‘Is it in Pevsner?’: A Short History of the ‘Buildings of …' Series

Share

- Details

- Text

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

This lecture traces the history of this famous series by Sir Nikolaus Pevsner, starting from its conception in 1947. It describes the research and writing of the original forty-six volumes for England and the extension of the books to Scotland, Wales and Ireland. It then assesses their significance alongside a reflection on the 2024 achievement of the full updating of the English series.

Download Text

Is it in Pevsner? A Short History of the Buildings of… series 1951-2024

Charles O’Brien, Series Editor, Pevsner Architectural Guides

05 December 2024

‘The hall was originally part of the London mansion of John Macworth, Dean of Lincoln who died in 1541. He left the property to the Dean and chapter and they leased it to Lionel Barnard, who in his turn allowed students of law to use it. The hall dates from the late C14. it's one remarkable and indeed very rare feature is the original octagonal Lantern or Louvre. Part of the roof with arched braces and hollow chamfered tie beams and collar beams is also original. The walls are a faced with yellow brick and have altered windows which are just one almost unbroken row of square headed lights. Early 16th century linenfold panelling with some renaissance motifs the buildings to the east and northwest are of yellow brick and seemed to be early 19th century’

Those are the words of Nikolaus Pevsner (1902-83) in his entry for Fetter Lane in the volume titled London: The Cities of London and Westminster, first published in 1957 describing the building in which I am speaking to you.

That book was one of a sequence that would eventually number forty-six volumes, covering the whole of England, county by county.

The first salvo came in 1951, when Penguin Books published three slim paperback guides to Cornwall, Middlesex and Nottinghamshire. 23 years later, the book for Staffordshire brought the cycle of works to a close and the question: Is it in Pevsner?’ was early to the lips of anyone interested in the buildings of England.

Revision and updating of the earliest works began even in Pevsner’s lifetime. This year, that programme has been brought full circle with completion, of full revisions of every book in the series, concluding as it happens with Staffordshire once more but now stretching to 56 volumes and no longer limited to England but extended to Wales, Scotland and Ireland.

Few can have imagined at the conception of the English series that it would be completed not once but twice and would stand out in the world as a unique and unrivalled companion to understanding and appreciation of British and Irish architecture both ancient and modern.

This evening’s lecture is about that Series but it is impossible to avoid beginning with the man:

Nikolaus Pevsner was born in Leipzig in 1902. He belongs therefore to that early 20th century generation whose lives his childhood and adult hood were cleaved by the First World War. In 1929 he was in possession of his first full teaching post at Gottingen University and this had occasioned his first visit to England in 1930 to source material for lectures on British Art and Architecture for an English Studies course, when he had been struck by what he perceived as the backwardness of much modern English architecture in comparison with the Continent and it might be said the inadequacy of for example the Baedeker guides which offered a guide for the visitor. Records of his trip attest to his omnivorous interest in gathering information allied to an astonishing work ethic.

Nevertheless it presented England as a plausible option when with the rise of Hitler, his Russian-Jewish ancestry ensured his removal from his post and led to his decision to leave Germany. So it was that he returned to England in 1934 initially on the temporary basis, lodging in Birmingham, and using the initial months here to collect research material to for what would become his study ‘Pioneers of the Modern Movement’, published by Faber & Faber in 1936 Alongside this he was granted a fellowship at Birmingham University to undertake an Enquiry into Industrial Art & Design commissioned by Philip Florence, Professor of Commerce, to analyse the role of the designer in industry (the findings of which were initially issued in a series of articles and then published in 1937). Between them these projects would keep Pevsner busy, if not well-remunerated.

The passage of the Nuremberg Race Laws it was clear that the prospect of returning home was closed and in 1936 he brought his family to London, having secured a home at 2 Wildwood Terrace in Hampstead, where he remained for the rest of his life and where in time the English Heritage Blue Plaque was erected to his memory in 2007.

