Lifestyle diseases: The burden of choice?

Share

- Details

- Text

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

Take exercise, wear seatbelts, eat the right food, stay off alcohol, and stop smoking. Is there a simple recipe for good health and Methuselan longevity? With luck and judgment, how many years of healthy life can we hope to enjoy? How much control over our health do we now have? Is living to be 100 simply a matter of choice (and personal sacrifice)?

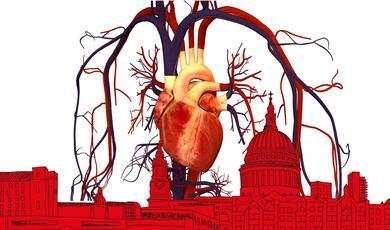

Download Text

Lifestyle diseases: the burden of choice?

Christopher Dye (dyec@who.int)

Gresham Professor of Physic

Notes on the slides, 15 March 2006

These notes and the lecture slides draw on many sources, some of which are quoted directly. I will provide these sources on request.

1. In the last lecture, I talked about the demographic transition and, in one sense, this series of lectures has followed the time trajectory from left to right in this picture. I explained back in February how the fall in deaths and the rise in life expectancy, followed by the fall in births, led to an increase in population. My theme today is about the consequences of that transition for health - the rise of the so-called "lifestyle diseases".

2. But what are "lifestyle diseases"? And what do I mean by the "burden of choice"? Have we made a choice and now suffer the burden of illness as a result? Is there an added burden to making and acting on the choice?

3. "Lifestyle disease" is in fact a poor choice of terminology. For one thing, it implies that we mostly do have a choice about what we suffer from. I will show you in this lecture that while we have choices, many of them are tough choices and limited in scope. In some instances - most obviously with respect to diseases that are due to the genes we inherit - we have no choice at all, at least until gene therapy comes along. The term "lifestyle diseases" has been used more or less synonymously with "Diseases of civilization", the "Western disease paradigm", "Diseases of affluence", "Chronic diseases", "Non-communicable diseases" and "Diseases of longevity". As a way of defining and focusing on the problem, let's have a quick look at how well these other names work.

4. In so far as obesity is due to overeating, and I'll discuss that later, "Diseases of civilization" hardly seems appropriate.

5. The "Western disease paradigm" has arisen out of thinking about the demographic transition, and rich ("Western") countries are further along that transition. But those public health specialists that are concerned with the distribution of disease globally will point out, for example, that there are more people with type 2 diabetes in low- and middle-income countries. The top 5 countries for diabetes include China, India and Indonesia, in part because of the very large populations of those countries.

6. The same argument applies to the term "Diseases of Affluence". Because of the distribution of people in the world, 80% of deaths from diseases like diabetes are in low- and middle-income countries.

7. However, the distribution of causes of deaths is very different within rich and poor countries. When we express the number of deaths per head of population, we see that most deaths in the rich world (blue) are from chronic or non-communicable diseases, whereas in the poor world deaths are more evenly distributed among infectious (communicable) and non-communicable diseases. The double burden imposed on the poor world means that the total death rate per million people each year is far greater than in the rich world.

8. The term "chronic disease" comes closer to characterizing the major problems of ill health faced by the rich world. We are talking, for example, about cardiovascular diseases (heart disease, stroke), cancer, chronic respiratory diseases and diabetes. These are among the dominant causes of long-term or chronic illness. But this discussion highlights about health another key point about the demographic transition. I've been speaking about poor countries and rich countries. Increasingly, however, we must make distinctions not only among countries but within them. When we say that poor countries (i.e. those with low average GDP) suffer a double burden of illness, we are referring to different groups of people within those countries; the gap between rich and poor within countries is widening.

9. Keep that in mind when comparing the causes of death in Asia and Africa, and western Europe and north America. In Africa, the dominant causes of death are infectious and parasitic diseases, followed by cardiovascular disease, with cancers ranked 4th.

10. In western Europe and north America, the major largest causes of death are cardiovascular diseases (heart attack, stroke) and malignant cancers, with infectious diseases barely holding their place in the top 12.

