What will happen when Artificial Intelligence and the Internet meet the Professions?

Share

- Details

- Text

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

Two futures are outlined for the professions. Both rest on technology. One is reassuringly familiar. It is a more efficient version of what we have today. The second is transformational - a gradual replacement of professionals by ‘increasingly capable systems’. In the long run, in an Internet society, it is claimed, we will neither need nor want doctors, teachers, accountants, architects, the clergy, consultants, lawyers, and many others, to work as they did in the 20th century.

Download Text

30 March 2017

What will happen when

Artificial Intelligence and the

Internet meet the Professions?

Richard Susskind and Daniel Susskind

Here is what I would like to do over the next 45 minutes or so, and then have an opportunity for question and answer. Daniel will be talking about the two futures that we see for the professions and will be taking you to the leading edge, to the vanguard, to give you a flavour of what is already happening as a result of the application of technology in the professions. I will come back and I will talk about some broad trends that we see across the professions and suggest to you there is an evolutionary path along which the professions are evolving, and then I also want to speak about technology, which will take me into artificial intelligence. That will raise the question “Will we have any jobs in the future?” Daniel is going to answer that question and then say a little about different ways in which we might make expertise available in society. So, without further ado, I hand you over to my co-author, Daniel, to take it from here.

Daniel

Thank you very much. It is also a great pleasure to be here this evening. So, I want to talk first about these two futures that we see for the professions. This is the book, and I suppose the most common question that we get asked is how we came to write the book together and, you know, what can I say about a co-author who, in many ways, has become like a father to me?!

As you would have heard in the introduction, my Dad has spent the past 25, 30 years trying to understand how technology affects the legal profession, and what he has found, particularly in the last few years, is that, at the end of talking to audiences predominantly of lawyers, a stray teacher, a stray doctor, a stray architect would approach and say, “Look, what you are talking about, that is all very interesting, but actually it applies equally well in our profession too.” We first spoke about this back in 2010, and I was working in Downing Street at the time, working on lots of different policy areas, on tax policy, on health policy, on education policy, but with a good overview of lots of different professions, and it was clear then that significant change was in the air and that these professions appeared to face a common set of challenges. So, we had this idea of joining forces to investigate the professions more generally, and that is exactly what we did, and the result was the book, ‘The Future of the Professions’.

In the book, we look at eight professions, not just lawyers, but also doctors, teachers, accountants, architects, engineers, consultants, journalists, and we even look at the clergy, but the thinking in the book is not meant to just apply to those professions though. It is meant to apply to all professions. In part, it draws on a set of around 100 interviews we did, both with traditional professionals but also, again, those people and institutions at the vanguard who are trying to solve these problems differently, and it draws on hundreds of sources too. There is a lot of traditional print publications but an awful lot, if you have a look at the footnotes, of online material too. The picture that we get is of radical change, and our work is trying to make sense of this change. Very broadly, what we see are two futures for the professions.

The first future, I think, is a reassuringly familiar one. It is simply a more efficient version of what we have today, and here, professionals of all different stripes use technology but essentially just to streamline and optimise the traditional ways in which they have worked, and this is the professions, in some cases, since the middle of the 17th and 18th Century, and as you look across the professions, there are lots of examples of this: It is doctors talking to patients via Skype; it is architects using computer assisted design software to design bigger, more complicated buildings; it is tax accountants using tax computation software to do harder, more intractable calculations. So, that is the first future.

But there is then also a second future, and this is a very different proposition, and here, technology does not just streamline and optimise the traditional ways in which these professions have worked but actively displaces the work of traditional professionals. What we call in the book, and it is an idea we will come back to again and again, increasingly capable systems and machines, either operating alone or, and this is quite important, just designed and operated by people that look quite unlike traditional professionals, they gradually take on more and more of the tasks and activities that we associate with traditional professionals.

The argument we develop in the book is that, for now, and in the medium term, we will see these two futures developing in parallel, that we are going to see examples of both, but we think that, in the long run, that second future will dominate, that through technology, we will find new and better ways of solving the sorts of problems that traditionally only a very particular type of professional has solved, and we argue this will lead to the dismantling of parts of those traditional professions. So, that is where the thinking and the evidence led us, but it also led us to ask a more fundamental question, and it was this, and we open the book with it, why do we have these professions at all? Why do we have them? The answer to that is that the professions, although, from a distance, they look quite different, actually, in analogous ways, they are all a solution to the same problem, and the problem is this: it is that nobody has sufficient specialist knowledge to cope with all the daily challenges they face in life. Nobody can know everything. Human beings have limited understanding of the world around them, and so we turn to professionals of all different types because they have the expertise that we need to make progress in life.

