America's Advents

Share

- Details

- Text

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

The United States in the early nineteenth century was one of Christian history’s great moments of sectarian creativity. The religious entrepreneurs of a newly democratic society rebelled against the proliferation of denominations by creating new movements of their own, from Utopian communities to apocalyptic revivals. The most notorious such movement, the Millerites, forecast the end of the world for 1844 - in the most modern, rational and compelling terms. This lecture will explore why Millerites believed the predictions, what effects they had, and how they responded to the ‘Great Disappointment’. And it will look at how two very different but almost equally successful modern Christian movements, the Seventh-day Adventists and the Jehovah’s Witnesses, emerged from the wreckage.

Download Text

26 January 2017

America’s Advents

Professor Alec Ryrie

This is the second in a series of lectures on ‘Extreme Christianity’, which is looking at a series of movements within historic Christianity that seemed to their contemporaries to be dangerously extreme or unhinged. The point of this is, first of all, to point out that ‘extremism’ is a slippery category: it’s not just that it’s relative, in the sense everyone thinks that they themselves are sensible and that extremism is something other people do, but also that Christianity in general, and indeed religion or any other totalising philosophy, is inherently extremist. Barry Goldwater, the Republican nominee for the presidency of the United States in 1964, the last presidential nominee who fell properly outside the American political mainstream before the new incumbent, was accused of being an extremist, and famously replied that extremism in the pursuit of liberty was no vice. In 1964, that made him sound like a crazy person and helped seal his defeat, but he had a point. Substitute Christianity or indeed any other religion or ideology of your choice for liberty in his slogan and you will sooner or later find a formulation that you can agree with yourself. Religion is inevitable, in some ways, extreme, because it is absolute. What I want to do in these lectures is to look at examples of some such extreme movements, and look at how they have emerged, flourished and then either settled down or died out.

And so today we are looking at what was at its first founding, and reliably still is, one of the world’s most surprising countries, the United States of America before. In 1776 it had the nerve to declare an independence and union for a continent-sized wilderness whose scarce two and a half million people were a kaleidoscope of languages, nationalities and beliefs. Amazingly, as its population rose almost tenfold by the mid-nineteenth century, this phantasm of a country not only held together but became the richest society in human history. And it took ‘democracy’, for centuries a boo-word to all thinking people, and transformed it into a virtue. In 1828 Andrew Johnson, a future President, explained what he thought that meant: ‘The voice of the people is the voice of God. ... The Democratic party ... has undertaken the political redemption of man, and sooner or later the great work will be accomplished.’ And he looked forward to the time when ‘the millennial morning has dawned and ... the lion and the lamb shall lie down together’.

America’s democratic adventure, then, went hand in hand with its religious adventure. The United States in the early to mid-nineteenth century saw one of history’s great bursts of religious creativity. This was not the obvious direction for the new republic to take. The United States’ founding fathers were predominantly Enlightenment sceptics and deists, and the east coast’s cities were nurseries of rationalism and scepticism. But as we have been regularly reminded, America is not defined by those elites or those cities. The newly enfranchised mass population was going in another direction. Post-Revolutionary America saw a revolt against educated elites. Self-taught men and women who had had enough of experts asserted themselves against the self-satisfied and self-serving priesthoods of knowledge, in law, in medicine, in theology. The revolutionary spirit distrusted traditional learned hierarchies and valued simplicity over subtlety. This was the authentically Protestant attitude of believers who know they must stand before God, and who are confident that they can.

As America’s population surged westward, this was its religious spirit. Much of the population had no formal church membership, and managed their own religion. The printed page brought Christian community to scattered populations, as radio, television and the internet would in the future. By 1830 the United States had some six hundred religious magazines and newspapers. The old denominations were struggling to keep up with the freelance itinerant preachers. In this free market, revivalist preachers who could gather the greatest harvest would succeed. Frontier preachers often disowned any denomination, claiming simply to be Christians. Elias Smith, a self-taught Yankee preacher, insisted that properly republican churches would be democratic, respecting every believer’s conscience, with the Bible interpreted by believers’ common sense rather than by theologians’ self-serving obscurantism. Many Americans, he lamented, were only half-free, ‘being in matters of religion still bound to a catechism, creed, covenant or a superstitious priest’. His newspaper, founded in 1808, took the title The Herald of Gospel Liberty.

