The General Election, February 1974

Share

- Details

- Text

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

This was the 'who governs' election, fought in the midst of a miners strike. Edward Heath appealed for a mandate to adopt a strong policy towards the trade unions, but was denied it. The outcome was the first hung parliament since 1929, and a Labour minority government which went to the country after just seven months. The Liberals gained their best result – 19% of the vote – since the 1920s, but only 14 seats in the Commons. The Scottish nationalists also made striking advances. The February 1974 election inaugurated the era of multi-party politics in Britain.

Download Text

20 January 2015

The General Election:

February 1974

Professor Vernon Bogdanor

This lecture is on the February 1974 Election. It is the third in a series of six on significant post-War elections, and I think this is the most significant and important election of all. It was a crisis election, the only crisis election in Britain since the War, held amidst a miners’ strike, in really unique circumstances because the Government was really pushed, or felt itself pushed, to go to the country to call an election when it did not really want to do so and it still had a working majority in Parliament, which, as you can see, it lost. The Government still had another sixteen months of its term left, and the Election was called then at the behest not of the Government but of the coal miners, who had called a national strike against the Government’s statutory incomes policy. The conditions were really stark. There was a miners’ strike, a three-day week, and a state of emergency, and some would say the country was also held amidst a constitutional crisis, a crisis of legitimacy. It sometimes called the “Who Governs?” election. But if you look at the outcome, the answer the British voter gave to the question “Who Governs?” was “None of you,” because it led to a hung parliament, and the election gave the first indication that the two-party system might be crumbling. You will see the Liberals gained 19% of the vote, though very few seats – they gained nearly a fifth of the vote.

And this was the only post-War hung parliament before that of 2010, but it is very different from the hung parliament of 2010 because, in 2010, after a few days’ negotiation, there was a coalition government between the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats which has a comfortable majority of 78 in the House of Commons, and whether you favour this Government or not, I think you would have to agree it is provided strong and stable government, it has not been in danger of defeat in the Commons, and contrary to the expectations of many, including I have to say myself, it is lasting for the full term of five years. But you can see, the situation there was quite different because not only could no single party command a majority but no two parties together, except for Conservatives and Labour, could command a majority. You need 318 seats for a majority, and no parties could do it, so if you wanted a coalition, it would have to be a three party coalition.

Now, in the event, Edward Heath, the Prime Minister, tried to secure a coalition with the Liberals, but that did not work and the Conservatives were resigned and they were replaced by a Labour Government, a minority government, led by Harold Wilson, and that Government survived for seven months and then there was a second General Election that year, the first time that had happened since 1910. Labour then, in that second election, got a very narrow overall majority of three seats.

But this election also showed, as well as the rise of the Liberals, you can see the rise of the Scottish Nationalists, and it showed that nationalism was a growing force in Scotland in particular. In Northern Ireland, the Unionist Parties in Northern Ireland, who had previously supported the Conservatives, no longer did so and were independent, as they are now. And I think all this may be of more than historical interest because some people predict this is what is going to happen this year, that we are going to have a hung parliament, not like 2010, but a fragmented one, in which the Liberal Democrats, with many fewer seats, will not be able to get any other party over the line for an overall majority, and possible gains again for the Scottish Nationalists.

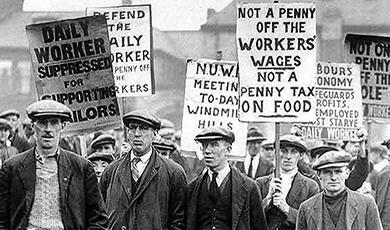

Now, as I have said, this Election was called the “Who Governs?” Election, but it raised a further question, a more difficult one to answer really: was Britain governable? In particular, was Britain governable against the wishes of powerful trade unions?

The Labour Government, which succeeded Edward Heath, despite its close links with the unions, also ran into trouble with them, and it was finally destroyed in 1978/9 by a wave of public sector strikes, called the Winter of Discontent.

Some argued in 1974 that the experience of the Heath Government showed that one could not govern without the consent of the trade unions, but the experience of the Labour Government which followed seemed to show you could not govern with their consent either, and the issue was not finally settled until Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative Government removed the trade union veto in 1985, when she defeated another miners’ strike led by Arthur Scargill, which was much longer lasting than the one in 1973/4. It lasted 11 months and marked by much greater violence. But during the 1970s, that question “Who governs?” was to remain unresolved.

The Heath Government had come to power in 1970, rather unexpectedly. 1970, incidentally, is the only occasion since the War when a party with the working majority has been replaced by the opposition party with a working majority. It is the only occasion when it has happened. And it was unexpected, an unexpected victory for Heath, because, a week before the Election, one poll had shown a 12% lead for the Labour Party. The Economist published a cover on the week of the Election showing Harold Wilson, and Roy Jenkins, his Chancellor, under the caption “Life in Wilson’s Britain”, assuming that Labour would win. The Conservative Party were making plans to seek Heath’s resignation immediately after the Election – Lord Carrington was going to visit him with, as it were, a loaded pistol. But that did not happen, and Heath’s unexpected victory gave him considerable authority over his Cabinet and his party. The Economist said, after the Election, “Only one man has really won this Election and that man is Edward Heath.” But it may also have given him excessive confidence in his own judgement.