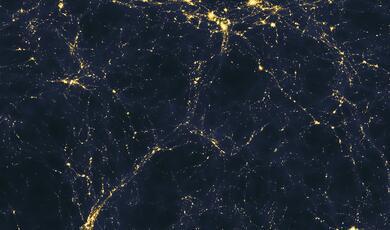

In what we call a print-based industrial society, the professions are the way that we solve these daily challenges. They have the knowledge, the wisdom, the know-how, the experience, the expertise, and our term for all of these things is they have the practical expertise. They have got this practical ability to solve these difficult problems that those they help do not. They operate under a grand bargain, and it is an arrangement that differs across jurisdictions and differs across professions, but it is an arrangement that essentially entitles the professions, often to the exclusion of others, to provide certain types of services, and they are entrusted to act as gatekeepers, each profession responsible for its own unique body of knowledge. So, doctors look after medical knowledge, lawyers look after legal knowledge, accountants look after accounting knowledge, and so on. So, this is our analysis of the professions in this print-based industrial society, but we are no longer in a print-based industrial society. We are in what we call a technology-based internet society, and those traditional professions are creaking.

They are unaffordable, in that most people, and most institutions, simply do not have access to the expertise of first-rate professionals or, in many cases, any professionals.

They are antiquated. By and large, the professions, when you look at it, rely upon pretty old-fashioned ways of producing and sharing knowledge and information, despite the existence, in many cases, of feasible alternatives.

They are opaque. Sometimes this is because the work the professions do is genuinely too complicated for ordinary people to understand, but other times – and take a walk through a courtroom just down the road and have a look at the oak-panelling and the wigs, you get the sense there is some intentional obfuscation at work there too.

Finally, the professions underperform – and we mean something very particular by this. Given the way we organise expertise in society, in the heads of professionals or buried away in their filing cabinets and systems, the expertise of the very, very best, it is a very scarce resource. Only a privileged and a lucky few have access to it.

So, we ask this question: as we move from this print-based society to an internet society, might there be new ways of organising professional work? Might there be new ways to solve the sorts of problems that traditionally only the professions have solved? Do we necessarily need those traditional gatekeepers anymore?

To answer that question, we went to the vanguard, to a group of people and institutions, again, who are trying to do things differently. In the book, there are hundreds of case studies. Just now, I want to run through some of them just to give you a flavour of the sort of thing that we are talking about.

So, in education, more people signed up for Harvard’s online courses in a single year than attended the actual university in its entire existence up until that point.

Khan Academy is an online collection of practice problems and instructional videos. I often direct my students towards it. It is a very high quality resource. It has 10 million unique users a month. That is more unique users than the entire school population of England.

In medicine, WebMD is an online collection of health websites, guidance on symptoms and treatments – it has 190 million unique users a month. That is more unique users than there are visits to all the traditional doctors working in the United States. The US Food & Drug Administration has said that, by 2018, there will be at least 1.5 billion people with one or more medical apps on their smartphone.

DeepMind – it is a system that was developed in fact by a team of researchers here in London at UCL, and it was designed to play the game Go, an incredibly complicated game, so complicated that most people in artificial intelligence thought, until very recently, we were about a decade away from ever building a system that could beat a human expert at Go. Now, in March of 2016, this system, DeepMind, sat down with Lee Sedol, who at the time was the world Go champion, the best living Go player, and it beat Lee Sedol four games to one, it was livestreamed on YouTube and it was really remarkable. What is interesting though is that Google bought DeepMind shortly after, and Google of course did not buy DeepMind for the fortune it did because it wants to be good at board-games – that is not what they are doing. One of the first things they did was they teamed up with Moorfields Eye Hospital, again just down the road, and they are using this system or a similar system to try and diagnose various types of eye problems.

In the world of journalism, Huffington Post, on its sixth birthday, had more unique monthly visitors than the New York Times, which then was about 164 years old. Associated Press, a few years ago, started to use algorithms to computerise the production of their earnings reports. So, using these algorithms, they now produce about 15 times as many earnings reports as when they relied upon traditional financial journalists alone.

