Gresham and Defoe (underwriters): The Origins of London Marine Insurance

Share

- Details

- Text

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

This lecture explores the astonishing history of marine insurance underwriting in London by reaching back to Lombard Street in the 1400s, revealing the underwriting activities of some well-known characters, explaining the origins of the Lloyd’s market, and shedding light on this critical industry’s 300 years of world leadership from London.

This lecture will be followed by a reception, sponsored by Z/Yen Group.

Download Text

13 March 2014

Gresham and Defoe (underwriters):

The Origins of London Marine Insurance

Dr Adrian Leonard

Marine insurance is very old. It has a low profile – bankers seem to take all the heat – but it has been an important part of London’s international financial services offering for centuries. Marine insurance arrived in London more than

250 years before Edward Lloyd started his Coffee-house, and about 150 before the Royal Exchange was officially opened by Queen Elizabeth. Underwriters were laying down lines in London at latest by the 1420s, but still, marine insurance is quite a bit older than that.

In the hour ahead I am going to tell you about the origins of marine insurance in Italy, its spread to the great port cities of north western Europe in the late middle ages, and how it came to be that London began – and continues – to dominate the world in this important commercial sector. Along the way we will meet some familiar characters, we will learn about great, ruinous catastrophes that knocked out some who were over-exposed, and – perhaps most interesting – we will see that the way marine insurance is done in London really hasn’t changed very much over the many centuries this talk will cover.

The earliest really solid evidence of marine insurance is found in the archives of the city states of Italy – Genoa, Florence, Venice, and the rest. Merchants of the fifteen hundreds called this region Lombardy.

In the thirteen and fourteen hundreds, Italians were the masters of world trade. The Germans of the Hanseatic league controlled the lucrative business of bringing goods from the Baltic Sea region to the rest of Europe, but it was Italian merchants, with their Mediterranean access to the luxury goods from Asia and North Africa, who set the standards.

This was no business for the faint of heart. Trade in the early age of sail fundamentally precarious, unpredictable, and fraught with perils. Merchants often had no choice but to bear the dangers – to ‘run the risk’ – of naked threats. At worst, these could mean the complete destruction of a season’s invested capital, spelling ruin for an individual merchant-adventurer.

The rage of the oceans often caused the total loss of ships and their cargoes, or inflicted extensive damage before goods reached markets. Such natural perils were known in early policies as of those of maris, the seas. The violence of men, gentium, came in the form of warships, pirates, and privateers. These could present an even greater danger, especially in wartime, when human risks to trade were recurrent and grave. At their heights, enemy onslaughts against seaborne trade could endanger the whole commerce of a country, imperilling is military success, and potentially even, its independent survival.

Italian merchants began to deal with this very real problem – and we need only to think of the plight of Antonio, the Merchant of Venice, to see how real it was – at some point in the late 1200s, or perhaps the early 1300s. Men like Antonio invented marine insurance. Research undertaken long ago by historians, including the Italian Enrico Bensa in the 1880s and Florence Edler De Roover in the 1930s, leaves little doubt about these origins. Genuine insurance was a product of the late medieval commercial revolution, which occurred in Italy during the half-century from 1275 to 1325. This “revolution” also saw the development of bills of exchange and double-entry bookkeeping, both of which, like marine insurance, remain in use today, pretty much unchanged.

In inventing marine insurance, Lombard merchants figured out the most effective and efficient means of minimising the impact of the threats to trade presented by the seas and by men. The financial instrument was designed to spread the

cost of losses at sea as widely as possible amongst the merchant community, and thus among the end-consumers of internationally traded goods. It worked remarkably well.

The idea wasn’t entirely new, even then. Earlier financial instruments provided merchants with relief if – in the words of this English policy of the 1550s, “God’s will shall be that their ship shall not well proceed”.

Called “sea loans”, the predecessors to marine insurance were very simple. Merchants borrowed money from an investor, and if their ship sank, or their goods were lost, the loan was forgiven. Sea Loans are mentioned in the writings of Demosthenes, an exact contemporary of Aristotle. In an early example of state intervention in markets, the Byzantine Emperor Justinian fixed the price of sea loans at twelve per cent in the year 533 AD. Regulations governing Sea Loans were set out in Emperor Basil I’s Basilica, and in Roman law, which calls them nauticum foenus.

