The Beginnings of Protestantism in Asia

Share

- Details

- Text

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

Early Protestant empires in Asia – in Indonesia, Sri Lanka, India, Taiwan and elsewhere – brought missionaries with them. Like their Catholic predecessors, they learned that winning converts was formidably difficult, especially in empires that were principally commercial.

As this lecture will show, some concluded that the effort was futile; others grew increasingly coercive; but others still began to explore ways of learning from and with indigenous peoples. The results, for good or ill, set patterns that still affect the region today.

Download Text

The Beginning of Protestantism in Asia

Professor Alec Ryrie

27th April 2022

In 1712 George Lewis was a Welsh chaplain working for the British East India Company in the port of Chennai, then known as Madras, on India’s south-western coast. The job for which the Company had hired him, and a handful of other Anglican chaplains was simply to provide religious services for the Company’s expatriates, and, perhaps, also their illegitimate children. It was a perfectly decent living for a clergyman, with definite opportunities to make some money on the side through trading in your own right, but as spiritual vocations go, it was unambitious, and every so often these men’s consciences had a way of stirring. In fact, in October 1712 Lewis was in a state of some excitement. 250km south of Madras was a rather more modest imperial foothold: the Danish East India Company’s settlement in the town of Tranquebar, now called Tharangambadi. Over the previous six years two young Protestant ministers had been working there, not with the small number of Danish expats but with the Tamil population, whom they hoped to convert to their brand of Christianity. Lewis was impressed. He wrote to the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge, the SPCK, a fledgling outfit in London that had taken an interest in the Danish mission: we’ll be hearing more about the SPCK. He said: ‘The Missionary’s at Tranquebar ought and must be encouraged. It is the first attempt the Protestants have ever made in that kind. [And, using a Biblical image for nurturing and encouraging something fragile and tentative, he continued:] We must not put out the Smoaking Flax. It would give our adversary’s the Papists, who boast so much of their Congregation de Propaganda Fide, too much cause to triumph over us.’

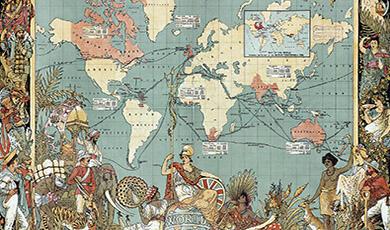

We will come back to south-western India later on, but for now I want you to notice two things about this comment. First, the fact that Lewis immediately frames a missionary effort amongst an overwhelmingly Hindu population as a spiritual struggle, not with Hinduism, but with Catholicism. And second, his claim that this is the ‘first attempt the Protestants have ever made in that kind’. As we’ll see, that’s not exactly true. But it’s also not all that surprising he would have thought this. And it is certainly true that the beginnings of Protestant Christianity in Asia, our subject today, is a slow and uncertain story, and one which is quite distinct from those we’ve told so far. The missionary contexts we’ve looked at so far in these lectures, amongst Native Americans and enslaved Africans, have been defined by imperial power: these happened in contexts of conquest, of expansionist settlement, of enslavement. In Asia the situation during our period, up to the late eighteenth century, was very different. There was certainly a European imperial presence in parts of Asia. There were even a few territories, mostly islands or small coastal enclaves, that had been brought under partial or complete military control by European powers, though that control was always fragile. But there was as yet no real attempt at large-scale conquest, and no attempt at all to create settler colonies of the kind found in the Americas and in southern Africa. These were not, or not yet, territorial empires. The Portuguese, the first Europeans to establish a presence in the Indian Ocean and in East Asia, established a series of footholds in the sixteenth century: Hormuz at the mouth of the Persian Gulf, Goa in eastern India, Malacca in modern Malaysia, Macau on the south coast of China. In each case they fortified, used military force, held territory, but only as much as they needed to establish secure trading posts. The reason that enormously powerful states like Safavid Persia, the Mughal Empire in India and Ming China were willing to allow this kind of thing was that the Portuguese were not interested in territorial conquest, but in maritime trade, a grubbily commercial enterprise which the great Asian states generally saw as beneath their dignity and were perfectly happy to outsource to these peculiar Europeans with their agile and heavily armed little ships. So, the main rivals for Portuguese dominance of the lucrative intra-Asian trade were, oddly enough, not the great Asian powers at all, but other Europeans. And it is a sign of how commercial all this was that those European rivals all chose to pursue their Asian ambitions, not through direct conquest or settlement in the old-fashioned way, but through the establishment of trading companies. We’ve already met the British East India Company, the oldest of these rivals to Portugal, established in 1600 – it was English, not British, at that point; and we’ve met the Danish company too, a comparative tiddler; but the most powerful and important for our whole period was the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the Dutch East India Company, established in 1602. We might think we live in an age when multinational corporations can be more powerful than states, but these are companies that make Amazon or Exxon Mobil look lily-livered and squeamish. A better modern analogy might be the Russian energy company Gazprom, a publicly traded company which is majority owned by the Russian state and is plainly both a highly lucrative commercial enterprise and also an instrument of Russian foreign policy. The Protestant maritime powers in northern Europe in the years around 1600 were locked in a desperate struggle for survival with the joint monarchy of Spain and Portugal. This empire of Antichrist, as the Protestants saw it, tried repeatedly to invade England, the great Armada of 1588 being only the best-known attempt, and was until the 1640s actively attempting to reconquer the Dutch Republic, which had thrown off Spanish rule in the 1570s. And the Protestants knew that the financial lifeblood of Spanish and Portuguese power was their global empires, the gold and silver of the Americas and the staggeringly lucrative trade in spices and other goods from Asia. Disrupting that trade as best they could, and seizing some of it for themselves, was a military necessity. So, these companies, which were set up to be self-financing and self-governing, and which kept the governments and the publics of their home countries at arm’s length, were also never just companies. They were weapons of war. In 1603, the year after the foundation of the Dutch East India Company, its naval commander in the East, Jacob van Heemskerck wrote a triumphant report to the Company’s directors, outlining his early victories, and commented: ‘May God’s glory be exalted among so many different nations, peoples and countries by means of the true protestant religion. Perhaps the Lord will use a small, despised country and nation [meaning the Netherlands, of course] to work his mighty miracles.’ Was the money-making a means of defeating the forces of Antichrist, or was throttling the Portuguese empire a means of making money? Happily, that was not a question they needed to answer. Though it will not surprise you to learn that money-making has a momentum of its own, and that entities which were created as mercantile means to political ends slowly became more nakedly commercial.

