Singing the Laws: Ancient Greek Lawgivers in History and Legend

Share

- Details

- Text

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

While Lycurgus of Sparta and Solon of Athens are now the best-known lawgivers of Greek antiquity, there were many others, from king Minos in Crete to Zaleucus and Charondas in southern Italy. This lecture explores the specific roles attributed to Greek lawgivers in fact and legend, revealing how and why they captured later political imaginations – with mention of how some even set laws to music.

Download Text

Singing the Laws: Ancient Greek Lawgivers in History and Legend

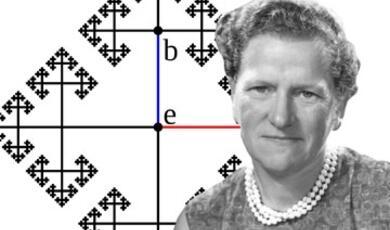

Professor Melissa Lane

26 September 2024

Introduction: nomos as a vocabulary for law and song

The title of this lecture was inspired by a text attributed to Aristotle that explores two senses of the ancient Greek word nomos (plural, nomoi): song, on the one hand, and law on the other. Here’s what it says:

‘Why are the nomoi that people sing so called? Is it because before they knew how to write, they sang their laws, so as not to forget them, as is still the custom among the Agathyrsi? And so they called the first of their later songs the same thing as their first songs’.

([Arist.] Probl.19.28 (919b38-920a4), trans. Mayhew)[1]

On this account, song and law were not accidental homonyms: because laws could be composed so as to be sung. In other words, laws could be a form of poetic composition, which for the Greeks was always imbricated with music: what we divide as lyrics and music, or poetry and music, were for them a single phenomenon (also often incorporating dance): mousikē.

If we try to understand the pervasive social presence and impact of the medium of mousikē in ancient Greece, one scholar (writing in the late twentieth century) suggested that we compare it to the pervasive social presence and impact of television.[2] But because it was more participatory (both as live audience and sometimes taking part oneself), it also involved active perceptual and motor training and habituation: something like the Metaverse, perhaps.This meant that mousikē, including singing, was a primary mode of acculturation: a way to shape the perceptual attunement and overall outlook of the members of a political community. Think of the way that Americans recite the Pledge of Allegiance – or Britons sing ‘Jerusalem’ – but then think of this kind of engagement with poetry and music as pervading all aspects of one’s life.

Because musical education was the core of Greek education, it was also the core of Greek citizenship. Before battle, for example, instead of hearing a rousing speech by a king like Henry V, Spartan law prescribed that warriors ‘be summoned to the king's tent to hear the verses of Tyrtaeus all together, holding that this of all things would make them most ready to die for their country’ (Lyc. Leoc.1.107).[3] And because all Greek education began in music, this is why learning the laws might be done in part through singing them. Our opening text (the Problemata) presented this as a kind of primitive anthropology: the peoples who sing their laws are the ones who do not yet know how to write.

But the link between nomos as law and nomos as song was not restricted to primitive societies. And this brings me to the role of the great lawgivers of ancient Greece, who are the main subjects of this lecture series. These were individual people, some of them real historical figures, others possibly legendary or semi-legendary. There were a couple of dozen of them over several centuries in the late archaic and very early classical periods: we can name them, and I’ll be introducing several of them in more detail in this lecture, and others in the lectures to come. All were men, who were called upon by their native cities, or by other cities, to frame a new set of laws – usually in circumstances of conflict or crisis, which the laws and customs that already existed there were inadequate to resolve. These laws would become the basis for the overall constitutional order for a society. (I’ll say more about the relationship between laws and constitutions next time, but for now, you can think of them as roughly coterminous – though included in the laws might be very specific ordinances about banquets and burial rituals, as well as institutional specifications of political offices, contracts, criminal laws, and so on.)

So these lawgivers acted outside the normal political processes: I’ll sometimes refer to them as ‘heroic’ lawgivers, to emphasize their relative rareness and their revered status. Their laws would be inherited and generally observed for generations to come. Later on, the laws might be amended in particular ways by the standard political process of a given society: for example, in the fifth century BCE, by a democratic vote of the Athenian assembly. But whereas we might initially think of making the laws as always a democratic action, the Greek lawgivers were more like the American Founders: framing an overall set of laws that would become entrenched and difficult to change. It’s been just 235 years since the American constitution was framed, whereas the laws laid down by the Athenian lawgiver Solon were still posted up as inscriptions in Athens nearly seven centuries after he had ordered them to be so (Pausanias, 1.18.3).

Each such lawgiver would become known as a nomothetēs—someone who lays down nomoi. To be sure, the earliest lawgivers were not said to lay down nomoi in the sense of laws: other words were used for what they produced, including thesmos, plural thesmoi, from the laying-down root. Nor was nomothetēs the only or earliest word used for lawgivers; another important word was diallaktēs (mediator, arbitrator), as I discussed in my lecture on ‘Ancient Greek Ideas of Justice’ last year.[4] Nevertheless, because the nomos and nomothetēs vocabulary did eventually become central to accounts and reflections on Greek lawgivers, and because of the connection of nomos to both law and song, I will mainly use this vocabulary.

There’s obviously more to say about what gave these lawgivers their special status and influence, what made their laws authoritative: I’ll be addressing that throughout these lectures. But for now, let’s return to music, taking a cue from Solon himself, who in the early sixth century not only made a new set of laws for his fellow Athenians, but also, put them into musical form. A later biographer recounts of Solon that he:

‘endeavoured to stretch his laws (τοὺς νόμους) into epic verse (εἰς ἔπος) when he brought them forward’. (Plut. Sol. 3.4, trans. Lane)

By setting them in epic verse, Solon was endeavouring to have his laws recited by rhapsodes at public festivals.