Variations on the structure such as the Italian cambium nauticum had a third, and perhaps more important function. They allowed merchants to borrow money at interest, which was prohibited under Catholic usury laws. The interest on the loan was disguised as a risk premium, and the scholars of the church deemed this sort of transaction acceptable in the eyes of the Vatican.

So much for ancient history. These early instruments of risk transfer all had the same drawback: the buyer also had to be a borrower. Marine insurance disconnected insurance from borrowing. As trade expanded, marine insurance took off like a celebrity rumour in the twitter-sphere. For example, in just three weeks between 21 August and 15 September of 1393, the Genoese notary Theramus de Majolo was involved in more than eighty insurance transactions.

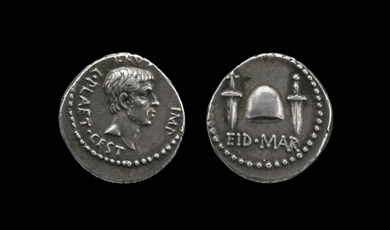

Already by this time, many of the contemporary practices of marine insurance were adopted and perfected. Multiple underwriters participated in each policy, assuming a proportion of the sum insured. This spread the risk broadly. The

policy on the screen shows this: each participating insurer has signed his name below the policy, making him and ‘under-writer’, or, in a different language, a ‘sub-scriber’. These early underwriters charged a premium which was expressed as a percentage of the sum insured, and which varied based on the characteristics of both the vessel and the voyage to be

insured. These rates were adjusted according to the loss experience, and to various threats related to a specific voyage, such as the season, or the activity of corsairs. The underwriters specified the broad perils which were to be insured under the policy, and included in the contract the name of the insured vessel, the nature of the cargo, and the details of its voyage. Policies were often arranged by intermediaries. Most of the underwriters were merchants themselves, although by the fifteenth century wealthy investors were also taking lines on insurance contracts. Insurers’

salvage rights were established in principle, if not in law. So too was the insurers’ preferred recourse to arbitration, should disputes arise. You can see that this policy, from 1555, specified that the parties agreed, should a dispute arise, “to remit it to honest merchants, and not to go to law”.

London was a relatively unimportant trade city in the early fifteenth century, which is perhaps why the earliest accessible map we have of the city is from 1572. Notably, Lombard Street was clearly established at this time, but one hundred and fifty years earlier, much of her trade was controlled by German merchants of the Hanseatic League, who were to

be expelled a century later (with the support of Sir Thomas Gresham). Italian merchants handled the trade with Southern Europe. The Dutch were not yet important.

It is in the transactions of those Italian merchants – the traders of Lombard Street – where we find the earliest evidence of marine insurance in London. The records of businesses and the courts have preserved the clues.

The prize for the oldest surviving record yet found must go to an entry in the Plea Rolls of the City of London. In 1426, Alexander Ferrantyn, a Florentine merchant resident in London, took his insurance dispute to the Lord Mayor and Aldermen. He had purchased insurance from some other resident Italians.

Ferrantyn’s case was heard in the Guildhall. He was refused a claim for his vessel, the ‘Seint Anne of London’, which was

carrying a cargo of wine to England from Bordeaux. Both the vessel and the cargo were covered for £250 by seventeen Italian merchants resident in London. The assets had been seized by Spaniards, but Ferrantyn, through an agent, had

managed to buy-back the vessel and cargo, which the privateers – the licensed pirates of this age of plunder – had sold to Flemish merchants.

The policy specified that the ‘order, manner, and custom of the Florentines’ was to govern the contract. Ferrantyn asked his insurers to pay up, citing ‘the law merchant’, and the clause about Florentine custom. Clearly, in these early days

of London insurance, accepted local practice was undeveloped, or carried little weight. However, we will see later that London practices went on to govern much of the world’s marine insurance,.

The disputing parties claimed respectively that Florentine custom required the indemnity to be paid in this circumstance, and that it did not. Both parties promised to produce notarised testimony from the Italian city which would outline

the prevailing local custom. So confident were the defending insurers that they paid into the court the disputed £250, plus £100 as surety.

Ferrantyn’s insurance-buying was not isolated. Filippo Borromei & Co. of Bruges and London was just one bank of many in the extensive network of the eponymous Italian merchant-banking family. Its surviving ledgers show that the London branch of the bank made regular and routine insurance transactions in London in the 1430s. For example, on 10 January 1438, a clerk in the London office recorded a transaction with its parent, the Bruges bank, as follows: ‘credited to their conto a parte [their account], for cloth, for 50 pieces of Essex streits [a broadcloth one yard wide], bought for £st 31.5.0; insurance at £st 1.16.8’.

