Unwrapping Irving Berlin’s "White Christmas"

Share

- Details

- Text

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

This festive lecture explores the unusual roots of the song ‘White Christmas’ and its role in establishing the concept of the commercial Christmas song. It explains how the song’s release during the summer months hints at how its potential as an enduring seasonal classic was not anticipated, and then examine how the music and lyrics helped it to resonate in a time of war. The lecture also considers Berlin’s patriotism and his active role in the Second World War.

Professor Broomfield-McHugh is joined by actress Beverley Klein in live performances of songs by Irving Berlin.

Download Text

Showstoppers: Unwrapping Irving Berlin’s ‘White Christmas’

Dominic Broomfield-McHugh, Visiting Professor of Film and Theatre Music

12 December 2024

Dreaming of a White Christmas in Eisenhower’s America

In this lecture, I will consider the curious historical intersection of America’s most successful Christmas song with the political career of a war veteran. While Donald J. Trump’s three attempts to become President of the United States of America drew the wrath of a plethora of popular singers who objected to his use of their music in his campaigns, in the 1950s Irving Berlin took part in a movement to persuade General Dwight D. Eisenhower – the architect of the Normandy landings – to run for office, even writing a song about it that became his campaign song. Following Eisenhower’s election to the Oval Office in the 1952 presidential election, Berlin captured the spirit of the former General in the movie White Christmas, which opened in 1954: the opening scene shows a general sitting among his troops watching Bing Crosby’s character perform ‘White Christmas’, and the rest of the film depicts Crosby’s post-war attempts to help the retired General in civilian life. The lecture looks at how and why Berlin might have wanted to use his sentimental Christmas hit in this way.

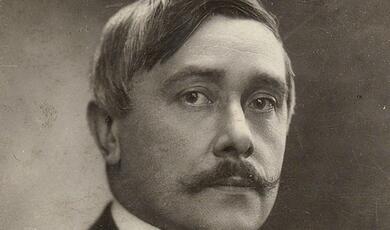

‘Irving Berlin is American Music'

Irving Berlin’s career typifies the American dream: he was born in Siberia, came to America aged 5 without knowing a word of English, and ended up being known as one of America’s greatest songwriters. Indeed, his fellow composer Jerome Kern famously remarked: ‘Irving Berlin has no place in American music – he is American music.’ How did he achieve this?

One reason is that he was simply so productive, writing over 1200 published songs and several hundred more that never saw the light of day. In the middle of his career in particular, he had the ability to write almost one hit a year, with stand-outs including ‘Blue Skies’ (1926), ‘Puttin’ on the Ritz’ (1929), ‘How Deep is the Ocean’ (1932), ‘Easter Parade’ (1933), ‘Cheek to Cheek’ (1935), ‘Let’s Face the Music and Dance’ (1936), and the holiday song ‘I’ve Got My Love to Keep Me Warm’ (1937). His mastery of the English language and versatility as a composer combined to serve his insights into the American experience, rendering him a special favourite of the nation.

He affected the landscape of Broadway, co-owning a specially-built theatre, the Music Box, for which he wrote a series of special shows: the Music Box Revues. Berlin himself appeared in the inaugural edition, in a spoofy autobiographical number in which he was interviewed by eight chorus girls known as the Eight Little Notes. He also had special clout in Hollywood: according to the scholar Peter Evans, for Top Hat Berlin was paid $75,000 for providing the five songs that were used in the movie, retaining the publication rights in them, versus the stars Fred Astaire ($40,000) and Ginger Rogers ($7,172.50).

Holiday Inn

By 1939, Berlin had a unique place at the heart of American life, and he came up with the idea of writing a revue or variety show based on the main American public holidays. Happy Holiday was to feature one song per holiday, ranging from New Year to Valentine’s Day to Easter to Veteran’s Day, and the first draft in the Library of Congress’s Irving Berlin collection (reproduced in the lecture with thanks to the Berlin estate) is dated February 1939. He seems to have worked on the project on and off through that year, and on the weekend of 6 and 7 January 1940 he completed the words and music for the song we’re discussing tonight, ‘White Christmas’. On Monday 8 January, he entered his office at Irving Berlin Music (his own publishing business) and his musical secretary wrote down the melody that Berlin dictated to him; the words were also typed out and dated that day. (Berlin himself couldn’t read or write music very well.)

By April 1941, the project had been reconceived as a film, and it was no longer a revue: it was now a star vehicle for Bing Crosby and Fred Astaire, a former double act who break up when Crosby’s character decides to retire and open an inn that only opens on the public holidays. This neatly used up the sixteen songs Berlin had conceived for the project. Holiday Inn, as it was now called, opened on 4 August 1942 at the Paramount in New York City, and became the sixth highest grossing film of the year.

Yet because the movie that gave birth to ‘White Christmas’ opened in the summer, the studio decided not to promote that song initially, even though Bing Crosby’s recording of it had been released with five others on July 30. Instead, they promoted the Valentine’s Day song ‘Be Careful, It’s My Heart’ (which we’ll hear in the lecture itself) and the Billboard charts show how that number got the highest number of radio plugs of any song in the country on the week of the film’s release. By the week of 22 October 1942, ‘White Christmas’ had become both the bestselling sheet music in America and the bestselling record (in Crosby’s version).