Certainly, the Conservative programme bore all the imprints of Heath’s leadership. His strategy, since he had become Conservative leader in 1965, had been clear. He wanted to reform the economy by introducing more competition and removing the dead hand of the State. He wanted to end restrictive practices and bring the trade unions within the framework of the law. At the same time, he promised to end the Labour Party’s incomes policy and restore free collective bargaining between unions and employers. Above all, he was determined to get Britain into the European Community, as the European Union was then known, and that was I think his main ambition. His first speech as a backbench MP in 1950 had been to propose that Britain join the European Coal & Steel Community, the precursor of the European Community and the European Union.

Now, the Heath Government was extraordinarily united. There was not one single resignation on policy during the period of the government and great loyalty to the Prime Minister. Indeed, it was so united, there seems never to have been a vote in the Cabinet. Decisions were reached by agreement and consensus after discussion. Now, a complaint against Heath was not that his Government was divided, but that it was not divided enough, that it was a Cabinet of likeminded people, all of whom agreed with Heath, but dissenters and questioners had been excluded. The Cabinet agreed on the strategy laid out by Heath, which I have just described, the strategy of 1970, but then, in 1972, it also agreed on a quite opposite strategy, the famous U-turn, a policy of intervention in industry and a statutory incomes policy, and these were policies the Conservatives had expressly repudiated in 1970. Indeed, when they were adopted, Harold Wilson, who was now Leader of the Opposition, he congratulated Heath on his conversion to socialism.

This U-turn caused great problems for the Government and some resentment amongst backbenchers, who felt he was introducing, if not socialism, then some form of corporatism. It was unattractive for most Conservatives to see the State to be intervening to such an extent in industrial matters and in wages because Conservatives, after all, believe in minimising, not in extending, the role of the State. This new disposition therefore was ideologically unattractive to Conservatives and could be justified only by success.

There was a further problem: that Heath was not a very skilful communicator and found it difficult to put his policies across, either to the party or the country, and that may be one of the reasons why he did not win the February 1974 Election. If democracy is, in essence, government by explanation, this was a crippling weakness.

Until 1974, however, it did not seem to matter too much because it seemed that Heath could simply bulldoze his way to victory, as he had done in 1970. His mastery of facts and figures, his sheer depth of knowledge, and his commitment on issues such as Europe, seemed sufficient to overcome all opposition. But it meant that, when crisis came, voters did not warm to him, nor sympathise with the message he was trying to convey.

So, why did the Conservatives change course in 1972? In 1970, they proposed a policy of free collective bargaining, but that could only work, so it seemed, in the private sector. What about the nationalised industries? The ‘70s of course were the days before privatisation and there was a large nationalised sector in which wages were determined as much by government decisions as by the market because nationalised industries were not subject to the same market disciplines as the private sector. They could never say, as a private firm could, “If we meet this wage claim, we will be forced to go out of business.” More money could always be made available from the Government. So the determination of wages in the nationalised sector was bound to be, in part, a political decision.

Heath proposed a policy of gradually reducing wages in the public sector, but the policy collapsed with the first miners’ strike in 1972, when the extent of picketing and sympathy from other trade unions forced Heath to concede defeat, and the miners were given a very substantial wage increase of well over 20%. Now, Heath introduced the statutory incomes policy in 1972 in response to this defeat, and on the day on which the miners’ settlement was announced, Heath said: “We have to find a more sensible way of settling our differences.” He initiated talks with the trade unions on voluntary wage restraint, but when these talks failed, he introduced a statutory policy.

Now, one of the reasons why talks with the trade unions failed was due to trade union hostility to the Industrial Relations Act of 1971, and this sought to bring the trade unions within the framework of the law, but because of their bad experience with the courts in the early twentieth century, the trade unions were very suspicious of the law, even when it seemed to be giving them benefits, and they wanted to retain free collective bargaining. From the first, everything went wrong with the Industrial Relations Act. Against the expectations of the Government, most trade unions refused to register under it, and the TUC expelled those few unions that did register, and the Act seemed to do little to alleviate industrial problems. Indeed, by antagonising the unions, it made them worse, and it also annoyed many employers since it seemed to be making labour relations more difficult.

The trade unions had already forced the previous Labour Government to withdraw similar proposals, called “In Place of Strife”, and the Conservatives never asked themselves the question “If the Labour Party, with its strong links with the unions, could not secure the consent of the unions to industrial relations legislation, how on earth would the Conservatives be able to do it?” And so, relations with the unions were strained already when the incomes policy was introduced.

Now, this policy gradually became more and more complex, and by Autumn 1973, a stage three of the policy was announced, which set a limit of 7%, a statutory limit of 7% on incomes, and a statutory limit for any individual of £2.25 per week and a total of £350 per year. The key question was whether the miners would accept this policy. Difficult for us to understand now because there are hardly any mines left in Britain, but at that time, the miners were the seventh largest union, with over a quarter of a million members, and even more important, there was much sympathy for them in other parts of the trade union movement because it was felt they were doing an unpleasant and unattractive job. I think there was also a much wider sympathy in society as well for the miners, including perhaps in some unexpected places. During the second miners’ strike, the Queen Mother is supposed to have said, “I wonder how Mr Heath would like to go down the mines?” I think that was [a] general feeling.

Ministers were well aware that there would be a problem with the miners, so in July 1973, three months before the policy was announced, Heath had a secret meeting with the President of the National Union of Mineworkers, a man called Joe Gormley. Gormley was a moderate and perfectly prepared to agree to the Government, and they agreed that there should be an escape clause for the miners because there had be an extra criterion in the statutory policy in which any group of workers could get more money if they worked, and I quote, “unsocial hours”. Heath said this would be used to give the miners more than the 7%, and Gormley said that is fine and that was a deal, and the Government breathed a sigh of relief that the problem was over. They made a number of false assumptions… They first assumed that Gormley was fully in control of his union and could control the militants. They then assumed that, even if there would be industrial action, it would not be as dangerous as in 1972 because coal stocks were higher and they thought would get them through the winter.