In the legal world, on eBay, every single year, 60 million disputes arise and they are resolved online without any traditional lawyers, using what is called an e-mediation platform. Just bear in mind 60 million disputes… That is 40 times the number of civil claims that are filed in the entire English and Welsh justice system and they are resolved on this one website without any traditional lawyers, 60 million of them, 52 million of them without any human mediation at all. Again, in the US, it is said the best known legal brand is not a traditional law firm anymore, it is LegalZoom.com, an online document drafting and legal advice platform.

Just a few weeks ago, JP Morgan, again in law, they announced their use of some software called COIN, Contract Intelligence, and it scans commercial loan agreements. It reads and interprets them. It does in a couple of seconds what would have taken human lawyers, it is estimated, up to 360,000 hours of work.

In the world of tax, a few years ago, 48 million Americans, in 2014, used online tax preparation software rather than a traditional tax accountant to help them. IBM Watson – Watson is a supercomputer owned by IBM, and we will talk about it a little more later – in 2011, it went on a US quiz show, Jeopardy, and beat the two best living human Jeopardy champions. Just have that in the back of your mind. The point about it is though, again, IBM have not developed this system to play TV shows. They have teamed up, again in the world of tax, with H&R Block, which is an automated tax preparation system in the US, to engage with people as they complete their tax returns. Also, in Japan, Fukoku Mutual Life Insurance Company have started to use the system to computerise the decisions made around premium pay-outs, which is very interesting.

In the world of audit, the traditional way in which we do an audit, we want to look into the financial health of a company but there are too many financial transactions to review them all, we simply cannot do it. What we have developed, over hundreds of years, is a method by which we take a sample, so a small number of those financial transactions, we have various methods for trying to ensure that the sample we take is, in some sense, a good picture of the rest of the transactions – there is too many of them so we cannot view them – and then we extrapolate. We generalise, from this small sample, and if this small sample looks okay, then we say that the broader population of data must also be okay and so the financial health of this company is fine. That is the general approach – sample and extrapolate. That is no longer the approach though that some of the big accounting companies are taking. So, this system, HALO, at PwC, the intention is to use all financial transactions, not just take a small sample of them, but run algorithms through the entire population of data that’s available.

In the world of architecture, Gramazio Kohler, a Dutch firm, used a swarm of autonomous flying robots to build this structure out of 1,500 bricks. Again, it is interesting, a Dutch firm, WeBuildHomes.nl, so in fact a website, and architects go onto this website and out of what are essentially digital Lego blocks, they build buildings, and then people who are looking for a home can go onto this site, sift through the buildings, choose one they like and it gets delivered to them – a very different way of thinking about architecture and construction.

A few months ago, a new concert hall opened in Hamburg. It has got 10,000 acoustic panels in it, and it was designed entirely algorithmically. So, what they did was they specified a set of design criteria – we want it to have these acoustic properties, we want it to use these materials, we want it to seat this many people, or even very specific things such as if there was a panel within reach of somebody in the audience, it had to have a particular texture, and it took these design criteria and generated a set of possible buildings, and the architects could then choose, the sort of thing that might traditionally have required a designer or an architect to do.

In the world of consulting, Accenture, a consulting firm, does not just employ consultants anymore. It has 750 hospital nurses on its staff. McKinsey, a consulting firm, does not just offer traditional face-to-face, one-to-one, consultative advisory consulting services where you sit down with a human being. Now, they have 12 pre-packaged, off-the-shelf data analytics bundles that they install at their clients – a very different way of offering the expertise of a consultant.

As I said, we looked at divinity in the book, and this is I think my favourite example, and it is very divinity. In 2011, the Catholic Church issued the first ever digital imprimatur. An imprimatur is the official licence granted by the Catholic Church to religious texts. It granted it to this app called Confession, which helps you prepare for confession. So, it has got various tools for tracking sin and it has got dropdown panels of options for contrition. I encourage you have a Google actually because it was incredibly controversial at the time. The issuing of imprimaturs in the Catholic Church is decentralised. A church somewhere in North America issued an imprimatur for this app. It caused such a stir that the Vatican itself had to scamper and release an announcement saying that, look, while you are allowed to use this app to prepare for confession, please remember that it is no substitute for the real thing.