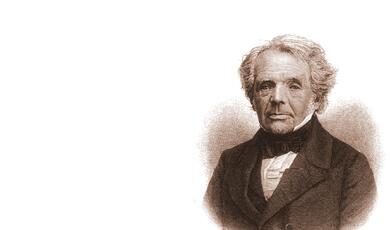

There are lots of extraordinary religious stories that began in this ferment. The best-known is that of Mormonism, but today I want to look at a story that is not so well remembered, but more characteristic of its time and, I hope I can persuade you, more significant in the world today. This is a story which begins with maybe the most archetypal religious figure in the early United States: William Miller.

Born in 1782 in the midst of the Revolution, Miller was raised in Massachusetts in poverty, in a Baptist church and with meagre education. In 1803 he moved west to Vermont. There he discovered a public library, and gave himself an eager crash course in the radical thinkers of the age. Scathing Enlightenment polemics against the Bible produced a kind of conversion, and he became a deist, a sceptic. It was the spirit of the new republic.

Then, suddenly the new republic needed more than philosophy. Miller went to fight for his country in the War of 1812, and took part in the bloody Battle of Plattsburgh in September 1814. It was a life-changing experience. The Americans, outnumbered three to one, snatched a victory, which Miller could only see as ‘the work of a mightier power than man’. But the slaughter moved him as much as the victory. ‘How grand, how noble, and yet how awful!’ he wrote. His trite deist optimism now seemed inadequate a world capable of such glory and horror. After a drawn-out crisis, he finally experienced a dramatic conversion. Stern Calvinism could explain what milk-and-water deism could not. In a dark world, ‘I saw Jesus as a friend, and my only help.’

But how was he to reconcile this new conviction with his longstanding doubts about the Bible? It was no use asking a minister to set his worries at rest: Miller had all his age’s prejudices against learned authority. So he set out to solve the problem himself: to ‘harmonize all those apparent contradictions [in the Bible] to my own satisfaction, or I will be a Deist still’. Hard work, common sense and simple faith would surely do the trick.

It worked – but with a startling side-effect. Miller succeeded in quieting his doubts, but he also made a startling discovery. Like many Bible-readers before him, he was drawn like a moth to the complex apocalyptic symbolism of the Books of Daniel and of Revelation, which seemed to lay out a tantalising map of human history. How much Miller knew about traditional interpretations of those prophecies is unclear, although he certainly picked up the idea, dating back at least to the twelfth century, that when the apocalyptic text spoke of a ‘day’, it in fact meant a year. What he brought to the problem was ingenuity, an eye for detail, and a modern, scientific conviction that God’s plan for the world is comprehensible and susceptible to numerical analysis. The pieces slowly fell into place. After many false leads and blind alleys, Miller eventually found several different calculations which led, independently, to the same conclusion. At the heart of his realisation was Daniel 8:14, which promises, ‘Unto two thousand and three hundred days; then shall the sanctuary be cleansed.’ If ‘days’ mean years; if the ‘cleansing of the sanctuary’ means Christ’s return to earth in glory; and if (as other verses imply) that 2,300 year period began with the order to rebuild Jerusalem in 457 BC ... then simple addition showed that Christ would return in glory in the year 1843.

Perhaps that makes us chuckle, but Miller was no fool. The date rested not on one single calculation, but on a complex, interlocking system of calculations, all of which could be made to point to 1843. It was bold, but not self-evidently crazy. When sceptics quoted Christ’s words – ‘of that day and the hour knoweth no man’ – Miller readily agreed: he was predicting a year, not a day or hour. The idea that this world, so full of hectic, exciting and terrifying novelties, was hurtling towards its end seemed almost self-evidently true. For millennia, prophetic excitement had been doused by the world-weary Biblical principle that ‘there is no new thing under the sun’. In this new democratic world, that plainly no longer applied. A careful, scientific analysis which both explained what the helter-skelter of recent history meant, and foretold its imminent end, was all too plausible.

Miller took a long time to convince himself that he was right, and even then was slow to act. He had no wish to become a travelling preacher, not with his fragile health. Yet the years were running short. Finally, in 1831, he began to preach his message around New England. His hope was simply to visit churches of all denominations, and persuade them that the moment for repentance was now. To his surprise, he was mocked as a fanatic. He thought his calculations, once explained, were self-evidently correct. He kept at it.

