Words and Pictures: Mixed Encounters

Share

- Details

- Text

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

This beautifully illustrated lecture explores the connections and interactions between British writers and artists.

As children, learning to read, we look first at the pictures in books - they tell the tale in their own way. With great writers, this power endures: artists connect with words in different ways. This lecture will explore fascinating examples of the relationships between artists and writers, from those that work independently from one another, such as Wordsworth and Thomas Bewick, to those that work very closely throughout the creative process, such as Dickens and Phiz.

This lecture touches on a peculiarly British tradition of community and defiance of authority, unmasking pretension and celebrating energy and warmth, linking daily life to the universal and the sublime.

Download Text

Words and Pictures: Mixed Encounters

Jenny Uglow OBE

This talk is an overview, not of a particular tradition, but of satire and book illustration in general. I was very interested, because of a personal, rather than an academic interest, in the way that words and pictures often go together. Also, I was very interested in the way that children start to look at books. Of course, they look at the picture, but they very often learn the words, almost off by heart, so they turn the pages, if it is a fairy story, and say “Once upon a time, in a country far, far away, there was…” and then they look at the picture and tell the story. I think this is an ancient way of reading and of imagining narrative. Therefore, today I will talk about three really different ways that artists have responded to text.

One is the way that artists illustrated Milton - both book illustrators and then people who we think of as independent artists. The second is not an artist responding to a text but an artist and writer working together, such as Hogarth and Henry Fielding. The third is one which is so obvious that we take it for granted, and was mentioned in the introduction, which is where the writer commissions an artist, and the artist is often so brilliant that they create the images that the reader sees. I will discuss whether there is any tension in that kind of work.

I love Edward Lear, and although I will not talk about the case where the writer and the artist are the same person, I saw a picture of the Owl and the Pussycat, which is relevant to the theme of words and pictures. The words are: “…went to sea in a beautiful pea-green boat. They took some honey and plenty of money, wrapped up in a £5 note.” In the picture, on the jar, Lear chooses to use the word “honey”. This picture would have had an altogether different feel if he had chosen to write “money”! It would have been distinctly less romantic.

The other important point to make about this whole tradition is that it is so ancient. The earliest illustrated book, narrative, or instruction manual that we know of, was the Egyptian Book of the Dead which is much in the news at the moment. In one of the weekend newspapers, there were great illustrations from that, and that was where the pictures actually had a sort of spell, in that they illustrated the things that the soul would need in the afterlife. So the picture was the image, and it is almost inseparable from religious texts from the beginning. People want to see, or teachers or preachers want to use an image that will convey the message that they are trying to get across. These could be frescos on the walls of churches and things. Also that illustration itself is a kind of worship. It is a way of making the text beautiful.

We, in the West, and in this country, have this marvellous tradition of illustrating manuscripts, and one of the ones that I love particularly is the Luttrell Psalter. It is similar to misericords in cathedrals where the illustrations do not seem to have much bearing on the words at all. However, the Luttrell Psalter shows the life of the English land through the seasons and it has the effect of relating the psalms absolutely to the lives of the people to which they are addressed while also being particularly beautiful. Some of you might have been watching Mike Woods’ television programmes about the history of England through a Leicestershire village, and all the little scenes that they showed of farming in the middle Ages came from details in the Luttrell Psalter. This is a kind of work where the artist is responding with two or three kinds of love and involvement: one with the text and the spiritual dimension; the second with the sheer beauty and elaboration of making a page look wonderful; and the third with an idea that they really want to record ordinary things that are going on. So, you have that kind of tradition of illustration.

Another, equally old, tradition is that of instructions, manuals, technical books and herbals which are things where you need to see what you are talking about. It was Leonardo who said, “The more minutely,” and we’ve all probably tried to do this, “you describe things in words, the more you will confine the mind of the reader.” It becomes immensely complicated and technical if you are trying to describe the relationship of details, “…and the more you will keep him from the thing described, and so it is necessary to draw and to describe.” Therefore, those two senses – the sheer enjoyment and the conveying of information – make the illustration important.

I have been working recently on the Restoration, and it astonished me that, within a couple of years or even written at the same time, two completely divergent, great British classics were produced. Both of them were in a sense spiritual works, and they were Bunyan’s “Pilgrim’s Progress”, and Milton’s “Paradise Lost”. They were both written under intense pressure during the Restoration, and represent completely different traditions: one simple prose, addressed to the ordinary people; the other, grand poetry, always thought to be more difficult, Latinate, a huge imaginative scope. When you looked at how they were illustrated, you saw these two traditions of literature, but also sort of diverging in different directions.

