Adultery in the Novel, from Flaubert to Sally Rooney

Share

- Details

- Transcript

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

Adultery became the subject of some of the greatest European novels of the nineteenth century, including Madame Bovary and Anna Karenina. English novels of the period needed adultery for their plots, yet flinched from treating the subject openly.

Through the twentieth century to the present – from Ulysses and A Handful of Dust to recent fiction by Zadie Smith, Tessa Hadley and Sally Rooney – adultery has fascinated novelists. Why is this? And do male and female authors treat adultery differently?

Download Transcript

Adultery in the Novel

Professor John Mullan

26th October 2022

Novelists still need adultery, it seems. Here is a passage from Sally Rooney’s debut novel, Conversations with Friends, first published in 2017. Frances, our narrator, is a 21-year-old university student in Dublin. She and her friend Bobbi have come to know a sophisticated married couple in their thirties, Nick and Melissa. Nick is an actor; Melissa a successful writer and photographer. They welcome them into their home and their lives. Frances finds Nick increasingly attractive and, at Melissa’s bibulous birthday party, in the utility room, by the fridge, she kisses him. They send each other a few flirtatious emails. The following week, Frances knows that Melissa is away working in London. She goes back to the house

I told him I didn’t want to be a homewrecker or whatever. He laughed at that.

That’s funny, he said. What does that mean?

I mean, you’ve never had an affair before. I don’t want to wreck your marriage.

Oh, well, the marriage has actually survived several affairs, I just haven’t been involved in any of them.

He said this amusingly, and it made me laugh, though it also had the effect, which I guess was intended, of making me relax about the morality side of things. I hadn’t really wanted to feel sympathetic to Melissa, and now I felt her moving outside my frame of sympathy entirely, as if she belonged to a different story with different characters.

Sally Rooney, Conversations with Friends (2017), Ch. 9

Note how the effects here depend on that technique of refusing to mark off speech from narration: no quotation marks. As if all dialogue is absorbed into her perceptions and her story.

We are to notice the easy evasion that comes with her odd phrase, ‘the morality side of things’ – though Rooney has stacked the cards by having Nick tell Frances that his wife has already had unspecified affairs.

Of course, we never get the word ‘adultery’ in this novel. But here we get the echo of an old prohibition.

Characteristically, Melissa’s sentiments are finally revealed (or at least stated) in a very long email late in the novel, once she has found out about her husband’s adultery. No room for dialogue or argument - not much chance of Frances being affected (she muses dispassionately on how the email might have been edited).

Nick’s married condition gives Frances’s affair with him its electricity – makes it compulsive, risky, ill-advised, adventurous.

Why do we hardly use the word ‘adultery’ (or ‘adulterer’, let alone ‘adulteress’) any more? Melissa, Sally Rooney’s wronged wife, would not dream of using it.

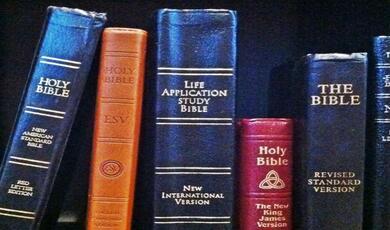

Perhaps because ‘adultery’ used to be a word for a sin – an offence against God.

Here is Defoe’s Moll Flanders being very hard upon herself.

I never was in Bed with my Husband but I wish’d myself in the Arms of his Brother; and tho’ his Brother never offer’d me the least Kindness that way after our Marriage, but carried it just as a Brother ought to do; yet ,it was impossible for me to do so to him: In short, I committed Adultery and Incest with him every Day in my Desires, which, without doubt, was as effectually Criminal in the Nature of the Guilt, as if I had actually done it.

Daniel Defoe, Moll Flanders (1722 )

(Incest because intercourse between a man and his brother’s wife is forbidden in Leviticus, and thence in the Book of Common Prayer.) We probably all know about the Seventh Commandment, ‘Thou shalt not commit adultery’, but perhaps not the passage in Deuteronomy that specifies the proper punishment.