The crucial moment was the conversion in 1839 of Joshua V. Himes, a preacher with a knack for publicity. Having been convinced by the message, Himes was alarmed that Miller’s amateurish efforts were inadequate. The hour was becoming late. ‘The whole thing is kept in a corner yet,’ he protested. ‘No time should be lost in giving the Church and the whole world warning, in thundertones.’ The men formed a formidable partnership. Himes’ first move was to start a newspaper, Signs of the Times. It was the first of many: around four million copies of ‘Millerite’ publications appeared in the next four years, many of them illustrated with vivid symbols drawn from the Book of Revelation. Himes secured speaking engagements, raised funds, and distributed pamphlets. In 1842, he had a meeting-tent made, supposedly America’s largest ever, seating over four thousand. It became a kind of symbol of the movement: a colossal circus-church, both grand and, by nature, temporary.

Now the message won tens of thousands. Inevitably, it changed in the process. Miller had wanted simply to fire up Protestants believers in their home churches, but what happened to convinced Millerites whose ministers ridiculed the message? What about laymen, and women, whose churches would not let them preach, but who were too fired with the message to stay silent? What about the increasing number of new converts, who had no home church? As the movement grew it made enemies. Meetings were disrupted: tents pulled down, greased pigs set loose in crowds. Vandalism may have been to blame for the giant tent’s collapse in a storm in 1843. Those burning with advent hope began gathering together for worship, rather than sharing pews with sceptics.

Miller’s early vagueness about the precise date was now unsustainable. Under pressure, he reluctantly declared that the end would likely come between 21 March 1843 and the same day the following year. When 22 March 1844 dawned, however, Miller was philosophical: ‘we have no right to be dogmaticall … we should consider how fallible we are’. But if he could live that way, a movement built to work towards a crescendo could not. That summer, a previously obscure preacher named Samuel S. Snow declared he had found the glitch in Miller’s reckoning. The actual date of Christ’s return would be the Hebrew Day of Atonement, 22 October 1844.

The memoirs of that summer resonate with calm, solemn joyfulness. Believers put their affairs in order, giving what they could towards publicity for the cause – some holding guiltily onto reserves, others offering up all they had. One Millerite, looking back a quarter-century later, wrote: ‘not for all the world would I have missed going through my advent experience; nor for all the world would I want to go through it again’. There were visions and prophecies. One meeting was visited by strangers come to gawp at the fanatics. Instead, hearing their hosts singing, the spirit of the meeting caught them. They tried to slip away quietly, back to everyday life:

One man and his wife succeeded in getting out of doors; but the third one fell upon the threshold; the fourth, fifth and so on, till most of the company were thus slain by the power of God [i.e. they fainted]. ... Some thirteen, or more, were converted before the meeting closed.

Even the couple who had left first came back the following night, and were converted. Or so the story went. It was a season of miracles.

Himes and Miller were wary of the 22 October prophecy, but were won round by the fruit the message was bearing in believers’ lives. The prophecies of 1843, Himes admitted, ‘never made so great, and good an impression as this has done upon all that have come under its influence. … I dare not oppose it.’ The 16 October 1844 issue of his weekly newspaper, the Advent Herald, confidently declared ‘we shall make no provision for issuing a paper for the week following’. Miller, too, could not quite bring himself to endorse Snow, but conceded that ‘I see a glory in [the October date] which I never saw before’, and admitted that ‘if the Lord does not come in the next three weeks I will be twice as disappointed as I was in the Spring’.

The stories told about 22 October – the white ascension robes, the crowds gathered on hilltops – seem mostly to be malicious inventions. One believer who supposedly died leaping from a treetop into God’s arms wrote indignantly to his local paper to deny it. But the crushing emptiness of the ‘Great Disappointment’ could not be denied. ‘Our fondest hopes and expectations were blasted … we wept, and wept, till the day dawn.’ The ribald mockery of families and neighbours, no doubt a little relieved to have won their wager on scepticism, could hardly help. Some Millerites now threw over the whole movement as phoney. The doctrine that Christ’s sudden return might end the world at any time has never fully recovered from this scandal. Christ had not come. Perhaps he wasn’t going to come. The Biblical calculations had proved fruitless, so evidently the Bible shouldn’t be read that way. Perhaps it shouldn’t be read at all.