Alongside this commercial rivalry between the Catholic and the Protestant powers – or perhaps, one of the arenas in which that rivalry was fought – was a missionary rivalry. The Portuguese used their commercial empire as a vector for Catholic missions. Goa in particular became a hub, with priests quickly fanning out across India. This was with the permission and support of Portugal and the other Catholic powers, but behind it all stood the papacy, whose own missionary headquarters, the Congregatio de Propaganda Fide which George Lewis mentioned, was founded in 1622: there is a back-handed compliment to its effectiveness in the meaning Protestants then gave to the word propaganda. Because the reality was that, while in commercial terms the Protestants might be making inroads, in religious terms they were a long way behind. The first Protestants that we know of in Asia were in fact soldiers and mariners recruited to work for the Portuguese. In 1552 a group of so-called Lutherans were detected by Portuguese inquisitors on Hormuz, and in the same year a Portuguese Jesuit in India described meeting Protestant English, Dutch and German soldiers in Portuguese service. In the first half-century after a formal Inquisition tribunal was established in Goa in 1560, they tried around fifty cases of suspected Protestantism – although this was a tiny sliver of their overall business, which was chiefly trying to police the orthodoxy of their new Indian converts.

Protestants back in their European heartlands were well aware that a march was being stolen on them. When the Dutch East India Company’s charter was renewed in 1622, it included an explicit statement that one of the Company’s purposes was ‘the preservation of the public Reformed faith’. And indeed, the Dutch company in particular did see a missionary dimension to its work, but always within limits. In the spice islands of Indonesia, when the Dutch established settlements on islands under Muslim rule, they readily adopted treaties in which attempts to win converts, either from Islam to Christianity or vice versa, were strictly forbidden, and when Dutch preachers complained they were ignored or silenced. The plainest or most notorious case is Japan, where the association between Christianity and foreign-backed subversion had become so strong by the 1620s that Christianity was outlawed and brutally suppressed, and the whole Japanese empire was closed to foreigners of any kind. The only traders who managed to negotiate a partial exception to this rule were the Dutch, who in the 1630s were permitted to establish a trading depot on the island of Hirado, off the coast of Nagasaki. One of the conditions was that there be absolutely no hint of Christianity to their presence. Dutch churchmen protested vigorously about this, to no avail. Dutch ships were required to seal their Bibles in caskets for as long as they were in Japanese waters. When the Dutch built a warehouse on the island and inscribed it with the date according to the Christian calendar, Anno Domini 1640, they were ordered to demolish the entire warehouse. A Swedish Lutheran soldier in Dutch service who visited Japan on a trade mission in 1651-2 recorded that:

When the Ships arrive, Placards are nailed to the great Mast by diem [and this was by Dutch officials, not by the Japanese themselves], wherein all Gestures indicating Christianity are openly forbidden, not to mention the Name of Christ on Pain of Death, [or to] read Prayers before sitting down at or when leaving the Table, in the Evening or in the Morning. Truly, in my Time, when I was there in their Service, we were forbidden to change any of our Clothes on Sunday, so that we would not by this means appear to be Christians.

Willman was well aware of the bloody persecution of Christians in Japan, which he found horrific, even though the victims were Catholics. And his conscience was clearly troubled by these orders. But, he said, ‘the Dutch for the Sake of Money and Profit can well stand and abide’ by whatever rules they were given.

But this was not the whole story. The main reason the Company’s charter was revised in 1622 was that it had begun doing more than just trading: it had started actually acquiring territory. The island of Ambon in modern Indonesia, roughly halfway between Sulawesi and New Guinea, was the first territory that Dutch East India Company actually claimed, having expelled the Portuguese. Ambon was at that time the world’s main producer of cloves: the Dutch, indeed, aspired to a monopoly of clove production, and in 1625 conducted a raid into the one part of the island they did not control, burning some 65,000 trees in an attempt to wipe out any competition. They also, in an early sign that this was not simply about economic war with the Catholic powers, summarily executed ten English sailors, an incident that poisoned diplomatic relations between England and the Netherlands for decades. – Anyway, the Portuguese had governed the island for the best part of a century, and that included hosting a Catholic missionary effort. This took the conventional shape. You will read accounts of Catholic missionaries of this era carrying out mass baptisms almost indiscriminately, with no attempt to ensure that the subjects understood what was happening, and this is an exaggeration – but it’s not completely baseless. Catholic missionaries were usually prepared to baptise anyone who was willing publicly to associate themselves with the God of the Portuguese and to recite certain formulae. After all, baptism is a profound spiritual mystery which no mortal fully understands, so how can you justify excluding people from the saving grace of the sacrament by sitting in judgement over their understanding? Catholics, unlike Protestants, believed and believe that baptism is an effective means of grace, not just an outward sign, but a true spiritual washing that changes the status of a soul before God. You should not be miserly in giving such a gift. So, when the Dutch took Ambon in 1605, they inherited a population of some 16,000 self-identified Catholic Christians. This awkward responsibility was not at all one for which they were prepared.

The Company’s instinct was to try to reproduce the religious settlement of the Dutch Republic in the Spice Islands. That meant a monopoly on public worship for the Reformed church, and toleration for private practice of other religions. The Dutch admiral who had captured Ambon, who was of course a long way from being any kind of clergyman and was making this stuff up as he went along, signed a treaty with the indigenous people stating that ‘everyone may live in that belief that God puts in his heart, or he believes to be holy; but no-one may molest another, or cause him trouble’. Even some of the Portuguese were allowed to stay, on the basis that they were married to indigenous women. But public monuments of Catholicism had to go: crucifixes and images of saints were blasphemous idolatries as far as the Dutch were concerned. Three of the four churches on the island were closed. The fourth was in theory taken over for Protestant worship, but the Dutch fleet had not come prepared for that. It was ten years before even a single Protestant minister could be found for the island; until then they had to make do with an untrained lay person who had been licenced to read services on board ship, and with some prayers read by the Company physician. Meanwhile the Dutch were aggressively asserting their control over the island, which included a forcible monopoly on spice trading and using forced labour. And the everyday behaviour of the Dutch traders and soldiers – an exclusively male community, of course – was, let’s say, not calculated to burnish Protestantism’s reputation for high moral standards. By contrast, Islam was gaining a foothold on the island as it spread east through the Indonesian archipelago; and the Dutch pushed back. There were incidents of mosque-burning, of Muslims being forced to eat pork, of Christian converts to Islam being imprisoned. In the late 1610s there was a major rebellion against Dutch rule, which was put down with some ferocity. Things were not going well.

