Law and Lawyers - Not All Bad? A Life in the Law - Not All Good?

Share

- Details

- Text

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

In his last lecture, Geoffrey Nice reviews what he has discussed over the last four years. Law should not be of that much concern, most of the time, to non-lawyers if it delivers what the public needs. So identifying what may interest and inform a Gresham audience is never easy for Gresham Law Professors. Geoffrey Nice reviews what he has learned often giving lectures about things he wanted to learn about that affirm how law should be the servant of man, never her mistress. He will bring some topics up to date explaining how particular views have developed and changed.

Download Text

04 May 2016

Law and Lawyers – not all bad?

A Life in the Law – not all good?

Professor Sir Geoffrey Nice QC

A summing up

To some extent bound by barrister rules – not too much personal opinion on controversial subjects, such as BREXIT

Thanks to Sir Thomas Gresham

Unreasonable demands made on – and immense thanks due to all Gresham College Staff under Academic Registrar Valerie Shrimplin, James Franklin, Dawn Fulks, Alex Mee, Richard Taverner, Tinko Georgiev and Georgina Calver.

Many thanks also go to Nena Tromp, Sarah Clarke, General Sir Nick Parker, Rodney Dixon QC, Haydee Dijkstal and Avi Shaim.

Israel Gaza lecture – the real loss

Actions of Provost and Academic Registrar – freedom of speech

Maintaining freedom of speech – part of what Gresham may have wanted by provision of lectures - had he only known

Different types of lawyers – those who are simply very professional; those who are highly intellectual and academic; and others too in addition to the merely sceptical, who may be wrong to be sceptical.

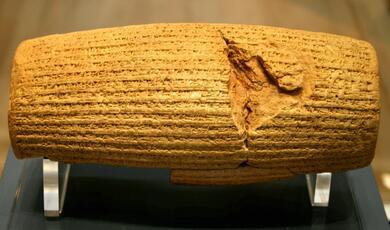

LAW: And for our country we see the law, and to some extent the lawyers as good things, bringing timely change. By statute law: against slavery, reforms of the franchise, abolition of capital punishment, abortion, Human Rights

Judge made law – Denning; R v R a man who had sex with his wife against will could, after 199 be guilty of guilty of rape when the Law Lords changed the law. Interestingly, many other European countries similarly changed their law on this point between 1980 and 2005.[1] The common Law approach to ‘making’ law in this particular case well explained by Lord Keith:

"……. The common law is, however, capable of evolving in the light of changing social, economic and cultural developments. ……. one of the most important changes is that marriage is in modern times regarded as a partnership of equals, and no longer one in which the wife must be the subservient chattel of the husband. Hale's proposition involves that by marriage a wife gives her irrevocable consent to sexual intercourse with her husband under all circumstances and irrespective of the state of her health or how she happens to be feeling at the time. In modern times any reasonable person must regard that conception as quite unacceptable."

New law is usually about change – take the same judge I referred to as a shocker in an earlier lecture who had made at a sentencing conference a joke about giving a rapist at a university a ‘half-blue’; 2 anecdotes.

Change looking back or looking forwards:

Hillsborough; a completely changed narrative. How many parts of the overall system bear responsibility? Just the police? May we – as Andy Burnham recently said – need to worry about the adversarial system itself that allowed unacceptable accounts to be peddled and pushed? Is a system of law that allowed this to be trusted even if it make a correction in the end?

The Jogee case, which involved the criminal law of joint enterprise in relation to murder, on which the courts had taken a wrong turn in 1984…….. the fact that the accomplice foresaw serious harm would be evidence from which a jury could conclude that he intended serious harm – and could therefore convict him of murder.[2]

One lawyer appearing in the case wrote for the London Review of Books:

This was the case until the Hong Kong appeal of Chan Wing-Siu came before the Privy Council in 1984. Here the law made its wrong turn. Sir Robin Cooke, a senior judge from New Zealand who was later given a peerage and sat as a judge in the House of Lords, laid down foresight of what the accomplice might intend to do as the test of criminal liability in joint enterprise cases: he did so because he had not grasped that although foresight may be evidence of intention, it had never previously been treated as a substitute for intention, and should not be confused with it. Nevertheless, in the long line of appeal cases that followed Chan Wing-Siu’s, and in countless trials, Cooke’s words were held as authority, and the doctrine took root. No one knows how many people have been found guilty under the Chan Wing-Siu rule who would not have been before Cooke changed the law.