Another lawgiver of roughly the same time period endeavoured to have his own laws chanted in more private settings, at the kind of feast or banquet that the Greeks called a symposium. Here is the law that he made to that effect:

‘The law prescribes that all citizens know the preludes (proemia), and it prescribes that whoever is the host of the banquet recite the proemia at the feasts, after the paeans, in order that the precepts be implanted in each’. (Stob. IV 2.24, trans. Salamanca)[5]

This lawgiver was named Charondas. He was a native of Catania in Sicily, where his laws were adopted; they were also adopted in other cities. To be sure, scholars have suggested that the reference to ‘preludes’ here is probably anachronistic: the idea of ‘preludes’ to the laws was pioneered by Plato and almost certainly retrojected back to the much earlier Charondas. But the claim that Charondas might have made a law requiring that his laws be recited at each symposium, alongside the singing of paeans (a kind of choral hymn), is more plausible. It resonates with what are said to have been Solon’s efforts at the same time to put his own laws into musical verse. For both of these lawgivers, singing the laws would be a key way of inculcating them into the citizenry. And in an intriguing story, it is said that later Athenians actually sung Charondas’ laws at their own symposia: even though Charondas’ laws were not their own, they had become part of a more general musical (and political) inheritance of cultivated Greeks.[6]

Let me say something more about nomos in music. It could mean melody in a generic sense, as the poet Alcman declared: ‘I know the nomoi of all the birds’.[7] But it would also come to mean a specific kind of musical composition, set either for the kithara (a plucked instrument) or the aulos (a reed instrument), especially as perfected by the musician Terpander (who was also said to have set the Spartan laws to music). And this musical genre of nomos gives us a further clue to the link between law and lawgivers as they functioned in the ancient Greek world: for stability was central to nomos as a musical genre, just as it would be to nomos as a legal category.

Speaking of musical nomos, one scholar has said ‘the term conveys the sense of a piece of music fixed and unalterable throughout’.[8] Now as we’ll see, the laws made by the great Greek lawgivers were not totally ‘fixed and unalterable’. But they were intended to be changed only very rarely, and mainly in small details or particular respects. And those later changes would even tend to be assimilated into the laws of a heroic lawgiver: the ‘laws of Solon’ could stretch to encompass later changes that were understood to be in line with what the lawgiver had originally intended all along.

Thus the stability and identifiability of a set of laws given by a heroic lawgiver would remain core to what identified a political community. To be Athenian was to be educated in and live according to the laws of Solon (including, perhaps, their being sung). To be Spartan was to be educated in and live according to the laws of Lycurgus. One could change the laws a smidgen when necessary. But the fundamental political task was not to make new laws but rather to make good decisions (both of policy and judicial judgment) within the inherited laws.

I mention Solon and Lycurgus because they would become the best known and most significant of the ancient Greek lawgivers. You can see them on a frieze of the US Supreme Court building, along with Solon’s predecessor Draco, who imposed severe homicide laws on Athens, and other lawgivers from different cultures: we’ll be talking more about them, and also about Hammurabi and Moses, in the lectures to come. But for today, I want to concentrate mainly on some of the lesser-known lawmakers, figures like Charondas of Catania, whom I introduced earlier, and Zaleucus, from Locri in southern Italy, both part of the larger region known as Magna Graecia. Zaleucus was apocryphally said to have been Charondas’ teacher, and more importantly, was believed by the Greeks themselves to have been the very first person to have acted as lawgiver for a Greek polis.

While drawing on Zaleucus and Charondas, I will focus the rest of this lecture on two main questions. First, why did the Greeks themselves think about lawgivers? And second, why should we think about (their thinking about) (Greek) lawgivers – what difference might it make to our own thinking about law? Those two questions set my agenda for the rest of the lecture.

Why did the Greeks think about lawgivers when thinking about laws?

Greek thinkers of the classical period were acutely aware of the waves of change that had reshaped their own societies, as they had also on somewhat different time scales in nearby societies such as Egypt and Persia. Alphabetic writing had come to the Greek world from the Phoenicians probably in the 8th century BCE, with the first surviving written inscriptions in Greek dating to about then (about a century before the first surviving inscription of a Greek law, from Dreros in Crete, dated about 650 BCE). Social and economic pressures intensified in the course of the 8th to 6th centuries in the archaic elite-dominated Greek polities.

While laws had been framed in the ancient Near East for centuries (though there is scholarly debate about how to interpret their role), the emergence of the Greek lawgivers in the course of these pivotal centuries can be understood as a response to social and political pressures. Their role was not to invent law in general, or even the laws of a particular society, from scratch. Rather, it was to put together a wide-ranging set of reforms that could command sufficient social consensus among both elites and non-elites to reshape the social compact. And, while mediating between elites and non-elites, the lawgivers were also mediating figures between the human world and the divine world, between humans and gods, in the Greek imagination.

Helping Greek societies reset themselves

It follows that one important role of the heroic lawgivers was to press a reset button, to set new terms for the social compact, which could include both broad changes to political institutions and specific norms for everyday social interactions (such as how both women and men should comport themselves at funerals, one of the typical flash points for social tension). But reset buttons should not be pressed too often. So there was duality in the lawgiver’s role: reshape society, but do so as to make it relatively stable, and resistant to any future reshaping. We can call this Janus-faced (an expression referring to the Roman god or spirit of doorways, named Janus). The paradox is that the heroic lawgivers effected a revolutionary remaking of society, inculcating laws through songs and other means, such that a people’s whole identity is shaped and transformed in a certain way. But that very revolutionary reshaping was done in order to rule out future revolutionary change.

Let’s look at how that worked in practice with some accounts of Zaleucus and Charondas, and also learn more some of their specific laws in doing so.

Zaleucus

Dating to the mid-seventh century BCE, a native of the city of Locri which is found in the ‘toe’ of Italy’s boot, Zaleucus was believed by later Greeks to have been the earliest Greek lawgiver, and the first to have issued written laws, intended for Locri and later adopted in a nearby city as well.[9] We don’t know much about why or how he was chosen by the Locrians to act as their lawgiver; there are some reports that he had been a humble shepherd, even a slave, but these may be stylised or misunderstood (for example, it has been suggested that he came to be called a shepherd based on an honorary epithet for leaders of ‘shepherd of the people’).[10] It would also later be claimed that he had studied with the philosopher Pythagoras and himself became the teacher of Charondas.[11] While this was almost certainly just later hagiography, it shows that the role of the lawgiver came to be associated with special expertise and wisdom, sometimes gained through philosophy, often (especially in the cases of Solon and Lycurgus) gained through travel abroad.

