John Paul II as Philosopher

Share

- Details

- Text

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

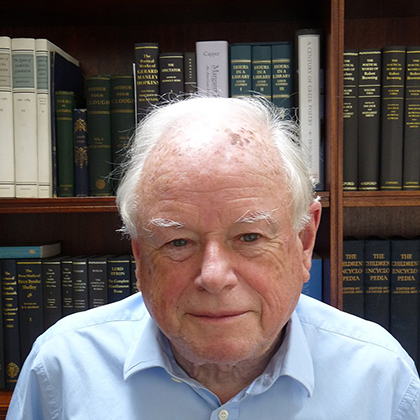

Dr Laurence Hemming, Heythrop College, University of London: John Paul II's call for a renewed Theology of Being: Just what did he mean, and how can we respond? Sir Anthony Kenny FBA, University of Oxford: John Paul as Thomist. Professor Wladyslaw Strozewski, Jagiellonian University, Krakow: Experience and Interpretation - Phenomenology and Scholasticism in Karol Wojtyla's thought. Professor Keith Ward DD FBA, University of Oxford and Gresham College: Veritas Splendor. Papers will be chaired by Dr Nicholas Bunnin, Forum for European Philosophy and Professor Gwen Griffith-Dickson, Director, The Lokahi Foundation and Fellow of Gresham College.

Download Text

Veritatis Splendor

Keith Ward

In 1993 John Paul II published an Encyclical letter on the subject of morality, Veritatis Splendor. It expressed much of his thinking on topics of moral theology, a subject in which he possessed scholarly expertise. It is a letter to the Bishops of the Roman Catholic Church, and so it may properly be taken as a definitive statement of current Catholic thinking on ethics. But it has a wider interest, since it claims to set out the correct account of what morality is, and to state a basic set of moral truths that hold for all human beings, whether Catholic or not. It also provides at least the sketch of a set of philosophical arguments in support of that claim.

It is as a piece of philosophical writing that I aim to discuss the Encyclical. My interest especially is to ask how much of it is meant to be established by purely philosophical methods - that is, arguments appealing to human reason without reference to divine revelation. In doing this, I will be concerned to draw attention to the points at which other ethicists would disagree with the positions taken, and to ask whether there is any rational method of resolving the disputes that arise. And I will seek to see how far the moral views of the Encyclical are distinctive of a Catholic view of divine revelation, and how far they might be expected to appeal to rational human agents in general, whatever their faith or lack of it.

1. In the Introduction to the document, John Paul sets out to address what he sees as a ‘genuine crisis’ in Catholic moral thinking. Some theologians, he says, are attacking the traditional Catholic view that the negative commandments of God can never be rejected in any circumstances. That is, there is a set of absolute prohibitions which must always be respected. These prohibitions belong to ‘natural law’, which is universal and permanently valid. Also, some theologians hold the view that a pluralism of moral opinions can be tolerated, being matters of subjective conscience. Thus they undermine the claim of the Magisterium, focused in the end on the person of the Pope, to define moral truths correctly and definitively.

The philosophical points at issue here can be identified as follows: first, is there a universal and immutable natural law? Second, does it issue a set of absolute prohibitions? And third, is there an area in which diversity of moral opinions, arrived at conscientiously, should be tolerated or is even inevitable? The question of the authority of the Pope to define moral truth is not one I propose to deal with, since it is based on the claim that Jesus gave authority to the successors of the Apostles to define moral truths. That is a matter of faith, and falls outside the purview of the philosopher. Obviously, if the Pope can, by the aid of the divine Spirit, define moral truths, that rules out all conflicting moral beliefs. But there is a more general question of how far moral beliefs can differ and still be tolerated, and of the degree of certainty with which moral truths can be known without the aid of revelation.

2. One of the most striking things about the Encyclical is its rejection of the view that salvation is confined to Catholics or, more widely, to Christians. ‘It is precisely on the path of the moral life that the way of salvation is open to all’, John Paul writes. Those who follow conscience, which is described as the will of God as it is known to them, can obtain eternal salvation.

Conscience is a preparation for the Gospel. It is obvious that consciences may err, but it is still right, subjectively, to follow conscience. The task of the Magisterium, he says, is to ‘deepen knowledge’ with regard to morality. It seems that natural morality may err, and that it can be deepened and perfected by revelation. We should therefore expect natural morality to be imperfect, liable to error, and capable of or even in need of development and correction by revelation. The relation between natural and revealed Christian morality will be one of ‘perfecting’, ‘development’, and ‘correction’. We should not expect too much of natural morality, then, but it is nevertheless an image in humans, however corrupted, of the divine law, and so at least lays the basis for fuller moral truth. The interesting question is exactly what this basis is, and that is the question I am addressing.

3.In the first chapter, John Paul begins with an elegant and profound sermon on Matthew 19, 16, the meeting of the rich young man with Jesus. Here John Paul outlines his view of what morality is at its heart and in its fulness. It is undoubtedly a view based fully on the revelation of God in Jesus Christ, rather than on a consideration of human desires and inclinations.

Morality, he writes, is an encounter with a reality of supreme goodness. Such an encounter takes place through meeting Christ, in the community of the Church. It arouses in the disciple a response of love, and leads to ‘a participation in the very life of God’, in supreme goodness itself. This is from beginning to end a work of divine grace, enabling humans to participate in the life of Christ. In the words of Aquinas, ‘The New Law is the grace of the Holy Spirit given through faith in Christ’.

This is a view of morality that could not be shared with atheists, with those who see morality as based simply on the reasonable realisation of human desires in a complex society, or on the extension of human sympathy and benevolence to others. It is morality as apprehension of, response to and participation in the Supreme Good.

Man’s final end is God, and to that all human life should be oriented. God, being supreme goodness, is absolute truth and beauty, and in Christian revelation God is known to be supremely compassionate and loving. So to participate in God is to participate in truth, beauty, wisdom, compassion and loving relationship with others.

There are here some fundamental moral goods, believed to be perfectly realised in God, and given to humans through Christ. How could a person who shares in the being of God not be committed to truth, beauty, the love of all creation, and in a special way the love of persons, who are created to share in the life of God?

On such a view, the basis for moral principles is the nature of God, the Supreme Good. That nature is revealed supremely in Christ, and is implanted in human lives by the Spirit. But what of those who do not believe there is a God? They will have to have a different basis for moral principles, and a crucial question is whether there is such a basis, one that could be universally accepted.

4. At this point John Paul refers to natural law, the law inscribed in the human heart, ‘the light of understanding infused in us by God, whereby we understand what must be done’. If there is a God, it is reasonable to think that there will be such a natural knowledge of right and wrong in all human beings. The traditional Catholic account of such natural moral knowledge is basically that of Aquinas, who says, following Aristotle, that ‘every agent acts on account of an end, and to be an end carries the meaning of to be good’ (ST 1a2ae, 94, 2). This seems to me an excellent definition of goodness, that does not rely on any theological beliefs. Whatever rational agents aim at is, for them, good. The ‘good’ is defined as whatever a rational agent aims at. But on this definition there is an indefinitely large number of goods, of objects of reasonable desire, and they may differ enormously.

