2 October 2013

The Vietnam Informal Tribunal

Professor Sir Geoffrey Nice QC

In last year’s lectures I focused attention on international tribunals that seek to deal with crimes committed in conflict. I identified good things they do and shortcomings. One of several recurring concerns was that tribunals, however established, only ever try one side of a conflict and thus provide versions of ‘victors’ justice’.

I suggested that there may be more of a role for the citizen in the business of leaving records of conflicts than our national and international political leaders might like.

In this year I will deal, among other topics, with some particular instances in which the law, and lawyers may be seen as failing, sometimes unavoidably, the citizen caught up in armed conflict.

Intervention in Syria provided insight into how the world operates at moments of conflict crisis and how the law does or does not feature at such times. Discussion about legality – in particular whether it could be legal to intervene without a supporting UN Security Council Resolution – recognises that legality would only become relevant if the intervention is not a success or, at least, regarded as a success. Then – then only – are opponents of intervention able to beat governments with the legality argument.

Syria also reminds us how thin would seem the line between chemical weapons as defined by the OPCW and other weapons used by the great powers that somehow avoided that definition and how thin the line may be between conflict counted as unlawful when committed by countries without international power and very similar conduct in which they have themselves engaged.

In focusing on the Tribunal of Lord Russell into Vietnam I had expected to reach with ease a conclusion already in mind. But I didn’t. Other questions intervened. There is no point in reserving them all for later - they are these: Is it always a good thing to examine whether war crimes were committed? May it sometimes be better to do nothing? Is there any evidence that confessions due from governments arising from Vietnam conflict will serve any good? Are powerful countries like the USA entitled to different standards of review by the international community from those we now apply to countries like the former Yugoslavia or Rwanda or, perhaps, Syria?

The Syria conflict has had us drawn to the wonderland populated only by eternally wicked bogeymen who are forever bad and the potential for hypocrisy in those who wish to be seen as good. It is the way things are. Justice Jackson – whose words at Nuremberg were quoted at the start of the Russell Tribunal – said this:

‘If certain acts and violations of treaties are crimes, they are crimes whether the United States does them or whether Germany does them. We are not prepared to lay down a rule of criminal conduct against others which we would not be willing to have invoked against us.’

Yet Jackson also explained that in charging the Nazis with Crimes against Humanity a broader definition than the one the US employed could have exposed the US to the same pursuit [under law] for things it had done in the past.

We subject the actions of the bad in any conflict to whatever the law may seem to be at the time, not just in the printed law but also by other instruments of almost legal effect such as United Nations resolutions. But do we apply it to the powerful?

Maybe we should face the fact – no individual, body, state or collection of states will ever own up properly to what it has done wrong if it has the power to do otherwise. Is this the fundamental problem to be faced, and one that covers all areas of life and that neither parliament nor the courts nor any other system of inquiry has overcome.

The Vietnam War, a disaster, was the second of two Indo China conflicts that had a long history that started well after law making for the conduct of war was under way.

Bertrand Russell was born in 1872. He could not have recalled directly the Brussels Convention made two years later but everything else following that would have been in his active memory. It is sensible to attempt to cast his reactions to the Vietnam conflict that was to come at the end of his life in the setting of his own experience and (immense) knowledge.

An 1874 Brussels Convention prohibited the employment of poison or poisoned weapons and the use of arms, projectiles or material to cause unnecessary suffering.

An agreement signed at The Hague in 1899 prohibited the use of projectiles filled with poison gas.

The Hague Convention of 18 October 1907 denied belligerents unlimited choice for injuring an enemy and prohibited the use of arms deliberately destined to cause pointless suffering along with attacks on towns, villages, dwellings or undefended buildings.

Following World War I, a Vietnamese patriot named Nguyen That Thanh, then in his late twenties, went to the Paris Peace Conference where American President Woodrow Wilson had promised "self-determination" for nations. Thanh hoped to see Vietnam freed from French colonial rule. Like many other advocates of colonial independence who went to the Paris Peace Talks Thanh was ignored.

His name changed to Ho Chi Minh; he returned to Vietnam.

The 1925 Geneva Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or Other Gases, and Bacteriological Methods of Warfare banned the use of chemical and bacteriological (biological) weapons in war.

The 1928 Pact of Paris, known as the Briand-Kellogg Pact renounced the use of war and called for the peaceful settlement of disputes.

By World War II, Charter of Nuremberg Article 6 outlawed:

CRIMES AGAINST PEACE: Waging of a war of aggression, or a war in violation of international treaties, agreements or assurances.

WAR CRIMES including plunder of public or private property, wanton destruction of cities, towns or villages, or devastation not justified by military necessity.

CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY: Inhumane acts committed against any civilian population.

In 1945 following the surrender of Japan to Allied forces, Ho Chi Minh and his People's Congress created the National Liberation Committee of Vietnam - Vietminh - forming a provisional government and declaring Independence of Vietnam.

Fighting between French forces and their Việt Minh opponents dates from September 1945.

British Forces Landed in Saigon and helped return Vietnam to French authority but in 1946, negotiations between the French and the Vietminh failed and in December 1946 the First Indo China War started; it was to last 8 years until August 1954.

The French failed to wipe out the Vietminh and narrowly missed capturing Ho Chi Minh In 1949.

Early on, Ho Chi Minh told the French:

‘You can kill ten of my men for every one I kill of yours, but even at those odds, you will lose and I will win.’

The French pledged to assist in the building of a national anti-Communist army. The Chinese and Soviets offered weapons to the Vietminh. The United States sent $15 million dollars to the French for the war in Indochina with a military mission and military advisors.

The Geneva Convention of 2 August 1949 prohibited attacks on civilian hospitals and private and collective property not rendered absolutely necessary by the conduct of the operations.

In 1954 at Dienbienphu a force of 40,000 heavily armed Vietminh laid siege to the French garrison and thereby crushed the French. A peace conference was held in Geneva to work out the future of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia attended by Laos, Cambodia, France, the United States, the Soviet Union, Britain, and China. It marked the end of the First Indochina War.

US President Eisenhower coined the phrase "Domino Theory" Regarding Southeast Asia:

"You have a row of dominoes set up. You knock over the first one, and what will happen to the last one is the certainty that it will go over very quickly."

Eisenhower’s administration, fearing communism, instructed US delegates to observe the proceedings but to not sign the accords. However, under Chinese and Soviet pressure, the Vietminh reached a compromise with the French that divided the country temporarily in half at the 17th parallel. Vietminh forces were to withdraw to the north of this line while French forces would withdraw to the south. Each side agreed not to sign military alliances or permit foreign bases on Vietnamese soil and internationally supervised national elections were to be held in 1956 to unify the country.

The Geneva Accords were never fulfilled. The United States initiated a military buildup and replaced the French puppet Bao Dai with Ngo Dinh Diem, a Christian anticommunist. Diem, fearing that communist leader Ho Chi Minh would easily win an open election, instead held a rigged referendum to legitimize his dictatorship.

The French left Vietnam.

