Tuberculosis: A Cultural History

Share

- Details

- Text

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

Tuberculosis (and especially drug resistant strains) is a major global health problem, with over nine million people developing the disease annually and 1.5 million dying from it. The history of TB reveals the complex and often contradictory meanings assigned to this disease. The terms used to talk about TB – phthisis, consumption, the “white plague”, and the “wasting disease”, for example – reveal a great deal about popular perceptions relating to contagion and individual social responsibility.

Download Text

Tuberculosis: A Cultural History

Professor Joanna Bourke

6th October 2022

What does tuberculosis look like? If we are thinking about the early-nineteenth century, we might imagine an emaciated, white, male artist coughing up blood onto a white pillowcase. As he presses a handkerchief to his fevered brow, his eyes burn with creative genius. Fast-forward fifty years and a very different image might come to mind: perhaps, an impoverished, white, female mill worker. She is lying on a cheap, metal-framed bed in a bare room or perhaps in the consumptive ward of a sanatorium. Today, our image might be of an HIV-positive, young, Black man or woman eking out a living in a South African or Haitian shanty town. After all, since the 1980s, when international health organizations judged TB to be a global epidemic, scientists have been aware of the co-morbidity of HIV and tuberculosis: being infected with HIV makes a person vulnerable to TB and TB can activate HIV. Forty years before the announcement of a global epidemic – due to the development of streptomycin in 1944 – it was assumed that TB would eventually be relegated to history. But drug resistant strains have meant that it remains endemic. In 1961, the World Health Organization (WHO) found that one-fifth of TB cases in Kenya were drug resistant, largely due to ineffective health communication which meant that sufferers often failed to complete the full course of treatment. Today, one in every three people globally are infested with mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB), which is a necessary (although not sufficient) precondition for the disease. TB is responsible for one in four preventable deaths. It is a testament to the skewed priorities of current global capitalism that only one in five TB patients around the world have access to an effective treatment programme. Many public health experts argue that deaths from TB are one of the most reliable indexes of human well-being and societal equality: something must therefore be desperately wrong. What can a cultural history of this disease contribute to debates today?

Tuberculosis was the most feared disease of the nineteenth and early twentieth century. In 1903, the President of the American Public Health Association lamented the ‘slow and insidious’ spread of TB, contending that it had become the ‘scourge of the human race’. Called the ‘Captain of Death’, the ‘white plague’, the ‘wasting disease’, and ‘consumption’, it literally ‘consumed’ the bodies and minds of millions of people. In nineteenth and early twentieth century Britain, the disease killed one in every eight children, men, and women. It was the greatest single killer of men; for women, it ranked a close second in lethality to heart disease. Furthermore, these statistics are colossal underestimates. Such was the stigma of being labelled a ‘consumptive’ that sufferers routinely sought to hide or deny their symptoms for as long as possible.

The cultural obsession with consumption is reflected in the innumerable novels, poems, theatre plays, and songs (notably Victoria Spivey’s classic ‘T.B. Blues’, written in 1927). Famously, Irish novelist James Joyce was preoccupied with the disease. In his 1922 classic Ulysses, set in Dublin in 1904, Joyce memorably describes the bronchitic headmaster Garrett Deasy, whose ‘coughball of laughter leaped from his throat dragging after it a rattling chain of phlegm’. The novel also portrays ‘consumptive girls with little sparrow’s breasts’ and the ‘sunken eyes, the blotches of phthisis and hectic cheekbones’ of a lawyer named J. J. O’Molloy. Joyce describes the way O’Molloy ‘applies his handkerchief to his mouth and scrutinises the galloping tide of rosepink blood’.

However, Joyce’s most poignant description of TB can be found in ‘The Dead’, published in the short stories collection Dubliners in 1914. The setting of the entire story is tubercular – even the doorbell is ‘wheezy’ and the festivities are interrupted by ‘high-pitched bronchitic laughter’. Characters exchange news about the benefits of a ‘bracing air’ and there are ominous allusions to people suffering ‘colds’. The climax of ‘The Dead’ revolves around the singing of a traditional Irish ballad about the frailty of love and untimely death. When a central character called Gretta Conroy hears ‘The Lass of Aughrim’ being sung, she becomes upset, confessing to her husband Gabriel that her ‘very delicate’ lover (a seventeen-year-old Galway man named Michael Furey) used to sing it to her. Furey had tuberculosis and was ‘in his lodgings in Galway and wouldn’t be let out’ because he was ‘in decline’. Gretta explains that, when Furey heard that she was migrating to Dublin, he escaped his sickbed, made his way to her house, and sang to her under a tree in the rain. Furey’s reckless excursion sparked the acute phrase of his TB: a week later, he was dead. In ‘The Dead’, Gabriel becomes jealous of the ‘lonely churchyard’ in Oughterard where ‘Michael Furey lay buried’.

‘The Dead’ lays bare a hidden, personal history. The story drew directly from Joyce’s own life. His lover, Nora Barnacle, resembles Gretta Conway. She, too, had been in love with a Galway man called Michael Bodkin. In 1903, after Michael had been diagnosed with tuberculosis, Nora broke off the relationship, telling him she was leaving for Dublin. Ignoring his doctor’s advice, Bodkin made his way to Nora’s home and, in the pouring rain, sang a farewell song under an apple tree. The chill aggravated his TB and he died. According to Nora’s sister Kathleen, Joyce was jealous of the dead-Bodkin, feeling a ‘rivalry with a dead man buried in the little cemetery at Rahoon’.

