The General Election, 1979

Share

- Details

- Transcript

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

The 1979 election inaugurated the premiership of Margaret Thatcher, the longest continuous premiership since that of Lord Liverpool (1812-27), and an 18 year period of Conservative government. It occurred after the 'winter of discontent', marked by public sector strikes which destroyed the Labour government's social contract. James Callaghan, defeated Labour Prime Minister, declared before the election that it marked a sea-change in British politics. Was he right?

Download Transcript

10 March 2015

The General Election, 1979

Professor Vernon Bogdanor

Ladies and gentlemen, this is the fourth lecture in the series on significant General Elections since the War, and this is on the 1979 General Election, which saw the largest swing since the War, a swing of over 5%, although it has been exceeded since, and it inaugurated eighteen years of Conservative rule, the longest period of single Party rule since the time of the Napoleonic Wars, and eleven of those eighteen years were dominated by Margaret Thatcher as Prime Minister. But it was more than a shift of parties, it was arguably, in 1979, the end of an era because it heralded a change in the role of the State and a new view of what the State should be doing, and it also marked the end of what can be called the post-War settlement.

Now, what do I mean by the “post-War settlement”? What I mean is that, after 1945, some issues in politics seemed to be completely settled and closed, so that no one was prepared to open them - for example, that there should be a mixed economy comprising a nationalised sector, public sector, and a private sector. That was agreed by the Labour and Conservative Parties until 1979. That there should be full employment was generally accepted until 1979 and no party dared break from that consensus, and that full employment should be secured by broadly Keynesian policies of demand management and fine-tuning of the economy. That was also agreed by both parties. Both parties had come to agree, from the time of Harold Macmillan in the early 1960s, that to secure full employment, you needed an incomes policy, either a voluntary policy agreed with the trade unions or a statutory policy, and that to complement that, most major items of policy, particularly domestic policy, there should be discussions and consultations with the trade unions, which were an estate of the realm, and both Labour and Conservative Governments agreed with that. This was a legacy of Ernest Bevin’s time at the Ministry of Labour during the War, and that was the consensus. It is now, as you all know, all gone - we do not have a nationalised sector anymore, or a very small one. Full employment, as it was understood up to 1979, has gone. Full employment was understood as a level of unemployment higher than 3% - that is gone. Keynesian policies of economic management and fine-tuning have gone, and of course incomes policies have gone. The last one was by the Callaghan Government which was defeated in 1979. I think no Government now would dream of an incomes policy. And I think even if a Labour Government is returned in the Election this year, they will not be involved in very close consultation with the unions of the type that used to exist.

The collapse of this settlement is generally attributed, and not unfairly I think, to Margaret Thatcher, but it was heralded by the Labour Government that preceded her, and in particular by a speech made by James Callaghan, as Prime Minister, to the 1976 Labour Party Conference, in which he seemed to be repudiating Keynesian measures of demand management. He said this: “We used to think that you could just spend your way out of recession and increase employment by cutting taxes and boosting Government spending. I tell you, in all candour, that that option no longer exists, and that insofar as it ever did exist, it worked by injecting inflation into the economy, and each time that happened, the average level of unemployment has risen – higher inflation, followed by higher unemployment. That is the history of the last twenty years.”

In the early 1980s, the Conservative Chancellor of the Exchequer, Nigel Lawson, was to say that post-War Governments had made a mistake in trying to control unemployment by Keynesian methods and to control inflation by microeconomic methods and incomes policies. He said they got things the wrong way round. He said they should deal with inflation by macro measures, primarily control of the money supply, and then the exchange rate, not by incomes policies - and Margaret Thatcher was in fact the first Prime Minister since Anthony Eden not to have an incomes policy – and that the way to secure higher employment, though perhaps not full employment, was through supply side policies, increasing the efficiency of the market, and that is broadly the system under which we now live, and the aim was to get unemployment down through trade union reform, greater labour market flexibility, and better education and better skills. So, 1979 also was to mark the end of the post-War settlement.

More specifically, it marked a crisis for the Labour Party and for social democracy, and in 1978, rather presciently, a year before the Election, the Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm, who was in fact a member of the Communist Party, wrote a pamphlet called “The Forward March of Labour Halted”, and that was to be the result of the 1979 Election, that the whole idea of consultation with the trade unions went, and the whole idea of an organised working class working with the Labour Party went as well. It was a crisis for labour, and socialism no longer seemed, as it had for much of the twentieth century, the wave of the future.