And it was with some confidence that Heath spoke at the Conservative Party Conference in the Autumn of 1973, in October, and that was to be his last speech to a Conservative Conference as Prime Minister, though of course he did not know that at the time. He said: “Too often in the past, a strike was the only way for a union to make its views known. Those days are past. Our talks in Downing Street are held regularly, before there is a dispute. They have had more influence on policy than any number of demonstrations or strikes.” But he spoke too soon…

When the negotiations with the miners began, the Coal Board immediately offered the full amount allowed under stage three, which, with the escape clauses, probably amounted to around 10%. Now, the Board was criticised for offering the maximum immediately and offering no scope for negotiation, but the trouble was that under the statutory incomes policy, the maximum immediately became the minimum, so it was very difficult to negotiate at all. Anyway, the miners rejected the deal. They said the unsocial hours’ criterion would give some miners more than others, and they wanted more for all, and that would mean breaking stage three.

Ministers, not unnaturally, felt they had reached an agreement and that the Miners’ Union was betraying them, but the truth is that they, and Heath in particular, misunderstood the trade union movement. They assumed that Gormley and the other moderate leaders could command their members. That may have been true in the past. By the 1970s, it was no longer true. Deference to leaders was coming to an end in all walks of life. In the trade unions, it meant power to the shop floor, and the statutory incomes policy increased the power of militants because they could always say the moderate leadership had sold out and that the miners could get more money by going on strike, as they had in 1972.

In his memoirs, Gormley reflects: “The incomes policy had put us in a false position. Our role in society is to look after our members, not run the country. It was not the role of the unions to police incomes policies on behalf of governments.”

But Heath had been an army officer in the War and then a whip in the Churchill, Eden and Macmillan Governments. He lived in a world where authority was not to be questioned. He lived in a command and control world. He saw himself as Prime Minister as the commanding officer of the nation. The Cabinet would make its decisions after discussions, including discussions with the trade unions, and these decisions would then be carried out. One hands down orders and things happen. You tell businessmen to invest in the needs of the economy, and they invest. You tell the unions to hold down wages, and they comply. Now, that was the world of disciplined authority. It was the world of the War and the immediate post-War years. It was not the world of the 1970s.

Then a further crucial factor came into play, which completely undermined the policy. Just two days before stage three was announced, a war broke out in the Middle East, and the Arab States, on which Britain then depended for two-thirds of her oil, decided to retaliate against the West for what they saw as Western support for Israel, and they said they would cut oil production by 25% and they threatened to quadruple oil prices – in fact, oil prices doubled. All this came on top of increases that had already occurred in world commodity prices, in particular raw materials and foodstuffs, so everyone’s standard of living was falling very rapidly. Inflation was growing and more wages were needed to keep up. And all this set a wholly new context for British politics.

It meant, first, that plans to expand the economy and the improvements in living standards which Heath had hoped would reconcile the unions to wage restraint, all those plans would have to come to an end. The dash for growth was over. Some economists say the policy was, in any case, unsustainable, but whether so or not, it would have to come to an end. In retrospect, we can now see that 1973 was the watershed in which the long boom of the immediate post-War years, the boom which would sustain the post-War consensus, that was coming to an end.

But the second, and more immediate, effect of the rise in the price of oil was that coal became much more important to the British economy. Many people asked “Why should we pay more for oil when we have got our own coal? Instead of paying more to the Sheiks in the Middle East to send oil to Britain, why not pay British miners to produce more coal, which would still be cheaper than oil?” One union leader asked Heath, “If a Government is prepared to pay the Sheiks for oil, why not pay the miners for coal?” The whole strategy of replacing coal by oil was undermined and the bargaining position of the miners immeasurably strengthened. Stage three was beginning to appear highly unpatriotic.

Now, miners, having rejected the offer by the Coal Board, voted for an overtime ban and cut production by 30%. The electricians then proclaimed their own overtime ban in sympathy with the miners. The Government responded by declaring a state of emergency, the fifth in just over three years of the Heath Government. There had only been seven others since 1920, since the idea of a state of emergency received statutory recognition. Street lighting was curtailed, floodlighting banned, a 50 mph speed limit on roads to limit consumption of petrol – some argued for petrol rationing, though the Government did not accept that, and worst of all for most people, all television programmes by 10.30pm. Some thought that was just a gimmick for the Government to enhance the crisis atmosphere. At this stage, some people began to argue for an early election.

Now, what was the Government to do? It seemed trapped. On market principles, it ought no doubt to have responded to the Middle East war by increasing the offer to the miners. But four million workers had already settled under stage three, and counted themselves lucky to do so, given the problems the economy faced. Perhaps they would also seek more money if the miners got more money. Most important for Heath, Conservatives on the backbenches and the country simply would not countenance what they would see as a second surrender to the miners, the first having been in 1972. Douglas Herd, who was Heath’s Political Secretary at the time told him: “A settlement in manifest breach of stage three would not be possible for this Government because it could destroy its authority and break the morale of the Conservative Party.” One backbencher put it more pithily: “If Heath gives in, he’s had it!” On December 12th, there was a headline in the newspapers, “Ministers predict an Election if the industrial situation gets worse”.