What facilitated this opportunity to be reunited with his family and more secure financially was a job working as a buyer for the London shop of the furniture designer Gordon Russell of Broadway (a maker he praised in his Enquiry into Industrial Art in England and who would produce the desk that Pevsner and his successors took from office to office. Here they are thirty years later (a photo on display in the Gordon Russell Museum). He also tried his own hand at interior decoration working up a scheme (unrealised) for Gribloch House in Stirlingshire, a house of 1938-9 in a quasi-modern style by the young Basil Spence.

The prize of a full academic post in art history remained remote. As the 1930s progressed towards their by now well known dénouement, Pevsner continued to live a diverse life of employment. The critical moment came through his connections with the Architectural Review magazine, to which he had been committing articles in the mid-1930s and which at that time was the most progressive and wide-ranging of the architectural journals.

That brought him into contact with its assistant editor, Jim Richards whose Introduction to Modern Architecture had been published by Penguin Books in their Pelican series of non-fiction titles in 1937. At some point on the eve of the war, Richards made an introduction for Pevsner to Allen Lane, the suave and dynamic director of Penguin, who was looking for an author for a single-volume history of European Architecture,

This became another title in the Pelican Series: An Outline of European Architecture, which Pevsner partly prepared in unusual circumstances, while interned as an enemy alien in mid-1940 after the fall of France. He and others were sent to the half-built housing estate at Huyton on the edge of Liverpool.

Pevsner ultimately obtained his release back to London in 1941 and began firewatching during night raids at Birkbeck College, which stayed open through the war and where he was also engaged as a part-time lecturer. At that time in Bream’s Buildings very close to where I am speaking to you now, between Chancery Lane and Fetter Lane; a C19 building that was hit by a bomb in 1944.

This Blitz experience simultaneously sharpened public interest in the possibilities of replanning after the war through exhibitions and publications (for example Ralph Tubbs, Living in Cities, 1942)

It was in this period that Pevsner now took over as assistant editor at the AR and to which he now contributed a series of articles called ‘Treasure Hunts’ (published together in 1942).

This was as Anne Hultzsch has described it ‘architectural history from eye-level’ and invited the reader to ‘date your district’ by observation of small details, the elevations about shopfronts and so forth and relate them to a wide architectural history – showing at this early date Pevsner’s interest in communicating to an interested by lay audience and stressing the importance of visual appreciation. This approach chimed very well with initiatives in the years after the war such as ‘Picture Penguins’ that laid similar emphasis e.g. the ‘Things We See’ series Houses by Lionel Brett (1947) and in this we can seen the beginnings of what would make Pevsner a household name.

In 1945 now well-established as Lane’s captive expert on architecture NP was invited to Allen’s house at Stanwell, Middlesex, west of London, to offer suggestions for a new series of books.

Pevsner had two proposals: one was for a multi-volume scholarly history of art and architecture, which became the Pelican History of Art, the other was for a series of guidebooks to English architecture, inspired by the Dehio handbuch available to German travellers from 1900 onwards. It was an idea which Pevsner had tried out without success on other publishers before the war but postwar was able to fit in with the revival of curiosity about England that was again becoming accessible for the enquiring traveller once petrol coupons were abolished.

The mission would be defined as covering ‘all ecclesiastical, public and domestic buildings of interest’ -a suitably elastic criteria which has proved extraordinarily helpful over time.

Work began in 1947. Penguin provided Pevsner with an office and a secretary. The offices were in a succession of buildings in Bloomsbury, mostly in Gower Street, a thoroughfare famously written off by Ruskin as the ‘nec plus ultra of ugliness’ but which Pevsner would quote in his second volume for suburban London as ‘xxxxx’. The office was convenient for the Reading Room at the British Museum Library and in time also for Birkbeck College which had relocated to Malet Street by the University of London campus in 1952. In the early days, NP employed two German secretaries to prepare his research notes, probably fellow refugees deprived of their academic careers, and subsequently a succession of students including John Harris who wrote pungently but amusingly about his distaste for the work.

Mostly the information in the beginning was drawn from published surveys of buildings. There were the scholarly inventories produced by the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments; the detailed parish histories of the Victoria History of the Counties of England and in the capital there was the Survey of London, founded by C. R. Ashbee in the last years of the C19. All had been begun around 1900 but none were complete, nor comprehensive, nor easily portable.

