From Tyranny to Athenian Democracy

Share

- Details

- Text

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

When – and how – did Athenian democracy begin? There is no unambiguous answer to this question. This lecture explores one plausible origin: the popular uprising in 508 BCE overthrowing foreign invaders (who had previously expelled an Athenian-bred family of tyrants). In the aftermath of that revolution, the Athenians – led by Kleisthenes – reorganised their political system to foster new identities and interactions. As further political and social changes were made, Athenian democracy took shape in the imaginations of contemporaries and of later generations.

Download Text

From Tyranny to Athenian Democracy

Melissa Lane, Gresham Professor of Rhetoric

16 October 2025

Abstract

When – and how – did Athenian democracy begin? There is no unambiguous answer to this question. This lecture explores one plausible origin: the popular uprising in 508 BCE overthrowing foreign invaders (who had previously expelled an Athenian-bred family of tyrants). In the aftermath of that revolution, the Athenians – led by Kleisthenes – reorganised their political system to foster new identities and interactions. As further political and social changes were made, Athenian democracy took shape in the imaginations of contemporaries and of later generations.

Introduction

Every day at Harvard University, student tour guides take eager tourists to the famous statue of John Harvard. The statue bears the inscription ‘John Harvard – Founder – 1638’. But as the guides relish pointing out, this is a statue of three lies. John Harvard was not the College’s Founder; he was just one of several early benefactors. Moreover, the College was not founded in 1638; it was founded in 1636, before John Harvard left it a substantial bequest of money and books two years later. And finally, the statue does not depict John Harvard. When the statue was commissioned in the late nineteenth century, no one knew what he had looked like, so it was modelled on a young student instead.

The story of the ancient Athenian Kleisthenes could equally be a story of three lies. Kleisthenes was described by a later Greek historian as having ‘established the tribes and the democracy of the Athenians’ (Herodotus [Hdt.] 6.131.1: more on the ‘tribes’ part later). Yet Kleisthenes did not overthrow a tyrant to institute democracy; that overthrow was achieved by a force of Spartans who were enticed (perhaps by Kleisthenes and other exiles) to free Athens from a family of so-called ‘tyrants’ (and whether or not they were fully ‘tyrannical’ in a modern pejorative sense is another question to which I shall return). Moreover, when a popular revolution did take place against a second Spartan incursion, Kleisthenes was not even there; he had slipped out of the city, albeit possibly to help regroup for battle. Finally, while Kleisthenes returned to the city to act in concert with the people as a founding figure of Athenian democracy, we have no idea what he looked like, any more than the nineteenth-century New World Cantabridgians knew the real appearance of John Harvard. In fact, the Athenians themselves never installed a statue of Kleisthenes, and while they certainly remembered him, they rarely mentioned him in public speeches or on the dramatic stage.

So just as the true role of John Harvard is veiled, so too the true role of Kleisthenes in Athens is veiled, and also contested. After all, you’ve probably never heard of him. Yet he was part of a moment in Athenian history that transformed the city from one in which non-elites had only a few, delineated parts to play in public life, to one in which ordinary male citizens of any economic status could participate in setting the agenda for public decision-making.

So while we are more familiar with the names of the great Athenian lawgiver Solon (whom I have talked about in several previous lectures) two generations before Kleisthenes, or the great statesman Pericles two generations after him, filling in the gap with the Kleisthenic moment has much to teach us about how democracy can be won, and how it must be lived. Indeed, the very unheralded nature of the Kleisthenic moment suggests that democracy is never once and for all. It is always a work in progress, which can be protected only by being repeatedly reinvented.

My main focus tonight will be on three key roles that Kleisthenes played, that I call: partnering with the people; radical redistricting; and establishing new powers of popular agenda-setting. In fact, the first of these conditioned the other two: it makes most sense to think about this package of reforms as ones that he spearheaded but that drew on and succeeded because of his more fundamental decision to align himself with already emerging expressions of popular self-assertion. But before we can get to those roles, we need to fill in some unfamiliar history of Athens: recalling the legislation of Solon, followed by the period of tyranny that came to an end just before Kleisthenes came to the fore.

From Solon to the Peisistratid ‘tyrants’

By the sixth century BCE [before the Christian, or Common, Era], Athens had evolved an elite form of government, but it was vulnerable to recurrent bouts of intra-elite jockeying for power, especially between various familial clans. As I have described in previous lectures,[1] the city decided to put an end to a period of factional strife by inviting Solon—an aristocratic poet who also engaged in trade, and so had cultivated ties across the economic spectrum—to lay down a new set of laws reconciling both sides. The new laws were a success and were never formally abolished. They accommodated a continuing role for elected political leaders holding the office of archon. Like most Greek offices, that one was defined by an annual term. An officeholder was not a king because they were subject to annual selection and other limits on their powers.