Indeed, whether or not Zaleucus had travelled widely, in a motif that we will see recur with later lawgivers, his laws were not wholly original. On the contrary, he is said by a later Greek historian to have ‘arranged the written legislation (nomographias) of the Locrians in the best order, out of the Cretan, Spartan, and Areopagitic [that is, Athenian: referring to the Athenian Areopagus Council] legal customs (nomimōn)’.[12] To be sure, that conflicts with a different and much later report, that ‘he was chosen as lawmaker, and proceeded to hand down, from scratch, a completely new code of laws, beginning with the heavenly deities’.[13] But this is anomalous with regard to later lawgivers and I think much less plausible than the idea that he drew upon existing legal customs of other societies, something which later lawgivers would also do, as we’ll see.

Like Charondas, Zaleucus would be credited with having issued a ‘prelude’ to his laws, in a combined legal and musical reference; but again, this was almost certainly an anachronistic retrojection.[14] But there are some laws which Zaleucus was credited with inventing that seem more plausible. Perhaps the most striking of Zaleucus’ reported legal innovations is a law about women – in a patriarchal context, in which many societies imposed fines and restrictions on women’s expenditure and freedom of movement, especially on that of married women. Whereas in some cities, such as Athens, these laws were enforced through special officials, Zaleucus came up with a diabolically clever way of shaming married women into compliance with a law prohibiting their going out of the house (‘abroad’) in the company of a large group of attendants (taken to be a sign of excessive luxury and license):

‘A free woman could not be escorted abroad by more than one female attendant—unless she was drunk’ (Diod. Sic. 12.21, trans. Green).

The idea is a kind of double jeopardy: the aim of the law is to make free women too ashamed of the prospect of being seen out of the house with more attendants, since the law would apply to make others ‘read’ them as necessarily being drunk. Thus women would comply with the law for fear of the implications of being seen to break it.[15]

As this law shows, not all of a lawgiver’s measures had to impose coercive punishment, though some certainly did. In fact, both Zaleucus and Charondas are credited with allowing people to propose a change to the laws, but only on pain of being willing to accept immediate death should the change be rejected by the society. Here is how the story goes as told by the Athenian orator Demosthenes in the late 4th century BCE about the Locrians of his own day, who still followed Zaleucus’ laws, some three centuries later:

‘In that country…if a man wishes to propose a new law, he legislates with a halter [think of a noose] round his neck. If the law is accepted as good and beneficial, the proposer departs with his life, but, if not, the halter is drawn tight, and he is a dead man’ (Dem. 24.139).

The reason for this, Demosthenes explains, is that:

‘…the people are so strongly of opinion that it is right to observe old-established laws, to preserve the institutions of their forefathers, and never to legislate for the gratification of whims, or for a compromise with transgression…’ (Dem. 24.139).

Notice that it is not the case that the laws can never be changed: the story starts with the case of someone ‘wish[ing] to propose a new law’, after all. Nevertheless, when the same story is told elsewhere of Charondas (Diod. Sic. 12.17), it is claimed that this resulted in only three changes to the laws in some five hundred years. But whether or not these stories were simply legend, they bring out a striking feature of laws attributed to heroic lawgivers: that such laws are intended to be long-lasting, to engrave themselves in the habits of the people. The people might change the occasional later law, but not give up the whole body of the laws which a lawgiver had laid down, on pain of losing their collective life, in the sense of their life as a collective.

Charondas

Wisdom is clearly foregrounded in a late description of Charondas, also from the Greek part of Italy, who flourished likely in the sixth century BCE, making laws that were adopted by his native city of Catania as well as other cities as far away as Cos in the Aegean and Cappadocia in Anatolia, including perhaps an Athenian-sponsored Greek colony called Thourioi (sometimes transliterated as Thurii).[16] Charondas is described as:

‘the man who, after making a study of all legislations, picked out the best elements in them, which he then embodied in his own laws’.[17]

Plato would model a similar view in his dialogue called ‘The Laws’, in which the Cretan character Clinias declares of the enterprise of framing laws for a new pan-Cretan colony:

‘Our brief is to compose a legal code on the basis of such local laws as we find satisfactory, and to use foreign laws as well—the fact that they are not Cretan must not count against them, provided their quality seems superior’. (Plato, Leg. 702c2-8).

Now remember that Charondas is one of the lawgivers whose laws are said explicitly to have been sung. Unlike Solon, who set his own laws into the form of epic poetry to be recited with musical accompaniment, it seems that some of Charondas’ laws were set by others into poems to be performed with musical accompaniment. One was a law prohibiting the keeping of bad company, which inspired the composition of lines of verse in a partially lost tragedy by the Athenian playwright Euripides, which again offers a paradoxical mode of self-enforcement: rather than punish those who violate the law, one should simply classify them as being as base as their company (similar to the married women to be classified as drunk):

‘I’ve never yet questioned one who enjoys associating with bad men,

realising that he is like the very men whose company he enjoys’.[18]

The other was a law regarding men who remarry so as to bring a stepmother into a family of existing children, prohibiting them from serving as councillors to the city – another law that must be understood in a patriarchal context in which suspicion of women’s potentially malign influence was rife. This law was turned into (singable) poetry by an unknown comic poet, who specifically mentions this as a law laid down by Charondas:

‘The lawgiver Charondas, men say, in one

of his decrees, among much else, declares:

The man who on his children foists a stepmother

should rank as naught and share in no debate

among his fellows, having himself dragged in

this foreign plague to damn his own affairs.

If you were lucky the first time you wed

(he says), don’t press your luck; and if you weren’t,

trying a second time proves you insane’.[19]

While those laws may seem rather odd to the modern ear, Charondas is also credited with a very impressive and original law about literacy:

‘that all the sons of citizens should learn to read and write, and that the state should be responsible for paying teachers’ salaries’ (Diod. Sic. 12.12.4).

