The Idea of the North

Share

- Details

- Text

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

The idea of the North lies at the intersection of poetry, myth, art and the myriad ways in which artists, poets and explorers have filtered the north's stark natural splendour through their imaginations. The author, Peter Davidson, offers a route through the various shapes the North has taken in the minds of humans, be it a 'North' which is the other end of town, Manchester, or the Arctic Circle.

Download Text

The Idea of the North

City of London Festival 2009

by Peter Davidson 19 June 2009

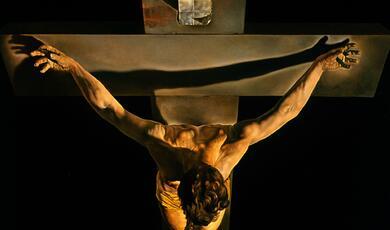

Snowlight and Evening: The Fall of Northern LightIf I were at home in Aberdeenshire in the evening of a day so near to midsummer as today, the daylight would be undiminished until about ten. It would feel as if time itself were stretching and slowing in the endless northern evening. It is difficult to exaggerate the way in which the presence and absence of light governs the life of the north. On such an evening it is hard to stay in the house, hard to waste the daylight, because in the north you are always aware of the dark biding its time. In a week or two, the prodigious light will already be dwindling: in the words of that splendidly miserable old sod Professor Housman The dark Has passed its nadir and begun to climb. We would go out just as, at last, the sun begins to go down. Out into the cooling air and the level light, into the scents of the clove pinks in the bed beside the greenhouse. Viridian shadows are beginning to deepen under the trees on the lawn. We walk away from the house, between the beech hedges which lead out of the clearing at the end of the garden, and down the broad steps into the wood. A grass path stretches away to the north of us, into the sunlight which still sends its last low rays over the stream and amongst the trunks of the trees. The floor of the wood is thick with ferns; self-sown foxgloves stand beside the winding path. This is the time of the June night loved by the northern Romantic painters of the early nineteenth century, this peaceful evening offering its glimpse of the otherworld, the physical landscape of twilight opening out into spiritual territories of the imagination. The sun is setting now behind the trunks of the trees to the north: gold and vermilion float and dissolve in the blue air. It is almost exactly the light of Caspar David Friedrich's painting Evening in the museum at Hanover, and we might almost be standing amongst the ferns and flowers in his foreground, where he places two figures. But the light is so faint under his trees that the figures are themselves little more than grey shadows amongst shadowed green. Or we could be in another northern wood with a belated glimpse of midsummer sky: in John Sell Cotman's Duncombe Park in the Tate Britain, one of the sequence of experimental wilderness paintings which he made on his tour of the north of England in 1805. Both Friedrich and Cotman delighted in painting obscure places, retired places, even disappointing places, and transforming them by their concentration on what the light reveals or conceals. After the turmoil of wars and revolutions which brought the noontide certainties of the eighteenth century to an end, all the arts seem to have turned together to the celebration of twilight' think of the flowing melancholy of the Nocturnes of the Irish composer John Field. But all these arts of twilight, we might reflect, flowered in the north of Europe. All Romantic artists shared, to some extent, their time's intensity of feeling about light and landscape: engaging in a passionate colloquy with place, as though it could answer them, respond to them, instruct them. But how different Friedrich's woodland sunset is from Cotman's. Friedrich's bears a precise weight of religious allegory, where Cotman's invests personal emotion in the memory of his solitary walk amongst the trees under the fading sky. For Friedrich, sunset is the paradise to which the shadowed walkers are travelling. The fence of tree-trunks and the rising powder-blue mists from the valley beyond are the barrier of years and their illusions which stand in the way of the couple's journey together to the bright regions of the evening sky. This is another essential distinction of north and south: southern artists can make their paradise-gardens on earth, lit by the lamps of the orange-trees, by Virgilian sunsets. For northern artists, paradise is removed to the clouds or composed in the distant mountains by the evening light. (The implications of this for the religious sensibilities of north and south would reward investigation richly.) This kind of allegorical landscape comes to Friedrich and other painters of the north so naturally that it is as if their painting is simply giving form to the shared feelings of a generation and a region. And so we watch the sunset between the boughs and the slow evening wears on almost imperceptibly towards midnight. At the end of the wood we take the path that leads up the hill behind the house. Coming out into the hilltop field, we can turn and look to the north at last. Although we are on the 57th parallel, just short of the magical 60 degrees, where it is truly twilight all night long, we are still very much in the region of the white nights, the antechamber of the true north. You see this, looking north past the stone farms and the little pinewoods as the land rolls away towards the coast. The sky is still a pale blue from horizon to zenith - the fullest expansion of the brilliant line of light which is scored along the northern horizon for a month either side of midsummer night. Tree branches and hills stand out in clear silhouette against it. And, magically and only at this height of the summer, there is a glimmer of amber above the horizon, a diffused red along the profile of the