11. Diseases of longevity? As I've shown you before, we are certainly living longer, and the rise in lifespan span is unrelenting. The life expectancy of women in the leading countries has been increasing by 1 year in every 4 years for 150 years. Chronic disease are clearly associated with living longer, and the two phenomena are associated for fundamental reasons, which I will some to shortly.

12. Here are the basic facts: in rich countries, it is mostly people 45 years and over that lose years of healthy life from cancer, heart disease and stroke.

13. That said, and to emphasize again that none of these descriptors is perfect, here is the caveat. Obesity is certainly a problem in long-lived adults: very crudely speaking, the longer you over-eat, the greater the chance you will eventually get fat. But obesity is increasingly an affliction of children too - as shown here for the USA.

Overweight in children and adolescents was relatively stable from 1960 to 1980, but has sharply increased since then. One of the US national health objectives for 2010 is to reduce the prevalence of overweight from a baseline of 11 percent in 1994. The 2003-2004 overweight estimates suggest that, since 1994, overweight in youths has not levelled off or decreased, but is increasing to even higher levels. The 2003-2004 findings for children and adolescents suggest that the US is producing another generation of overweight adults, who will be at risk for related illnesses.

14. To summarize the first part. We'll settle on the term "chronic diseases". These are principally heart disease, stroke, cancer, diabetes and chronic respiratory diseases, and they are the major conditions of ill health in long-lived populations, whether these populations are in countries that are rich on average or poor on average. There is, of course, a hierarchy of causes of these conditions, and I want to focus in the next sections of this lecture on those causes that we can fix, and those that we can't easily fix. As a broad generality, we can avoid a number of the causes of cardiovascular disease (CVD). By contrast, the causes of cancer, with one or two exceptions (smoking and lung cancer) are less well-known, less predictable and therefore harder to avoid.

15. Before that, however, I want to bring in a question that is fundamental to any discussion about the origins of chronic disease: Why do we age and die?

16. It's said that life begins at 40? It does if you think that the end of the reproductive period signals the start of a new period of freedom. The sad truth is that, by age 40, we are essentially redundant in evolutionary terms. And it is evolution that has shaped our pattern of survival. These are the ages of conception of women in England and Wales in 2005, peaking in the age class 25-29 years, with hardly any women conceiving after age 40, and the average age of menopause being around 50.

17. This has some unpleasant consequences for the over 40s. Survival depends on bodily maintenance and repair. Because most wild animals die young, including humans for most of their existence, Darwinian natural selection is powerless to eliminate mutations that have their adverse effects at later ages. This is especially true if these adverse effects are coupled with traits that are beneficial in a youngster. For example, a high testosterone level may aid the drive to reproduce in a young male, but it predisposes towards health problems down the line, such as heart disease. From the perspective of natural selection, the benefit in early life counts much more than the trouble that might occur later.

18. Underlying the aging process is a lifelong accumulation of molecular faults and damage. Such damage is intrinsically random in nature, but its rate of accumulation is regulated by genetic mechanisms for maintenance and repair. As cell defects accumulate, the effects on the body as a whole are eventually revealed as age-related frailty, disability, and disease. This model accommodates genetic, environmental, and intrinsic chance effects on the aging process. Genetic effects are expressed primarily through maintenance functions, while environment (including nutrition and lifestyle) can either increase or help to decrease the accumulation of molecular damage. Cellular defects often cause inflammatory reactions, which can themselves exacerbate existing damage; thus, inflammatory and anti-inflammatory factors can play a part in shaping the outcomes of the aging process.

19. Longevity is regulated by the joint actions of many maintenance and repair pathways, which control components of systems such as those involved in antioxidant defence, DNA repair and protein turnover. Each pathway guards against the age-related accumulation of particular kinds of damage and provides a period of 'assured longevity' before the relevant lesions build up to a level that threatens survival. The plasticity of ageing and its susceptibility to environmental effects arises because many non-genetic factors, such as lifestyle and nutrition, can affect, for better or worse, the response mechanisms that deal with exposure to damage. When a mutation reduces the effectiveness of one of these mechanisms, as shown in the figure by the red cross and truncated arrow, the corresponding lesions accumulate sooner, resulting in a shorter period of assured longevity, which may shorten the lifespan of the organism as a whole.