Some scholars have claimed that this must be an anachronism. But the move to state-supported education of various kinds was also part of Lycurgus’ legislation for Sparta, so it does not seem entirely implausible that Charondas could have passed such a law (and as Green points out, literacy in Greek was especially important for those in Greek cities in regions where the native language was not otherwise Greek).[20]

Finally, Charondas is credited with having addressed an obvious concern about any heroic lawgiver: whether they will be subject to the very laws that they have made, or whether their role exempts them from such obedience. Here, Charondas is vindicated as having obeyed his own laws. But the story is a graphic and disturbing one:

When he left town for the country, he had armed himself with a dagger as a defense against highwaymen. On his return he found the assembly in session and the populace

greatly upset, and being curious as to the cause of dissension, he went in.

Now he had once passed a law that no one should enter the assembly carrying

a weapon, and it had slipped his mind on this occasion that he himself

had a dirk [dagger] strapped to his waist. He thus offered certain of his enemies a fine

opportunity to bring a charge against him. But when one of them said,

“You’ve revoked your own law,” he replied, “No, by God, I shall maintain it,”

and with that drew his dirk [dagger] and killed himself.[21]

In this way, Charondas reinforced the stability and permanence of his laws, by showing that not even he should be allowed to break them. Having created a new set of laws for his city, he ingrained them through recitation as well as through his own example – thus making his transformative legal changes as secure as possible against wholesale further change.

Mediating between the human and the divine

I have been arguing that the heroic lawgivers were Janus-faced: they transformed their societies so as to make them proof against fundamental further reform. Another way that the lawgivers played an important role in Greek thinking was in mediating between the divine and the human. Greek lawgivers were for the most part conceived of as human, and the making of a set of laws for a given polity was the work of humans, even though the gods could be patrons of such efforts. But the Greeks were always attuned to forms of mediation and connection between humans and gods: some humans were the part-children of gods, others achieved divine or near-divine status through their own achievements. So the stories about lawgiving also exhibit a kind of duality here, another dimension of Janus-facedness.

For example, Lycurgus is described as having been told by the priestess of Apollo, who served as the oracle at Delphi, that ‘I’m in doubt whether to pronounce you man or god,

But I think rather you are a god, Lycurgus’ (Herodotus 1.65.3, trans. Godley). The fifth-century BCE historian Herodotus, who recounts this story, also remarks on the question of whether or not the laws had been dictated to Lycurgus by a god:

‘Some say that the Pythia [the priestess of the oracle] also declared to him the constitution that now exists at Sparta, but the Lacedaemonians [Spartans] themselves say that Lycurgus brought it from Crete when he was guardian of his nephew Leobetes, the Spartan king’. (Hdt. 1.65.4, trans. Godley)

Notice that the Spartans’ own belief was that Lycurgus had brought the laws defining the Spartan constitution over from Crete – just as Zaleucus was described as having (re-)arranged legal customs from Sparta, Crete and Athens in laying down his own laws. Now, as I remarked earlier, there was one tradition saying that Zaleucus had instead made his own laws entirely afresh, and a related tradition saying that these had been dictated to him in a dream by the goddess Athena, similar to how the legendary Cretan king, Minos, was held by Plato (and at least one historian in the same era as him) to have been the lawgiver for Crete, making the laws in close colloquy with his divine father Zeus.[22]

So we can see that Greek thinkers and traditions varied between the Janus faces of detecting divine influence on the lawgivers of some kind, and emphasizing their own actions and the humanness of existing or new laws. Nevertheless, I would argue that the overall emphasis was on the lawgivers as mortal beings whose effort in laying down the laws was a human one, even if some divine role (often, approval of the laws that had already been drawn up) was also imagined. In Lycurgus’ case, after having laid down the laws, he went back to Delphi to ask the oracle whether the laws were good ones for Sparta. Through the priestess, the god Apollo ‘answered that the laws which he had established were good, and that the city would continue to be held in highest honour while it kept to the polity of Lycurgus’ (Plutarch Lyc. 29.4, trans. Perrin). (There is also a story about how Lycurgus sought to ensure the continued obedience of the city to his laws, which I will save for another time.)

Likewise, another lawgiver, named Demonax, was sent by the Delphic oracle to the city of Cyrene in response to its request to the oracle for advice on its laws. On this account, Delphi did not dictate the laws, but rather, endorsed Demonax as the person to make them. Similarly, as one scholar has noted (following their discussion of the Demonax case as well), ‘The later Athenian lawgiver Clisthenes resembled Solon in that he received a commission from the community and wrote laws. He resembled Lycurgus in obtaining Delphi's approval afterwards’.[23]

While the Greeks themselves debated the nature and extent of divine influence on the sets of laws laid down by heroic lawgivers for particular cities, they generally agreed that law in general enjoyed divine sponsorship and patronage (interestingly, they did not ascribe a human ‘first discoverer’ or ‘first inventor’ for law, as they did for other arts and crafts such as coinage and sculpture.[24] The god Apollo had an association with law, as we’ve already seen; indeed, he was sometimes called Nomimos, according to the Neoplatonist Proclus, in his Chrestomathia.[25]

More widespread as a connection to fostering law in general was the goddess Demeter, who would be celebrated in her Roman guise as she who ‘first gave laws’ (Ovid, Met. 5.341-346); in Greece, she was the presiding deity of the thesmophoria festival that was ritually observed by women all over the Greek world–using another word for law, thesmos, that we noted earlier (meaning something which is laid down, from the same root as -thetēs in nomothetēs). (One Greek historian would claim that this role paralleled that of the Egyptian goddess Isis who also was credited with having established human law in general (Diod. Sic. 1.14).)

