Press release: Slavery and the British Economy

Describes brutal punishment and regime of terror during slave trade

Concludes 1833 ‘abolition’ happened despite slavery still being profitable

Atlantic slave economy had a role in the development of the British economy, but was not alone responsible for industrial success

Embargo: Tuesday 7 Feb, 7pm

We would like to invite you to a Gresham lecture by Professor Martin Daunton on Slavery and the British Economy. Economic historian Daunton, who is Emeritus Professor of Economic History at Cambridge University, has worked as a Commissioner for Historic England and was involved with the implementation of the policy of "retain and explain" of contested heritage.

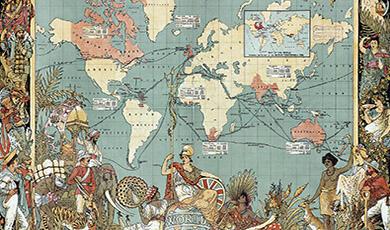

In the lecture, Daunton will look at the brutal nature of the slave trade, “degraded and debauched…hell on earth”; he will examine the evidence for slavery being key to Britain’s industrialization and success. He will say that on balance:

“It is right to put the Atlantic slave economy back into the development of the British economy. There is also a danger of exaggeration which has entered into public discourse… such exaggerated claims play into the hands of opponents of so-called ‘woke’ culture. We need to counter them with careful historical analysis.”

However, he will say, “The scale of the slave trade and economy was not larger than many other sectors,” that there is “no evidence sugar/slavery more directed to industrial investment than other sectors,” and that ultimately much of the money from slavery went into funding/creating gentry families by purchasing landed estates and conspicuous consumption rather than into industrialisation.

Slavery, Daunton will argue, was still profitable in 1833 when it was rejected inside the British Empire, though not in India, but that, broadly, humanitarian arguments plus the domestic political tensions over parliamentary reform and demands to remove support for expensive slave-produced West Indian sugar, won out.

“Abolitionists came to accept that they could condemn slavery and uphold property rights that were in conformity with law as it had existed. One Liverpool abolitionist commented in 1826 that ‘it would be robbery, under the garb of mercy, to compel one class of individuals to atone for the injustice of a nation’. Rather than a few criminal individuals who deserved to lose, it was admitted that the nation as a whole was at fault, and that many individuals who stood to lose were not complicit.”

So did the money for compensating slaveowners for the end of slavery go towards industrialisation? Daunton finds some evidence for this particularly around building the railways. However:

“About half of the compensation went to non-British residents in the colonies – and a considerable part of the compensation to British residents went abroad , especially to US railways and cotton states, and to Brazil – much of it into the slave-based economies. The result was a drain of bullion overseas that helped cause a financial crisis in 1837.”

He will say: “To criticise those who try to work through these arguments as ‘woke’ is to misunderstand British history. These issues were debated by contemporaries and deeply divided opinion – to say that analysis undermines our common heritage ignores the reality that our history was always contested.”

ENDS

Notes to Editors

You can sign up to watch the hybrid lecture online or in person; or email us for an embargoed transcript or speak to Professor Daunton: l.graves@gresham.ac.uk / 07799 738 439

Login

Login