Nevertheless, some thirty years after Solon’s lawgiving, his distant kinsman Peisistratos, after having served successfully as a general, carried out an ingenious political ruse: he wounded himself, casting blame on his enemies, and inducing the people to set up a bodyguard for him. Peisistratos then turned that bodyguard against the people, using them to seize the acropolis and to take power as a tyrant.

That word, ‘tyrant’ (turannos), is the term that subsequent Greek authors used to describe him. But in Peisistratos’ case, it seems to have had an older and more neutral sense: meaning that he attained power for life not through heredity (as would a king) but through some other means (in his case, deception and force); and that he held that power in a way not limited by the bounds of established office.[2] In fact, Peisistratos had previously held the established office of general, and was a conventional kind of politician speaking in the assembly, before he schemed to set himself up as a tyrant. Having done so, he held sway until his death (once he had succeeded in consolidating his power on a third try, after having been twice temporarily ousted).

So while Peisistratos definitely held power outside the confines of ordinary offices, he was an unusual tyrant in not having been generally perceived by the Athenians or later authors as ‘tyrannical’ in what has become the modern pejorative sense. Indeed, both of our (related) ancient histories of the period (one from within the next century, the other a further century on) refer to him as having been ‘moderate’. The historian Herodotus refers in the fifth century to Peisistratos’ having overseen ‘moderate and good government’ after ‘he neither disrupted the existing political offices nor changed the laws’ but ‘managed the city in accordance with its existing legal and political institutions’ (Hdt. 1.59.5).[3] And our other main narrative for this period, the Constitution of Athens [AP] compiled in Aristotle’s Lyceum in the late fourth century BCE, says that he ‘ran the state moderately, and constitutionally rather than as a tyrant’ (AP 16.2) and that ‘it was his aim to govern in accordance with the laws (AP 16.8).[4]

Yet there is a worm hidden therein. For Peisistratos seems to have been the proverbial benevolent despot: benevolent so long as his will was not crossed and no one asserted a contrary power. He is said to have made concerted efforts to keep the people ‘down on the farm’, that is, to prevent them from actively engaging in politics. As one narrative puts it, ‘he did not want them in the city, but scattered in the country, and if they had enough to live on, and were busy with their own affairs, they would neither want to meddle in politics nor have the time to do so’ (AP 16.3). In fact, at one point, he literally ‘disarmed’ the people: he gave a speech speaking so softly that the people had to come forward to hear him, to a point where his henchmen could collect their weapons and lock them away. After the speech, ‘he told the crowd not to be surprised or alarmed by what had happened to their weapons; they should go home and look after their private affairs—he would take care of the state’ (AP 15.5).

With everything important left in Peisistratos’ hands, deprived of active popular vigilance’, the purported aim of maintaining the laws could not ultimately be sustained. It seems that although the laws remained officially in place, their significance in controlling power became gradually hollowed out. So despite Peisistratos’ initial aims (even if we take them as genuine) to maintain the laws, the Constitution of the Athenians would eventually sum up the legacy of his family’s time in power as follows: ‘Solon’s laws had fallen into disuse under the tyranny’ (AP 22.1). That spectre of legal fiction is one that we’ll meet again in my lecture on Augustus on 18 June—concluding the series on ‘Political Crises in Athens and Rome’ that I am beginning tonight. And Rome is far from the last place where that spectre may haunt us.

But for now, back to Athens. Peisistratos died in 527 and his eldest son Hippias took over as tyrant. One of the new young tyrant’s half-brothers outraged some powerful men in the city, who then conspired against the family: they were aiming to assassinate Hippias, but in fact, because of a mishap, ended up killing the tyrant’s full brother Hipparchos. Those two assassins would later be dubbed the ‘tyrannicides’; they would be lionized by the city as incarnations of democratic freedom, commemorated with statues, oaths and rituals, to be described in my next lecture on 22 January. But at the time, their intervention didn’t put an end to the tyranny.Rather the assassination prompted it to become worse: with Hippias punishing the assassins’ supporters and overall ruling much more harshly (5.62.2). He became much more tyrannical in the pejorative sense most familiar today.