The failure of the Geneva Accords can be viewed in hindsight as a lost opportunity, as the United States became embroiled in the Second Indochina War, one of the most destructive conflicts in modern history that many historians mark as a key turning point in the decline of American hegemony.

The proxy war to come - fighting over a belief if it was not colonization by another route - was in the making. Looking back one can see how odd it was to allow a war to develop largely premised on fear of an economic model. Extreme economic models all have something good about them and probably all moderate or modulate over time. What better example could there be than the economies of China or Vietnam itself or the clear need of aggressive capitalism in democratic countries to find a new socialism suited to the age if they are to avoid their bankers and ever richer minorities being hanged from lampposts. But what would an intelligent being from another galaxy have said had it been unwise enough to visit such a dangerous place as the Earth if it then found that we had destroyed ourselves altogether in a nuclear battle started by concern about an economic model of life - and President Nixon considered the nuclear option to resolve Vietnam.

What was to come in deaths and horror overall we now know, although imprecisely (and statistics at best indicative)

195,000-430,000 South Vietnamese civilians died in the war.

50,000-65,000 North Vietnamese civilians died in the war.

The Phoenix counterinsurgency program executed by the CIA, United States special operations forces, and the Republic of Vietnam's security apparatus, killed 26,369 suspected National Liberation Front (NLF) operatives and informants.

American bombing in Cambodia killed at least 40,000 combatants and civilians.

The Army of the Republic of Vietnam lost between 171,331 and 220,357 men during the war.

US combat began in 1965. The number of US troops steadily increased until it reached a peak of 543,400 in April 1969. The total number of Americans who served in South Vietnam was 2.7 million. Of these, more than 58,000 died or remain missing, and 300,000 others were wounded. The US. government spent more than $140 billion on the war. The United States failed to achieve its objective of preserving an independent, noncommunist state in South Vietnam.

153,303 US service personnel wounded in action, 1,645 missing in action.

There were also tens of thousands of suicides after the North Vietnamese take-over.

One expert, Rummel, estimates that overall a minimum of 400,000 and a maximum of slightly less than 2.5 million people died of political violence from 1975-87 at the hands of Hanoi.

Contrast

WWI total deaths 17 million.

WWII total deaths 50-80 million.

Under the leadership of Pol Pot, the Khmer Rouge killed 1-3 million Cambodians in the killing fields, out of a population of around 8 million.

The Pathet Lao killed some 100,000 Hmong people in Laos.

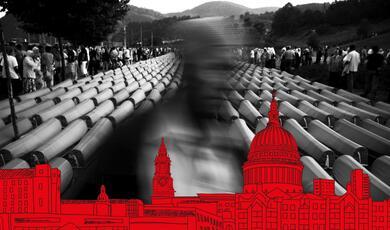

Balkan Wars of the 1990s saw about 200,000 deaths. Seven massacres were eventually confirmed by the American side as criminal. My Lai and My Khe claimed the largest number of victims with 420 and 90 respectively, and in five other places altogether about 100 civilians were executed.

18.2 million gallons of Agent Orange (Dioxin) was sprayed by the U.S. military over more than 10% of Southern Vietnam, as part of the U.S. herbicidal warfare program, Operation Ranch Hand, during the Vietnam War from 1961 to 1971. Vietnam's government claimed that 400,000 people were killed or maimed as a result of after effects, and that 500,000 children were born with birth defects.

NAPALM and AGENT ORANGE

The moral outrage expressed recently by worthy governments over chemical weapons used in Syria will have stimulated contemplation of Napalm and Agent Orange.

Napalm and Agent Orange caused immense suffering and attacked a country’s environment as well as its people – but are not within the OPCW definition of chemical weapon. As to what modern man may feel, I can hardly improve on how Sean Thomas expressed himself recently in the Daily Telegraph:

Technically speaking, napalm is “a mixture of naphthenic and aliphatic carboxylic acid”. Sounds awfully “chemical” to me… and…. has been liberally used by the US army to incinerate soldiers (and luckless civilians) in many recent wars, including Gulf War 1.

Agent Orange’s stated intention was to “defoliate” Vietnam, i.e, kill all the plant life so Viet Cong soldiers could not hide in forests, thus enabling America to napalm her enemies more easily.

Unsurprisingly, it turned out that Agent Orange, so effective in killing plant life, was not great for humankind, either. Tens of thousands of Vietnamese have died as a result of this poison and such is the evilness of the dioxin within Agent Orange, even today children in the third generation are being born with hideous deformities.

How did we do this to ourselves?

In 1956 the US started training South Vietnamese military.

In 1957 communist insurgency into South Vietnam led to the assassination of more than 400 South Vietnamese officials.

In 1958 terrorist bombings rocked Saigon and thirteen Americans working for MAAG and US Information Service were wounded.

In 1959 North Vietnam began infiltrating cadres and weapons into South Vietnam via the Ho Chi Minh Trail which will become a strategic target for future military attacks. Two US Servicemen became the first Americans to be killed by guerillas.

December 1960 United Nations resolution decided that all peoples have fundamental rights to national independence, to sovereignty, to respect of the integrity of their territory, and that breaches of these fundamental rights may be regarded as crimes against the national existence of a people.

In 1969 North Vietnam imposed Universal Military Conscription. Kennedy narrowly defeated Nixon for the presidency. Hanoi formed National Liberation Front for South Vietnam. Diem government dubbed them "Vietcong."

In 1961, although there was no formal declaration of war, President Kennedy made the decision to send over 2,000 military advisers to South Vietnam. This marked the beginning of twelve years of American military combat. Some of Kennedy's aides proposed a negotiated settlement in Vietnam similar to that which recognized Laos as a neutral country. Having just suffered international embarrassment in Cuba and Berlin, the president rejected compromise and chose to strengthen U.S. support of Saigon.

During a tour of Asian countries, Vice President Lyndon Johnson visited Diem in Saigon and assured him that he was crucial to US objectives in Vietnam and called him "the Churchill of Asia".

Bertand Russell, now in his late 80s, was an active member of the Campaign for Nuclear disarmament. He went to prison as a result (and when asked by a magistrate whether he would be of good behaviour said he wouldn’t!) He wrote this on the subject of civil disobedience:

‘… Kennedy and Macmillan and others both in the East and in the West pursue policies which will probably lead to killing not only all the Jews but all the rest of us too. They are much more wicked than Hitler and this idea of weapons of mass extermination is utterly and absolutely horrible and it is a thing which no man with one spark of humanity can tolerate and I will not pretend to obey a government which is organising the massacre of the whole of mankind. I will do anything I can to oppose such Governments in any non-violent way that seems likely to be fruitful…….’

In 1962 US Air Force began using Agent Orange - a defoliant that came in metal orange containers - to expose roads and trails used by Vietcong forces.

1963 President Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas and the problem of how to proceed in Vietnam fell to his vice president, Lyndon Johnson. Four days after Kennedy's death, Johnson, now president, reaffirmed that the U.S. goal was to assist South Vietnam in its "contest against the externally directed and supported communist conspiracy."

