ (p105)

[xii]Bass ‘Street Music…’ (p vii).

[xiii]Babbage ‘Passages…’ (p 4).

[xiv]Mamby-Smith, C. (1852) Music-grinders of the Metropolis. Chambers Edinburgh Journal, No. 430 (p1-3).

[xv]Greenwood, J. (1874) In Strange Company – The Organ Grinder. Accessed at http://www.victorianlondon.org/publications4/strange-08.htm; Bass ‘Street Music…’.

[xvi]Picker ‘Victorian…’ (p43).

[xvii]House of Commons (1864) Act for the better regulation of street music in the metropolis.

[xviii]Picker ‘Victorian…’

[xix]Nancy, J-L. (2007) Listening. Fordham University Press, New York (p13)

[xx]Bass ‘Street Music…’ (p59).

[xxi]Bass ‘Street Music…’ (p37).

[xxii]Bass ‘Street Music…’ (p12).

[xxiii]Bass ‘Street Music…’ (p54).

[xxiv]Bass ‘Street Music…’ (p33).

[xxv]Bass ‘Street Music…’ (p33).

[xxvi]Sala, A. G. (1859) Twice Round the Clock, or The Hours of the Day and Night in London. Accessed at: http://www.victorianlondon.org/publications/sala.htm

[xxvii]Cohen and Greenwood ‘The Buskers…’ (p135).

[xxviii]Mayhew ‘London Labour…’.

[xxix]Mayhew ‘London Labour…’ (p174).

[xxx]Goodman, S. (2010) Sonic Warfare: Sound, Affect and the Ecology of Fear. MIT Press, Massachusetts (p. xiv and xvii).

[xxxi]Mamby-Smith ‘Music-grinders…’

[xxxii]Babbage ‘Passages…’ (p11).

[xxxiii]Babbage ‘Passages…’ (p6).

[xxxiv]Babbage ‘Passages…’ (p11).

[xxxv]Bass ‘Street Music…’ (p8-9).

[xxxvi]Picker ‘Victorian…’ (p53).

[xxxvii]Babbage ‘Passages…’ (p25).

[xxxviii]Schafer ‘The Soundscape…’

[xxxix]From: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Vict/2-3/47/section/54.

Part of:

This event was on Thu, 09 Jul 2015

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham College plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login