Just before the twentieth century, in 1894, a Liberal Chancellor of the Exchequer, Sir William Harcourt, first introduced death duties, and in response to criticism, he replied, “We are all socialists now.” In other words, everybody believed in a much greater degree of State intervention. But you may say that what happened in 1979 showed the need for reform of the Labour Party and Tony Blair’s New Labour so that Labour could only get back in 1997 by saying “We are none of us socialists now…” So, I think that 1979 is a highly significant Election, a watershed between two eras.

Now, the last election that I discussed in my lecture, February 1974, the outcome, a Labour victory, a narrow Labour victory, surprised many people and was arguably determined by the campaign. It was a highly uncertain Election, as of course the one this year is being – I think anyone who predicts it is being rather foolish. I think it is the most unpredictable election we have had – I think it is an election that is not possible to predict, though I am not certain of that prediction…

[Laughter]

But the 1979 Election was not a surprise. Almost everyone thought the Conservatives were going to win – it confirmed what people thought. And the causes of the Conservative victory lie not in the campaign itself but in the history of the previous five years and, in particular, the six months before the Election.

A Conservative victory had not seemed likely when Labour took office as a minority government in March 1974, defeating Edward Heath, and the Labour Party went to the country in October, it was just seven months of the Parliament, and secured a very narrow majority of three, a narrow overall majority of three, and that Government was led by Harold Wilson. But in April 1976, Harold Wilson retired, and was succeeded by James Callaghan, but at the same time, that Government had become a minority government due to by-election losses and defections, and as you will see, the Scottish Nationalists did very well – they got 30% of the Scottish vote, which is higher than they got in 2010, when they got about 21% of the Scottish vote. They got nearly a third of the votes in Scotland, and the Welsh Nationalists also did fairly well. The Labour Government secured itself in office by offering the Nationalists devolution, the policy of devolution, and they secured the support of the Northern Ireland parties by promising to increase the number of seats in Northern Ireland from twelve to seventeen, which was reasonable because Northern Ireland had been under-represented while it had devolution, the Stormont system, and now it did not have devolution, it was ruled directly from Westminster, so it was reasonable to make the balance of seats in proportion to population. But that secured the position of the Labour Government.

Now, 1974 was a very traumatic year because, with the defeat of Edward Heath, it seemed to many that the control of trade union power was a central issue of politics, and many people were looking to the abyss and thought perhaps Britain was ungovernable, and even many in the Establishment thought that.

There was a remarkable episode towards the end of the Heath Government when Sir William Armstrong, the Head of the Civil Service, was found lying on the floor in his office, chain-smoking and screaming about the wold coming to an end, and he was led away for treatment. Heath’s Private Secretary rang up Heath, and said that the Head of the Civil Service had been locked up – those were the words he used. Heath said he was not surprised. He said he “…thought William was acting oddly the last time I saw him.” Sir William Armstrong had to retire early from the Civil Service, but in 1975, he became Chairman of the Midland Bank…

[Laughter]

But the Labour Party had an answer to this problem, which put the Conservatives on the defensive, and the Labour Party’s answer was the social contract, which was an agreement with the trade unions that they would agree to wage restraint in return for certain benefits which the Government gave them, and Labour said that would deliver peace and quiet and the only alternative was Heath and confrontation, that Labour would secure the consent of the trade unions, which was essential to running an advanced industrial society, whereas a Conservative Government would mean endless strikes and industrial upheaval.

Now, it seems to me Labour misunderstood the verdict of these two Elections in 1974, that although they had got a majority, they had not really won the Election – it was just that they had lost fewer votes than the Conservatives. You see, they had under 40% of the vote, which was unusual then. We have become used to it now. And there was no real basis for saying that Labour had a mandate for the social contract and more particularly for increasing the powers of the trade unions. Now, every single opinion poll during this period showed that the vast majority of people felt that the trade unions were not too weak but too powerful, and they wanted their powers restricted, but the Labour Party proceeded to heap new responsibilities, privileges and immunities upon the trade unions.

They, firstly, repealed the Conservative Government’s Industrial Relations Act. They restored all the trade union immunities that the Act had curtailed, and they gave new legal protection to picketing, so they gave the trade unions tremendous rights. They also put in law a statutory right to belong to a trade union, that everyone could belong to a trade union, but no corresponding right not to belong to a trade union, and they gave statutory force to the idea of the closed-shop. So, the unions had much greater powers, and the question was: what would the trade unions give in exchange?

The Chief Secretary to the Treasury in the Labour Government was Gerald Barnett, who died recently, and he wrote a book of reminiscences, a very interesting book on the period, called “Inside the Treasury”, and he said the social contract was “…a matter of give and take, and the Government gave and the trade unions took”. But that, I think, was not wholly fair because, in 1975, the trade unions did accept the need for an incomes policy for voluntary restraint, unlike Heath’s incomes policy which had been statutory, and that worked for three years until 1978.

