Attacks on Knowledge from Ashurbanipal to Trump

Share

- Details

- Text

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

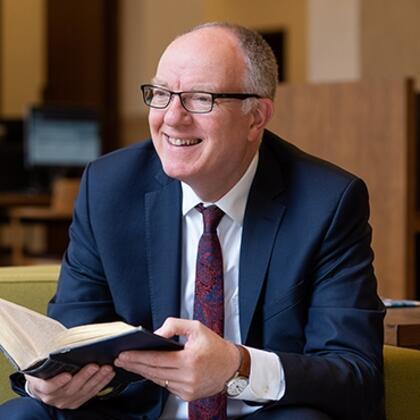

This lecture explores the destruction of libraries, archives and other knowledge, from Babylonian times until now, and its implications for society today. What are the motivations for destroying knowledge, and how have libraries and archives responded to these threats? What must we do now that knowledge is digital, and controlled by a small number of very powerful companies?

Download Text

On 10 May 1933, a bonfire was held on Unter den Linden, Berlin’s most important thoroughfare, close to the Berlin State Library. It was a site of great symbolic resonance: opposite the university and adjacent to St Hedwig’s Cathedral, the Berlin State Opera House, the Royal Palace and Karl Friedrich Schinkel’s beautiful war memorial. Watched by a cheering crowd of almost forty thousand, a group of students ceremonially marched up to the bonfire carrying the bust of a Jewish intellectual, Magnus Hirschfeld (founder of the ground- breaking Institute of Sexual Sciences). Chanting the ‘Feuersprüche’, a series of fire incantations, they threw the bust on top of thousands of volumes from the institute’s library, which had joined books by Jewish and other ‘un-German’ writers (gays and communists prominent among them) that had been seized from bookshops and libraries. Around the fire stood rows of young men in Nazi uniforms giving the Heil Hitler salute. The students were keen to curry favour with the new government and this book-burning was a carefully planned publicity stunt. In Berlin, Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s new minister of propaganda, gave a rousing speech that was widely reported around the world:

“No to decadence and moral corruption! Yes to decency and morality in family and state! . . . The future German man will not just be a man of books, but a man of character. It is to this end that we want to educate you . . . You do well to commit to the flames the evil spirit of the past. This is a strong, great and symbolic deed.”

Similar scenes went on in ninety other locations across the country that night. Although many libraries and archives in Germany were left untouched, the bonfires were a clear warning sign of the attack on knowledge about to be unleashed by the Nazi regime. The Nazi regime would move this act of destruction from the merely theatrical to the industrial scale and it has been estimated that over 100 million books were destroyed during the Holocaust, in the twelve years from the period of Nazi dominance in Germany in 1933 up to the end of the Second World War.

But the staged book-burnings provoked a response among those who saw the need to defend the freedom of expression. In fact, two new libraries were formed as a counterblast. A year later, on 10 May 1934, the Deutsche Freiheitsbibliothek (German Freedom Library, also known as the German Library of Burnt Books) was opened in Paris. The German Freedom Library was founded by German-Jewish writer Alfred Kantorowicz, with support from other writers and intellectuals such as André Gide, Bertrand Russell and Heinrich Mann (the brother of Thomas Mann), and rapidly collected over 20,000 volumes, not just the books which had been targeted for burning in Germany but also copies of key Nazi texts, in order to help understand the emerging regime. H. G. Wells was happy to have his name associated with the new library, which became a focus for German émigré intellectuals and organised readings, lectures and exhibitions, much to the disgust of German newspapers. Following the fall of Paris in 1940 the library was broken up, with many of the volumes joining the collections of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. The Brooklyn Jewish Center in New York established an American Library of Nazi-Banned Books in December 1934, with noted intellectuals on its advisory board, including Albert Einstein and Upton Sinclair. The library was proclaimed as a means of preserving and promoting Jewish culture at a time of renewed oppression.

These attacks on knowledge were a cultural and intellectual genocide that prefigured the human genocide that would soon follow. The Nazis, however, have not been alone over the past century among anti-democratic regimes in targeting knowledge – either through misinformation, destruction, or theft.

One of the particular triggers for me writing the book was of course back in January 2017 the inauguration of President Trump and the allegations that were made by Kellyanne Conway, his Press Secretary that against the facts that he had fewer people attend his inauguration than had attended President Obama's, that they were, and I quote, "alternate facts."