But ‘The Dead’ does more than simply echo Joyce’s personal trauma. It also exposes an underlying anxiety about tuberculosis in Ireland at the turn-of-the-century. Joyce was writing in the early years of the twentieth century, when Ireland had the fourth highest morality rate from pulmonary tuberculosis in the world, exceeded only by Hungary, Austria, and Serbia. Particularly vulnerable were young men and women between the ages of 15 to 45 years of age. Unlike America and England, where the disease peaked in 1850 and 1870, respectively, in Ireland, it raged well into the first decade of the twentieth century. It was popularly dubbed the ‘Irish disease’. Even the Sinn Féin Weekly grumbled that the nation’s reputation as a hotbed of TB meant that tourists and travellers would ‘hesitate to visit’, believing Ireland to be a ‘pestilent jungle inhabited only by consumptive patients’.

The prevalence of the disease in Ireland provoked widespread speculation. ‘Why is Tuberculosis so Common in Ireland?’, asked the distinguished physician John Byers in his 1907 lecture at the Tuberculosis Exhibition in Lurgan. As the Professor of Midwifery and the Diseases of Women and Children at Queen’s College Belfast, Byers systematically reviewed the most common answers to that question. Was Ireland’s damp climate and boggy land responsible? Could high levels of emigration have made a difference, since the strong and healthy citizens deserted the island, leaving behind ‘a physically inferior population – a race of weaklings who propagate weaklings—all very susceptible to phthisis’? Or did the Irish ‘race’ itself provide a fertile ‘soil’ upon which the tubercule bacillus could grow ‘with extraordinary facility’? Although Byers agreed that these explanations had some merit, he maintained that they were inadequate. Instead, he blamed the Irish people themselves. Their lack of education about sanitation, nutrition, and housing had left them unable to ‘grapple with the white plague’. Byers chastised his fellow Irish men and women for their ‘excessive use of alcohol’ and ‘increased use of tea and white household bread instead of the old porridge and buttermilk’. Children were being fed infected meat (Byers estimated that at least 30 per cent of milch cows in Ireland were tubercule). Adults possessed unsanitary habits which, when combined with crowded accommodation and poor ventilation, helped spread the microbe. Furthermore, unlike the rest of the U.K., infected Irish patients had limited access to segregated housing. Byers urged the government to impose compulsory notification of TB, establish sanatoriums, inspect abattoirs, and promote public education (especially of ‘our mothers and our wives and our sisters’) in temperance, cleanliness, and sanitation. In his words, ‘we must teach the people that they themselves have it in their own power largely to control the disease’. As we will see throughout this series of talks on the ‘cultural history of disease’, sick people (especially female and minoritized ones) were routinely blamed for their own afflictions.

Byers was writing at a particular time (1907) and place (Ireland). However, knowledge of the disease, which only came to be called tuberculosis in the 1880s, dates to ancient times. Archaeologists have found evidence of the disease in 5800 B.C.E. in Europe and 4500 B.C.E. in the Near East. DNA and mycolic acid analyses reveal that it was present in North America by 1000 C. E. and in South Africa by 300 C. E. The forms of disfigurement typical of TB appears in ancient art. One of the earliest descriptions of the disease can be found in the writings of Hippocrates (460-370 BC), who called it ‘phthisis’, from the Greek meaning ‘to decay or waste away’. For him, it was the result of humoral imbalances. It was Aristotle (384-322 B.C.E.) who observed that phthisis was contagious, as did Galen in the second century. By the fifteenth century, the Italian physician and early epidemiologist Hieronymus Fracastorius could confidentially announce that the contagious nature of phthisis was not due to any ‘occult properties’ but were carried through the air. By the late seventeenth century and early eighteenth centuries, Enlish physicians as different as Richard Morton and Benjamin Marten linked the disease to infection by minute ‘animalcula’. Benjamin Rush, the doyen of American medicine in the early years of the Republic, believed TB was caused by systemic underlining debility that weakened the ‘serum’ or blood, causing hypersecretions from the bronchial vessels. A person’s underlying weakness was ‘ignited’ by puberty, humoral imbalances, or grief.

The actual microorganism was not discovered until 1882 when Robert Koch christened it ‘tubercle bacillus’. From that date onwards, scientists throughout the world dedicated their labours to investigating its properties and propensities. They were able to show that between one-third and forty per cent of TB patients expelled copious tubercle bacilli whenever they coughed and that these bacilli could be ejected for up to ten feet. The bacilli adhered to bedding, food, clothing, furniture, as well as sticking to the hands and faces of people around the inflicted person. As Koch lamented, bacilli were ‘scattered everywhere’, with ease. Its main symptoms are coughing blood, fever, weight loss, night sweats, and facial pallor. It could be chronic (with patients surviving for decades) or ‘galloping’, resulting in an agonising death.

But the disease named tuberculosis was not just the bacillus. It has become a truism to state that TB is a ‘social disease’. Of course, this is not to deny that respiratory TB is an infectious bacterial disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB). But culture gives meaning to nature. Many people are infected with MTB, but it remains latent until the person’s immune system is compromised by stress, poor diet, inadequate accommodation, poverty, malnutrition and, in recent decades, HIV/AIDS. In other words, MTB is a necessary (although not sufficient) cause of illness. Furthermore, what happens in our bodies can only be understood through the prism of the world around us. The language used to refer to the disease affects people’s responses to it. As the names change – phthisis, scrofula, wasting disease, decline, consumption, the ‘white plague’, the ‘Captain of Death’, or tuberculosis, for example – so too does the meaning ascribed to being ill. Culture, not nature, determines how people feel and act. For example, in the shift from being labelled a ‘consumptive’ to becoming ‘tubercular’, patients shifted their emphasis from the disease’s effects on their bodies (‘consuming’ it) to the ‘invasion’ of a bacteria (requiring a ‘war’ to destroy it). Rather than being seen as passive sufferers, embracing their fate, they were supposed to physically as well as metaphorically ‘labour’ to destroy the bacterium, all guns blazing. As the contagious nature of the disease became more well-known, emphasis also shifted from an individual’s ‘constitution’ to questions of civil responsibility and regulation. An individual’s ‘constitution’ and therefore his or her need for isolation (Michael Furey in Joyce’s ‘The Dead’ was confined ‘in his lodgings in Galway and wouldn’t be let out’ because he was ‘in decline’) took second place to conducting a societal ‘Warfare Against Tuberculosis’, as American professor of preventive medicine Mazyck P. Ravenel entitled an article in a 1903 edition of the Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. By becoming a ‘tragedy of obviable disease and needless death’, an array of professionals – from physicians, sanatorium managers, and statisticians – had to be recruited to count and manage populations of sick people.