As a commentator on Vergil’s Aeneid would later explain (in Latin) of Ceres, she is called ‘legifer’, ‘lawgiver’, because:

‘before the discovery of grain by Ceres, men wandered here and there without law; this savagery was broken off when the use of grain was discovered, after the laws were born from the division of the fields’. (Serv. On Aen. 4.58)

Scholars have had a field day with this ancient comment, which connects two differently accented forms of the word nomos: one referring to pasture, so giving rise to ideas about agricultural settlement; the other referring originally to distribution (the verb nemein), which is the one from which the nomos as law sense is generally believed to have derived. Plato offered a punning definition of nomos as the ‘distribution of reason [nous]’, using the word dianomē, which can mean either ‘distribution’ or ‘regulation’.[26] Likewise, the Roman commentator on Vergil connects the distribution of land (‘the division of the fields’) to the distribution of law: like agricultural division, and indeed partly as applied to it, law is intended to give each their own. Legal justice divides and distributes, though as I argued last year in my lecture on ancient Greek ideas of justice, contrasting Solon and Rawls, it does not necessarily do so equally: there has always been a question of how much inequality can be countenanced and counted as just, as there remains today.

Why should we think about (Greek) lawgivers when thinking about laws?

I come now, much more briefly for tonight, to my second question, which was: Why should we think about lawgivers (Greek, and otherwise), when we think about law and laws? In other words, what might we learn from engaging with the Greek lawgivers and the ways in which the Greeks themselves thought about them?

This is a question that I’ll be exploring from multiple angles throughout this series. Tonight I’ve argued that the Greeks appealed to lawgivers as a way of capturing law’s potential role in framing and orienting a whole way of life—which is also, again, why they thought about the role of singing in that same project. And further, I’ve argued that while Greek lawgivers could ingrain laws through songs and other means such that a people’s whole identity is shaped and transformed in a certain way, and sought thereby to make their laws so stable as to rule out wholesale change in the normal course of events, their revolutionary actions also embodied at the time a radical remaking of society.

Thus, while (Greek) lawgivers might seem alien to a democratic age in which parliamentary assemblies make the law, or to a common law culture based on custom since ‘time immemorial’, in fact, the figure of the lawgiver is a way of capturing both the stable and the revolutionary faces of political life.

The US Supreme Court frieze, again, picturing lawgivers from many different societies and epochs, is meant to capture constitutional stability. But many of the heroic lawgivers of ancient Greece and other ancient societies—among them, Moses and Zoroaster, not to mention Lycurgus—were also the heroes of Friedrich Nietzsche when he dreamed of how ‘legislators of the future’ might be able to transform the moral code of late nineteenth century Europe. The figure of the lawgiver encapsulates at once both society as it is (as the Greeks saw in looking back to explain the history of their laws through its lens), and also, in a revolutionary mode, society as it might be. This is why thinkers from Machiavelli to Nietzsche, and revolutionaries from early modern England and France to modern Iran, have been so attracted to these figures—as I’ll discuss in the final two lectures in this series.

In conclusion: it is not essential, or inevitable, that we think about lawgivers as a way of thinking about laws. The common law takes a very different approach to law—as being originally accreted over time by judicial decisions and human custom, independently of formal statutes— as indeed did Roman law (which was more interested in the decisions of jurists and others over time than in reflecting on original intentions of any putative lawgiver (even though some Greeks living under Roman rule, such as Plutarch, would try to elevate Roman figures of lawgivers to match the Greek ones). Nevertheless, thinking about lawgivers can be a way to think about what elements of a political society we want to keep stable, and what elements we can imagine fundamentally remaking.

This might be a thought more familiar to people living in the United States, where appeals to the Founders today are very much akin to appeals made by the Greeks to their own lawgivers: these are figures credited with supreme political wisdom, who laid down laws that enjoy remarkable stability in many respects, yet who at the time brought about a major revolution in political life – albeit building on a prior society (Britain) and on learning from study and travel about the laws of other societies, both historically and contemporaneously. Some of the advantages, but also the disadvantages, of a lawgiver-focused way of thinking about law can be seen there.

For now, I think (and hope) that I have raised even more questions than I have begun to answer tonight. For example, what was the role of writing in the formulation of ancient Near Eastern and Greek laws: did laws have to be written, or could there be unwritten laws? Written and unwritten laws are the topics of my next two lectures, in the course of which we’ll dive further into Solon and Lycurgus, as well as others. In the meantime, what I hope to have shown tonight is that the Greek lawgivers intervened to shape and promulgate laws that might be borrowed from laws already existing in a given society or elsewhere, doing so in order to impress the laws on the hearts and in the habits of the citizens. Or to put it another way: singing was part of how Greek lawmaking, and political life, was done. As one of Plato’s characters would put it, acting in the role of an imagined lawgiver: ‘our songs have become our laws’ (Leg. 799e, trans. Lane).

© Professor Melissa Lane 2024/5

Ancient Sources

- Aristotle. Politics: A New Translation. Translated by C.D.C. Reeve. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing, 2017.

- [Aristotle]. Problemata. Aristotle. Problems. Edited by Robert Mayhew. Vol. 1. 2 vols. Aristotle 15–16. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University press, 2011.

- Athenaeus. The Deipnosophists or Banquet of The Learned of Athenaeus. Translated by Charles Duke Yonge. London, UK: Henry G. Bohn, 1854.

- Diodorus (Siculus). Diodorus of Sicily: Books I - II. 34. Translated by C.H. Oldfather. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1933.

- Euripides. Euripides, Fragments, edited by C. Collard and Martin Cropp Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014.

- Herodotus. The Landmark Herodotus: The Histories. Translated by Andrea Purvis, edited by Robert B. Strassler. New York, NY: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2009.

- Laertius, Diogenes. Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Translated by Pamela Mensch. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- McDonough, Christopher Michael, Richard E. Prior, and Mark Stansbury. Servius’ Commentary on Book Four of Virgil’s Aeneid: An Annotated Translation. Wauconda, IL: Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, 2004.

- Plato. Plato: The Laws. Translated by Malcolm Schofield. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

- Plutarch. Plutarch’s Lives: In Eleven Volumes. Theseus and Romulus, Lycurgus and Numa, Solon and Publicola. Translated by Bernadotte Perrin. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1959.

- Tyrtaeus. In Gerber, Douglas E., ed. Greek Elegiac Poetry From the Seventh to the Fifth Centuries BC. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999.

- Virgil. The Aeneid. Translated by Robert Fagles. New York, NY: Penguin, 2006.