During the October hearing, Lord Toulson pointedly asked the counsel for the prosecution (who was trying to defend the law as it then stood) what had changed so dramatically in society at the time of Chan Wing-Siu to warrant so great a change in the law; history, and the cases going back over the centuries, showed that people had not started committing offences in groups in 1984. The counsel found it difficult to answer. In its judgment the court declared that ‘there does not appear to have been any objective evidence that the law prior to Chan Wing-Siu failed to provide the public with adequate protection.’ With those words it knocked away the spurious public policy defence of the rule, which held that there was a pressing social need to treat group violence with a broad legal brush, and which has disfigured judicial thinking about joint enterprise for three decades.

Judges are masters of diplomatic language. Criticism tends to be muted, but is no less powerful for it. When a judge calls an argument ‘bold’ or ‘novel’, they really mean it’s barking mad. So when the Supreme Court bluntly says Chan Wing-Siu was an ‘error’ and ‘the correction of the error … brings the common law back into recognition of the difference between foresight and intent’, the gloves are off. Cooke screwed up, it means. The doctrine of precedent cemented the error into law, until now.

The change in the law on evidence of children and victim of sexual crimes.

Are you content that the law changes in the end? Or are you concerned that it was in disrepair for long?

And before you reckon the law is always to be trusted read passages in the Provost’s ‘The Third Reich in Power’; it will disturb your sleep.

ADVOCACY AND JUDGES the need for courage – in this and other professions

Another group of lawyers – radical lawyers

Radical lawyers pre-eminently radical in oral presentations at court – and to the necessary extent courageous – Cicero; Robin Simpson QC and the gaming licence

Lord Neuberger, senior Justice of the Supreme Court:

I remain a very strong supporter of oral argument …. oral discussion not infrequently has resulted in my reconsidering and even changing my mind – sometimes more than once ….. It is not entirely clear to me quite why oral argument is of such benefit, given that we so often have first class written arguments, but it clearly must be something to do with the way the mind works – the human mind, not just judicial mind.

[Advocates] Enjoy exclusive rights to represent litigants in court, they are accorded a status in society, and, at least in some fields of law, they have the opportunity to earn quite large sums of money. And there is a reason for this ….. the reason that independent advocates have privileges is because of the fundamental importance of having independent advocates in a modern civilised, democratic society – and above all a society run in accordance with the rule of law.

I am not criticising the legal profession for the high earnings which some of its members, albeit not a majority by any means, enjoy. If we are to have a first class legal profession, we need some of the most able young people to become practising lawyers, and it is naive to expect many able young people to become barristers if the financial rewards are paltry, although I must add, expressing my great admiration, that a few of the most able young people are socially committed enough to enter the less well paid areas of the law. But, human nature being what it is, the most sought after jobs at the bar (and elsewhere in the law) are inevitably at the higher paid end. ………. Ensuring that problems and cases are dealt with in a genuinely proportionate way, so that costs are commensurate with the amount or issues at stake is the ultimate aim, and it is one to which everyone, not least advocates, must strive.