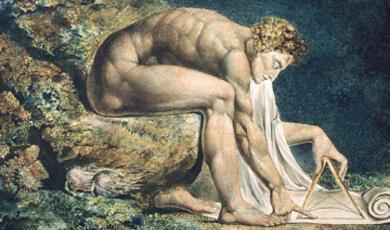

When, how, and why did these shifts in meaning take place? One of the most important changes occurred between the eighteenth century and the nineteenth centuries. In the earlier period, the ‘wasting disease’ was often romanticized (the white, emaciated, male genius image conjured up at the start of this talk). This was what Susan Sontag was alluding to in Illness as Metaphor when she contended that TB was the obverse of cancer. In her words, ‘As TB was the disease of the sick self, cancer is the disease of the Other’. Like gout in the eighteenth century, which came freighted with ideas of aristocratic indulgence, TB was a romantic, aestheticized disease of creative minds. It gave middle-class and upper-class sufferers an enhanced sense of self. As historians of medicine Clark Lawlor and Akihito Suzuki explain in ‘The Disease of the Self: Representing Consumption, 1700-1830’, as the eighteenth century progressed, consumption ‘became ‘a marker of individual sensibility, genius, and general personal distinction’. Its

“heightened representation in literature and art reflects, and to some extent reinforces, its perceived cultural value to the self. This perception was strengthened by the age-old belief, both popular and professional, that consumption could be caused by mental upset of various kinds, especially that caused by a precocious intellect, academic overwork, or merely a hypersensitive poetic or creative sensibility.”

In literature, female consumptives were portrayed as being transformed by TB into supremely aesthetic, passive, and spiritual creatures. For example, in Samuel Richardson’s 1748 epistolary novel entitled Clarissa, the lead character’s physical fragility, slenderness, and love melancholia caused by the disease gives her an ethereal beauty. In contrast, the disease actively stimulated the creative power of male consumptives. This view drew on Brunonianism – that is, the Scottish physician John Brown’s view that the body contains a fixed amount of ‘excitability’ that needed to be kept in balance. Tuberculosis over-stimulated both body and brain, engendering forms of genius that could not be sustained. Commentators could draw attention to numerous examples of creative consumptives, including philosopher Immanuel Kant, pianist Frédéric Chopin, and writers as diverse as John Keats, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Ralph Emerson, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Anton Chekhov. The image of the consumptive as a refined and sensitive individual could also be illustrated by pointing to artists such as French painter Jean-Antoine Watteau in the early eighteenth century, nineteenth century Russian painter Marie Bashkirtseff (a rare example of a creative female consumptive – but, then, she died aged 25), and twentieth century Norwegian artist Edvard Munch, English illustrator Aubrey Beardsley, and Italian painter Amedeo Modigliani. Lawlor and Suzuki argue that this ‘fantasy’ of the consumptive as a person of exquisite taste and sensibility was so powerful that sufferers ‘would attempt to live (and die) according to its image’. In the 1820s, the link between TB and enhanced artistic sensibility was so entrenched that Lord Byron quipped that ‘I look pale – I should like to die of a consumption…. Because the ladies would all say, “Look at that poor Byron, how interesting he looks in dying”’. The French poet Théophile Gautier went so far as to contend that when he was young, he ‘could not have accepted as a lyrical poet anyone weighing more than ninety-nine pounds’. The sensitive, delicate, and slender bodies of male consumptives testified to social and creative distinction. Their deaths were dramatizations of their ability to transcend the hustle and bustle of vulgar, modern, industrialised life. These sufferers (both male and female) were framed as ‘invalids’ more than ‘patients’: they were deserving of the support of their families and friends, as well as the veneration of their communities.

This romanticized image of the consumptive did not last. Industrialization and urbanization, with their accompanying fears linked to the dangers of ‘miasma’ (that is, the belief that diseases were caused by ‘bad air’), minute ‘animalcula’ (the old term for microscopic organisms), and then ‘germs’ shifted anxieties about disease transmission towards blaming impoverished ‘Others’. The moral responsibility for this disease was assigned to the working classes, with their allegedly dirty and disgusting habits. As we saw at the start of this talk, Byers assigned responsibility for the spread of the disease to mothers, wives, and sisters – that is, it was women’s role to spread temperance, cleanliness, and sanitation. In particular, poor women were vectors of disease (and affluent women were expected to be their educators). Women’s bodies were the ‘soil’ that harboured disease. Women gave birth to infants already containing the ‘seed’ of TB; their inept cooking of cheap cuts of meat and their purchase of cheap, infected milk imperilled their families; their unsanitary housekeeping spread risk to middle-class homes; their promiscuity infected middle- and upper-class ‘family men’ who consorted within their ‘homes of vice’.