A ‘moral good’ might be defined as an object of reasonable desire at which all rational agents would aim, and Aristotle has that in mind in his discussion. Are there states at which all rational agents would aim? It seems plausible to say that pleasure would be chosen over pain, knowledge over ignorance, beauty over ugliness, and freedom over slavery. These are goods which all have reason to choose, and if they are good for one rational agent, they are good for any other agent of the same sort. Reason can, then, discern some universal moral goods.

But such objects of universal rational choice are very general, and they allow of many differences over what gives pleasure (push-pin or poetry?), or what sort of knowledge to obtain (just enough to avoid disaster, or understanding for its own sake?), or what is thought beautiful (Mozart or the Sex Pistols?). Universal agreement only exists at a general level, and allows a wide plurality of choices of more particular goods, many of which may be conflicting.

It is easier to identify universal evils, like extreme pain, being deceived, losing valued possessions and being enslaved. These are universal, in that no rational person would wish to experience them. While there may be many disagreements about what is good, there would be more agreement about what is evil and undesirable. This generates a form of natural moral knowledge. Humans can know, in general, what sorts of things are right and wrong - acts leading to universally desirable or undesirable states.

In this way, we might expect all humans to accept, without any appeal to God or revelation, something like the ‘Golden Rule’ in its negative form - do not do to others what you would not want done to you. That will generate moral prohibitions like not killing, stealing, deceiving or destroying friendships and marriage relationships - prohibitions which are found in the Ten Commandments.

Of course, knowing that these things are bad in general is purely hypothetical knowledge. I might say, ‘If I were perfectly rational and dispassionate - an impartial observer of the human scene - I would agree that such conduct is prohibited. But I am not such a dispassionate observer. So why should such prohibitions apply to me, a passionate animal who reasonably seeks my own good and that of those I love, above that of others?’

Why adopt a universal morality, even if I do know what in general it would be? It is at this point that it makes sense to speak of a ‘fundamental option for (or against) the good’. That is the path of the moral life which is a preparation for the Gospel. Whatever their beliefs, humans have enough knowledge of what is right and wrong to decide for or against the good. But without revelation they do not know the nature of the Good in more detail. That is why there is a place for revelation in morality. Nevertheless the Ten Commandments were not needed to tell people what was in general right and wrong. They were needed to make the commands categorically obligatory.

The natural knowledge of right and wrong does not of itself generate absolute moral prohibitions. I may not wish to be deceived, in general, but I may want to be flattered on occasion, and I certainly do not always want people to tell me the blunt truth. There may be many occasions on which I do not mind being deceived for a good reason (for instance, when a big surprise party is being planned for me). So I can rationally break the precept not to lie to others, if that sort of reason can be produced. And the same holds for taking human life. There may be occasions on which I would no longer desire life, even though I agree that life is good in general. Then the Golden Rule would permit me to take the lives of others when they desire to die. There may be other prudential reasons why I should not have such permission. But at least the arguments would have to be taken seriously. Appeal to universal knowledge of right and wrong seems to lead to prima facie prohibitions. A prima facie prohibition is one that holds unless there is some other moral principle with which it conflicts. Then one of the prohibitions in question is over-ridden. One would expect the prohibition on taking life to outweigh the prohibition on lying. But it may be impossible to state rules about weighing moral judgments that will hold in every possible circumstance. In this way, natural moral knowledge is unlikely to lead to absolute prohibitions.

5. Aquinas’ version of natural law does not just hold that there is a natural knowledge of right and wrong. It also holds that the goods that are ‘natural’ are those ‘towards which man has a natural tendency’ or natural inclination (naturalem inclinationem). The criterion of universal desirability is logically distinct from the criterion of natural inclination. I may have a natural inclination to do undesirable things. In fact I probably do, if I have a natural tendency to kill my rivals. I may also desire to do things for which there is no natural inclination. Again, many people do, for some desire to change their bodies by plastic surgery, even to grow facial whiskers like cats. There is no natural tendency to do that.

I may have an instinctive, or natural, tendency to run from wild animals. But perhaps I should counteract that tendency, to become more courageous or in order to make friends with animals. As G. E. Moore argued, one cannot assume that a way in which I naturally tend to behave is desirable, either for myself or for others. Humans tend to rape, kill and lie, and such behaviour is very undesirable.

The view that natural inclinations are, as such, good would be widely denied by evolutionary biologists. We now know, though we have only really known since 1953, when the structure of DNA was discovered, that there are behavioural tendencies in human beings that are laid down in the coding of transmitted DNA. It is our DNA that carries a code for building proteins that will in turn construct bodies with specific physical characteristics and tendencies to behave in certain ‘instinctive’ ways. These are our natural inclinations.

In every generation DNA is subject to mutations or chemical changes - humans generate about 100 mutations per generation. Most of these are harmful, and so are anything but good. Some of them give rise to natural inclinations that may or may not be harmful. Most of the harmful inclinations are eliminated by natural selection, but some get through. So the tendency to hate foreigners, and for men to subjugate and rape women, are tendencies that have proved quite conducive to human survival as a species. But they could hardly be called good, or in accord with the purposes of God.

It is, of course, true that the things we naturally tend to do have been conducive to survival over thousands or millions of years. Otherwise we would not have survived. And it seems likely that behavioural tendencies conducive to survival would have come to be thought desirable, and to be associated with pleasure.

But these are not necessary or inviolable connections. I may have a tendency to take intoxicating substances, which give pleasure. Such a tendency may be genetically ingrained, and it may have survived in the genome simply because its harmfulness has not been bad enough to wipe the human species out. Nevertheless, intoxicating substances may be very bad for me, and kill me in the end. From an evolutionary point of view, this would not matter very much, since in the end I would be beyond reproductive age in any case, so the harm done to me would not cause any decrease in fecundity. It might even increase my fecundity when I am young, though it will kill me as soon as I am past child-bearing age. So this natural tendency will be good for reproductive success, but bad for me personally. If I can take rational control of my behaviour, I might well desire to live longer and reproduce less, in which case my rational desires will conflict with my natural inclinations. To take another case, humans may be naturally aggressive, for that has had an evolutionary advantage in the past. But now it is counter-productive, and may lead to the extermination of the human race. What is genetically programmed, according to evolutionary biologists, is what was good for the survival of my genes in the far past, or what at least was not counter-productive, thousands or millions of years ago. That may now be very bad for survival, and so should be rationally opposed.

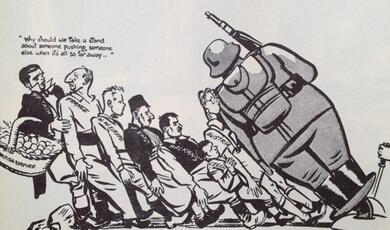

The evolutionary theorist Richard Dawkins speaks of the possibility of rebellion ‘against the tyranny of the selfish replicators’. On most evolutionary accounts, my inherited tendencies need to be rationally controlled or even opposed. As Tennyson wrote, ‘Nature is red in tooth and claw’. T. H. Huxley, in a famous essay on evolution and ethics, held that evolutionary success depends on increasing lust and aggression and on the ruthless extermination of rivals. The behaviour this naturally gives rise to is a strong sense of kin-group, limited altruism, coupled with extreme hostility to all competing groups. In the modern world we may need to counter these natural tendencies, extend human sympathy more widely, and encourage rational control of instinctive behaviour. Reason can often find itself in opposition to natural tendencies or inclinations. An evolutionary account of human behaviour shows how this can be so - because what proved advantageous in the far past may be fatal now.