Robert White’s lovely portrait of Bunyan was the frontispiece to the third edition of “The Pilgrim’s Progress”, and it is thought to be really quite an accurate portrait of Bunyan. It tells the story of Christian, with the burden on his back and a book in his hand, walking up the hill towards the heavenly city on the top. Mysteriously, and this is not actually in “The Pilgrim’s Progress”, beneath the dreamer – “The Pilgrim’s Progress” begins, you know, “In the middle of the life, I dreamed a dream and I saw Christian,” so it is about the imagination and the vision of Christian - there is this strange lion. It depicts White and it is drawn as if all the passions and all the dark feelings, which Bunyan certainly does describe, are there beneath the dreamer. This was quite a sophisticated print, but still very direct and very simple.

The “Paradise Lost” ones, originating from about 10 years after, seem to come from a completely different tradition. One shows the wonderful moment when Satan is summoning his legions, prodding them to rise up, and he said, “On that inflamed sea, he stood and called his legions – angel forms, who lay entranced, thick as autumnal leaves that strow the brooks in Vallombrosa, where the Etrurian shades high over-arched embower.” It is a dark moment, and the souls on the floor of the sea do look a bit like autumn leaves.

However, there was something odd about this, in that Milton certainly never tells us that Satan is garbed in Roman costume as he is in the illustration. Also, when you look at it, he looks as if he is punting. Indeed, he is, because this was a commercial proposition. The publisher wanted to do a high-class, beautiful edition of the great classic, and so he hired his artists to do the illustrations. Reading Milton, it i hard to know where to begin describing what he says. How do you represent autumnal leaves, strowing the brooks, Vallombrosa, etc?

So the artist looked at other illustrations, and for the aforementioned image, as has been pointed out, the figure of Satan actually comes from a 1560 engraving, completely different, by Van Heemskerck, which is of Charon, rowing the souls across the Styx. It sort of fits, but not completely. It set a tone though for Satan, ever after, to appear in this Roman gear.

“Paradise Lost” was very popular to illustrate as it was grand, and there was a particular boom, a vogue, at the end of the 18th Century, and Milton becomes adopted as a national epic poet. All his republicanism was suddenly forgotten. During the Napoleonic Wars, there were about 60 editions of “Paradise Lost” between 1780 and 1825. He was terribly important to the poets as well as to the artists, and Wordsworth wrote this wonderful sonnet, where he said he felt faint when he read the description of Satan, from a sense of beauty and grandeur - this grand form was very important. He called on Milton. He said, “Milton,” he said, “England hath need of thee. We are selfish men. Oh raise us up, return to us again.”

This heroic Satan is the one that many chose to illustrate, and among the painters and artists of course, the artist who responded most strongly perhaps to “Paradise Lost” was William Blake. I could show you lots of other Miltonic illustrations, but just today, I am focusing on one or two. Blake uses a Michelangelo-esque figure to show this heroic Satan summoning his legions. He is not depicted as prodding them in this version. He is saying “Raise up, raise up” and he has lost his garb altogether. He is a grand, naked, malign energy of the world. So Blake made it much more dramatic, a much more bodily poem, and he does the same with his wonderful “Temptation of Eve”, where the serpent is entwined around her. He did two sets of illustrations, 12 watercolours in each, but they never actually were applied to the book. So this is moving out again – this is not an illustration. This is the artist responding to the text, and he can be less restrained.

Blake, interestingly, also looked back at Bunyan. Whereas illustration of Milton had become more grand, more smart and increasingly beautifully engraved, Bunyan’s “Pilgrim’s Progress” had become a popular favourite, hawked around the country by peddlers in their baskets, as a sort of chap book, and the illustrations had become very crude and very formal, and they often took exactly the same shape. In fact, there were always 14 illustrations. When Blake looked at it, he did his own little set, and he did them small, so it seems that he hoped that they would be actually used in a book, but they never were, and we do not often see them. They were extraordinary, because they were much tougher and cruder than the delicate and elaborate Miltonic ones.