A Protestant minister finally arrived in 1615, but it was not a success. He tried to set up a school, and did learn some Malay, the lingua franca of the region, but he made no secret of his disdain for the Ambonese, whom he called ‘dull-witted and lazy’. The real beginnings of a change came with his successor, Sebastiaen Danckaerts, a Protestant minister with some years of Far Eastern experience under his belt when he came to Ambon on 1618. This was his assessment of the situation after some two years on the island:

These people here call themselves Christians, but still seek secretly the devil, while they think that they affirm their confession by eating pork. Many of them indeed come to church on Sunday, but this is more a matter of compulsion than of conviction because they will be fined a quarter of a real if they do not come.

Perhaps one out of fifty of them, he guessed, even knew what their Christian name was, the name given to them when they were baptised. He redoubled the effort to provide services in Malay, and crucially, in 1619, he persuaded Company’s governor-general in the East to offer a handsome bribe of a pound of rice per day for every child who attended the school. This was not subtle, and it seems to be the origin of the term ‘rice-Christian’, which right through into the 20th century was what Protestant missionaries in Asia called people who affiliated with mission churches in the hope of receiving handouts or other material help. But it worked, after a fashion at least. The schools boomed. The schools began to expand, employing local men as teachers, using the Malay catechetical texts that Danckaerts and his predecessor had produced. In 1620 they began to move out into the countryside beyond Ambon town, taking hand-copied texts with them in the absence of any other books or equipment. By 1633, there were 32 schools on the island with 1200 pupils on their books. Fifty years later, that had grown to 46 schools and 3,200 pupils.

The Christianisation of the eastern Moluccas under Dutch rule was not pretty. Dutch control was enforced with some ferocity and several rebellions were subdued with exemplary brutality; in some cases, recalcitrant populations were simply deported, and notoriously, on the nutmeg-growing Banda islands, there were large-scale massacres. But the process ground on, especially once the Dutch realised, by mid-century, that they were in a footrace with the expanding Muslim presence in those islands and that affiliation to Protestantism was a way of cementing Company rule. On the larger neighbouring island of Seram, from the 1670s onwards, bribery was supplemented with open pressure: in one village in south Seram, in 1677, there was a mass baptism, with the Dutch governor present. The Company paid for two cows and four and a half tonnes of rice for the festivities, and the governor presented cloths to the converts ‘in order,’ it was said, ‘to arouse honest jealousy among the pagans living in the region’. Meanwhile, the death penalty was threatened for venerating traditional religious images. The result, after a generation or two, in much of the archipelago, was compliance to what the indigenous people sometimes called agama Kumpeni, the religion of the Company.

That makes it sound like mere sullen compliance, but that is not quite the whole story. In some parts of the Indonesian archipelago, such as northern Sulawesi, a real popular Protestantism was eventually built. A more typical example is the city of Batavia, the predecessor of the modern city of Jakarta, which (again) was seized from the Portuguese in 1619 and became the capital of the Dutch East India Company’s empire. A census from 1679 gives us an idea of how this was working. At that date the city’s total population was a little over 32,000. Of these, just over 2,000 were European expatriates: merchants, soldiers, Company officials, sometimes their families. Just over 16,000, so half of the population, were enslaved – and this group were very multi-ethnic, with Portuguese still dominant as the lingua franca. But the culture of slavery in this region was very different from that in the Caribbean and the Americas. These were mostly household slaves, for both Europeans and high-status Asians, and one of the accepted symbols of status in this society was ostentatious freeing of slaves after a period of service. So alongside the enslaved population was a substantial group, a sixth of the population, who were so-called mardijkers, freedpeople, that is, former slaves or their descendants, mostly speakers of Portuguese creole. And in Batavia, by this date, most of these people were Christians.

The majority of these Christians, perhaps two-thirds, were still Catholics, but there was a large and growing Protestant minority. The Dutch Reformed Church in Batavia claimed a total of 500 members in 1658, which might sound modest, but the Reformed Church had a very different view of membership from the Catholics: even back home in the Netherlands it was rare for more than 20% of the population to be full church members, as this was limited to adults who had formally testified to an appropriately sophisticated understanding of the faith and had submitted themselves to and had their morals approved by the church’s disciplinary structures. The majority of church members were women – in Batavia the figure was as high as 75%; women found that having an institution that could publicly vouch for their morals was particularly valuable. So we might presume that for every formal church member there were two or three more adherents of the Reformed church. But as mardijkers were drawn into the Reformed Church that number of members began to shoot up. By 1674 there were 2,300 church members in Batavia: by 1700, 5,000. What drove this surge was the creation of a new church office: the lay catechist. These men, all of whom were of Asian descent and most of whom were mardijkers themselves, were each given a district of the city to visit. By the mid-1660s there were eighteen of them; by 1706 there were thirty-four. They reported directly to the ordained ministers and, crucially, maintained the lists of church membership. It was a full-time job: going from house to house providing Christian instruction to church members and their families, almost all of them in Portuguese or Malay rather than Dutch. The most tangible sign of this growth was the erection of new church buildings: this one, built in 1682, no longer exists, but the Portuguese Buitenkerk, erected outside the town walls in 1693, is still there, the oldest extant church in Indonesia.