The identity of the underwriters of these policies has, in some cases, survived. The Borromei ledgers refer to ‘insurance underwritten by us on the cargo and ship of Giovanni Tanzo’, indicating that the bank itself would sometimes assume

insurance risk. This was typical – buyers of insurance were often sellers, too, The bank’s Bruges ledger of the same

year names the underwriters, which include three individuals and one partnership, all of which appear to be of Italian extraction. The seventeen London merchant-insurers named as defendants in the Ferrantyn case include two

each who were natives of Venice, Genoa, and Florence, and eleven who are unidentified, but whose surnames also indicate Italian origin.

In 1480, two of London’s leading Italian merchants took an insurance concern to the Mayoral court. Antonio Spynule, a resident Genoese merchant, and his English attorney appeared before the Lord Mayor and aldermen. Spynule wished simply to attest to the receipt of an insurance premium of £6.13s.4d from the local merchant Marco Strozze. The policy by this time is described as a ‘bill of assurance’, but it had been lost.

It is safe to conclude from this evidence that the community of Italian merchants in London insured regularly in the early fifteenth century, and did so primarily amongst themselves. They comprised London’s earliest generations of merchant-insurers, and their practice was typical of its time.

As soon as there was insurance, there was insurance fraud. A story in the Great Chronicle of London shows that dishonest buyers would sometimes attempt to defraud underwriters. The anonymous chronicler recounted the story of a rogue trader who, at some point before 1509, thought

To stuff ships with false, crafty balances

Such as blocks & stones, and counterfeit dalliances

And after, insure the said ships with their freight

For great sums, till they come on the height

Of the ocean, and then cause them to drown

That the insurance, might for nought be paid.

Notwithstanding the terrible quality of the verse, the passage shows that underwriters have always been in imperilled by the unscrupulous – although in this case, according to the chronicler, the fraudster was caught.

A similar fraud was recorded by Samuel Pepys in his diary. A trial was held at Guildhall in 1663, before the King’s Bench. According to Pepys, Lord Chief Justice Hyde, with ‘all the great counsel in the kingdom in the case’, heard how an unnamed ship’s master over-insured a ship laden with bogus cargo worth, at most, £500. But a notorious deception was underway. The cargo was actually ‘vessels of tallow daubed over with butter, instead of all butter’. The criminal

abandoned the ship, to let it flounder on the rocks at low tide. He refused the aid offered by nearby ships’ pilots who came to his assistance. The judge found in favour of the insurers, one of whom had salvaged the ship, uncovered the

fraud, and later repaired the vessel for just six pounds.

Much of the sixteenth-century evidence of insurance in London survives in policies preserved in the records of the High Court of the Admiralty. They are in a sorry state, as the examples pictured show. The jurisdiction of this court varied dramatically over the years, but was at its height in the Tudor century.

The earliest policy I have found in these records was underwritten in 1547. It reveals much about insurance in our city at this date. The policy is written in Italian, but the buyer – one John Brook – and the underwriters, William Maynard

and Thomas Lodge, clearly are not. It was common, we learn from other evidence, for policies at this time to be written in multiple languages, for the convenience of merchants involved in multinational trade. In this case the

cargo, a shipment of grapes from Crete, was being transported from the island to London on board the Venetian ship Santa Maria, which may explain the language of the policy. The insurance was to cover only the portion of the journey from Cadiz.

Of particular interest is the clause which governs the jurisdiction of disputes. We will remember that the Ferrantyn policy was governed by the customs of Florence. 121 years later, this policy states clearly that ‘it is to be understood this present writing hath as much force as the best made or dicted bill of assurance which is used to be made in this Lombard Street of London’. The particular custom which was to govern the policy was that of the merchants of Lombard Street. The phrase ‘dicted bill’ suggests the validity at this time of verbal contracts of insurance, and that they carried the full weight of customary law.

What was this mutable, customary law? It was the Law Merchant, the unwritten code of practice followed by merchants. It had some regional differences, as we have seen. It set out the rules of the game for insurance buyers and underwriters, such as those upon which the Farrantyn case turned. John Weskett, an insurance underwriter, member of Lloyd’s, and an apparently irascible chap, wrote a book in 1781 called A complete digest of the theory, laws, and practice of insurance. In it he described the Law Merchant, which was clearly still important in his day.