6. When he considers natural inclinations, Aquinas outlines three main types of natural inclination - one shared with all substances, namely, the appetite to self-preservation. The second is what humans share with animals - sexual intercourse and the bringing up of the young. The third is inclinations of beings of a rational nature - including knowledge of God and what relates to living in society (friendship and so on).

Natural law covers ‘everything to which man is set by his very nature (94, 3). In an evolutionary worldview, we do not have to reject this principle. Human nature is purposively intended by God, and the inclinations Aquinas picks out - to survive, procreate, know and appreciate beauty and truth, and share friendship and love with others - are inclinations that seem necessary to realising the divine purpose. But we have to say, more clearly than Aquinas did, that nature itself has no purposes, and not all her tendencies are good. God has purposes, to be worked out in and through nature. They can indeed by discerned by reflection on nature, but only by discriminating what tends to the flourishing of personal life from what tends to frustrate such flourishing. An inspection of natural processes themselves will not enable such a discrimination to be made.

For Aquinas the precepts of natural law will be very general, since they cover what is common to all human beings as such. With regard to such general principles, ‘What is true or right is the same for all and is equally recognized’ (94, 4). But ‘with respect to particular conclusions come to by the practical reason there is no general unanimity’. Aquinas does not think that such matters are indifferent or relative - that there might really be different conclusions that are equally right or permissible, that what is right is not always the same for all. But he supposes that people may reasonably derive different particular conclusions from general principles, even though some of them will be mistaken.

Not only are mistakes possible in formulating more detailed precepts. General rules also admit of exceptions in particular cases. In the example Aquinas takes, natural law can tell you that it is right to return goods held in trust to their owners. But by itself the law cannot tell you in specific cases, where special conditions may obtain (the owner may be about to use the goods to attack one’s country) whether it is right to return goods or not (94, 4). ‘The general law admits of exceptions’ under special conditions. This is most obviously so when divine commands over-ride natural law (as when God commanded Abraham to sacrifice his son). But it may also be so ‘on some particular and rare occasions’. In the instance cited, the law against theft is over-ridden by a precept to prevent loss of life. In a similar way, many hold that the law against lying can be over-ridden by the precept to prevent murder. Though later moral theologians did not allow such exceptions, Aquinas himself plainly did.

7. Theists, I have suggested, are bound to interpret nature in a purposive sense. But if strongly influenced by evolutionary theory, in a broadly Darwinian sense, they would not regard physical processes as of value in other than an instrumental sense. Such processes and tendencies would be good only to the extent that they subserve the purpose of enabling personal life to flourish.

This is precisely one of the things John Paul complains about in the writings of some Catholic moral theologians. He is especially critical of any attempt to split personal life from biological life in the human person. One of the major arguments of the Encyclical concerns what John Paul calls the unity, integrity and dignity of the human person.

Modern biologists would have a great deal of trouble in using the Aristotelian theory, since it is for them suspiciously close to ‘vitalism’, the discounted theory that there is a life-force or vivifying principle that accounts for organic life. But they would have sympathy with the view that humans are psycho-physical unities. There is almost unanimous rejection of what they call ‘Cartesian dualism’, the idea that the soul is a spiritual substance, only contingently associated with the physical body.

One way of putting the most widely held modern view is to say that humans are physical bodies, animals, that possess emergent properties of consciousness and volition. To speak of a ‘soul’ is to speak of the capacities of a type of physical body, capacities of a type of animal capable of abstract thought and responsible action. Souls cannot properly exist without bodies - a view Aquinas espoused.

The complication here is that the soul is often spoken of as though it is a non-physical agent of thought, action, sensation and perception. Some form of embodiment may be essential to it, in order to provide information, and the possibility of communication and action. But perhaps the same soul could be embodied in different forms. Anyone who believes in rebirth must believe this. Catholics, who do not share that belief, do nevertheless seem to be committed to the existence of souls, both in Purgatory and in Heaven, that have consciousness and experience, but do not have physical bodies. Moreover, whatever the resurrection body is, it is certainly not temporally or physically continuous with this physical body, and it may be significantly different in some respects (it will not be corruptible, and will not have exactly the same physical properties as the physical body when it died).

Aquinas said that unembodied souls exist ‘improperly and unnaturally’, by the grace of God, and will not fully be persons again until the resurrection. But it is obvious that a resurrected body will not be constituted of the same physical stuff as present bodies (it is said to be spiritual, not physical). The present physical universe will come to an end, and there will be ‘a new heaven and earth’. What that means is that the physical stuff of this specific universe is not essential to the nature and continuous existence of persons, even though something analogous to this body must exist.

What is at stake in this discussion is whether human consciousness is an emergent property of a physical object - and so ceases to function or exist without that object. Or whether human consciousness, though it does originate within a physical body, and does require some form of embodiment, is nevertheless dissociable from its original body, and is capable of existence in other forms. Is the soul adjectival to the body, or is this body just one form in which this soul may exist? Aquinas tries to straddle both sides of this divide by speaking of the soul as a ‘substantive form’, something whose function it is to give a body specific capacities, but which is capable of existing, though not of functioning in its full and proper way, without that body.

It is this point that many biologists and psychologists have great difficulty understanding. Many of them can see intelligence as an emergent property of a physical organism. But they are resolutely opposed to any form of vitalism, of a view that the body is actually regulated in its physical organisation and structure by a spiritual principle or agency, whether this is called a ‘soul’ or a ‘form’. This may seem a rather recondite philosophical dispute, but actually it shows the importance of views of human nature to morality. Our view of what a person is may make a very important difference to the moral precepts we accept.

8. John Paul is especially concerned to say that the body should not be regarded as simply ‘raw material’, something ‘extrinsic to the person’, that can be shaped or dealt with in any way one wishes. The unity of soul and body means that we must respect our bodily structure, since that is part of what we essentially are - ‘body and soul are inseparable’, and the body intrinsically has moral meaning. We might contrast this view with some Hindu views that the body is just a garment that we put on or off. For John Paul, the body is constitutive of what we are, and we would not be the same being without it, without the specific body we have. This is what is intended by the traditional Catholic view that each soul is fitted for a specific body. We might say that each soul is the unique soul of a unique body.

From this two things are said to follow. First, the finality of our bodily tendencies cannot be regarded as purely physical or pre-moral. It is morally relevant, and relates directly to the fulfilment of the total human person, body and soul. Second, each person, as created in the image of God and ordered towards participation in the life of God, has intrinsic dignity and inviolability. Some acts are intrinsically incapable of being ordered to God. They contradict the good of the whole person. These are acts identifiable as hostile to life, to the integrity of the person (torture or bodily mutilation), and to human dignity (slavery, punishment without trial, and degrading work).