Tensions between Buddhists and the Diem government are further strained as Diem, a Catholic, removed Buddhists from several key government positions and replaced them with Catholics. Buddhist monks start setting themselves on fire in public places.

With tacit approval of the United States, operatives within the South Vietnamese military overthrew Diem. He and his brother Nhu were shot and killed in the aftermath.

Throughout his administration, Johnson insisted that the only possible negotiated settlement of the conflict would be one in which North Vietnam recognized the legitimacy of South Vietnam's government. Without such recognition, the United States would continue to provide Saigon as much help as it needed to survive.

On May 12, twelve young men in New York publicly burned their draft cards to protest the war.

Gen. Curtis LeMay, May 1964:

‘Tell the Vietnamese they've got to draw in their horns or we're going to bomb them back into the Stone Age.’

The White House had prepared the text of a congressional resolution authorising the president to use armed force to protect U.S. forces and to deter further aggression from North Vietnam. On August 2, three North Vietnamese PT boats allegedly fired torpedoes at the USS Maddox, a destroyer located in the international waters of the Tonkin Gulf, some thirty miles off the coast of North Vietnam. A second, even more highly disputed, attack was alleged to have taken place on August 4. On 7 August 1964, Johnson secured almost unanimous consent from Congress (414-0 in the House; 88-2 in the Senate) for his Gulf of Tonkin Resolution that authorised him to "take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression". The Resolution allowed Johnson to wage all out war against North Vietnam without ever securing a formal Declaration of War from Congress and became the principal legislative basis for all subsequent military deployment in Southeast Asia.

By the end of 1964 U.S. personnel in South Vietnam exceeded 23,000. Increasingly, however, the U.S. effort focused on the North.

Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara, Secretary of State Dean Rusk, and other key White House aides remained convinced that the assault on South Vietnam originated in the ambitious designs of Hanoi backed by Moscow and Beijing.

In December 1964, Joan Baez led six hundred people in an antiwar demonstration in San Francisco.

Using as a pretext a Vietcong attack on 7 February 1965 at Pleiku that killed eight American soldiers, Johnson ordered retaliatory bombing north of the Demilitarized Zone along the 17th parallel that divided North and South Vietnam, by ‘Rolling Thunder’, a gradually intensifying air bombardment of military bases, supply depots, and infiltration routes in North Vietnam. The bombing continued for three years.

The first American combat troops, the 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade, arrived in Vietnam to defend the US airfield at Danang.

US Troop levels topped 200,000.

"Teach-ins" at colleges and universities - featuring seminars, rallies and speeches becomes widespread. In May, a nationally broadcast "teach-in" reaches students and faculty at over 100 campuses.

In 1965, U.S. aircraft flew 25,000 sorties against North Vietnam, and that number grew to 79,000 in 1966 and 108,000 in 1967. In 1967 annual bombing tonnage reached almost a quarter million. Targets expanded to include the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos and factories, farms, and railroads in North Vietnam.

The Vietcong continued to inflict heavy casualties on the ARVN, and the political situation in Saigon grew worse. To stave off defeat, the JCS endorsed Westmoreland's request for 150,000 U.S. troops to take the ground offensive in the South. When McNamara concurred, Johnson announced that 50,000 U.S. troops would go to South Vietnam immediately. By the end of the year, there were 184,300 U.S. personnel in the South.

The JCS wanted to mobilise the reserves and the National Guard, and McNamara proposed levying war taxes. The president wanted to avoid giving congressional conservatives an opportunity to use mobilization to block his domestic agenda. Consequently he relied on other means. Monthly draft calls increased from 17,000 to 35,000 to meet manpower needs, and deficit spending, with its inherent inflationary impact, funded the escalation.

With U.S. bombs pounding North Vietnam, Westmoreland turned America’s massive firepower on the southern insurgents. But risks of a wider war with China and the Soviet Union meant that the United States would not go all out to annihilate North Vietnam.

Thus, Westmoreland chose a strategy of attrition in the South. Using mobility and powerful weapons that could limit U.S. casualties while exhausting the enemy.

In 1965 Hanoi began deploying into the South increasing units of the regular North Vietnamese Army (NVA), or People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN), as it was called. Through much of November, in the Battle of the Ia Drang Valley, U.S. and North Vietnamese forces engaged each other in heavy combat for the first time. Huge B-52 strategic bombers attacked enemy positions. "Search and destroy" tactics seemed to achieve the attrition strategy. However the American air cavalry left the battlefield soon after the PAVN, so control of territory seemed not to be the U.S. military objective.

On March 24, Professors against the war at the University of Michigan organised a protest attended by 2,500 participants. This model was to be repeated at 35 campuses across the country.

On March 16, Alice Herz, a 82-year-old pacifist, set herself on fire in the first known act of self-immolation to protest the Vietnam War. In March there were anti-war marches in Washington, D.C. of about 25,000 protesters.

Draft-card burnings took place at University of California, Berkeley at student demonstrations in May organized by a new anti-war group, the Vietnam Day Committee.

In May – First anti-Vietnam War demonstration in London was staged outside the U.S. embassy.

By mid-October, the anti-war movement had become a national and even global phenomenon, as anti-war protests drawing 100,000 were held simultaneously in as many as 80 major cities around the US, London, Paris, and Rome.

On November 2, Norman Morrison, a 31-year-old pacifist, set himself on fire below the third-floor window of Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara at the Pentagon, emulating the actions of the Vietnamese monk Thích Quảng Đức.

On November 27 Benjamin Spock, among others, spoke at an anti-war rally of about 30,000 in Washington, D.C., in the largest demonstration to date. Parallel protests occurred elsewhere around the nation. On that same day, President Johnson announced a significant escalation of U.S. involvement in Indochina, from 120,000 to 400,000 troops.

The First Vietnam legal case concerned US Constitutional issues not whether the conflict was itself unlawful. In United States v. Mitchell in December 1965 Mitchell, facing a criminal prosecution, claimed that conscription was unconstitutional because Congress had not declared war, that the Government was committing war crimes in Vietnam, and that American military activity in Vietnam violated international law and treaties to which the United States was signatory. Many of Mitchell's claims were presented time and again, in one form or another, to federal courts throughout the Vietnam War. Mitchell's motion to dismiss the indictment was denied and he was convicted of refusing induction on grounds inter alia "These contentions are wholly without merit and have been repeatedly and consistently rejected by the courts of the United States." The court additionally held that Mitchell lacked standing to assert unconstitutionality until he was inducted and ordered to Vietnam. In United States v. Mitchell (December 1966) at a second appeal the court upheld the exclusion of evidence that American military operations in Vietnam violated treaties to which the United States was signatory and thus rendered conscription unlawful as an adjunct to illegal military activity because the constitutional power of Congress to provide armed forces by conscription is a "matter quite distinct" from the use of such forces by the President and Congress.

The Supreme Court, with only Justice Douglas dissenting, denied review in Mitchell. Because Mitchell invoked the Treaty of London, which declares that a war of aggression is a crime imposing individual responsibility on combatants, Justice Douglas believed that Mitchell's conviction and proffered defence presented issues that should be answered by granting review.