This is, of course, before the days of the Fixed Term Parliament Act, which came into law in 2011, and the decision on the election was not a Cabinet decision but one for the Prime Minister. On every other matter, the Cabinet collectively decides. At that time, the decision to have an election, the Cabinet and no doubt other people advise, it is a very lonely decision for the Prime Minister to make. Perhaps you all ought to put yourselves in the position of Edward Heath and consider whether you would have called an election…

After the Election was lost, one of Heath’s advisors said, “Look, you must not blame yourself, you know,” and Heath said, “I am to blame - for taking your advice.”

Now, all Heath’s instincts were against an early election, and that was not because he feared he might lose but almost the opposite reason, he feared he might win and he thought that would polarise the country. He did not want to polarise the country in a “Government versus miners” election. He had grown up in the years of a post-War settlement, when Government and the unions worked together. The unions were given a voice in policymaking, in Conservative as well as Labour Governments, and in return, they would act with moderation. The Government, for its part, would ensure that it did not return to the unemployment of the inter-War years and it did not return to the confrontation of the General Strike. Heath, in particular, had great contempt for the Conservative Governments between the Wars, which he said had tolerated a very high level of unemployment. He thought everyone should work together for the prosperity of the country. But perhaps, politically, if people thought there might be an early election, this might help settle the strike because the Labour Party might fear it would lose such an election and put pressure on the miners to settle, so it might not do harm if the idea that there was an early election got about.

Heath then called the miners to Number 10 and said that he had found a further way out of the problem. He said the Pay Board, which had been set up to police the statutory incomes policy, was shortly going to produce a report on wage relativities, and he was fairly sure that would recommend more to be paid to the miners. He said he would also review investment and increased pensions and health benefits for the miners, and he asked the miners if they would accept this new offer. Gormley was, again, in favour, but his Executive voted 18 to 5 against putting it to a ballot, Gormley being one of the 5. It was not that the militants, as the Conservatives thought, had a majority in the union Executive. The moderates had a very narrow majority, but they said, understandably, if you keep up pressure against the Government, they are on the run and you will get more concessions. But the Vice-President of the National Union of Miners, a man called Mick McGahey, was a member of the Communist Party, and he is alleged to have told Heath at the meeting at Number 10 that he was determined to break the pay policy to get him out of office. It is not clear whether he said it or not. It was put about that he had said it, and was to be much-quoted by the Conservatives during the Election campaign.

After the miners refused to put this offer to a ballot, the situation rapidly worsened. On the railways, the union called a ban on overtime and a work-to-rule following an inter-union dispute. Sunday trains stopped and there was disruption in suburban services. The day after this was announced, the Government proposed a three-day week to save electricity, in an attempt to cut electricity consumption, and then hopefully the country could get through the winter. The new Energy Minister, Patrick Jenkin, distinguished himself by saying that all could help in saving electricity if they would brush their teeth in the dark… The Government also introduced an emergency budget announcing cuts in public spending.

Now, you may think that is bad enough, but there were even further problems the Government faced, serious ones, in Northern Ireland at the time with terrorism, because, after very difficult negotiations, they had reached an agreement with the various parties in the province which was called the Sunningdale Agreement, which provided for a power-sharing executive in Northern Ireland, rather similar to that negotiated 25 years later by Tony Blair. Now, here too, leadership proved inadequate because the unionist leader in Northern Ireland who had signed the Agreement, Brian Faulkner, was repudiated by the other Unionists, just as Gormley had been repudiated by his members, and the other Unionists said he had sold out Unionist principles. At Westminster, the Ulster Unionists, who had hitherto been part of the Conservative Party, they opposed the Agreement and declared their independence from the Conservatives. If you look at that list of Conservatives, I think 11 of them were Ulster Unionists who were separate in 1973. These Ulster Unionists formed a new coalition which they called the United Ulster Unionist Coalition and were determined to fight the Sunningdale Agreement. Now, this increased the problems for the Government because those Unionists who supported the Agreement, led by Faulkner, had not, as it were, got their act together for any early election, so it meant that an early election would almost certainly lead, as it did, to success for the Unionists who were opposed to the power-sharing agreement and that would be destroyed, and that was one reason why…really inhibiting Ministers against an election.

You will not be surprised, after all this, to hear that Edward Heath said this was going to be the worst Christmas since the War, and if I can work this machine, you can hear Edward Heath saying it, and I think this does reveal his method of speaking at people perhaps rather than to them.

[Audio plays]

“As Prime Minister, I want to speak to you simply and plainly about the grave emergency now facing our country. Jobs will be in danger, and take-home pay will be less. We shall have to postpone some of the hopes and aims we have set ourselves for expansion and for our standard of living. We shall have a harder Christmas than we have known since the War.”

You may say it is being so cheerful that kept Heath going…

In the New Year, in 1974, there was renewed talk of an early election, helped by one opinion poll which showed that the Conservatives were ahead for the first time for three years. Perhaps in response to this, the Trade Union Congress made an attempt to settle the problem of the miners. They said to the Government that if the miners were allowed extra money to break stage three, the other unions would not use this as an argument in their own negotiations. The Government rejected this, and it was blamed for it after the Election, but the TUC could not prevent any award to miners being used in that way, and in any case, most workers had already settled under stage three, and those that remained were not in a very powerful bargaining position. What the Government thought was a formal commitment that no other union would break stage three, indeed the Conservative Party would probably have insisted on this, the TUC could never have been offered such a commitment because it had no power over individual unions, which remained autonomous organisations. But perhaps, nevertheless, the Government should have accepted the offer, challenging the TUC to deliver it. In her memoirs, Margaret Thatcher, who was Education Secretary in the Heath Government, she argued this was a policy to follow, though she did not say it at the time, but she said so later. She said that “We might have done better to accept this offer and put the TUC on the spot. Either the Government could have triumphed by forcing the unions to accept wage restraint, or it would have an excuse for a tougher line against the unions.” But the trouble is, the Government was beginning to believe that agreements with the unions were not actually worth very much. Nevertheless, that may be the key point at which they missed the last chance of an agreed settlement.

