Professor Marina Frolova-Walker explores the relationship between Russian opera and the state in this lecture series. Each lecture focuses on one of Russian opera’s masterpieces: Glinka’s A Life for the Tsar (1836), Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov (1872), Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk (1932) and Prokofiev’s War and Peace (1953).

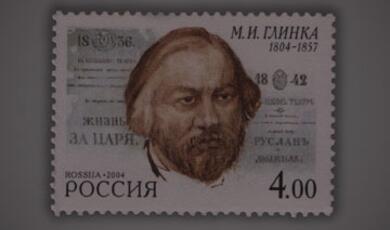

The rousing finale of Glinka’s patriotic A Life for the Tsar guaranteed it a place as the traditional season opener in Russian opera houses. A Life was a powerful and attractive presentation of the Romanov dynasty’s foundation myth, but it is also considered the first true Russian opera since its predecessors relied heavily on foreign models. A century later, with a modified libretto and a new title, it was given a new lease on life as an equally patriotic Soviet opera, Ivan Susanin (1939).

Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov is set in the ‘Time of Troubles’, using Pushkin’s incisive verse tragedy on the chaotic period preceding the establishment of the Romanovs. Such a work was bound to draw the attention of the censors, and Mussorgsky’s two versions of the opera also led to various ‘improved’ versions that conflated scenes from each. Despite all the interference it has suffered, in any of its forms, it remains a formidable exploration of power, as well as a highly moving personal drama.

Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk was more a personal than a political drama. All was well for the first two years after the opera’s première in 1934, but shortly after Stalin went to a performance, it was vigorously condemned in the state press. The pretext was the opera’s music, but it is more likely that the plot and especially the staging offended against the conservative turn in the social morality now promoted by the state. When a revival became possible, Shostakovich chose to rework the opera, renaming it Katerina Izmailova.

Sergei Prokofiev’s War and Peace was an adaptation of Tolstoy’s novel begun during WWII. He saw it as a personal interpretation of the novel, but as soon as it went forward for production, the Soviet authorities realised that this was the perfect opportunity to create a rousing epic wartime drama. A succession of cultural officials left their imprint on the work, requiring Prokofiev to make hundreds of changes and write new scenes. The composer did not live to see a complete performance on stage.

Login

Login