Now, the Labour Party further strengthened its position in 1977 when it agreed to a pact with the Liberals. This would now be called a “confidence and supply” agreement, and it may happen after the next Election, that the Liberals did not join the Government but they agreed they would support the Government in all votes of confidence and in financial matters, supply, budget and so on, and this guaranteed the Government against defeat. They still had Nationalist support and they still had the support of the Northern Irish. Now, the pact ran out in the autumn of 1978 and there was a general assumption that there would be an Election.

After many difficulties, the economy was now beginning to improve. In 1975, inflation had reached the huge level of 26%, but it was now falling to what was thought of, in those days, as an acceptable level. In the summer of 1978, it was 7.8%, which was lower than France and Italy but higher than Germany. Opinion polls were also showing that Labour, having been a long way behind, was beginning to catch up with the Conservatives as inflation was falling, and Labour seemed to have another advantage because the new Conservative Leader was Margaret Thatcher, who seemed, at the time, inexperienced, and James Callaghan tended to defeat her in parliamentary debate and questions, and Margaret Thatcher’s main political ally was Sir Keith Joseph, who was proposing policies that many people thought would lead to much higher unemployment and industrial dislocation, and they thought he would be rather extreme. And the effect, you can see, when he became Secretary of State for Industry under the Thatcher Government, Michael Foot, who was at the time Labour’s Deputy Leader but then became the Labour Leader, made a brilliant speech showing the effect of Conservative policies, which they were also predicting in the 1970s.

We can hear Foot’s speech – we cannot, unfortunately, see him, but we can hear the speech…

[Recording plays]

“I would not like to miss out the Right Honourable Gentleman, the Secretary of State for Industry, who has had such a tremendous effect upon the Government and our politics altogether, and as I see the Right Honourable Gentleman walking round the country, looking puzzled and forlorn and wondering what has happened….I have often tried to remember what he reminds me of, and the other day, I hit upon it because I recalled that in my youth, when I used to go, in Plymouth – yes, I know quite a time ago…we will come to that one in a moment too – but I used to go, when I lived in Plymouth, every Saturday night, along to the Palace Theatre, and the favourite I always used to watch there was a magician conjurer, and they used to have in the audience, dressed up as one of the most prominent aldermen in the place, a person who was sitting at the back of the audience, and the magician conjurer would come forward and say that he wanted to have from the audience a beautiful watch, and he would go amongst the audience, he would go up to the alderman, and eventually take off him a marvellous gold watch, and he would bring it right back onto the stage. He would enfold it in a beautiful red handkerchief. He placed it on the table there in front of us. He took up his mallet, and he hit it, smashed to smithereens, and then, on his countenance would come exactly the puzzled look of the Right Honourable Gentleman….and he would step forward…and he would step forward [laughter]…he would step forward right to the front of the stage and he would say “I am very sorry…I am very sorry, I have forgotten the rest of the trick!” And that is the situation of the Government! That is the situation of the Government: they have forgotten the rest of the trick!”

That was the industrial dislocation which they were predicting, which some said did actually come about – higher unemployment and industrial dislocation from a Conservative Government.

In the summer of 1978, there had to be a renewal of the incomes policy, a stage four of the incomes policy – there had already been three stages. In a White Paper published in the summer of 1978, the level was fixed at 5%, and it was fixed at that level because that would mean inflation remained below 10%, and that was Callaghan’s own policy. Normally, he operated through the Cabinet; on this, he decided alone. It is not even clear whether his Chancellor, Denis Healey, supported him, and many in the Cabinet, particularly those responsible for the public services, did not because it meant a tightening of incomes policy after three years, when many of the trade union leaders thought it should be loosened. Callaghan did not consult with the unions. It was unilateral and imposed. When some of his advisors challenged him, as one of them wrote in a book, he said, “The normally equitable Callaghan went completely puce and hit the table and said, “Are you saying that 5% is not right for the country?”” What they meant was it may be right for the country but you will not be able to implement it. This policy was rejected by the Trade Union Conference in the autumn of 1978 and also rejected by the Labour Party Conference, but the rejection by the trade unions was seen as proforma because the general view was that Callaghan, at the Trade Union Conference, would be declaring a General Election. Here, too, Callaghan had this terribly lonely decision that you may remember, those who were here last time, that Edward Heath had to make: when was he going to have the Election?

Now, some polls, by September 1978, were showing the Labour Party a little way ahead. Callaghan said he did not trust them. Other polls said the best he could hope for was another hung parliament, and Callaghan said he was fed up with endless negotiations with Liberals and the Nationalists – and who can blame him. And he said, if it is a balance decision, if the best we can do is to get back with another hung parliament, let us wait and hope to do better later, and Callaghan thought, and perhaps quite reasonably, the unions would not cause too much trouble if they knew there was an election to follow later.