20. Can we fix all the faults? The view of researchers like Doug Wallace make most sense to me, "...as each life-limiting process is countered, some other process will become limiting". Even if we knew how to fix the faults, the cost of fixing them may not only exceed benefits, but may simply be unaffordable in absolute terms. The hope must be that, since we can't fix all the faults piecemeal, we will be able to find common and modifiable causes to a wide array of conditions of ill health.

21. What causes of diseases can be identified and modified?

22. The answer for heart disease is that a series of well-known risk factors - to do with diet, smoking and exercise - are strong predictors of illness. Roughly speaking, and taking all these factors together, we can account for 84% of instances of heart disease. Notice that alcohol scores negative in this kind of analysis, i.e. there is evidence that it protects against heart disease.

23. The picture for stroke looks about the same. Same principal risk factors - high cholesterol and blood pressure. And once again alcohol seems to be protective.

24. This composite analysis is based on many specific studies. Here we can look at no more than one or two in detail. Trans fats (short for trans fatty acids) were invented for convenience in cooking. They are made through the hydrogenation of oils. Hydrogenation solidifies liquid oils and increases the shelf life and the flavour stability of oils and foods that contain them. Trans fat is found in vegetable shortenings, some margarines, crackers, biscuits, snack foods and chips. Trans fat increases so-called bad cholesterol, Low Density Lipoprotein (LDL), and decreases so-called good cholesterol, high density lipoprotein (HDL). The ratio of LDL to HDL determines the risk of heart disease, as in this study of 20,000 women followed over a period of 20 years.

25. Health and life expectancy vary from one part of England to another. In general, people have shorter lives in the north of the country, and in East London. We can't explain all of this variation but we can explain some of it.

26. Smoking deaths are higher in northern England and London. The gap in lung cancer deaths between men and women has reduced. Although the estimated smoking attributable mortality rate for men is more than double that for women, in 2002-04 the regional pattern is similar for both. The regional distribution for persons is shown on the map. For men, the West Midlands is also above average and for women, London is around average. Male death rates from lung cancer at ages under 75 have decreased substantially since the late 1960s, whereas those for women increased until the late 1960s, but have fallen slightly in recent years.

27. The evidence that smoking leads to premature death is abundant, but new data express the problem in a different way. There are substantial social inequalities in adult male mortality in many countries. Smoking is often more prevalent among men of lower social class, education, or income. The contribution of smoking to these social inequalities in mortality remains uncertain. In populations in England & Wales and in Poland, most (but not all) of the substantial social inequalities in adult male mortality during the 1990s were due to the effects of smoking. Widespread cessation of smoking could eventually halve the absolute differences between these social strata in the risk of premature death.

28. What about alcohol?

29. Alcohol, in moderation, does lower the risk of coronary artery disease, and many studies have now conformed that. Here, for example, a 16-year study of 50,000 US physicians found that ½ to 2 drinks a day was associated with measurably lower risk (compared with no drinking).

30. Epidemiological data support strong policy initiatives on both primary and secondary prevention. Cardiovascular risk factors can be reduced in entire populations through comprehensive and integrated prevention programmes. In patients with established coronary heart disease, there is extensive evidence on the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of secondary preventive cardiological treatments.

In several countries, the application of existing knowledge has led to major improvements in the life expectancy and quality of life of middle aged and older people. For example, deaths from heart disease have fallen by up to 70% in the last three decades in Australia, Canada, the UK and the US. Middle income countries, such as Poland, have also been able to make substantial improvements in recent years. Such gains have been realized largely as a result of the implementation of comprehensive and integrated approaches that encompass interventions directed at both the whole population and individuals, and that focus on the common underlying risk factors, cutting across specific diseases. According to WHO, the cumulative total of lives saved through these reductions is impressive. From 1970 to 2000, WHO has estimated that 14 million cardiovascular disease deaths were averted in the United States alone. The United Kingdom saved an estimated 3 million people during the same period.