This was not only a gendered discourse. It was highly raced. As we have seen, in the eighteenth century, consumption was racialized as a disease of white, creative types. But nineteenth century commentators increasingly linked the disease to minoritized ethnic groups. Medical and other experts in Los Angeles, for example, blamed ‘Mexicans’ for spreading the disease, leading to calls for tightening border controls, introducing more rigorous medical checks, and deporting and repatriating as many as possible. In South Africa, fears of an ‘epidemic’ of TB, especially in parts of the southeast region where more than 90 per cent of adults were infected, resulted in similarly repressive policies. White governmental responses included introducing exclusionary policies and clearances designed to safeguard white communities. In other words, instead of fundamental policies to tackle the poverty, malnutrition, and discrimination that were facilitating the flaring up and then spread of the disease, local authorities and governments adopted policies of removal and racial segregation. Similar movements of blaming immigrants occurred in locales as different as colonial, white Australia, where it fuelled a nativist rhetoric based on a mythic ‘pure’ Australia, and in post-war Britain, where Asian immigrants were targeted. The result was inadequate and highly damaging policies founded on racialized and racist agendas.

A useful case study of racialized responses to TB can be seen by looking at the Indigenous peoples of the U.S. These populations had extremely high rates of infection. According to some estimates, over half of Navajo had TB. In 1949, the Director of Medical Services in the Bureau of Indian Affairs was appalled to find that the rate of TB overall in the U.S. was 33.4 per 100,000, whilst it was 302.4 amongst the Navajo. Tuberculosis patients amongst the Navajo were also more likely to die: there was a ratio of nine Navajo deaths from TB to one in the ‘general population’. These elevated levels were the direct result of governmental neglect and underdevelopment, which had resulted in crowded accommodation, contaminated water supplies, poverty, and low life expectancy (in the 1950s the life expectance of people in the Navajo reservations was less than forty years, compared with seventy throughout the U.S.). The crisis was so huge that, in November 1949, the editors of the American Journal of Public Health and the Nation’s Health called it an ‘Indian massacre’ due to ‘neglect to an extent which is truly “a disgrace to the nation”’.

How did physicians at the time explain this health crisis? Three theories were influential: ‘culture’, ‘virgin soil’, and racial weakness. All three were linked to ‘blood quantum’ or the degree of ‘Indian blood’, in the sense that ‘full bloods’ were more vulnerable than ‘half-bloods’ (a completely spurious concept). Although epidemiological research from the 1930s had established that there was a link between poverty and TB, the idea that Indians were particularly susceptible to the disease due to ‘cultural’ practices (for example, the Sioux people were chastised for their pipe smoking and religious dances) and their ‘primitive’ bodies had a long life. Referring to the Crow people, an author in the Medical Record in 1892 contended that

“Their resistance to disease is much less than that of the civilized races, I have seen the evidence at the bedside, in watching them yield and die from diseases that I felt sure any stout white man had easily thrown off.”

The Rev. D. A. Sanford promoted a particularly racist indictment of Indian ‘idleness and vice’. In ‘What Is Killing Our Indians?’, published in the September 1901 edition of The Indian’s Friend, Sanford claimed that TB was ‘inherited from past generations’, so it was ‘in their blood’. Although pointing a finger at paternalistic, white, governmental policies, Sanford was adamant that indigenous Americans were responsible for their own condition. In his words,

“As is well-known[,] an active out-of-door life, such as Indians led in their wild state,… tends to throw off this disease. Instead of this the government has been giving them rations, interest money, and lease money, all of which have fostered idleness. The young man who has been in school has been given a ration ticket, he draws interest money, his land is leased, he has money to spend, the vices of civilization tempt him, and then idleness and vice help to develop the tubercular disease which he has inherited.”

In case readers were in any doubt about who was truly responsible, Sanford reiterated his main argument that ‘Indian habits’ were ‘blameworthy”.

‘Virgin soil’ theory was the second most influential explanation for the susceptibility of indigenous peoples to TB. According to this theory, indigenous Americans were particularly vulnerable because, until recent times, they had limited exposure to the disease so were immunologically vulnerable. As historian Christian McMillan explains in ‘”The Red Man and the White Plague”: Rethinking Race, Tuberculosis, and American Indians, ca. 1890-1950’, the ‘virgin soil’ theory assumed a racialized body: ‘”primitive” people had to wait for their biology to catch up with civilization. Some caught up faster than others’. One of the consequences of ‘virgin soil’ theory was that external methods of disease control were considered unnecessary since the most genetically vulnerable people would die, leaving behind resistant indigenous populations. This was a view espoused by Esmond R. Long, Director of The Henry Phipps Institute at the University of Pennsylvania and Director of Research and Therapy at the National Tuberculosis Association. As he put it in 1948 at a meeting of the American Philosophical Society,

“The extraordinary malignancy of tuberculosis in primitive peoples meeting tuberculosis for the first time furnishes a clue to the past history of all peoples…. The stage was set long ago for the vast operation of natural selection in the contest between tuberculosis and man. We have reason to believe that the racial groups of today stand in different stages of the survival of the fittest. Indians, Negroes, Eskimos, and Pacific Islanders are in mid-stages. The white race, after five thousand years of association with the tubercle bacillus, is in a late stage.”

Such racist thinking changed only slowly. From the 1930s, physicians and other commentators were increasingly recognising the role of poverty, overcrowding, and poor diet in triggering the disease. The idea of ‘race’ was also being questioned, although it was replaced by a similarly nebulous concept of ‘culture’. Nevertheless, persistent unwillingness to invest in health care on ‘Indian’ reservations combined with continued and extreme poverty meant that disease remained a problem.