But what about those whose lives had been changed by the advent message? What if, as Himes wrote in November 1844, you were compelled to admit that God ‘has wrought a great, a glorious work in the hearts of his children; and it will not be in vain’? The simplest, hardest road was taken by Miller and Himes themselves. They admitted that their predictions had been wrong. Some went back to their Bibles for another try, but Miller warned against further date-setting. God had taught them a bitter lesson, and they should learn it. Himes, in particular, emerges from this period with some honour. Facing a slew of accusations from property-speculation to robbery, and rumours of arrest or suicide, he patiently and successfully defended his own and the movement’s honesty. He organised relief funds for those who had abandoned jobs or homes, or who had left their crops unharvested. Further editions of the Advent Herald and his other periodicals did eventually appear. And slowly, unwillingly, the ‘Adventists’ became just another denomination, a family of conservative Protestant churches, distinguished by preaching Christ’s second coming with more urgency than most others. ‘Adventism’ became an identity, based above all on shared memory of one extraordinary year. Miller ministered to this odd community until his death in 1849. Himes did so until 1876, when he finally returned to the Episcopalian church of his youth. He was ordained an Episcopal priest in 1878 and served a parish in South Dakota for sixteen years. He died in 1895, aged 90, still faithful and expectant.

But that is not the end of the story. Some Millerites could not accept that subsiding into churchly respectability was an adequate response to the glory they had glimpsed and the bitterness they had endured. Some bewildered groups tried to summon Christ by sheer force of will, forming prayer-communes until worn down by exhaustion and disillusion. One group decided that the world had now entered its Sabbath-rest and that they should therefore do no work. The men who conceived this notion rebuked the women in their community for Sabbath-breaking, and then backtracked very rapidly when food stopped appearing on their plates. Several ex-Millerites formed more enduring communes, including one near Jerusalem which endured until 1855. A number of them joined one of the best-established sectarian communities in America, the Shakers, founded in the late eighteenth century by an English prophetess and committed both to absolute equality of the sexes and to strict celibacy. The appeal of the Shakers was that they taught that Christ’s return was a gradual process, a slow dawning of which their perfect communities of disinterested love were the first glimmers, and which would, as they lived out the new world, insensibly brighten into full day. Millerites, reeling from the Great Disappointment, were ridiculed and despised by most American Christians, but the Shakers met them with sympathy and understanding. They encouraged Millerites to press on in their convictions, not to backtrack. Above all, Shakerism provided an answer to the great Adventist problem after 1844: what believers should do, other than simply wait? ‘Do you not,’ the Adventist-turned-Shaker Enoch Jacobs urged his former brethren, ‘want to find a place where Advent work takes the place of Advent talk?’ These communities were working for Christ’s second appearance, and the settled holiness of their lives was a standing rebuke to the fretted consciences of disappointed believers.

But many even of those who were drawn to Shakerism found that they were not pure enough for this austere heaven. Lifelong celibacy may have an appeal in the urgent rush of a religious conversion, or as a line to which a conscience drowning in sin can cling. But as the sun’s rise remained imperceptibly slow, the cost rose. Enoch Jacobs himself eventually left, reportedly saying that he would ‘rather go to hell with ... his wife than live among the Shakers without her’. And the Shakers continued slowly withering away.

Instead, two other groups emerged from Millerism and found ways of enduring as communities which were faithful both to the movement’s first spirit and to its new circumstances. They could hardly be more different, yet there are still certain similarities. I want to spend most of the rest of the lecture looking at them in turn.

The first was grounded on one believer’s sudden insight on the bleak morning of 23 October 1844. Hiram Edson had kept watch all night, and he now stared into the abyss:

I mused in my own heart, saying, My advent experience had been the richest and brightest of all my Christian experience. If this has proved a failure, what was the rest of my Christian experience worth? Has the Bible proved a failure? Is there no God – no heaven – no golden home city – no paradise? Is all this but a cunningly devised fable?

Instead, as he prayed with renewed urgency, Edson was given an explanation in a vision. Miller’s calculation had foretold when the sanctuary would be cleansed. What Edson now understood was that that did not actually refer to Christ’s return to earth. The date had been right after all! Christ had now entered the heavenly sanctuary, the Holy of Holies, in final preparation for the last judgement. The world might look the same, but while the Millerites had wept and prayed the night before, it had moved a decisive step closer to its end.