That is a flavour of the sort of thing that we’re trying to make sense of. I will hand over to my Dad to take it from here…

Richard

So, we tried to identify trends across the professions in light of this research. We will not detain you with all of these this evening, but we identified eight broad patterns and 30 trends, and one of them which actually dominates the professional services world is what we call the “more for less” challenge. Whether you be a lawyer or a doctor, an accountant or architect, the pressures are very clear today that there is an expectation you deliver more legal service or more medical service at lower cost, so this cost pressure, absolutely prevalent across the profession. New competition, often from start-ups and technology businesses, are providing new solutions to old problems. A move away from what we call the bespoke service, the handcrafted approach, the finely honed, tailored offering of the traditional craftsperson towards a more – and I will say more about this in a second – a more commoditised service. A move also towards decomposition, the breaking down of complex work of professionals into sub-parts, sub-components, and finding the most efficient way of doing some of these components. And then the routinisation, this drive towards identifying – and this makes good sense – areas of professional work that, frankly, can be done again and again in a broadly similar way. We do not need the craftsmen on all occasions, to start with a blank canvas.

We have another way of putting this, and it is in terms of the evolution of professional service. If you start with this notion, in the beginning, professionals are craftspeople, and then you see, across the professions, the introduction of standardisation, standard methods in terms of process and substance of doing the same work again and again, and then you see the systematisation, the application of technology, and this is still within the professions, within firms, within schools, within hospitals.

Then there is the phenomenon that we call the externalisation. As the internet has become widely available, it has been possible to make professional content, guidance, documents, materials, online, and that is done broadly in three ways - you can do it online on a chargeable basis – so we have already seen examples of professional firms that charge for their online products; you can do it on a non-chargeable basis – you will find governments and educational establishments and charities making content and advice and documents available online; or you can also do it in the spirit of Wikipedia, of open-source software – it is a shared resource that neither the state nor the market owns and controls. We call this movement from left to right, from craft towards the different forms of externalisation, we call that the commoditisation of professional service. You might call it the industrialisation or you might call it the digitisation. Basically, we are seeing in the professions what we have seen in so many other sectors: identification of aspects of work that can be done, that is routine and that can be done either in a standardised or systematised or in an online way.

So, technology underpins all of this. I want to take you back to 1996, and it is interesting, just reflecting, it was only four years after that that I had the privilege of becoming a Gresham Professor of Law, and I was speaking a lot at the time about a book I had written then called “The Future of Law”. In “The Future of Law” I made what I am sure you will agree is a bold claim. I said that, in the future, the dominant way that lawyers and clients would come to communicate would be by email. So, it does not sound like an exceptional pronouncement. At the time, I joke not, the Law Society of England & Wales said I should not be allowed to speak in public and that I was bringing the legal profession into disrepute by suggesting that email would be widely used. I say that today because we will be talking about a whole bundle of technologies over the next few minutes and your inclination might be, “Well, I am not really sure they will work in the professions.” They are all far more likely than email was for lawyers in 1996.

We think the best way of understanding what is happening in the world of technology – and there are many ways of explaining it, but our way of explaining the world of technology is under four headings, and I am going to say quite a bit about two of them. The four headings are that the underpinning technology is growing at an exponential and explosive pace. Our systems, as Daniel said, are becoming increasingly capable, able to do more and more, often tasks that we thought only human beings could take on; and I will say no more about these just now, but our systems are becoming increasingly pervasive, not just handheld machines and tablets but also the intranet of things, microchips embedded in everyday objects, even embedded in human beings, and also, as we know, as human beings, we are increasingly connected, through social media for example, in different ways. But let us say a little about exponential growth.

Another law of the land, Moore’s Law, and there are many ways of describing this, but Gordon Moore, a man who 52 years ago said something that does not sound particularly exceptional: he said every couple of years, the processing power of computers would double. Very approximately, that is what he said. Now, that does not sound such a big deal, but I want you to think about the story of the tramp and the princess. The tramp saved the princess’ life. The king says to the tramp, “By way of reward, I will give you anything in the kingdom.” The tramp responds, and it turns out this is a mathematically astute tramp, the tramp says, “I want something quite simple – I would like a chessboard, and I would like you to put a grain of rice in the first square, double it in the second square to two, double it again to four, and just keep on doubling, right round the 64 squares, and that will be sufficient as my reward.” The king thinks he has gotten away lightly, but the king, clearly, is not mathematically astute because it turns out this would require more rice than exists on Planet Earth. That is what happens when you keep doubling in any phenomenon, and what we are seeing is a doubling in processing power, so that, by 2020, there is fairly widespread agreement that the machines will be able to process, an average desktop machine, at the speed of about 10 to the 16th or 10 to the 17th calculations per second. That is about the same processing power as the human brain – not to say it is artificially intelligent, but just to give you a sense of the processing power. What is remarkable is that, if Moore’s Law continues - and there is some discussion here but most material scientists and computer scientists believe, in one way or another, there will be a doubling of processing power every couple of years till 2050 – by 2050, this means the average desktop machine will have more processing power than all of humanity put together.

