15 June 2011

Why Should We Protect Endangered Languages?

Nicholas Ostler

nicholas@ostler.net

Author of Empires of the Word, Ad Infinitum and The Last Lingua Franca

Chair, Foundation for Endangered Languages (www.ogmios.org)

According to our Manifesto

The Foundation for Endangered Languages exists to support, enable and assist the documentation, protection and promotion of endangered languages.

Some thought went into this formulation. It shows that our concerns extend to the past, present and future of endangered languages.

Documentation is the attempt to fix a language’s substance, what may be called its corpus, in order that it will never be lost to memory: this makes it available for scientific study in perpetuity, as well as (potentially) providing a basis for re-building competence in the language, should there be a new access of enthusiasm for it after natural transmission of the language has ceased. I am sure you will be well informed about the issues that arise in documentation by my learned successors today –Mark Turin and Peter Austin.

Promotion concerns attempts to raise the profile of a language, whether to non-speakers through the world’s information media, or – probably more importantly – to its own speakers and potential speakers through surveys and projects within communities, and also concrete efforts at language re-vitalization, if the natural transmission of a language is endangered or impaired. This is about the long-term future of a language, even if it can only be built up one generation at a time.

Protection, however, is what I shall be talking about. This is very much about the present of a language: is it to be sheltered from forces which would threaten its future? In the extreme case, might its use be abolished, and if not why not? This is likely to concern politics within the community, and also the surrounding communities or state, whose needs may be put before its own continuation.

I shall not be talking about the tactics and strategy of language protection, however. Rather, I stick to my brief, and answer the question: “Why Should We Protect Endnangered Languages?” The issue is an ethical one, and that is how I shall approach it.

Thinking of ethics brings up considerations of moral philosophy. Evidently, priorities differ here, and it is difficult to find firm ground on which to base an argument, especially when different parties have different interests, and different preconceptions. Immanel Kant attempted to get round this, by deriving some ethivcal content from the very concept of an ethical issue. If his argument goes through, it should transcend particular arguments for particular interests. Within his concept of the Categorical Imperative, he finds the content:

"Act only according to that maxim whereby you can, at the same time, will that it should become a universal law.”

Furthermore, he holds it intrinsic to an ethical agent that he or she should

“… treat others as ends in themselves and not as means to an end.”

These sentiments sit very naturally with the world-view that sees the protection of endangered languages as worthwhile, indeed an important priority.

It is eminently possible that all languages should be protected, hence the value of language protection can easily be made into a universal, moral law. Languages are often presumed (by the monolingual) to be involved in a kind of land war for people’s minds, so that – for example – if I speak English I must renounce Welsh, or Gaelic, or Jersey French – or indeed Navajo in Arizona or Pitjantjatjara in Northern Territory Australia (since English these last three or four centuries has been projected into contact with languages in every continent of the world). But, if the traditional, local, soon-to-be minority language is still respected (and indeed treasured), there is no reason why the acquisition of other languages should make it unfit for use, or unlearnable.

Furthermore, the idea of others as ends in themselves leads toward a valuing of others’ subjective experience of their own language, and away from the sense that languages should seen as means of communicating with others at one’s own convenience. As the slogan of the Hans Rausing Endangered Language Programme puts it, “every last word is another lost world”: languages are the basis for distinctive world-views, and certainly distinctly world-experiences, within a particular language community.

Contrast this with a tough-minded view of life as, in the immediate term, a zero-sum game: within this, some people’s gain (in reducing communication and transaction costs) has to be paid for by your loss, even if (in the last analysis) we all move to a higher – almost communist! – level where all can share the the information fruits which are on the table. On the way to this paradise of monolinguality, we have to accept a transitional period of dog-eat-dog, or what ancient Indian sages termed matsya-nyāya ( ‘fish-logic’ in Sanskrit), where the smaller ones are eaten by the bigger ones, all the way up.

I have already suggested that this view of language competition is flawed. It may have a certain sense of the dynamics of international power politics and global business, but it is clearly undesirable within any particular society, where considerations of equity and universal welfare have an indisputable place, and are indeed backed up by legal precept. Instead, let us consider an ethico-legal framework which values good-neighbourliness where others’ rights are to be respected – and indeed protected. It is the duty of the landlord (enforceable at law) to allow undisturbed enjoyment of his premises to the tenant. The law also respects the maxim

SIC VTERE TVO VT ALIENVM NON LAEDAS

So use your own that you do not hurt what belongs to another.

In practice, members of an endangered speech community don’t (all) want to speak their language less (even if some of them – notoriously – may[1]). It is often dear to them, and they are distressed at the thought that they will lose contact with their past traditions – and indeed older members of their own community, whether or not that community can continue through the medium of a new, outsiders’ language.