With the crackdown on resistance, a number of Athenians (Kleisthenes among them) either went into exile or joined those already there. And from abroad, some of them came up with a clever ruse to gin up foreign intervention to liberate Athens: namely, bribing the priestess of the Delphic oracle (regularly consulted by Greeks from any and every polis) to urge any Spartan inquirer that the Spartans should free the Athenians from their tyrants (Hdt. 5.62.1). Being pious and suggestible, the Spartans eventually took up this advice, sending one of their kings, Kleomenes, to besiege the city. Nevertheless, the siege might have failed had not the tyrannical family sought to send their children to safety, only for the children to be captured—at which point the family bargained for Hippias and his supporters to go into exile (Hdt. 5.65.1-2) and so put the tyranny to an end.[5]

‘Partnering with the people’

So where does Kleisthenes come in? In the wake of the tyranny, there was a political vacuum in which he was one of two men struggling for power, against his rival Isagoras: ‘These two men competed for power, and when Kleisthenes found that he was facing defeat, he enlisted the common people into his association of supporters’ (Hdt. 5.66.2), or as another scholar has translated, ‘brought the demos into his group of comrades’.[6] I like to say that he ‘partnered with the people’. The dramatic nature of that decision can be understood by contrast with some of his predecessors. Solon had accorded distinct, but limited, political roles to the common people. But he had not aligned himself with them; on the contrary, he had taken care and pride in positioning himself in between the common people and the elite. Meanwhile, as I noted earlier, Peisistratos as tyrant had sought popular support, but had also ended up seeking to keep the people passive and quiescent. By contrast, Kleisthenes actively associated himself with the common people as his allies. Despite being himself from an elite background, he enlisted them on his side, as it were, being on his team, and making it clear to them that he would be on theirs.

And it was this strong and active association (a partisan association, as we might say) that generated the remarkable event of a few years later. At that point, the Spartans decided to intervene in Athens once again, to put Isagoras in charge of an even more exclusively elitist new model of the Athenian constitution. The same Spartan king and general seized the acropolis one more time. But despite the Spartans having previously served as liberators from the tyranny, this time they were seen as supporting a bid to exclude and devalue popular power. And while Kleisthenes and other leaders specifically targeted by the Spartans fled the city, both the officeholders and the ordinary Athenians resisted. ‘The Council refused to obey’ its ordered dissolution which the Spartans intended to use to put power into the hands of just 300 hand-picked citizens under Isagoras (Hdt. 5.72.2). And the Athenian people backed up the Council: they were ‘of one mind’ in besieging the Spartans on the acropolis and forcing them to leave under truce (while others were killed) (Hdt. 5.72.1-4). Josiah Ober has championed this as a moment of the formation of popular power,[7] albeit that it was also built (as others have pointed out) on the backbone of the Council as an existing institution. The result of the victory over the Spartans was that Kleisthenes was brought back triumphantly along with others who had been banished by the Spartans (Hdt. 5.73.1). And it was in the wake of this popular victory that a series of key institutional reforms was passed: most likely by Kleisthenes proposing them to the Council and Assembly.

We might say that the Athenians pulled themselves toward democracy by their own bootstraps: they acted as proto-democratic actors to create a partnership with a leader who was then able to institutionalize their power in new political structures and institutions. In other words, it was by treating the people seriously as partners, not as pawns, that Kleisthenes put an end to the cycle of intra-elite power struggles (of which the tyranny was part) and transformed the institutional framework within which the laws of Solon would henceforth (continue to) operate. In the rest of the lecture, I will discuss Kleisthenes’ partnering with the people, followed by three dimensions of that institutional framework—radical redistricting, establishing new powers of popular agenda-setting, and the extraordinary new Athenian institution of ostracism.

Radical redistricting

Recall that Herodotus credited Kleisthenes with having ‘established the tribes and the democracy of the Athenians’ (Hdt 6.131.1). In fact, if we ask what precisely he did, most of the political reforms under his aegis were about reorganizing the so-called ‘tribes’. Athenians had long been grouped into four tribes on the basis of birth and kinship. Kleisthenes abolished those longstanding ties, and instead ‘organized the Athenians into ten tribes’ (Hdt. 5.66.2).

Now this might sound pretty dull and abstruse. How could a change from four tribes to ten tribes be relevant to the establishment of democracy? Was all this stuff about tribes simply a side issue, before we get to the real meat of what he did to found democracy?

On the contrary. The reorganization of the tribes was at the heart of the Kleisthenic reforms that made Athens democratic, arguably truly democratic for the first time. For it amounted to a transformation of Athenian identities, akin to what Jean-Jacques Rousseau would later attempt in making ‘men into citizens’.[8] By abolishing the existing tribes, he made civic identity paramount, overriding ancient claims of birth and blood. And this was achieved through several interlocking dimensions of the reorganization of the tribes, which amounted to a wholesale reorganization of the city.