Unfortunately, many modern historians echo ‘virgin soil’ arguments, by tying it into broader debates about the racialization of illness (for example: African Americans and syphilis). This was the point being made by David S. Jones, who criticised fellow historians for taking ‘virgin soil’ arguments at face value. He argues that there is little evidence that immune deficiencies were the cause of mass deaths. After all, TB was present in pre-contact indigenous groups and, by the nineteenth century, these communities had had substantial contact with Europeans. There was no ‘virgin soil’. So why have ‘virgin soil’ arguments remained so persuasive? Jones suggests that their popularity is due to three factors: the ‘elegance of immunological determinism’, reactions against the ‘economic determinism’ of Marxist traditions, and the ideological and psychological satisfactions of deflecting attention from the impact of colonialism to an ‘innate’, morally neutral biologism. In Jones’ words,

“theories of immunological determinism can still assuage Euroamerican guilt over American Indian depopulation, whether in the conscious motives of historians or in the semiconscious desires of their readers.”

These explanations are much ‘safer’ than ones that point to the role of colonialist economic exploitation, cultural appropriation, population dislocation, and gross levels of inequality.

Arguments based on ‘inferior cultures and bodies’, ‘virgin soil’, and ‘blood quantum’ have been made with regards other groups as well. Ernest A. Sweet targeted Mexicans. His study of interstate migration in the States of Texas and New Mexico was published in Public Health Reports in 1915. Sweet contended that the ‘fearful ravages of tuberculosis among primitive people has long been noticed’, but blamed this on an alleged ‘low racial immunity’ due to their ‘large admixture of Indian blood’. Sweet contended that Mexicans never developed resistance to TB

“because they have never fought the infection through successive generations. Just as in children the susceptibility decreases as age increases, so in races the further removed they are from civilization, the more susceptible they are to the disease.”

Although Sweet did dedicate considerable space discussing the impact of poverty, appalling housing conditions, poor nutrition, and lack of sanitation, he concluded by blaming Mexicans for their economic predicament, claiming that they were ‘ignorant and superstition’, as well as morally suspect because they were plagued by syphilis. As historian Emily Abel explains, ‘in an era that idealized strength and vigor’, the argument that Mexicans were prone to being infected with tuberculi

“enabled whites to view Mexicans as inherently weak, despite the arduous physical labor in which they engaged. And it contributed to the growing campaign to construct Mexicans as a racial group, not simply a national one.”

Racial weakness was also used to stigmatise Black Americans. In a statement released by the Tennessee State Medical Association in 1907, African Americans have ‘a poor hereditary foundation, one lacking in natural resistant qualities’. This was popularised by statistician and white supremacist Frederick Hoffman in his 1896 book Race Traits and Tendencies of the American Negro. His treatise contended that Black Americans were particularly susceptible to consumption. He argued that

“the root of the evil lies in the fact that an immense amount of immorality, which is a race trait, and of which scrofula, syphilis, and even consumption are the inevitable consequences…. It is not the conditions of life, but in the race traits and tendencies that we find the causes of the excessive mortality [emphasis in original].”

For vicious racists like Hoffman, this evolutionary weakness meant not only that African Americans would never be equal to whites, but that emancipation might be detrimental to Black communities.

Given such high levels of racism, classism, and general misanthropy, it is hardly surprising that the stigma associated by being exposed as consumptive was formidable – and not only for the person suffering the disease but for their entire family and immediate community. It was a disease of poverty and filth. In the words of Dr Woodcock of the National Association for the Prevention of Tuberculosis in 1912, ‘Tubercle is in truth a coarse common disease, bred in foul breath, in dirt, in squalor…. The beautiful and rich receive it from the unbeautiful poor…. Tubercule attacks failures’.

An example of the stigma associated with consumption can be taken from James Joyce’s Ireland. In the 1880s and 1890s, James Mooney, a member of the Smithsonian Institution’s Bureau of American Ethnology, collected Irish folklore. He was told the following story about TB:

“In Connemara, when one is dying of consumption it is customary to tie some unsalted butter in a piece of cloth and hang it up in the rafters. Just as the sick person is at his last gasp all of his blood relatives leav [sic] the hous [sic] and remain outside until he is dead. As he draws his last breath the contagion leavs [sic] his body and enters into one of his relatvs, [sic] should any be present, but finding none of them in the room, it goes up into the butter, which is then taken down and buried. In some parts of Galway this is said to keep off the disease only for a term of seven years. In asking how long the friends remained outside, my informant replied ‘They stay out til he’s dead – and wel [sic] dead’.”

These beliefs and rituals were relatively benign (although they did result in a lonely death). But other beliefs associated with consumption could be lethal. Consumptive symptoms might be interpreted as possession by fairies or becoming a changeling, for example. Notoriously, in 1895, this was the fate of a young woman called Bridget Cleary from Ballyvadlea (County Tipperary) who was burnt to death by her husband and neighbours when they mistook her TB symptoms as possession by fairies. The subsequent trial was important because it became emmeshed in debates about the ‘fitness’ of the Irish (particularly ‘superstitious’ rural folk) for Home Rule.

While the disjuncture between lay and scientific knowledge was not always so extreme, medical understandings about the transmission of the tubercule failed to dent the widespread assumption that the disease was hereditary. This was why the stigma of the disease attached to the entire family. Households could be thrown into financial ruin after employers dismissed all family members from their jobs, fearing contamination of their workplace. It was no surprise, then, that relatives sought to hide their medical history from employers, insurance companies, and even close friends and neighbours. Like the characters in James Joyce’s ‘The Dead’, they claimed to be suffering from a ’cold’; others blamed neurasthenia, an ill-defined nervous ailment that at least had the benefits of signalling a person’s delicate sensibilities. Physicians might collude with their patients’ wishes not to be branded with this stigmatising disease either out of compassion or self-protection (treating TB patients might reflect poorly on their professional standing).