Nevertheless, they may be constrained, or bullied, or urged, or cajoled to do so, in order to fulfil some greater goal, either for themselves individually, or for the wider community. They are promised that, by abandoning use of their traditional tongue, they can be part of a greater empire (or nowadays, more likely, of a greater economy, in which they stand to be richer). They are urged ‘not to stand in the way of progress’.[2] Governments themselves will be reluctant to permit or support the continued variety of languages in their realm. Greater diversity is likely, at least, to increase the administrative cost of welfare. Traditionally, too, the different communities which are created by distinct languages have been a source of division within a state: how much simpler to encourage all citizens to content themselves with a national language, or at least one of a number of majority tongues.

In essence, the speakers of the endangered languages are being asked to pay the full price to accommodate a major change, and to build a new relationship between themselves and the authorities, but also among themselves as a community.

But an intellectual insult is added to this injury: to justify this added responsibility for the language-speakers, the reasoning which is adduced is often bogus, or based on false premisses.

Will the speakers, after all, have equal access to the empire or economy? Experience suggests that they don’t; so that for at least one generation, and probably more, they continue to suffer adverse discrimination. The discrimination which had been attached to their language is then converted to a slur on their poverty, their lack of education, their religion, or their personal appearance. And whose ‘progress’ is being promoted? When society becomes more linguistically integrated, the greater gainers – perhaps the only gainers – may be the existing elite who now have a bigger game of domination to play. The future may even have been misunderstood, and the plans go nowhere. Maybe the minority community holds some of the answers. Is there only one path to a desirable future? Certainly, an autonomous community with its own language may gain little when it comes to dependence on welfare support.

In fact, political ‘divisions’ – although potentially an embarrassment for a national government – are very likely essential to the future identity of a community. A surviving minority language is a convenient way of marking and defending this, and tying it up with a massive cultural tradition. Its loss leads simply to oblivion.

The loss of a language community does not, in itself, give other gains, even if it is seen as part of a process which leads to (beneficial) higher level integration: all the gains from that integration, however, are compatible with retention of a language (and hence the distinct identity of the community which speaks it). The only clear gainers from the loss are administrators, who may admittedly have an easier task when their communications no longer have to be bilingual or multilingual.

Even if it undercuts language discrimination in the long run, loss of a minority language doesn’t prevent discrimination as such (e.g. by accent, lineage, district, colour or any other useful attribute). By definition, loss of variety in a state or a society must impoverish it culturally – even if some such impoverishments have actively been sought by governments, occasionally, one may feel with good reason.[3]

What can be asserted with good reason is that loss of a minority language reliably finishes off a cultural identity and the cultural goods that have come with it. This can be seen in a variety of historical examples.

In what follows, I very briefly review the cases of three losers; the Gauls in the Roman Empire (1st-5th AD); Tupi-speaking Indians in Brazil (16th-18th centuries AD); and the Ubykh in Tsarist Russia (19th-20th AD). I contrast these with three (sometime) winners, despite apparently adverse conditions: the Basques on the Atlantic coast of Europe; Syriac-speaking Christians in Asia; and Pipil-speakers in Central America.

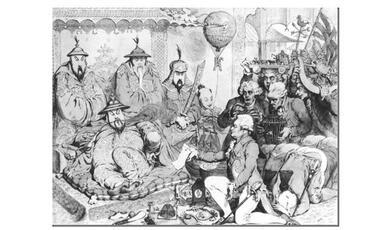

The Conquest of Gaul effected by Julius Caesar over Vercingetorix in 49 BC led – after some three centuries of linguistic change-over, presumably spreading from the cities and villas to the countryside – to the extinction of the Gaulish language (which had previously dominated northern Europe). We know from external testimony (such as Caesar’s own) that the Gauls’ spiritual leaders, the Druids, underwent a lengthy training which lasted about 20 years, and had the crucial weakness that it was all passed on orally and through memory. Nothing of it remains, except what can be deduced from the fragments of a single Druidical calendar which was inscribed on copper, discovered at Coligny. But we can see something of the complexity that was lost by looking at the Gundestrup cauldron, an art work found in Denmark (once part of the Gaulish-speaking area) which evidently illustrates the myth of the antler-horned god Cernunnos. There were clearly incidents with stags, snakes, other beasts, and also dolphin-riding. Since – as usual – no-one thought it worthwhile to translate and record into other literate languages the material that was distinctive to a language that was fast losing its transmission to rising generations, these stories, and their meaning, have all been lost.[4]

Gaulish is not alone among the lost languages of Europe. In the five centuries from 100 BC to 400 AD, known languages in lands under Roman administration fell from 60 to 12, and outside Africa and the Greek-dominant east, from 30 to just 5: these were Latin, Welsh, Basque, Albanian and Gaulish. By this time Gaulish, which had previously been the most widespread language in northern Europe, was already marginal, and doomed. The names of the lost languages, as far as we know them, toll out a sad litany crossing south Europe from west to east:- Lusitanian, Celtiberian, Tartessian, Iberian, Ligurian, Lepontic, Rhaetic, Venetic, Etruscan, Picene, Oscan, Messapian, Sicel, Sardinian, Dacian, Getic, Paeonian.