If a man be found lying with a woman married to an husband, then they shall both of them die, both the man that lay with the woman, and the woman: so shalt thou put away evil from Israel.

Deuteronomy, 22. 22

Yet there is a Christian tradition of adultery as the forgivable sin.

2 And early in the morning he came again into the temple, and all the people came unto him; and he sat down, and taught them.

3 And the scribes and Pharisees brought unto him a woman taken in adultery; and when they had set her in the midst,

4 They say unto him, Master, this woman was taken in adultery, in the very act.

5 Now Moses in the law commanded us, that such should be stoned: but what sayest thou?

6 This they said, tempting him, that they might have to accuse him. But Jesus stooped down, and with his finger wrote on the ground, as though he heard them not.

John, 8. 2-6

7 So when they continued asking him, he lifted up himself, and said unto them, He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her.

8 And again he stooped down, and wrote on the ground.

9 And they which heard it, being convicted by their own conscience, went out one by one, beginning at the eldest, even unto the last: and Jesus was left alone, and the woman standing in the midst.

10 When Jesus had lifted up himself, and saw none but the woman, he said unto her, Woman, where are those thine accusers? hath no man condemned thee?

11 She said, No man, Lord. And Jesus said unto her, Neither do I condemn thee: go, and sin no more.

John, 8. 7-11

Here is Rembrandt’s famous version of the moment when the woman is produced to test Jesus.

Novelists are almost forced to think of adultery as forgivable – at least, explicable – because imagining the road to adultery becomes, in the nineteenth century, one powerful way of writing about marriage. The author of the richest book on the subject thinks that marriage is the essential subject of the novel.

The bourgeois novelist has no choice but to engage the subject of marriage in one way or another, at no matter what extreme of celebration or contestation. He may concentrate on what makes for marriage and leads up to it, or on what threatens marriage and portends in disintegration, but his subject will still be marriage.

Tony Tanner, Adultery in the Novel, p. 15.

Adultery happens when you have married the wrong person.

Jane Austen does not, of course, take us inside an adulterous relationship, but in one way her version of the sin is characteristically audacious. In Mansfield Park, Maria Bertram marries Mr Rushworth because she despises him. She has been jilted by Henry Crawford, with whom, during play rehearsals, she conducted a high intensity flirtation – right in front of her fiancé. Now Crawford has carelessly dropped her and gone off to amuse himself in Bath. She will show him.

On his return from Antigua, her father, Sir Thomas, perceives that Mr Rushworth is a very poor specimen: ‘an inferior young man, as ignorant in business as in books, with opinions in general unfixed, and without seeming much aware of it himself’. Neither can he deceive himself ablout ‘her feelings’: ‘Little observation there was necessary to tell him that indifference was the most favourable state they could be in. Her behaviour to Mr. Rushworth was careless and cold. She could not, did not like him’. It is all pretty clear.

Convention forbids a man who has proposed marriage from backing out, but a woman is allowed to change her mind.

With solemn kindness Sir Thomas addressed her: told her his fears, inquired into her wishes, entreated her to be open and sincere, and assured her that every inconvenience should be braved, and the connexion entirely given up, if she felt herself unhappy in the prospect of it. He would act for her and release her. Maria had a moment’s struggle as she listened, and only a moment’s: when her father ceased, she was able to give her answer immediately, decidedly, and with no apparent agitation. She thanked him for his great attention, his paternal kindness, but he was quite mistaken in supposing she had the smallest desire of breaking through her engagement, or was sensible of any change of opinion or inclination since her forming it. She had the highest esteem for Mr. Rushworth’s character and disposition, and could not have a doubt of her happiness with him.

Jane Austen, Mansfield Park (1814) Vol. II, Ch.III

As ever, Jane Austen is pioneering in representing the lead up to and the consequences of adultery, in Mansfield Park. Reckoning up the consequences of Maria Rushworth’s affair with Henry Crawford, she asks us to face up to the double standard.