There was a distinction between the classical high-art Blake and the popular, speak directly to the people Blake. One shows Christian at the wicket gate, and the little wood cut always shows Christian coming up and knocking on the gate, still wearing his rags. He has not been given celestial raiment. Another shows Christian meeting the fiend, Apollyon, who also is like a chap book figure, a figure from fairytale and legend, a sort of mythic beast, with his wings, his scales and his dreadful dart. It is a very dramatic picture too, because the accompanying words are: “Then Apollyon,” Bunyan writes, espying his opportunity, began to gather up close to Christian,” Blake pushes Christian so close he is almost embracing Apollyon, “…and wresting with him gave him a dreadful fall, and with that, Christian’s sword flew out of his hand. Then, said Apollyon, “I am sure of thee now,” and with that, he had almost pressed him to death, so that Christian began to despair of life.” The way that Blake – we do not even need to hear the words - shows Christian, rising up, you know that, somehow, this frail man is going to defeat this foul fiend. This kind of illustration is very direct, and the kind that I went back to, unlike the Miltonic ones, where anybody looking at the book or being shown the pictures would be able to tell the story to themselves.

So, that is just one example of artists, a particular artist, Blake, responding to text, and following different modes, just as there are different modes of literature, the classical and the popular. Then, I looked at another pair, and thought of Hogarth, one of my favourite artists. Hogarth also, in his sort of high art mood, had actually done an extraordinary painting in connection with “Paradise Lost”, which is of Satin, sin and death, and that was enormously influential on these sorts of artists. However, the people who read Bunyan, the prints of Hogarth that they would know would be things like the idle and industrious apprentice, or the four stages of cruelty, the teaching works and the satirical works. I know some of you will have heard people talking about satire recently, and that fits with the satirical tradition as well.

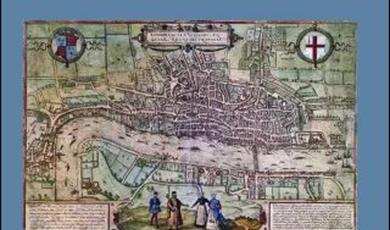

These two really were good friends and they were very different. Fielding was aristocratic, well over six foot, always shabbily, elegantly dressed, known for a long velvet coat, which he covered in snuff, which he pawned all the time, and then he would get it out of the pawn shop for a first night of one of his plays or something like that. Hogarth was only five foot, and he was not a Cockney, but he was born just round the corner in Smithfield and was a stroppy, strutting, pugnacious, hard-looking bloke. Yet, they were great friends, and if you imagine them walking round Covent Garden together, you think what an odd pair they would be.

This is Hogarth’s frontispiece to the works of Fielding, 1762, eight years after Fielding’s death. Fielding died young in Lisbon, seeking for fine weather and health. Hogarth has shown us, just in the illustration, what kind of man he wishes us to remember. He is shown as a magistrate: he has his law books, the scales, the sword of justice and the pen; but he is also the dramatist, with the masks, and the author, and above that, on the side of the book, it says “Jones”. We are all supposed to know it says “Jones” – actually, it just says “ones”, because everybody is supposed to know, “Oh, there’s Tom Jones!” So it is an affectionate yet dignified treatise.

They started out together. They were both young men who were influenced by John Gay’s “Beggar’s Opera”, which was put on in 1728, which turned the whole of the polite world upside down. It showed the adventures of Macheath, the jailors and the thief-takers, and everybody could make a connection between the highwayman on the stage and Walpole in power, and yet you could say, “No, no, no, it’s not satirical – it’s just good fun!” and that is very much what Hogarth did too.

His first really successful series of prints was “A Harlot’s Progress”, and in one, we can see young Moll Hackabout, arriving in town, as an innocent girl, from York, but we know that she is being rather foolish. We see the silly goose with its head over the side of the basket, and she is being chatted up by Mother Needham, a notorious bawd in Covent Garden, while the clergyman, on the horse behind, turns his head, looks the other way, even though all the buckets are falling down. Terrible things are happening, and the real villain in the piece is lurking in the doorway behind, Colonel Charteris, who was a notorious seducer and even rapist. He had just been tried for assaulting a maidservant and acquitted because he had so many friends in power. When Charteris died just shortly after the trial and just before the prints were published, the people of London gathered and hurled dead dogs and cabbages and anything they could find into his grave. Again, however, Hogarth could say: “ Ah, what do you mean, Colonel Charteris?” and because Charteris is close to Walpole, it is also saying that they are the real villains that everybody is being procured to – they are the people that are actually sort of raping and assaulting us, but he did not really need to do that explicitly.