What happened? By the middle of the autumn, the impact of the Second World War on America had made ‘White Christmas’ resonate with the American public, now ten months after the Pearl Harbor attack. A famous article by Carl Sandburg in the Chicago Times summarised the song’s emotional impact:

‘We have learned to be a little sad and a little lonesome without being sickly about it. This feeling is caught in the song of a thousand juke boxes and the tune whistled in streets and homes, ‘I’m Dreaming of a White Christmas’. When we sing that we don’t hate anybody. And there are things we love that we’re going to have sometime if the breaks are not too bad against us. Way down under this latest hit of his Irving Berlin catches us where we love peace.’

Carl Sandburg, Chicago Times, December 1942

Berlin anticipated Sandburg’s reaction in a letter to the film’s director Mark Sandrich from November, in which he revealed that the sheet music of ‘White Christmas’ was selling over 90,000 copies per week. It was the biggest hit of his career, and he commented to Sandrich that ‘it can be applied to the world situation as it exists today. I understand many copies are being sent to the boys overseas, and it is just possible that while it isn’t a war song, it can easily be associated with it.’

Berlin’s patriotism

The letter also refers to the success of a second Irving Berlin musical that opened in the summer of 1942: the stage musical This is the Army, which was written for, produced by, and performed by the US Army, in aid of the Army Emergency Relief Fund. Berlin was a patriot, which is the other reason Kern’s comment that Berlin was American music particularly resonated: he wrote, for example, the song ‘God Bless America’, which was performed on the radio at an emotional moment for the nation in 1938 by pop singer Kate Smith and came to be a kind of alternative national anthem, performed memorably by Celine Dion after 9/11. Along with various special songs written by Berlin for the armed forces, This is the Army solidified his reputation as an artist with a special investment in nationhood. A number from the score provides a window into why ‘White Christmas’ landed so well with the zeitgeist: ‘I’m Getting Tired so I Can Sleep’ contains the line ‘I want to dream so I can be with you’, depicting how a soldier parted from his loved one has to use dreams to be transported to another place and time; the same sentiment is expressed in ‘White Christmas’.

During the London run of This is the Army (which travelled across the world), Berlin encountered General Eisenhower for the first time. The General was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in Europe, and he visited the cast of This is the Army at Her Majesty’s Theatre, giving them a moving speech that Berlin recalled seven years later in a letter to the General: ‘I have never forgotten the first time I met you in London when you came to see “This is the Army” and that inspiring talk that you gave to the boys backstage.’ After being made into a film, This is the Army continued to generate money for the Relief Fund, totaling about $12 million. In October 1946, Berlin was awarded the Roosevelt Medal for Distinguished Services, alongside Eisenhower, whom he encountered again.

Eisenhower the Reluctant Politician: The Musical

In the summer of 1947, incumbent President Harry Truman approached Eisenhower with an offer: if Eisenhower would run for the Democrats in the 1948 Presidential election, Truman would run as Vice President. Truman had been Roosevelt’s Vice President until the latter’s death in office in 1945, and he was reluctant to remain in the role. He documented his discussion with Eisenhower in his diaries, which are reproduced on the Truman Presidential Library website. But Eisenhower turned him down, as he had done when others had previously suggested he would make a good presidential candidate. Things heated up in September 1947 when the Washington Post ran a poll showing that Eisenhower would beat Truman if they ran against each other in 1948 but the General continued to resist, seeing his military career as something that needed to be kept out of politics. Ironically, his lack of interest in party politics is what made him a popular candidate.

All of this inspired Berlin to write Stars on my Shoulders, a musical about a retired general who is persuaded to run for President. By January 1948, Berlin had worked out a synopsis and started to write some songs; the book was to be by Norman Krasna, and Rodgers and Hammerstein were set to produce. The press started to cover the project, but in April it was suddenly pulled because Krasna wanted an excessive stake in the production as an investor. The newspapers also suggested that the political content was problematic given its proximity to the 1948 general election.

Call Me Madam and Eisenhower for President

Undeterred, Berlin moved on, and in 1949 he started work on another political musical based on real life. He was open to the press about basing Call Me Madam (1950) on Perle Mesta, a Washington socialite who’d become American Ambassador to Luxembourg, holding the role from 1949-53. The published script humorously declared: ‘The play is laid in two mythical countries. One is called Lichtenburg, the other the United States of America.’

In the second act of the show, Berlin once more turned to Eisenhower for inspiration. Truman had unexpectedly won the 1948 election but by 1950 he had become unpopular, and Berlin decided to reflect the mood of many in the public in a song called ‘They Like Ike’, in which a Republican and two Democrats discuss how Eisenhower was an appealing alternative to Truman because he said he didn’t want to become President.