Then there were the popular tourist guides such as Shell guides, which began in 1934, or the even older antiquarian county histories with varied coverage of architecture or Murray’s Handbooks (reissued without success postwar). These concentrated on the antiquarian or the picturesque, with much emphasis on biographical or anecdotal details.

This was not something Pevsner emulated in the first guide to be published: to Cornwall but the books were given a recognisable house style early on. Small portable format paperbacks and later hard backs from the mid 60s. Berthold Wolpe roundels drew a detail or vignette from the county to serve as a leitmotif and in the case of the London volume, one of the newest buildings in England: the Royal Festival Hall.

Pevsner's Outline of European Architecture, his articles for the AR and his general lectures at Cambridge and London had shown that he was no narrow specialist; the continuing success of the B of E vols surely owed much to his interest in a broad spectrum of buildings. Unlike the older established surveys with arbitrary cut off dates, Pevsner’s aim was to cover all periods of architecture up to the present day and explain their interest to his readers in books of a portable size. So in Middlesex he could grapple with the high and low of ‘modern’ Underground stations as well as major items like Chiswick villa., while Nottinghamshire played to his deeper architectural historical knowledge in the major churches at Southwell Minster returning to the subject of an earlier study on the leaves of Southwell the naturalistic carving in the chapter house of the minster.

How was it done? Armed with fat folders of notes Pevsner set off to visit two counties a year in the Easter and Summer university vacations, to result in two publications a year. Here he is at Wimborne in Dorset, early 1960s.

The dress and the equipment are characteristic: the board upon which he secured A5 or even quartered sheets of A4 lined pieces of paper to make his notes and (as here) occasional sketches; this is material on Chichester Cathedral and prepared for the Sussex volume. The illegibility was notable.

This dedication would be impressive enough had this been Pevsner’s only activity but the prewar and wartime investments in seeking work were now paying off, possibly too handsomely, in the form of the Slade Professorship at Cambridge from 1949 and the ongoing work for Birkbeck as well as wider celebrity through a growing profile on radio culminating in the Reith Lectures of 1955 on the ‘Englishness of English Art’ – a theme going right back to that initial visit to this country in 1930 and his interest in what set this counrty’s architecture apart from while within the European scene. All this had to be accommodated to the annual tours and the balance became acute with the turn to the 1960s by which time the growing reputation of the series recommended him as a figure on professional bodies.

Initially Pevsner was driven by his wife Lola, until her unexpected death in 1963 (she was credited in the foreword to Northamptonshire as performing ‘like an overworked taxi chauffeur without limited working hours or free Sundays’) but also in a later memoir as the source of some of the keenest observations of detail in the books. Subsequently other assistants, mostly students, took over notably John Newman, then studying at the Courtauld, and with whom Pevsner shared duties in the writing of the Dorset volume before handing over the entire job of the Kent vols to John’s hands MOVE JOHN’S PICTURE HERE. In practical terms it would have been impossible to cover the ground without a companion, to ensure that Pevsner could state “I have myself seen everything that I describe with a few exceptions”. Susie Harries biography of Pevsner, published in 2011, captures the experiences of several of these young drivers in vivid form.

It was a punishing schedule and he would write ‘The journeys are just not human. To bed 11.0, 11.30. too tired even to read the paper. Up this morning at 6 to scribble, scribble, scribble. If only one could be proud of the result’. So many and various were the hotels and pubs that they stayed in by 1958 (12 volumes in) NP was writing to The Observer to advise on the proper but economical furnishing of a hotel room. It explains the dedication in the North Riding volume of 1966 to ‘Those Publicans and Hoteliers of England who provided me with a table in my bedroom to scribble on.’

As soon as travelling was finished Pevsner shut himself away to write the introduction. Cornwall back in 1951 was dealt with a mere 15 pages; by the later books these were developing into 20-50 page essays on the development of architecture in each county, written by a scholar up to date with the latest international research. This was another feature which set the series on a different level from previous guide books.