The first question that must be posed by the relentlessly critical philosopher is whether this view of the person is knowable by natural reason. It seems not. For philosophical accounts of human personhood range from the reductive physicalism of Alonso Church (who denies that consciousness is important or even existent) to the pure idealism of Timothy Sprigge (who thinks that bodies are illusory appearances of pure mental realities). These are philosophers trying to give a reasoned account of human persons, and they disagree as much as they possibly could. My conclusion is not that the Catholic view is wrong. But it cannot be established with any certainty by reason. It can be reasonably maintained, and of course it can be accepted as true. But it cannot be defended as an account that all reasonable people can see to be true. To that extent, it cannot be the basis of a morality that all can accept with a reasonable degree of certainty. Catholic morality will depend upon a Catholic view of persons. That view of persons may be true, and it should certainly be defended by Catholics. But it will generate a distinctively Catholic view of moral precepts that is unlikely to be shared by all rational agents.

At least we can locate where these disagreements begin to arise. And one place is belief in persons as physical organisms with intellectual or spiritual capacities. These capacities are rooted in a non-physical entity, capable of non-physical existence, but the proper functioning of which is within the specific physical body which is part of its proper being, and which has always to some degree limited and shaped its operation.

What follows from this account? Certainly, that human bodies are not mere adjuncts of persons. When they are functioning properly, they should express a personal life. Bodily acts are personal acts. Part of human flourishing is bodily flourishing, and that means due realisation of the capacities and excellences of the body. The most basic moral principle this suggests is that of life and health. The body should not be abused. So while there is nothing wrong with eating for pleasure, the real purpose of eating is to produce a healthy body, and considerations of pleasure should be subordinate to that. The use of drugs and excessive wine or food is morally prohibited, and regular exercise is morally prescribed.

It is not so clear, however, that such prohibitions allow of no exceptions. Excessive drinking is incapable of ordering a life towards God, and it contradicts the good of the person. But does this entail that there are no circumstances in which one may get drunk? Suppose that some madman threatens to shoot your family unless you drink a bottle of whisky. Would it not be right to drink the bottle? Such an act might reasonably be seen as violating the dignity of one’s own person. It would hardly be worth formulating a moral principle: ‘Never get drunk unless a madman threatens your family unless you do’. It would not undermine the importance of the principle of temperance to accept such hopefully rare and extreme cases. One would simply be saying that preventing the death of many innocent people is more morally important than not getting drunk. The fundamental point would be that moral precepts can, in rare and extreme situations, conflict. When they do, they can be ranked in order of moral importance, and the less important precept can be violated if it is the only way to keep the more important precept.

Moral prohibitions can be serious without being absolute. And if one accepts that there are degrees of moral importance, and that precepts can conflict, then it seems reasonable, without benefit of revelation, to think that some prohibitions can sometimes be violated.

9. I began by asking whether, without any appeal to revelation, there are universal principles of natural morality. My view is that such universal principles, prohibiting conduct that leads to rationally undesirable states, can be found. But such principles will be very general, and they may not carry the force of obligation - something more is required for that, and the existence of a morally commanding God is one way of providing it.

However the attempt to base such general moral precepts on genetically determined behaviour patterns - on what Aquinas called ‘natural inclinations’ - is largely undermined by Darwinian views of evolution. For such views, nature has no purposes, and the purposes of God in nature are attained through processes of random mutation and natural selection. If we can make mutations less random or selection less morally neutral, that seems to be a good thing. To that extent, it is no longer compelling to say, with Augustine, that God ‘commands us to respect the natural order and forbids us to disturb it’, or that all things have a natural inclination to their proper act and end.

Natural reason would also be unlikely to think that basic moral prohibitions are absolute, in allowing no exceptions under any circumstances. John Paul writes, ‘Only a morality which acknowledges certain norms as valid always and without exception for everyone, can guarantee the ethical foundation of social coexistence’ (97). I have to say that is simply not the case. There can be strong foundations for social morality in a set of prima facie moral precepts, that all can see to be right in general, though conflicts are possible between such precepts. So ethical decisions are often difficult and agonising, precisely because we have to weigh different sets of moral considerations. It is quite possible to insist on the moral importance of precepts like not killing, lying or stealing, without adding that such precepts can never conflict or be over-ridden in extreme cases by stronger precepts.

We may agree that ‘without intrinsically evil acts, it is impossible to have an objective moral order’ (82), but add quite consistently that there can be degrees of wrongness (lying is less grave than killing), and that there are genuine moral dilemmas, when intrinsically evil acts conflict. It then becomes obligatory to do the lesser wrong. We would of course have to interpret the word ‘intrinsic’ as meaning ‘wrong in itself, not just because of its consequences, except in cases where it is over-ridden by a greater wrong’. This might be called a weak interpretation of the term ‘intrinsic’. But that is an intelligible interpretation, though it is not the same as the strong interpretation of intrinsic, namely, ‘Without any exceptions at all’. It is precisely because there is an objective moral order that we can assess the relative gravity of various moral prohibitions, and determine never to violate a moral prohibition except in cases where it is over-ridden by a stronger prohibition.

10. Though it is often quoted, Paul’s question, ‘Why not say...let us do evil so that good may come?’ (Romans 3, 8) is not appropriate to such situations. He is thinking of people who sin intentionally in the belief that God will forgive them. But even if it is taken in a broader sense, to forbid doing an evil act in order to bring about good, it still does not apply to situations in which two moral precepts conflict. We are not considering killing somebody that everybody else hates, in order to make everybody else happier. We are only considering doing the lesser of two evils, where there is no escape from the dilemma. It is true that this makes moral decision-making less clear and more complex. But for many people that is what morality is, an objective moral order that is very difficult to discern in particular cases.

This discussion should make it clear that there are conscientious moral differences between rational agents that seem to be rationally unresolvable. The questions of whether human life begins at conception or at some later stage in embryonic development, of whether homosexual activity is intrinsically disordered, and of whether there are absolute moral prohibitions, are such that there is no agreed way of resolving them. That certainly does not mean that all views are equally correct. But among reasonable views there remain unresolvable differences. This perhaps is one reason why a Catholic may in the end appeal to the Magisterium for a correct view.

It follows that, as far as natural morality goes, there can be certainty with regard to general moral principles, but no rational certainty with regard to many particular moral issues. It is at this point that Christians may point to the distinctive character of Christian morality, as rooted in encounter with Supreme Goodness. And Catholic Christians may point to their distinctive belief in the Magisterial authority of the Roman Catholic Church in matters of morals.

Natural morality does provide a firm basis for fundamental moral knowledge. But it lacks a firm basis for the sense of categorical obligation that belongs to fundamental moral precepts. And it lacks the sense of a Supreme Good that attracts our love and offers us a share in its perfection. Secular morality may not even want or feel that it needs such things. But I think John Paul is right in holding that personal response to a sense of obligation is a preparation for that conscious response to God that brings salvation. It is already a sort of moral faith, though it is imperfect and uncertain.

I also respond warmly to his insistence that human freedom should be always in the service of truth, and that the exercise of freedom without a search for objective moral truth is a path to possible disaster.