This sounds terribly improbable, but we live in improbable times. We live in a time of greater and more rapid technological progress than humanity has ever witnessed, and we asked the professions whether or not we can reasonably believe this will not affect the way we work when you have this sort of processing power available to our children or our grandchildren. Am I exaggerating, you might ask…

Well, look at this quotation. Clearly, the machine does not like this quotation, but this is by a Nobel Prize winner, Michael Spence, who noted, in 2001, and this comes to the same thing as a doubling in processing power, he noticed, essentially, a halving in the cost of processing power every couple of years, roughly a 10 billion times reduction in the cost of processing power in the first 50 years of the computer age. Remember, that was 2001, so 2003, it would be 20 billion, 2005, 40 billion, and so forth.

For those of you who are cynical, just think about this – we found this remarkable, the little card you fit in your camera: 2005, a good card, 128mb; 2014, less than 10 years later, 128gb – more than a thousand-fold increase in less than 10 years. That is more than a doubling each year. Whether it be bandwidth, random access memory, hard disk capacity, external storage, processing power, the amount of data flying about, we are seeing this exponential explosive effect.

This is enabling our systems to become increasingly capable, and we look at four different dimensions to this, and I will say a little about each. The whole idea of Big Data, predictive analytics, machine learning, you will have heard all of these phrases, but the underpinning idea here is quite simple, that if you have got lots of data – and we create so much data, even in a simple web search, by any of us, there is lots of data created as a by-product - but this data, the data exhaust, as it were, that comes flying out behind us, if we analysed this using appropriate technologies, it itself can yield insights, patterns, correlations.

So, consider Lex Machina, a system now owned by a business called LexisNexis but originally developed in Stanford, and this system, it is claimed, can predict the outcome of patent disputes more accurately than many lawyers. It knows nothing about patent law. It is making a statistical prediction about the behaviour of the courts. It has got over 100,000 records of individual cases - who the judge was, what courtroom it was in, the law firm involved, the lawyer involved, the party involved, the size of the claim, the nature of the claim. It turns out if you have enough information about the past features of cases, you can make a more accurate prediction than lawyers doing their legal reasoning and legal problem-solving. Now, many people say, well, hang on a second, this system knows nothing about the law, and that is true. But just ask yourselves for a second if any of you, or any businesses about to be involved in litigation, what is the question we all ask? What are the chances of winning? Everyone asks that question. You may remember, the great Abraham Maslow once said, “If you are a hammer, everything looks like a nail.” Well, for a lawyer, everything looks like a legal problem. So, when people hear the question from a Chief Executive “What are our chances of winning?” the lawyer will think that’s a legal question. In fact, it is a question about statistics, about likelihood.

Machines are starting to outperform human beings, and we are seeing it in medicine as well. So, data science, in not many years, many people are predicting will trump medical science, will be able to make more accurate predictions on the basis of past data.

And then we have, as Daniel said, examples of what are called QA systems, question and answer systems, machines that can actually answer questions. IBM’s Watson won on this TV quiz show, beat the two best ever human Jeopardy champions – that is the name of the quiz game, about the same degree of difficulty as Mastermind. That was in 2011.

So, you have got this idea that machines, from huge amounts of data, can identify patterns, correlations, even come up with insights - we heard about the AlphaGo system, DeepMind – come up with new moves that no human being had ever thought of, and then systems that can actually have stores of knowledge represented within them as well as elements of Big Data and actually are outperforming in answering questions, more accurately and more rapidly than the best human beings.

This technology is amazing, affective computing, machines that can recognise, detect and express human emotions, a machine that can look at any of your faces and tell whether or not you are happy, surprised, angry or disgusted. A machine, more accurately than any human being, can now look at a human smile and tell whether or not it is fake or genuine.