Because it changed from place to place, insurers usually named in their policies the location-specific body of Law Merchant which was to govern the contract. By examining these statements, we can learn something about the importance of London as an underwriting centre.

We saw that in 1547, a London policy cited Lombard Street. Another policy, issued in 1552 to insure the Florentine merchant Robert Ridolfi (better known for his plot to assassinate the queen), also mentions only Lombard Street. However, a sort-of expert opinion which accompanies it states that ‘the use and custom of making bills of assurance in the place commonly called Lombard Street of London, and likewise in the Bourse of Antwerp, is, and time out of mind hath been, among merchants using and frequenting the said and several places...’ This hints that Antwerp custom was still being taken into account by the courts.

A further policy, drawn up in 1555 to insure the Portuguese merchant Anthony de Salizar, makes the Antwerp connection directly. It states that ‘this assurance shall be so strong and good as the most ample writing of assurance which is used to be made in the street of London [that is, Lombard Street] or the bourse of Antwerp.’ Meanwhile, a 1566 policy underwritten in the Flemish city refers to London’s authority. It seems that merchants were flexible as to the body of Law Merchant which was to apply in these early days. Such flexibility allowed the rules to change with the times.

The next major change in the clause happened in the late 1570s, and was the responsibility of a man named Richard Candeler. An agent of Thomas Gresham, Candeler began to loom large in London’s vibrant insurance market in that decade. He was granted a Royal patent which gave him the exclusive right to the ‘making and registering of all assurances, policies and the like upon ships and goods going out of or into the realm, made in the Royal Exchange or any other place in the city of London’.

Candeler opened his office in the Royal Exchange. Uniquely, one could enter his office from inside the exchange, whereas all the others had doors only onto the street. Surviving policies underwritten while his office – the Office of Assurances – was in operation, state that the policy had the force of ‘the best & most surest policies ... to be made in Lombard Street, or now within the Royall Exchange in London’. That’s the phrase written in secretary hand in 1582, in

the top excerpt on the slide. Candeler, it seems, was setting out his authority.

When the Office of Assurances faded from the picture, sometime after the Glorious Revolution of 1688, the clause changed again, to cite only to ‘Lombard-street, or elsewhere in London’, as shown in the second excerpt. However, the authority of the custom of the Royal Exchange was permanently to return, even before Lloyd’s moved there in 1771. A

policy underwritten in New York in 1760 states ‘That this Writing, or Policy of Assurance, shall be of as much

Force and Affect as the surest Writing or Policy of Assurance heretofore made in Lombard-Street, or in the Royal Exchange, or elsewhere in London’. This exact clause is still included in marine policies issued by Lloyd’s and other London marine insurers, as in the third excerpt. It appears in the sample ‘Form of Policy’ included as a schedule to the 1906 Marine Insurance Act.

At the risk of boring you with too much policy language, I would like to show you another impact of the standardisation of policies which occurred when Gresham’s agent, Richard Candeler, monopolised the drawing-up of marine insurance

policies. The Florentine policies from the late fifteenth century that I mentioned earlier specified that the policy insured these specific perils: ‘God, the seas, men of war, fire, jettison, detainment by princes, by cities, or by any other person, reprisals, arrest, [and] whatever loss, peril, misfortune, impediment or catastrophe that might occur’. It

is a fairly all-encompassing wording. But the policy on the screen now was underwritten two hundred years later than the Italian one I just cited, in Candeler’s office at the Royal Exchange in London.

Here’s a closer look. This 1582 policy bears remarkable similarity to the Florence policies. It insured the buyer against ‘the seas, men of war, fire, enemies, pirates, rovers, thieves, jettisons, letters of mart, & countermart, arrest, restraint, & detainments, of kings & princes, & of all other persons, barratry of the master and mariners, and of all other perils, losses, & misfortunes, whatsoever they be, or howsoever the same shall chance, happen, or come to the hurt, detriment, or damage, of the’ insured cargo or vessel.

Here are two more policies, the earlier underwritten for the well-known merchant Ralph Radcliffe in 1716, the later for the Baltimore Steam Packet Company in 1950, at in the Room in Lloyd’s. Perhaps you can predict what they say. Even in 1950, and beyond until the 1980s, London marine insurance policies insured against the seas, men of war, fire, enemies, pirates, rovers, thieves, jettisons, letters of mart, etc. etc.