Modern Sources

- Burnyeat, Myles (1999) ‘Culture and Society in Plato’s Republic’, in The Tanner Lectures on Human Values, vol. 20, edited by Grethe B. Petersen, 217–324. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

- Gagarin, Michael. (2005). ‘Early Greek Law’. In The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Greek Law, edited by David Cohen and Michael Gagarin, 82–94. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gerber, Douglas E (1997). A Companion to the Greek Lyric Poets. Leiden: Brill.

- Hansen, Mogens H. (1989). ‘Solonian Democracy in Fourth-Century Athens’. Classica et Mediaevalia 40: 71–99.

- Hölkeskamp, Karl-Joachim. (1992a). ‘Arbitrators, Lawgivers and the ‘Codification of Law’ in Archaic Greece [Problems and Perspectives]’, Mètis. Anthropologie Des Mondes Grecs Anciens 7: 49–81.

- Hölkeskamp, Karl-Joachim. (1992b). ‘Written Law in Archaic Greece’. Proceedings of the Cambridge Philological Society 38: 87–117.

- Lane, Melissa. (2024). ‘Ancient Greek Ideas of Justice’, Gresham Lecture, Barnard’s Inn Hall, London, 11 January 2004: https://www.gresham.ac.uk/watch-now/greek-justice.

- Mathiesen, Thomas J. (1999) Apollo’s Lyre: Greek Music and Music Theory in Antiquity and the Middle Ages. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press.

- Naiden, F.S. (2013). ‘Gods, Kings, and Lawgivers’. In Law and Religion in the Eastern Mediterranean: From Antiquity to Early Islam, edited by Anselm C. Hagedorn and Reinhard G. Kratz, 79–104. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Raaflaub, Kurt A. (2000) ‘Poets, Lawgivers, and the Beginnings of Political Reflection in Archaic Greece’. In The Cambridge History of Greek and Roman Political Thought, edited by Christopher Rowe and Malcolm Schofield, 23–59. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rutherford, Ian. (2020). ‘Apollo and Music’, in A Companion to Ancient Greek and Roman Music, edited by Tosca A. C. Lynch and Eleonora Rocconi, 25–36. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Svenbro, Jesper. (1993). Phrasikleia: An Anthropology of Reading in Ancient Greece. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press: 111.

- Szegedy-Maszak, Andrew. (1978). ‘Legends of the Greek Lawgivers’, Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 19: 199–208.

- Thomas, Rosalind. (1996). ‘Written in Stone? Liberty, Equality, Orality and the Codification of Law’, in Greek Law in Its Political Setting: Justification Not Justice, edited by Lin Foxhall and A. D.E Lewis, 8–31. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Thomas, Rosalind. (2006). ‘Writing, Law, and Written Law’, in The Cambridge Companion to Greek Law, edited by Michael Gagarin and David Cohen, 41-60. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Further Reading

- Fantuzzi, M. (2010). ‘Sung Poetry: the case of inscribed paeans’. A Companion to Hellenistic Literature, edited by James J. Clauss and Martine Cuyper, 181-196. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Lane, Melissa. (2013a). ‘Lifeless writings or living script? The life of law in Plato, Middle Platonism, and Jewish Platonizers’, Cardozo Law Review 34: 937-1064.

- Lane, Melissa. (2013b). ‘Platonizing the Spartan Politeia in Plutarch’s Lycurgus’, in Politeia in Greek and Roman Philosophy, eds. Verity Harte and Melissa Lane, 57-77. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Montesquieu (1989). The Spirit of the Laws, eds. Anne M. Cohler, Basia C. Miller and Harold S. Stone. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ober, Josiah. (2006). ‘Law and Political Theory’, in The Cambridge Companion to Greek Law, edited by Michael Gagarin and David Cohen, 394-411. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pöhlmann, E. (2020). Ancient Music in Antiquity and Beyond: Collected Essays (2009-2019) (Vol. 381). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG.

- Rocconi, E. (2016). The music of the laws and the laws of music: nomoi in music and legislation. Greek and Roman musical studies 4 (1): 71-89.

- Rutherford, I. (1995). Apollo's Other Genre: Proclus on Nomos and His Source. Classical Philology 90: 354-361.

- Wisner, David A (1997). The Cult of the Legislator in France, 1750-1830: A Study in the Political Theology of the French Enlightenment. Oxford: Voltaire Foundation.

- Willey, Hannah. (2016). ‘Gods and men in ancient Greek conceptions of lawgiving’, in Theologies of Ancient Greek Religion, edited by Esther Eidinow, Julia Kindt and Robin Osborne, 176-204. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

© Professor Melissa Lane 2024/5

[1] [Aristotle], Problemata, in Aristotle. Problems, edited by Robert Mayhew, 2 vols., Vol. 1. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011). This passage was called to my attention by Thomas J. Mathiesen, Apollo’s Lyre: Greek Music and Music Theory in Antiquity and the Middle Ages (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1999), 61 with n.66, who also notes that by contrast the Plutarchean Lysias (in Plutarch, De musica, 1133b-c (Ziegler 6.2-5)) ‘asserts that the term was applied to certain pieces because they were based on a particular tuning that had to be maintained throughout’.

[2] Myles Burnyeat, ‘Culture and Society in Plato’s Republic’, in The Tanner Lectures on Human Values, vol. 20, ed. Grethe B. Petersen, 217–324 (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1999).

[3] They would have heard verses by Tyrtaeus such as the following: 'It is a beautiful thing when a good man falls and dies fighting for his country' (10.1-2 West, as quoted in Kurt A. Raaflaub, ‘Poets, Lawgivers, and the Beginnings of Political Reflection in Archaic Greece’, in The Cambridge History of Greek and Roman Political Thought, edited by Christopher Rowe and Malcolm Schofield, 23–59 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 37). Tyrtaeus may also have offered one of the earliest accounts of a ‘constitution (politeia of the Spartans’, doing so again in sung verse, as noted by Douglas E. Gerber, A Companion to the Greek Lyric Poets (Leiden: Brill, 1997), 103.