Heath was now saying to the miners: “If only you will accept stage three, we will find a way to give you a bit more under the relativities idea,” and the Pay Board said that they would consider all that if only the miners would resume work. But the miners were saying we will not accept stage three, and so there was a deadlock, and the Election was seemingly a means to resolve the deadlock – but how? If, as was likely, the miners would get more money under the relativities procedure, would that or would that not break stage three? And in any case, why did you need an election to resolve that question? The factors causing the crisis would still be there after the election – the shortage of oil, and the consequent need to pay the miners more. Perhaps an election might give the Government more leeway to break the guidelines of stage three and give the miners more, but the Government was going to be calling the election in defence of stage three and being fair to workers who had already settled under it, so what was the point of the election?

Now, perhaps if you had had the Fixed Term Parliament Act and the Prime Minister could not have dissolved and he could not have called an election, perhaps there might have been a settlement – who knows?

But the crisis now worsened. The new Energy Secretary, Lord Carrington, made a foolish speech in the middle of January, saying the three-day week was not causing as much of a loss of production as had been feared, since coal stocks were in a reasonably good state, and that Britain could now move, he hoped, to a four-day week. The miners’ response was to call for a ballot on an all-out strike, and this of course ended all talk of a four-day week, and on the 24th of January, they voted 81% for a strike.

One Conservative Cabinet Minister then said, “The miners have had their ballot. Perhaps we ought to have ours.” On February 7th, Heath announced an election for February 28th. He remained, I think, reluctant to the end, and for this reason, he did not fight a union-bashing campaign. He might have done better perhaps if he had. He said the main reason for the election was the oil price rise and the very serious economic situation it created, and so the central message came to be very muddled, especially as, the same day as he announced the election, he said the miners’ claim would be examined by the relativities machinery of the Pay Board and any award would be backdated to March 1st. So, the election was very ironic. It was called in defence of a statutory incomes policy that had been explicitly repudiated by the Conservatives in 1970, and it was unclear how the election would help settle the problems which that policy had aroused. What the Conservatives were in fact doing was to seek a mandate to pay off the miners, to do what they were not prepared to do before the election, and did not that make nonsense of the whole policy? Because if the miners would be paid off afterwards, why not pay them now? The election was really about who would the country choose to pay off the miners. The Conservatives could argue at least they were offering a quasi-judicial and fair way of ending the strike, rather than a concession to brute force, as Heath put it, “an orderly, rational, not off-the-cuff way”, but the Pay Board was widely seen as a fig-leaf for the Government’s decisions, for political decisions. So, the answer to the question “How are you going to settle the strike?” was not “We are going to stick to what has been offered,” but “We are going to pay the miners more but not until we have won the election.” It may be that such a deal would not have been acceptable before the election because the Conservative Party would not have accepted it.

But Harold Wilson was able to caricature this approach when he said, the day after the election was called: “For the first time in history, we have a general leading his troops into the battle with the deliberate aim of giving in if they win.”

But nevertheless, when the election was called, Labour feared they would lose, and they begged the miners to call off the strike. Gormley wanted the strike postponed till after the election, but he was again defeated by his Executive, by 20 votes to 6. The noted psephologist David Butler told his friend Tony Benn the election would result in a Conservative landslide, and one Labour MP at the time told me, some years later, he feared he would lose his seat when the election was called.

But, and perhaps not surprisingly, the Conservative position gradually began to unravel during the election campaign. The first problem was caused by Enoch Powell, who was at that time a dissident Conservative backbencher but one of the most popular politicians in the country. When the election was called, he wrote a letter to his constituency chairman denouncing it as “essentially fraudulent”, because he said, “For the object of those who have called it, it’s to secure the electorate’s approval for a position which the Government itself knows to be untenable, in order to make it easier to abandon that position subsequently.” Not wholly unfair I think… “It is unworthy of British politics and dangerous to Parliament itself for a Government to try to steal success by telling the public one thing during an election and doing the opposite afterwards.” And to rub salt into the wound, Powell said he could not, in any case, ask electors to support policies “…which are directly opposite to those which we all stood for in 1970, and which I have myself consistently condemned”. So, he said he would not be standing again as a Conservative candidate. Later in the campaign, without being explicit, he recommended a Labour vote, on the ground that Labour was offering a referendum on Europe, which would enable, he hoped, Britain to leave the European Community. It is funny how these issues keep coming back…

On the 26th of February, two days before the election, Powell said he had cast a postal vote for Labour, and he said, “It would have been strange indeed if I had voted in any other way than the way in which I have advised the country to vote.”

Bringing Europe into it shows the tremendous difficulty of trying to confine a campaign to a single issue, though, as I have said, I think the single issue itself was also unclear. Wilson argued, throughout the election, that Heath was hoping them miners’ dispute would distract voters from what he called the real issues – prices, high mortgage rates, the collapse of the housebuilding programme, and Europe, on which he thought the Conservatives were not in a strong position.