But back to history. We can see from information in this document, and similar ones, that marine insurance was remarkably well developed in London long before Edward Lloyd opened his coffee house. When Candeler garnered his monopoly, he didn’t get it without fight. Men complained – particularly the brokers and notaries who had been established for some time as the people greasing the wheels of London marine insurance. They did what sixteenth century merchants usually did when they felt aggrieved: they petitioned the Lord Mayor. Some of their petitions survive, such as this one, in which the notaries public complain wryly that, should the patent be granted to Candeler, not only would they and their families starve, but that Candeler himself will be made into a sort of ‘Notary Private’.

Together the petitions tell us that in the 1570s roughly thirty brokers and sixteen notaries operated in London’s marine insurance market. The former group facilitated the introduction and interaction between buyers and sellers of insurance, and managed financial relationships. The latter drew up policies, kept registers of their details, and managed client

monies. However, merchants and their insurers sometimes dealt directly with one another, without the intermediation of third parties. In many ways, the division of responsibilities in the market, although it was smaller, appears to

have been much the same then as it is today. It does seem, however, that a century of dominance by the Office of Assurance knocked the notaries out of the insurance business.

The market was also physically similar. A record of insurance transactions made in 1654-5 survived until the late nineteenth century in the Rawlinson manuscripts at Oxford’s Bodleian Library. A transcription was published in 1876. The document is almost certainly the record of an underwriter. It shows that insurance policies were underwritten at

addresses including Bartholomew Lane, Crutched Friars, Mark Lane, St Helens, and Threadneedle Street, all within an easy walk, and within today’s London insurance district. I mention the transcription because the original is lost: I

learned, after two days of searching at the Bodleian Library, that this fascinating source has been missing since the 1890s.

Richard Candeler must have been familiar with marine insurance long before his charter, if only through his connections to Gresham. The latter was appointed royal agent in the Netherlands in December 1551. While there, he was tasked

principally with managing the monarch’s crown debt on the Antwerp bourse. However, he helped successive monarchs in other ways. One was to provide imported arms and armour to his kingdom – this was his primary private trade. In 1560, for example, he directed his local agent, one von Dorovy, to load gunpowder worth £9,000 onto several ships, and to get them insured. Gresham had £2,000 worth of the goods loaded onto each ship, but purchased insurance of only £1,000 for each. He asked his masters for naval vessels to convoy his the ships, but the request was declined.

The cost of this cover was not recorded, but on a later shipment of armour and saltpetre, sent the following year from Antwerp to London, the rate was 5% for the short voyage. It further seems that the Queen was sometimes risk-averse,

not wanting too much materiel to go on the same ship. This led Gresham to send military kit to the English crown on his own account. When he did so, he was sure to get sufficient cover. ‘I have adventured upon my own head, one thousand pounds more in a ship, which I have caused to be assured upon the Bourse of Antwerp. So that I trust in God it shall most plainly appear to the Queen’s Majesty I have done my duty, and diligence,’ he wrote.

For a century historians have argued that insurance was not widely used in England before the eighteenth century. I disagree – a great deal of evidence suggests otherwise – but let us imagine for a minute that they are correct. Why would

Sir Thomas be such a serious purchaser of insurance? I have already shown that the merchants of the city, including the senior merchants, the Lords Mayor and Aldermen, were at least familiar with the instrument. Thomas Gresham came from a family of such people. More pertinently, though, he had an underwriter in his family. I have found the proof here – on a policy preserved in the records of the High Court of the Admiralty.

Taking a close look, we can see clearly – clearly, that is, depending on your palaeography skills – that the second underwriter here is John Gresham. The policy is dated December 1557, so the underwriter cannot have been Sir John

Gresham, Thomas’s uncle and the man to whom he was apprenticed, because the older man died in 1556. This John Gresham is also unlikely to have been Thomas’s elder brother, who was alive at the time, but was probably at his

estates in Norfolk, which he preferred to business life. That leaves his cousin, John Gresham, son of Sir John, who like his father was a Flanders merchant. This conclusion is strengthened by the fact the policy covers a shipment of goods from Malaga to Antwerp, the traditional trading territory of the Greshams. That said, I am no Gresham scholar, so I would be grateful to learn anything more about this man.