It was a very satisfying solution, allowing Adventists to affirm the message they had first believed while explaining its apparent failure, and Edson rushed it into print. It was taken up by a seventeen-year-old Millerite from Maine named Ellen Harmon. In December 1844 she had a vision, in which Adventists were walking on a narrow way towards the new Jerusalem, their eyes fixed on Christ. Some, however, now ‘rashly denied the light behind them, and said that it was not God that had led them out so far’. Those poor fools stumbled and fell off the path into darkness. Those who embraced Edson’s sanctuary doctrine remained on the straight and narrow.

Harmon then added two further doctrines. One was the ‘shut door’: during this, presumably brief, interlude between Christ’s entry into the sanctuary and his final return, the door was shut on fresh conversions. The world had had its chance before 22 October. This meant that Harmon’s efforts were focused exclusively on the scattered Adventist community. The other addition came in a vision in which Jesus showed her the original tablets of the Ten Commandments. One of the ten was encircled by a halo: ‘Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy’. She understood this to mean that she ought to abandon the Christian tradition of worship on a Sunday, a tradition which is very ancient but is not actually taught in the Bible, and return instead to the Biblical Sabbath on Saturday, the seventh day of the week. That was a disruptive challenge to social norms, and Harmon’s little band, badly needing to distinguish themselves sharply from a sinful world, adopted it. Perhaps this was the last step in their purification before the sanctuary was cleansed.

The Joshua Himes to Ellen Harmon’s Miller was a young preacher named James White, her chaperone, her publisher and then her husband. They were a formidable team, not least in turning a movement a very short-term outlook into one capable of functioning indefinitely. By 1851, the ‘shut door’ was becoming a problem: new converts were not only being won but being born. A rigidly consistent movement might have withered, but the Whites recognised the new situation and quietly dropped the ‘shut-door’ doctrine. They had also disowned any further date-setting. The reason Christ had entered the sanctuary in 1844, Ellen was told in a vision, was to conduct his ‘investigative judgement’: working steadily through the record of humanity’s sins in advance of the end. By its nature, this might take a while. Rather than playing guessing-games with the calendar, they should use this providential delay to make themselves a truly holy people.

In 1860, reluctantly, this community became an organised denomination. The name they chose – the Seventh-day Adventists – encapsulated they distinctive double focus. Their eyes remained fixed on Christ’s imminent return, but in the meanwhile they urgently pursued personal and corporate holiness, of which the Saturday sabbath was only the most prominent symbol. Indeed, in the 1860s, that quest for holiness took a new direction. Ellen White had long suffered from poor health, and like many other American Protestants, she distrusted the learned priests of medicine as well as those of theology. Many Adventists expected miracles of healing in these latter days, and some toyed with rejecting human medicine altogether, but White was too level-headed for that. She accepted that God worked through human medicine. She did not, however, mean the medicine practised by learned and expensive MDs. It was not merely socially exclusive and cruelly ineffective: it also offended her notions of purity, simplicity and natural perfection.

This was republican suspicion of learned elites in another form. The quest for health as spiritual purity was a widespread theme in nineteenth-century America, and Ellen White now picked it up with verve. As well as denouncing alcohol, as many other Protestants did, she urged Seventh-day Adventists to abstain from the ‘filthy weed’ tobacco, and even disapproved of tea and coffee, dangerous stimulants which fostered a tendency to gossip. Abstaining from pork became an invariable rule. She herself eventually abandoned all meat, and for a time also eggs, cheese and cream, although unlike some of her disciples she continued to permit milk, sugar and salt.

Diet was only the beginning. White was also a convert to hydrotherapy, a technique which consisted chiefly of wrapping yourself in soaking bandages and in drinking copious quantities of pure water. She credited this harmless technique with saving two of her sons from a dangerous illness in 1863, and a vision led her to declare the merits of ‘God’s great medicine, water, pure soft water, for diseases, for health, for cleanliness, and for luxury’. She also had firm views on sexual health, such as the dangers of excessively frequent sex. This mother of teenage sons was particularly vehement against masturbation, which she blamed for ‘imbecility, dwarfed forms, crippled limbs, misshapen heads, and deformity of every description’. She also had stern views on dress, and her recommendation of a ‘short’ (calf-length) skirt for women, with loose-fitting trousers worn beneath it, was as scandalous in her age as public nudity would be in ours.