In 1966 the ‘Juridical Memorandum on the Legality of the Participation of the United States in the Defence of Vietnam’, submitted to the Senate Foreign Affairs Committee on 4 March 1966 argued that the American intervention in Vietnam merely constituted aid to the Saigon government against aggression from the North.

President Johnson promised to continue to help South Vietnam fend off aggression from the North, Veterans from World Wars I and II, along with Veterans from the Korean War staged a protest rally in New York City. Discharge and separation papers are burned in protest of US involvement in Vietnam.

The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) issued a report claiming that the US military draft places "a heavy discriminatory burden on minority groups and the poor”.

I dare say it did. Was it an appropriate priority to consider the internal demographic unfairness of risk of loss of life in this way against the extraordinary loss of life being caused in Vietnam, the legality of which the courts declined to investigate?

On March 26, anti-war demonstrations were held around the country and the world, with 20,000 taking part in New York City.

Protests, strikes and sit-ins continued at Berkeley and across other campuses throughout the year.

Part way through this year – in May 1966 – Bertrand Russell addressed the first Meeting of Members of the War Crimes Tribunal, London, 13 November 1966:

‘Somehow, it was widely felt, there had to be criteria against which such actions could be judged, and according to which Nazi crimes could be condemned. Many felt it was morally necessary to record the full horror. It was hoped that a legal method could be devised, capable of coming to terms with the magnitude of Nazi crimes. These ill-defined but deeply felt sentiments surrounded the Nuremberg Tribunal…

We are free to conduct a solemn and historic investigation, uncompelled by reasons of state or other such obligations. Why is this war being fought in Vietnam? In whose interest is it being waged? We have, I am certain, an obligation to study these questions and to pronounce on them, after thorough investigation, for in doing so we can assist mankind in understanding why a small agrarian people have endured for more than twelve years the assault of the largest industrial power on earth, possessing the most developed and cruel military capacity …

I believe that we are justified in concluding that it is necessary to convene a solemn Tribunal, composed of men eminent not through their power, but through their intellectual and moral contribution to what we optimistically call ‘human civilization…

We must record the truth in Vietnam. We must pass judgement on what we find to be the truth. We must warn of the consequences of this truth. We must, moreover, reject the view that only indifferent men are impartial men. We must repudiate the degenerate conception of individual intelligence, which confuses open minds with empty ones…

I hope that this Tribunal will select men who respect the truth and whose life’s work bears witness to that respect. Such men will have feelings about the prima facie evidence of which I speak. No man unacquainted with this evidence through indifference has any claim to judge it…

In my own experience I cannot discover a situation quite comparable. I cannot recall a people so tormented, yet so devoid of the failings of their tormentors. I do not know any other conflict in which the disparity in physical power was so vast. I have no memory of any people so enduring, or of any nation with a spirit of resistance so unquenchable…

Our mandate is to uncover and tell all. My conviction is that no greater tribute can be provided than an offer of the truth, born of intense and unyielding inquiry…

May this Tribunal prevent the crime of silence.’

Looking back who would now deny the humanity and wisdom of what he said? Who might not now wish that such elevated thinking could be applied to present problems and not the uncertain and crude bargaining of weapon against weapon heard so often in battles fought out on someone else’s land.

But Russell’ elevated thinking would have to take account of the law.

What, according to modern scholarship, was the applicable law? It included:

Grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions of 1949 that outlawed willful killing, willfully causing great suffering or serious injury to body or health, extensive destruction and appropriation of property, not justified by military war.

Violations shall include: Employment of poisonous weapons or other weapons calculated to cause unnecessary suffering; wanton destruction of cities, towns or villages, or devastation not justified by military necessity.

With this (and more) law in their minds the Tribunal consisted of intellectuals of various kinds – including (my choice of the famous): Bertrand Russell, Jean-Paul Sartre, A.J. Ayer, James Baldwin, Simone de Beauvoir, Stokely Carmichael, Lawrence Daly (General Secretary, National Union of Mineworkers) and Tariq Ali.

The Aims of the Tribunal were agreed at the Constituting Session, London, 15 November 1966.

‘We constitute ourselves a Tribunal which, even if it has not the power to impose sanctions, will have to answer, amongst others, the following questions:

1. Has the United States Government (and the Governments of Australia, New Zealand and South Korea) committed acts of aggression according to international law?

2. Has the American army made use of or experimented with new weapons or weapons forbidden by the laws of war?

3. Has there been bombardment of targets of a purely civilian character, for example hospitals, schools, sanatoria, dams, etc., and on what scale has this occurred?

4. Have Vietnamese prisoners been subjected to inhuman treatment forbidden by the laws of war and, in particular, to torture or mutilation? Have there been unjustified reprisals against the civilian population, in particular, execution of hostages?

5. Have forced labour camps been created, has there been deportation of the population or other acts tending to the extermination of the population and which can be characterized juridically as acts of genocide?’

By the year's end the U.S. ground force level "in country" reached 385,000. Although the "body count"- the estimated number of enemy killed - mounted, attrition was not changing the political equation in South Vietnam. The NLF continued to exercise more effective control in many areas than did the government, and Vietcong guerrillas, who often disappeared when U.S. forces entered an area, quickly reappeared when the Americans left.

Heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali declared himself a conscientious objector and refused to go to war. The governor of Illinois, Otto Kerner, Jr., called Ali "disgusting" and the governor of Maine, John H. Reed, said that Ali "should be held in utter contempt by every patriotic American." In 1967 Ali was sentenced to 5 years in prison for draft evasion, but his conviction was later overturned on appeal. In addition, he was stripped of his title and banned from professional boxing for more than three years.

On April 14, 1967 Civil rights leader Martin Luther King claimed that America had rejected Ho Chi Minh's revolutionary government which he said was seeking Vietnamese self-determination. Ho's government was, said King, "a government that had been established not by China (for whom the Vietnamese have no great love) but by clearly indigenous forces that included some Communists. For the peasants this new government meant real land reform, one of the most important needs in their lives."

Other Vietnam legal cases in the USA were much like the Mitchell case.

In Luftig v. McNamara (February 1967) another draft case held that no question is "less suited" for the federal courts than "overseeing the conduct of foreign policy on the use and disposition of military power," which are matters committed exclusively to Congress and the President, The Supreme Court declined review.

In Mora v. McNamara (February 1967), a case apparently similar to Luftig the Supreme Court declined review though not without dissents from Justices Stewart and Douglas. Mora and his fellow plaintiff draftees, ordered to a replacement station for shipment to Vietnam, filed suit to invalidate their orders for the reason that American military activity in Vietnam was "illegal." Justice Stewart observed that Mora presented "questions of great magnitude." Is American military activity in Vietnam a "war" within the meaning of the constitutional text granting to Congress the power to declare war? If so, may the President order these draftees to participate in this "war" when Congress has not declared war? Of what relevance are present treaty obligations of the United States? Of what relevance is the Tonkin Gulf Resolution? Are Vietnam military operations within the terms of the resolution? If so, does the resolution represent an impermissible delegation of congressional war power to the unlimited discretion of the President? Recognising that consideration of these "large and deeply troubling" questions depends on the threshold issue of justiciability, and disclaiming any view on the question of justiciability or the merits of the constitutional claims, Justice Stewart declared that the Court should nevertheless grant review: "We cannot make these problems go away simply by refusing to hear the case of three obscure Army privates."

