The Size of a Walnut: Your Heart in Their Hands

Share

- Details

- Text

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

What does it feel like to hold a baby's heart in your hands? To 'feel' their life. No one really talks about this, but as well as the obvious responsibility associated with cardiac surgery on children, there is also (for almost all surgeons) a great deal of emotion.

In an attempt to explain that to you, this lecture compiles a series of video interviews with paediatric cardiac surgeons around the world who explain how that physical contact with someone else's beating heart makes them feel.

Download Text

25 May 2016

The Size of a Walnut:

Your Heart in their Hands

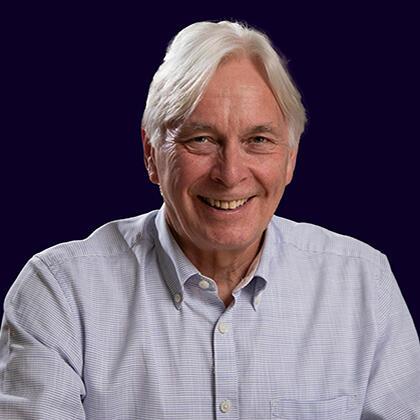

Professor Martin Elliott

“If you're not making someone else's life better, then you're wasting your time. Your life will become better by making other lives better.”

― Will Smith

Introduction

These Gresham lectures have given me the unusual privilege of being allowed to talk in public about what I do. One of the most common questions I have been asked has been; ‘What does it feel like to hold a baby’s heart in your hands?’ Because each surgeon will have his or her own response, I thought it would be interesting to gather the thoughts and observations of paediatric cardiac surgeons from around the world. The lecture is based on video interviews I have carried out with my international colleagues, and will, I hope, give you a flavour of what makes them tick. Surprisingly few of them had ever spoken publicly about any of their feelings or indeed about their work in general. They were surprised to be asked.

I have been completely dependent on the openness and honesty of my peers. They gave freely and generously of their time. I have been both honoured and humbled to discover how dedicated are my peers and how humane they seem, as the words of Jeff Jacobs exemplify.

Professor Jeffrey Jacobs, Johns Hopkins University, St Petersburg, Florida, USA

“Everybody wants to have meaning in their life and make a contribution. And there’s perhaps no better way to wake up in the morning, look at yourself in the mirror while you are brushing your teeth and think, ‘Today, if things go well, I’m going to help somebody; I’m going to help a family; I’m going to make a difference.’ It’s going to require every ounce of energy, every ounce of intellectual ability, every skill I have. But if I do it well, it’s going to make a difference, it’s going to help somebody, and it’s maybe going to make it so somebody can live.

The ability to make a difference like that…that’s why we do what we do”

Often, surgeons get a ‘bad rap’ for an overbearing, arrogant or patronizing attitude, but I found the depth of thought and clear sense of responsibility exposed in these interviews very uplifting and to contrast completely with that reputation. I hope you feel the same.

Operating on a Child’s Heart

The work we cardiac surgeons do is a fascinating mix of craft, risk management, leadership, teamwork and basic medicine. Once you begin to be able to do the surgery, this heady mix overtakes you, as Tom Karl describes.

Professor Tom Karl, Johns Hopkins Medical Center, St Petersburg FL USA

“Surgery is like a narcotic. You start it and soon, no matter how much the price keeps rising, you can’t get enough of it.”

What we do is inherently risky, and any mistake we make may have lifelong consequences for the child and its family. Margins are very small, and in a new-born baby the heart really is the size of a walnut, and its component parts are thus even smaller. One slip can be fatal.

Luca Vricella provides a graphic description of this intensity.

Professor Luca Vricella, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA

“So if I have to describe the feeling of operating on a new-born heart. I think the perfect analogy is that of driving a car at 200mph on a single lane with water on either side. There’s no room for error. I think it’s the most exhilarating, yet humbling experience that you can possibly have. So to just…summarise it; paediatric heart surgery is the perfect balance between courage and fear.”

On top of all that, lies a deeply emotional layer, since we are dealing with children and families, who are often at their lowest ebb. We form relationships with them, which makes for a job of great intensity. Luca Vricella continues: -

Professor Luca Vricella, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA

“You have to be willing to have a long-term relationship with these children. It’s not in the operating room. As I say to parents, you know, our relationship is not limited to this day in the operating room.

You don’t want to see me, but I want to see that postcard at Christmas!”

It is difficult, without sounding trite, to express to non-surgeons the reward associated with being able to correct a child’s heart. Most of us regard it is a privilege to be allowed to do what we do, working with wonderful people. Christian Kreutzer elegantly sums up these rewards:-

Professor Christian Kreutzer, Buenos Aires, Argentina

“Maybe we cannot save this child, but at least we should give the child all the love that we have and the family all the love that we have. And if we are not able [to save them] then at least this will be the way that we will live best….knowing that we did the best we can. He added, ‘Find a job that you love and you don’t have to work anymore’.”

Surgeons interact with patients in different ways because of their own personalities or because of the system in which they work. Patients may be referred directly to them, or via paediatric cardiologists. Decisions about what to do by way of treatment may be made jointly by the cardiologist and surgeon, or more commonly at some form of larger multi-disciplinary meeting (MDT). MDTs provide a forum for a combination of protocol-based decisions and technical decisions. They address broad ranging ethical issues about the relative value of a particular course of action to the child. There will also be extensive logistic debate about prioritisation of one patient over another, taking into account medical, social, capacity and, increasingly, financial issues.