The particular trigger that caused me to write the book was the destruction of the landing records of the Windrush generation by the Home Office in 2010, at the same time that the Home Office were instigating their ‘hostile environment’ against our fellow citizens, at least 80 of whom were unlawfully deported, based on the fact that they lacked the evidence to prove their right to remain. Whereas in fact the Home Office all this time had not only the possession of the landing cards that could prove their right to remain, but actually chose to destroy them.

"There was truth and there was untruth and if you clung to the truth even against the whole world you were not mad."

Although my book and this lecture are really concerned with the social importance of the preservation of knowledge, and I think of libraries and archives as institutions that help society to ‘cling to the truth’.

So, with that backdrop what I would like to take us on a short journey back through history, to look at what lessons we can learn from previous historic attacks on knowledge and what it tells us about the importance of the preservation of knowledge and the institutions of libraries and archives that society has entrusted that role to.

I was fortunate in going to visit the British Museum's wonderful exhibition ‘I Am Ashurbanipal’ a couple of years ago and was really struck that at the heart of this exhibition was a library – but one unlike any I had seen in my 30 years as a librarian. I hadn't previously encountered the rich and interesting history of how knowledge was preserved and organised in libraries and archives in ancient Mesopotamia at all, so it was a revelation for me at the time and I was absolutely delighted to find that our sister institution the Ashmolean Museum has fabulous holdings of cuneiform tablets.

Here are a few which Paul Collins, my colleague in the Ashmolean Museum, kindly looked out for me to consult. I don't know if many of you saw that exhibition at the British Museum but right in the heart of it was a library. In a museum exhibition it's quite surprising to see this incredible library of stone tablets formed by Ashurbanipal and looking at in more detail, going to read up, going to talk to my colleagues about the history of libraries and archives it became clear that not only were they absolutely vital parts of society going back five millennia, but they were also formed through acts of destruction, deliberate theft and the breaking up of other libraries.

There are accession records for Ashurbanipal’s Library which have been studied by scholars working in this field which show that he was deliberately targeting libraries and archives in neighbouring states especially Babylonia and sending his agents to go either forcibly or through diplomacy to seize documents from these other libraries to build his own knowledge base up. Part of the content of these ancient libraries concerned the prediction of the future, about astronomy, astrology, and divination, and that's something I'd like you to hold on to, that the sense that libraries control vital knowledge that brings power with it. We will come back to it at the end of this talk.

If you're able to remove knowledge from your enemy, you can not only make them weaker, but you can make yourself stronger. Our knowledge of these libraries and archives has emerged since the middle of the nineteenth century, when a series of excavations begun by French archaeologists, not that they would have called themselves that at the time, and then most importantly by a Briton: Austin Henry Layard, who did amazing excavations in the ancient capitals of Nimrud and Nineveh in what is now Iraq and brought tens of thousands of tablets, the contents of these ancient libraries and archives, back to the British Museum. He was known as ‘the lion of Nineveh’ and became incredibly famous at the time.

One cannot discuss attacks on knowledge in the ancient world without making reference to the Great Library of Alexandria. For millennia, the greatest library in the ancient world – in Alexandria has been assumed to have been destroyed in a catastrophic conflagration. The ancient writers were in fact divided on even the basic issues about the library - including its size, and the causes of its demise. All they really agreed on was that it was larger than any other library they knew of, and that great scholars came to work there – such as Euclid the founder of modern mathematics – here is the oldest surviving copy of his great work - the Elements of Geometry, written in the 9th century in Byzantium and now in the Bodleian. What modern scholars agree on is that the library did not go up in flames in a single terrible event, but declined slowly, over a long period of time, reduced to nothing through neglect and under-funding, so that by the 4th century of the Christian era the library was completely gone, just a memory.

I'd like us to do some more time travel now, further through history to one of my other case studies, which is the library of Glastonbury Abbey in the sixteenth century, and the particular figure I'd like us to focus on is John Leland.