I would like to turn now to another familiar man, Daniel Defoe. Before he became a writer, in the years after the Glorious Revolution, his name was simply Foe, and he was a struggling merchant. Perhaps lured by the large rates on offer during wartime, he began to dabble in underwriting. It was a grave error. He lost everything in the business, after a great naval disaster which was described by contemporary parliamentarians as the ‘miscarriage of naval affairs’.

It was the summer of 1693. The combined Anglo-Dutch Mediterranean trading fleet of approximately 400 ships was much

larger than usual, because both nations had failed to despatch a Turkey fleet in 1692. On 27 June, at the First Battle of Lagos, near Cape St. Vincent at the south-west tip of Portugal, the convoy was overwhelmed by French privateers and

men-of-war. The twenty-one Anglo-Dutch naval escorts sent to protect them were elsewhere. Roughly three-quarters of the vessels escaped, but ninety-two or more merchant ships, valued with their cargoes at over £1,000,000, were captured or destroyed. Much of this loss was insured in London.

The event is known as the Smyrna catastrophe, after an important coastal trading city in Turkey. Insurance rates for vessels and cargoes in the Smyrna convoy had been high, at twenty-five per cent the day before the loss. Ironically, the price had fallen to twenty per cent on the day of the battle, and to ten per cent by 1 July, before the event was known to any but those on the scene. That day Narcissus Luttrell, the great chronicler of the state affairs of the era, recorded that there had been ‘no news of the Turkey fleet, which encourages us to think they are safe’. Prices remained at ten per

cent until at least the end of the week, and definitive news of the misadventure did not reach London for several more days.

Despite the high rates – even twenty per cent was much more than the peacetime norm – at least nineteen underwriters were unable to meet all of their commitments. Then, as now, each underwriter assumed risk with several liability. The assets of some were insufficient to meet their shares of the claims. Fourteen petitioned for state relief. A parliamentary scheme for the beleaguered merchant-insurers was read to the Commons in December 1693, and

attracted significant debate, including the publication of a pamphlet. Fear of a systemic collapse appears to have been genuine: the pamphlet stated that the ‘Practice and Custom of Assurance in the Kingdom is both Antient and Creditable’, and would be damaged if underwriters were allowed to fail.

On 22 February the name of merchant-insurer Daniel Foe was inserted into the Bill, and five days later it passed its third

reading. However, it was defeated in the Lords, for unknown reasons. Luttrell recorded, with characteristic terseness that ‘The Lords have flung out the bill for merchants insurers.’

Despite the failures, the London market endured. New men with new money soon came in to replace the ones who, like Defoe, had failed in the face of disastrous losses. Some, like Defoe, went on to succeed elsewhere. John Walter was a coal trader who, as a merchant-insurer, had shared risk by underwriting colliers at old Lloyd’s since the 1770s. He joined New Lloyd’s in 1781, and dangerously extended his underwriting. Almost immediately he was, in his own words, ‘weighed down, in common with about half of those who were engaged in the protection of property, by the host of foes this nation had to combat in the American War.’ Walter was forced from his home, sold his library, and managed to clear his debt only in 1790. Like Defoe before him, Walter changed his career (if not his name). In 1785 he launched the Daily Universal Register, a newspaper which, in 1789, he renamed The Times.

Another underwriter-cum-journalist was Walter Bagehot. Little is known of his underwriting success, although he wrote little about marine insurance. But like these individuals, the London marine insurance market was resilient. It frequently overcame obstacles, such as a fearsome attack on its reputation in the mid eighteenth century, just as it was getting established.

Over the course of that century, a taste for gambling had overtaken many of the merchants of London. One convenient way to wager was under insurance policies. Lloyd’s began to gain a reputation as a place where wager policies were rife. In 1768, the London Chronicle reported that the introduction and amazing progress of illicit gaming at Lloyd’s coffee-house is, among others, a powerful and very melancholy proof of the degeneracy of the times... [and has] met with so much encouragement from many of the principal Under-writers, who are, in every other respect, useful members of society... gaming in any degree is perverting the original and useful design of that coffee-house.

Specific wagers citied in the Chronicle include bets upon the election, death, and even execution of named individuals, on the declaration of war with France or Spain, and on the dissolution of parliament. The unnamed journalist declared these insurances were ‘underwrote, chiefly by Scotsmen, at the above Coffee-house’.