The first time the surgeon meets the child and family varies from centre to centre. In some units, the surgeon sees the patient well in advance, in a separate clinic, to discuss the surgery, whilst elsewhere there is more of a team approach with the operation being described by the cardiologist as part of the build-up and thus meeting the surgeon is postponed until just before surgery. When I started doing heart surgery in the 1970s, the relationship I was able to build up with the patient and the family was a crucial part of the work, and to me at least, emotionally important. I needed to understand what their expectations and anxieties were in order to give my best service. Such a perception remains with many of my colleagues, but it is interesting that some, and in that number I would include some of the very best surgeons in the world, do not feel it necessary. Many regard their part in the treatment of a child as largely technical in nature, leaving continuity of care to the cardiologist. Or they simply sublimate their emotional involvement in order to free themselves to do their technical best. For example: -

Professor Victor Tsang, Great Ormond Street, London, UK

“I like to see the child before surgery; I like to have an image of that child in my mind. But I try not to have too strong an emotional link, because I think my job at that very moment would be to deliver the highest quality of surgery to get the child through the operation.”

Professor Emre Belli, Paris, France:

“I don’t like to see too much the patient before [the] procedure. I see and talk long with parents to explain what’s going on and what are the risks and outcome…expected outcome. But I try to keep a distance, at least for the first procedure, with the baby or the children, probably in order not to put too much emotion in the engagement which we have, and to make it…. more technical”

Mr. Ben Davies, Great Ormond Street, London

“Think about the way the drapes are in the operating theatre. They are all opaque. Yes, they are all sterile and it helps our eyes adjust to the field of interest, but they are opaque for a reason. In order to process it yourself, you have to come to work every day, do the same thing every time. I’ve got two young children at home, and, to a large extent you do de-personalise it in order to do something day in day out. Most of the time it goes well, but sometimes it goes less well. And you need to be able to deal with that and to come back after reflection and to carry on”.

Others see the emotional side of our work as integral;-

Professor Bohdan Marusweski, Warsaw, Poland

“A lot of sensitivities, a lot of emotions. We are all very emotional, even if we cover it, if we don’t show it; inside ourselves we are very emotional. A lot of responsibility for patients.”

Prior to surgery, surgeons demonstrate a variety of methods of mental preparation. A well-prepared surgeon is calm under pressure and will have worked out a variety of ‘get out’ options and agreed these with his or her team at the start of the list and again at the start of the case. One of my early mentors used to come into the hospital in the early hours of the morning before a big operation and could be found pacing the corridors mentally rehearsing the procedure and emotionally psyching himself up. Most of us start to get mentally ready the day before the surgery, making final preparations before we leave the hospital. One does not just need to plan for what is likely to happen, plan A, but also for the worst; plans B, C or D. As final preparation some, myself included, use the journey to work mentally once again to rehearse the steps.

The surgeon will meet the family early in the morning of surgery, not just to reassure them, but also to mark, with indelible ink, the skin of the patient at the site of the planned incision. Nobody wants to operate on the wrong part, and cross-checking the plans with patient, family, medical records, surgeon and nurse mitigates the awful risk of such a never event and induces confidence and trust. If you have to have an operation, makes sure your skin is marked on the side you agree!

The day of surgery begins, nowadays, with a briefing for all the staff in the operating theatre. The purpose of the briefing is to ensure that everyone knows each other’s name and role, and that everyone knows what is planned for the day. Teams and team members change constantly, and the briefing gives everyone the opportunity identify themselves, to ensure that all the necessary equipment is available, that there are appropriate staffed beds for the patients post-operatively and that everyone is aware that speaking-up is encouraged. It also allows the back up plans to be shared and agreed.

After the briefing the patient is sent for and brought to the anaesthetic room by staff skilled in making the child and family feel at ease (or as at ease as possible), despite having to travel along a scary hospital corridor. Our team, led by Mike Stylianou, runs a programme called ‘POEMS’ designed to reduce child and family stress at this time (you can read about it here; http://www.poemsforchildren.co.uk/). The POEMS programme has proved remarkably successful, and it always amazes me to see how relaxed most children are when faced with such an intense experience.

We are really lucky in the UK that there are anaesthetic rooms. In many countries, there is not such space, and the poor patient is wheeled directly into the operating room to be scared rigid by the sights and noises off. Anaesthesia is begun, and whilst the anaesthetist does his or her work setting the child up to be as safe as possible during the operation, the surgeon can get on with something else; and there is always plenty else!

Once anaesthesia is complete, the patient is wheeled into the operating room, and connected to the monitoring and the ventilator. Everything is checked again. Identity, planned procedure and location of planned incision; and a further affirmative statement is made to all staff that it is OK to speak up. Calm is generated, the patient’s skin is prepped (cleaned and sterilised), draped with sterile towels to isolate the field and the surgeon asks permission of the anaesthetist to make the incision.

In most operating rooms, a trainee surgeon will open up, so that they can gain experience of the various steps in the procedure. Most of us remember our early cardiac operations as being something special, but I do not think many have been elevated to the plains of heaven like Tom Karl:-

Professor Tom Karl, Johns Hopkins University, St Petersburg, FL, USA

“I can tell you, the first time I was involved in a new-born operation it was like a religious experience. I couldn’t believe I was there, I couldn’t believe what we were doing, I couldn’t believe how much more my chief, Hillel Laks, knew about this than I thought I would ever be able to know. And I was really just taken to another place by this”.