Leland was an astonishing character. He doesn't feature in Hilary Mantel's great trilogy about Thomas Cromwell and Henry VIII, but he really ought to have done. Educated both at Cambridge and Oxford and then later at the University of Paris, he became steeped in humanism and very interested in investigating primary sources of the past. Henry VIII tasked him with a ‘most gracious commission, to peruse and most diligently search all the libraries’ of the monasteries and colleges in the country, as part of the King’s so-called ‘Great Matter’, the search for information to help him win his case for the divorce of Catherine of Aragon and to enable him to marry Anne Boleyn, and later to argue for the divorce of the whole country from Papal authority.

We are fortunate in the Bodleian to have the archive of John Leland. In these papers you can find records of his journeys, the so-called itineraries. These are extraordinary documents listing the places he visited, sometimes with maps that he drew to help plan the journeys, here for example you can just see the Humber Estuary and the houses in Lincolnshire and East Yorkshire that he visited, and then made detailed notes of the books that he saw. Leland’s archive provides an extraordinary snapshot of the medieval libraries of Britain on the eve of the Reformation, even though he didn't realise that through his research visits he was party to their destruction.

So let us follow Leland to Glastonbury. This is my rather amateurish photograph of what remains of the library of Glastonbury Abbey today. At the time it really was one of the most important religious houses in the country. In size it was actually bigger even than Canterbury Cathedral, and it was of course a great pilgrimage site, with associations to the mythical King Arthur, to Merlin and to Joseph of Arimathea. So, it attracted great wealth, many donations from pious pilgrims, but it also built up an extraordinary library. And it was one of the libraries that Leland was most excited to go to visit.

Leland actually gives us a description, of his visit the library in 1533 or 1534. "I had hardly crossed the threshold" he wrote, "when the mere sight of the most ancient books left me awestruck, stupefied." He literally swooned just at the mere sight of these ancient books in the library, and he became great friends with the abbot Richard Whiting, the last Abbot of Glastonbury. He recalls in his notes how generous Whiting was in showing him books and giving him hospitality in his visit, and he even leaves us notes of the books that he looked at. Some of them were ancient chronicles which were to help prove that there was a viable Church in England, before the Norman Conquest, indicating the antiquity of an alternative to Papal authority, but he also found there many of sources which helped him unearth the history of King Arthur. But also, there he found a book which he was greatly interested in which was this one.

Again, very fortunate to have it in Bodleian. It's now known as Saint Dunstan's class book and it's actually a miscellany. There are four volumes in it dating from the ninth to the tenth century, three of which were almost certainly owned or used by Saint Dunstan, Abbot of Glastonbury, and then later Archbishop of Canterbury, a very important figure in the reform and modernization of the Church in England in the ninth century. And here we can see actually there's an image of Saint Dunstan kneeling at the foot of Christ, arguably the earliest self-portrait in English art.

And here we can see a list of some of the books that Leland consulted in the library of Glastonbury Abbey, and right at the bottom you see ‘grammatica Euticis liber olim Sancti Dunstani’. We know that the book was in the library of Glastonbury in 1249 when it was listed in the medieval catalogue, and then we see in 1533-1534, Leland actually consulting that volume, and now it's in Oxford in the Bodleian, thanks to antiquaries -individuals concerned to preserve the past.

Now of course what happened is absolutely tragic for the Library of Glastonbury Abbey. In 1539 we have a visitation of the commissioners following the act for the suppression of the Greater Monasteries and the commissioners come to visit Glastonbury Abbey and Abbott Whiting and they present trumped up charges that he robbed the Church of Glastonbury of treasure and he was duly tried, taken up to Glastonbury tour after being dragged through the town on a hurdle and there he was hung drawn and quartered and bits of his body were placed in neighbouring towns: Wells, Taunton and Glastonbury itself, so not a very happy end but then of course the monastery itself was dismantled and the books - we don't know exactly how many there were in 1533-1534 when Leland visited, but they were probably at an estimate I would say about around 1500.

A mere 60 volumes are known to survive today. From contemporary accounts we know that many of them were torn up and sold. Some sold to grocers and soap sellers said Leland's friend John Bale. Some were sold to book binders to strengthen book bindings. So, these volumes cease to have value other than as waste material, and so we are very lucky to have a number of books from the medieval library at Glastonbury which have come through the activities of antiquaries, and many of these antiquaries became part of a reaction against the destruction of knowledge during the Reformation.