Then of course we have driverless cars. Not many years ago, leading labour economists were saying this was unimaginable, this would never happen, and now we are seeing most advanced economies expecting, by the mid-‘20s, this will dominate the driving of trucks and cars on the road.

We are moving at a remarkable rate. What I find most interesting when you consider these four factors together is there is no finishing line. No one in Silicon Valley is dusting their hands off and saying “That is enough, job done, let us just call it a day, come on, enough is enough!” No one is saying “Enough is enough”. “Enough” is not in their language. The rate of change itself is accelerating.

This takes us to the world of artificial intelligence, which is a nostalgic journey for me because, in the ‘80s, I wrote my doctorate in Oxford in IA in Law. I was involved in the first wave of these systems, and from ’86 to ’88, developed the world’s first commercial AI system in law. It looked like this. I know it is embarrassing now, but that is what it looked like, and it was a system that was loaded on – this was when floppy disks genuinely were floppy, ladies and gentlemen! It solved this problem: Section 2 of this Act shall not apply to an action to which this section applies. Someone, somewhere, at some stage, thought that was okay as a piece of guidance to humanity! A piece of legislation, very complicated, I will not trouble you with its details, but really to do with when an action in law can no longer be raised because too much time has passed – it is called the law of limitation. I sat down with a man called Philip Capper, who was the leading expert in this area, and he had written the leading book in the area, and we developed a big decision tree of his expertise in this area. It was very basic questions the user was asked, but essentially, you were being guided through over two million possible paths in this very complex area of law, and the system, in the end, he would say still, to this day, was better than him. It could more accurately and more rapidly tell you the date after which your action was stale, more accurately than the leading human expert, reduce research time from hours to minutes. We were not alone in the ‘80s – people in law were working alongside people in medicine and tax and audit and consulting. Everyone engaged in a certain form of AI, which was really to get a machine to do something clever, you put together a clever representation of a human being’s knowledge and you put it into a computer system and you make it available. So, the power of the system was to make the clever model available. We have moved on from that, and that is the second wave. These systems were costly to develop, and not huge incentives at that time. There was not the “more for less” challenge in the legal world. Clients were clamouring for lower fees. Competitors were not undercutting firms. Why would they want to reduce their time from hours to minutes when they were charging by the hour? What actually probably killed AI in the professions was the web. It came along and, immediately, we had a more intuitive, easier, less expensive way to make legal guidance, legal content available at no cost.

Then something remarkable happened in ’97: Garry Kasparov, the world chess champion, was beaten by Deep Blue. In the ‘80s, we thought that would never happen because, remember, how we thought you got a computer system to perform at a high level was to essentially draw a big decision tree of an expert or an expert’s reasoning and put it in a computer system, but here is the problem: leading chess players, leading doctors, and others, said, “Well, I do not know where my ideas come from.” Doctors will say, “It is just experience, it is intuition, when I look at a disorder or I hear some symptoms”, and a chess player will say “I cannot articulate the rules I follow.” So, there seemed to be some realm of tacit knowledge, ineffable knowledge that could not be articulated. A happy conclusion in the ‘80s for AI. So, the computer systems, they do the basic rule processing, where we can reduce expertise to a set of rules and we can put that into a system, but the real magic, the insight, the expertise, the genius must come from human beings… no system could provide that.

What we had not banked on was this exponential increase in processing power. By the time Kasparov was beaten by Deep Blue, this was a system that could process more than 330 million moves in one second. A good chess player, with a following wind, can only juggle about 100 moves in his or her head at one time. Kasparov was not beaten by an artificially-intelligent system that had genius or insight like a human being; he was beaten by brute processing power, lots of data, and clever algorithms. That, ladies and gentlemen, is what will take over, in combination, much of the work of professions.

It is key to notice here that there are lots of ways of being smart that are not smart like us. Patrick Winston, one of the fathers of academic AI, wrote to us – it is a great quotation. We tend to think, as human beings, and we call this the “AI fallacy” – we make the mistaken assumption that the only way we can develop systems that perform tasks at the level of experts or higher is to replicate the thinking process of human specialists. So, many doctors and lawyers and accountants say, “Well, you do not really understand – a machine cannot think and that is how we sort out a problem.” That assumes that the way you make machines perform at a higher level now is simply by replicating the way human beings perform, and that’s a fallacy. So, the professionals say to me, “What about judgement? How can a computer system ever exercise judgement? That is why my clients come to me.” We say, in response, actually, there are two better questions.