For even the most experienced surgeons, the incision feels like the opening act of the performance. Everything has led up to this. There is no fear, but the start of intense concentration. If you lose that concentration and focus, you put everything at risk. It is a moment when most of us recognise the importance of confidence. Not just the confidence to make the incision (we all remember our first time) but also the confidence that you can do the operation, from start to finish; that you will be able to fix the problem.

Professor Morten Helvind, Copenhagen, Denmark

“I think you have to be very confident. I think it would be impossible to go into the operating room with a felling ‘that I can’t do this’. You have to go in with a feeling that I can solve this problem, even if you have some idea that it might be difficult. Then you have to have this self-confidence that you could do it.”

Mr. Mike Stylianou, Practice Educator, Great Ormond Street, London, UK

“Most surgeons, I have to say, in my experience are…There’s a degree of eccentricity, there’s a degree of arrogance, and I’ll qualify that in a moment. To open someone’s body and stick your hands inside and jiggle them around;….if you’re not confident, you’re never going to able to do that. So when I say arrogance, I mean perhaps a misinterpreted confidence. And that confidence doesn’t come out of a Christmas cracker, it comes out of years, and years, and years of practice. Over, and over and over again.”

Once the skin has been opened and any bleeding controlled with cautery, the sternum (breastbone) has to be divided, with a power saw, to allow us to get to the heart. This is a part of the operation that visitors and students hate. The noise is definitely not natural, and the idea of sawing through a bone with the heart directly underneath creates mental pictures none of us like! Fortunately, the saws oscillate, and whilst great at getting through bone they are (fortunately) lousy at getting through soft tissue.

In most ‘first time’ surgery, the heart is separated from the back of the sternum by a clear space, the thymus gland and a natural membrane wrapped called the pericardium around the heart as a sac. We remove part of the thymus and open the pericardium. And there is the heart, beating away beneath our eyes.

This is the phase of the operation when the surgeon, for the first time, engages directly with the heart. It is a surprisingly tough organ that tolerates touch and displacement quite well, keeping on beating even as we move it around and put stitches in it. Learning to place stitches in a moving target is one of the wonderful mysteries of our training. But asking my peers the question of how it feels to hold the heart, brought forth a range of responses, ranging again from the emotional to the detached, and from the mystical to the practical. Let us hear from them: -

Professor Jeffrey Jacobs, Johns Hopkins University, St Petersburg, FL, USA

“Holding the heart of a little baby in ones hands is the most powerful responsibility that exists. As you hold that heart in your hand, you think, well, the life of this baby is in my hands, and the hands of our team. I think we remember that this is perhaps the biggest responsibility that an individual can have”

Professor Sertac Cisek, Istanbul, Turkey

“Holding baby’s heart in my hand…..we all love our children, and it’s a huge, huge responsibility on your shoulders to have somebody’s children’s heart in your hands. However, as big as this responsibility is; is the pleasure and is the joy of repairing the heart and seeing the light in parents’ eyes. That is a huge, huge pleasure.”

Mr. Olivier Ghez, Royal Brompton Hospital, London, UK

“There was another time which was very significant. It was the first time I operated on a newborn baby for a complex congenital condition, and this time I really realised how mad you have to be to do this, to do this in a small baby. It was just as small as this [demonstrates 3D model]. For a very technical operation you are very focussed on the technicalities, but at some point you realise you have a little baby in your hand, and it becomes very scary”.

Professor Lorenzo Galletti, Bergamo, Italy

“There is a physical part when you touch the heart. In this moment I think the emotional part is less but sometimes arrive to me in my mind to think about the history that I have said to the parents…I try to avoid that; to be as cold as possible. But human beings… not always arrive to do that!”

Professor Viktor Hraska, Sankt Augustin, Germany & Milwaukee, WI, USA

“You have to find a balance; this professional balance, to somehow push away these emotional feelings and to concentrate on your work. So, when you ask me how I fell when I touch the heart, I want to get the job done as quickly as possible and in appropriate quality. That’s [the] most important thing. I even think that if you are a bit emotional during the operations that can even, somehow has a negative impact on your decision making and the way how you handle the critical situation.”

Duccio di Carlo, Rome, Italy

“Well it felt like having life in your hand. Just like a very symbolic feeling. Almost as a feeling of owning the person. Possession. This person is now mine for the time that I do something for him. This person belongs to me; and this gives me obviously an enormous positive feeling and at the same time an enormous responsibility. So there was a double side to this feeling, but the feeling was something of ownership.”

Professor Jose Fragata, Lisbon, Portugal

“Well, thinking that with your hands, that little heart on the tip of your fingers, you are able to recreate anatomy or to transform physiology. So, basically at that moment, sometimes it’s scary. Afterwards it gives you pleasure, but before it gives you worry!”

Professor Morten Helvind, Copenhagen, Denmark

“Well, the first time you were assisting as a young surgeon it was very magical because you were a kind of spectator and experiencing something for the first time. When you stand there as the surgeon yourself - with the responsibility, I think it is a very different experience. Mainly I think of this as a mechanical thing. I work on a machine; I try not to think too much about the fact that this is a baby with parents and a lot of emotions around. I try to isolate myself from that because I think it’s difficult to do a good job if you are thinking that I cannot afford to fail. It’s better if you are detached, actually.”