Well, he consulted quite widely and the whips were, on the whole, against an early election, by eight to three. Michael Foot, who was Leader of the House of Commons, said that MPs in marginal constituencies were rather nervous – they did not think things were going well, and he also said that Callaghan could continue after October with no danger of defeat because the Northern Irish were still waiting for their extra seats, and there was going to be a referendum on devolution on March 1st 1979 and the Nationalists would not get him out before then. Furthermore, there was going to be a new Electoral Register in 1979 which was worth about probably six extra seats to Labour.

The Cabinet favoured an early Election, though the members of it wanted to go on, and the point I am trying to make is that Callaghan, when he made his decision, it was a very lonely decision – he did take wide advice and opinion was divided. Now, he spoke to the Trade Union Conference in September 1978 and he teased them. He said, “The commentators have fixed the month, the date and the day.” He said, “Well,” he said, “remember what happened to Marie Lloyd,” a music-hall artist of his young. “She fixed the day, she told us what happened, it went like this…” and if the IT people can show us…hear James Callaghan…

“There was I, waiting at the church….

[Applause]

Perhaps you recall how it went on: “All at once, he sent me round a note, here is the very note, this is what he wrote, cannot get away to marry you today, my wife will not let me.”

Well, that was a very good joke, although the joke turned out to be on James Callaghan and not on anyone else. But the comedian Roy Hudd wrote to Callaghan and said it was not Marie Lloyd, it was Vesta Victoria, and Callaghan said he knew that but he thought that no one knew who Vesta Victoria was but some of the older people amongst the TUC would remember who Marie Lloyd was, so he sang that song.

Now, Callaghan decided he was not going to have the election in autumn ’79, and that meant there was no way to get out of the 5% commitment, and it may be the Cabinet would have rebelled more strongly against it if they had known there would not be an election. There were various difficulties with that 5%, that it meant, given the rate of inflation was higher, it meant a real fall in the standard of living for most workers, and the trade unions told Callaghan they could not hold the line – they could not deliver it.

Even worse, and here there is some signposts to today I think, the 5% did not apply to senior civil servants or the head of nationalised industries, nor to many of the managers in private industry. They used the argument they could not attract talent unless they paid a lot more than 5%. So, it seemed unfair, and perhaps particularly unfair to the low-paid.

Now, the trade unions felt they had been teased and cheated by Callaghan there, that he had deceived him about the election, and they were rather annoyed at being treated in that way, and they were now, as I have explained, much more powerful as a result of the legislation that Labour had introduced, in particular closed-shop. At that time, trade union membership was much more extensive than it was today. It reached its peak in 1979, with 53% of the labour force, and particularly strong in the public sector.

But the main problem facing Callaghan was the same one facing Edward Heath: the trade unions were not there to police wages in the interests of Government policy but to do the best they could for their members. If they did not, there would be a revolt on the shop-floor, and that is what happened, and when it came, it was militant and, on occasion, violent, and Callaghan could not deal with it. It was outside his experience. He had grown up in the shadow of Ernest Bevin and was psychologically unable to appreciate that the trade unions would not cooperate with Government.

Now, the leader of the Transport & General Workers Union said to Callaghan, “Who are you to say that my members cannot have the increase I have negotiated for them?” The answer, until autumn 1978, was it was TUC policy to accept wage restraint, but it was not after 1978 because the TUC had rejected it, and problems immediately arose with the Transport & General Workers Union, which was, at that time, the largest union.

The first problem arose in the private sector, just before Christmas, that, in the Ford Motor Company, the TGWU, the Transport & General Workers Union, put in a claim for 30%, and they said this was justified because the firm had large profits and the Chairman had just had a salary rise which was not 5% but 80%. Ford offered 5% in accordance with the Government guidelines, and there was then a strike which lasted for nine weeks, an official strike, and that meant, while this was going on, Ford was losing money of course to its competitors. So, they eventually settled at 17%, which of course was far beyond the guidelines of the Government, but became the going rate in the motor industry because Vauxhall then said, people working for Vauxhall, “If Ford are getting it, we must get it too or there will be a strike there.” Callaghan says, in his memoirs, he realised, at that point, the Election was lost. But much worse was to follow…

The Government’s policy was that if this sort of thing happened, there would be sanctions not on the union but on the firm, and the firm would not be given any Government contracts and they would not be given any export credit guarantees, and that needed a vote in Parliament. But the trouble was, the left-wing of the Labour Party was opposed to the 5% and they abstained on the vote. They included John Prescott at that time. They abstained on the vote and they joined together with the other parties opposed to it, primarily the Conservatives of course, to defeat the Government on the question of sanctions for Ford. And, perhaps wrongly, Callaghan refused to make it an issue of confidence. David Owen, the Foreign Secretary, said it was that moment he realised Labour had lost the next election.