31. So there are some clear causes of cardiovascular disease, which can in principle be modified. What causes of ill health cannot be modified?

32. If we do the same exercise for cancer as we did for heart disease, we get a different and more disappointing result. Now, the obvious risk factors for chronic ill health explain a relatively small fraction of all instances of cancer, with the exception of smoking. As a rough estimate, all these risk factors, taken together, explain a little more than one third of the instances of cancer. Why is that so? Why is cancer different from heart disease?

33. To explain this, we need to understand what cancer is. We have broadly two kinds of cells in our bodies: germ cells (sperm, eggs) and somatic cells (all other cells that are differentiated into various body parts, from embryonic cells onwards). The germ cells pass genetic information from parent to offspring and are in effect immortal. Somatic cells build bodies, which have a limited life span. Body cells are mortal. Cancer arises when a mutation causes the somatic cells to revert to germ-like cells.

For a single celled organism, "cancer" is not a disease, but a competitive advantage. Uncontrolled cell division is only a problem in a multicellular organism where the cells of the body (soma) must cooperate in order for the organism to pass on its genes to the next generation. Thus, the evolution of multicellular organisms has probably been the story of the accumulation of ways of suppressing dividing cells - through the accumulation of tumour suppressor genes in the genome. The tumour suppressor genes enforce the pact between the soma and the germ line. Health is not the absence of tumours but the control of tumours.

Occasionally a stem cell will suffer a mutation in a tumour suppressor gene, either because of exposure to an environmental mutagen or from bad luck with a copy error during the cell cycle. If these mutations allow the stem cell to reproduce faster than its neighbours or reduce the chance that it will die, that stem cell's progeny will tend to replace its neighbours and spread its mutation through the local tissue. That is cancer as an outcome of natural selection.

Cancer has clearly been a selective force in human evolution. The reason cancer is generally a disease of old age, is that our ancestors that had genomes susceptible to the early onset of cancer probably did not survive long enough to pass on those vulnerable genomes. Furthermore, some of the common cancers today are probably reflections of a difference between the selective forces that governed our ancestors and the modern environment and lifestyle. This can be seen in the high incidence of breast cancer. Anytime cell populations are stimulated to undergo regular bouts of proliferation and cell death, as occurs in the breasts during the female menstrual cycle, those cells are at an added risk for acquiring mutations in their genes. By studying hunter-gatherer societies, anthropologists estimate that until very recently, food shortages, early and frequent pregnancies along with breast feeding practices among our ancestors probably limited the total number of ovulations in a woman's lifetime to approximately 160. Compare this to an average of 450 ovulations in a modern American woman's lifetime.

34. So cancer is caused by genetic defects. If we could reliably identify the causes of the genetic defects, and if these causes could be modified, then we could prevent cancer. The epidemiological evidence I have shown you is not hopeful, in general, about pinning down the causes. Nor are molecular studies of how cancer arises. For example, this study was published in Nature last week. The authors used cell samples from 210 different types of cancer, and searched for mutations in the genes of these cells that are not present in those of non-cancerous cells. They found two things, both of which are bad news for prevention. First, they found many more new cancer genes than expected. Ideally we want to see few causes, not many causes. Second, the found that cancer genomes carry many unique abnormalities, not all mutations contribute equally. Taken together these two observations suggest that cancer is unpredictable, and therefore not easily preventable.

35. And to return briefly to the epidemiology, cancer trends are not as positive as those for heart disease. These are the trends in the USA for the last (nearly) 30 years for the top 10 cancers. Red is up, white is stable, and green represents a decline. For men, the picture is largely red, with the exception of lung and oral cancers that are linked to smoking.

36. To the extent that the genes we get from our parents are responsible for disease (as distinct from mutations in somatic cells), there is nothing we can do about that personally. Some good news here is that twin studies, such as those done by Kaare Christensen, suggest that genes can account for up to only ¼ of the variation in human lifespan.