Now, the election was called, as I have described, in an atmosphere of something of a crisis and some bitterness, and it was expected the campaign would be confrontational and unpleasant, but instead, it proved remarkably good-humoured. The miners’ issue gradually receded from the forefront of the campaign and the atmosphere of crisis and confrontation gradually dissolved. Roy Hattersley, who was a Labour Shadow Minister at the time, said, in three days of canvassing, only one constituent had referred to the miners. The ban on television after 10.30pm was ended. The weather was good, and people found themselves rather enjoying the three-day week. The railway strike was called off, and the miners, wisely, reduced the scale of their picketing. This made some people think perhaps there was no crisis at all and the election had been called for nothing. As the campaign continued, Wilson, in response to the opinion polls, laid much greater emphasis on prices because polls showed that was a key issue for swing voters. There had been a 50% increase in food prices since 1970 – inflation was going through the roof. The polls also showed, admittedly, the public were in favour of the statutory incomes policy and they did not blame the Government for the rise in prices but world factors, so the Conservatives had some hope there.

But it is interesting that, in his novel “Sweet Tooth”, published a couple of years ago, Ian McEwan, writing on this period, said: “People had stopped worrying about the miners and who governs and had started worrying about 20% inflation and economic collapse and whether we should listen to Powell, vote Labour and get out of Europe.”

Now, in the week before the election, there were three further blows for the Conservatives. On the 21st of February, a week before the election, the Deputy Chairman of the Pay Board said that miners’ pay had been wrongly calculated, and that, on the proper measure of calculation, their wages were not above the national average for manual workers in nationalised industries but 8% below. Harold Wilson smartly turned this to advantage. He heard about it in the early evening, campaigning in Essex, and he quickly rushed back to the television studio to make the point, and by the time the Conservatives could, it was too late. The point had got into the public consciousness, and it made the Government of course appear incompetent. But you may say, well, any Government can make a mistake. What made it worse was it seemed to highlight the fact, as people believed, that Government was unwilling to settle and was looking for any excuse not to settle when the means for settlement were available.

The second blow was on the 25th of February, three days before the election, when monthly trade figures showed a £383 million deficit for January, the largest ever recorded. That brought home to people’s minds that all the economic indicators were appalling. Prices were rising at over 20%, unemployment was rising, economic growth was falling, with a heavy balance of payments deficit likely.

So, you may say what is remarkable about the February 1974 Election, from that point of view, is not that Heath lost but that he came so near to winning in those circumstances.

The third blow came on the 26th of February, two days before the election, when the Director-General of the CBI, talking as he thought to a private meeting, where he thought his remarks were off-the-record, said that the Industrial Relations Act had soured the industrial climate and he would like to see it repealed. That was reported in public. And it is fair to say other CBI leaders had said the same before.

Even so, on the day of the election, all the opinion polls indicated a Conservative lead of between 2% and 5%, but also a high Liberal vote. Wilson expected to lose, and he thought, if he lost a second election, he would have to resign as Leader of the Labour Party. He was staying at a hotel in Liverpool, near his constituency, and he had prepared a statement resigning as Leader, and he had prepared a secret getaway by helicopter so he would not have to face the media after what he assumed was a second consecutive election defeat. He, with all his psephological knowledge, was as surprised as anyone by the result. It is one of those rare elections – perhaps they will become more frequent – where the campaign made a tremendous difference. The conventional wisdom till then was the campaign did not matter, that people had made up their minds long before, and that I think was true in 1945 and the elections of the 1950s, when parties divided on a tribal basis. It was not true anymore in the era of party volatility. The February 1974 campaign was decisive and the polls showed that more people switched their votes than in any previous election.

If we go back to the result, the turnout, 78.7%, was the highest since 1951, and only in 1950 and 1951 has turnout been higher since the War. There was a very swing against the Conservatives, 0.8%, but 40 seats changed hands, and the Conservatives, as you can see, they won more votes but fewer seats than Labour. But in a sense, looking at the swing is not the key thing. Both the major parties had lost votes. The Conservatives had their lowest vote share in the twentieth century, except for October 1974 and 1997, and before that election, it was the largest fall in votes for any Government between one election and the next, except for 1997. The swing against the Conservatives was particularly large in the West Midlands, which had swung heavily to the Conservatives in 1970. In Enoch Powell’s seat, the swing against the Conservatives was 16%, not 0.8%, and elsewhere in the West Midlands, between 5% and 10%, and that was a much greater regional swing than anything seen since the War. Enoch Powell put it pithily. He said: “I put him in and I got him out.”

Now, the Labour Party, in a sense, won the election, but if you look at the previous thing, you see that they actually lost nearly 6% of their vote from 1970 when they had lost the election. They had lost around one-seventh of their vote from 1970 when they had actually lost the election.

Obviously, the key factor is the surge of the Liberals. Now, their vote, in a way, was even higher than shown there because they did not fight every seat. They fought 517 seats, and their average vote per candidate was 24%, nearly a quarter, and you may say that is a strong argument, and certainly they thought so, for proportional representation – they got a fifth of the vote in total and hardly any seats. With PR, they would have got 120 seats. They had become a national party again, for the first time since the 1920s, and in the next election, in October 1974, they put up candidates in every seat, so there was the theoretical possibility of a Liberal Government for the first time since the 1920s, and proportional representation back on the agenda.