Firstly, to what problem is judgement a solution? Why do people come to human experts in the first place? Daniel has explained, they are after this practical expertise. They need this expertise, usually, because there are conditions of uncertainty. In law, for example, facts are uncertain, the law is uncertain. In your experience, in your judgement, what is the situation? So, the question is not “Can a computer exercise judgement?” because judgement is the way that human beings answer problems of uncertainty; the better question is “Can a computer handle uncertainty?” and all the experience in the world of Big Data and predictive analytics and machine learning is, actually, machines are better than human beings at handling uncertainty insofar as they can contain and process massive amounts of past experience. We saw that with Lex Machina. Can machines think? It is a great question. We love it. We both trained in Philosophy. It is a red herring though. Machines are outperforming human beings without being conscious or having cognitive states.

We love this story. When Watson beat the two human champions on Jeopardy, the next day, a great philosopher called John Searle, and the Wall Street Journal wrote an article that was headed this, “Watson does not know it won in Jeopardy”. Is that not brilliant? Watson did not want to phone up its mum to say how it felt, it did not want to go down to the pub to celebrate – Watson did not want to do anything. Watson is a non-thinking machine. What we are seeing is the emergence of increasingly capable non-thinking machines that are outperforming us, and that is the second wave of AI and it has profound implications for jobs in the future.

Daniel

One of the difficulties we have when we think about the future of work and we think about the future of jobs is that, actually, the term “jobs” is quite misleading, and it is misleading because it encourages us to go back to that idea of decomposition before – it encourages us to think of the work that people do as monolithic, indivisible lumps of stuff, when, actually, when you look under the bonnet of any job and you look at what anyone does, they perform lots of different tasks, lots of different activities. So, why does this matter for thinking about the future of work?

When we published the book, the Economist wrote a review of it, and I should say, it was a good review otherwise I would not have mentioned it, but alongside it was this great cartoon of Professor Dr Robot QC. Now, there is a sense, when we are of that jobs mind-set, that the way technology affects work is that one day somebody will turn up at work and find Professor Dr Robot QC sitting at their desk – their job will have been taken by a robot. That just simply is not how technology affects the work that people do. What it does is it changes the types of tasks and activities that people do, sometimes giving them new tasks, sometimes automating away tasks, and so we think, in the medium run, the challenge here is not one of unemployment, instead it is one of redeployment. It is a story about how the tasks and activities that have to be done to solve the sorts of problems that traditionally were only done by a very particular type of professional, that those tasks and activities are going to change, and in the book, we look at 12 of these. I cannot go into them in depth now, but just let me make two observations. The first is that when many professionals look at this list, these sorts of things are not – they do not see it as being part of their job. This is not what is in a traditional professional’s job description. The second point is that, actually, many of these tasks and activities require skills and capabilities quite unlike the sorts of things that we train many traditional professionals to do. So, I think both those things beg the question whether or not traditional professionals will be best placed to perform many of these tasks and activities in the future.

So, in thinking about the future of professional work, people really have two strategies, if they want to be in this world. One is you either try and compete with the machines, so you try and do the sorts of things that, at the moment, people rather than machines are best-placed to do, and there still are large areas of human activity where that is the case – many creative tasks, many things that require interpersonal skills, and so on. Or the second strategy is that you instead become the sort of person that is capable of building and designing and operating these systems and machines. Now, of the two strategies, the latter I think is the more appetising one. If you are asking what is going to happen in the future as these systems and machines become more capable, well, one thing is that they are going to be able to perform more types of tasks and activities, so that set of things in which people can effectively compete with machines, it is only going to get narrower and narrower and narrower over time.

Let me say something about expertise. When we began the book, our main preoccupation was with the work of traditional professionals. We wanted to know what was happening to the work of doctors and lawyers and teachers and accountants and so on. But, actually, as our thinking progressed, we realised there was a far more fundamental question that we had to answer, and it was this, which is: how is it that we produce and share this practical expertise in society, this ability to solve these difficult problems? Now, it is very clear the traditional answer to this has been through the professions. When we have certain types of problems, when we have these challenges, we go to professionals and they have the practical expertise that we do not. What is happening I think, as we move from a print-based society to an internet society, is that we are seeing the emergence of new models, new ways of producing and sharing practical expertise, new ways of getting access to that ability to solve these difficult problems. So, let me just give you a flavour of each of these.

