Powell and Pressburger: The Matter of Britain

Share

- Details

- Text

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

World War Two set British filmmakers a challenge: to be relevant and entertaining and to inspire without patronising. Powell and Pressburger brought wit and imagination to their task, questioning what Britain stood for, warts and all. Notoriously, Churchill hated The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp. But many ordinary cinema-goers were grateful for The Archers’ poetic patriotism, in this as well as in A Matter of Life and Death. Britishness redefined in the stress of war is the theme of this lecture.

Download Text

11th November 2019

Powell and Pressburger: The Matter of Britain

Professor Ian Christie

It’s easy to forget today that The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp was for long Britain’s unknown war film. Although it was the longest, and probably the most controversial film made during World War Two – and one of the few made in Technicolor – it effectively disappeared during the late 1940s, until it was resurrected in 1985. For those who already know the film, this 40-year absence has a special irony, since its remarkable flashback structure turns on its hero recalling ‘forty years ago’, as we plunge back into the river of time (actually a swimming pool) to discover his younger self. Now we will soon have had access to the film for forty years since its recovery. And what are we to make of it? As one leading contemporary critic pondered in 1943: ‘What is it really about?’

I’ve called this lecture ‘The Matter of Britain’, which might suggest that I’m going to connect P&P’s film with Arthurian legend, traditionally known by this general title. But I’m not going to make that connection immediately. Instead I want to move past the contextual matters of how the film was nearly banned, why Churchill hated it, and why it’s now widely regarded as the Archers’ masterpiece. These have perhaps occupied too much attention since the film’s reappearance, obscuring the question of what it’s ‘really about’ in the context of 1943. So what does it consist of? The story traces a friendship between a German and an Englishman across forty years – yes that interval again – and the exchange that links them, when the German wins the love of the woman whom the Englishman has set out to rescue in the film’s earliest episode.

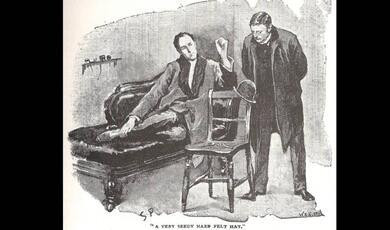

The figure of Blimp, seen in a tapestry in the credits, is perhaps more than a nod to the cartoon origins of the character. It could be related to the mock-chivalric figure of Don Quixote, or to the fictitious Russian soldier Lieutenant Kije, now best known from Prokofiev’s music for the 1934 Soviet film. Blimp had been a cartoon figure created by David Low to satirise British complacency during the 1930s, with expostulations that usually began, ‘Gad Sir…’. For Low, giving his blessing to Powell and Pressburger’s plan, he was definitely ‘a fool’, and had to be shown to be so at the end, whatever else they created as ‘backstory’ for him.

Curiously, the evolution of Pressburger’s script was partly under the title ‘The Life and Death of “Sugar Candy”’. Was this a ‘cover’ for their real intention, knowing that references to Col Blimp would be incendiary for the powers that be? If so, it was an interesting choice of name – since Low considered their work ‘an extremely sentimental film about a glamorous old colonel’. However, there is also an aside in a draft letter from Powell to Sir James Grigg in 1942, protesting about the latter’s rejection of the film, saying that they ‘will change the title’.

At any rate, the film was in full development during May1942, as we know from several letters that have survived (printed in my edition of the script). The most valuable is one from Powell to Wendy Hiller, then being wooed to play the eternal object of Clive’s affection. Here Powell tells how Pressburger had the idea while they were working on One of Our Aircraft is Missing, to show how ‘Blimps are made not born’, adding: ‘let is show that their aversion to any form of change springs from the very qualities that have made them invaluable in action’. He writes that their Blimp ‘has fought in three wars with honour and distinction and has not the slightest idea what any of them were really about’. For Powell, he was ‘a comic, a pathetic, and a controversial figure’. Interestingly, another surviving letter is Laurence Olivier’s detailed reaction to the script, in which he disagrees quite strongly with the development of its ‘masterly idea’, complaining that Powell and Pressburger ‘don’t say what makes him a Blimp’. For Olivier, this would have been due to a litany of essentially Tory attitudes to tradition, which lull Clive into ‘feeling that everything’s all right’, allied to the national malaise of ‘we’ll muddle through’. Olivier invokes the Elizabethans (Drake), and also Nelson – no doubt inspired by having recently played him in Korda’s That Hamilton Woman.