That punishment, the public punishment of disgrace, should in a just measure attend his share of the offence is, we know, not one of the barriers which society gives to virtue. In this world the penalty is less equal than could be wished; but without presuming to look forward to a juster appointment hereafter, we may fairly consider a man of sense, like Henry Crawford, to be providing for himself no small portion of vexation and regret: vexation that must rise sometimes to self-reproach, and regret to wretchedness, in having so requited hospitality, so injured family peace, so forfeited his best, most estimable, and endeared acquaintance, and so lost the woman whom he had rationally as well as passionately loved.

Mansfield Park,

Henry Crawford, of course, is not an adulterer. No more are either of Emma Bovary’s lovers, Rodolphe and Léon in Flaubert’s Madame Bovary. Or Anne Karenina’s lover …

I would say that it is easy to think of novels about female adultery, but not so easy to think of novels (like Sally Rooney’s) featuring male adulterers. Why is this?

Those who commit adultery in nineteenth-century fiction belong to a world where divorce was either not possible, or very, very difficult.

Liberal divorce laws may have been good for society, but they were a disaster for the English novel. How much more interesting for novelists when a woman’s decision to marry could not be reversed or corrected.

One campaigner for liberalisation of laws on divorce was that unhappily married novelist, Charles Dickens. In Hard Times, he has the factory worker Stephen Blackpool married to a baleful, drunken wife, who no longer lives with him, but still haunts him. He is hopelessly in love with Rachael, his fellow worker. He has this desperate conversation with the appalling Bounderby about the impossibility of divorce.

Mine’s a grievous case, an’ I want—if yo will be so good—t’ know the law that helps me.’

‘Now, I tell you what!’ said Mr. Bounderby, putting his hands in his pockets. ‘There is such a law.’

Stephen, subsiding into his quiet manner, and never wandering in his attention, gave a nod.

‘But it’s not for you at all. It costs money. It costs a mint of money.’

‘How much might that be?’ Stephen calmly asked.

‘Why, you’d have to go to Doctors’ Commons with a suit, and you’d have to go to a court of Common Law with a suit, and you’d have to go to the House of Lords with a suit, and you’d have to get an Act of Parliament to enable you to marry again, and it would cost you (if it was a case of very plain sailing), I suppose from a thousand to fifteen hundred pound,’ said Mr. Bounderby. ‘Perhaps twice the money.’

‘There’s no other law?’

‘Certainly not.’

Charles Dickens, Hard Times (1854), Book the First, XI

He does not, of course, commit adultery (though Dickens did). Instead, he dies.

The 1857 Matrimonial Causes Act (brought in the year before Dickens separated from his wife, Catherine) introduced divorce through the court. Men were able to “petition the court” for a divorce on the basis of their wife’s adultery, which would have to be proved, as would the absence of any collusion or condonation of that adultery. Women who wanted to divorce their husbands needed also to prove an aggravating factor of the adultery, such as rape or incest. The High Court in London was the only place to get your divorce, and proceedings were held in open court, enabling society to be scandalised by the personal details revealed during the process. But it was some kind of liberalisation.

The very next year, the painter Augustus Egg exhibited a triptych of scenes that might as well have been labelled ‘adultery and its consequences’.

[see image]

Matching the sentiment-arousing intent of this painting was the sensational bestseller of three years later, Mrs Henry Wood’s East Lynne.

The impecunious but beautiful Lady Isabel Vane marries the kindly lawyer Archibald Carlyle who buys her former home, East Lynne. She is made miserable in her marriage by the interference of her husband’s sister, Cornelia, who resents the marriage – and by her growing (but unfounded) conviction that her husband is romantically involved with a local lady, Barbara Hare. This misconception is encouraged by the rakish Captain Francis Levison, with whom she elopes. When she has disappeared, the servant, Joyce, knows immediately what has happened, but the husband is mystified – until he sees the letter.

Though a calm man, one who had his emotions under his own control, he was no stoic, and his fingers shook as he broke the seal.