Health reform became a central means, not only of purifying Seventh-day Adventist believers, but of adding to their number. The church began to publish journals such as The Health Reformer aimed at a general reader, and to establish sanatoriums and spas where patients could be gently introduced to the sect’s beliefs. One result of this was the long and fruitful, though eventually unhappy, partnership between Ellen White and John Harvey Kellogg, nutritionist, health reformer and the inventor of cornflakes. White, who did not particularly like cornflakes, turned down the opportunity for the church to own the Kellogg’s brand. It was a costly but perhaps fortunate decision. Having kept her church’s soul pure throughout her long life – she finally died in 1915 – it would have been a shame to have sold it for breakfast cereal.

That near-miss is a sign of perhaps the most remarkable fact about Seventh-day Adventism: its astonishing gift for avoiding trouble, a lot of which has to be put down to Ellen White’s own legacy of level-headed pragmatism. It has escaped vanishing into extremism, while maintaining a distinctive identity. So it has moved from its early view that the USA is one of the anti-Christian beasts described in the Book of Revelation to a more constructive, pragmatic apoliticism. It has never allowed its apocalypticism to tip it into madness, although some of its splinter groups – most notoriously, the Branch Davidians who were immolated in Texas in 1993, who came out of a Seventh-day Adventist milieu – show how easily it could have happened. Nor did Adventist health reform take the blind alley represented by White’s near-contemporary, Mary Baker Eddy. Her superficially similar Christian Scientist movement became trapped in a ghetto by her occultish preoccupations and her blunt rejection of medicine. The Adventists, by contrast, were able quietly to abandon quackery and fully embrace mainstream medicine in the twentieth century.

One thing has remained constant: growth. Seventh-day Adventism has grown from some 200 in 1850, to 3500 in 1860, to 75,000 worldwide by 1900, to – by dint of steadily doubling in size, or more, every fifteen years – some eighteen million at present. Without attracting attention, they have come to outnumber much more prominent groups like the Mormons, and have quietly mushroomed into one of the world’s major Protestant denominations. They have also moved closer to the Protestant mainstream, and can sometimes seem simply like conservative Protestants who happen to worship on Saturdays. They are carefully apolitical and exceptionally multiracial. Even so, they still stand apart. It is, in practice, impossible to be a Seventh-day Adventist in good standing unless you accept Ellen White’s vision, and Adventist historians who have delved too deeply into her career have found themselves ostracised. They have made peace with the world: but they have not surrendered to it.

The second modern group to emerge from Millerism could hardly be more different. They are latecomers. Charles Taze Russell, the movement’s founder, was only born in 1852, in Pittsburgh, and as a teenager was converted to mainstream, post-1844 Adventism, Miller and Himes’ tradition. Naturally, the young Russell turned to self-taught study of Biblical chronology, hoping like many others to find the flaw in Miller’s calculations. By 1876, he had an ingenious solution. One of Miller’s supporting arguments for his 1843 date had been a tenuous calculation that there would be an interval of 2,520 years following Israel’s enemies reigning over her. Miller counted from the year 677BC, when the first exiles were deported from Jerusalem, reaching 1843. Russell argued that much more natural start date would be the actual fall of Jerusalem in 606BC. That pointed to a new crux year: 1914.

Russell was hardly the first to come up with a new date. What set him apart was a separate set of calculations, based on the ancient Jewish years of jubilee. This led him to conclude that Christ’s rule on earth would begin not in 1914, but forty years earlier, in 1874. That year had recently passed without obvious cosmic incident. However, that fact, far from torpedoing Russell’s theory, became central to it. He preached, not Christ’s second coming, but his second presence on earth, a slow process which had already begun. During the years until 1914, Christ would slowly harvest the souls of his faithful, eventually making up the prophetic number of 144,000.

Like most sect founders, the last thing Russell wanted was to found just another sect. His ambitions were bigger. His disciples were known with studied humility as ‘Bible students’: their findings were for everyone, and should not be confined behind denominational walls. They would keep that anonymous title until they adopted the modern term ‘Jehovah’s witnesses’ in 1931, and that too was meant to be a plain description: people who bear witness to the God whose name is Jehovah. What Russell founded was not a church but a publishing enterprise. He began with a self-published book in 1877, and in 1884 established the Zion’s Watch Tower and Tract Society as a legal corporation. It is a very American way of forming a sect. As a corporation, the society, renamed the Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society in 1896, has unchallenged legal rights over its publications and a simple, autocratic structure. As a result, under Russell and his successors as president, the Witnesses have become both the world’s most rigidly controlled large-scale Christian movement, and also by far the most persecuted Christian movement in modern times.