High levels of fear and stigma made the disease ripe for unlicensed and often unscrupulous drug peddlers and health entrepreneurs, keen to make a ‘fast buck’ selling concoctions containing large quantities of alcohol and dyes, as well as remedies laced with poisonous levels of strychnine and lachnanthes (a hallucinogenic narcotic). In 1873, for example, desperate sufferers eagerly sought the ‘elixir of life’ or what one entrepreneur claimed was the ‘same kind of ointment as that which Mary Magdalen anointed the feet of Christ’. Given such a provenance was it any wonder the salve cost an exorbitant £60 (or 300 days wages for a skilled tradesman) for a full treatment? But unregistered medical entrepreneurs were increasingly joining up with others to share costs and advertise their cheap patent medicine to middle- and lower-middle class sufferers. As historian Barry Smith explained, these new clients were

“too proud to frequent out-patient wards, their working hours were too long to permit them to become regulars at dispensaries, they were too poor to pay for fashionable specialists and they were too fearful of losing their jobs and of their neighbours’ rejection to allow disclosure of their illness, while savings were too limited to allow them to enter a sanatorium as long-term patients.”

But Smith is also correct to draw attention to the fact that, although ‘quack physicians’ preyed on the vulnerabilities of desperately sick people, they also provided tuberculous patients with hope. They were selling comforting routines and rituals. Given that, until the 1920s, orthodox medicine had little to offer sufferers, bogus treatments might be as good as anything else on offer.

Indeed, practically all treatments were palliative. While infected women were expected to retreat inside their homes in order to continue fulfilling their domestic responsibilities, men were encouraged to take to the seas or emigrate to warmer climates, which were believed to help alleviate the symptoms of pulmonary TB. In the U.S. from the mid-nineteenth century, there was a regular procession of East Coast sufferers of TB migrating west, a journey that was made easier from 1869 with the completion of the transcontinental railroad. Such migrations were encouraged by the publication of ‘patient guidebooks’, with titles such as Winter Homes for Invalids. An Account of the Various Localities in Europe and America Suitable for Consumptives and Other Invalids (1875), New Mexico: Its Climatic Advantages for Consumptives (1883), California, for Fruit Growers and Consumptives (1883), and the (wonderfully alliterative!) The Canaries for Consumptives (1889).

It wasn’t until 1908 that effective medical responses for TB were made possible. This was when immunologists Albert Calmette and Camille Guérin, both based at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, used a diluted strain of bovine TB to create the vaccine BCG (Bacillus Calmette-Guérin). BCG was first administered to humans in 1922. The effect was dramatic. In Sweden, for example, by the mid-1930s, vaccinations resulted in a TB morality rate which was seven-times lower than a decade earlier.

However, while Canadian and most European physicians embarked on programmes of BCG vaccination, it was not popular in Britain and America, where physicians continued to rely on sanatoriums, hygiene education, and chemotherapy. Their reluctance was partly nationalistic (‘the French’) but there were also concerns about the vaccine’s safety and efficacy. British and American health professionals continued to emphasise the social causes of TB, which meant their energies were focussed on changing people’s behaviours.

Furthermore, there had been significant private and public investment in sanatoriums for consumptives. In the U.S., one of the first to open was Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium [sic] at Saranac Lake, established by Edward Livingston Trudeau (himself a TB sufferer: it was not uncommon for sanatoriums to be staffed by former consumptives) in 1885, just three years after Koch’s discovery of the tubercule bacillus. Their function was to provide clean, fresh air to ease breathing, to build up bodily strength, and to isolate infectious people so they would not spread the disease. They often prescribed a diet rich in fats and carbohydrates as well as hydrotherapy. Superintendents ran sanatoriums according to rigid, bureaucratic principles of science, rationality, and management. Some enforced rest and forbad risky activities such as reading and sex; while others (especially in Britain, with its revered ‘work ethic’) prescribed ‘work therapy’. For example, at the Frimley Sanitorium (a Hospital for Consumption and Diseases of the Chest, which opened in 1905), patients were expected to engage during daylight hours in strenuous gardening and construction work, before retiring to unheated, airy wards in the evenings.

Sanatoriums were largely preventive: by isolating infected people, the tuberculi would not be spread wider in the community. This was why they were supported by British prime Minister Lloyd George when he introduced the National Insurance Act of 1911, which provided financial assistance for local authorities opening sanatoria and free institutional treatment.

Sanatoriums were never going to be the solution for the epidemic of TB. They were not realistic options for many female sufferers, who were responsible for the care of their children and families. Sanatoriums were also often harsh places, where patients had to follow a strict regime. Although a few were attentive to the needs and preferences of patients, in others, patients were literally worked or frozen to death. In the 1920s, three quarters of patients died within five years of being institutionalised. Indeed, historian Barry Smith showed that the death rate of people discharged from sanatoria was no lower than among those treated in the community. In other words, the money spent on building and maintaining the sanatoriums could have been better spent improving the living conditions of the labouring poor.

The fact that they provided accommodation for only around two per cent of active suffers in Britain means that they could not have been a major driving force in the decline of the disease. More commonly, sick people isolated themselves at homes, sleeping on porches, in tents, in the back garden, or in designated ‘sick rooms’. Those able to afford it built verandas for sleeping. These architectural innovations, however, had the unfortunate effect of disclosing ‘respiratory problems in a family as clearly as if a marching band had been hired to announce it’, as Katherine Orr explains in Fevered Lives: Tuberculosis in American Culture Since 1870. These were not realistic options for sufferers in the densely populated tenements of the major cities.