“When years go on, and my children ask where their mother is, and why she left them, tell them that you, their father, goaded her to it. If they inquire what she is, tell them, also, if you so will; but tell them, at the same time, that you outraged and betrayed her, driving her to the very depth of desperation ere she quitted them in her despair.”

The handwriting, his wife’s, swam before the eyes of Mr. Carlyle. All, save the disgraceful fact that she had flown—and a horrible suspicion began to dawn upon him, with whom—was totally incomprehensible. How had he outraged her? In what manner had he goaded her to it. The discomforts alluded to by Joyce, and the work of his sister, had evidently no part in this; yet what had he done? He read the letter again, more slowly. No he could not comprehend it; he had not the clue.

Mrs. Henry Wood, East Lynne (1861), Ch. XXIV

Her husband has a sterner code, when, once he has been granted a divorce, he is asked about the possibility of a second marriage.

“… Louisa Dobede is a girl to be coveted, and, as mamma says, it might be happier for you if you married again. I thought you would be sure to do so.”

“No. She—who was my wife—lives.”

“What of that?” uttered Barbara, in simplicity.

He did not answer for a moment, and when he did, it was in a low, almost imperceptible tone, as he stood by the table at which Barbara sat, and looked down on her.

“‘Whosoever putteth away his wife, and marrieth another, committeth adultery.’”

And before Barbara could answer, if, indeed, she had found any answer to make, or had recovered her surprise, he had taken his hat and was gone.

East Lynne, Ch. XXVII

Lady Isabel is thoroughly punished. Her lover deserts her, her child is killed in a train accident in which she is maimed. She is rendered unrecognizable enough to return as governess to her abandoned children, one of whom dies in her arms. She herself dies. In a notorious narratorial intervention, the author assures her female readers that, ‘Whatever trials may be the lot of your married life’, they must ‘pray for strength to resist the demon that would tempt you to escape’. This escape, ‘if you do rush on to it, will be found worse than death’.

Oddly enough, in its tragic plot, that most amoral novels of adultery, Madame Bovary, seems to demonstrate the truth of this hyposthesis.

The protagonist marries in a state of overwhelming illusion. Marriage is a crushing disappointment. (No such excuse for Maria Rushworth.)

What is most memorable about Madame Bovary is the wife’s contempt for her husband. How brilliantly the novel captures this – the tedium of their sex life in the first months after marriage, the noises that he makes eating, the idiocy (to her mind) of his complete faith in her. What a fool!

Emma Bovary has been punished once for her folly and her romantic dreams, fed by too many novels, but being made into ‘Madame Bovary’. She is thoroughly punished at the terrible end of her story by suffering the most agonizing death from self-administered arsenic poisoning. The novel was hardly endorsing its protagonist’s betrayal of her marriage vows. Yet it outraged critics and readers in France – and eventually became notorious in Britain. Partly, I think, it is because the novel followed, even imitated, Emma’s increasing wilfulness. When she first has sex with Rodolphe, she is in the hands of a sophisticated practised seducer, who takes her out riding and then leaves the horses to walk her to a small clearing in the woods. He makes his move by telling her, ‘Vous êtes dans mon âme comme une madonne sur un piédestal’: ‘You are in my heart as a Madonna on a pedestal’.

‘Oh, Rodolphe!’ the young woman slowly sighed, and she leaned her head on his shoulder.

The stuff of her habit clung to the velvet of his coat. She tilted back her white neck, her throat swelled with a sigh, and, swooning, weeping, with a long shudder, hiding her face, she surrendered.

— Oh ! Rodolphe !… fit lentement la jeune femme en se penchant sur son épaule.

Le drap de sa robe s’accrochait au velours de l’habit. Elle renversa son cou blanc, qui se gonflait d’un soupir et, défaillante, tout en pleurs, avec un long frémissement et se cachant la figure, elle s’abandonna.