But I remain unconvinced that the desire to love and obey God entails commitment to absolute moral prohibitions. One can believe in the unity, integrity and dignity of the human person, without thinking that there exist any specific ‘finalities’ or purposes in the physical and genetic processes of nature, and without thinking that there are no circumstances in which genuine moral dilemmas can arise that may give us reason to make exceptions to general moral prohibitions.

More strongly, I think a perception of the spiritual destiny of humanity suggests that the physical body does not have morally absolute status, and that the primary spiritual principle, besides the love of God, is the flourishing of personal life rather than the preservation of the present physical order, whatever it may be. The physical order may need to be ordered to the greater flourishing of sentient, intelligent and responsible life, before it fulfils what we might see to be its proper role.

So I think that acceptance of a moral Magisterium is necessary for commitment to the specific moral views that this Encyclical emphasises and defends. An insistence on inviolable moral precepts and intrinsic evils, in a strong sense, depends not on purely natural reason, nor on seeing morality as a loving response to the supreme goodness of God, but on the teaching of the Pope, guided by the Holy Spirit. I have no philosophical objection to that. My only point has been to try to get clear about what a natural, non-revealed, morality might be, and how far and in what ways Christian revelation may add to such a view of morality. To answer such questions, study of Veritatis Splendor is a valuable resource, which helps to make clear both the distinctiveness of Roman Catholic morality and the general relation between morality and religious faith.

© Professor Keith Ward, Gresham College, 16 November 2006

Experience and Interpretation Władysław Stróżewski

Institute of Philosophy, Jagiellonian University

This lecture aims at attempting to explain the relation between experience and interpretation in the philosophical practice of Karol Wojtyła. The assumption that must be made at the beginning – in accordance, in my opinion, with the thought of the philosopher in question – is that experience calls for interpretation; this is indispensable if experience is not to consist only in the registration of data, or in the completion of a set of more or less organised facts, but it is to be the basis for a specific body of knowledge – scientific or philosophical. The notion of "experience" is not unambiguous. The ways of using it in different situations proves this. Thus, we speak of experience meaning a single, direct encounter with some reality (e.g. " the experience of an adventure" or "the experience of a tormenting pain"), but also when we take into consideration a long-lasting relationship with some person, object or process (e.g. "the experience of someone's character", "the experience of an illness "). "Experience" can be related to accidental facts, but it can also mean activities carried out in a specific manner and planned in advance (e.g. a laboratory experiment). It is used for single facts, especially outstanding in one's life (e.g. "the experienced a great injustice"), and for the cumulated experience of facts, which justifies speaking about, "the experience of life", for example. All of these meanings – and the above list is not exhaustive – have played a specific role in the crystallisation of various philosophical concepts of experience. There are many such concepts, and they vary not only due to significant differences that exist between particular kinds or types of experience, but also depending on the assumptions of the theory or – in a wider sense – of the philosophical orientation which defines them. To learn about it just focus one’s attention on understanding "experience" in Neopositivism, on the one hand, and in phenomenology, on the other. From the point of view of our considerations, it is sufficient to mention three concepts of experience which played a special role in the history of philosophy: empiricist, mystical and phenomenological. This simple list should not be treated as a classification or typology of experience. 1. Experience in the empiricist sense is limited to a direct contact of the sensory powers of the learning subject with an object adequate for such powers. If the only source of knowledge is experience understood in this way and its fragmentary data is the only object of knowledge, we have extreme empiricism, which ultimately turns into sensualism and phenomenalism. 2. The second understanding of experience we are interested in, comes from mysticism. Here it means a direct contact of the subject with what is radically hypersensual and transcendent, not only with respect to the sensual cognitive dispositions of a human being, but also with respect to those which relate to the discursive powers (intellect, reason). Mystical experience is personal and subjective, but it is characterised by absolute certainty and the deepest conviction of the veracity of the data acquired there and, as a consequence, of the statements which will be formulated on the basis of them. "I shall speak of nothing of which I have no experience" – wrote saint Teresa of Avila, in writings in which "experience" is a key word: P. Blanchard says that it appears there 168 times![1] Mystical experience, characterised by a special dynamics of the way travelled in it, culminates in a state which is described as a soul's unification with God. "This participation comes not only morally, but also physically, into concrete human resource as a dynamic element. These dynamics go, as is clearly apparent from the described experience and the lecturing of St. John of the Cross, in two directions: in the direction of its proper Object, which means in other words: it opens man to God, it makes the connection with the very Divine Being available to him – and at the same time it goes in the direction of the subject; in the subject it carries out some real metamorphosis, change or transformation"[2]. 3. We owe the third concept of experience to phenomenology. It retains some postulates of empiricism, especially the postulate of directness, radicalism, and "purity" of cognition ("empirical naturalism originates – writes Husserl – from motives worthy of respect to the highest degree"[3]). However, it rejects the limitation of the sources of knowledge to sensual experience alone. At the same time it formulates new conditions, the fulfilment of which is decisive for a proper understanding of experience. "Direct 'seeing', not only sensual, experiencing seeing, but seeing as such, as source-presenting awareness – no matter of what type – is an ultimate source of justification of all reasonable statements. It possesses the justifying function only because and only to the degree to which it is source-presenting"[4] "Thus, we present something more general as experience – "evidence" – and in this way we reject identifying science as such with experimental science".[5] In this way new fields of direct experience, or – more precisely – evidence, are opened. Eexperiences of which one is now aware, someone else's physical states, works of art, values, ideas can enter its range as the individuality of their mode of experience allows. For the same reason a reliable and serious treatment of mystical experiences applies. It is important, however, to be aware every time not only of what, but also of how something is presented to us. "It is necessary – says R. Ingarden – in all spheres of objects – whatever they are – to <<experience>>, i.e. to reach the direct data of examined objects and surrender to them, that is, to present them in such a way and within the same limits in which these data by themselves aspire to that."[6] In this way these data are "purified" from what is alien to them, and this "…means a return to the natural abundance of things and particular processes".[7] In the philosophical work of Karol Wojtyła the last two of the aforementioned concepts of experience play a special role, and mystical experience was present rather as a subject of examination, while experience in the phenomenological sense became a basic part of the method he applied. Mystical experience was thoroughly analysed during his research on the mysticism of St. John of the Cross. This research had a double significance. Firstly, it brought a deeper understanding of the phenomenon of mysticism, secondly, it resulted in noticing the possibility of broadening the notion of experience to other spheres of experience, especially that of moral experience, and mostly the specification of the concept of human experience, which now became a point of reference for all possible detailed experiences. Let us add here that the notion of "human experience" is one of key notions in the philosophy of Karol Wojtyła. According to the methodological postulates of phenomenology, experience requires an adequate, complete and detailed description of the data available to us. Language is a tool for description, so that it must be subjected to successive requirements. And the point is also that one's own experience, sometimes difficult to explain, is to be presented to to others, and intersubjectivity of the cognitive results obtained in phenomenological experience is to be obtained. Different types of experience require different types of language. Phenomenology prefers colloquial language, understandable by the majority of people, but rich and "flexible". "For this reason – says R. Ingarden – we choose words that are as intuitive as possible, i.e. having the capability of bringing before our eyes adequate objects. For this purpose words taken not from books but from everyday life are the most suitable, the words which have not lost their distinctiveness, or even their maturity, in the usage of a pure theorist, the words which would show us objects rather than specify them in an abstract way (even if very precisely)".[8] Karol Wojtyła is fully aware of these postulates; what is more, in some respects he goes even further. Thus, when he writes about the linguistic expressions in which the mystical experience is described by St. John of the Cross, he makes a significant remark: "Poetry undoubtedly facilitates a lot for the author in this area, which cannot be expressed equally either within colloquial prosaic language or in the bounds of strictly scientific terminology "[9]. I quote this opinion, as – in my opinion – it also sheds light on the place which his own poetry occupies in John Paul II's work: is it not a special way of communicating about experiences which it would not be possible to express in a different language? Was it not the special "how" of these experiences which caused the need to present their contents in a form which, even if not totally poetic, is close to poetic form? The area of experiences that refer to objects which in their essence are saturated with values and of necessity deeply move the subject which experiences them, requires a different type of "officially describing sentences" than experience leading to the discovery of pure sensual qualities or abstract ideas. This is worth remembering when we speak about the integrity of human experience and the adequateness of its expression. Each description is – at least to some degree – an interpretation of what is described. What, then, is interpretation? We reach the second part of the title of our lecture, equally ambiguous as the first. Most often interpretation is understood as "scientific activity aiming at the disclosure and explanation of the sense (identity, functionality, role, etc.) of a given phenomenon, especially through the definition of the place of this phenomenon in some whole of a higher degree. The starting point for all interpretations is the assumption that the essential meaning of a given object is hidden behind the data from a direct empirical observation and cannot be indirectly taken from it"[10]. Such a concept of interpretation is closely connected with the concept of understanding that can be defined as the "cognitive defining of something in an essentially indirect way", while “it takes place when 1. we encounter directly something which takes us cognitively beyond itself, indicates something else, refers to it or suggests it or forces us to look for something more through itself, and when 2. following these indications or suggestions we discover something new in relation to what was explicitly indirectly available to us”.[11] When we look at the meaning of the word "interpretation", we can discover one more aspect of it. First of all, let us notice that it consists of "inter" – which means "between" and the part coming from "pretium", which means: price, worth, payment, reward. Thus, interpretation can be understood as not only discovering the unknown through the well-known (especially through the analysis of the well-known), but also as a special "comparison" of one with the other, or better: judging one by or through the other. Interpretation understood in this way means a kind of "translating" of one value into another, usually carried out from a specific point of view and according to criteria accepted in advance. It is the interpreter's task to define these criteria and to be faithful to them. In this way a value that was not noticed at first can be discovered; in the course of interpretation it is disclosed to such a degree that its equivalent in a different system of values is shown. "Above all, hermeneutics (i.e. the art of interpretation – W.S.) must be shown as what restores sense as its renovation" – wrote P. Ricoeur.[12] To restore sense means not only to discover it, but also to show its value, which was unknown up to that time, to bring it back or perhaps even to attribute value to it again. This will only be possible when the appropriate point of view is found, which will really allow it. In the works of Karol Wojtyła we can find examples of using both interpretations: as "understanding" (or "deepening") and as "restoring". Certainly we could investigate their further, detailed varieties. For the time being, let this statement suffice as a starting point for the investigations specified by the subject of our lecture.