Consider first the fact that the new tribes were themselves products of the city—as opposed to being archaic rivals for political allegiance. Kleisthenes drove home their civic identities by ‘abolish[ing] the previous names of the tribes [which had been associated with ancient tribal deities] … [and] replacing them with names of local heroes that he discovered’ (Hdt. 5.66.2). In fact, the new tribes were able to accommodate the naturalization of a number of foreigners, expanding the citizenship again beyond the claims of sheer birth. That expansive, inclusive reordering of citizenship was expressed in the choice of one hero whose name Kleisthenes assigned to one of the new tribes: the Homeric hero Aias [Ajax], ‘who, although a foreigner, had been a neighbor and ally to the city’ (Hdt. 5.66.2).

A further facet of Kleisthenes’ reforms changed the form of the names used by each individual citizen themselves. To explain this, we need to look at a second dimension of the new tribes. They were built up out of trittyes (‘thirds’, with each tribe being composed of three trittyes), which were themselves constituted by combining a selection of ‘demes’: the new administrative atomic unit at the local level, based on preexisting villages or localities which were now regimented into civic subdivisional units. With ten tribes, the new trittyes were different from those which had subdivided the old four, and one later author comments that Kleisthenes refrained from establishing twelve tribes instead precisely in order to avoid too ready a mapping from the old tribes to the new ones (AP 21.3-4).

What the trittyes did was to combine groups of demes from the three geographical-cum-political regions of Attica: one group from the coastal region, another from the plains region, a third from the hills region (AP 21.4). (At least, that was the idea, though it was not carried out precisely).[9] This made the city legible in and through its newly restructured civic components: legible for top-down political functions, but more importantly, legible to and for the citizens themselves.[10] Indeed, whereas an earlier generation of scholars took the mathematical dimension of this restructuring to have depended upon elite philosophical achievements,[11] more recent scholars have argued that the very act of identifying and working with such numerical divisions, additions, and multiplications depended upon, and further fostered, basic civic competences that were fostered through games, military musters, and other everyday activities.[12]

By combining people into new groupings across these regional boundaries, sanctified by a new hero cult and empowered to carry out civic tasks, Kleisthenes created new wellsprings of popular capacity and common knowledge that would enable the Athenians to act together remarkably effectively.[13] And those local wellsprings were likewise dignified with a new set of naming practices. The old and new citizens enrolled in the tribes, women as well as men, were henceforth to be addressed not, or not only, by their father’s name (patronym) but by their deme affiliation (demotic. (It seems that Kleisthenes’ intention was to make the deme the key source of identification, though in practice, patronyms continued to be used as well.)[14] One historian has explained that ‘the intention to identify men by demotics rather than patronymics [was in part] so that new citizens would not become obvious’.[15] Yet the effect was not limited to the newly made citizens. Even for those as rooted in elite Athenian families as Plato and his family, to become known as ‘Plato[n] of Kollytos’[16] was to assert the primacy of belonging among one’s civic peers of all economic classes. Indeed, the demes were the gatekeepers of enrolment as a citizen when a boy turned eighteen:

‘his status was officially validated through registration in his father’s deme by vote of the demesmen, under oath, that he was of age, free, and born according to the laws…[as per AP 42.1, 3], and thereafter by the maintenance of the deme registers, which constituted the only comprehensive record of citizens which democratic Athens possessed’.[17]

Compare the power of Swiss cantons today to set specific conditions and determine naturalization as a Swiss citizen, albeit within federal law.[18] One’s relation to fellow demesmen became a potent source of civic solidarity.

Moreover, all this redistricting was understood a generation or so later as having itself been part of the ‘partnering with the people’ that Kleisthenes chose to pursue. Herodotus does not merely pair Kleisthenes’ work in tribal redistricting with the establishment of ‘democracy’ as two separate achievements; rather, he links and connects them, presenting the new tribal (and demotic) arrangements as effecting Kleisthenes’ aim of ‘adding the people to his side’ (Hdt. 5.69.2). This may have been partly simply by caring enough to organize them (Kleisthenes as the original community organizer), rather than ‘spurn[ing]’ them as earlier Athenian politicians had done (Hdt. 5.69.2). But it was also due to a further use of the new tribal districting that he established: that of populating, tribe by tribe (50 men per tribe), a new Council of 500. And that brings me to the next main theme of my lecture: popular agenda-setting.

Popular agenda-setting

One of the most important functions of the new tribes was to provide the basis for membership of a newly expanded and reformed Council (apart from the continuing Council of the Areopagus, which had a different set of roles). Solon had instituted a Council of 400 on which none of the poorest citizens sat (as membership in it constituted one of the offices for which they were ineligible based on wealth). Kleisthenes changed that to a Council of 500, for which each tribe was to choose 50 members by lot to serve on it for one year (with a maximum of two separated years of membership per citizen).