I’d like to take us to my own institution, the University Library in Oxford. Originally founded in 1320 by Thomas Cobham, Bishop of Worcester, in a room in the University Church specially constructed as a library. It grew during the Middle Ages through numerous gifts, especially a spectacular one in the middle of the 15th century from Humfrey, Duke of Gloucester, one of the most powerful laymen in the country, someone deeply interested in humanistic learning. In order to make room for almost 300 new books from Duke Humfrey’s gift, the University authorities built a new library – a beautiful space, still called Duke Humfrey’s Library today – which first opened to readers in 1488. But this library was attacked in the second phase of the Protestant Reformation, by the Commissioners of Edward VI in 1549-1550. Again, the books were mostly sold for scrap materials, and only a handful escaped with Catholics fleeing to the Continent.

What followed was a reaction against this wholesome and ideologically driven destruction of knowledge. Sir Thomas Bodley, from a staunchly Protestant family, an Oxford graduate, and someone who had considerable private wealth, and who was well connected in the Court of Elizabeth I came along in the 1590s and set about re-establishing the library. His refounding of the library had significant special features. The statutes of the library placed preservation absolutely at the heart of the library’s mission. But also access making knowledge available to what Sir Thomas called ‘the whole republic of the learned’ was key – the library was one of the few in Europe open to scholars from outside the University, and the Bodleian published a catalogue of its holdings as early as1605. Bodley, moreover, directed all of his funding, his own wealth to endow the library to provide for ‘officers stipends, the augmentation of books and other pertinent occasions’. He wanted his institution to endure and not to suffer, as he had seen the fate of so many libraries during the Reformation.

I'd like us to move forward now into the nineteenth century to another episode of the destruction of knowledge, the burning of the Library of Congress in 1814. I'd like to introduce you to Sir George Cockburn, Rear Admiral Cockburn, who led a British expeditionary force to the United States, to the former colonies, and this mezzotint has, in the background, this most extraordinary picture of the burning of Washington in August 1814.

I'd like to quote you from another Oxford figure, a Balliol alumnus called George Gleig who was there as a British soldier at the time, and he wrote: "I do not recollect to see more striking or sublime than the burning of Washington". But he also was rather ashamed that the troops of which he was one also set fire to "a noble library, several printing offices and all the national archives which were committed to the flames, which might better have been spared", so he later admitted.

And so, the destruction of the library and here's a view of the Capitol building which housed the senate and the House of Representatives and the library itself. After the fire it was actually the only stone building in Washington at the time and it housed the only library in the city. The Library of Congress had been founded in 1800, the first librarian appointed a few years later and the collections had been slowly built up to the point in 1814, that the 5,000 or so volumes provided a very useful set of combustible materials to start the fire.

We actually have one of the books which was saved – not from the Library of Congress but from the Office of the President in the Capitol building, and which was taken as a souvenir by one of the British troops. It seems to have been taken by a soldier, who regarded it as the ‘spoil of the conqueror’ and given to Cockburn.

What happened after the events of August 1814 was another response to destruction, and a further indication of that human impulse for preservation and renewal. That response came from Thomas Jefferson, one of the founding fathers of the United States, and a former President, who had retired to his estate at Monticello in Virginia. He heard about the fire and wrote an absolutely scorching letter to a newspaper in Washington saying that this was an act of barbarism and he offered his own library, really the greatest private book collection in the United States at the time, to be purchased by Congress to replace the lost library. After months of political wrangling, Congress eventually agreed to the purchase, and Jefferson ended up selling six and a half thousand volumes for the princely sum of twenty-four thousand dollars. Quite an enormous sum at the time but it gave the new Library of Congress an absolutely head start, with vital books for government to use to help it manage its national affairs. Unfortunately, this library then suffered another accidental fire in 1851 and the result of that: Congress voted much bigger funds to rebuild the Library of Congress and make it the great institution that it is today. But the burning of the library remained an important part of the national myth of the United States long into the nineteenth century.

Almost exactly a century on from the destruction of the Library of Congress there's another noteworthy attack on knowledge which became an international incident in the way that the burning of the Library of Congress really didn't and that's the destruction of the Library of the Catholic University of Louvain in August 1914.