Fielding, at the same time, was doing his own “Beggar’s Opera”. He had gone off to Leiden to university, come back to England, and before he wrote his novels, he put on these wonderful irregular dramas, which is the little satirical play after the main play. One of these was called “The Covent Garden Tragedy”, and he turned a classical drama upside down. His prologue said exactly the same thing: he was going to do just what Hogarth had done, this was the same time, and instead of showing people in Greece and Rome, he said that he was going to “From Covent Garden, cull delicious stories of bullies, bawds and sots and rakes and whores, examples of the great can serve but few, for what are kings and heroes’ faults to you? But these examples are of general use – what rake is ignorant of King’s coffee house?” That is his audience, and Hogarth’s audience was the same, and they used that London world to satirise the great.

They were both particularly interested in the idea of the mask and the person. “Tom Jones” was very much about finding out who was true or false; who was sincere or insincere; and who the hypocrite was. This is just what Hogarth’s was doing. Fielding had a magazine called the “Champion”, in which he wrote: “In his excellent works, you see the delusive scene exposed with all the force of humour, and on casting your eyes on another picture, you behold the dreadful and fatal consequence.” The rake, and indeed Moll, both come to terrible ends, so people could always pretend that these stories were real, serious moral tales, whereas actually of course, the fun was the high jinx they got up to on the way there.

Fielding went on: “I almost dare affirm that those two works of his which he calls “The Rake’s and the Harlot’s Progress” are calculated more to serve the cause of virtue and for the preservation of mankind than all the folios of morality which were ever written, and a sober family should no more be without them than without the whole duty of man in their house.” I heard someone chuckle and that is right – this was completely tongue-in-cheek, because Fielding was actually writing in the persona of Captain Vinegar here, and he dids not really expect a sober family to have “The Harlot’s Progress” on their kind of hall wall as people came in, and said, “Oh look what lessons we are learning from this!”

They continued to work together. Hogarth called his prince of drama a dumb show, in which the men and women were his actors, and Fielding constantly refers to Hogarth and says he wants Tom Jones to be like the work of a certain comic history painter.

Of course, they later worked directly together. They worked together all the way through. In 1748, Fielding became a magistrate. He left the theatre in the late-1730s, when Walpole shut down the irregular playhouses, and then he wrote his novels, which also included an attacking journalism. In 1748, he became a magistrate at Bow Street which was not far away. He was a very fair, compassionate magistrate who was very concerned about the condition of the poor. He wanted MPs – we could do it today – to actually go into the houses of the poor, judge the conditions and not just pontificate from Westminster.

He felt that a lot of the misery of London, in particular, was due to the sale of adulterated gin, which literally rotted the minds. He was campaigning to have the Gin Act introduced, which would licence the sale of gin. He did not want, as it were, to take away the tipple of the poor, whilst the rich could have their claret.

To help him, Hogarth produced two companion prints: Gin Lane and Beer Street. Beer Street shows a fairly sort of happy, prosperous nation, where the houses are going up, and here he really uses his art to campaign. As in all Hogarth’s work, at every corner, something is going on. There are the little charity children, with the cross on their back. They are very concerned about the next generation. The workmen who are pawning all their tools, life is going so slowly that a snail can even crawl up somebody’s arm, and of course, in the middle, the ballad singer is starving and is dropping his ballads. But worst of all, the female figure in the middle, who could be Britannia or could just be an ordinary woman from the slums of St Giles, is not throwing her baby into the abyss, she is just letting it fall, which is almost worse - she just does not know what is happening to her child which is what Hogarth said had to be stopped. If you think of it from an artistic perspective, all the angles, all the lines and all the collapsing houses are attacking each other, and the whole way that the perspective of the print goes is that it is as though there is no foreground and that if the audience is not careful then they will fall into that abyss too.

They were effective working together, and the Act was introduced. Hogarth never let his own art become an illustration of something. He produced the pictures and images that he wanted to in his own way, and similarly, Fielding’s prose was really new and different. They learnt from each other and worked alongside, so that was quite a remarkable encounter between an artist and a writer, and very different to, say, the illustrators of Milton or Bunyan, or even Blake, who was responding to a text that had already been written.

I will now look at the third kind of encounter that I intended to mention today. It follows from a talk you had on book illustration for in the 19th Century book illustration really took off.

This scenario is when one of the artist and illustrator was actually commissioning or choosing the other. Very often, they were instructing or telling them what they wanted to see, not necessarily “Here is the story - you illustrate it”. It was a much more intimate, personal relationship.