Gustave Flaubert, Madame Bovary, Part Two, 9

By the time that she is conducting her second affair, with the lawyer’s clerk Léon, her carelessness about secrecy or subterfuge is mimicked by the narrative, which (very rarely for a nineteenth-century novel) takes us into the lovers’ bedroom.

She snatched at her dress and tore at the thin laces of her corsets, which whistled down over her hips like a slithering adder. She tiptoed to the door on bare feet to make quite sure it was locked; then made a single movement and all her clothes fell to the floor. Pale, silent, serious, she sank into his arms with a long shudder.

Elle se déshabillait brutalement, arrachant le lacet mince de son corset, qui sifflait autour de ses hanches comme une couleuvre qui glisse. Elle allait sur la pointe de ses pieds nus regarder encore une fois si la porte était fermée, puis elle faisait d’un seul geste tomber enensemble tous ses vêtements;—et, pale, sans parler, sérieuse, elle s’abattait contre sa poitrine, avec un l,ong frisson.

Madame Bovary, Part Three, 6

There is nothing like this in the British novel of the nineteenth century!

Indeed, serious novels in English sometimes summoned up the dread possibility of adultery in order to deny it.

In Dombey and Son, Dickens had one of his rare changes of mind. The cold and utterly materialistic Mr Dombey treats his second wife, Edith, as if she is his possession. When he refuses to countenance an unofficial separation, she leaves him, eloping with his manager, Mr Carker. They flee together to France.

While still writing Dombey and Son, Dickens told John Forster that his friend Lord Jeffrey had protested against Edith Dombey’s impending adultery.

‘Note from Jeffrey this morning, who won't believe (positively refuses) that Edith is Carker's mistress.’

Dickens took note.

He was coming gaily towards her, when, in an instant, she caught the knife up from the table, and started one pace back.

“Stand still!” she said, “or I shall murder you!”

The sudden change in her, the towering fury and intense abhorrence sparkling in her eyes and lighting up her brow, made him stop as if a fire had stopped him.

“Stand still!” she said, “come no nearer me, upon your life!”

They both stood looking at each other. Rage and astonishment were in his face, but he controlled them, and said lightly,

“Come, come! Tush, we are alone, and out of everybody’s sight and hearing. Do you think to frighten me with these tricks of virtue?”

“Do you think to frighten me,” she answered fiercely, “from any purpose that I have, and any course I am resolved upon, by reminding me of the solitude of this place, and there being no help near? Me, who am here alone, designedly? If I feared you, should I not have avoided you? If I feared you, should I be here, in the dead of night, telling you to your face what I am going to tell?”

Dombey and Son, Ch. LIV

Some modern readers are as surprised as Mr Carker.

The novel of ‘adultery avoided’, as we might call it, is common enough in Victorian England.

Dickens does it again in David Copperfield, with the elderly Dr Strong and his young wife Annie, almost fatally tempted by the dashing young Jack Maldon. And in Hard Times, where Louisa Gradgrind, having been married off to the much older (and revolting) Bounderby, almost falls into the arms and bed of the louche young gentleman, James Harthouse.

You might even think of Middlemarch that way – Eliot considerately killing off Mr Casaubon so that Dorothea can be rewarded with Will Ladislaw.

Henry James has this kind of plot in mind in The Portrait of a Lady, where he introduces his heroine, Isobel Archer, to a world (and it is a corrupt world) where infidelity and adultery are normal for some sophisticated characters, and where Isobel is given every good reason to renounce her marriage vows. She has discovered that her husband, Gilbert Osmond, is deceitful and sadistic (and keeps company with a former mistress, by whom he has had an unacknowledged child). She leaves her husband in Italy and returns to o England, where Caspar Goodwood, whom she loves and who lovers her, asks her to leave with him.