37. Another way to see that is in scatter diagrams. The wide scatter of points for matched pairs of monozygotic and dizygotic twins shows that their life spans are poorly correlated. The determinants of lifespan are complex, and not down to just a few genes.

38. To bring together the last two sections, I've examined the two principal causes of chronic illness and examples of some (especially heart disease) that have known and modifiable causes, and others that do not (especially cancers). In that light, how much choice do we really have? In this assessment, I'm going to remain sober, but hopefully not too pessimistic.

39. Some parts of the advice you will find in books like this - Kurzweil's "Fantasitc Voyage" is correct, but implausibly hopeful. Kurzweil sees 3 bridges to immortality? Bridge One in which current knowledge is used to slow down the aging process. Bridge Two will be advances in biotechnology to stop disease and reverse aging. Bridge Three develops (nano)technology to create man-machine interface, expanding physical and mental capabilities.

40. This programme is truly optimistic. Take the case of antioxidants and free radicals. The "Fantastic Voyage" takes the view that more supplements are better. The more balanced, if conservative, scientific view is that the evidence in favour antioxidant supplements is ambiguous, and the mode of action is not fully understood. Therefore, "stick to tea, fruit, vegetables, wine in moderation - until there is more evidence."

41. What can we do about obesity? England has the second most obese population in the European Union. Are the English obese by choice?

42. Obesity in England is more common in the north and midlands than in the south. In Boston, they smoke, they don't eat healthily, and men can expect to die five years earlier than their counterparts in Saffron Walden. Almost one in three of the population in Boston is clinically obese - making it, officially, the fattest place in England. The difference between the two market towns, both surrounded by fresh fruit and vegetables, cannot be put down simply to poverty. There are plenty of places far more deprived than Boston which do not share its obesity problems. In England in 2003, women living in the West Midlands were most likely to be obese, while those living in London, the South East and the South West showed the lowest prevalence. For men, the prevalence of obesity was greatest among those living in Yorkshire and the Humber, while those living in London showed the lowest prevalence.

43. It's partly down to following the advice that you can find on an abundance of websites. Here, for example, is the advice to me from MyPyramid.com. The basic advice on leading a healthy lifestyle, here on diet, to avoid chronic diseases is about right.

44. At the same time , it is clear that the obesity epidemic will not be curbed just by tackling the "big two". You can't beat the 2nd law of thermodynamics, but the evidence that they are the main, direct cause of the epidemic - or that halting them would reverse it - is largely circumstantial. According to David Allison (University of Alabama), "we threw tens of millions of dollars at the best investigators in the world - and they found absolutely no effect."

45. A recent review on the International Journal of Obesity found 10 other possible explanations, listed here.

46. Some things that affect the risk of chronic illness are simply beyond our personal control. While the genes we inherit may not affect our longevity very much, there is still reason to choose your parents carefully. David Barker is famous for his "Early Origins Hypothesis" (1986), which links low birth weight to increased risk of chronic disease in later life. Trans-generational effects explain why we can expect the prevalence of chronic disease to change slowly in populations.

47. Also hard to fix on a personal level is our social predicament. It is widely recognized that if you're born poor, you will often spend your life trapped in poverty, and your children will be poor.

48. In some parts of Africa, from where these local sayings come, it is easy to recognize harsh poverty, and even partly to understand why it is perpetuated. But there are other, more subtle, long-term effects on health that arise from having little control over one's life, coupled with low social participation. This is what Michael Marmot has called the "status syndrome".

49. In summary, we do have choices to reduce the burden of chronic diseases, for example by following standard advice on diet, exercise and smoking. Some of the personal choices are tough, and will require a change to our lifestyles. Some are beyond personal control because, for example, they are about where we sit in the social pecking order. Some are unchangeable because of who our parents are. This is partly in our genes, but perhaps more importantly about the environment in which our parents lived. As the term chronic disease correctly implies, there are unlikely to be quick fixes - there's no elixir for the "Fantastic Voyage".

This event was on Thu, 15 Mar 2007

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham College plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login