2. The experience of manThe starting concept of The Acting Person is the experience of man. This concept, as well as the scientific postulates connected with it, does not appear here for the first time. "The principle of insight and experience is found at the very basis of all humanism" – wrote K. Wojtyła in the already quoted, relatively early essay On the humanism of St. John of the Cross.[13] The Acting Person is a continuation of the programme started there, which will now be consistently carried out on the basis of original analyses of the fact that "human beings act" and take responsibility for their actions. Human experience is a special experience: 1º it is characterised by some features which cannot be attributed to any other experience, 2º it cannot be reduced to any other experiences. It could be described as starting a cognitive contact with one's own mental life; this cognitive contact takes place in different ways and includes multifarious data. Let us attempt to characterize human experience in the several aspects which are included by Wojtyła in The Acting Person. Thus: 1. From the side of the subject this experience is first of all the experience of oneself; however, it also includes the experience of another human being. This broadening of the range will turn out to be extremely important: the full integral content of the concept of human experience is necessarily also constituted by the experience of another. The thought of Wojtyła can, then, be formulated the following way: speaking about human experience I mean not only one individual subject, even if this subject be me. I, as subject and object at the same time, am available to myself in an especially distinctive way, but human experience is not limited and cannot be limited to me. Its range must, then, be broadened by the experience of another person, and this way of experiencing cannot be omitted, since a human being as such is to be the subject of research. Something that Wojtyła calls the "generic stabilisation of the subject" takes place here. To conclude: if the subjective side of human experience is to be fully reconstructed, one has to say that it includes three, ontologically incommensurable elements: me and not-me, understood as particular individuals, and "human being as such", i.e. the generic content, constituting itself on the basis of these individual experiences. 2. Broadening the range of man's experience also has an effect on the direction of this experience. This can be either internal or external. These terms must be defined, as they can mean – correlatively – either psychical - physical (corporeal in particular), or subjective – objective. Having the first pair of meanings in mind, I can confirm that the experience of myself can be either internal – i.e. when I direct myself to my psychic states, acts that I perform as a conscious subject etc., as well as external – when my body becomes the object of my attention. The same is true when it is about the experience of another human being: it does not solely come down to grasping the things that are external and corporeal in a human being, but in general it also puts me in human cognitive contact with his/her interior. In the second sense, internal experience broadens in range onto the whole of my psychical and physical states, while external experience is related to the whole objective sphere extending beyond my own self, in the broad sense of this word. Taking into consideration internally and externally directed human experience understood in this way, it must be stressed that these "directions" never occur in total isolation; on the contrary, one as it were presupposes the other and one enriches the other. "Man never experiences anything external without having at the same time the experience of himself"[14] – we read at the very beginning of The Acting Person. On the other hand, experiencing one's own self, man cannot take into consideration the knowledge he acquired from his contact with other people: this knowledge enriches the experience of this self even by the fact that it serves as material for comparison or justification, in the form, for example, of specific questions which could be directed towards one's own self. "Other human beings in relation to myself are but the ‘outerness,’ which means that they are in opposition to my ‘innerness’; in the totality of cognition these aspects complement and compensate each other, while experience itself in both its inner and outer forms tends to strengthen and not to weaken this complementary and compensating effect".[15] 3. The structure of human experience necessarily also requires characteristics of two types. First of all, it can be simple or complex, secondly, identical or differentiated. The first pair of notions does not require further explanation; it must only be said that – according to Wojtyła – some human experience is in its essence the outcome of numerous particular experiences, (including internal and external experiences). It is, thus, a unity resulting from many different factors. "We may even say that the complexity of the experience of man is dominated by its intrinsic simplicity".[16] The identity and differentiation, and more precisely, the disproportion of human experience is most closely connected with the concept of the object and the range of such experience. So, it turns out that in spite of different objective perspectives, human experience is something identical in itself and, as such, it transcends each particular way of experiencing. The object of the "identical" perspective is the human being in his – as Wojtyła expresses it – generic "stabilisation". A far-reaching share of intellectual cognition is required to shape acts of experience (which are actually never devoid of this intellectual element). But due to the fact that it is obtained, it allows mutual interpretation of different, incommensurable particular experiences, and it is "…a basis for developing our knowledge of man from what is supplied in both the experience of the man I am and of any other man who is not myself".[17] 4. The last aspect of the characteristics of experience in question remains, namely the way in which it takes place. Once again the moment of exteriority and interiority returns here: both directions of experience necessarily lead to different ways in which it takes place. Both external and internal experience can be indirect or direct; however, in each – even in purely sensual direct cognition – intellectual cognition is included, and it brings about the possibility of understanding this experience. Human experience is, thus, always integral; the phenomenalistic notion that separates the purely sensual level from the intellectual level does not hold up to criticism. "Thus in every human experience there is also a certain measure of understanding of what is experienced".[18] This thesis is of great importance. Being in concordance with the basic theses of phenomenology, which emphasise the unity of acts of human cognition, it allows for an integral approach to its object, the human being, and all facts which are in any way related to him.