There was then a strike in British Oxygen, where, again, the management were defeated, and this showed that the Government could not implement its policy in the private sector, and so there was to be a pay policy only in the public sector. So, you were to have free collective bargaining in the private sector, but a 5% incomes policy in the public sector, and that was not going to work because it was natural that those in the public sector would seek comparability. It was becoming clear 5% could not hold.

The next strike was very clever. It was by BBC technicians. Now, the BBC had just purchased “The Sound of Music” to show over Christmas to compete with ITV, which was at that time getting ahead of them in the ratings, and the technicians threatened to strike over Christmas. They had the support of the Board of Governors, who said there was a great pay disparity with ITV, which was in the private sector, and there was a problem with comparability. Now, the Government feared that the worst thing would be if there was a strike of the TV technicians over Christmas and people could not see “The Sound of Music” and then would all watch ITV, if there were no BBC programmes over Christmas. So, there was a settlement, which the Government did not resist, at 15%, and that let everything loose, as it were.

There were then walk-out strikes and militant picketing on the part of large numbers of workers – oil tanker drivers, lorry drivers, ambulance drivers, water and sewage workers, local government manual workers – and they put forward claims of between 20% and 40%. The culmination was a Day of Action, so-called, in January, at which 1.5 million public sector workers were on strike. All this coincided, as luck would have it, with a terrible winter – snow and cold and so on.

At this time, James Callaghan, through some misfortune really, he was at a summit conference dealing with strategic arms limitation in the sunny clime of Guadeloupe in the West Indies, and there photographs of him in the press, sunning himself, while everybody else was shivering in the cold with strikes, and many of the right-wing papers emphasised that by publishing pictures of very attractive young women in swimsuits also sunning themselves near James Callaghan. He came back from the summit to a temperature in Britain of -7 degrees, and very unwisely gave the following press conference…

[Recording plays]

JC: “Not at the moment, no. We have been on the brink of it I think, once or twice, during the last week, but we have stepped back from it. There is no point in declaring a state of emergency. We have had, I think, six states of emergency in the last few years. A state of emergency means that the Government intends to keep the essential life of the community going, and of course that is our first responsibility, and we shall do so. As you may know, plans for that are always ready. Those contingency plans, when we could see troubles looming ahead, were made before Christmas so that there was nothing - except of course putting touches to them, and you have always got to add to your preparations – there was nothing new or exciting that we had to do in that field.”

Interviewer/Journalist: “Can we have your reaction to the criticism that you should not have been away from the country during these past four or five days?”

JC: “I am sure everybody would have liked to have been with me, but I do not think anybody, except a few journalists, are very jealous of it. I think that they feel that we have been working hard, as indeed we have, and do you know, I actually swam, and I know that is the most exciting of the visit. But no, I think you should put all that kind of criticism in perspective, and one must not allow jealousy to dissuade you from doing what you know is the best thing.”

Interviewer/Journalist: “What is your general approach and view of the mounting chaos in the country at the moment?”

JC: “Well, that is a judgement that you are making. I promise you that if you look at it from outside, and perhaps you are taking a rather parochial view at the moment, I do not think that other people in the world would share the view that there is mounting chaos. You know, we have had strikes before. We have come close to the brink before. There is need for a great deal of industrial self-discipline in this country. I hope we shall gradually learn it and that we shall avoid hurting each other. But please do not run down your country by talking about mounting chaos.”

Interviewer/Journalist: “Does the Government’s pay policy stand firm, Prime Minister?”

JC: I do not think I want to discuss pay policy just at this moment, but you can take it that I have not wavered one iota from my views about what is the best way for this country to proceed in order to keep employment up and in order to make sure that inflation does not rise, and whatever happens on the industrial front cannot change that view – that stands, and we shall have to continue to follow it up. Now, do you not think that is sufficient after an eleven or nine hour flight overnight?”

Interviewer/Journalist: Thank you very much, Prime Minister.

JC: And no breakfast! However, with the mounting chaos that he talks about in the country, I doubt if I shall even find a cup of coffee, do you?!”

The headline in the Sun the next day was “Crisis, What Crisis?” Now, they were words that James Callaghan did not use, but he was very incautious I think to give that press conference at the airport before he had had time to grasp the mood of the country. It showed him very out of touch I think with what was happening.