[4] Melissa Lane, ‘Ancient Greek Ideas of Justice’, Gresham Lecture, Barnard’s Inn Hall, London, 11 January 2004: https://www.gresham.ac.uk/watch-now/greek-justice.

[5] This passage, as well as several others discussed in this lecture, is also discussed by an article (and author) whose work helped to guide me in beginning my own research: Rosalind Thomas, ‘Written in Stone? Liberty, Equality, Orality and the Codification of Law’ in Greek Law in Its Political Setting: Justification Not Justice, edited by Lin Foxhall and A. D.E Lewis, 8–31 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 63, which also remarks that ‘Terpander is said to have sung the laws of Sparta...’, citing Clement of Alexandria in Stromata I.78.

[6] This is stated in Athenaeus, 14.619c: ‘Charondas’ laws were sung at drinking parties in Athens, according to Hermippus in Book VI of On Law-Givers’.

[7] As translated and cited in Jesper Svenbro, Phrasikleia: An Anthropology of Reading in Ancient Greece (Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press, 1993), 111.

[8] As translated and cited in Jesper Svenbro, Phrasikleia: An Anthropology of Reading in Ancient Greece (Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press, 1993), 111.

[9] Gagarin 1986: 52; at 58, he cites as evidence for the tradition of Zaleucus being the earliest lawgiver, Ar. Frag. 548 Rose - = schol. to Pindar Ol. 11.17; and mentions, 59, that Zaleucus was a political outsider, whether or not he was originally a slave.

[10] Note 84, ad loc. to Diod. Sic. 12.20, in Green 2006: 206-07.

[11] Aristotle, Politics 2.1274a29-30.

[12] Ephorus ap Strabo 6.1.8 = FGrHist 70 F139 (Jacoby), trans. Lane. I have translated sunetaxen (from suntassō) as ‘arranged…in the best order’ in an effort to capture the military overtones of the verb (as per LSJ). Compare the vaguer translation in Andrew Szegedy-Maszak, ‘Legends of the Greek Lawgivers’, Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 19: 199–208, at 204 with n.24: ‘combined Cretan, Spartan and Areopagitic usages’; this is however an article to which I am otherwise indebted and which also discusses, and in some cases originally called my attention to, many of the ancient sources cited herein.

[13] Diodorus Siculus (12.20): ‘he was chosen as lawmaker, and proceeded to hand down, from scratch, a completely new code of laws, beginning with the heavenly deities’ (trans. Green 2010: 206-07).

[14] Diod. Sic. 12.20; see also Cicero, Leg. 2.7.8 –10.

[15] The speech act involved here is fascinating: the prohibition is enforced not by a penalty, but by a stipulative distinction.

[16] Green 2006: 196, in n.62 on Diod. Sic. 12.11.3, suggests that the dates do not work to consider Charondas as having actually been chosen as the lawgiver for the colony; rather, they may have in part adopted his legislation, possibly as promulgated by Protagoras, who is more plausible in terms of dates as a candidate to have been chosen as their lawgiver (as per Diog. Laert. 9.50).

[17] Diod. Sic. 12.11.3-4, trans. Green 2006.

[18] Euripides Phoenix fr. 812 Nauck, as trans. in Euripides, Fragments, edited by C. Collard and Martin Cropp (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014), also cited by Green ad loc. to Diod. Sic. 12.14 (Green 2006: 200 n.71), where this poem is quoted (Green’s translation there is different).

[19] As translated and quoted by Green 2006: 200, as part of Diod. Sic. 12.14; Green identifies this in n.72 as a fragment of an unidentified late comic poet (fr. adesp. 110 Kock).

[20] Green 2006: 199, in n.70 to Diod. Sic. 12.12.4.

[21] Diod. Sic. 12.19 (trans. Green 2006), though the historian adds there that ‘Certain writers, however, attribute this act to Diokles, the lawgiver of the Syracusans’.

[22] Plato, Minos 321b, with Laws 1.626a, passages I have learned much about from the work in progress of Aemann McCornack. Perlman 1992: 199 asserts that the fourth-century historian Ephorus ‘followed Plato's lead both in identifying Minos as the Cretan lawgiver and in suggesting that the Cretans continued to enjoy the laws which were laid down by him (Ephorus ap. Strab. 10.4.16, C480)’.

[23] F.S. Naiden, ‘Gods, Kings, and Lawgivers’, in Law and Religion in the Eastern Mediterranean: From Antiquity to Early Islam, edited by Anselm C. Hagedorn and Reinhard G. Kratz, 79–104 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 86, with n.24 citing Arist. Ath. 21.6 and Paus. 10.10.1.

[24] M. H. Hansen, ‘Solonian Democracy in Fourth-Century Athens’, in Connor, W. R., M.H. Hansen, K.A. Raaflaub, and B.S. Strauss, Aspects of Athenian Democracy, 71–99 (Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, University of Copenhagen, 1990), 82: ‘It was typical of the Greeks to ascribe a craft or an art or an institution to a single inventor... protos heuretes’; ‘the invention of coinage was ascribed to Pheidon of Argos; the trireme was invented by Ameinokles of Korinth; the use of fire was invented by Phoroneus; sculpture by Daidalos etc.’. As by Hansen, the phrase is usually transliterated without marking the long vowel, and I follow that usage here.

[25] Ian Rutherford, ‘Apollo and Music’, in A Companion to Ancient Greek and Roman Music, edited by Tosca A. C. Lynch and Eleonora Rocconi, 25–36 (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2020), at 29: ‘Apollo’s epithet Nomimos (oddly used instead of the usual Nomios) derives from this practice’, giving the reference as Chrest. 320A35.

[26] I am grateful to Jiseob Yoon for discussing this passage with me, which is also discussed in her doctoral dissertation, The Role of Law in Plato’s Cities, Princeton University, September 2024 (embargoed for publication for two years).

Ancient Sources

- Aristotle. Politics: A New Translation. Translated by C.D.C. Reeve. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing, 2017.

- [Aristotle]. Problemata. Aristotle. Problems. Edited by Robert Mayhew. Vol. 1. 2 vols. Aristotle 15–16. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University press, 2011.