Now that might again sound like a minor detail: simply increasing from 400 to 500 members of a Council, akin to the simple numerical shift from four to ten tribes. In fact, the details matter: whereas the four tribes had each sent 100 members to the Solonic Council, the ten new tribes were each to send 50 to the Kleisthenic one. And more than that: Kleisthenes’ reconfiguration served to make Council membership into a much more widespread, regular and intensive civic role.

Among the powers and duties of the Council was setting the agenda for the assembly, by preparing the resolutions (probouleumata) which the Assembly would debate and vote upon. Agenda-setting is one of the three ‘face[s] of power’ which Steven Lukes analyzed in his classic theory of power.[19] And within democratic theory, it may be shaped by two different values, that pull in different directions. On the one hand, having a separate group role to decide on the agenda can make functional sense: it allows for deliberative input which is different in kind from the ultimate decisional vote. On the other hand, if a separate group is set up—something like an upper house in Britain or America, though each of those functions in a distinct way—that risks undermining the more general popular power concentrated in what we might generally call the lower house. In Rome, for example, as we shall see in my lecture on 11 June, the popular assembly charged with making laws was limited to voting for or against on the propositions brought before it, without its members being able to speak up themselves in debate or to shape the propositions themselves.

The genius of the Kleisthenic Council of 500 is that it could serve the functional role without undermining popular control: because it was hardly different in demographic composition from the assembly. True, any male citizen over the age of eighteen could attend and vote the assembly, while one could only serve on the Council (or in any other office) from the age of 30 and after having passed one’s scrutiny for being in good civic standing (dokimasia). But that was a very limited difference compared to most constitutional distinctions between upper and lower houses: contrast the House of Lords’ power to veto bills prior to the Parliament Act of 1911, for example. To be sure, the House of Lords as a body never had the power to set the agenda for the Commons. But the point is that Kleisthenes was able to gain the advantages of having two distinct chambers, with different roles, while preserving popular control of the agenda for popular votes: all by reforming the structure of the tribes and then the structure of the Council itself.

What was the result of all of this? Herodotus judged it to have engendered a sense of freedom. Under the Peisistratid tyranny, the people had in effect been ‘working for a master’, even though the laws and institutions from Solon’s time had remained officially unchanged. Whereas once ‘freed’ from the tyranny, they were able to enjoy ‘an equal voice in government’. And this, the historian indicated, had the effect of giving them enhanced military vigor and success. In 506, for example, just a couple of years after the revolution against Spartan intervention and the establishment of the Kleisthenic reforms, the Athenians managed to win two major battles on the same day: first against the Boeotians [Thebans], then against the Chalcidians. As Herodotus analyzes these achievements:

‘…the Athenians had increased in strength which demonstrates that an equal voice in government has beneficial impact not merely in one way, but in every way: the Athenians, while ruled by tyrants, were no better in war than any of the peoples living around them, but once they were rid of tyrants, they became by far the best of all. Thus it is clear that they were deliberately slack while repressed, since they were working for a master, but that after they were freed, they became ardently devoted to working hard so as to win achievements for themselves as individuals’. (Hdt. 5.78.4)

And as one modern historian put it in endorsing that assessment, the Athenian achievements due to their newfound freedom and organization continued to accrue: the Assembly (voting on resolutions drafted by the Council) made a number of good decisions, including keeping Hippias out when he tried to return, and fighting and winning the battle of Marathon as part of their successful contribution to Greek self-defense against Persian attacks.

‘…Herodotus has it essentially right when he says that Kleisthenes established a democracy at Athens. By means of resolutions passed by the assembly, the Athenians decided not to take Hippias back, to aid the Ionian Revolt, to march out to Marathon, to use the silver found at Laureion to build a large fleet, and to evacuate the city and defend themselves at sea against Xerxes’.[20]

Conclusion

In sum, in the words of Herodotus again, ‘Although Athens had been a great city before, it became even greater once rid of its tyrants’ (Hdt. 5.66.1). Athens flourished from the late sixth and early fifth century onward in the wake of Kleisthenes’ reforms. And its freedom was protected by one more of those reforms that I want to conclude by explaining: the introduction of the institution of ostracism. In fact, in my last lecture here, on ‘Lawgivers in Modern Revolutions’, I mentioned the English Levellers’ enthusiasm for this Athenian institution.[21] What I didn’t say then was that it was a product of what we might think of as the Kleisthenic revolution in Athenian politics: of his work as a lawgiver.