Surgery was also an option. In the days of ‘heroic surgery’ (peaking in the 1930s), TB-infected lungs could be subjected to procedures such as pneumothorax (collapsing a lung by injecting it with oxygen or nitrogen), thoracoplasty (removing ribs from the chest wall), lobectomy (excising one of the lobs of the lung), and pneumonectomy (taking out one lung altogether).

In the first three decades of the twentieth century, surgeons and other medical professionals who believed that TB was transmissible from mother to foetus (a belief that persisted within medical circles well into the twentieth century) resorted to sterilizing consumptive women. While almost no-one sterilizing male invalids – even though it was a much simpler and safer operation – medical reservations about the biological ‘normality’ of pregnancy (in the words of cardiologist Louis Levin in 1935, ‘pregnancy at its best is an additional burden on the entire organism’) meant that sterilising female consumptives had many advocates. The sterilization of women was made safer by the invention of aseptic technique of surgery in the last decades of the nineteenth century. These safer surgical practices increased the willingness of both doctors and their patients to undergo increasingly invasive surgical procedures. The fact that more women were giving birth in hospitals also played a part since it provided an opportunity for physicians to sterilize TB-infected women immediately after they had given birth. Part of the rationale given by physicians was their anxiety about the physiological strain of parturition for women with pre-existing conditions such as TB and heart disease. However, this laudable desire to reduce maternal death rates coincided with less admirable eugenic concerns. One example of a physician who was concerned both with women’s health and eugenics was Adolphus Knopf, a physician working in the Riverside Hospital-Sanatorium for the Consumptive Poor in New York City. In a 1917 edition of the American Journal of Public Health, he maintained that the children of tubercular parents had ‘lessened vitality’, having inherited a ‘physiological poverty’. He was saddened by the ‘tears and suffering’ of mothers faced with a ‘puny babe destined to disease, poverty, and misery’. In a subsequent article entitled ‘The Family Doctor and Birth Control’ (1931), he made his eugenic motivations even clearer. Once again, he began by emphasizing his sympathy for pregnant women, stating as a fact that ‘pregnancy has a definitely deleterious effect on tuberculous women…. Even a slight tuberculous condition becomes serious disease and often ends fatally’. But this was followed by his argument that allowing such women to have children was leading to ‘the deterioration of our population’. He contended that there was ‘one remedy, namely sterilization of the hopelessly defective’. He urged every medical school in the country to teach doctors the basis of ‘legal sterilization and all that is known of hereditary disease and eugenics’. A decade later, such views continued to be espoused. For example, in the 1927 edition of the Medical Record (a journal based in New York), Harald Samson-Himmelstjerna bullishly maintained that ‘Nature shows us that tuberculous individuals should not be allowed to propagate, and the state should have the right to force tuberculous persons to be sterilized in the interests of the future of the race’. The ‘white race’ had to be protected from desperately ill women.

Sterilization was a preventive measure. Two other preventive measures dominated discussions: the first was stamping out the source of TB in infected food; the second, hygiene education. By the 1880s, there was clear scientific evidence that two of the main vectors of the disease were diseased meat and milk. From the 1860s onwards, there had been a dramatic rise in the consumption of meat in Britain and the U.S. According to one estimate, meat consumption in Britain almost doubled between the 1860s and the 1890s: it had increased further by 1914. Rising real incomes, coinciding with the falling prices of foodstuffs – due, in part, to improved agricultural productivity and dramatic reductions in the cost of transporting products from farms to towns and cities – meant that consumers could afford to buy and consume more meat. Meat-eating was also promoted by nineteenth century reformers, who forecast remarkable transformations in the productivity of working men and women if meat was to become a significant part of their diets.

The problem was that much of the meat working-class people could afford to purchase was infected with TB. The risks of such meat had been recognized by the burgeoning disciplines of veterinary medicine and comparative pathology since the late nineteenth century. In 1882, German bacteriologist Robert Koch proved what had long been suspected: that bovine and human tuberculosis were caused by the same organism. At the Brown Animal Sanatory Institution (a London-based institute for veterinary research) in 1884, the leading British bacteriologist Edward Klein was able to demonstrate that animals who were fed with infected meat developed TB. It was a finding that was replicated by numerous other scientists so that, by the 1890s, ‘bovine tuberculosis had become the paradigm zoonosis’, according to historian Keir Waddington. As one butcher admitted in the 1890s, poor families were being sold meat that was “possible a shade above carrion, but very little”. Tubercular milk quickly joined meat as a major source of concern. The meat and milk trades responded by agreeing to inspection of slaughterhouses and the pasteurization of milk. They continued to insist, however, that any tuberculi infection was limited to the immediate area of inflammation rather than being dispersed throughout the animal. In this, they were wrong.

The second major response was hygiene education. Local and national authorities instigated major campaigns in cleanliness and sanitation. For example, in the U.S. during the so-called ‘Progressive Era’ (that is, the 1890s to 1920s), officials tackled such things as ‘promiscuous spitting’, believing that the main cause of the spread of disease was the spread of infected sputum. Sufferers were required to always carry an ‘expectoration bottle’. Commonplace human activities such as kissing became bacteriological dangers – not only did kissing spread germs but it lured people into morally and medically unsafe environments where more than the TB bacterium could be spread. These places were morally dangerous: dispersing syphilis and alcoholism as easily as tuberculosis.