Russell’s understanding of that window of opportunity before 1914 gave his ‘Bible students’ their ethos. His Bible students’ priority was not to win fresh converts to Christianity, but to call nominal Christians out of their false, Babylonical churches while there was still time. Distinguishing his movement from those churches became a central concern. So, like other anti-sectarian sectarians before him, he rejected the Trinity, which he called ‘the unreasonable theory that Jehovah is his own Son and our Lord Jesus is his own Father’, thus giving his own movement and the mainstream churches an enduring pretext for loathing each other. Hence, too, his self-conscious use of the word Jehovah. That is simply the traditional Latin form of the Hebrew name of God, but for Russell it became a way of asserting both that Jesus, who has a different name, is ‘a god’ rather than actually God. It was also another marker of his movement’s difference from the other churches.

The need to fill up the numbers of the faithful gave Russell’s Bible students their sole, single-minded priority. They lived to bear witness to the truth, regardless of whether they were believed. After all, if there will be only 144,000 chosen, most of humanity will spurn the message. The legions of Witness ‘publishers’ who work door-to-door and in public places across the world do so in deadly earnest, after careful training in managing difficult encounters and turning conversations so as to have a chance to save another soul. But they neither expect a high rate of success nor regard rejection as a failure, and find camaraderie in shared tales of doorstep rebuffs. Their responsibility is to bear witness faithfully, whether or not that witness is heard. Later Witnesses told of how Russell himself, as a young man, ‘would go out at night to chalk up Bible texts in conspicuous places so that workingmen, passing by, might be warned and be saved from the torments of hell’. In the 1920s, American Witnesses sometimes descended on quiet neighbourhoods with loudspeakers, so that shut doors could be no barrier to the Word. This is proclamation whose primary purpose is proclamation itself.

That also provided the answer to Millerism’s unanswered question: how should you live, in the shadow of Armageddon? Seventh-day Adventists reached for the purity of health reform. Russell’s movement found a different kind of purity: behind the ceaseless activity of preaching was the austere, almost monastic holiness of scrupulous separation from the world. Nations, churches, families were all shortly to be judged and destroyed. True students of the Bible should, therefore, renounce them all. They would not openly defy governments, but nor would they collaborate with them through military service or even through voting. Instead, they would bear witness through rigid refusal to conform to this world’s norms.

But there was a problem: the pre-printed expiry date of 1914. As the year grew closer, Russell began to backpedal, but his earlier predictions had been very specific. If he had lived longer, his movement might have disintegrated. Instead, following his death in October 1916, the Society’s presidency was seized in a boardroom coup by Joseph Franklin Rutherford, the movement’s second founder. Dubiously claiming Russell’s authority, Rutherford now argued that 1914, like 1874 before it, was the beginning of a process. For while the world had not actually ended in 1914, that year did indeed bring a global catastrophe of Biblical proportions in which the world’s corrupt nations set about each other’s destruction. It was not ridiculous to conclude that the final end was near. In early 1918, Rutherford delivered a speech, later a tract, titled ‘The World has Ended — Millions now living will never die!’. It was time for Jehovah’s witnesses to separate themselves from the world’s death throes. As the United States entered the Great War in 1917, Rutherford vehemently denounced both the war itself and its cheerleaders in the mainstream churches.

He and seven of the Society’s other directors were arrested, found guilty of sedition and given lengthy prison sentences. They were released in 1919, but by then the war had ended and the world had not. Rutherford tried to revive the Society with a further prediction that the end would finally come in 1925. When that prophecy too failed, without even a near-apocalyptic global event as consolation, the movement reached its lowest ebb.