There is a similar story in another Dutch colony, the island we know as Sri Lanka and which they called Ceylon. Again, the Dutch inherited a mixed religious picture, with longstanding Buddhist and Hindu populations mixed with a substantial number who had converted to Catholicism under Portuguese rule. And again, the process of building a Protestant community was slow and painful. But it happened, to some extent at least. Schools were founded and attendance was required. Churches were built, many of them, like this one in Colombo, still standing and in use. During the eighteenth century, a printing press was established, producing books in Tamil and Sinhalese for use in the schools and the churches. In both cases you can see the imprint of the VOC, the Company, on the title page. Seminaries were founded, one in Jaffna and one in Colombo, which trained young men both for the colonial administration and also for the ministry: at least a dozen local men were fully ordained as ministers during the eighteenth century, some of them after further training in the Netherlands. When the British seized the island from the Dutch during the Napoleonic wars, they counted the Protestant population at 236,109, something like a fifth of the population of the island’s maritime provinces. And while the British thought that the Protestant church was scandalously understaffed, they reckoned the educational system was sound, and took it over wholesale. Ceylon / Sri Lanka, then, shows what the Protestant tortoise could do when given time to match itself against the Catholic hare. It couldn’t actually catch up – we all know that in real life tortoises don’t win races – but it could put on a perfectly respectable showing in a plodding, institutional way.

But for many Protestants, this grinding, limited church-building was deeply frustrating. This sort of thing was not how the apostles set the world on fire: luring or forcing children into schools, drilling freed slaves to memorise texts, and hoping that over the generations habit would harden into something like faith. Surely there was a better way? In the Dutch empire, there was a surge of optimism in the 1620s. Four chiefs’ sons from Ambon were sent to the Netherlands for education in 1621. In 1623, the year after the Congregatio de Propaganda Fide was founded in Rome, the Dutch minister Sebastiaen Danckaerts, whom we met as the founder of the schools’ programme on Ambon, was on a trip back home, and he persuaded the East India Company to open a Collegium Indicum, an Indian college, to train ministers for missionary work in the Far East. Perhaps a few highly skilled ministers and high-status indigenous converts could be the spark that would set all Asia alight. But ten years later, when the Ambonese youths were sent home – at least the three of them who had survived – the island’s Protestant minister was unimpressed. ‘It is lamentable that those people ... who have cost the Directors so much are not more thankful for what they have enjoyed, because they have completely forgotten their study and show no enthusiasm for the Christian religion.’ The following year the Collegium Indicum was closed down, having produced no more than twelve students: ‘college’ was a grand name for an institution which had only one dedicated professor and had met in his home. The East India Company declared it now had as many ministers as it could employ and there was no need for a further recruitment stream. I won’t say that the Collegium had no impact, because it does play a role in one other truly remarkable story from the Dutch empire, which we’ll come back to in the final lecture of this series. But an equivalent to Rome’s Propaganda Fide it was not.

For most of the seventeenth century, Protestants in Europe talked and dreamed of taking their Gospel to Asia in earnest but didn’t do very much about it. Books were published and sermons were preached, but the great trading companies knew how to run a tight ship and would not permit any freelance religious enthusiasts stirring up trouble: even the Dutch East India Company’s own ministers were liable to be unceremoniously shipped home if they clashed with the Company’s governors. Insofar as self-starting enthusiasts made any impact, it was closer to home, in the Ottoman Empire, the great Turkish-ruled empire that embraced most of the Middle East and North Africa as well as a swathe of south-eastern Europe. The most eye-catching efforts were undertaken by the Quakers, that radically egalitarian Protestant movement that sprang up in England in the years after the Civil War. The Quaker leader George Fox fired off a series of prophetic letters to the Turkish Sultan, the Emperor of China and so forth adjuring them to hearken to the light of Christ within them. A number of Quakers set out to deliver these messages in person: their mission, as one Quaker historian puts it, was ‘a service abundant in persecution but barren in fruit’. In 1661, for example, two more Quakers were inspired to travel to the Turks and ultimately on to China, and set out bearing a sheaf of these letters, including a catch-all one addressed ‘To all the nations under the whole heavens.’ They made it as far as Alexandria, where the horrified English consul reported that they ‘did throw pamphlets about the streets in Hebrew, Arabic and Latin’. The consul managed to get them released to his custody and had them shipped home: it could have been much worse. Another party were likewise intercepted by the English consul Smyrna, who wrote that ‘we sufficiently have had experience that the carriage of that sort of people is ridiculous and is capable to bring dishonour to our nation’.