hills. It is the distant reflection of the sun at midnight, the bright sky over Shetland, the absolute north of the absolute light and dark. Turning back downhill towards the house I think of a friend's house on the mainland of Shetland, a long whitewashed house near the sea. The light will be bright enough there to read outside at midnight. Treeless slopes, scattered houses, stone beaches, the wind never quite sleeping. The true north defined by the light in the sky above, reddened by the sun just below the horizon, what is called there 'the simmer dim'. The red glimmer on our horizon is the reflection of the true north, the same way that on clear summer nights from the north coast of Aberdeenshire the mountains around Helmsdale, far to the north, appear suddenly against the horizon like a territory risen from the sea, like an otherworld. North and further north. Let us think for a moment about the north and think too about the geography of the twilight, about the history and topograpy of light and dark. The more you think about the word 'north' the more that it seems term which will always be relative. There are always other norths beyond the north you inhabit, until eventually you come to the unnegotiable north of the icecaps and the pole. Proverbially 'north' is an unstable idea, an idea that moves away from you, eludes you, 'north' is so often 'north of here', receding and shifting and passing out of reach. North is almost always north of where you stand. Of all geographical terms, it is the most personal, the most emotional, the most elusive. And perhaps the one which evokes the most powerful feelings. There are many imaginary lines on the maps which have been regarded over the centuries as the frontiers of the north - or at least of one version of north, one attempt to fix an elusive idea to a firm geography. I am always haunted by the Chinese legend that a northbound explorer found eventually in the unvisited desolation of the Steppes two great pillars placed there by the omniscient ancients, with an inscription proclaiming them to be the gates of the cold. I have a purely private notch in the hills at the head of Glen Shee, just where it narrows towards Braemar in a recession of mountain slopes of which any nineteenth century painter would have been proud, which is my own gate of the north, the boundary of the remote, dissident, fathomlessly civilised counties of Aberdeen and Moray. By the time he turned twenty, the poet W.H. Auden had already decided that the north began where English brick gave way to stone, where hedges gave way to dry-stone walls. There are other frontiers - Latin languages giving way to Germanic ones. Butter rather than olive oil, fish as a staple rather than meat, wheat giving way to rye. The weather map is often a map of north and south, and schematic snowflakes and black clouds define the north. Canada defines the north administratively as beginning at the sixtieth parallel. Timber and stone as building materials. Broadleaf giving way to conifers giving way to tundra giving way to the haunting landscapes of lava and stone which flower briefly and unforgettably in the meltwater of the month-long arctic summer. The ancient boundaries of the Roman Empire still surface from time to time in the European consciousness as a frontier of the north. England and Lowland Scotland spent a good deal of their eighteenth centuries affirming inclusion within that frontier. The lonely five-peaked mountain which dominates the skyline of Aberdeenshire, Benneachie also known as Mons Graupius, is the farthest north which the Empire's armies reached before the Picts and the shadowy tangle of the northern forests were too many for them. We could go on multiplying relative frontiers of the north, but I would like to advance one unmistakable marker of northness on which probably all can agree, and that is the fall of the light and the presence and absence of light in the round of the year. The long midsummer evenings from which I began are uniquely of the north, as are those midwinter days which you get even in London when the sky never seems to have been switched on properly. Exploring this idea of the north as defined by light, the 60th parallel takes on an immense importance as lying more or less at the midpoint of those latitudes which experience to some degree what I feel to be a distinctly northern pattern of light. Ten degrees either side of the sixtieth parallel, to a greater or lesser degree, experience those contrasts of light and dark and, crucially, those twilights which shape and define the north. So the 60th parallel is the meridian of the half-lights, the long evenings, the protracted melancholy sunsets (northern winter days ending in damp and frozen air) which stretch from about 50 degrees to 70 degrees. At seventy degrees and beyond the north is the frontline of the battle of the light and the dark. Thinking about the arts of the north, the 60th parallel is nearly a centre-line, from 50 to 74 might be said to encompass the inhabited north, all places where awareness of light is not only essential and formative, but the foundation of modes of feeling which find expression in all the arts, but most especially the visual arts. These latitudes are the realms of the twilight: all these territories have some degree of twilight rather than darkness all through the night at midsummer. The white nights - a wonderfully precise phrase. To the north of this, (north across the skerries and the islands, far beyond the reflected simmer dim of the Shetlands and the Faeroes) are the shadowless, lucid midnights of Tromsø and their dark corollary in the mirk-tide of winter. Arctic north, absolute north is defined in the absolutes of light and dark. South of the fiftieth parallel are the territories of true darkness at midsummer, the year-round equipoise of night and day, short twilights, the noonday demon of the August