At least some recognition of a legal duty to judge, apparently not recognised by the dissenting Justices’ colleagues.

In January 1967 a major ground war effort dubbed Operation Cedar Falls with some 16,000 US and 14,000 South Vietnamese troops set out to destroy Vietcong operations and supply sites near Saigon. A massive system of tunnels is discovered in an area called the Iron Triangle, an apparent headquarters for Vietcong personnel.

March 25 – Civil rights leader Martin Luther King led a march of 5,000 against the war in Chicago, Illinois.

On 15 April, 400,000 people organised by the Spring Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam marched from Central Park to the UN building in New York City to protest the war, where they were addressed by critics of the war such as Benjamin Spock, Martin Luther King, James Bevel, Harry Belafonte, and Jan Barry Crumb, a veteran of the war. On the same date 100,000, including Coretta Scott King, marched in San Francisco.

Martin Luther King called the US "the greatest purveyor of violence in the world," and later encouraged draft evasion.

University of Wisconsin students successfully demanded that corporate recruiters for Dow Chemical - producers of napalm - not be allowed on campus.

Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, appearing before a Senate subcommittee, testified that US bombing raids against North Vietnam had not achieved their objectives. McNamara maintained that movement of supplies to South Vietnam has not been reduced, and neither the economy nor the morale of the North Vietnamese had been broken.

The first session of the tribunal was held at Stockholm, 2-10 may 1967. There were opening statements, a limited number of eye witness accounts, expert reports (bombing, fragmentation bombs, significance of bombing dykes in Vietnam etc) and reports of those who had made specific inquiries for the Tribunal. It was not, thus, a ‘proper’ court with evidence and cross examination. That itself raises issues. Should we be bound only to attend to evidence presented in the way acceptable to western criminal courts? I have presumed to doubt this. I raised with the judges in The Hague the probability or certainty that they could reach the same conclusions they achieved after years of slow evidence by reading a range of well informed books and journalism coupled with the live evidence that they might require. The tortoise of the common law criminal trial serves the bank balances of the lawyers and judges; it is less clear whether it really provides for better verdicts. It does, it is true, lay down a record of evidence meticulously chronicled and that record may serve later purposes. But does it equal the decision making process that may be achieved by intelligent well informed men and women making conscientious inquiry. I am not so sure.

The evidence presented to the Tribunal merits detailed attention. Here are three samples:

Gabriel Kolko, an American ‘leftist’ historian.

Vietnam is essentially an American intervention against a nationalist, revolutionary agrarian movement which embodies social elements in incipient and similar forms of development in numerous other Third World nations. It is in no sense a civil war, with the United States supporting one local faction against another, but an effort to preserve a mode of traditional colonialism via a minute, historically opportunistic comprador class in Saigon. For the United States to fail in Vietnam would be to make the point that even the massive intervention of the most powerful nation in the history of the world was insufficient to stem profoundly popular social and national revolutions throughout the world. Such a revelation of American weaknesses would be tantamount to a demotion of the United States from its present role as the world’s dominant super-power.

Do Van Ngoc nine years old, from the village of Vinh Tuy.

“16 June 1966, I was looking after the oxen with my two friends, named Ha Khec and Do Van Giau, when three American planes appeared from over the sea and dropped bombs on the place where we were. The bombs exploded and the flames reached the bodies of all three of us, causing us very serious burns. Since we could no longer bear the heat, we jumped into a flooded rice field; then the flames were put out and the heat lessened, but when we emerged from the water the flames broke out again on our bodies.

Now the burns are scarred, but I still have itching and burning sensations. On my right hand, the thumb is stuck to the other fingers; large scars remain on my stomach and my thighs.

That day the American bombs still set fire to the homes of our family and our neighbours. To my knowledge, apart from the three of us, Mr Du's family, while having their meal, lost six of its eight members, burned by bombs.”

Henrick Forss — Examinations of Victims of US Bombs

This is a simple report. It covers only a very small part of a subject of immense proportions: victims from bombings in North Vietnam.

“…One [victim] was Nguyen Thi Nam, a twenty-four-year-old woman from Nam Dinh…. She was pregnant in her ninth month. Fragments of the CBU penetrated the intestines and the uterus, killing the foetus which had to be removed surgically…… It is uncertain whether she can have any more children.”

Sartre’s Summary and Verdict of the Stockholm Session included:

‘Having heard the qualified representatives of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam and noted the official refusal of the government of the United States of America to make known its point of view, and this despite the various appeals addressed to it…

Having heard the various reporters, the experts, numerous witnesses, including members of the investigating teams which it had itself sent to Vietnam, as well as Vietnamese victims of the war…

Having examined several written, photographic and cinematographic documents, together with numerous exhibits... considers itself able to take the following decisions.

On the first question:

Reciting the Briand-Kellogg Pact, Article 6 of the Statute of Nuremberg, Article 2 of the United Nations Charter and the United Nations resolution of December 1960 referred to above he observed that the accession to independence and to national existence of the people of Vietnam dated back to 2 September 1945 but was called in question by the old colonial power. The war of national liberation – ie the First Indochina War - then embarked upon ended with the victory of the Vietnam army.

The Geneva Agreements of 20 and 21 July 1954… recognized the guarantees, independence, unity and territorial integrity of Vietnam. Although a line of demarcation divided the country into two parts on a level with the 17th parallel, it was expressly stipulated that as the essential aim of this division was to settle military questions, it was of a provisional nature ‘and could in no way be interpreted as constituting a political or territorial settlement. The Geneva Agreements stipulated that general elections should take place over the whole of the country in July 1956 under the supervision of an international commission, and that consultations on this subject were to take place between the competent representatives of the two zones as from July 1955.

The Agreements specifically excluded all reprisals or discrimination against persons and organizations by reason of their activities during the previous hostilities (Article 14 of the Armistice Agreement). They formally prohibited the introduction of fresh troops, of military personnel, fresh arms and munitions, as well as the installation of military bases) and the inclusion of Vietnam in military alliances, this applying to the two zones.

This state of law, intended to create a peaceful situation in Vietnam, was replaced by a state of war in consequence of successive violations and the responsibility for the passage to a state of war lies with the government of the United States of America.

It transpires from the information of a historical and diplomatic nature that has been brought to the knowledge of the Tribunal that numerous proofs exist of the American intention prior to 1954 to dominate Vietnam; that the Diem government was set up in Saigon by American agents several weeks before the conclusion of the Geneva Agreements;

that the Saigon authorities, subservient to the United States, systematically violated the provisions of the Geneva Agreements which prohibited reprisals, as has been established on several occasions by the International Control Commission; That in defiance of the Geneva Agreements, the United States has, since 1954, introduced into Vietnam increasing quantities of military equipment and personnel and has set up bases there.