In the event, Hiller was unable to play the triple part, having become pregnant shortly before production began, while Olivier was not released from service due to mounting War Office and Cabinet hostility to the project. Astonishingly, The Archers managed to make this vast epic of British life across nearly half a century in the teeth of official opposition, and with the full backing of the conservative Arthur Rank, who had become the central figure in British cinema. It opened at his cinemas in mid-1943 with much fanfare: comparisons were made with Gone With the Wind, and the trade press claimed it as ‘the film by which all entertainment, past, present and future, will be judged’. We know that it was promoted with references to the official opposition (‘see the film they tried to ban’; and Low’s cartoon of massed civil servants viewing it). And, unusually, we also that it made a favourable impression on ordinary filmgoers (thanks to Mass Observation ‘s 1943 inquiry about ‘favourite films’, in which it came first in women’s lists and narrowly second in men’s, with many appreciative comments). But it puzzled many critics – like C. A. Lejeune – and angered much of the right-wing press, like the Daily Mail: ‘a gross travesty of the intelligence and behaviour of British army officers as a class’. Other papers and pamphleteers questioned its portrayal of a ‘good German’, attributing this maliciously to Pressburger’s background.

Churchill’s hostility succeeded in preventing the film being seen in the US until 1945, by which time it had lost much of the topicality it had in 1943. By now its length was also against it, and it was cut and reshaped, before becoming a truncated shadow of its original epic form – only to re-emerge, in its original splendour, as an early part of the modern wave of film restorations, following Kevin Brownlow’s reconstruction of Gance’s Napoleon, first shown in 1980.

Viewed from the perspective of the mid-80s, and subsequently, the romantic and daring cinematic aspects of the film inevitably loom largest, leading to comparisons with Citizen Kane (see Haskell’s Criterion essay from an American standpoint). But can we replace it in its 1940s context, to ask how it fits into The Archer’s evolving study of ‘the matter of Britain’? Let me offer two rarely considered pieces of contemporary evidence, which certainly influenced Powell and Pressburger’s path towards the wartime patriotism of Blimp. One is a verse-novel by the American poet Alice Duer Miller, The White Cliffs, published in 1940. This story of an American woman who has adopted England and lost her husband in WW1 so impressed Pressburger that he seriously considered it as the basis for a film in 1941; and his grandson, Kevin Macdonald has suggested it would influence the time-frame of Blimp. Its final lines were apparently proposed by Pressburger to his friend George Mikes to serve as the epigraph of Mikes’ 1946 classic, How to Be an Alien:

I am American bred

I have seen much to hate here – much to forgive,

But in a world in which England is finished and dead,

I do not wish to live.

My other contemporary evidence is a short film made by Powell, apparently on a personal impulse, in 1941. This is a dramatization of a letter from a pilot to his mother that had been made public after his death, which conveys an almost mystical patriotism which would influence both Blimp and A Matter of Life and Death (show: An Airman’s Letter to his Mother).

With hindsight, we can trace a line from 49th Parallel, set in the Canada that was still an outpost of the British Empire, through One of Our Aircraft to Blimp, and on to A Canterbury Tale and A Matter of Life and Death. These all express doubts about how Britain can meet the challenge of Nazi Germany. In 49th Parallel it is, in modern terms, the multi-culturalism of Canada against Lt Hirth’s Nazi doctrine of German supremacy. Will that diversity be strong enough to defeat the Nazi claim of manifest destiny? In One of Our Aircraft, the crew of a British bomber who have bailed out over the Netherlands meet Dutch people living under German occupation: many prepared to risk their lives as resisters, but others acting as quislings – a theme also explored in Cavalcanti’s Went the Day Well? in the same year; and later in Brownlow’s It Happened Here. The centrepiece of Blimp in this sequence must be Theo’s indictment of Britain’s reluctance to recognise the Nazi menace during his testimony to the president of the tribunal - devastating because of its impassioned modesty in Walbrook’s performance.

After Blimp, The Archers clearly felt they had more to explore in England’s history; and in A Canterbury Tale they set out to penetrate the ‘deep England’ of Kent and Canterbury. In this modern pilgrimage, three outsiders discover connections with rural England, and with its initially forbidding guardian, Culpepper, who is like a genius loci. But as well as an antiquarian, keen to impart historical information about Kent, he is also a progressive figure, even a pioneer ecologist, as I discovered from the books seen on his desk (such as Soil and Sense). Then in A Matter of Life and Death, conceived during but made immediately after the war, there is an expansive vision of Britain, poised on the threshold of a new world, where its history and identity need to be re-examined and re-asserted. The pilot Peter Carter may be a carefully balanced embodiment of 1945 – ‘Conservative by nature, Labour by experience’ – as the film began shooting just weeks after the General Election that brought Labour to power in July. But in the heavenly trial to decide if he will live or die on earth, his counsel has to defend Britain’s historical record of imperialism. Britain and America may be pledged to marriage in the film’s romance, but not without misgivings. Before inviting the jury to give their verdict, the judge quotes Walter Scott’s Love:

In peace, Love tunes the shepherd’s reed;

In war, he mounts the warrior’s steed;

In halls, in gay attire is seen;

In hamlets, dances on the green.