sun. Heat and light can be the enemy here, the hours of darkness - la madrugada - the time of release and pleasure. No twilight, said Coleridge, in the courts of the sun. I don't know if you are familiar with the science of twilight. Its definitions are memorable, delightful. When the sun has just dipped below the horizon, up to 6 degrees below, and when the first stars are just visible, is civil twilight, the blue hour beloved of nineteenth century French writers and painters. This is the time when the white flowers in a summer garden jump forward to the eye, when a whitewashed house on a winter hill shines out of the dimness. When the sun is six to twelve degrees below the horizon, it is nautical twilight, darkening cobalt on a clear night, at the end of which the horizon line is no longer defined by visible brightness. From twelve to eighteen degrees below the horizon, it is astronomical twilight, apparently dark to the casual observer, to whose eye the constellations are as bright as they would be in full darkness. The defining twilights of the north manifest themselves not only as long evenings, absence of complete darkness at night, but also as states of light which can last for days and weeks. I'll attempt a summary geography of twilight, trying for concision, but trying also to be clear. Twilight lasts the longer the further north (or of course south) you are. Polar twilight can last for a fortnight, coming in and out of the mirk-tide of midwinter. In the territories ten degrees either side of the sixtieth parallel the twilights of midsummer and midwinter are the longest, emphasising thereby the emotional and, I suppose, psychological effects of unignorable changing seasons. Civil twilight lasts all night at midsummer at 60 degrees - that glimmer of redness in the northern sky seen from the north of this island. Nautical twilight lasts through the midsummer night at 54 degrees north, astronomical twilight at forty-eight degrees. Civil twilight over Shetland; nautical twilight over Newcastle and the Scottish Border; when the sky grows dark on midsummer night over London, it is actually astronomical twilight. I would like to talk in a little while about the realm of twilight, 'evenings of late autumn, sad enough to pierce the heart . . . a nostalgia for things we never knew, anguish of the turn of the year, the time of impotent yearning, the inconsolable season' in the beautiful words of Angela Carter. But first let us think for a moment about the mirk nights, as the Scottish ghost-ballad puts it. The long winter dark inevitably works a profound and essential change in the way people think. It is as thought the otherworld and its terrors was loose on earth for its duration. The Icelandic sagas are full of ghosts in the twilight and the dark, and the malign after-walkers are at their strongest when the sun is weakest. In the Saga of Grettir the strong, the malign, corporeal ghost of the pagan Glam is defeated by the hero, but places on him the effective curse that he will see the phantom's eyes in front of his own eyes whenever it grows dark. So that the visitation upon the accursed Grettir lasts the whole of the mirk-tide of midwinter, so that 'Gettir dared to go nowhere alone after nightfall, the dark was so full of horrors for him.' This curse seems wholly unjust: Grettir has rescued an innocent family from the malign revenant, after all. Sara Maitland points out that Norse mythology is the exception amongst European mythologies. In pre-Christian Scandinavia the victory of the light at the last day is not assumed. It remains wholly possible in minds used to the black trough of the dead year for a fortnight and more either side of the winter solstice, that the dark will win the last battle. Norse mythology is the only theistic theology I know of where the issue remains in serious peril. The gods will go out to fight at Ragnarok. They will do their best for themselves, for humans, and for the light; but Baldur the Beautiful is dead and we do not know if they or the forces of the dark will triumph. Grim hints in the Poetic Eddas suggest that both the sun and the father of the gods will be devoured by the Fenris wolf, at the last battle. It has been suggested that the mitigating prophecy that Odin will be avenged and the sun may have a daughter to shine on the unimaginable world of the future are retrospective interpolations by a Christian editor of pre-Christian material. What this mediaeval editor, Snorri Sturlusson, is doing is trying to show that his own northern people were natural Christians, whose chthonic mythology held seeds of the truth, and thus he makes of their pagan last battle something of a parallel to the sun darkened at the Crucifixion, darkness as prologue to triumphal light. It is possible that this parallelism of the last battle of dark and light in Norse mythology with the Crucifixion and Resurrection form the subject of what I like to think of as the seminal work of northern English art: the relief-sculptured cross, dating from about 940 still in the churchyard at Gosforth in Cumbria. I would like to venture the argument that this northern work of art inevitably concerns itself with the light and the dark. The Gosforth cross is one of those absolutely compelling works of hybrid art which can embody two sets of meanings, two world-views, at the same time, and interpretation depends entirely on the mental positioning of the beholder. (The world of the seventeenth century, the aftermath of the age of voyages and contacts, is rich in such bilingual works of art, double in style as in signification). At Gosforth there is a battle, with one warrior, as it might be 'the champion Christ' menaced by the jaws of Hell-mouth or fighting the Fenris Wolf who will devour Odin himself and consume the sun. There is also a carving of a radiant young man with outstretched arms who is Baldur reborn or Christ resurrected. Perhaps it is more accurate to say that he is Baldur reborn and Christ resurrected. The shadows of the relief carving on the Gosforth Cross have grown shallower with a millennium of the wind and the rain, but it remains today a work about the light and the dark, about the battle of the unconquered sun with the winter, even if we know (in this instance) better than Wagner that Ragnarök means the judgement or ordeal rather than the twilight of the gods. * I wish that we had time to think at length of all the qualities of northern light. I have written elsewhere of the chandeliers and mirrors of the north, the great leaves of crystal which hang at the ends of the enfilades of rooms in manor-houses in Scandinavia, as much for their ability to catch the falling western light of autumn as for their ability to refract the candles which are lit at the mid-afternoon nightfall of winter. I should also touch in passing on the way that the low light of autumn and winter has influenced the disposition of northern rooms. With the midwinter sun shooting cold clear light from its position just above the horizon, no wonder that the colour of so many Scandinavian rooms is grey - that merciless light finds undertones of pink and brown in any broken white, brightness turns muddy under its remorseless searchlight. Snowlight is another wonder - like the summer evening it is a northern light which seems to have almost a metaphysical dimension. The Dutch poet Martinus Nijhof wrote of a winter morning in the Hague De wereld is herboren na dit sneeuwen, En ik bin weer een kind na deze nacht. [And through the snow our fallen world's reborn/And I a child again, born of this night.] It is indeed one of the otherworldly modes of the north to waken on a winter morning to an unaccustomed brightness striking upwards, and, once curtains are opened, to see the ceiling scattered with rainbows as the light strikes upwards through the prisms of a chandelier. The vigorous renaissance painting on the beam and plank ceilings of Scottish castles has its effect by candlelight and by summer daylight, but it comes into its own in snowlight, the upward light giving a movement and richness to patterned beams, to panels of emblems and imprese, to the diapering which looks like brocade on such winter mornings with the white fields stretching away on every hand. The light of the northern midwinter lies in long ladders on pale scrubbed floorboards all through Scandinavia, another aspect of the decoration of Scandinavian houses, like grey panelling and snow-white ceilings, to some extent governed by the reception of northern light as much as by the economics of carpets and textiles. The long winter nights too enforce and aesthetic of lamplight, most beautifully explored by the Norwegian painters of the turn of the twentieth century. And so I come to rest on my final focus for these thoughts on the north: northern twilight and its representations in the visual arts. My last regret is that we have no time here to trace the evolution of the painting of twilight from Giotto's night-piece of The Betrayal of Christ whose black sky is still lit by an imagined frontal daylight, through the experimental moonlights and sunsets (even fireworks) of the Netherlandic painters of the seventeenth century, to the sinister, purple and gray southern twilights of that exponent of the darkest baroque, Mihiel Sweerts, and on from those to the flooding, paradisal sunsets of Poussin and Guercino. Let us return to the romantic era where we began, when the painting of twilight became an expression of an apprehension of spiritualised landscape as well as an attempt to glimpse a metaphysical territory lying just out of reach in the northern evening. And so we come again to the great north- German master of the twilight, Caspar David Friedrich, with his freezing winter afternoon going to dark over the ruins of the abbey. This seems a painting of buried faith, the way that his celebrated sea of ice in Hamburg is a painting of dead hopes, of the freezing of revolutionary Europe with the return of the ancien regime. We see too his Evening in the northern wood from which we began, as a serious attempt to paint the landscape beyond the landscape, the allegorical landscape lying just below the visible landscape, the paradise which is located (like Wordsworth's cloud-heaven in The Excursion) in the territories of the sunset. Or we have in Friedrich's Moonrise by the Sea almost a composite evening light which holds some of the apricot-colour of the departing sun although the moon is already rising. I was talking to the distinguished Scottish landscape painter James Morrison about this a couple of weeks ago and he said that he thought that Friedrich's evening skies, like the skies in his own paintings, are to some extent less a facsimile of one moment than a record of the changes of light over the time that it took to make the initial notations for the painting. A thought worth taking forward into further considerations of northern evenings. Friedrich's spiritualised landscape had a clear effect on his contemporary Johan Christian Dahl, as we can see in this 1830 Evening by the Seashore, which is almost composed of reminiscences of Friedrich (note the purely emblematic anchor of hope that the wished-for ship will return) as is this less sombre Mother and Child by the Sea. Dahl carried Friedrich's compositions and thoughts northwards: his Copenhagen Harbour by Moonlight is a different aspect of the northern night: the chill brilliance of the winter moon. Dahl's Norwegian pupil Thomas Fearnley, active in the first half of the nineteenth century, carries his and Friedrich's techniques and ideas further north still, into the Norwegian countryside. The sheer force of the mountain river falling over stone in his Labrofossen is beginning to be more a transcription of a wonderful reality than a metaphysical