“It would be an insult to you to assume that you care for the look of the thing, for what people will say, for the bottomless idiocy of the world. We’ve nothing to do with all that; we’re quite out of it; we look at things as they are. You took the great step in coming away; the next is nothing; it’s the natural one. I swear, as I stand here, that a woman deliberately made to suffer is justified in anything in life—in going down into the streets if that will help her! I know how you suffer, and that’s why I’m here. We can do absolutely as we please; to whom under the sun do we owe anything? What is it that holds us, what is it that has the smallest right to interfere in such a question as this? Such a question is between ourselves—and to say that is to settle it! Were we born to rot in our misery—were we born to be afraid? I never knew you afraid! If you’ll only trust me, how little you will be disappointed! The world’s all before us—and the world’s very big. I know something about that.”

Isabel gave a long murmur, like a creature in pain; it was as if he were pressing something that hurt her.

Henry James, The Portrait of a Lady (1881) Ch. LV

But she resists the temptation. When Caspar returns two days later for her answer, he finds that she is gone to Italy. Her husband, it would seem, is her destiny.

James also gave us one of the great novels of male adultery, The Golden Bowl.

Here we have a heroine who decides not to make too much of her husband’s infidelity, provided that she can put can stop to it. Is it the first ‘post-adultery’ novel?

Maggie Verver, a rich American heiress, marries Prince Amerigo, impoverished but alluring. Subsequently, Maggie’s father Adam, with her encouragement, marries her great friend Charlotte Stant. But, unknown to Maggie, Charlotte was once Amerigo’s mistress, and their relationship rekindles.

But then the supposedly naïve Maggie begins to work it out. And finally she confronts her husband.

Here is the crucial exchange between faithful wife (Maggie) and adulterous husband (Prince Amerigo). He has entered the room just after a distraught Mrs Assingham, accomplice in the adultery, has smashed that golden bowl, which was a wedding present to Maggie – but was flawed.

‘But what would you have done,’ he was by this time asking, ‘if I hadn’t come in?’

‘I don’t know.’ She had hesitated. ‘What would you?’

‘Oh; I oh—that isn’t the question. I depend upon you. I go on. You would have spoken to-morrow?’

‘I think I would have waited.’

‘And for what?’ he asked.

‘To see what difference it would make for myself. My possession at last, I mean, of real knowledge.’

‘Oh!’ said the Prince.

‘My only point now, at any rate,’ she went on, ‘is the difference, as I say, that it may make for you. Your knowing was—from the moment you did come in—all I had in view.’ And she sounded it again—he should have it once more. ‘Your knowing that I’ve ceased—’

‘That you’ve ceased—?’ With her pause, in fact, she had fairly made him press her for it.

‘Why, to be as I was. Not to know.’

Henry James, The Golden Bowl (1904) XXXIV

Not only is the word ‘adultery’ not mentioned – almost nothing is mentioned. ‘Know’ is an intransitive verb. Everything is implicit.

By her indirection, Maggie wins her husband back (and sends her father and Charlotte safely back to America).

The possibility of divorce does not change everything.

One of the great twentieth-century divorce novels, Evelyn Waugh’s A Handful of Dust, is written, there is no doubt, out of the author’s deep bitterness at the discovery of his own wife’s affair.

The novel that came out of it inverted all the traditional novelistic values. It imagined a world where adultery was not only accepted, it was advocated. Waugh’s protagonist, the good-hearted, country-dwelling Tony Last, is almost the only person who does not know what his wife, Brenda, is up to on her incessant trips up to London.

…opinion was greatly in favour of Brenda's adventure. The morning telephone buzzed with news of her; even people with whom she had the barest acquaintance were delighted to relate that they had seen her and Beaver the evening before at a restaurant or cinema. It had been an autumn of very sparse and meagre romance; only the most obvious people had parted or come together, and Brenda was filling a want long felt by those whose simple, vicarious pleasure it was to discuss the subject in bed over the telephone. For them her circumstances shed peculiar glamour; for five years she had been a legendary, almost ghostly name, the imprisoned princess of fairy story, and now that she had emerged there was more enchantment in the occurrence than in the mere change of habit of any other circumspect wife.

Evelyn Waugh, A Handful of Dust (1934), Ch. II

Recent novelists almost never use the word adultery, but often enough they still need the idea – the memory of that original sin.