The Tribunal has made a point of examining scrupulously the arguments put forward in American official documents to justify the legality of their intervention in Vietnam. Special attention has been paid to the document entitled: ‘Juridical Memorandum on the Legality of the Participation of the United States in the Defence of Vietnam’, which document was submitted to the Senate Foreign Affairs Committee on 4 March 1966. The main argument formulated by this text consists in claiming that the American intervention in Vietnam merely constitutes aid to the Saigon government against aggression from the North.

Such an argument is untenable both in law and in fact.

In law, it is hardly necessary to recall that Vietnam constitutes a single nation which cannot be seen as an aggressor against itself. The fact is that no proof of this alleged aggression has ever been produced. The figures stated of infiltration of personnel from the North into the South, often contradictory, mixing up armed men and unarmed men, are thoroughly disputable and could in no case justify the plea of legitimate defence provided for in Article 51 of the United Nations Charter, an Article, moreover, none of the other conditions of which is complied with.

From the foregoing it follows that the United States bears the responsibility for the use of force in Vietnam and that it has in consequence committed a crime of aggression against that country, a crime against peace.

It has therefore violated the provisions of International Law outlawing the use of force in international relations, in particular the Pact of Paris of 1928, the so-called Briand-Kellogg Pact, of which it was the author… This violation of the general principles has been accompanied by violation of the special agreements relating to the territory in question, Vietnam - that is to say, the Geneva Agreements of July 1954.

The United States has furthermore committed a crime against the fundamental rights of the people of Vietnam.

It should be added that states such as South Korea, Australia and New Zealand, which have in one form or another provided aid to the American aggression, have rendered themselves accomplices.

The Tribunal… considers that the forces of the United States and those of the governments subordinate to it at Bangkok and Saigon are engaging in continuous and serious acts of aggression against the kingdom of Cambodia.

On the second question:

The Tribunal has been convinced that the aerial, naval and land bombardments of civil targets is of a massive, systematic and deliberate nature.

According to a report of American origin, the aircraft stationed at a single base in Thailand alone utilize 300,000 metres of film every month to photograph Vietnam. If it is borne in mind on the one hand that most of the aircraft are equipped with automatic firing devices and, on the other hand, that the aircraft return persistently and furiously to the same targets, which are sometimes already almost completely destroyed, no doubt is possible as to the deliberate intention to strike the targets in question.

Besides the aerial bombardments, intense pounding by the artillery of the US 7th Fleet is progressively ravaging the coastal zones.

All of the witnesses heard, in particular the members of the investigating teams, have confirmed that the greater part of the civilian targets (hospitals, sanatoria, schools, churches, pagodas) are very obvious and very clearly distinguishable from the rest of the Vietnam countryside.

So far as hospitals are concerned, out of ninety-five establishments mentioned as destroyed by the Vietnamese Commission of Inquiry into War Crimes, thirty-four have been verified by the Tribunal’s investigating teams, i.e. thirty-six per cent. The great value of these samplings lie in their dispersion, since the thirty-four hospitals checked relate to eight provinces out of the twelve involved in the bombardments.

Apart from the extensive private evidence submitted to it, the Tribunal has heard general reports on the distribution of the various categories of civilian targets: hospitals, schools, places of worship (pagodas and churches) and dams, as well as of the bombardment of the civilian population of urban centres and in the countryside.

The Tribunal ascertained the vital importance to the people of {182} Vietnam of the dams and other hydraulic works, and the grave danger of famine to which the civilian populations were exposed by the attempted destruction by the American forces.

The Tribunal has received all necessary information in the diversity and power of the engines of war employed against the Democratic Republic of Vietnam and the circumstances of their utilization (high-explosive bombs, napalm, phosphorus and fragmentation bombs, etc.). Seriously injured victims of napalm bombs have appeared before it and medical reports on these mutilated people have been provided. Its attention in particular has been drawn to the massive use of various kinds of anti-personnel bombs of the fragmentation type…. in Vietnamese parlance, pellet bombs. These devices, obviously intended to strike defenceless populations, have the following characteristics.

A single mother bomb can cause the dispersion of nearly 100,000 pellets; these pellets can cause no serious damage to buildings or plant or to protected military personnel (for example, civil-defence workers behind their sandbags). They are therefore intended solely to reach the greatest number of persons in the civilian population.

The Tribunal has had medical experts study the consequences of attacks with these pellets. The path of the particles through the body is long and irregular and produces, apart from cases of death, multiple and various internal injuries.

Citing The Hague Convention No. 4 of 18 October 1907, Article 6 of the Statutes of the Tribunal of Nuremberg, the Geneva Convention of 2 August 1949 he observed that the government of the United States cannot override such Treaties, to which it has subscribed, whilst its own constitution (Article 6, para. 2) gives them preeminence over domestic law. Furthermore, the Official Manual entitled The Law of Land Warfare refers to all of the foregoing provisions as being obligatory for all members of the American army.

In consequence, the Tribunal considers that in subjecting the civilian population and civilian targets of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam to intensive and systematic bombardment, the United States of America has committed a war crime.

Apart from condemnation of this war crime, the Tribunal makes a point of declaring that fragmentation bombs of the CBU type, which have no other purpose than to injure to the maximum the civilian population, must be regarded as arms prohibited by the laws and customs of war.

Meeting with the resistance of a people who intended to ‘exercise peacefully and freely its right to full independence and to the integrity of its territory’ (United Nations resolution of 14 December 1960), the government of the United States of America has given these war crimes, through their extent and frequency, the character of crimes against humanity (Article 6 of the Statute of Nuremberg).

These crimes cannot be regarded merely as a consequence of a war of aggression, whose prosecution is determined by them.

Because of their systematic employment with the object of destroying the fundamental rights of the people of Vietnam, their unity and their wish for peace, the crimes against humanity of which the government of the United States of America has rendered itself guilty, become a fundamental constituent part of the crime of aggression, a supreme crime which embraces all the others according to the Nuremberg verdict.’

Verdict of the Tribunal

Has the Government of the United States committed acts of aggression against Vietnam under the terms of international law?

Yes (unanimously).

Has there been, and if so, on what scale, bombardment of purely civilian targets, for example, hospitals, schools, medical establishments, dams, etc?

Yes (unanimously)

We find the government and armed forces of the United States are guilty of the deliberate, systematic and large-scale bombardment of civilian targets, including civilian populations, dwellings, villages, dams, dikes, medical establishments, leper colonies, schools, churches, pagodas, historical and cultural monuments.

Have the governments of Australia, New Zealand and South Korea been accomplices of the United States in the aggression against Vietnam in violation of international law?

Yes (unanimously).

The question also arises as to whether or not the governments of Thailand and other countries have become accomplices to acts of aggression or other crimes against Vietnam and its populations. We have not been able to study this question during the present session. We intend to examine at the next session legal aspects of the problem and to seek proofs of any incriminating facts.

Endorsed ne variatur

The President of the Tribunal

Jean-Paul Sartre

Stockholm, 10 May 1967

In a memo to Johnson on May 19 1967, McNamarra warned:

"There may be a limit beyond which many Americans and much of the world will not permit the United States to go. The picture of the world's greatest superpower killing or seriously injuring 1,000 non-combatants a week, while trying to pound a tiny, backward nation into submission on an issue whose merits are hotly disputed, is not a pretty one. It could conceivably produce a costly distortion in the American national consciousness and in the world image of the United States."

In criminal cases the lawyer looks for evidence of a criminal state of mind. This view of the Secretary of State with responsibility for the bombing of Vietnam might be thought a very good starting point for finding criminal culpability; it is hardly a ringing assertion of legality in what was being done.

In November 1967. U.S. forces killed many enemy soldiers and destroyed large amounts of supplies. Westmoreland declared vast areas to be "free-fire zones," which meant that U.S. and ARVN artillery and tactical aircraft, as well as B-52 "carpet bombing" could target anyone or anything in the area. Ranch Hand the Agent Orange attack deprived the guerrillas of cover and food supplies. Controversy about the use of Agent Orange erupted in 1969 when reports appeared that the chemical caused serious damage to humans as well as to plants.

Late in 1967, with 485,600 U.S. troops in Vietnam and despite incredible losses, the Vietcong still controlled many areas. A diplomatic resolution of the conflict remained elusive. Several third countries, such as Poland and Great Britain, offered proposals intended to facilitate negotiations by mutual reduction of their military activities in South Vietnam, but both Washington and Hanoi firmly resisted even interim compromises with the other. The war was at a stalemate.

In United States v. Hart (October 1967) The Third Circuit rejected a conscientious objector’s argument: "[W]e do not subscribe to the contention that the Board was without power to direct him to report for assignment to civilian work. The Supreme Court denied review, with Justice Douglas dissenting stating that the Government was unable to cite a single Supreme Court opinion specifically holding that Congress possessed the constitutional power to conscript for the armed forces in the absence of a declaration of war.

In United States v. Holmes (November 1967) a conscientious objector convicted for failing to report claimed that compulsory civilian work in lieu military service during peacetime was a form of involuntary servitude. The Seventh Circuit found Compulsory civilian labor was an alternative to compulsory military service and was justified to preserve "discipline and morale in the armed forces." The Supreme Court declined review. Justice Douglas dissented explaining that the Court had "never decided whether there may be conscription in absence of a declaration of war. Our cases suggest (but do not decide) that there may not be."

In October 1967, 300 students at the University of Wisconsin prevented Dow Chemical Company, the maker of napalm, from holding a job fair on campus. Three police officers and 65 students were injured in the two-day event.

The next day October 21, documented by Norman Mailer in his novel Armies of the Night, a large demonstration took place at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. As many as 100,000 demonstrators attended the event, and at least 30,000 then marched to the Pentagon for another rally and an all night vigil interrupted by clashes with soldiers and police. In all, 647 arrests were made.

20 November – 1st December 1967 saw the Second Session of the Tribunal held at Roskilde Denmark with further expert reports, summaries from the region and questioning of US servicemen who had engaged in torture of Vietnamese or supervised the torturing of Vietnamese by South Vietnamese soldiers. It is difficult material to read although here is no reason to doubt the accuracy of what the soldier witnesses said including a detailed beheading of a live man, gross torture of prisoners, throwing prisoners from helicopters and a policy of taking no prisoners. More of this would emerge later in the aftermath of the My Lai massacre that did get to court but even at this early stage there was clear evidence of war crimes being committed by US servicemen and, if these witnesses were accurate, on a widespread basis.

Sartre wrote a paper on genocide that was adopted by the Tribunal. In 1967 the Genocide convention was nearly 20 years old and had another two decades to wait before it would be charged as a crime anywhere or be ratified by the USA. [The Eichmann trial in Jerusalem in 1961 did not include genocide charges]

Accordingly it is unsurprising that Sartre, unassisted by jurisprudence developed since, might have found genocide established on a basis broader than might now be acceptable. His analysis is also, inevitably, informed by his own strongly held political beliefs. The paper merits reading in full. He distinguished between genocide committed against unequal force in the seizing of colonies from genocide committed as anti-guerilla strategies that galvanise two peoples into total war. In Vietnam, he observed, the USA - unlike the departing French colonialist power – had little real economic interest in Vietnam but could use genocide as a strategy, if it chose, as a warning to the guerillas in the conflict and to those around the world who opposed US beliefs and values.

He concluded:

Total war implies a certain equilibrium of strength, a certain reciprocity. The colonial wars were waged without reciprocity, but colonial interests limited genocide. This present genocide, the latest development of the unequal progress of societies, is total war waged to the end by one side and with not one particle of reciprocity.

The American government is not guilty of having invented modern genocide, nor even of having chosen it from other possible answers to the guerrilla. It is not guilty - for example - of having preferred it on the grounds of strategy or economy. In effect, genocide presents itself as the only possible reaction to the insurrection of a whole people against its oppressors. The American government is guilty of having preferred a policy of war and aggression aimed at total genocide to a policy of peace, the only other alternative, because it would have implied a necessary reconsideration of the principal objectives imposed by the big imperialist companies by means of pressure groups. America is guilty of following through and intensifying the war, although each of its leaders daily understands even better, from the reports of the military chiefs, that the only way to win is to rid Vietnam of all the Vietnamese.

It is guilty of being deceitful, evasive, of lying, and lying to itself, embroiling itself every minute a little more, despite the lessons that this unique and unbearable experience has taught, on a path along which there can be no return. It is guilty, by its own admission, of knowingly conducting this war of ‘example’ to make genocide a challenge and a threat to all peoples. When a peasant dies in his rice field, cut down by a machine-gun, we are all hit. Therefore, the Vietnamese are fighting for all men and the American forces are fighting all of us. Not just in theory or in the abstract. And not only because genocide is a crime universally condemned by the rights of man. But because, little by little, this genocidal blackmail is spreading to all humanity, adding to the blackmail of atomic war. This crime is perpetrated under our eyes every day, making accomplices out of those who do not denounce it.

In the Conclusions of the Second session The Tribunal wants today to condemn:

The wholesale and indiscriminate use of napalm, which has been abundantly demonstrated before the Tribunal.

As for the use of gases, the Tribunal considers that the failure of the United States to ratify the Geneva Protocol of 17 June 1925, concerning the prohibition of the use in war of toxic or similar asphyxiating gases, is without effect, as a result of the voting by the General Assembly of the United Nations (a vote joined in by the United States) on the resolution of 5 December 1966, inviting all states to conform to the principles and objectives of the said Protocol, and condemning all acts contrary to these objectives.

The scientific reports of the most qualified experts, which have been submitted to the Tribunal, demonstrate that the gases used in Vietnam, in particular CS, CN and DM, are used under conditions which make them always toxic and often deadly, especially when they are blown into the hideouts, shelters and underground tunnels where a large part of the Vietnamese population is forced to live. It is impossible to classify them as simple incapacitating gases; they must be classified as combat gases.