So Rutherford reinvented it. Along with the new name, in 1931, went central control of the appointment of elders in local congregations. Teaching offered in those congregations would now be uniform across the globe. Russell’s original works, many of them embarrassingly obsolete, were allowed to go out of print for good. Publications began to appear anonymously, as the collective, unchallengeable wisdom of the Watchtower Society, which in 1927 declared itself to be God’s ‘faithful and discreet slave’, with authority to determine matters of faith. Its new books typically had sweeping one-word titles such as Life, Riches or Vindication. The Witnesses’ apocalypticism was undimmed, but there has been no further authoritative date-setting. There have been excitements around other dates, in particular 1975, but nothing official. For most of the twentieth century, the Society simply held tight to 1914, declaring week by week in its main magazine that the new world would dawn ‘before the generation that saw the events of 1914 passes away’. In 1995, this increasingly implausible claim too was redefined, explaining that ‘generation’ was a spiritual rather than a literal term.

We might have thought this would be embarrassing, but the Witnesses have continued to grow, and at present number around eight million active members worldwide (the numbers are contested). The driver is not the fading apocalyptic predictions, but the continued insistence on aggressively distancing themselves from social and religious norms. This is the logic underlying some otherwise rather peculiar stances: such as the insistence that Jesus Christ was killed on a stake rather than being anything so popish as a cross, or the insistence, introduced only in 1945 and on rather shaky grounds, that Witnesses may not receive blood transfusions. What all of these and other policies do is to assert a highly visible difference with the outside world. For this, they have been duly reviled by churches and especially by governments. Nazi Germany murdered over five thousand of them, a large percentage of the German total, although, uniquely among the Nazis’ victims, they were given the chance to save themselves by renouncing their faith. At the same time, Witnesses in America and the British Empire were being imprisoned for conscientious objection and being accused of being Nazi sympathisers. Since 1945 it has been Communist states of various kinds that have been the most active persecutors.

It is not easy for outsiders to love the Witnesses. It is impossible not to be moved the stoicism by which they have endured persecution, but enduring and even courting persecution is important to their identity. There is a large constituency of ex-Witnesses with little good to say about the Society. But there is more to the Witnesses than hostile caricature admits. Their determined internationalism and disregard for racial differences has made them at present amongst America’s most racially integrated religious groups. They are also capable of winning real respect from their neighbours, especially in tough social environments. When other churches have reputations for clericalism, hypocrisy or financial corruption, the Witnesses can justly boast that they have no paid ministers, take no collections and maintain strict moral discipline. The rigorous training which all Witness ‘publishers’ undertake, from detailed although carefully directed study of texts to sharing in leadership, can be as rewarding as it is demanding. Outsiders do not need to admire or agree with the Society, but they should try not to hate it, if only because hatred is one of the fuels on which it thrives. Neither Witnesses nor mainstream Protestants like to admit it, but they belong to the same extended family. And there are some hints that, like the Seventh-day Adventists, they too are subject to the gravitational pull of social normalisation. In 1996, the Society gave permission for Witnesses facing military conscription to perform civilian service in lieu. The growing numbers of ‘passive’ Witnesses, who are not active publishers but remain members of the community, represent a bridge with the outside world which the Society has striven to keep out, and there is plenty of evidence that such believers often hold much more tolerant and inclusive views than they are formally supposed to.

William Miller did not know what he was starting, and the story is a long way from over, but by way of an interim report we can say this much. His movement was grounded in a theological, Biblical argument, but what really gave it its energy was an experience, a shared moment of inner renewal as his people lived in the shadow of the advent in 1844, an experience which even convinced Miller himself against his better judgement. And it was thanks to that experience that it did not merely flare and disappear, for even when it became unavoidable that his predictions were not literally true, too many people had found a deeper truth in them that they were unwilling to let go of it. Religious communities can live off little more than the memory of grace for a long, long time. Yet even so, this ought to have been a mere echo, a slow fading into the background, and it would have been had two of the strands of that echo not stumbled across radically different ways of giving themselves enduring institutional expression. Both of them found answers to the question, not only of what people ought to believe, but how they ought to live, that proved satisfying in the short term and viable in the long term to enough people that they have thrived and spread. So that, should you be looking to found one, appears to be the recipe for a successful sect. What neither the Adventists nor, apparently, even the Witnesses have managed to do is to find a fool proof way of stopping themselves decaying, or mutating, or developing into what every extremist movement most fears becoming: just another church.

©Professor Alec Ryrie, 2017

Gresham College

Barnard’s Inn Hall

Holborn

London

EC1N 2HH

www.gresham.ac.uk

Part of:

This event was on Thu, 26 Jan 2017

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham College plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login