Professor Viktor Hraska, Sankt Augustin, Germany (shortly to take up the Chief’s post in Milwaukee, WI, USA)

“I think it is necessary to differentiate between ‘the job’ and this ‘emotional background’.”

Mr Ben Davies, Great Ormond Street, London, UK

“ I don’t actually feel anything. I think, metaphorically, the way I would choose to answer your question is ‘to be responsible’ for someone, for someone’s being. But I think it can be a distraction to actually think about it whilst you are doing something.”

Mr T-Y Hsia, Great Ormond Street, London, UK

“ The feeling changes obviously, because as a registrar or trainee, sure you got a heart in front of you and you’re holding it, but you’re not responsible for whatever happens. But I do remember, you know, the first few cases when I had the heart in front of me and ‘I am it’. I have no parachute, no more protection, and whatever happens with that heart is on me. And I remember that gravity; all of a sudden you are hit with that gravity of the situation. It’s a mixed set of emotions of a bit of nerves, anxiety, how’s it going to go, is it going to go well….my whole career’s in front of me!”

Professor Christian Pizarro, Wilmington, DE, USA

“I would say generally I try not to hold the heart, and try to be very gentle. I think that’s pretty deliberate and to a great extent I learnt through a surgical school where you tried to deal with the heart through the end of your instruments, though the instruments are the extension of your fingers, so to speak. The emotional component for me is mostly about the tremendous responsibility and the accountability that you are held to.”

Professor Ilka Mattilla, Helsinki, Finland

“Well, it’s more or less a technical procedure when I do the operation itself. And at that moment, I don’t have very much emotion. It’s more like handcraft. And you don’t think about the baby itself.”

Professor George Sarris, Athens, Greece

“I think it is fair to say that most of the time, certainly now and for years, when manipulating or operating on a baby’s heart you don’t feel anything….because I think we are trained not to feel anything. Because we focus on what is necessary to do. I think subconsciously, and maybe at different levels, there are many feelings. I think probably the strongest one for me would be a feeling of great responsibility; to the baby; to the parents; to the team, because I am leading them into this adventure; and also to society. But I think these feelings are not there; I mean they are there subconsciously.”

Professor Giovanni Stellin, Padova, Italy

“Well, to hold the baby’s heart in your hands might be emotional for someone who has never done it. Of course for us it is not emotional any more. There are so many other steps before that, that indeed are very emotional. For instance, for me it is still very emotional going to talk to the parents before the operation; to see the child, perhaps with very complex congenital heart disease, and with a chance that they might die.”

My colleague, Victor Tsang, has a very Confucian perspective.

Victor Tsang, London, UK

“Well. Well I do try to…….understand the…..strength of the heart. Not only it is a beautiful pump, but it is so soft and at the same time it is so strong. And in the vast majority of the patients, the heart is very kind.”

Professor Emre Belli, Paris, France

“It’s always an exciting thing, but not in the level of a human being’s heart in my hands. It’s this wonderful creation which has some problems at some level after development that you have to solve in the best way without harm and minimum damage, and this is how I feel.”

Most movingly, and almost agonisingly honest, is this from Antonio Corno now in Leicester, having worked all over the world, reflecting some of the tensions which all cardiac surgeons have gone through in their professional lives.

Mr Antonio Corno, Leicester, UK

“At the beginning, when I was very young, so a long time ago, I couldn’t separate the technicalities of the operation from the fact that I knew the child and the family. And this was a total disaster because my emotional feeling was giving a lot of problems to me when things were not following the expectation. And after one or two cases where the child was very, very sick after the operation, I decided that that was not the way to work as a paediatric cardiac surgeon. I had to learn to completely separate the technicalities of the congenital heart defect requiring the repair from the fact the heart was the heart of little James or Hannah or whatever you want to call… and it took some time, but this is what saved me, otherwise I would have stopped doing this.”

To be able to operate on the inside of the heart, the child must be placed on cardio-pulmonary bypass; connected to the heart-lung machine. After anti-coagulating the blood of the patient with heparin, we have to insert pipes into the major veins returning blood to the heart, so that the venous (blue blood) can be drained under gravity into a reservoir and then pumped through an oxygenator back through another pipe inserted into the aorta, thus bypassing both heart and lungs. To insert the pipes we must make holes in vessels which are carrying the whole cardiac output of 4-5 litres of blood per m2 of surface area, so to stop bleeding we place purse-string stitches around the places where we want to put the pipes, and then tighten these sutures so that there is no leak around the cannulation site. In our early lives, this can be very stressful, and prone to embarrassing moments. The fear of sticking a scalpel into a vessel carrying of much blood is profound when you first do it. And everyone is watching you, to see how you do.

Professor Mark Hazekamp, Leiden, Netherlands

“Yeah, well it’s quite scary. I remember the first time I had to cannulate, it was an adult patient, the first time as a resident putting an aortic cannula in. I was scared stiff, and then I made a hole, put a cannula in but too late, so I was covered in blood. That was my first experience with aortic cannulation, yeah. But that, you know, goes away rather rapidly!”

Professor Lorenzo Galletti, Bergamo, Italy

“I remember the first time. I was really emotional, and I passed very close to put the knife into my hand instead of the heart! The knife dropped very close to my finger!”

Mr. T-Y Hsia, Great Ormond Street, London, UK

“I won’t say it makes me nervous; it’s certainly a step of the operation that we do so often. Even though we do it every day, it’s still one step where I typically take a little old deep breath before I do it. You know, I slow down a little bit.”