landscape, although his wonderful clearing stormlight over a fjord with minute sails on it, is a magnification of Friedrich and Dahl's significant placing of figure in landscape - here the landscape is overwhelming in scale, grandeur and light. His great tree against the sunset sky is a transformation of the evening silhouettes of Dahl and Friedrich into something which is altogether more overwhelming in scale, again the proportion of the picture-space taken up by the figures is comparatively small, the northern evening immense. Evening melancholy is a characteristic of the northern zone of the long twilights, as in the mid-Victorian Scottish painter Alexander Dyce, whose transformation of the planted woodlands of a Scottish castle in the after-light of an early summer evening into the Garden of Gethsemane is achieved by the addition of the bowed figure of Christ. And Dyce's Pegwell Bay is a wholly familiar image of the end of a holiday day, the figures somehow rather detached from each other, the light beginning to go, happiness suddenly seeing fugitive and circumscribed with the chill falling on the seashore. Rather than melancholy, the innovative Norwegian painter Peder Balke finds a kind of dark exhilaration in his landscapes of the extreme north of Norway. His beams of summer light over the north cape are shadowed by the kind of dark cloud which can funnel down from the mountains bearing snow at such an extreme latitude, even on a still and lucent May night. His sunset over snowy hills and the dun flat foreground are a transcription of the sheer lateness and fragility of the northern summer. Past the seventieth parallel the brown grass only emerges from the deep snows in May when the daylight is already lasting through the night. As is evoked in gentler mode, further south, nearer to the sixtieth parallel, by Harald Sohlberg in his paradisal field of white flowers lit by a white night light, and his wholly evocative House by the shore with pines in the foreground on a midsummer night of serene brightness. How much this image reminds us of the great twentieth century evocation of the northern lands and their light, Nabokov's twisting, labyrinthine account of a dream kingdom in the far north, Pale Fire. In that novel the dream-king, the dream-exiled king concentrates the essence of his memories (and therefore of Nabokov's own memories of his lost Russia) into the scent of heliotrope and a 'wooden house by water', just as in Sohlberg's painting. In complete contrast we turn to the most recognisable images of the sadness of autumnal England, the urban melancholy of the Victorian north. Winter skies of ivory and umber, streetlamps and bare trees, city sunsets of smoke in frozen air. Somehow the response to these images is a kind of weary acceptance, an emotion of recognition. As with the early sunlight diffused by the cold into a generalised wash of pale gold. As with one of Grimshaw's familiar, aching images of lighted windows and the early dark, another painting where in fact the light seems more a record of time passing than a transcription of a single moment. Of course the urban evening of the nineteenth century can show a kind of gallantry or elegance as with Whistler's cobalt London night and the fall of the rocket from the other shore of the river. Or as with an immensely evocative but little-known work by the Orcadian painter Cursiter, painting himself and his family as they were when he was director of the National Galleries in Edinburgh. A curious, beguiling combination of elegance and melancholy, the family in the opulent interior in evening dress, but the street outside saturated and glimmering with the rain, the cobbles turned mirror, almost turned canal. And the low light, the rain outside dominating it and shadowing it all. One of the most persuasive images of the monochrome of winter London was painted in the early years of the twentieth century by the Danish painter Vilhelm Hammershøi: the absolute restraint of his palette here evokes the absence of light, that northern light which is a negative, an absence, a lack. And the wonderful sculptural quality of the great iron railings and the cold in the air. Hammershøi is most celebrated as a master of the fading light in his depictions of the interiors of the various Copenhagen flats in which he and his family lived. Occasionally these show a bright morning throwing sunlight across Biedermeyer furniture and grey-painted panelling. But usually these are evening pictures, some of the most haunting depictions of the northern light and its fall. They are often extraordinary experiments with the very last of the light, the ebbing of definition from grey things, the catching of a sliver of belated reflection on the moulding of a panel or along the bevel of a mirror. Sometimes in his paintings it has grown so late that the only light in the room comes from the streetlight outside. And, almost always, the figure of his wife has her back to us like the figures in Friedrich's metaphysical landscapes of the evening. Melancholy, silence, evening. The last of the light over the quay and the inlets of the Baltic with the Greenland icebreakers lying at anchor almost under the windows. And so we move to an end with a poignant English image from wartime, Captain Ravilious of the Marines painting Norwegian snow and midnight sun, from beyond Tromsø, which austere landscape he saw as his own paradise or otherworld, in which austere landscape he died when his plane was lost off Iceland. But I would like to end with repose and contemplation of the serenity of the northern evening, with this image by the contemporary artist Tim Brennan, the almost-abstract late-evening colours of the sea - stillness under the white nights of high summer. Absolute quiet, absolute remoteness, as the northern shore of Scotland would be tonight were I at home in the north on this midsummer evening.