Compared with the Shell Guides the resulting Buildings of England volumes were terse and uncompromisingly serious. Places were arranged in A-Z order; within them entries on significant buildings were organised under churches, public buildings, and for larger places ‘perambulations’ a more free flowing summary of other buildings of interest in the streets of a town or city, which a rather curious term has probably surviced much longer in the English lexicon if he had not adopted it. These were in some ways the descendant of those Treasure Hunts, pioneered in the AR.

Much attention was given to the design of a compact but clearly laid out text, which was conceived by Hans Schmoller, Penguin's outstanding chief typographer. Current volumes still follow his main conventions; for example starting a paragraph in the margin to denote a new subject, the use of small capitals within the text, and the use of italic for architects' names.

There were illustrations, gathered together and arranged in chronological order of subject matter; although not very well printed and drawn mostly from the available photos in the National Monuments Record (now part of the HE Archive) with a smattering of better photos from Country Life. A glossary guided the reader through the more technical terms.

The limitations as well as the positives of any multi-volume work produced by a single author will be obvious. The strict selectivity of the earlier volumes was inspired by a concept of what one might term the progress of ‘mainstream art history’ and left little room of obvious understanding of such matters as the vernacular architecture of many counties or local building materials, deficiencies improved in time by contributions by experts on timber-framing and contributors like Alec Clifton-Taylor.

From 1960 the challenges of seeing the job through in timely fashion were acute and collaboration seemed inevitably. The first was Ian Nairn (in Surrey), followed by John Harris (Lincs); David Lloyd (Hampshire), Sandra Wedgewood in Warwickshire and Jennifer Sherwood (Oxon). Handing over the reins completely was rare: David Verey in Glos and John Newman in Kent; JOHN having started as one of the drivers (for Berkshire) in the early 60s. Each brought something of their own interests and knowledge in country houses and estates, townscape, and so on, so what could have been formulaic became nuanced and often unexpected.

Wider changes also benefited the books as they appeared. On the one hand there was compilation of the Lists of buildings of Special Interest prepared by Govt in the first of a series of systematic surveys from 1953 under the aegis of the Historic Buildings Council to identify buildings meriting protection. Pevsner would join an august subcommittee of the council in 1959 to consider the question of listing Victorian buildings (which was permissible but rarely acted upon, the presumption up til then having been firmly in favour of pre1800 architecture)

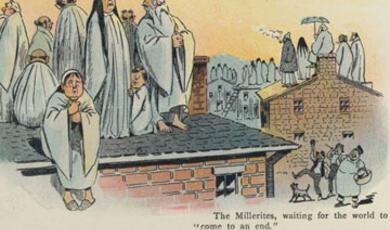

Pevsner’s interest in the Victorian went back to the beginning of his career and was sharpened in the more threatening environment of the 1960s, bringing him into the arena of the new Victorian Society. This cartoon by Tom Greeves shows an early Society outing with Pevsner in gown and mortarboard, the professional architectural historian and the more twinkling figure of John Betjeman alongside.

This was but one aspect of the general growth of interest in many aspects of architectural history which made so many more buildings eligible for inclusion in the guidesas they appeared and Pevsner’ s interests and approach, also evolved as the series developed, as research became more thorough and as he became more confident of his audience.

So the BofE developed a new role over the course of the first editions of becoming a tool for conservationists and planners – strengthened by the emphasis under the Labour Government of 1964 and 66 in promoting the use of Conservation Areas (capturing precisely those ensembles such as planned surbirban districts which the ‘perambulations’ in the guides might have singled out for attention.

The first editions of the guides to the predominantly Victorian industrial areas such as Birmingham, Liverpool and Manchester and the Black Country (Warks 1966, Lancs 1969. Staffs 1974) were generally weak on the importance of the country’s industrial heritage but again in time would benefit from greater understanding and a wish to promote reuse.

As a member of the Historic Buildings Committee Pevsner was also involved in the first proposals for the listing of 20th century buildings up to 1939, a subject that certainly set the series apart in showing an interest in it. His initial list of 50 buildings meriting protection would take until after 1970 to be eligiblke for listing.