The winter gradually became known as the Winter of Discontent. Now, that phrase was first coined by one of James Callaghan’s advisors, and it was coined, oddly enough, to cheer him up because he said it was like “Richard III”, if you know the beginning of “Richard III”, “Now is the Winter of Discontent, made glorious summer by this son of York,” that the Winter of Discontent would be followed by a glorious summer, but there was not going to be a glorious summer for the Labour Party or for James Callaghan, and of course the Conservatives were able to argue that the return of the Government would mean another Winter of Discontent.

The Winter of Discontent was not only the responsibility of the trade union leaders but the rank and file, who were rebelling against their leaders’ past acquiescence in incomes policy by which real wages had fallen. The TUC tried, rather feebly, to restrain the rank and file, but was unsuccessful.

There were huge strikes, with colossal effects on many vulnerable people. Bill Rodgers, the Transport Minister, was particularly upset by a strike of transport workers, which meant there were no supplies of chemotherapy chemicals for cancer victims, of which his mother was one.

The dustbins were not emptied, and you could see, in Leicester Square, huge piles of rubbish piling up and rats all about.

There was a strike in some parts of Manchester without water and people had to draw water from standpipes.

There was a strike of local authority gravediggers in Liverpool and Tameside, an unofficial strike admittedly, but it meant that there was some talk that people could not be buried – they might have to be buried at sea.

After it ended, on the 22nd of April, there was a letter from normally a Labour voter to the Guardian saying that, at the school her children were at, there was no heating, and the school had to be closed for a time, that in some parts of Manchester, there had been no water and people had to boil unpurified water before use, and that lorry drivers were trying to limit food supply, and she said, “I do not think much of their socialism.”

Callaghan was particularly affected by a strike of hospital porters at the Great Ormond Street Children’s Hospital, of which his wife was a governor, and when Tony Benn, in Cabinet, defended the strikes, he said, “What do you say about the thuggish act of a walkout without notice from a children’s hospital?!”

As you can imagine, the Conservatives made a tremendous amount of this, and I thought you might like to see a Conservative Election Broadcast, which does stretch things a bit but not wholly.

[Recording plays]

Narrator:

“Crisis, what crisis?!”

[Visual]

“Crisis, what crisis?!”

[Visual]

“Crisis, what crisis?!”

[Visual]

“Crisis, what crisis?!”

[Visual]

“Crisis, what crisis?!”

[Visual]

“Crisis, what crisis?!”

[Visual]

“Crisis, what crisis?!”

[Visual]

“Did you or did you not want better schooling for your children?”

“Guilty.”

“Now, did you or did you not want to buy your own home?”

“Guilty.”

“Did you or did you not make a profit last year?”

“Guilty. We’ll try not to do it again though.”

“Right. You’re sentenced to nationalisation – that should make an end to it.

I put it to you that you, a pensioner, expected to pay less tax on your savings just because you’ve spent 45 years working for them.”

“Guilty.”

“Is it not true that simply because you spent a few years training for a skilled job, you expected to earn more?”

“Guilty.”

“Is it not a fact that you failed to buy your weekend joint yet again because you claim they’re too expensive?”

“Guilty.”

“But I understand that you and your family had a holiday this year…”!

“The Labour philosophy taxes ambition…”

“Guilty.”

“…enthusiasm…”

“Guilty.”

“…achievement…”

“Guilty.”

“…the very things that create wealth, the things that made Britain great. We all know, in the last five years, the living standards of people in this country just have not grown the way they could. The Labour Government’s explanation for this is that Britain has been suffering because the whole world has been suffering. Well, the fact is that the world did have a bit of a cold, but it seems to be getting over the worst of it. In Britain, that cold seems to have turned into double-pneumonia. Look at France… Between 1974 and 1978, the average French worker saw his wages in terms of what they would buy go up by 60%; in Germany, the average worker saw his real wages go up by over 92%; the average Italian worker saw his real wages go up by over 47%. Meanwhile, in Britain, the average industrial worker has seen his real wages in terms of what they will buy only go up by 16%. And it is not just the French, Germans and Italians who have done better, the British worker has also done worse than, for example, workers in Denmark, Belgium, Canada, Ireland… It is not that they do not care about the unemployed, they do; and it is not that they do not mean well for our Health Service or our old people, of course they do. The Labour Party has always expressed the best intentions in these areas, but it is no good having good intentions if you cannot afford to carry them out. You cannot pay for better social services with good intentions. Caring that works costs cash. It all seems to come down to one thing: money, and the policies which create it. Labour never seem to have enough. Strange, you might think, when we are paying more tax under this present Labour Government than ever before, but despite all this tax they are collecting, they still have not got enough to pay for the proper standards of social services, and they never can get enough coming in from tax when people are not earning enough in the first place. So, the Labour Government has to take more and more of what we do earn to try and pay for the schools, hospitals and social services we all went.”