Others made it a little further. One of the most remarkable stories, though thinly documented, is that of the German Lutheran preacher Peter Heyling. This isn’t about Asia as such, but I hope you agree it’s part of today’s story. Heyling set out for Egypt in 1633 – intending not to convert Muslims, which conventional wisdom held to be both impossible and impossibly dangerous, but to bring the Protestant gospel to the ancient Christian churches of the East. He learned Arabic and managed to befriend senior figures in both the Syrian Orthodox and the Coptic churches. Then an unexpected chance came his way. The kingdom of Abyssinia, or Ethiopia, had been Christian since ancient times: this map rather exaggerates its size, but it was considerable. Earlier in the century Roman Catholic missionaries had established themselves there, to try to bring the Ethiopian Orthodox church into communion with Rome. In 1634, however, a new Ethiopian emperor came to the throne who broke with the Catholics and renewed the ancient links with Coptic Egypt. Hearing of this, Heyling saw his chance and travelled to Ethiopia. Whether the emperor would have proceeded to expelled or executed all of the Catholic missionaries in 1638 without Heyling’s influence, we do not know. We do know that Heyling remained in Ethiopia for seventeen years, married the emperor’s daughter, won a reputation for studiousness and holiness, and translated the New Testament into Amharic. But as so often, in the end nothing came of it. Heyling was killed in 1656 after a quarrel with a Turkish governor in Sudan. The Lutheran minister who was sent to assist him, rather embarrassingly, himself converted to Catholicism en route.

The hope that the way to the Middle East might lie through the Eastern and Oriental Orthodox churches was a common one. Muslim rulers violently objected to any Christian missionary efforts, whereas Protestants thought they might have better prospects with the Eastern churches, who hated the Pope as much as they did. And they reasoned that if anyone stood any chance of converting Muslims, it would not be foreigners but a reinvigorated indigenous Christian church. If there was an institutional route to this, it was, once again, the chartered trading companies: the English Levant Company traded out of Aleppo in modern Syria, and a series of English Protestant chaplains there made cautious contacts with the Oriental Orthodox churches. For enthusiasts back home, the presence of the Aleppo chaplaincy was an opportunity, and the way to exploit that opportunity was to distribute books. Robert Boyle, the brilliant Irish Protestant chemist, was a missionary enthusiast, and was rich enough to bankroll a 1660 Arabic edition of the bestselling tract On the truth of the Christian religion, by the great Dutch philosopher Hugo Grotius. It was apparently dispersed by the English merchants in Aleppo. Boyle also funded a Turkish edition of the New Testament. An Arabic edition of the English Book of Common Prayer followed later in the century. None of these projects had any impact at all that we can trace. If Catholic missionaries believed that baptism had its own intrinsic, saving power and ought to be administered as liberally as possible, Protestant missionaries believed the same thing about books: like the Quakers in Alexandra flinging books into the street, they knew that God’s word was alive. If they merely scattered the seed abroad, they believed, it would take root.

In 1720, the SPCK – the English publishing and missionary society I mentioned at the start – was approached with a new scheme to print an Arabic New Testament and psalter, with the apparent backing of the Orthodox patriarch of Antioch. I say apparent because it quickly became clear that the patriarch had no real interest in the project, but merely wanted allies in local intrigues against Roman Catholic missionaries. Yet the SPCK seized on the idea, despite the lack of any plan for distributing the books beyond sending them in bulk to the English consul in Aleppo. The patriarch died in 1724, and his successor did not even pretend to be interested in cooking up schemes with English heretics, but by now the SPCK was hooked. They set out to raise an eye-watering £2,400 to print 8,000 copies, a sum which included the forging of a new set of Arabic type. Remarkably, they overshot the mark. By 1737 the SPCK had produced over 6,000 Arabic Psalters, 10,000 Arabic New Testaments and 5,000 Arabic catechisms, at a total cost of some £3,000, by far the single most expensive project the Society had ever undertaken. And almost no-one wanted them. Hundreds were indeed sent to Aleppo for distribution, where to the best of our knowledge they sank without trace. Others were sent to SPCK correspondents in Russia, Persia and India, where we may presume demand for Arabic-language Christian materials was weak. But half a century later, well over half of the New Testaments and catechisms were still sitting in the SPCK’s warehouses in London awaiting anyone who might be interested in them. Hundreds of copies from that same print run were being distributed by the British and Foreign Bible Society in 1822. Protestant books were, indeed, like Catholic baptisms: you could run up impressive numbers but that did not mean you were having the desired effect.