Shortage of money ……. confronts the rule of law in general, and access to legal advice and representation, and hence the legal profession, in particular. And in the long run it could risk undermining public confidence in the rule of law. In some countries, such as the UK, this is a difficult issue in which to excite much interest, because, due to out fortunate history, we tend to take the rule of law for granted, and we blithely ignore threats of the break-down of the rule of law. The lesson for such countries is well summarised in the adages“the price of liberty, and in particular the price of the rule of law, is eternal vigilance”, and “all it takes for evil to triumph is for good people to do nothing”. In other words, the complacency engendered by decades of internal peace and democratic government, endangers the rule of law. In other countries, the rule of law is more obviously and directly under attack, and judges and independent advocates have to risk more than being disregarded or laughed at when they speak out to support the rule of law.[3]

Well, yes in part. But I might differ in certain respects. I find it impossible to regard the huge sums of money some lawyers earn as justifiable even in societies where wealth is diverging ever faster. For commercial cases the level of earnings by the merchants encourages – or even invites – very substantial payment to lawyers. I remain unreconstructed in several ways, one of them in finding talking about, or even thinking about money, slightly demeaning and remaining suspicious of any well-intentioned task being over rewarded. I am probably wrong in that.

For most of my professional life I earned comparatively little and in the last few years where rates have risen I have, I hope, moderated the total bill by application of a multiplier to the rate that always a substantial understatement and never the reverse. And, of course, much of the work I prefer to do is entirely without pay.

It is a difficulty of comprehension I have similar to the one I have for dodgy foreign potentates who prefer to die after decades of being presidents, here of there, with huge wealth corruptly harvested with the absolute certainty that their reputations will be openly trashed once dead – few reputations of the long serving presidents of Africa or elsewhere survive long and some leaders – Tony Blair and One of the Presidents Clinton – contrive a measure of reputational self-destruction in their own lifetimes. But then I cannot understand how a four story yacht is worth the stripping of a knighthood and public disgrace.

And so, for me, when my reputation was attacked by the Privy Council in the case of Michel I spoke about earlier – completely unjustly as events were to show – I had no doubt whatsoever that there was no alternative to finding the courage I needed not to jump from the bridge but to deal with these powerful people who knew me not at all. I explained a bit of what happened in one of my lectures and may in due course, put on my own foundation website the entire correspondence and the tape recordings that Lord Philips, Lord Brown (who relished crafting the destructive judgment, it seemed), Baroness Hale and Lord Neuberger authored. The correspondence draws to the attention of the Justices who were quite determined not to face me or to confront the evidence or the witness who so courageously put them right. I may have been caught up in a trial that was expected to bolster the image of an island always vulnerable to disdain when the extent of money washing its professional engaged in was revealed – as perhaps now more possible to see than then - and in which I may have been expected not challenge the received division of right (in all except those actually caught) from wrong.

Two things of interest now, one rather recent:

First, having been advised how my sitting in with the Jurats on the trial might allow me to push them in the right direction although the decision was supposedly theirs alone I made great and entirely successful efforts to construct a system for eliminating my influence altogether and leaving the decision making entirely to the process of argument by the advocates. No one on the island – apart from the advocate Kathy (Caitriona) Fogarty who had the courage to tell truth and display morality and ethics to the Privy Council – bothered to value that and this shows how whenever power holders are challenged, in this case the island’s establishment and its senior lawyers who could so easily have maintained that someone so determined to operate the system in this transparently clean way could not possibly be the villain abandoned me and would be happy never again to see me on their island, their interests must come first. Proper examination of what I did would have shown not only complete dedication to getting a right answer according to their system but could have improved the system.

Second, included in what I wrote to the PC In a letter to Philips written in August 2012 copied to all other Justices I observed:

“Maybe the senior appellate courts should sit with assessors - lay or legally qualified - who could bring more ordinary experience to bear during hearings although taking no part in the judgments. In this case it is hard to imagine a magistrate or a GP or a school teacher or a circuit judge sitting with the Board not asking why on earth the judge's position was not being protected. And they would probably have seen through the other features of the hearing and of the conduct of counsel that Ms Fogarty, I and many others have thought obvious and that should have put the Board on its guard (failure of counsel at trial to intervene; failure of counsel at trial to expose jersey's culture in full, counsel having a vested interest in disposing of a new Commissioner clearly willing to reflect his and the Jurats’ concerns about the island's culture, clear indication by me in summing up that Jurats could/should acquit Michel of the most substantial count facing him, etc). In criminal courts juries these days are confident enough to ask questions, even when discouraged by the judge in accordance with modern judicial training. Jury questions not infrequently pick up points of importance missed by counsel or ask questions revealing of truth that counsel, for tactical or strategic reasons, prefer not to ask. Any appellate court that allowed its proceedings to be democratised by the inclusion of a lay of junior judicial element might, to its surprise, find itself in a vanguard of procedural developments that would be adopted enthusiastically elsewhere.”