Margaret Thatcher:

“We have always had a sense of humour, and heaven knows we have needed it lately, but we have other characteristics too: a gift for invention, for initiative, and for hard work. Under Labour, these talents are going to waste because the Government takes too much away in tax. How often do you hear people say “Look how much they have taken from my pay-packet”? So, naturally, they ask for bigger pay rises to make up the difference, and it is not long before that pushes up prices – ask any housewife, she will tell you! This Government has increased prices more and faster than any other Government since records were kept. The only way to keep prices down is to get production up, and you do not do that by weighing people down with taxes and other restrictions. They do not work for the Chancellor of the Exchequer, they work for their families, so we have got to cut the tax on earnings and the tax on skill, give our people incentives, and once again Britain will be back in the race.”

Narrator:

“Do not just hope for a better life – vote for one!”

Well, you can see that, from the beginning of that Party Political Broadcast, that again the abyss seemed to be opening up. In January, there were suggestions that Callaghan himself broadcast to the nation, but he told his Press Officer, “How do you announce that the Government’s pay policy has completely collapsed?” Gerald Barnett, his Chief Secretary of the Treasury, said that if the Party kept its head, it could still win the Election, and Callaghan replied, “I am afraid we might!”

[Laughter]

He later said, sadly, to his Private Secretary, “I let the country down,” and this destroyed the Labour/trade union relationship to which he had devoted his life.

It had devastating effects not just in 1979 but it lasted even until 1992 when Labour unexpectedly lost the Election to John Major’s Conservatives. There were still memories of the Winter of Discontent and people were still fearful that if you voted Labour, the trade unions would come again to dominate. Even today, Conservatives say that a vote for Labour would mean a return to the 1970s.

Now, as if that was not bad enough, just as things seemed to be recovering, at the end of February, the devolution referendums were held, and they were a disaster. In Wales, devolution was defeated by four to one; in Scotland, it was carried narrowly by 33% to 31%, but Parliament had insisted on a 40% threshold, and Labour MPs, who had been sceptical of devolution anyway, were unwilling to support implementation, and that meant that the Nationalists withdrew their support from the Governments. The Conservatives, seeing their chance, put down a vote of confidence, and the Labour Party had to make all the effort it could to try and persuade the minority parties to support it.

The SNP said they would not support the Government under any circumstances, and Callaghan said, quite rightly, that they were “turkeys voting for Christmas” because their 11 MPs were reduced to two, and this, I think, even this has a resonance today because I think, in similar circumstances, the SNP would not defeat a Labour Government because they would not want to be held accountable in Scotland for letting the Conservatives into power in Westminster, so I think that, the memory of that, will prevent the SNP doing it again.

Plaid Cymru said they would support the Government - they were to the left of the SNP – and the Northern Irish Unionists said they would support the Government.

There was an attempt to win over the Liberals, which failed, but there were various shenanigans which, in retrospect, and perhaps even at the time, did not look very happy. Callaghan’s Principal Private Secretary said that there was an attempt to win over Cyril Smith, a Liberal MP at the time, with a peerage, but that did not work either because apparently Mrs Smith did not want her son to become Lord Cyril for some reason.

The last hope was from Northern Ireland because there was an independent Republican, who was a publican, in Fermanagh and Tyrone, called Frank Maguire, who very rarely came to the House of Commons, but there was hope that he would come, and the Labour whips cajoled him and begged him and so on, and he did come, but he came to abstain in person.

[Laughter]

In the vote of confidence, it was not clear what was going to happen, and Michael Foot made a brilliant speech, in which he particularly condemned the Liberals, and he referred to David Steel as someone who had turned from “the Boy David to being an elder statesman, with no intervening period”. But that was not sufficient, and the Government was defeated by one, so the Government had to go to the country. It hoped to last a bit longer – it could last until October ’79, and it hoped by then perhaps memories of the Winter of Discontent would have faded, but I think Callaghan had probably become a fatalist by then. This was the first Government defeated on a vote of confidence since MacDonald’s minority government in 1924.

When the defeat was announced, a group of left-wing MPs, led by Neil Kinnock, sang “The Red Flag” to keep their spirits up, but Callaghan, like Edward Heath, had been pushed into an election on a date that he did not really want – he would not have chosen that particular date, and clearly, the Conservatives were favourites to win the Election. They were 20% ahead in the polls in February, and 13% ahead in March.

Margaret Thatcher, in her first broadcast on the Election, struck a note which I think resonated with people. She said: “We have just had a devastating winter of industrial strikes, perhaps the worst in living memory, certainly the worst in mine. We saw the sick refused admission to hospital. We saw people unable to bury their dead. We saw children virtually locked out of their schools. We saw the country virtually at the mercy of secondary pickets and strike committees, and we saw a Government apparently helpless to do anything about it. I think we all know in our hearts it is time for a change.”