Zadie Smith’s On Beauty (2005) is, in large part, a novel about marriage. And if you want to write a novel about marriage, how better than to depict adultery and its consequences? Howard Belsey is a not particularly successful Art History academic (an expert on Rembrandt, as it happens) at a small New England university. He is in his mid-50s and has long been married to Kiki. Howard is British, and white; Kiki is African-American. They have three children, in their late teens or early twenties.

Early in the novel, we find out that Howard has been unfaithful, and that his wife knows about this. She believes that it has been a one-night stand with a woman whom her husband did not know. She is deciding how forgivable this infidelity might be, but from Howard’s point of view, things don’t look too bad. ‘His infidelity had not ended everything, after all. It had been self-pity to think that, and self-aggrandizement. Life went on.’ (Ch. 12).

But then, at a party that she and Howard are giving, Kiki sees something that changes the meaning of what Howard has done. One of the guests is Claire Malcolm, a colleague of Howard’s and a friend of Kiki’s. At the party, Claire and Howard are playfully arguing about the importance or irrelevance of Rembrandt and Wallace Stevens.

Claire versus Howard. Howard felt one of her fingers thoughtlessly, drunkenly, slip under a gap in his shirt to his skin. Just then they were interrupted.

‘What are you two gossiping about?’

Too quickly, Claire removed her hand from Howard’s body. But Kiki wasn’t looking at Claire; she was looking at Howard. You’re married to someone for thirty years: you know their face like you know your own name. It was so quick and yet so absolute – the deception was over.

Zadie Smith, On Beauty (2005), Ch. 12

The deception is the lie that he has merely been unfaithful. In fact, he has been having a long affair (though he thinks that it is now over). He has been guilty, we might say, of adultery. This is not so forgivable.

One of the most interesting recent British novels that turns on adultery is Tessa Hadley’s Free Love (2022). This seems to set out to test the notion that a ‘sexual revolution’ beginning in the 1960s might have forever changed the meaning of adultery – might even have made it an antique word and idea.

We find that the title is thoroughly sardonic, perhaps sarcastic. Phyllis Fischer, a civil servant’s wife aged 40, has two children and lives in the suburbs. One day, she and her husband, Roger, had a friend’s son, Nicky, in his early 20s, to supper. Late in the evening, in the back garden, Phyllis kisses him. Soon she is travelling in to London, to a memorably seedy 1960s Notting hill, to consummate her ‘unhinged’ (it is her word) passion. The affair begins, and she starts making calculations that are brilliantly observed – and that it perhaps takes a female novelist to realize.

Her husband has proposed sending her young son to a boarding school, Abingdon. She has resisted, but one day, at Sunday lunch in Guildford with Roger’s sister, she wonders about conceding.

Some vision of compensation flashed in her thoughts, as brilliantly illogical as those floating objects made of light that swam in front of her eyes before a migraine; though she hadn’t meant to think about Nicky Knight while she was in Guildford, couldn’t think about him. He couldn’t exist, not here, in this company today – not with his long hair, scruffy flared trousers, unbuttoned unironed shirt, drawling mockery, thin smiles, offensive opinions, deliciously offensive everything. It wasn’t exactly, though, that she thought of him. It was more like sensation, a finger drawn down her body, melting and undoing her, assuaging the impending loss of her little son, which hurt so absurdly much. To block out the hurt she imagined herself bargaining, accepting Abingdon in exchange for that room in Ladbroke Grove, as if the two places existed in some significant and consoling relation, although she knew they didn’t.

A woman’s understanding of adultery?

Later, in a letter to an old (female) friend, telling her the Phyllis has left him, Roger says, ‘From my perspective, it’s been rather more like something out of a comic opera than Anna Karenina’. This is, after all, the modern world. But maybe it is still like Anna Karenina – the old adultery plot is irresistible.

© Professor Mullan 2022

Part of:

This event was on Wed, 26 Oct 2022

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login