I began by thinking about children’s books, and then particularly thinking about Alice, which was a topsy-turvy world of a very different kind to Gin Lane. Lewis Carroll actually began writing his fairytale for “Alice” in November 1862, and he chose Tenniel to illustrate it not because he was known as an illustrator of children books, but he liked his illustrations for Aesop’s Fables and for Punch. He liked his sort of satirical edge. Tenniel was far more famous than Lewis Carroll, and so it was the illustrations that first caught the artist’s attention.

For example he did an illustration of the caterpillar, with his hookah, and the wonderful White Queen.

However, Tenniel was not free – Carroll had done his own manuscript illustrations, and Tenniel followed a lot of them quite precisely even if he did draw on his own background and use models from his satirical work and from other people as well. There is a lot of borrowing in illustration, and it is usually not seen as plagiarism. It particularly happens with cartoons, and it is seen very much today: Steve Bell or Martin Rose say “After Hogarth” or “After Gillray”. It is as though they are talking to their forbearers.

The Tweedledum and Tweedledee which Tenniel created, were versions of his own John Ball, and the caterpillar, with the hookah, John Leech, who was another illustrator of the day, had done a cartoon of the Pope as an oriental potentate, so there was a different little joke in there. People would remember Leech’s Pope.

It was not an easy relationship because Carroll checked absolutely everything and Tenniel got very fed up and dismissed him – he called him “a conceited old doyen”, and he refused to illustrate “Through the Looking Glass”, but then Carroll could not find anybody else. I am not sure whether word had gone round saying “Do not work for that man!” but in the end, Tenniel agreed.

Despite this, they were very much his pictures. It was an odd fusing of brilliance. You would think, from this, that artist and writer got on absolutely perfectly, but I think that that tension enabled Tenniel to make us feel the kind of pressure that Alice was under. One of the most brilliant illustrations was engraved by the Dalziel Brothers, who have been mentioned in earlier lectures. It shows her shrinking and growing and her arm just going out of the window. It is a frightening illustration. It comes from one of Carroll’s own conceptions, and yet it is made extremely powerful. It takes the reader beyond the realm, as the whole book does, of the children’s tale.

However, whereas it seems fine for us now, we are still very used to children’s books being illustrated, whereas we do not have illustrations in our adult novels. We do, thank goodness, have actually a new tradition growing, year by year, which is that of the graphic novel – a slightly different concept - but in Victorian England, adult novels were really illustrated, especially as the print technology allowed them to carry more illustrations. Many authors absolutely hated it. Frederic Leighton illustrated “Romola”, and George Eliot exclaimed “It’s not my Romola – I can’t see it!” Henry James was deeply distressed when photographs were integrated into his work. James particularly was part of the next generation, because the big vogue had, by that time, begun and that vogue was very much began with Dickens.

Of course the illustrations of Dickens are another of my favourite sets of illustrations. Dickens was absolutely soaked in the world of prints. He was a great admirer of Hogarth, of Rowlinson and of Gillray, and he used this. Oliver Twist’s subtitle is “A parish boy’s progress”, which takes you back to Hogarth’s “Harlot” and the “Rake” and to Bunyan’s “Pilgrim’s Progress”. That is a particular kind of story. And he once told John Forster that he did not invent his stories. He said: “Really do not, but see it, see it,” underlined, “and write it down.” So, there was a slight problem here, in that he wanted his readers to see his stories, but just the way that he saw it. He wanted an illustrator that he could work so closely with that they almost could see it together. He specified the scene, he specified the characters and he told his illustrators exactly what he wanted - even their gestures and the furniture!

“Pickwick” was supposed to be a book which followed the illustrator, which is an idea of the illustrator Robert Seymour, who suggested a series of visual scenes, of sporting life and Cockney wit, and so the publishers, who were Chapman & Hall, set out to find an author. Several writers said no, and then this young Dickens, who was 24, said okay, but he knew what he was from the very start. He insisted that he was not going to follow the illustrations; the illustrations must follow the text. Not because of that, but shortly after, Seymour committed suicide, and there was a great hunt for a replacement, and eventually they found another young man, this 21 year old engraver, Hablot Knight Browne. He signed his first work “Nemo” - no one – he thought that he would be obliterated by Dickens before he realised that he could match Dickens. Dickens was known as Boz, so Hablot Knight Browne became Phiz, and so that amazing partnership was born.