From my lecture on Regulation:

There seem to me several steps that could be taken to avoid my particular misfortune happening to others: First, just as Lord Sumption was recently promoted straight from the ranks of the Bar to the Supreme Court the Appointments Committee should encourage more applicants from barristers and solicitors of diverse backgrounds (Baroness Hale is the only woman on the Supreme Court that includes no one from an ethnic minority) especially those with more radical approaches to the law. The committee – at least the lay members of it - would probably be both astonished and delighted to find, say, a high street solicitor – especially if with a non-white non-Anglo Saxon background – having the qualifications to sit as Supreme Court judge bringing common sense and an entirely different perspective to the major legal issues of the day. Another way to secure some form of control on the over homogeneous bench might be to have lay assessors – not unlike jurors – sitting with them. Selection would be difficult and, of course, they would not be able to ask questions directly or to be involved in the writing of the legal judgment – but the lay view with an ability to prod the Justices into asking questions not asked by counsel could be invaluable for justice – after all, the people who have dared to challenge the establishment view and speak to me about the case concerning me have commented: Why weren’t you asked? Why weren’t the tapes listened to? Why wasn’t Miss Fogarty approached? Obvious enough to most lawyers, schoolteachers, university lecturers etc – but not to our legal leaders in chief.

Lord Neuberger

The relationship between the judges and professional lawyers, perhaps especially advocates, is therefore very important.

….we each have a system which ensures that the two groups, judges and lawyers, understand each other. A late-entry judiciary consisting mostly of people who have been practising lawyers is a great advantage. It means that our judges have experience and understanding of the other side of the courtroom, with all the pressures of legal practice, and it also means that our judges have some direct experience and understanding of the real world (if there is such a thing) outside the courtroom.

That is not to say that I am against recruiting judges from other areas, such as academia or government. On the contrary, I think that limiting judicial recruitment at any level to former practitioners is positively to be discouraged. Diversity is always an important aim, and it should not be limited to the familiar categories, such as ethnic origin and gender. Diversity in social, educational, and professional backgrounds is every bit as vital. Nor would I rule out any element of early-entry judicial career structure. Not only would it add to diversity of judicial background, but it may improve diversity by attracting those who might otherwise drift away from the world of law.

Two ICTY cases – something of an update and a contrast; or not?

Karadzic, judgment of 2016

In determining the appropriate sentence to be imposed on the Accused, the Chamber has had regard to the particular gravity of the crimes for which he is found responsible and the significant contribution he made to their commission. These are among the most egregious of crimes in international criminal law and include extermination as a crime against humanity and genocide.

In mitigation, the Accused presented evidence in relation to an agreement he claims to have entered with Richard Holbrooke in July 1996 whereby he resigned from public and party office and withdrew from public life with the understanding that he would not be prosecuted at the Tribunal. The Chamber considers that regardless of the reason or reasons behind his decision, the Accused’s decision to resign from public and party offices in July 1996, is a mitigating factor. The Chamber has also given regard to the Accused’s other arguments, such as his expressions of regret, his good conduct at the UNDU, and his personal circumstances.

Seselj a majority decision acquitting Seselj of all charges. The dissenting minority judge Lattanzi wrote:

“I note, for instance, that the majority refers to witnesses’ written statements and to their testimonies, without providing any explanation, even though these various pieces of evidence are often contradictory. I also note that the majority’s reasoning does not include the totality of the Prosecution evidence and knowingly focuses on the sparse Defence evidence on the record. This prompts the majority, for instance, to consider the forced displacement in buses of non-Serbs from their villages as a “humanitarian aid” operation, which is not a reasonable conclusion in light of the evidence on the record.