These campaigns and medical interventions have been controversial. This is not surprising since they were never only about disease. Major concerns included the policing of working class and immigrant communities, as well as fostering middle-class behaviour. There is also disagreement amongst historians about the efficacy of the campaigns. After all, by the time they were instigated, TB was already declining. Historians such as Michael E. Teller in The Tuberculosis Movement: A Public Health Campaign in the Progressive Era (1988), want to reclaim their value. He insists that the combined reforms and movements activated by physicians, voluntary societies, and public agencies produced positive results. At the very least, they provided support for ailing individuals while laying a basis for mass x-ray screening programmes. Teller cites one worker in 1912 who contended that anti-TB initiatives were

“forcing radical changes and improvements in schools, in housing conditions, in workshops and factories, in prisons and reformatories, in child-labor, in healthful recreation, and in most of the many organized efforts of recent growth for mutual protection and betterment.”

Medicine alone is also insufficient. After all, by the time the effective treatment of streptomycin was available, TB already accounted for less than five per cent of all deaths. None of the campaigns, vaccination programmes, and treatments sought to address the underlying cause of disease, which were rooted in social and economic inequalities.

Finally, let’s return to the question asked at the start of this talk: what can a cultural history of TB contribute to debates today? It reminds us that culture gives meaning to nature. The meanings given to TB shaped the way sufferers experienced the disease and responded to it in their lives. A painful world is still a world of meaning. The sufferings of creative geniuses were no less distressing because they could frame their dying in romantic ways. The stigma attached to being consumed by the tubercule bacilli was immeasurably worse for minoritized and marginalized people – but they, too, sought ways of coping drawn from their specific times and places. The self-fashioning process is culture-bound: both located within the corporeal body and enclosed by everything without, including environment, language, and relationships. History also helps by reminding us that controlling and eradicating disease is not simply a medical issue. It is about politics, ideology, and economics – or, colonialist economic exploitation, population dislocation, and gross levels of inequality. Solutions to suffering must be found at macro levels – that is, attempts to reduced huge wealth disparities such as debt relief. But this requires a shift in focus from disease to health. Are we prepared to make the financial, political, and cultural investments that would be required?

© Professor Bourke 2022

References and Further Reading

Abel, Emily K., ‘From Exclusion to Expulsion: Mexicans and Tuberculosis Control in Los Angeles, 1914-1940’, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 77.4 (winter 2003)

Bourke, Joanna, Disgrace: Global Reflections on Sexual Violence (London, 2022)

Bourke, Joanna, The Story of Pain: From Prayer to Pain Killers (Oxford, 2014)

Bourke, Joanna, What It Means To Be Human (London, 2011)

Bryder, Linda, Below the Magic Mountain: A Social History of Tuberculosis in Twentieth Century Britain (Oxford, 1988)

Jones, David S., ‘Virgin Soils Revisited’, The William and Mary Quarterly, 60.4 (October 2003)

Lawlor, Clark, Consumption and Literature: The Making of a Romantic Disease (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006)

McMillen,Christian W., Discovering Tuberculosis: A Global History, 1900 to the Present (New Haven, 2015)

McMillan, Christian W., ‘”The Red Man and the White Plague”: Rethinking Race, Tuberculosis, and American Indians, ca. 1890-1950’, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 82.3 (Fall 2008)

Myers, J. Arthur, ‘Development of Knowledge of Unity of Tuberculosis and of the Portal of Entry of Tubercule Bacilli’, Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 29.12 (April 1974)

Orr, Katherine, Fevered Lives: Tuberculosis in American Culture Since 1870 (Cambridge, Mass., 1996)

Smith, Barry, ‘Gullible’s Travails: Tuberculosis and Quackery 1890-1930’, Journal of Contemporary History, 20.4 (October 1985)

Waddington, Keir, The Bovine Scourge. Meat, Tuberculosis, and Public Health, 1850-1914 (Woodbridge, 2006)

References and Further Reading

Abel, Emily K., ‘From Exclusion to Expulsion: Mexicans and Tuberculosis Control in Los Angeles, 1914-1940’, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 77.4 (winter 2003)

Bourke, Joanna, Disgrace: Global Reflections on Sexual Violence (London, 2022)

Bourke, Joanna, The Story of Pain: From Prayer to Pain Killers (Oxford, 2014)

Bourke, Joanna, What It Means To Be Human (London, 2011)

Bryder, Linda, Below the Magic Mountain: A Social History of Tuberculosis in Twentieth Century Britain (Oxford, 1988)

Jones, David S., ‘Virgin Soils Revisited’, The William and Mary Quarterly, 60.4 (October 2003)

Lawlor, Clark, Consumption and Literature: The Making of a Romantic Disease (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006)

McMillen,Christian W., Discovering Tuberculosis: A Global History, 1900 to the Present (New Haven, 2015)

McMillan, Christian W., ‘”The Red Man and the White Plague”: Rethinking Race, Tuberculosis, and American Indians, ca. 1890-1950’, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 82.3 (Fall 2008)

Myers, J. Arthur, ‘Development of Knowledge of Unity of Tuberculosis and of the Portal of Entry of Tubercule Bacilli’, Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 29.12 (April 1974)

Orr, Katherine, Fevered Lives: Tuberculosis in American Culture Since 1870 (Cambridge, Mass., 1996)

Smith, Barry, ‘Gullible’s Travails: Tuberculosis and Quackery 1890-1930’, Journal of Contemporary History, 20.4 (October 1985)

Waddington, Keir, The Bovine Scourge. Meat, Tuberculosis, and Public Health, 1850-1914 (Woodbridge, 2006)

Part of:

This event was on Thu, 06 Oct 2022

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham College plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login