Love rules the court, the camp, the grove,

And men below and saints above;

For love is heaven, and heaven is love.

Will love be sufficient to overcome the strains that lie ahead in the postwar world? We know that while the film was being made, British diplomats were reporting negative attitudes to Britain’s legacy of empire (see my book on the film).

And where does Blimp stand in the evolving debate about Britain’s destiny? Perhaps the most striking feature of its structure is the tissue of absences that make up Clive Candy’s life history. Like a caricature Quixote, he gallops into battle to defend the honour of a lady he hardly knows in the Edwardian era, immediately after the Boer War. Having lost her to his German rival, he finds her substitute in a nurse glimpsed on the Western Front in WW1. The record of their marriage is a tour of the outposts of the Empire, for which Powell claimed he borrowed the album of his military adviser, Lt.General Brownrigg, who had a remarkably similar career to that of Clive Candy. His final humiliation is to be dropped by the BBC, in favour of an inspiring talk by J. B. Priestley.

So Blimp is both a mock-epic, poking fun at the Victorian attitudes of its anti-hero, and something of a lament for the loss of his – Britain’s? – innocence in the era of total war. Here, we might also consider one of the film’s mythic references, in a daring mise-en-abyme. Clive visits the theatre to see a play, actually Stephen Phillips’ verse drama Ulysses, which enjoyed great success in London in 1902. The play’s theme was identified in a review as ‘a wanderer's return. The yearning of the seafarer for his home and all that home means, for the sight of wife and child and friends, and of the kind land that gave him birth’. Clive Candy is both a warrior and a wanderer, in search of home, so the visit to Phillips neo-classical play, in which Beerbohn Tree played Ulysses, is as poignant as the Berlin duel scene, accurately based on a turn-of-the century German duelling manual, found in the British Museum by Pressburger while researching his script.

I have tried to demonstrate that there is no simple answer to Lejeune’s question about what Blimp means. The skirmishes with Churchill – who may have seen an image of himself in Low’s cartoon figure – and with right-wing press and critics keen to label the film ‘pro-German’ both belong to the 1940s. Like Citizen Kane, once read in proximity to its real-life inspiration, William Randolph Hearst, Blimp has floated free, offering a wryly ironic view of England’s, or Britain’s, strengths and weaknesses. Distanced from the raw patriotism of The White Cliffs or An Airman’s Letter, it also drew on the remarkable fusion of Pressburger’s and Powell’s quite separate cultures in the furnace of wartime Britain. And as such it makes a unique contribution to the continuing ‘matter of Britain’.

© Professor Ian Christie 2019

Bibliography

Ian Christie, Arrows of Desire: The Films of Powell and Pressburger, Faber 1994

--------------- ed., The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, Faber 1994

--------------- A Matter of Life and Death, BFI Classics 2000

--------------- ‘History is now and England’ on A Canterbury Tale, in Christie and Moor, eds, Michael Powell: International Perspectives on an English Film-maker, British Film Institute 2005

David Low, An Autobiography, Simon and Shuster, 1957

Kavin Macdonald, Emeric Pressburger: the Life and Death of a Screenwriter, Faber, 1994

Jeffrey Richards and Dorothy Kennings, eds, Mass Observation at the Movies, Routledge, 1987

Bibliography

Ian Christie, Arrows of Desire: The Films of Powell and Pressburger, Faber 1994

ed., The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, Faber 1994

A Matter of Life and Death, BFI Classics 2000

‘History is now and England’ on A Canterbury Tale, in Christie and Moor, eds, Michael Powell: International Perspectives on an English Film-maker, British Film Institute 2005

David Low, An Autobiography, Simon and Shuster, 1957

Kavin Macdonald, Emeric Pressburger: the Life and Death of a Screenwriter, Faber, 1994

Jeffrey Richards and Dorothy Kennings, eds, Mass Observation at the Movies, Routledge, 1987

Part of:

This event was on Mon, 11 Nov 2019

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham College plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login