The first is the networked experts model. This is perhaps closest to the traditional professional model, still experts, but rather than congregating in a physical bricks and mortar institution, instead they use online platforms to work in a far more flexible, far more ad hoc way. The Economist called this “workers on tap”.

Then there is the para-professional model. Think of this as a professional firm with lots of inexpert people at the bottom and fewer expert people at the top. The traditional conception that many people have of these systems and machines is that they eat away at the stuff at the bottom of that pyramid, the inexpert stuff at the bottom, but actually, there is a very different model. So, this is the logo for that system I described right at the start, the AlphaGo system, which is the DeepMind system which has been developed for Moorfields. It is entirely conceivable that, in the future, when you go to a hospital, you will be greeted by a nurse or a nurse-practitioner, rather than a doctor, who, with one of these very sophisticated diagnostic systems, is able to offer the sort of support that might have required a more expert person in the past but they are also able to offer, for example, the sort of empathetic support that, if we are frank, actually, a lot of experts traditionally lack, and this challenge, I think, that, actually, one of the ways technology might change work is by allowing less expert people to do work that might have had to be done by more expert people in the past I think is an interesting model that we’re seeing developing in various settings.

The third is the knowledge engineering model. This is what my Dad was doing in the 1980s, engineering a system out of the expertise of experts and making it available for non-experts to use.

There is the communities of experience model. We are all familiar with social communities, things like Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter. We are familiar with professional online communities – something like SERMO, which is a network for doctors to share their experience. What is quite interesting is the emergence of what we call communities of experience, communities of recipients, patients, clients, students, coming together online, without any traditional professionals, to share their expertise with each other. So, Patients Like Me is an online collection of 350,000 coming together to share what treatments worked for them and how they coped with different symptoms, still producing and sharing expertise, but a very, very different model and one that does not revolve around traditional professionals.

The embedded knowledge model. The best way of thinking about this is the game Solitaire. Now, if you had played this game 15 years ago with a deck of cards, and you tried to put a red 5 on a red 6, what would happen? Well, you could do it but it would be called cheating. I do not know why you would do it. Now, what happens if you play on your phone and try and put a red 5 on a red 6? The red 5 whips back from where it came. The rules are embedded in the system, and it is an inevitable consequence, as more and more of our lives become digitised, as more and more of our activity is digitised, that the rules, the expertise, will be embedded in those systems, in the infrastructure that we interact with, rather than having a human being interject at all these various stages. A nice example, playing golf last year and drove past a sign that said “Caution – children playing” – the car slowed down. It was not possible to go above a certain speed. The rules, the expertise, the rules of the road were embedded in the system, and we will see that becoming more and more commonplace.

Finally, and this is the one that I think you see a lot in popular commentary in the future of work, there is the machine-generated model, systems, AI systems that both produce and share expertise, seemingly without much human involvement at all, and while that is part of the story, and it will become more of a story in the future, it is important to remember I think that the story is even more diverse than that and that the models for producing and sharing expertise, that technology is allowing us to develop, are not simply that final case.

So, what should you actually do, having heard all of this? This is something that many young professionals but also many existing professionals ask, and I think this is what you should not do, which is hope you can hold out until retirement before any of this stuff engulfs you. I think that is a mistake. We live at a really remarkable time of technological change, and I think, for traditional professionals and traditional providers of all these different types of practical expertise, I think the future can be a very exciting one, if you are agnostic about the particular ways in which you solve these problems. If you are of the mind-set that the only way to solve a legal problem or solve a medical problem or solve an accounting problem is to do it the way that your parents or grandparents did it, I think the sort of things that I have been describing are quite challenging. But if, instead, again, you are open-minded and agnostic, then I think it is an exciting one.

The second thing to say is that a lot of what we have said today has been from the standpoint of providers, talking about lawyers and doctors and teachers and accountants, and actually, from the point of view of recipients of professional work, I think the sort of things that we are describing, again, can be very exciting. Remember, just going right back to the start, those traditional professions are creaking, and if, through technology, we can find new ways to make the sorts of expertise that is, for many people, been unaffordable and inaccessible in the past, if we can find new ways to make it more affordable and more accessible, then I think, again, I think that is another reason to be optimistic and excited about these changes.

© Richard Susskind and Daniel Susskind, 2017

This event was on Thu, 30 Mar 2017

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham College plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login