Then the Nationalists were back, Scottish Nationalists, 22% of the Scottish vote, higher than they got in 2010, when they got 20%, and in October, they were to get 30% of the Scottish vote. They were more popular then in Westminster than they were in 2010.

The Ulster Unionist Coalition got 11 of the 12 Northern Ireland seats on 51% of the vote and that finished off the Sunningdale Agreement, which collapsed in the summer.

Now, after the election, Heath did not resign. He was entitled to stay on, indeed, to meet Parliament. But what he did, he called the Liberal Leader, Jeremy Thorpe, to Number 10 and offered him a coalition, and he said the Conservatives and Liberals agreed on a statutory incomes policy and on Europe, so there was a mandate for that from the country he said, and he also said the Conservatives had won more votes than Labour. Thorpe replied, “Well, if votes are the criterion, are you a convert to proportional representation?” which of course Heath was not. His mandate argument was absurd. Polls showed most voters did not know where the Liberal Party stood on these issues, but in any case, half the voters were against British membership of the European Community, including many who voted Liberal. If the mandate argument had any meaning, surely it went against Edward Heath because he had called for a mandate and failed to achieve it. You may say it is not clear what the voters meant by the result, but one thing they clearly did not mean, I would have thought, was that Heath should continue as Prime Minister. In any case, a coalition with the Liberals would not have yielded a majority. Now, when Thorpe said there has to be progress on PR if we are going to join you, Heath said, and he could not do any more, he would set up a Speaker’s conference with purely advisory powers and take account of that, and Thorpe said that was not enough.

Now, the Conservatives also offered the whip to seven of the 11 of the Ulster Unionist MPs. They were not going to offer the whip to Ian Paisley, who had opposed the Sunningdale Agreement really very violently. But the Leader of the Ulster Unionists said you have got to offer it to all 11 of us or nothing, so that too collapsed.

Now, while all this was going on, Wilson was waiting, very shrewdly, saying he would not make any deals with anyone, and his Deputy, James Callaghan, said “Let Heath swing – he can’t stay,” and you can hear Harold Wilson’s rather clever statement I think, made after the election.

[Audio plays]

“I’m returning immediately to London by air and I have summoned a meeting of my senior parliamentary colleagues for this afternoon.In the situation the country is facing, it is of paramount importance that a Government be quickly formed to get the country back to full-time work in order to be able to deal with the pressing economic problems which face us both at home and abroad. A month ago, the Conservatives had a working majority and nearly a year and a half to go. It is manifest that they have not received the mandate they sought for continuing their existing policies, that the whole country is anxious about the state of the nation, and this must mean that the new Government must be at work as quickly as possible.”

When Heath resigned, Wilson formed a minority government and, as I said earlier, there was a second election in October which gave them a narrow majority.

Now, some people say Heath was unlucky – if only he had called the election three weeks earlier, as many Conservatives wanted, he could have won. I think that is by no means clear because people might then have said he was seeking a confrontation with the unions, who attracted much sentimental sympathy. There would have been I think fewer Liberal candidates three weeks earlier. If they had not got their act together yet, there had have been about 400 rather than 517 who fought. But the more important advantage you might have got from an early election was it might have prevented the strike if the election had been held before the strike ballot was called because if the strike had then been called, it would look like an interference with the democratic process and would have backfired on Labour. You may argue, Heath’s tactical mistake was to allow the National Union of Mineworkers to call their ballot first.

But it seems to me this is not the point that if he had won the election, would he not have had to do what Wilson did? Wilson made an offer to the miners, in excess of stage three, which was accepted and they went back to work. Perhaps the voters failed to support Heath because they noticed the incoherence of the “Who governs?” approach, and if so, that incoherence would have been just as noticeable three or four weeks earlier.

And of course, the subsequent history of the Wilson and Callaghan Governments showed that regulating the economy through an incomes policy led again to that cul-de-sac because it imposed on the trade union leadership obligations which they were not only unwilling but perhaps also unable to meet. They saw their role not as one of helping the Government run the economy, but of getting the best they could for their members, and if they failed, they would be undermined by militants who could do the job better. But more important, I think, that the social solidarity which alone could have sustained an incomes policy was being undermined by the very prosperity and affluence which both Conservative and Labour Governments had championed, and the Heath Government, like its Labour successor, was defeated not by collectivism, not by the solidarity of the unions, but by a new rampant individualism.

Now, when Heath tried to persuade the unions to accept the stage three proposals, he said: “Think nationally. Think of the nation as a whole. Think of these proposals as members of a society that can only beat rising prices if it acts together as one nation.”

If Churchill or Attlee had said that in the ‘40s or early ‘50s, I think people would have respected it. By the 1970s, it was greeted with derision because each group was out for itself. It was the world of “I’m alright, Jack,” quite different from that in which Heath had grown up. And in any case, a Conservative Government committed to an incomes policy would always be outflanked by the Labour Party, whose ties to the unions would also make it say “We can get you a better deal with a Labour Government,” and the Conservatives therefore were repelled by the increase in State power and the links with the unions which a statutory incomes policy involved, so they looked for an alternative method of regulating the economy, which did not rest upon the consent of the trade unions, and they found it in 1974/5, a revolution in Conservative thinking, led by Keith Joseph and Margaret Thatcher, the philosophy of economic liberalism and monetarism. So, the policy on which Heath fought the election was almost certainly unviable, and I think even if he had won the election, he would either have got into a cul-de-sac or been forced to abandon it.