This is an illustration from “Pickwick”. This shows Mr Winkle’s situation when the door flew to. This, as you can see, is taken from a little OUP illustrated edition – but it is still absolutely clear, because the composition is so good. The effort behind one illustration was considerable – it required lots of going back and forth between author and illustrator. Dickens would always comment on the design – he wrote little notes around the side, and then Phiz would write his notes back, and so on. For example, with this image, Dickens said, on the first draft, and this was after Phiz has followed his instructions: “Winkle should be holding the candlestick above his head I think,” which is what happened. “It looks more comical, the light having gone out.” So he is shown holding this candle, without a flame, over his head! Dickens says about a fat chairman that “So short is our friend here, never drew breath in bath” – he loved the short fat person who is supposed to be carrying a sedan chair. “I would leave him where he is, decidedly. Is the lady fully-dressed? Is she fully-dressed? She ought to be.” Phiz wrote back: “Shall I leave Pickwick where he is?” Now, Pickwick is in the first-floor window. In the text, he was in bed. If he had been put under the bedclothes, he would have been invisible. “I can’t carry him so high as the second floor,” wrote Phiz. Now, that was the composition speaking – if he took it up higher, the actual action would be squished, so Dickens, obligingly – he often did alter the text for Phiz – brought him down a flight and put him in a bedroom on the first floor instead.

Dickens wrote about everything, even facial expressions, like Sergeant Stubben, who does not appear in this image but does so in other Pickwick Papers. Imagine being an illustrator and having to follow instructions like this: “He should look younger and a great deal more sly and knowing. He should be looking at Pickwick too, smiling compassionately at his innocence.” So Phiz had to imagine it, as he brilliantly does, sort of from the inside, so that that little tiny expression Sergeant Stubben’s face would make him look young, sly, knowing, and understanding Pickwick’s compassion.

Although Dickens was already dealing with Cruickshank on “Oliver Twist”, after that, he and Phiz set off for Yorkshire to find the models for Dotheboys Hall, and again, it was Phiz who drew the two brothers who became the Cheeryble brothers, and Dickens wrote them in.

They worked together for 20 years. They did “David Copperfield”, “Dombey and Son”, “Martin Chuzzlewit” “Bleak House” and “Little Dorrit”, and it was becoming harder and harder for Phiz, as Dickens’ prose became more elaborate and so detailed that it was almost beyond the reach of illustration.

For “Little Dorrit”, the usual notes kept coming: “Mrs Plornish is too old and Cavalletto a little bit too furious and wanting in stealthiness.” Phiz dealt with it brilliantly, particularly with the comic elements, as he had with the wonderful Micawbers from “David Copperfield”, a truly sort of joyous mid-relationship book. The caption is very good too: “Restoration of mutual confidence between Mr and Mrs Micawber”!

This is a priceless illustration from “Little Dorrit”. It shows Mr Flint, which has a bad attack of irritability. He is shown nearly shaking her to death, and there is this terrible little imp behind, coming up behind and there is our wonderful, melodramatic villain, swathed in his black cloak in the shadows.

So, he could do that, but the gloom of the novel I think was sort of too much for Phiz, who had done some almost completely black prints for “Bleak House” to fit the mood, and had been much mocked because of it, and so they parted. Dickens wanted a new style, and Phiz began working for others too. Their last work together was “A Tale of Two Cities”.

However, I think it is a magic subject, the relationship, both between artists and texts, and artists and writers, in all their different ways. Dickens wanted people to see the story as he saw it, but I think actually, for generations, people saw the story as Phiz saw it.

Just to end, I want to sort of zoom up to the present really, and back to the first subject, which is an artist responding to a text. I think that you can have this other kind, which I have not really talked about, which is another dimension again, where the artist’s work is both a brilliant response to a poem, as Blake’s was, and a perfect illustration as well.

This is Mervyn Peake’s illustration of Coleridge, the albatross, which is an extraordinary image and terrifically modern. It is an image of the 20th Century, of that terrible, fateful Century, and yet, it is also a perfect illustration of Coleridge’s rhyme of the “Ancient Mariner”.

So, I hope that has given you just a little glimpse, not necessarily of the subject, but of the kinds of things that I think are fascinating, and you can doubtless find many more of your own

©Jenny Uglow, Gresham College 2010

This event was on Mon, 25 Oct 2010

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham College plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login