In addition, the majority very seldom mentions the applicable law, which is often contradicted by the reasoning followed by the Chamber; in the event that it does follow the applicable law, the Chamber adds standards that are not provided for in the Tribunal case- law.

We also have the requisite evidence to conclude that he incited the crimes charged in the Indictment (with the exception of plunder) through all of his inflammatory speeches, calling clearly and directly for the expulsion and forcible transfer of the non-Serbs, in addition to his speeches in which he denigrated and dehumanized the Croats comparing them to “primates” and “vampires” and qualifying them as cowards. In the same way, he called the Bosnian Muslims “balija” or “pogani” which he himself translated as “excrements”. I hold that the use of these terms, together with his constant references to “genocide” committed by the Croats during World War Two and the saying “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth” and “revenge is blind”, Vojislav Seselj also took the risk that murder, torture, cruel treatment and destruction would be committed in furtherance of the common criminal purpose he shared with the other leaders in the former Yugoslavia who participated in the JCE, the purpose of which was to force through the perpetration of crimes, the non-Serbs to leave the territories claimed by the Serb forces.

Under the pretext that the Prosecution did not do its job well – one can always do better, and the Trial Chamber could have also done better from the outset of this case, notwithstanding the difficulties it encountered during the trial – the majority sets aside all the rules of international humanitarian law that existed before the creation of the Tribunal and all the applicable law established since the inception of the Tribunal in order to acquit Vojislav Seselj.

On reading the majority’s Judgment, I felt I was thrown back in time to a period in human history, centuries ago, when one said – and it was the Romans who used to say this to justify their bloody conquests and murders of their political opponents in civil wars: “silent enim leges inter arma” - “In time of war the laws fall silent” (Cicero Oratio pro Milone, 52 B.C.).

How much are the interests of victims honoured by a court publicly this much in internal conflict? What will victims think of a court that after 10 years of trial reaches no conclusion of any coherence? The ICTY is a new court entitled to understanding but when justice processes are regarded as systems are there similarities between uncertainty of the kind shown here and the uncertainly 27 years of Hillsborough judicial processes visited on the victims of that tragedy? Must we be for ever alert to shortcoming of legal systems, rather as Neuberger explained?

In digging out material for these lectures I found, at an early stage, this passage from Charles Darwin’s ‘The Descent of Man’:

‘As man advances in civilisation, and small tribes are united into larger communities, the simplest reason would tell each individual that he ought to extend his social instincts and sympathies to all members of the same nation, though personally unknown to him. This point once reached, there is only an artificial barrier to prevent his sympathies extending to men of all nations and races’

Given an interest more in why people behave badly does this provide, in the first sentence, a non-religious reason for behaving well in self-interest?

Does the second sentence allow us to go a little further and justify a continuing approach to territorial neighbours, even across the English Channel. It certainly would be in contrast to, say, Nigel Farage saying:

‘Perhaps our own opposition to even the level of European integration we have now, let alone any more, is well known.’

Downe in Kent has provided homes to both Charles Darwin and Nigel Farage; the words of one of them will last a very long time.

As an inexcusable act of vanity I had the College of Heralds construct a coat of arms – of single generational use I fear as I have three daughters and coats of arms pass for use only through sons and heraldry may be last bastion of an old fashioned land.

When it came to the motto I was perplexed. But by looking back on where I had come from and decided on this aspiration:

'That I may place others' causes before my own'.

UT ALIENAS MEIS ANTEPONAM CAUSAS

Sir Thomas Gresham looked for guidance in his life to a divinity in the motto ‘Thy will be done’; in a secular age guidance for how lawyers may act by consideration of the interests of others could be seen as not inconsistent with Gresham’s view of personal responsibility.

© Professor Sir Geoffrey Nice QC, 2016

[1] https://www.supremecourt.uk/docs/speech-160303.pdf

[2] www.supremecourt.uk/docs/speech-160303.pdfthe

[3] https://www.supremecourt.uk/docs/speech-160416.pdf; https://www.supremecourt.uk/docs/speech-160421.pdf

Part of:

This event was on Wed, 04 May 2016

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham College plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login