Lloyd’s reputation was at a nadir. The following year a small group of underwriters broke away, and established a new venue – called New Lloyd’s – to do business without wager policies. At a meeting of the subscribers held on 4 March 1774, they agreed that: Shameful practices which have been introduced of late years [to the] Business of Underwriting such as making Speculative Insurance on the Lives of Persons and on Government Securities – In the first Instance it is endangering the lives of the Persons so insured, from the Idea of being Selected from Society for that inhuman purpose, which is being Virtually an Accessory in a Species of Slow Murder – In the Second Instance of Speculative Insurance on the Stocks, it is Notorious they are Calculated for the purpose of Stock Jobbing and lend to weaken the Public Credit – It is therefore hoped that the Insurers general will refuse Subscribing such Policies and that they will shew a proper Resentment against any Policy Broker who shall hereafter tender such Policy to them.

The next day Lloyd’s moved to Gresham’s Royal Exchange, the former home of the Office of Assurances.

It occurs to me now that I have skated rather quickly over the story of Lloyd’s. It must begin with Edward Lloyd himself, who seems to have been a rather energetic entrepreneur. Not much is known about him, to be honest, considering he was so prolific. We do know he operated a coffee-house in Great Tower Street by at least the end of 1688, or 1689 according to modern dating. By 1692, to appeal to his customers involved in trade, he had launched the first version of his eponymous list, with the slightly awkward title Ships Arrived at, and Departed from several Ports of England, as I have Account of them in London, with a sub-section called An Account of what English Shipping, and Foreign Ships for England, I hear of in Foreign ports. The earliest extant copy of the publication yet discovered is number 257, dated 22 December 1696. From this we can calculate that the newspaper had appeared, at latest, by January 1692. At about that time, Lloyd had moved his business to the corner of Lombard Street and Abchurch Lane, at the heart of London’s mercantile district.

Information was of keen importance to ocean-going merchants. In these days of geo-positioning systems, cellular phones, and 4G connections it is hard to imagine an era when you could send away a vessel, carrying your fortune, and learn of its fate months or even years later in a newspaper, but this was the norm. For example, in 1759 the Glasgow tobacco merchants Buchanan & Simson, reported that ‘We find by this days Lloyds List that the [vessel] Maxwell foundered at Sea. As we have insurance made at Philadelphia, we desire you may by first Paquet to New York, send to Mr George Maxwell Merchant in Patuxent, Maryland a proper certificate of the ship being lost, that our insurance may be received’.

It should be noted that inhe late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries Lloyd’s was not yet the important centre of underwriting which it was to become. Two reports of great significance to our understanding of marine insurance were published in 1720 and 1824 respectively. Each presents the details of separate parliamentary enquiries into the marine market.

The first makes no mention of Lloyd’s; the second is full of it. Each contains the testimony of one of the market’s great men. The first that of John Barnard MP, a merchant underwriter in the wine trade, who went on to be an MP for the City and, according to one commentator of the day, a thorn in the side of Walpole himself. The second gives us the words of John Julius Angerstein, the man who returned the centre of underwriting in London to the Royal Exchange, whose art collection formed the nucleus of what was to become the National Gallery, and, less famously, with the Barings (first Sir Francis, then Alexander), raised millions for the government through loans to aid in the Napoleonic Wars. I have identified the records of this activity in an unspectacular ledger in the London Metropolitan archive.

Despite the distance of a century between them, these parliamentary reports show a London insurance market which was much bigger in the early eighteenth century than it was in the early seventeenth, but this is in line with the growth of British trade. In other respects, they show a market that operated in much the same way as it had since the late sixteenth century. Indeed, based on what I can glean from scattered Italian sources, it differed little from the Mediterranean market of the late fourteenth. It didn’t change much because it worked.

The law governing insurance – the Law Merchant – was wonderfully flexible, so insurance remained relevant and useful to its users. When events got ahead of practice, as in the Smyrna disaster of 1693, the market regrouped and resurged. People sometimes tried to defraud the insurers, but additions to the system, such as Candeler’s Office of Assurances, helped to minimise the problem, as did the improved information-sharing driven forward by Edward Lloyd and his successors. London marine insurance practice spread around the world on the ships of the British Empire, and London underwriters, like Gresham and Defoe before them, covered them every league of the way.

© Dr A. B. Leonard, Centre for Financial History, 13 March 2014

This event was on Thu, 13 Mar 2014

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham College plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login