- Athenaeus. The Deipnosophists or Banquet of The Learned of Athenaeus. Translated by Charles Duke Yonge. London, UK: Henry G. Bohn, 1854.

- Diodorus (Siculus). Diodorus of Sicily: Books I - II. 34. Translated by C.H. Oldfather. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1933.

- Euripides. Euripides, Fragments, edited by C. Collard and Martin Cropp Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014.

- Herodotus. The Landmark Herodotus: The Histories. Translated by Andrea Purvis, edited by Robert B. Strassler. New York, NY: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2009.

- Laertius, Diogenes. Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Translated by Pamela Mensch. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- McDonough, Christopher Michael, Richard E. Prior, and Mark Stansbury. Servius’ Commentary on Book Four of Virgil’s Aeneid: An Annotated Translation. Wauconda, IL: Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, 2004.

- Plato. Plato: The Laws. Translated by Malcolm Schofield. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

- Plutarch. Plutarch’s Lives: In Eleven Volumes. Theseus and Romulus, Lycurgus and Numa, Solon and Publicola. Translated by Bernadotte Perrin. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1959.

- Tyrtaeus. In Gerber, Douglas E., ed. Greek Elegiac Poetry From the Seventh to the Fifth Centuries BC. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999.

- Virgil. The Aeneid. Translated by Robert Fagles. New York, NY: Penguin, 2006.

Modern Sources

- Burnyeat, Myles (1999) ‘Culture and Society in Plato’s Republic’, in The Tanner Lectures on Human Values, vol. 20, edited by Grethe B. Petersen, 217–324. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

- Gagarin, Michael. (2005). ‘Early Greek Law’. In The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Greek Law, edited by David Cohen and Michael Gagarin, 82–94. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gerber, Douglas E (1997). A Companion to the Greek Lyric Poets. Leiden: Brill.

- Hansen, Mogens H. (1989). ‘Solonian Democracy in Fourth-Century Athens’. Classica et Mediaevalia 40: 71–99.

- Hölkeskamp, Karl-Joachim. (1992a). ‘Arbitrators, Lawgivers and the ‘Codification of Law’ in Archaic Greece [Problems and Perspectives]’, Mètis. Anthropologie Des Mondes Grecs Anciens 7: 49–81.

- Hölkeskamp, Karl-Joachim. (1992b). ‘Written Law in Archaic Greece’. Proceedings of the Cambridge Philological Society 38: 87–117.

- Lane, Melissa. (2024). ‘Ancient Greek Ideas of Justice’, Gresham Lecture, Barnard’s Inn Hall, London, 11 January 2004: https://www.gresham.ac.uk/watch-now/greek-justice.

- Mathiesen, Thomas J. (1999) Apollo’s Lyre: Greek Music and Music Theory in Antiquity and the Middle Ages. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press.

- Naiden, F.S. (2013). ‘Gods, Kings, and Lawgivers’. In Law and Religion in the Eastern Mediterranean: From Antiquity to Early Islam, edited by Anselm C. Hagedorn and Reinhard G. Kratz, 79–104. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Raaflaub, Kurt A. (2000) ‘Poets, Lawgivers, and the Beginnings of Political Reflection in Archaic Greece’. In The Cambridge History of Greek and Roman Political Thought, edited by Christopher Rowe and Malcolm Schofield, 23–59. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rutherford, Ian. (2020). ‘Apollo and Music’, in A Companion to Ancient Greek and Roman Music, edited by Tosca A. C. Lynch and Eleonora Rocconi, 25–36. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Svenbro, Jesper. (1993). Phrasikleia: An Anthropology of Reading in Ancient Greece. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press: 111.

- Szegedy-Maszak, Andrew. (1978). ‘Legends of the Greek Lawgivers’, Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 19: 199–208.

- Thomas, Rosalind. (1996). ‘Written in Stone? Liberty, Equality, Orality and the Codification of Law’, in Greek Law in Its Political Setting: Justification Not Justice, edited by Lin Foxhall and A. D.E Lewis, 8–31. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Thomas, Rosalind. (2006). ‘Writing, Law, and Written Law’, in The Cambridge Companion to Greek Law, edited by Michael Gagarin and David Cohen, 41-60. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Further Reading

- Fantuzzi, M. (2010). ‘Sung Poetry: the case of inscribed paeans’. A Companion to Hellenistic Literature, edited by James J. Clauss and Martine Cuyper, 181-196. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Lane, Melissa. (2013a). ‘Lifeless writings or living script? The life of law in Plato, Middle Platonism, and Jewish Platonizers’, Cardozo Law Review 34: 937-1064.

- Lane, Melissa. (2013b). ‘Platonizing the Spartan Politeia in Plutarch’s Lycurgus’, in Politeia in Greek and Roman Philosophy, eds. Verity Harte and Melissa Lane, 57-77. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Montesquieu (1989). The Spirit of the Laws, eds. Anne M. Cohler, Basia C. Miller and Harold S. Stone. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ober, Josiah. (2006). ‘Law and Political Theory’, in The Cambridge Companion to Greek Law, edited by Michael Gagarin and David Cohen, 394-411. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pöhlmann, E. (2020). Ancient Music in Antiquity and Beyond: Collected Essays (2009-2019) (Vol. 381). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG.

- Rocconi, E. (2016). The music of the laws and the laws of music: nomoi in music and legislation. Greek and Roman musical studies 4 (1): 71-89.

- Rutherford, I. (1995). Apollo's Other Genre: Proclus on Nomos and His Source. Classical Philology 90: 354-361.

- Wisner, David A (1997). The Cult of the Legislator in France, 1750-1830: A Study in the Political Theology of the French Enlightenment. Oxford: Voltaire Foundation.

- Willey, Hannah. (2016). ‘Gods and men in ancient Greek conceptions of lawgiving’, in Theologies of Ancient Greek Religion, edited by Esther Eidinow, Julia Kindt and Robin Osborne, 176-204. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Part of:

This event was on Thu, 26 Sep 2024

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham College plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login