The musical opened on 12 October 1950 and four days later the headline of the New York Times declared that the Republican frontrunner, Governor Dewey of New York, intended to step down from the 1952 election and backed Eisenhower to run instead – even though Eisenhower himself still had no intention of entering politics. At this point, Eisenhower was President of Columbia University, and he attended the opening of Call Me Madam despite rarely going to the theatre.

Six days later, Berlin wrote directly to Eisenhower, thanking him for coming, and saying how much he was glad that the ‘Ike’ song was landing so well with the public. Both onstage and off, Berlin was agitating for Eisenhower to run for the highest office in the land.

As for Eisenhower, he took a leave of absence and became Supreme Commander of NATO, and continued to resist the political project throughout 1951, including when the Democratic incumbent Truman encouraged him to run as a Republican in 1952. Such was Eisenhower’s position in the American consciousness.

White Christmas and General Waverley

Around this time, Berlin and Paramount revived the idea behind Stars on My Shoulders as a film, this time focusing on the efforts of two successful performers played by Bing Crosby and Danny Kaye to help their former unit commander, General Thomas Waverly, to thrive as the owner of an inn after his retirement from the army; he feels forgotten. Songs from the abandoned show were repurposed: ‘Gee, I Wish I Was Back in the Army’, ‘What Do You Do With a General?’ and ‘The Old Man’ were fitted into the new plot. Berlin also took a song cut from Call Me Madam, ‘Free’, and gave it new words to become ‘Snow’.

Yet the iconic performance of ‘White Christmas’ that opens the film dramatizes the unusual cultural resonance that the song had during the Second World War and marks the special admiration Berlin had for Eisenhower as a result of his encounter with him during the run of This is the Army. Waverly is the first character we see in the film, and now we can understand why this beloved seasonal film contains an apparently bewildering military streak running through its core: Waverly represents Berlin’s hero, Eisenhower.

© Professor Dominic Broomfield-McHugh 2024

Further reading:

Christian G. Appy, ‘Sentimental Popular Films’ in Peter J. Kuznick and James Gilbert (eds.), Rethinking Cold War Culture, Smithsonian Books, 2001, pp.74-105.

Mary Ellin Barrett, Irving Berlin: A Daughter’s Memoir, Simon and Schuster, 1994.

Laurence Bergreen, As Thousands Cheer: The Life of Irving Berlin, Hodder and Stoughton, 1990.

David Haven Blake, Liking Ike: Eisenhower, Advertising, and the Rise of Celebrity Politics, Oxford University Press, 2016.

Peter Evans, Top Hat, Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

Michael Freedland, A Salute to Irving Berlin, W. H. Allen, 1986.

Philip Furia, Irving Berlin: A Life in Song, Schirmer, 1998.

James Kaplan, Irving Berlin: New York Genius, Yale University Press, 2019.

Robert Kimball and Linda Emmet, The Complete Lyrics of Irving Berlin, Applause 2005.

Jeffrey Magee, Irving Berlin’s American Musical Theatre, Oxford University Press, 2012.

Jody Rosen, White Christmas: The Story of a Song, Fourth Estate, 2002.

Benjamin Sears, The Irving Berlin Reader, Oxford University Press, 2012.

Primary Sources

All manuscripts shown in the lecture reproduced from the Irving Berlin collection at the Library of Congres by permission of the Estate of Irving Berlin, which holds the copyright.

Filmography

Holiday Inn, 1942

White Christmas, 1954

© Professor Dominic Broomfield-McHugh 2024

Christian G. Appy, ‘Sentimental Popular Films’ in Peter J. Kuznick and James Gilbert (eds.), Rethinking Cold War Culture, Smithsonian Books, 2001, pp.74-105.

Mary Ellin Barrett, Irving Berlin: A Daughter’s Memoir, Simon and Schuster, 1994.

Laurence Bergreen, As Thousands Cheer: The Life of Irving Berlin, Hodder and Stoughton, 1990.

David Haven Blake, Liking Ike: Eisenhower, Advertising, and the Rise of Celebrity Politics, Oxford University Press, 2016.

Peter Evans, Top Hat, Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

Michael Freedland, A Salute to Irving Berlin, W. H. Allen, 1986.

Philip Furia, Irving Berlin: A Life in Song, Schirmer, 1998.

James Kaplan, Irving Berlin: New York Genius, Yale University Press, 2019.

Robert Kimball and Linda Emmet, The Complete Lyrics of Irving Berlin, Applause 2005.

Jeffrey Magee, Irving Berlin’s American Musical Theatre, Oxford University Press, 2012.

Jody Rosen, White Christmas: The Story of a Song, Fourth Estate, 2002.

Benjamin Sears, The Irving Berlin Reader, Oxford University Press, 2012.

Primary Sources

All manuscripts shown in the lecture reproduced from the Irving Berlin collection at the Library of Congres by permission of the Estate of Irving Berlin, which holds the copyright.

Filmography

Holiday Inn, 1942

White Christmas, 1954

Part of:

This event was on Thu, 12 Dec 2024

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham College plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login