Soon after the start of the War, the German army marched into neutral Belgium. They occupied the beautiful, ancient city of Louvain (modern day Leuven), which many called the Oxford of Flanders, because of its combination of attractive architecture and famous University. In August 1914 the German troops set fire to the historic centre of the city, and indeed started it with in university library, which was destroyed. Almost all the collections went up in flames. The University library dates back as an institution to the 1630s. It was re-founded in 1835, became one of a number of legal deposit libraries for the (then) new country of Belgium and the events of August 1914 triggered an international outrage.

Here's a scene of the wreckage of the library. And all over the world the news of the burning of the library was met with outrage and horror. This is from an Irish newspaper, but this example could have been taken from newspapers in any number of countries – again the loss of the Library of Alexandria is evoked

Although this episode in World War One has for the most part been forgotten today, at the time it was a huge story. Here you can see that I put the term ‘Louvain’ into Google books ngram viewer, revealing the spike for the number of times that Louvain is cited in printed publications in the second part of the teens of the twentieth century.

One of the interesting things about this story was the reaction to the great conflagration. An international movement to raise funds and to donate books to give to the library was begun, which became. It becomes a special clause in the Treaty of Versailles whereby Germany is charged with replacing the destroyed books, and the Americans take the library’s renewal as an opportunity for projecting soft power in Europe after the First World War. They commit to raise the funds to rebuild the physical structure of the library. This task was led by Nicholas Butler, the President of Columbia University.

Butler’s Committee chose an American architectural practice, Warren and Wetmore, here is an architect's drawing of the rebuilt library, modelled on the original library just really a kind of a pastiche or facsimile of that original building which the Americans pledged to raise money for. You can see in this architect's drawing in the little cartouche at the bottom: ‘Destroyed by the Germans in 1914. Restored by America in 1922.’

So this is seen an important opportunity for America to influence European affairs, but actually it took them much longer to raise the money than they had originally planned, with John D Rockefeller eventually supplying the shortfall himself, and by the time that they finished raising the money, in the late 1920s, the post-war diplomacy between Belgium and Germany had begun to see a burying of the hatchet, so-to-speak, and the acts in Louvain in 1914 began to be purposefully ignored or downplayed by Belgians.

The Americans wanted to have a big grand opening ceremony with a massive plaque saying this phrase in Latin - that the building was destroyed by the Germans, rebuilt by the Americans, but it became a national point of tension. American architects put this plaque up several times and local Belgians climbed up in the middle of the night and smashed the plaque because they did not want it to colour the relations that they have with their neighbours, and eventually the plaque was removed and placed in a war memorial. The library was finished: rebuilt and modernized.

The Louvain Library was incredibly important to Belgium, as a national symbol – a place of culture, but also a place of learning by the young, an institution, therefore, dedicated to the future. So, there was a great effort to rebuild the library, and to restock it with books, an international effort that was supported by libraries and readers all over the world, and by librarians – a national campaign in Britain was led by Henry Guppy the librarian of the John Rylands Library in Manchester.

But sadly in 1940 the library was destroyed a second time, and again by the German army. This time artillery targeted on the library sees it destroyed and it then had to be rebuilt after World War Two, again. But again, they choose to rebuild it in the same original vernacular style. It remains a vibrant University Library.

The Holocaust, I think, is one of the episodes in history where the catastrophic destruction of knowledge takes place. There is one particular episode that I think is really interesting in highlighting the importance of preserving knowledge and how individuals and communities take this task so seriously that they're willing to risk their lives to preserve knowledge.

Vilna, or modern-day Vilnius, in Lithuania, was, at the beginning of the twentieth century one of the great centres of Jewish civilization and it's also a city full of books and archives, such as the Strashun Library, formed but a bibliophilic Jewish businessman at the end of the 19th century, and left to the Jewish community in Vilna. On the eve of World War Two it had a busy reading room, and a learned librarian. But Vilna also had a great archival institution, a research institute into Yiddish culture, into the cultural life of everyday Judaism in Central and Eastern Europe, called YIVO. YIVO begins to collect oral histories, music hall posters, documents like medical case notes and even the diaries of Theodor Herzl, the founder of Zionism. And then of course in 1939 Lithuania and the other Baltic States and Poland are divided between Germany and Russia, then in 1942 the Germans invade and take Vilna and they seize the Jewish collections and begin to sort them.