The Tribunal has studied the current practice of the American army consisting of spraying defoliating or herbicidal products over entire regions in Vietnam. It has noted that the American manual on the law of war already cited forbids destroying, in particular by chemical agents - even those theoretically non-harmful to man - any crops that are not intended to be used exclusively for the food of the armed forces.

It has found that the reports of the investigative commissions confirmed the information, from both Vietnamese and American sources, according to which considerable areas of cultivated land are sprayed by these defoliating and herbicidal products. At least 700,000 hectares [about 1,750,000 acres] of ground were affected in 1966.

First, in the course of raiding operations which take place both systematically and permanently, thousands of inhabitants are massacred. According to serious information from American sources, 250,000 children have been killed since the beginning of this war, and 750,000 wounded and mutilated for life. Senator [Edward] Kennedy’s report, 31 October 1967, points out that 150,000 wounded can be found every month. Villages are entirely levelled, fields are devastated, livestock destroyed; in particular, the testimony of the American journalist Jonathan Schell describes in a startling way the extermination by the American forces of the population of the Vietnamese village of Ben Suc and its complete destruction. Precise testimony and documents that have been put before the Tribunal have reported the existence of free-fire zones, where everything that moves is considered hostile which amounts to saying that the entire population is taken as a target.

Verdict of the Second Session [that was also significantly concerned neighbouring countries] included:

Have prisoners of war captured by the armed forces of the United States been subjected to treatment prohibited by the laws of war?

Yes (unanimously).

Have the armed forces of the United States subjected the civilian population to inhuman treatment prohibited by international law?

Yes (unanimously).

Is the United States Government guilty of genocide against the people of Vietnam?

Yes (unanimously).

Is that the end of what I need say? Does this verdict show that:

There was enough evidence to have the USA inquired into for war crimes, as many had effectively argued to the deaf ears of its own Supreme Court; and as there was no formal inquiry this informal Inquiry is of great value and can count as the last word on the subject?

To the questions I asked at the start I have these comments:

First, there was a serious shortcoming of the Russell Tribunal. Surprisingly, given the publicity attached to the Nuremberg Process being ‘Victor’s Justice’, the Tribunal declined to assess the conduct of the other side:

Staughton Lynd, chairman of the 1965 “March on Washington”, declined Russell’s invitation to participate in the tribunal because Russell planned to investigate only non-North Vietnamese and National Liberation Front conduct and would Hanoi from any criticism for their behavior. David Horowitz, a member of the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation, confirmed in his memoirs overhearing Jean-Paul Sartre insist that the North Vietnamese and National Liberation Front were, by definition, incapable of committing war crimes. "I refuse to place," said Sartre, "in the same category the actions of an organisation of poor peasants... and those of an immense army backed by a highly organized country." Sartre continued to ignore the genocide committed by the Vietcong and North Vietnamese Army after such famous massacres as the Dak Son Massacre and Hue Massacre.

Second, the Tribunal’s conclusions were largely confirmed by evidence coming to light after it pronounced its verdict – the My Lai massacre, the Pentagon Papers, McNamarra’s expressed views.

Third, its conclusions adverse to the USA would probably have been the same even if it had surveyed the actions of all sides to the conflict.

Fourth, it is not at all clear that this Tribunal did make a difference because when a powerful body declines to engage – as the US did with the world in any formal setting (none existed) and as the Supreme Court did with the US citizens – there is no way to make it do otherwise. With the passage of time people forget. Only with total, public, visible defeat – such as exemplified by the Nazis at Nuremberg – will public memory of what has been done remain strong.

© Professor Sir Geoffrey Nice 2013

Notes

[1]The Convention defines chemical weapons much more generally. The term chemical weapon is applied to any toxic chemical or its precursor that can cause death, injury, temporary incapacitation or sensory irritation through its chemical action. Munitions or other delivery devices designed to deliver chemical weapons, whether filled or unfilled, are also considered weapons themselves. http://www.opcw.org/about-chemical-weapons/what-is-a-chemical-weapon

[1]Globalization and Autonomy Online Compendium, a collective publication by the team of leading Canadian and international scholars who are part of the SSHRCC Major Collaborative Research Initiative on Globalization and Autonomy.

[1]Sean Thomas, Daily Telegraph http://blogs.telegraph.co.uk/news/seanthomas/100235050/spare-us-the-hypocrisy-over-chemical-weapons-america-what-about-agent-orange/

[1]United Nations General Assembly Resolution 1514 of 14 December 1960, "Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples"

[1]David L Anderson - From The Oxford Companion to American Military History. Ed. John Whiteclay Chambers II. New York: Oxford UP, 1999. Copyright © 1999 by Oxford UP.

[1]"On Civil Disobedience", April 15th, 1961

[1]David L Anderson - From The Oxford Companion to American Military History. Ed. John Whiteclay Chambers II. New York: Oxford UP, 1999. Copyright © 1999 by Oxford UP

[1]David L Anderson - From The Oxford Companion to American Military History. Ed. John Whiteclay Chambers II. New York: Oxford UP, 1999. Copyright © 1999 by Oxford UP

[1]The author is indebted to Rodric B. Schoen for his article ‘A Strange Silence: Vietnam and the Supreme Court HeinOnline’ - 33 Washburn L.J. 275 1993-1994 – that analyses cases concerning the Vietnam War that are referred to here and below

[1]Treaty of London of August 8, 1945, 59 Stat. 1544, Article 6(a) declares that 'waging of a war of aggression' is a 'crime against peace' imposing 'individual responsibility.' Article 8 provides: 'The fact that the Defendant acted pursuant to order of his Government or of a superior shall not free him from responsibility, but may be considered in mitigation of punishment if the Tribunal determines that justice so requires.'

[1]In its 1993 Statute, after these events, the ICTY identified existing law that was also in place at the time of the Vietnam War

[1]Members: Wolfgang Abendroth,Tariq Ali, Gunther Anders, Mehmet Ali Aybar , A.J. Ayer, James Baldwin, Lelio Basso, Julio Cortázar, Lázaro Cárdenas, Stokely Carmichael,Lawrence Daly,Simone de Beauvoir,Vladimir, Dedijer,David Dellingermm Isaac Deutscher, Gisele Halimi, Djamila Bouhired, Amado V. Hernandez, Melba Hernandez, Mahmud Ali Kasuri, Sara Lidmanr, Carl Oglesby, Bertrand Russell, Shoichi Sakata, Jean-Paul Sartre, Laurent Schwartz, Peter Weiss

[1]David L Anderson - From The Oxford Companion to American Military History. Ed. John Whiteclay Chambers II. New York: Oxford UP, 1999. Copyright © 1999 by Oxford UP

[1]Obituary in Daily Telegraph

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/politics-obituaries/5760914/Robert-McNamara.html

[1]David L Anderson - From The Oxford Companion to American Military History. Ed. John Whiteclay Chambers II. New York: Oxford UP, 1999. Copyright © 1999 by Oxford UP

[1]Lynd, Staughton (December 1967). The War Crimes Tribunal: A Dissent. Liberation.

[1]David Horowitz, Radical Son: A Generational Odyssey, page 149

Login

Login