The Labour Party, I think, drew the wrong lessons from 1974. It was not only the Conservatives who lost the election, but also the right-wing of the Labour Party, the Social Democrats, under Roy Jenkins, who had resigned from the Shadow Cabinet in 1972 in protest at Labour leftward movement. He had assumed that Labour fighting on a left-wing programme would lose the election, and he says in his memoirs that: “1974, according to my strategy, was the year in which temporising Labour Party leadership was due to receive its just reward in the shape of a lost General Election,” so the left would be weakened and Roy Jenkins’ moment would have come.

The left saw this as a reversal of 1926, a reversal of the verdict of the General Strike, and it seemed to show that Labour could win an election on a left-wing policy. Tony Benn drew that conclusion. He said in his Diaries: “If the Labour Party wins the election on the slogan “Back to work with Labour”, then the balance of power in the Labour Party is absolutely firmly on the left, because one of the great arguments of the right is that you can’t win an election with a left-wing programme. If you have a left-wing programme and you win an election, then the right will have lost that argument and that will be a historic moment in the history of the British labour movement.”

Now, as we have seen, Labour won the election only in the sense they lost fewer votes than the Conservatives, but the system misled them because they won more seats than the Conservatives and so it seemed to show that Labour could win on a left-wing programme, and it led to 1983 and Michael Foot, which tested Benn’s theory one could say to destruction really.

February 1974 then is a defeat not just for Heath but for the right-wing of the Labour Party, and I think you can see the roots of the SDP breakaway in that election defeat of the right-wing. The Labour Party ignored the fact that, even though Heath was defeated, every single opinion poll, without exception, showed that the voters believed the trade unions to be too strong and not too weak, to have too much influence and not too little. But the Labour Government proceeded to give the trade unions extra privileges, despite the fact that every poll showed they already had enough. These privileges were given under the theme of the social contract. But the Chief Secretary of the Treasury in the Labour Government, Gerald Barnett, was later to say in his memoirs, “To my mind, the only give and take in the contract was that the Government gave and the unions took.” That led to the Winter of Discontent, after a further wave of public sector strikes, in 1978 and 1979.

One of Wilson’s advisors said in his diaries, “The public sector unions elected Margaret Thatcher in 1979. Indeed, she subsequently said thank you to them in her own individual way.”

One commentator said the Winter of Discontent was “the final crisis of democratic socialism” because the decline of social solidarity was a much greater threat in the long run to the left than to the right. The Conservative response could be individualism, Thatcherism, if you like. More difficult for a party of the left to accommodate to the decline of the traditional loyalties and community feeling – it took 20 years before Blair was able to accommodate the Labour Party to that.

So, the failure of Heath convinced many Conservatives that incomes policy could not work, but it also convinced the British people that the trade unions would have to be curbed. Margaret Thatcher’s success was built on Heath’s failure. But in every other sense, Heath was the antithesis of Margaret Thatcher because Heath thought to resolve Britain’s problems within the constraints of the post-War consensus, by preserving in particular full employment. Margaret Thatcher, unlike Heath and all of her post-War predecessors, was prepared to abandon that goal, and hers was the first Government since the 1950s to govern against that goal. Thatcherism proved a response to a constituency which the post-War Conservatives, and Edward Heath in particular, had ignored – it was a Conservative constituency but ignored by them. Heath was accused of being a corporatist, of looking to the large organisation – the trade unions and large companies. But what about those who were not represented by large organisations – the self-employed, those on fixed incomes, or pensioners – how were they to protect themselves against inflation? They were the people the Conservative Party ought to be defending, people with little or no capital of their own who feared losing what little they had. They formed the bedrock of Thatcherism to protect themselves against rising prices when they did not have strong unions to represent them. They had been ignored by the post-War settlement, which was a settlement of the big battalions, and these forgotten people were those who helped remove Heath because they’d been patronised or ignored by previous Conservative leaders.

It was well summed up by Nigel Lawson, who said that: “Margaret Thatcher was unusual for a Tory leader in actually warming to the Conservative Party, that is to say the Party in the country rather than its Members of Parliament. Harold Macmillan had a contempt for the Party. Alec Home tolerated it. Ted Heath loathed it. Margaret genuinely liked it. She felt a communion with it.”

Heath was the last Conservative Prime Minister to seek to uphold the post-War settlement. He was, as one commentator suggested, the last loyal signatory of the 1944 Full Employment White Paper, by which Governments promised to secure a high and stable level of employment in return for wage restraint, but he was fighting against an ineluctable tide of opinion which would have engulfed him even if he’d won in 1974. Heath, I think, strained the post-War settlement beyond its natural limits and it snapped in twain, and I think we are still living with the consequences, and I suggest therefore, and conclude, that we still live in the shadow of the defeat of Edward Heath in February 1974.

© Professor Vernon Bogdanor, 2015

GENERAL ELECTION 1970

Seats % Votes

Conservatives 330 46.4

Labour 287 43.0

Liberals 6 7.5

Others 7 3.1

Total 630 100

Turnout. 72.0%.

GENERAL ELECTION: FEBRUARY 1974

Seats % Votes

Conservatives 297 37.9

Labour 301 37.1

Liberals 14 19.3

SNP 7 2.0

(22% of Scottish vote)

Plaid Cymru 2 0.6

(10.8% of Welsh vote)

Northern Irish parties 12 3.1

Others 2 0.4

Total 635 100.0

Turnout 78.7%

Swing 0.8%

Part of:

This event was on Tue, 20 Jan 2015

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham College plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login