So, when George Lewis in Madras said about the Protestant missionaries in Tranquebar that ‘it is the first attempt the Protestants have ever made in that kind’, he was wrong, but you can see what he meant. Because it does have to be said that the Tranquebar mission was a little different from the other ventures of the time, and perhaps a sign of things to come. It’s a difficult subject to discuss because it’s been heavily mythologised – and in fact, as Lewis’ comments suggest, that mythologisation process is something that was happening in real time. But scrape away the layers and it is still clear something pretty unusual was going on.

Two things make this venture stand out: the vital combination of structures and people. The mission was based in the Danish East India Company’s territory, but it was not a Company project; indeed, the Company was to begin with actively hostile to it, and the lead missionary, Bartholomaeus Ziegenbalg, was actually imprisoned by the colony’s governor for a few months in 1708-9 after he tried to intervene in a debt dispute between a Tamil widow and an employee of the Company. The experience was uncomfortable but hugely bolstered his credibility with the Tamil population. The mission was initially sponsored by King Frederick IV of Denmark, a convert to the evangelical Lutheran movement known as Pietism, whose hallmark was bypassing existing church and state structures and taking its preaching direct to the common people. This was the first opportunity for Pietism to reach beyond Europe, and so King Frederick’s idea attracted the attention of the University of Halle in Prussia, the engine-room of Pietism, and of the formidable religious entrepreneur August Hermann Francke, professor of theology at Halle who sat at the centre of the Pietist network. King Frederick provided the official permission to work in the colony, overruling the Company’s objections. Halle provided the personnel: all of the missionaries who worked in this Danish-sponsored mission throughout the century were in fact German. But pretty soon a third element entered the equation: the English SPCK took an interest. Their instinct, of course, was to throw books at the problem, and they in fact paid to have a printing press and specially made type shipped out to Tranquebar, despite the very considerable logistical difficulties of doing this: this was in the middle of a war with France, the ship was attacked, the press ended up in Brazil, it had to be ransomed, but it did eventually arrive and the missionaries were able to make good use of it, producing this Tamil New Testament in 1715, though we might question whether this was the best use of funds. But the SPCK also became the main financial underwriters of the mission, paying for almost everything apart from the actual salaries of the missionaries, and, crucially, persuading the British East India Company to provide free passage for missionaries and their supplies. This unique three-cornered Danish-German-English arrangement in fact worked remarkably well. All three parties brought something different to the table – official backing, a steady supply of personnel and a steady supply of cash – and all three were able to commit to doing so over a period of decades. There were occasional prickles in the relationship – Anglicans and Lutherans were not very different, but there were certain well-known disagreements, and the missionaries themselves were acutely aware of the need to steer clear of any delicate liturgical or jurisdictional issues. But this may in fact have been the mission’s strongest point: although sponsored by three institutions representing state churches, the balance meant that it was never under the sway of a single state, much less a trading company. For a sign of the difference, look what became of George Lewis’ enthusiasm for the British East India Company to emulate the Tranquebar mission. His successor at Madras tried to follow the Tranquebar example by founding a charity school. The Company did not exactly try to stop it, but they did direct the project in a particular direction: the school that eventually opened at Madras in 1716 was an English-language school teaching the mixed-race children of irregular liaisons between Company staff and soldiers and Tamil women. Now plainly making some provision for these unfortunate people was worthwhile, and the missionaries at Tranquebar had by then also set up a small school offering instruction in Danish for the same clientele – but this was alongside four rather larger institutions offering tuition in Tamil or, in one case, Portuguese. Their focus was always and primarily on the indigenous population.