Initially this meant the Thirties - and a particular conception of the principal strain of architecture which was of interest - but as time wore on more of the new architecture of the postwar period mertited attention,

Selectivity was always essential in the guides and remains so. It was governed by Pevsner’s own view of what he considered the appropriate style for the C20. It admired the style of the RFH but it did not embrace the American-inspired ‘jazzy cinemas’ of the 1920s nor the continuation of the classical tradition, either for country houses or for public institutions, which he considered inappropriate for C20 needs. By the last volumes of the late 1960s he recognised that his own preferred tradition of reticent international modernism was on the wane. He found the History Faculty Building at Cambridge by James Stirling of 1963-8, ‘actively ugly’ ‘rude’ and ‘anti-architecture’. This was a building which declared very clearly a new approach among modernist architects which emphasised the personal expression of the architect, regardless of context, and Pevsner did not feel in sympathy with its aggressive character.

The ability to say so is important – the books contained and still contain opinions and value judgements – you need not agree but they add spice to the necessary straight passages of description and made some entries memorable. Pevsner’s style and syntax had already caught the attention of writers such as Colin MacInnes and it must be said that some seemed to revel in being given bad marks by Pevsner – I notice the number of church guides which seemed to take pleasure in the dismissive remark.

PART TWO

‘PEVSNER SINCE PEVSNER’

Pevsner believed passionately in what he was trying to achieve but he was modest in his claims for the books, inviting readers to contribute corrections, and accepting that further research would often require his entries to be rewritten in the future.

So even before his work was complete in 1974, revisions of his work had begun. These early revisions like Cornwall (by Enid Radcliffe, 1970) were necessarily superficial, restricted to what could be corrected from information supplied to the office and almost exclusively conducted without the benefit of revisiting.

As the 1970s progressed more was possible, led by a new generation of editors at Penguin, themselves graduates in architectural history …. Bridget Cherry and Elizabeth Williamson

By the time he had completed the series Pevsner was 73. Already however plans were in hand for similar surveys, to be carried out by other writers, for Wales, Scotland and Ireland. From the early 1980s, the adoption of a new, larger format allowed for more extensive expansion, accommodating those fields of interest and research to which I referred a moment ago. In England this great programme of revision got off the ground in London (with London 2: South) by Bridget published shortly before Pevsner’s death and Leicestershire & Rutland by Elizabeth (1984).

Meanwhile inspiring the equivalent series for the United States

Upheavals within the publishing industry presented new challenges to the continuation. The costs of research and writing was increasingly unpopular with Penguin and Trusts were created in the early 1990s in Scotland and for England and Wales and latterly Ireland to pay for the travel and illustrations etc and to ensure the presence of two full-time in house author editors (initially BC and EW) joined from 1994 by Simon Bradley to begin the major task of revising the City of London and Westminster volumes and myself from 1997).

The London volumes (from 2 to 6 eventually, covering the whole of Greater London, in the process eradicating the Middlesex volume) were retained as ‘in-house’ projects with other authors signing on to revise the county volumes as people and funds allowed.

The objectives remained as they had always been, to provide a short clear and academically reliable survey of each county’s buildings, up to date with the latest research and interested in the contemporary scene.

Much of Pevsner could be retained in the county volumes and the typical village but by the 1990s the changes in many places since his day left little to work with, something thrown into stark relief by what was now underway in London Docklands. This nevertheless allowed for diversification of format to be explored, and the first paperback in the series since the 1950s (1998) by Elizabeth Williamson, exploiting an opportunity to secure funding from the LD Dev Corporation to foreground an area experiencing some of the fastest rates of new development and an area for which Pevsner’s descriptions from the old outer London volume were now well over forty years old. It all seems a bit quaint now!

We continued to be published by Penguin, moving around a variety of offices in London and latterly at Shell Mex House in the Strand until the 50th anniversary of the series when Bridget Cherry retired and the series was taken over by Yale University Press, based in Pevsner’s historic home: Bedford Square, Bloomsbury round the corner from NP’s Gower St office. With us – along with Pevsner’s table - travelled box files full of reader’s letters’ articles, cuttings and other ephemera waiting to be deployed on one of the revisions. As our output increased our employers found it easier to move us into smaller and smaller rooms!