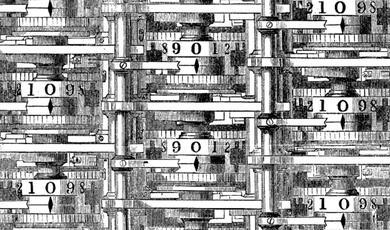

Ostracism was a mechanism allowing for a vote of at least six thousand Athenians to result in exiling one of their fellow citizens for a period of ten years. It first of all involved an annual vote in the Assembly on whether or not an ostracism should be conducted. If that vote passed (which was infrequent), then each Athenian citizen was asked to write the name of a person to be ostracized on a fragment of pottery (known as an ostrakon: hence the name). As another one of the later Atthidographers described it:

Ostracism takes place as follows. Before the eighth prytany, [1] the people vote on whether it is necessary to hold an ostracism. [2] If it is necessary, the agora is fenced in with boards, leaving ten entrances, through which the people enter in their tribes, and deposit their sherds [ostraca] with the writing facing downwards. [3] The nine archons and the council oversee the process. [4] When the sherds have been counted to determine who has the most votes (which must be not less than 6,000), [5] then this person must, after settling his personal commitments, leave the city within ten days, for a period of ten years (this was later reduced to five years). He is allowed to receive income from his possessions, but he must not come nearer [to Athens] than Geraestum, the headland on [the coast of] Euboea. (Philoch. Frag. 79b)[22]

A successful vote to ostracize someone could in principle happen for any reason. Indeed, there is a famous story about the general Aristides, a generation later, encountering a fellow Athenian writing his name on an ostrakon on grounds that he was simply tired of hearing Aristides endlessly called ‘the Just’ (and indeed Aristides was duly ostracized, in 482 BCE). But scholars have concluded that its principal function—and probably the major motivation for the establishment of the institution by Kleisthenes’ proposal in the first place—was to warn elites that any aspirations to tyranny or undue power were being watched and could be checked.[23] While to many later eyes, such as those of the post-French Revolutionary liberal author Benjamin Constant, this institution would appear strikingly illiberal, in the symbolic political economy of ancient Athens, it was a less punitive way to protect popular institutions from the threat that tyranny might recur.

It is interesting to note that Kleisthenes may have had personal reason, even perhaps personal temptation, to rule out in proposing this reform. His mother was not Athenian; she was the daughter of someone named Kleisthenes of the polis of Sicyon, who had in fact been in power there as its tyrant from c.600-570 BCE. So our Kleisthenes, the Athenian grandson of a foreign tyrant, might well have chosen to try to consolidate his own power in Athens and rule as the new Peisistratos.[24] This casts a particular light on his introduction of ostracism as a mechanism to keep future potential tyrants out. Indeed, as one of the later Atthidographers (local historians of Athens) recorded of the first person to have been actually ostracized, in 488/7, one Hipparkhos (not the son of Peisistratos, but someone else):

‘…Androtion in (book) two says that he was a relative of Peisistratos, the tyrant, and (that he) was the first to be ostracized, since the law regarding ostracism had then for the first time[25] been established on account of the suspicion of the supporters of Peisistratos, because while being a demagogue and general (strategos) he had ruled as a tyrant’.[26]

Having succeeded in moving from tyranny to (what in the fifth century would come to be called) democracy, the Athenians were all too well aware of the possibility of what today we are having to reckon with as democratic backsliding. In their view, popular power required continuing vigilance against the recurrence of tyranny.

© Professor Melissa Lane 2025

Footnotes

[1] In particular, see Melissa Lane, ‘Writing Laws: Hammurabi to Solon’, delivered on 23 January 2025 (https://www.gresham.ac.uk/watch-now/writing-laws), and ‘Ancient Greek Ideas of Justice, delivered on 11 January 2024 (https://www.gresham.ac.uk/watch-now/greek-justice).

[2] Greg Anderson, ‘Before Turannoi Were Tyrants: Rethinking a Chapter of Early Greek History’, Classical Antiquity 24 (2005): 173–222.

[3] Quotations from Herodotus’ Histories are from Robert B. Strassler (ed.) The Landmark Herodotus: The Histories, trans. Andrea L. Purvis (NY: Pantheon Books, 2007).

[4] Quotations from the AP, which is sometimes credited to Aristotle but sometimes to unnamed author(s) within his school, are taken from Aristotle, The Politics, and the Constitution of Athens, trans. Stephen Everson, rev. student ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996). In his commentary on the Greek text, P.J. Rhodes explains: ‘No one would now deny that A.P. is the Ἀθηναίων Πολιτεία from the collection of πολιτεῖαι attributed in the ancient world to Aristotle, that it was written in the 330's and 320's when Aristotle was in Athens, and that it is a product of the Aristotelian school; but it continues to be disputed whether Aristotle wrote the work himself or entrusted it to a pupil’, concluding: 'On the evidence which we have, Aristotle could have written this work himself, but I do not believe he did.That does not diminish the interest and importance of [the work]’: Rhodes, A Commentary on the Aristotelian Athenaion Politeia, rev. edn (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020), 61, 63 respectively.