Just behind the Blitzkrieg came an Operational Group, established by Alfred Rosenberg, the architect of Nazi Anti-Semitism, and run by a Nazi Librarian, Johannes Pohl, which was tasked with identifying books and documents to be sent back to Frankfurt, to Rosenberg's hideous ‘Institute for the study of the Jewish question’, with the rest of the material sent to local paper mills for destruction.

The Nazis forced the Jews of Vilna to live in the ghetto, and they chose a number of former librarians and archivists and other intellectuals to have the horrible task, at gunpoint, of sorting through these great Jewish libraries and archives, with their own history and culture, either for being sent to Germany, or to be destroyed. The Jews who were selected for this task became known as the ‘Paper Brigade’.

Here again we see the human impulse toward preservation, because the what the ‘Paper Brigade’ did was to smuggle items from the collections they were forced to sort through back into the ghetto every day, and they hid these books and documents inside the ghetto itself, in the hope that one day they could be recovered. Each time they did this they risked their own lives, displaying a compulsion to preserve their own culture, their own documentary witness to their community, to their civilisation, in the hope that they would endure, and the documents could speak to the lives they had before.

A few of the members of the Paper Brigade managed to escape when the Vilna ghetto was liquidated in 1944 and they came back after the Russians liberated Vilna and recovered some of the collections, actually tens of thousands of documents that they had managed to hide.

This effort to preserve the documentary heritage, the documentary witnesses of Jewish life would not just be happening in Vilna, it happened in other centres in Eastern Europe as well. In the Warsaw ghetto an archive was made by an organization called Oyneg Shabes, led by an extraordinary man called Erwin Ringleblum, who was murdered in the Holocaust, but he had managed to hide and bury documents which he and his fellow members had saved. These were dug up afterwards in metal cartons and milk canisters.

Some of the documents which had found their way to Rosenberg's Institute in Frankfurt were seized by American forces in 1945 and were sent to New York, where a branch of YIVO had been established. Here they are arriving in 1947 and the YIVO institute staff here are working through the packing cases, looking at the documents which have been somewhat perversely preserved by the Nazis but the other documents which have been sent to the paper mills by the Soviets.

Meanwhile, back in Vilna, the materials that had been saved by the ‘Paper Brigade’ and were sent for destruction again by the Soviets, and were actually saved once again, this time by a Lithuanian librarian called Antanas Ulpis.

Ulpis saved these documents by going to the paper mills and turning the trucks around and driving one of them back himself, and he hid them in a church that had been requisitioned as one of the storage sites for the new National Library of Lithuania. He squirreled these documents away in organ pipes in other locations and they only became revealed after Ulpis's death in 1989, as the iron curtain came down. They are now one of the great treasures of the National Library of Lithuania and are being digitized by the YIVO institute in New York.

I'd like to talk just very briefly about a more recent attack on knowledge and again one which really is in living memory, last year was the 25th anniversary of the Srebrenica massacre. The attacks on knowledge in Bosnia and Kosovo is another example of a cultural genocide that came before a human genocide.

The National Library of Bosnia and Herzegovina in Sarajevo was deliberately attacked by the Serb militia besieging the city with incendiary shells. No other buildings were targeted on this day, August the 25th 1992. The fire brigade and librarians that tried to rescue collections from the burning building were targeted by snipers. If you look at the western newspapers at the time you will find that the attack on the library, it didn't even get onto the front pages. The story was buried inside the papers and again it's the building that gets the focus, not actually the library itself, and the library is important because it's a symbol of the multicultural community that Sarajevo and Bosnia had managed to preserve with the written culture of Bosnian Muslims, Jews, and Christians all living more or less happily together, but something which the Serbs deliberately sought to eradicate the documentary and written evidence for.

It wasn't just the National Library that was targeted at the time. Provincial archives and land registries were also destroyed by Serbian forces trying to eliminate any record of Muslim land ownership.

A librarian called András Riedlmayer, who has just retired from the Fine Art Library in Harvard, collected evidence for UNESCO as to what had happened to libraries and archives in Bosnia. He even gave evidence at the International War Crimes Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia in The Hague for the trial of Slobodan Milošević and for other war criminals like Ratkan Mladic, and part of his testimony was both about the cultural importance of the National Library and also the lengths that were gone to by Serbs to destroy the knowledge that it contained.