Alongside its unique institutional basis, the mission’s other gift was its people. There is no getting around the fact that Bartholomaeus Ziegenbalg was an exceptional figure. Reading his correspondence is positively exhausting. He quickly decided that it was essential that he and the others master the Tamil language, devoted himself almost full-time to language study for his first year, and by the end of that year had written his first sermon in Tamil. He compiled dictionaries and made it his business to master the Tamil literary tradition, employing poets to teach him, and collecting and copying huge numbers of the palm-leaf books used in the region: he had acquired over 600 of them in his first eight years. What really makes this remarkable is his openness to Tamil culture. He wrote several detailed ethnographic accounts of Tamil culture and belief, including a whole book on south Indian religion which he wanted Francke and the University of Halle to publish: Francke refused, arguing that the missionaries had been sent to stamp out heathenism, not to publicise it, but Ziegenbalg had by then come to a rather more subtle view of the matter. He quickly moved on from his initial descriptions of ‘their ridiculous Theology’ as ‘useless Trash’ – to be fair, he used the same term for Aristotelian philosophy. Instead, he discovered that in Tamil writings, ‘one might discover things very fit to entertain the Curiosity of many a learned Head in Europe’, and he called them ‘a witty and sagacious People’, who ‘lead a very quiet, honest and virtuous Life, by the mere Influence of their natural Abilities’. The principal obstacle to winning them over to Christianity, he quickly concluded, was the egregious moral example of actual Christians in India, and he set about ensuring that he and the other missionaries, at least, offered a different model. The mood of his correspondence is frustration with how slowly things were progressing, but when you step back it is profoundly impressive: a stone church built within the first year (this is the replacement built in 1718, and still standing and in use). Crowds too big for the building attending the twice-weekly sermons. Five free schools with a combined registration of around a hundred, equally split between girls and boys, within the first five years. Actual baptisms were slower, because in typical Protestant fashion, Ziegenbalg was punctilious about catechising and examining baptismal candidates and only admitted those of whose faith he was confident: but by the time of his death in 1719, he had baptised some 250 people. That does not of course include Indian converts from Catholicism, who made up a substantial part of his congregation.

One missionary winning 250 converts from a standing start is in some ways impressive; it is also trivial. And while some of Ziegenbalg’s successors in the Danish-Halle-SPCK mission in the rest of the century – we’ll meet one of them in particular in the next lecture – were able to build on his achievements, it’s also clear that those achievements were limited. What makes the Tranquebar mission stand out in our story, however, is that it had found a way of combining structures and people to build a community over the long term, with the foundations Ziegenbalg and his colleagues lay underpinning what happened over the following decades. Admittedly, that intricate tripartite structure also made it very difficult for the model to be scaled up or copied. But the more serious problem that the Indian mission faced in the later eighteenth century was that it could not keep another formidably successful institution at arm’s length forever: I mean the growing territorial empire of the British East India Company. In the final lecture of this series, we will finally look directly at the subject we have been circling around all year: the inescapable, dangerous dance between missionaries and empires.

© Professor Ryrie 2022

Further Reading

Jan Sihar Aritonang and Karel Steenbrink (eds), A History of Christianity in Indonesia (Leiden: Brill, 2008)

Daniel L. Brunner, Halle Pietists in England: Anthony William Boehm and the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1993)

Robert Eric Frykenberg, Christianity in India: From Beginnings to the Present (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008)

Hendrik E. Niemeijer, ‘The Free Asian Christian Community and Poverty in Pre-Modern Batavia’, in Jakarta–Batavia: Socio-Cultural Essays, ed. Kees Grijns and Peter J. M. Nas (Leiden: KITLV Press, 2000), 75-92

Jurrien van Goor, Jan Kompenie as Schoolmaster: Dutch Education in Ceylon 1690-1795 (Groningen: Wolters-Noordhof, 1978)

Further Reading

Jan Sihar Aritonang and Karel Steenbrink (eds), A History of Christianity in Indonesia (Leiden: Brill, 2008)

Daniel L. Brunner, Halle Pietists in England: Anthony William Boehm and the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1993)

Robert Eric Frykenberg, Christianity in India: From Beginnings to the Present (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008)

Hendrik E. Niemeijer, ‘The Free Asian Christian Community and Poverty in Pre-Modern Batavia’, in Jakarta–Batavia: Socio-Cultural Essays, ed. Kees Grijns and Peter J. M. Nas (Leiden: KITLV Press, 2000), 75-92

Jurrien van Goor, Jan Kompenie as Schoolmaster: Dutch Education in Ceylon 1690-1795 (Groningen: Wolters-Noordhof, 1978)

This event was on Wed, 27 Apr 2022

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham College plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login