[5] Later the Spartans would regret what they had done and try to get Hippias restored to power, but the Athenian assembly would reject that proposal (Hdt. 5.91-93).

[6] Josiah Ober, ‘“I Besieged that Man”: Democracy’s Revolutionary Start’, in Kurt A. Raaflaub, Josiah Ober and Robert W. Wallace, Origins of Democracy in Ancient Greece (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 84-104, at 84. This is only one of Ober’s multiple publications on this issue, which have been variously supported and criticized by other scholars; for an overview of the debate before and since Ober’s work, see Arnaud Macé and Paulin Ismard, La cité et le nombre: Clisthène d’Athènes, l’arithmétique et l’avènement de la démocratie (Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 2024), 35 n.1.

[7] See Ober, ‘“I Besieged that Man”’.

[8] This dimension of Rousseau’s thought is discussed by Judith N. Shklar, Men and Citizens: A Study of Rousseau’s Social Theory (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969).

[9] This is observed briefly by P.J. Rhodes, Atthis: the Ancient Histories of Athens (Heidelberg: Verlag Antike, 2014), 28: ‘it seems that in fact…[the] trittyes, “thirds” of tribes, were not each wholly in one of the three regions of Attica, and the statement that they should be is most easily explained as reflecting a plan which was not carried out exactly as had been intended’.

[10] For the idea of legibility to a top-down state, see James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed, 2nd edn (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999).

[11] Among them, the influential study, first published in French in 1964 and later revised and translated as Pierre Lévêque and Pierre Vidal-Naquet. Cleisthenes the Athenian: An Essay on the Representation of Space and Time in Greek Political Thought from the End of the Sixth Century to the Death of Plato, trans. David Ames Curtis (Atlantic Highlands, N.J.: Humanities Press International, 1996).

[12] Ismard and Macé, La cité et le nombre, on which I have also drawn (with the authors’ kind permission) for some of the diagrams included in the PowerPoint presentation of this lecture.

[13] Again, this is a topic that Josiah Ober has addressed in a series of important works, including the more general study of the theme in Ober, Democracy and Knowledge: Innovation and Learning in Classical Athens. Princeton University Press, 2008.

[14] AP 21.4 states the intention.

[15] Rhodes, Atthis, 28.

[16] As opposed to a recent biography of Plato by Robin Waterfield in which Plato is styled in the title as ‘Plato of Athens’, though there is otherwise much of interest in this work: see Waterfield, Plato of Athens: A Life in Philosophy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2023).

[17] Brock, ‘Civic and Local Identities’,15.

[18] See https://www.ch.ch/en/foreign-nationals-in-switzerland/naturalisation/#what-is-naturalisation, last checked on 12 October 2025.

[19] See Steven Lukes, Power: A Radical View, 2nd edn (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), for whom the third and most radical form of power includes, in effect, the ability to keep things from even surfacing as potential agenda items in the first place.

[20] Peter Krentz, Appendix A: The Athenian Government, in Strassler (ed.) The Landmark Herodotus, 723-7, at 726.

[21] Melissa Lane, ‘Lawgivers in Modern Revolutions’, delivered on 5 June 2025 (https://www.gresham.ac.uk/watch-now/lawgivers-modern-revolutions).

[22] Nicholas F. Jones, ‘Philochoros of Athens’, in Brill’s New Jacoby, ed. Ian Worthington (2016) (referring to FGrH 328 F30). I owe this reference, and other research assistance for this lecture, to Emily ‘Sal’ Salamanca; see Emily Salamanca, ‘Pruning of the People: Ostracism and the Transformation of the Political Space in Ancient Athens’, Philosophies 8 (2023): 81.

[23] Sara Forsdyke, ‘Exile, Ostracism and the Athenian Democracy’, Classical Antiquity 19 (2000): 232–63, and Forsdyke, Exile, Ostracism, and Democracy: The Politics of Expulsion in Ancient Greece (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005).

[24] Solon too had been expected by many to try to rule as a tyrant, a role that he disavowed in his poetry, though some scholars have questioned how far his role as lawgiver can be fully distinguished from such a role: for that criticism, see e.g. Johannes C. Bernhardt, A Failed Tyrant? Solon’s Place in Athenian History’, in From Homer to Solon: Continuity and Change in Archaic Greece, edited by Johannes C. Bernhardt and Mirko Canevaro (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2022), 414-461.