A millennium later, Tupi-speaking Indians in Brazil were soon encountered by explorers, as the Portuguese gradually established themselves along the coasts, often against direct competition from the French. The Tupi tribes were not noted for their peaceable ways, being confirmed cannibals, sustaining mutual eating relations with neighbouring tribes down the Atlantic coast. Nevertheless the Portuguese were able to subdue some of them, and settled them in reduções, ‘reductions’, where sedentary societies were set up under ecclesiastical control, notably under the Jesuits. The cannibalism was eliminated, and a sustainable Christianized modus vivendi was achieved (monolingually in Tupi), which lasted for over two centuries.

However, it proved vulnerable to political developments, not in Brazil itself, but in metropolitan Portugal. The Jesuit regime proved vulnerable to a two-pronged attack, from the growing Enlightenment in Europe which increasingly rejected Catholic authority (and hence temporal power for the Jesuits), and from commercial intolerance of these self-contained economic units maintained by them. Curiously, the first attack came as a prohibition against the Tupi language itself, which had always been the lingua franca in the Jesuit domains. In 1757, a Provisão Real (royal decree) was passed against any further use of the language. This was followed by a direct royal interdict two years later, which completely suppressed the Jesuit order in all parts of the Portuguese empire. The Jesuits withdrew without a struggle, and from that time the Tupi language declined as Portuguese language progressively took over, creating the linguistic situation seen in Brazil today. With the Tupi language (which survives today only in a small pocket in the north-western corner of the country), went any separate identity for the Tupi indigenes: although there had been widespread mixed marriages of Portuguese and Tupi over those two centuries, the use of Tupi had kept the sense of a cultural identity live over that period.

Thirdly, and most recently, we can instance the Russian conquest of the Caucasus, which actually took place over a full century, 1763–1864. At the end of this period, the Russians finally defeated the Ubykh people, a Circassian tribe, and expelled them from the north-eastern corner of the Black Sea littoral. They ended up, like many expelled at this time, in the territory of the Ottoman empire: the Ubykh settled on the coast of Marmara, not far from Istanbul. There they made a deliberate decision not to continue speaking their language, but rather to attempt to fit in with the local (Turkish-speaking) population.

There were, of course, a few families who did not comply, at least at first. And Tevfik Esenç, who was to end up as the last speaker of Ubykh, had been brought up largely by his grandparents, and so acquired the language a generation after his parents’ and their contemporaries had largely lost it. He was of a scholarly disposition, able to describe vast tracts of their traditional culture, including the romantic Nart sagas, to the French linguist Georges Dumézil; but he died in 1992, and with him went the life of the Ubykh way.

These have all been been negative examples, showing what is lost when a language goes, and by implication, why anyone should be concerned to protect a language that seems to be endangered. On the positive side, it is possible to cite languages which have survived in use despite terrible odds against them. These would naturally include the Basque language spoken, as it has been for at least 2,500 years, on the Biscayan coast of France and Spain - which still occupies much the same territory today, despite the varying overloardhips in Spain of Carthaginians, Romans, Goths, Arabs and Castilians; the Syriac language, co-eval with the Christian Churches of the east which still survive in Iraq and Palestine, but which in their time (a long time ago) once spread as far as Kerala in the south, and Mongolia and Beijing to the east. In a very different context again, the Pipil – a community of Nahuatl speakers of the south (in modern El Salvador) – have retained a distinct identity along with their language since long before the Spanish conquest of Central America, though once surrounded by speakers of Xinca, Lenca and Mayan Cholti, and now by speakers of Spanish..

So, in a nutshell, the answer to the question, ‘Why Should We Protect Endangered Languages?’, is that, if we don’t, the communities that speak those languages will vanish, (along with features that make their life distinctive), almost as if they had never been. This is a loss of something valued by its speakers, and hence valuable. And in the general case, there is no corresponding automatic gain. In the general case, such a loss is to be avoided, if at all possible. This is because it makes the world a poorer place, certainly; but above all it is to be be avoided for the sake of the speakers, who stand to lose – in the long term – their very identities, their treasured sense of who they are and where they come from.

----

[1] Peter Ladefoged, a phonetician with a good record in recording endangered languages, once remarked that he was not entitled to query the judgement of speakers of Dahalo, in choosing not to pass their language on to the next generation. Dahalo is a rapidly dying Cushitic language of east Africa.

[2] So for example, the last generation of Chinese in Singapore were urged by the Lee Kwan Yew government, to use only English, as being the language of world business. They complied, but with the current rise of the People’s Republic of China in the global economy, this abandonment of their own tradition is beginning already to look like a short-sighted choice.

[3] Consider the 19th-century abolition of satī (widow burning) or thagī (sacred wayside robbery and murder) in British India, or widespread cannibalism among the Tupi population of Brazil before its 16th-century take-over by the Portuguese.

[4] An important exception to this failure to transmit Gaulish culture comes in a vignette by the Greek essayist Lucian, who describes, in his Herakles, a picture of the Gaulish god of eloquence Ogmios, strong as the Greco-Roman demigod Hercules but able to draw his followers by the amber strings of his eloquence.

C - Nicholas Ostler, 2011

Login

Login