As a major publisher of art history, Yale gave an enormous national and international boost to the profile of the books along with a smartening up of the presentation through the rejacketing of the by then multi-varied small and larger format volumes in then English series and in particular the move to colour photography, mostly supplied by the English Heritage photographers – whose artistry has stood out over the years and it was Sir Howard Colvin who confirmed that even some of the most distinguished members of the architectural history profession would go straight for the photos to see what the Pevsners deemed the most important 100 or so buildings of a county.

The renewed sense of purpose was consolidated by the innovation of the City Guides, part of a Heritage Lottery Fund supported initiative which began with Manchester and was followed by books on the major English cities, designed to maintain Pevsner's ideal of the books as an educational tool for a wide public.

In the same spirit would follow a new series of ‘Introductions’ volumes on specific building types.

The expanded and consistent output of up to four volumes a year helped to maintain the reputation and recognition of the series in the wider culture, gratifyingly acknowledged in seminars and conferences and awards but also the number of times that references to ‘Pevsner’ found their way into fiction and also into cartoons, showing that by now, two decades since his death, it was the books as much as the man which had entered the public conscious.

Each volume took time. Pevsner had a holiday to do it, his successors have taken about 3 years over each one (rarely full time). The methodology of the work, despite the impact over time of the internet and electronic research would have remained surprisingly recognisable to Pevsner; days of visiting, cold-calling at houses; writing up at the end of the day, finally the introduction. The books were longer, more detailed, more informed - precisely in the way that the early efforts had been criticised by now making time for research in archives so that many items in the newer guides are genuine discoveries and greater time on the ground to investigate - but the mission was still the same, to see everything described. At the end one is left with a very large quantity of paper, which goes to the Historic England Archive to join Pevsner’s own notes all of which can be consulted by the public.

From 2000 we produced the lion’s share of the full revisions for England, which put great pressure on a small but devoted team at the publisher of the two editors also trying to keep up their own revisions while supervising the work of a growing band of authors not only in England but in Wales, Scotland with their new titles appearing in a regular stream until complete in the first decades of this century.

Critical to keeping the show on the road was finance. This is a private enterprise and (in the best sense) unacademic – NO FOOTNOTES!. Many of the revising authors were working for modest if any reward, largely driven by a passion and commitment to the series and the need. Yale provided the production support and the Buildings Books Trust the research support, but from 2012 the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art put a huge grant behind the programme. For the first time since Pevsner’s own day this gave us certainty and the ability to plan for the revision of all of the remaining volumes with multiple authors engaged and removed the problem that some counties are unlikely to draw funding from within the locality.

Meanwhile we have kept up our presence on social media.

Finally we have come full circle. The launch earlier this year of the revised Staffordshire, with which Pevsner completed his run (here seen walking away from his last church) was one of mixed emotion; immense pride in the achievement of a large family of authors over several decades (some of whom assembled to mark this event in the summer of this year) tinged with sadness that for now, with the disbanding of the editorial team after an unbroken succession over 75 years, the prospect of new editions for England, Wales and Scotland has vanished – this was not to be the Forth Bridge exercise that many hoped for. More positively the project to cover the Buildings of Ireland continues with three volumes in progress and we hope will be complete before too long.

Meanwhile, exploration is being made of the possibilities for a full digitisation of the gazetteers of the books so that the content can be assembled in the way that users want, updated and we can continue to fulfil Pevsner’s aim of providing a portable guide to all buildings of significance from the far past to the present day. So we can continue to ask: ‘What does Pevsner say?’

For many years I kept a cutting above my desk from an editorial in the Guardian in 2007. I do not know its author, but it read “As the British landscape has evolved, so have Pevsner’s guides – to read a Pevsner guide is to discover familiar places in a newly informed light, human history in all its beauty and confusion’. There is much beauty and much confusion in this world and so I close with a card, drawn by Julian Orbach, author and co-author of several volumes in the Welsh and English series one of a number to arrive in our office at this time of year, and wish you a merry Christmas.

© Charles O’Brien, 2024

This event was on Thu, 05 Dec 2024

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham College plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login