I’m going to end by looking a little bit at digital destruction, and of course at the moment we're going through this kind of profound shift in the way that knowledge is both created and shared and stored and as a society we are kind of outsourcing the storage of social memory to the big technology companies. What the great Oxford historian, Timothy Garton Ash, calls the ‘private superpowers.’ What these companies advertise as free services aren't really free – we contribute our usage data, which is then harvested and mined for targeted commercial purposes. We also are seeing an increasing number of incidents of that ‘free’ storage being terminated as business models are reviewed and people losing access to collections which had been placed there. And of course, there are hostile attacks too, there's cyber warfare happening.

The preservation of knowledge is one of the pillars, I would argue, of an open society. But our reliance on the web as a platform for sharing knowledge and even for storing it, is very dangerous. We can see this when the Harvard Law Library did a survey a few years ago at the decisions of the Supreme Court in the United States at the website where all these decisions are now published and found in 2011 that 40% of the links on that website were broken that didn't lead you to anywhere. Access to the laws of the land is of fundamental importance to an open society.

Then in more recent times we've seen Cambridge Analytica, actually using the information that we all create every time that we search on a user search engine, use social media services such as Facebook, click ‘like’ on posts and so on, using it to influence these digital profiles of us, all of which are traded every day, to sell for influencing political agendas, and it’s the sort of data that was created by the advertising industry. One of the problems we face is that the tech companies do not have preservation in their business model. There is no Facebook archive: we do not know what the political adverts contained that were targeted at Facebook users during the 2016 Presidential elections, for instance. Some libraries and archives are now developing strategies to circumvent this. The National Library of New Zealand for example has a project where they are asking New Zealanders to donate the Facebook profiles, in order to gain a picture of how New Zealand society behaved with social media in the 21st century.

To give a further indication of the dangers that society faces with the tech industry, I would like to bring us back to the Mesopotamian interest in the prediction of the future. In fact, this is what the modern data-driven tech industry is all about – and it began with the ad-tech industry trying to predict your future spending habits. It then moved onto voting intentions and is now focussed on predicting your future health. I don't know whether any of you wear a Fitbit or use an apple watch to track your Digital health but of course what this data is doing is sending information about your health to these private tech companies. You can use it to monitor your vital health statistics, but it's being harvested and gathered by those companies now and it's helping them predict your future health. Google, for example, just purchased Fitbit, so they can easily match your search history – if you Googled the symptoms of heart disease, they can now match this with your biometric data from your Fitbit. How would you feel if they sold this information to your health insurer?

We can also see the power of the tech industry to suppress information that might be important for society to understand our contemporary world. In January this year we saw a group of insurgents, inspired by Donald Trump, storm the US Capitol building in Washington. Tragically, five people lost their lives that day. But we know that they used an encrypted messaging App called Parler to communicate and organise. Parler was quickly taken down from the App stores and from the web, but a not-for-profit library service called the Internet Archive preserved the Parler Website just before it disappeared, so we have a record of it.

Of course, President Trump was the first President to use social media to control political communications, and he did so incredibly successfully. But he also had a habit of deleting many messages shortly after sending them, not a high percentage but still of great significance, given how much he relied on Twitter as a platform. Several activist archivist groups set up systems to automatically screen shot each Tweet from Trump, and to make them publicly available as a complete record of his social media behaviour. The National Archives of the United States are now using this data on their own Presidential Library site for Trump!

The use of encrypted and self-deleting messaging systems is something I am now very concerned about, as they hide the communication between Government ministers, civil servants and special advisors on matters of great public concern, especially in the formulation of government policy, they should be handled under the 1958 Public Records Act, I have argued recently, and the Ministerial Code of Practice needs to be strengthened and parliamentary sanction given greater teeth to ensure we know what our paid officials are doing.

Why should we be concerned about attacks on knowledge? I’d like to leave you with this quote from George Orwell, written 70 years ago, but incredibly relevant for own era:

"The past was erased, the erasure was forgotten, the lie became truth."

© Professor Ovenden 2021

Part of:

This event was on Thu, 02 Dec 2021

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham College plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login