Now, during the campaign, Callaghan seemed much more experienced than Margaret Thatcher, and he concentrated on the issue of prices. He said the great danger of a Conservative Government would be that prices would rise very rapidly because they proposed to increase VAT in particular. One of Callaghan’s advisors said, “You know, you just might win the Election, things might be going in your favour,” and Callaghan said no. He said, “There are times, perhaps once every 30 years, when there is a sea-change in politics. It then does not matter what you say or do, there is shift in what the public wants and what it approves of. I suspect there is now such a sea-change and it is for Mrs Thatcher.” And it proved to be so….

As I say, there was a swing of just over 5%, which was the largest since the War. The Labour percentage of the vote was the lowest since 1931, and the Conservatives gained 61 seats from Labour. The swing was greatest in the South and the Midlands, and greatest amongst skilled workers, and it confirmed an aphorism of Aneurin Bevan that “The worker votes at the polls against the indiscipline he has shown before,” that people voted, the same people perhaps who had been on strike, or supported strikes, were now voting Conservative. There was a much lower swing in the North and in Scotland, and indeed there was a slight swing to Labour, a hint of the future, in Glasgow and Edinburgh, a swing of about 1.5% to Labour. So, the South and the North were becoming separate, and Scotland becoming even more, so even less likely to support the Conservatives.

This came at the end of a decade of the 1970s which had been characterised by upheavals. You had had one hung parliament, one narrow majority which led to a hung parliament, three changes of government, and the seeming undermining of the two-party system by the Liberals and the Nationalists, and to the surprise of many, the General Election inaugurated a period of stability and a seeming restoration of the two-party system.

But it left one crucial question open, the question raised by Edward Heath in 1974: can any Government govern against the wishes of the trade unions? And that was not such a new question as you might imagine. Even in the Attlee Government, that question had been there. The Home Secretary under the Attlee Government, a man called Chuter Ede, in 1948, when there was a dock strike, he said to the leader of the Transport & General Workers Union, “I sometimes wonder, Mr Deakin, who governs this country, the Government or the Transport & General Workers Union,” and Mr Deakin replied, “That is a question I would prefer to leave you to answer, Home Secretary.” That question was answered by Margaret Thatcher.

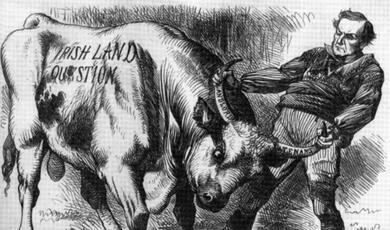

In 1979, the Daily Telegraph published a cartoon called “Secondary Voting”, a play on secondary picketing, and at the bottom of the cartoon – the cartoon itself showed James Callaghan with some very sinister-looking trade unionists behind him, and the caption below was “Vote Labour – Or Else!”

Margaret Thatcher did answer that question very firmly, and one of Callaghan’s advisors said that the public sector unions put Margaret Thatcher into power and she “…proceeded to thank them in her own individual way”.

Now, this is eighteen years of Conservative rule beginning and it was a watershed election, I think. In her final broadcast before the 1979 Election, Margaret Thatcher emphasised not continuity with the past, which was the usual Conservative theme, but the need to make a clean break. There was, she said, “…a worldwide revolt against big government, excessive taxation and bureaucracy – an era is drawing to close.” So, it was not just the end of a Government, it was the end of an era.

Britain, after the War, it may be argued, had failed to reconstruct the country as had been done in the defeated countries, Germany and Japan, and in an occupied country, France. Governments of both left and right had accepted the growing Wartime role of the State and sought to improve and extend it, with an emphasis on conciliated organised labour and extending the privileges of the better-off to all. Problems relating to the production of wealth and international competition had been neglected – they did not matter in Wartime, and they were neglected in peacetime. Governments of both left and right were insufficiently sensitive, it may be argued, to the dangers of a large public sector and over-powerful trade unions, and the Election of 1979 brought the contradictions of the post-War settlement to a head, and that is why it heralded a new regime. It is possible that the economic crash of 2008 marks the end of the era that began in 1979, but on that, the jury is still out and we do not know – that is what Ed Miliband thinks, and his judgement will be tested in this year’s General Election. But what I think cannot be doubted is that the General Election of 1979 did mark the end of one era and the beginning of another, and that we are still living with the consequences of that Election.

Thank you very much.

© Professor Vernon Bogdanor, 2015

Part of:

This event was on Tue, 10 Mar 2015

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login