[25] As Sara Forsdyke has remarked, the claim that ostracism was established at this time that it was first used is ‘a mistake in the transmission of the text of Androtion’: see Forsdyke, ‘Exile, Ostracism and the Athenian Democracy’, Classical Antiquity 19 (2000) 232–63, at 253 n.84. Forsdyke there and in later work defends the case for considering ostracism to have been most likely introduced in 508/7 as part of Kleisthenes’ reform, though not all historians agree.

[26] Phillip Harding, The Story of Athens: The Fragments of the Local Chronicles of Attika (New York: Routledge, 2008), 98, source 109 (Androtion F6 = Harpokration, Lexikon s.v. Hipparkhos).

References and Further Reading

Primary Sources: Translations and Commentaries

Herodotus, Histories: in Strassler, Robert B. (ed.). The Landmark Herodotus: The Histories, trans. Andrea L. Purvis. NY: Pantheon Books, 2007. Includes: Peter Krentz, Appendix A: The Athenian Government, at 723-7.

Aristotle or Pseudo-Aristotle, The Constitution of Athens: in Aristotle, The Politics, and the Constitution of Athens, trans. Stephen Everson. Rev. student ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Harding, Phillip. The Story of Athens: The Fragments of the Local Chronicles of Attika. New York: Routledge, 2008.

Rhodes, P. J. A Commentary on the Aristotelian Athenaion Politeia. Revised edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020.

Secondary Sources

Anderson, Greg. ‘Before Turannoi Were Tyrants: Rethinking a Chapter of Early Greek History’. Classical Antiquity 24 (2005): 173–222.

Bernhardt, Johannes C. ‘A Failed Tyrant? Solon’s Place in Athenian History’, in From Homer to Solon: Continuity and Change in Archaic Greece, ed. Johannes C. Bernhardt and Mirko Canevaro, 414-461. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2022.

Brock, Roger. ‘Civic and Local Identities in Athenian Rhetoric’, in The Making of Identities in Athenian Oratory, ed.Jakub Filonik, Brenda Griffith-Williams, and Janek Kucharski, 15-31. London: Routledge, 2019.

Forsdyke, Sara. ‘Exile, Ostracism and the Athenian Democracy’. Classical Antiquity 19 (2000): 232–63.

Forsdyke, Sara. Exile, Ostracism, and Democracy: The Politics of Expulsion in Ancient Greece. Princeton University Press, 2005.

Ismard, Paulin, and Arnaud Macé. La cité et le nombre: Clisthène d’Athènes, l’arithmétique et l’avènement de la démocratie. Paris. Les Belles Lettres, 2024.

Lévêque, Pierre, and Pierre Vidal-Naquet. Cleisthenes the Athenian: An Essay on the Representation of Space and Time in Greek Political Thought from the End of the Sixth Century to the Death of Plato, trans. David Ames Curtis. Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Humanities Press International, 1996.

Lukes, Steven. Power: A Radical View. 2nd ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

Ober, Josiah. ‘“I Besieged that Man”: Democracy’s Revolutionary Start’, in Kurt A. Raaflaub, Josiah Ober, and Robert Wallace, Origins of Democracy in Ancient Greece, 83-104. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007.

Ober, Josiah. Democracy and Knowledge: Innovation and Learning in Classical Athens. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008.

Rhodes, P.J. Atthis: the Ancient Histories of Athens. Heidelberg: Verlag Antike, 2014.

Salamanca, Emily. ‘Pruning of the People: Ostracism and the Transformation of the Political Space in Ancient Athens’. Philosophies 8 (2023): 81.

Scott, James C. Seeing like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

Shklar, Judith N. Men and Citizens: A Study of Rousseau’s Social Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969.

Waterfield, Robin. Plato of Athens: A Life in Philosophy. New York: Oxford University Press, 2023.

Further Reading

Anderson, Greg. The Athenian Experiment: Building an Imagined Political Community in Ancient Attica, 508-490 B.C. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2003.

Fornara, Charles W. and Loren J. Samons II. Athens from Cleisthenes to Pericles. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1991.

Osborne, Robin. ‘When was the Athenian democratic revolution?’ in Rethinking Revolutions through Ancient Greece, edited by Simon Goldhill and Robin Osborne, 10-28. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Anderson, Greg. The Athenian Experiment: Building an Imagined Political Community in Ancient Attica, 508-490 B.C. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2003.

Fornara, Charles W. and Loren J. Samons II. Athens from Cleisthenes to Pericles. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1991.

Osborne, Robin. ‘When was the Athenian democratic revolution?’ in Rethinking Revolutions through Ancient Greece, edited by Simon Goldhill and Robin Osborne, 10-28. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Part of:

This event was on Thu, 16 Oct 2025

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham College plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login