Assuming bad things like this don’t happen, bypass (CPB) can then start and we can prepare to stop the heart and isolate it from the rest of the circulation.

We have to do this to be able to operate on the inside of the heart…open-heart surgery. A cross-clamp is placed across the aorta, stopping blood flowing down the coronary arteries, and cold cardioplegia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cardioplegia) is infused into the aorta to the heart side of the cross clamp, flushing the coronary arteries (which take origin from the aorta just above the aortic valve on the way out of the heart) with cold fluid high in potassium. This stops the normal contraction of the heart by interfering with the flow of ions across the cell membrane. The cardioplegia can be re-injected at intervals during surgery to maintain protection of the heart and keep it arrested, and the heart can be kept cold by surface cooling with ice.

The combination of CPB and cardioplegia allows the heart to be opened and repaired, whilst keeping the rest of the circulation, and especially the brain fully perfused and free of air. There is a time limit though, as even at the low temperatures induced by flushing the coronary arteries with cold cardioplegia, the heart is still slowly metabolising and without blood and oxygen it would gradually deteriorate, become damaged and perhaps not start again when the internal repair is over. Fortunately, this is very rare as we have managed significantly to improve our techniques and equipment, but open-heart surgery remains ‘time-limited’, and not all surgeons feel comfortable working under those conditions.

After the inside of the heart has been fixed, the aortic cross clamp can be released, and the warm blood circulating around the rest of the body can then flow down the coronary arteries, flushing out the cold cardioplegia and any metabolites that have accumulated. Oxygen, an appropriate electrolyte concentration and nutrition are re-provided to the heart cells and soon it begins to beat on its own once again. For many surgeons, it remains a remarkable moment.

Jeff Jacobs

“When a heart sits in the chest not beating while we repair it and then all of a sudden when we are done with the repair we give blood to the heart and it starts to beat; that is a very powerful, exciting and awesome moment.

Mark Hazekamp

“Every time the heart starts beating, and especially when I look to the EKG and I see a normal EKG, - that’s good. And you know, it gives me joy, and then I think, well, again a case that was solved.”

Sertac Cisek

“It is miraculous, I believe; it is something miraculous.” “When you take the clamp off and then you see the heart beating again, it is just a miracle to me.”

Victor Tsang

“One, would be the moment of joy, that it is the completion of a very difficult operation. On the other hand, it can be a moment of uncertainty because the repair may not work, the heart may not work well right away or the rhythm of the heart may not be coordinated. So it is a bit of a mixed emotion”.

Duccio di Carlo

“It’s almost magical!”

Antonio Corno

“It is always a very stressful or challenging situation, until you see the heart beating with the rate you want and the colour you want and you feel completely…relief. The operation is not yet finished but you know then; 99% of the cases at this point you can go and talk to the parents and tell them, everything is fine.”

Luca Vricella

“So, the first time that I saw the heart start again was in an operating room in California. It was a heart transplant in a baby. And this was 23 years ago. And I fell the same exact way when its starts again 23 years leter. It’s that emotion, that sensation of …you know. To me it’s just an amazing feeling. To me there’s nothing more powerful; nothing more reassuring than when you see that heart start, and start vigorously. You know that it’s going to be OK.”

T-Y Hsia

“So for me, once the heart starts to beat, and have a rhythm, I don’t get a sense of achievement, but a sense of relief….I’ve escaped”.

Jose Fragata

“That gives you a sense of power and control which all human beings like, you know. You are able to open, arrest the heart and then bring it back. It’s a bit, maybe for the pilots flying ..it’s take off, cruising and landing. And I presume when they land nicely it’s quite a relief!”

Victor Hraska

“Well sometimes I speak with him [Q. with the heart?] I said “well, just start to work; it’s your job”. That works; it’s amazing. After so many minutes being completely flat the heart all of a sudden starts to work and you see how nicely it’s contracting and so on. This is extremely rewarding feeling after the operation because you have a feeling that, well, it’s moving in the right direction. If not, I try, you know, to tell him “Let’s start to work please!”

Tom Karl

“Well I must say it’s a beautiful thing and for some of the babies, some of our patients it’s, you know, in many ways a new beginning for them. I think it’s actually my favourite part of the operation. The baby’s heart is speaking to you, telling you that you’ve done the operation correctly and your actually going to get separated from the heart lung bypass machine. I’m going to survive, I want you to know that and then you make that all happen. So, yeah, it’s a good point in the operation.”

Ilya Yemets

“That’s most enjoyable, and even I would say, could replace some food! I’ve never felt that I am hungry during the operation, never. It’s exciting, that’s true!”

George Sarris

“Nothing particular. Because our field has progressed so much that it is expected it will start. You know there is a feeling of satisfaction, but its mostly not a feeling, it’s just..it’s done, it’s done”

There are over 3500 individual anomalies of the heart and great vessels that need to be understood, and 2500 individual procedures that the paediatric cardiac surgeon has to learn during their training (http://ipccc.net/). You will be glad to know that I am not going to list those, but it is important to realise just how much a paediatric cardiac surgeon has to hold in their heads both in preparation for surgery and during the operation itself.

Because of modern imaging techniques, we usually know with great precision which of these anomalies we will encounter and which procedure we plan to do. However, there remain variables such as tissue fragility, the severity of adhesions and other factors that cannot yet be accurately predicted. These variables, combined with anatomic complexity, and varying physiology, when combined with the time limits imposed on the surgery, create excellent conditions for stress, especially for the surgeon. Surgeons do sometimes find situations getting away from them, and potentially they can ‘lose control’ of the situation, their team or their emotions.