3. Experience of the fact that man actsThe object of analyses carried out in the book The Acting Person is not the whole range of the phenomenon of human being, but the fact: the acting person. This fact is available in direct experience, which – in accordance with the assumptions made above – as understanding experience allows a deep penetration into the essence of the fact in question and opens the way to its proper interpretation. There is be unlimited number of facts which can become the object of human experience, but the fact that a person acts is especially distinguished among them. Given directly with full obviousness, it can be understood as the act of a person. This is possible due to the following: 1° an act is never given in isolation, as the person who is its agent is given together with it; the act is – to put it briefly – the act of a person, who appears as a person due to the fact that he is the "maker" of the act[19], 2° it is also given with a specified axiological qualification, as good or bad (which is conditioned, for example, by whether the preceding condition is fulfilled[20]); an act thus becomes a moral act, 3° the disclosure of both of these truths is possible due to the fact that the experience in which an act appears as such includes a moment of understanding. One point of this analysis must be especially emphasized: the experience of morality in its dynamic aspect is a part of human experience, and both of these experiences constitute a kind of unity. A person is disclosed by a moral act more than by a "pure" ("ordinary", morally neutral) act; on the other hand, it is through his good and bad acts that a human being becomes good or bad.[21] The creation of values in an act means at the same time the axiological creation of a human being himself – a person. This dynamic and – one could say – dialectic interdependence, is also given in experience. This is how the understanding of the empirically available fact of the person who acts leads to the discovery of a deep relationship between a person and an act, the two parts of which necessarily condition and enlighten each other. By penetrating this relationship more deeply we can uncover its essence and how it manifests itself. It turns out that this relationship is filled with consciousness which reflects and interiorises what a human being does. A human being not only acts in a conscious way, but he is aware of acting: these two experiences should not be identified with one another but indicate two different aspects of the fact that the person acts and lead to different consequences. Next to the consciousness which results in all interiorisation and subjectivisation, there occurs self-knowledge, whose activity consists in shaping the semantic side of consciousness, and most of all in objectification, and thus, in some kind of objectivisation of one's own self. One could say that if we owe the subjectivisation of everything which is objective to consciousness, then self-knowledge makes it possible to grasp the objectiveness of the "self".[22] Due to this it turns out that one's self has, as it were, two natures: a purely subjective one, grasped by consciousness and an objective one, to which self-knowledge leads us. The first can be observed in acts of reflexive (not reflective!), direct and non-intentional experience of oneself (as a subject). The second can be observed in intentional cognitive acts, capable of objectivising even consciousness itself: "consciousness integrated by self-knowledge into the whole of a real person retains its objective significance and thus also the objective status in the subjective structure of man".[23] Experiencing the fact that a person acts is extremely rich. Not only the moments of consciousness and self-knowledge appear there, but also emotional and volitive moments, which are in close correlation with the latter, often modifying them or even making their revision difficult or even impossible.[24] Also specific modi of activity reveal themselves with it, two of which are of special importance: acting as such and happening. Only the former deserves the name of act, which is a conscious and active way of a person's manifestation. The latter assumes a specific passivity which, although it is made active by happening, the "activation" never reaches the sphere of the "self" which identifies itself with subjectivity, i.e. the source of consciously performed acts. The experience of acting and of something happening confirms once more what we were talking about a moment ago, namely that the self is expressed as both subject and object. The self – this means that these experiences are available most of all to me, and the primary form is expressed in the statements: "I am acting", on the one hand, and "(something) is happening in me" and "something is happening with me", on the other. Activeness and passiveness are presented, as a consequence, as essential moments of the reaction – person – act. The data acquired due to the understanding experience of the fact that the person acts appears as more and more complete, and at the same time as ready as material for philosophical interpretation. 4. Interpretation of the experience that man acts "In translation, i.e. interpretation – we can read in The Acting Person – what is meant is that the intellectual image of an object should be adequate – should <equal> the object, and this means: it should grasp all reasons explaining the object, should grasp them in a proper way, with proper proportions between them maintained".[25] When the philosophy of human being is meant, there are two traditions which could be used to fulfill this postulate: the philosophy of consciousness and the philosophy of being. Both have specific advantages and both have shortcomings. The philosophy of consciousness is able to interpret perfectly everything that seems to be objective and internal in human experience; it tends, however, to depart from realism in the direction of idealistic solutions. The philosophy of being, culminating in the metaphysics of Thomas Aquinas, read in a modern way, guarantees a realistic solution, but it is as were designed for the analysis of what is external, and it is accustomed to looking at the human being in this aspect, i.e. from the outside. Both interpretations seem to be indispensable. Can they be brought together, enriching the philosophy of being with the philosophy of consciousness and at the same time consolidating the philosophy of consciousness in the realism of the metaphysics of being? The author of The Acting Person sets himself such a task. "An attempt at proper unification in the concept of a person and an act of these understandings which emerge from the experience of man in both its aspects must, to some degree, become an attempt at unifying two philosophical orientations, as if two philosophies. Everybody, who is aware of the depth of the cleavage between them and, as a consequence, the differences in their style of thinking and language, must admit that this task is by no means easy".[26] Let us now consider, on the basis of a few examples, how it is solved. But first – one more remark. The task in question is neither artificial nor arbitrarily chosen. The very contents of this experience requires a twofold interpretation of human experience, "internal" and "external". If we could speak about a preinterpretative assumption, it would concern only one postulate: the interpretation should be based on philosophical realism. And even this assumption is not arbitrary: first of all, it results from the general philosophical convictions of the Author; secondly – and this is what is most important here – one cannot exclude in advance that deeper penetration into the very conditions for the possibility of the interpreted experience is required. Thus, we would have an analogical situation similar to the one which we know from the analyses of R. Ingarden concerning the phenomenon of responsibility.[27] If the object of interpretation is the experiencing of the fact that a person acts, it is impossible not to notice the scholastic expression actus humanus. The noun "actus" comes from the verb "agere"; a moment of dynamism is included there, the "person-originating" origin of which is emphasized by the adjective "humanus". But it is even more important that the expression actus humanus assumes a specific interpretation, resulting from the theory in which it is involved: the objectivistic, realistic, metaphysical interpretation. "It issues – we can read in The Acting Person - from the whole conception of being, and more directly from the conception of potentia -actus, which has been used by Aristotelians (and Thomists) to explain the changeable and simultaneously dynamic nature of being".[28] Actus humanus is thus a specific interpretation of an act – closely related to the philosophy of being, and – as the Author emphasizes – "this interpretation is perfect in a way".[29] For a better understanding of this matter let us consider the meaning that the concept of act and its theory (more precisely: the theory of act and potentiality) has in the philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas. Speaking more generally, he considers act in two aspects: existential and essential. In the first perspective act occurs as the act of existence. Let us emphasize that this is the basic and – if we could say so – the chief understanding of act in the works of Aquinas. Existence, esse, is a fundamental act, and it is also the perfection of all other acts, which of necessity depend on it for their existence.[30] In the second aspect, the essential one, act is most of all (but not only) form, and thus, it is what causes the object to have a particular essence. Act is opposed to potentiality. In each case it must be understood in a different way: as a correlate of the act of existence it is, in fact, nothing (nihil simpliciter); as a correlate of form, it is matter. Moreover, Aquinas – following Aristotle – differentiates active and passive potentiality. The Latin noun "potentia" can mean one or the other; in the first case it concerns potentiality in the strict sense, and in the other power, which is a special combination of potentiality and act.[31] These two meanings of the Latin word potentia are interwoven in human experience. Human being is potentiality and human being is power. His power is a kind of realisation of potentiality and at the same time it is an existential basis for acting. His power is, thus, manifested in acts. As power belongs to the essence of man, one can say that act is something through which this essence is truly realised. To put it in other words, man is always "of some kind" in potentiality, but it is in acting that what he is becomes unveiled. This statement can be supplemented with an axiological aspect: man can be good ("can" here also means being in potentia), but his goodness is carried out (its realisation takes place) only when he acts. Realising his potentiality (capability) of being a good person, he deepens his potentiality concerning power: in acting he does not exhaust it, but – on the contrary – he strengthens it. The dynamism of man seems to be analogous to the dynamism of existence as such. "At this point metaphysics appears as the intellectual soil wherein all the domains of knowledge have their roots. Indeed, we do not seem to have as yet any other conceptions and any other language which would adequately render the dynamic essence of change […] apart from those that we have been endowed with by the philosophy of potency and act (potentia – actus)".[32] "In actualization possibility and act constitute, as it were, the two moments or the two phases of concrete existence joined together in a dynamic unity".[33] The transition from potentiality to act is becoming, fieri. Transferred to the area of human experience, it can mean both the "activation" of his passivity, which takes place in the experience of a "happening" (in me or with me), and the realisation of the potential causativeness of man, which will appear in the act. Actus points directly to fieri, and only secondarily to acting or what is happening. A closer analysis of the dynamism of man makes K. Wojtyła depart from a literal "adherence" to the pair of concepts potentia – actus, which must be replaced with the pair potentiality – dynamism in order to adequately convey the experience of this dynamism. This potentiality is power, authority, the centre of power which is dynamised not from the "outside" but from the "inside" and in this way is changed into act. The notion of dynamism emphasises the internal causality of man, and underlines the fact that his acts result from his being a subject. The fact of human dynamism, interpreted in the categories of dynamism and potentiality, unveils – as its metaphysical basis – the very existentiality of man – a person, existentiality constituted by the act of existing – esse. Without this act, which, according to Thomistic metaphysics, is the most fundamental act for the very existentiality of existence, any existential dynamism or any further realisation of it would be unthinkable. When we transfer these statements to the area of human existentiality, it would turn out that the act of existing, esse, is also an indispensable condition for all human acting, the basis that ultimately explains the very possibility of the fact that man acts. "Existence-esse lies at the origin itself of acting just as it lies at the origin itself of everything that happens in man - it lies at the origin of all the dynamism proper to man."[34] A man who acts must exist, and this must be a real existence. This truth, apparently trivial but in fact reaching the deepest of metaphysical assumptions, is expressed in the short scholastic statement: operatio sequitur esse. Karol Wojtyła often refers to this statement. And he specifies further, referring again to scholastic terminology, that this aspect of man, a subject as a being, is perfectly conveyed by the notion of suppositum. A "suppositum" is a being as such, treated, however, as a subject of existence and acting. Due to it "… the person and with it its ontological foundation have here been conceived not only as the metaphysical subject of the existence and the dynamism of the human being, but also as, in a way, a phenomenological synthesis of efficacy and subjectiveness."[35] Subjectiveness and efficacy do not exclude existence, and all the more existence as it was understood by Thomas Aquinas. Man, without giving up his subjectiveness, can be thus be treated as a "being among beings". The consequences of this statement are very far-reaching, as only man understood as a being among beings can also perform the tasks which were so beautifully described in the lecture by Dr R. Tertil: those of a servant and guard of nature. Limited by time, we cannot present here further examples of interpreting the "live" experience of man in the categories of realistic metaphysics, which can be done by referring to the analyses of the person, nature, will, participation, etc. presented in The Acting Man. But maybe what has already been said is sufficient to emphasize what we especially wanted to highlight: the parallel existence of experience and interpretation, experience and metaphysical reflection. The analysis of the fact that man acts and its implications and consequences were "screened" together with the theory of act and potentiality, and the subject that appeared in this fact found its proper interpretation through the notions of person and suppositum. The suppositum as such, grasped as the source of actually performed acts, leads us to consider its existentiality, which finally must brought us to the disclosure of its existential structure, constituted by the fact of existence, esse. In the interpretation inspired by and supported by Thomistic metaphysics one can go no further.