© Peter Davidson, 19 June 2009

Policy and Objectives An independently-funded institution, Gresham College exists to continue the free public lectures which have been given for over 400 years, and to reinterpret the 'new learning' of Sir Thomas Gresham's day in contemporary terms; to engage in study, teaching and research, particularly in those disciplines represented by the Gresham Professors; to foster academic consideration of contemporary problems; to challenge those who live or work in the City of London to engage in intellectual debate on those subjects in which the City has a proper concern, and to provide a window on the City for learned societies, both national and international. Gresham College Barnard's Inn Hall Holborn London EC1N 2HH www.gresham.ac.uk 020 7831 0575 e-mail enquiries@gresham.ac.uk Gresham College is generously sponsored by the Worshipful Company of Mercers and the City of London Corporation as part of their wider contribution to the cultural life of London and the nation. www.cityoflondon.gov.uk The City of London Corporation and the Mercers' Company are committed to promoting learning and development, and to ensuring equality of opportunity for all. The free public lectures provided by Gresham College professors and the seminars, conferences and webcasts the college hosts play an important part in it achieving these aims. The City of London Corporation is proud of its association with Gresham College and with the Mercers' Company which also provides essential support, enabling the College to thrive and flourish. Reproduction of the text of this lecture, or any extract from it, must credit Gresham College.

Part of:

This event was on Fri, 19 Jun 2009

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham College plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login