I asked the surgeons if they had ever lost control in the operating room.

Martin Kostolny

“Yes, I think all of us who are in this job sometimes feel very helpless, when things go terribly wrong. And sometimes you feel that there’s something I should be able to do. Sometimes you can’t. And it’s a very bad feeling……What I think, well, How do I go and (is something like that happens) how do I go and…how do I explain it to the parents? That there is nothing I could….nothing more…I mean I almost feel that I…can’t tell them that, there is nothing. It really is like a phrase then “ there is nothing else we could do”. Because you feel like, ‘there must have been something I could…..”

Professor Emre Belli

“Yes. It happens. In many conditions I had this situation - that I was not driving, but I was running behind the situation. Your mistake is often decisional, because hand [related] mistakes are very rare, despite [what] people are believing. But the mistake is to underestimate the case. In other surgeries you can catch whatever you do, but in children - if you do something wrong you know..the game is over. For that reason we are in a permanent tension.”

Professor Bohdan Maruszewski

“Oh Yes. That happens. It happens that things go worse or quite badly or worse than you expected. I think it’s always the moment when I think ‘how am I going to save this child; how to finish this operation [in] the way this child survives?’”

Professor Viktor Hraska

“It’s interesting, actually, how memory works. Usually you remember all your disasters, but to make our life easier or better, we call these disasters experience. So we have a lot of experience from this standpoint of view!”

Professor Christian Kreutzer

“There’s one thing I hate. It’s not..er..incompetence. It’s just people who doesn’t care. Because everybody can make mistakes, but not caring about making them, is what actually makes me very angry.”

Morten Helvind

“You have this feeling that things might not go well, and then you have first, a short while, a very short panic; because you can’t afford to panic. And then you go back on being systematic. You try to think, ‘what are my options?’ In cardiac surgery, because we have the heart lung machine, we can always think, take a short break mentally and think, before you do what you have to do. Then you just work your way through it, and as soon as you have a plan the emotions go away and you just to the manual job, basically.”

Professor Giovanni Stellin

“Well it is a very dismal feeling that you might lose control of the operation. Nevertheless, you never lose the hope that you might be able to go back to the normal status of the operation, and regain what you lost. It is obvious that, at least in my institution and I think in all institutions, things are prepared in all their details. This is difficult for the Italian mentality, because we Italians are not prepared to program things inn ‘the proper manner’. So when I transferred the package that I gained from the United States and Australia it was difficult for me to transfer all those kinds of information and train the personnel in ‘the proper manner’. Nevertheless, I did! And the programme I have in Italy…I am very proud of it.”

Duccio di Carlo

“Well, I frequently lose my temper at the table because I am very emotional. And definitely in the moment when things seem to be going wrong, one starts to think ‘I’m going to lose this baby; this is my fault; I am going to have to tell the family that I made a mistake, that everything goes wrong”. Everything goes back to what I said before; “I own this child, and now I don’t own it anymore. I lost it. It’s my fault. So…..”

I am sure that by ‘ownership’ Duccio means that personal sense of huge responsibility, which emerges as a common theme in these interviews. It is clear that the burden of caring for someone else’s child in such a direct, physical way is deeply felt. But no amount of beating oneself up can compensate for planning the importance of the team around you working together to help the baby.

Professor Christian Kreutzer

“If I notice that I made one mistake, I obviously became very angry and say “How can I do this?”. [Q. Do you get angry with others?] No, no, with myself. [Q. Would other people in the operating room be able to see you were angry?] Well I try not to, I try not to and they say I’m nice in the OR, but I’m the boss so….!”

Professor Victor Tsang

“I may be feeling out of control inside, but on the outside a try to maintain a certain composure, because it is very important at the time of crisis there must be some leadership because everybody in the operating room is looking at the surgeon to direct them what to do next. But the feeling of your [own] heart sinking slowly, slowly, slowly down to the level of your ankles can be very unpleasant.”

Mr. Ben Davies

“So, most of it is actually trying to avoid that sort of event with anticipation and planning. But when it does happen, sure, I’m human. You do have a reaction inside, but it’s never helpful to manifest that, because as long as you acknowledge to the people around you that you are in a tricky situation and need their help and attention. If you were to manifest it in a classical way by raising your voice or doing something else, then it’s quite obvious that you don’t get the best out of people who are trying to help you. Some people can be ‘more lively’ than others, but I don’t see the logic in turning off the very people who are there to help you and to work together with. Behaving in a different way has far less fruitful benefits".

Mr. Olivier Ghez

“Yes, I think there are moments when it becomes very complicated and you have an acute feeling that you are losing the baby. But sometimes you feel you are inflicting harm and you don’t manage to get a better outcome and it gets worse, and worse and worse. It’s a horrible feeling. Hopefully in most cases you manage to turn it around and get back on your feet and reverse the situation, but it’s a horrible feeling. But this is a moment you must not completely crumble to panic. And I think if you show everyone that you are in a complete panic, then everybody panics and then the whole team is unable to work. So I guess this is a moment when you just slow down and appear more in control, even though you don’t feel it.”

Professor Tom Karl

“There are many times when I have felt out of control. It’s usually some chain of events that happens, starting with one small thing that leads ultimately to some big and terrible thing. There is a lot of room for error in a paediatric cardiac operation, and there are many people involved.

I think what I could recommend, about a moment like that, is that if you can’t keep it together, neither can anyone else, and lashing out at the only people on the planet who can get you out of that situation at that moment is definitely the wrong strategy! I think as surgeons, many of us have missed that in our life training.”

There is still much to do. There may be things outside the heart to fix, and one has to be sure that the heart is working well enough to take over from the heart lung machine. This process is known as ‘weaning from CPB’. Very careful teamwork and excellent communication are needed at this stage, as the new anatomy of the heart, and a different circulation, have been created. Various drugs are needed to minimise the work of the heart and to facilitate the flow of blood through the body. The anaesthetist leads on this, according to protocols developed over years. But each child is different, and the team must be able to react appropriately and quickly to any problem. Being able to wean a child from cardiopulmonary bypass on minimum support is another magical part of the operation, and one of the key times when the surgeon can begin to be sure that the operation they have just done is going to work. It is a time when they can begin to relax a little and, whilst still focussing on the job in hand, breathe a little easier.

You cannot relax completely however. The heart is at its most vulnerable at this stage and the child’s other organs are dependent on it working well. It is crucial that the whole team carefully monitors the child at this stage. Change can be rapid, and so must be the reaction of those caring for the child. Once again communication and teamwork are vital. In the current era, we are able to check the quality of our work much better than we could in the past, when we just used to have to send the child back to the ward and ‘see how they did’. Now, using trans-oesophageal echocardiography, we are able to see the inside of the heart, judge the quality of our repair, monitor heart function and use these data to decide whether to go back on CPB to revise the repair to give an optimal result.

Many of the surgeons have mentioned the team in their comments. Their thoughts are interesting.

Antonio Corno

“I totally agree with you that it’s a team sport; because any member of the team is contributing to the success of the procedure, and any member of the team can create a disaster in any moment.”

Lorenzo Galletti

“A lot of people has to work together. And that maybe is the most difficult thing to achieve and the most difficult task. To have people that work really together not each other as part but move like a football team for example.”

Giovanni Stellin

“Nowadays, not only in medicine, but also in Formula One, Ferrari, the same thing. Ferrari was having great results and at a certain time, it all started to go down. Why? Because you need to work as a team. Teamwork, that’s the name of the game. You guys from the United Kingdom taught us how to work as a team, and for us Italians….the ideal Italian wants to be the protagonist, that’s the problem. So to work as a team is extremely difficult. Nevertheless, it’s still possible. Teamwork, that’s the name of the game.”

I hope you can appreciate the responsibility held by surgeons in these circumstances. It is obvious from the interviews I have done that they feel this responsibility with great intensity, and it weighs heavily on them.

Here is Tom Karl again:-

Tom Karl

“The team approach is stressed over and over again but at the end of the day, it’s you and the sick baby and the baby’s mother and father. And it doesn’t matter how good or how bad your team is, the smoking gun is in your hand. And so you’d better make sure that; Number 1 you’ve done a good job on the operation; Number 2 that you’ve organised your team to perfection; and Number 3 that all the resources that you’re going to need to complete this operation are going to be immediately at hand should you need them. So, primary responsibility? I can’t conceive of a day when that won’t fall upon the surgeon.”

And Duccio di Carlo

“We used to say in Rome, first of all, it’s always the surgeon’s fault, always; for everybody, including the surgeon. When something goes wrong for a child, it’s always the surgeon that takes the blame. But that is something that we feel; the surgeons feel it. So our feeling is that we did something wrong, always…”

This responsibility takes its toll. It takes decades to become a paediatric cardiac surgeon, and the hours are brutal. Our patients are often very sick, and their status can change rapidly during recovery. Their lives are truly at risk, and they don’t necessarily get ill between 9 and 5! Surgeons need to be available round the clock, every day of the year, and be willing to drop everything to come into the hospital to resolve a problem. I remain surprised how, sometimes, even close friends don’t get this. Such relentless pressure, stress and crazy hours take their toll on the surgeon, and sadly on their families. I asked the surgeons about how their work, particularly the stress of hours worked and commitment to other lives under threat, had affected their family life.

Luca Vricella

“I think that responsibility has affected me as a human being, as a family man. I think that, more so than in probably most other specialities in surgery, we are what we do. We are on call 24/7, 365 days of the year and we are always responsible for our patients; we always go in in the middle of the night. You don’t delegate, you do it.”

Viktor Hraska

“I am not sure if they appreciate our endless effort to help these kids. Without any restriction. No, it’s not about the money, it’s not about the time; it’s about this mission to help, and to give a new life”.

Olivier Ghez

“It’s difficult to speak about our job in society. You, know, having a nice dinner and someone asks you “What did you do today?”. Are you really going to say that you had someone who was dying and blood everywhere, a disastrous situation with parents crying and yourself you are destroyed? And here you are supposed to have a nice dinner and share a few glasses with some friends? Yes, people have trouble understanding it. I think no one can really imagine what it means - unless you really do it. You know, the hospital world is hidden from most people and it’s a world apart. People have a lot of trouble imaging what goes on behind the walls of a hospital. So…”

Jose Fragata

“I think that the work of the cardiac surgeon, being so demanding, will necessarily affect all your family. I would say that all the family will end up being part of the team, because necessarily you bring home all the worries. It’s full, permanent, full-time job. So I think they will share my worries the day before, arriving home late in the day and the joyness or sadness if things do not go well.”

Bohdan Maruszewski

“You know the majority of your life, if you dare to operate on children’s hearts, is to wait for the phone call from hospital. So the life of the congenital heart surgeon is a bit different to what we think should be a normal, regular life. Of course that has an impact on the family. My wife next to me who’s experiencing all of that, with me; I know she’s a part of that. The whole home is part of my professional involvement, so it’s not a single person thing. You really affect people around you”

Antonio Corno

“It takes you 24/7..different from the Post Office job where you finish at 5 o’clock…that’s it. No, when you finish the patient is still there, can be still sick and they can need your help or you want to know how the patient is doing. So you are 24/7 in the job and this is creating the major problem on the other side, which is the family life. Because that’s the place where I found the most important difficulties in my personal life; to combine the expectation of a job with a family life. I cannot say I was successful.”

Victor Tsang

“It’s a difficult question, but I try to look at it this way. I think my family knows I love my work, and that’s why I think I’m quite good at it. At the same time, I think my family knows I love them and that’s why we try to achieve a bit of balance in the unbalanced relationship.”

Ilka Mattilla

“Life could sometimes have been easier. Your commitment is so huge, and sometimes you wonder whether you could have spent more time with your family and give your children a bit more instead of giving the other children [so much time].”

Martin Kostolny

“In the past I was told that I’m not able to focus on anything else but my job. So, clearly the attention I give to my job is…must be above what other people think I give to everything else.”

Olivier Ghez

“I think it’s very hard for people around you to accept the same sacrifices that you impose on everyone; on yourself and everyone. I think for the children…my 6 year old daughter, once I was called during the holidays to operate and she said “Is there no one else? It has to be you that goes to operate?” She was quite angry; she is still angry now when I have to operate when I am supposed to be with her. She understands, I suppose, - but still. I think for the families, for the people around us, for friends and families it’s difficult.”

Gilberto Palominos

“Out of my five children, four of them are physicians, medical doctors. And they complain about that. They could have their father, but they could not have the big amount of time they could have expected. You know, when you are hungry, it’s not enough to have a nice caviar sandwich; you need a big steak, a big dish, a big plate, you know…”

Giovanni Stellin

“Well, it is obvious that to be a successful paediatric cardiac surgeon you must dedicate most of your life to that, you are full aware about that. So it is obvious that I was lucky enough to have my wife who cared for the children, because staying all day at the hospital I didn’t have a chance to see my children that much. I neglect that. Nevertheless, I was so attached to the work that I do that I felt it was important to do in the proper manner. If you wanted to do [it] in the proper manner you have to dedicate a lot of time to it. And the, erm….I still love my daughters and my wife, obviously, so we maintain a very good relationship. I have to say that, honestly, they never say to me daddy, why did you not dedicate more time to me. I have to say that probably you need to dedicate the time (which is very short) the time that you dedicate to the family has to be very intense. I had a lot of hobbies in my life, and I gave up all my hobbies. The free time that I have, I just dedicated to my family.”

Summary

I hope I have shown you just a little of how paediatric cardiac surgeons feel about their job. They play down how it feels to hold the heart of a baby, but I hope their evident dedication, deep sense of responsibility, commitment to children and love of their work have left their mark. There is no talk of hours worked, or of money earned; they clearly want to do their job to the best of their ability. They know they must be available 24/7, 365 days of the year, and they recognise the pressure on their families. But the sense of duty, responsibility and sheer pleasure in doing the job means they would all choose to do it again. The new generation is just as committed, and even more thoughtful.

I feel honoured to have trained many of the surgeons you have seen tonight, to have worked with others and to have shared research, clinical ambitions and good times with them.

The hearts of children are in good hands.

Thank you

This lecture would not have been possible without the contributions of so many other people.

I most want to thank my son Becan Rickard-Elliott, a film-maker whose patience in teaching me to do basic editing has been crucial, and for whom, because of my slowness to learn, I must have been an endless source of frustration.

My wife Lesley for putting up with my absences, and being my number one critic.

Nizar Asadi and Nagarajan Muthialu at Great Ormond Street kindly obtained and provided some of the operative footage. Nizar also helped with editing and sound and gave much needed advice.

All the operating room staff at GOSH put up with enormous intrusion with good grace and great help.

The members of the European Congenital Heart Surgeons Association (ECHSA), the Latin American Society for Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery, and the American Congenital Heart Surgeons Society (CHSS) all were willing both to be interviewed and to be honest about their feelings. There was so much interesting material from these interviews that I have not been able to include in this lecture, but which is truly fascinating and which I hope will see the light of day elsewhere.

Individual interviewees.

Professor Emre Belli

Dr Gabriel Castillo

Professor Duccio di Carlo

Professor Sertac Cisek

Mr Antonio Corno

Mr Ben Davies

Professor Jose Fragata

Professor Lorenzo Galletti

Mr Olivier Ghez

Mr Karl-Michael Greunsche

Professor Mark Hazekamp

Professor Morten Helvind

Professor Viktor Hraska

Professor Jeff Jacobs

Professor Tom Karl

Mr Martin Kostolny

Professor Bohdan Maruszewski

Dr Ilka Mattilla

Professor Gilberto Palominos

Professor Christian Pizarro

Mr Alex Robertson

George Sarris

Professor Giovanni Stellin

Mr Michael Stylianou

Professor Victor Tsang

Professor Luca Vricella

© Professor Martin Elliott, 2016

Part of:

This event was on Wed, 25 May 2016

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham College plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login