ConclusionThe attempt to reconstruct a fragment of the views of Karol Wojtyła about man – the acting person (as the Polish title Osoba i czyn has been translated into English) is certainly too modest to have any claims to be an adequate illustration of his philosophical method. However, we can hope that at least some of its features, especially those concerning the issue of the relationship between experience and interpretation, are visible to some degree. For the time being, this must suffice to draw some final conclusions in our lecture. What is special in the method of Karol Wojtyła as far as the illumination of live experience with metaphysical interpretation is concerned? It seems that we can apply to his whole behaviour what he said about the pair of metaphysical concepts agere – pati when he introduced them for a deeper explanation of the experimentally discovered dynamism of man: "The difference of the activeness-passiveness type that occurs between the acting of man and the happening in man, the difference between dynamic acting and certain dynamic passiveness, cannot obscure or annul the human dynamism, which is inherent in one as well as in the other form. It does not obscure in the sense of the phenomenological experience and does not annul in the sense of the need of a realistic interpretation."[36] I believe that we shall not distort the intention of the Author if we add that what is meant is that by introducing metaphysical categories we should not reduce the liveliness of experience or "flatten" its metaphysical sense, limiting it only to what is available in this experience and closing ourselves to the perspectives that can be disclosed by this sense. It seems that the metaphysical hermeneutics of phenomenological experience used by K. Wojtyła can be expressed in the three following points or postulates: