Living with Mental Health

Share

- Details

- Text

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

There is a rising number of people of all ages with mental health illnesses globally, that has been accompanied by a greater willingness to talk about it in many places. What are the most common disorders and the best treatment options, including non-medical treatment and lifestyle modifications?

The lecture will conclude by looking at global mental health myths, for example in several cultures individuals with problems are considered to be holding a negative spirit inside them.

Download Text

Living With Mental Health

Professor Monica Lakhanpaul

6th February 2023

Mental health is a global problem, with 1 in 8 people globally experiencing mental health problems in their lifetime [1]. In 2019, estimated 4.9% of the UK population has an anxiety disorder, 4.5% suffered Depression and another 7.5% with other conditions [2]. The pandemic has had a further negative impact on the prevalence of poor mental health, with an estimated 27.6% increase in global cases of major depressive disorder and a 25.6% increase in cases of anxiety disorders [3]. Like physical health, everyone has to look after their mental health. However, some people can have chronic mental health conditions/illnesses that can affect their mood, thinking and behaviour. Common disorders include anxiety, depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, eating disorders and obsessive-compulsive disorders. In addition to the psychological impacts, these conditions can also have debilitating physical symptoms, including headaches, fatigue, nausea and trouble breathing.

“The hardest thing about having a mental health problem is people not realising there is something wrong with you, and that you can be really ill even if you look absolutely fine”

Woman, Young Adult, Eating disorder and Anxiety [4]

There are many factors that influence mental health. The biopsychosocial model categorises these on a biological, psychological and sociological level. Biologically, mental health can be affected by genetics, developmental deficits, and chemical imbalances. If a close relative has a mental health disorder, you are more likely to develop one too [5, 6]Although genetics predispose us to mental health conditions, our experiences can activate certain genes that would have otherwise remained dormant (epigenetics).

As so much of a child’s brain development happens at a young age, negative experiences in childhood can have lifelong physical and psychological consequences. These potentially traumatic events are called Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and can be grouped into three categories: Abuse (e.g. physical, emotional, sexual), Neglect (physical and emotional) and Household Dysfunction [7]. Adults experiencing at least four ACEs are at increased risk of all health outcomes and chronic childhood stress has also been shown to be associated with brain structural and functional abnormalities [7-9]. This means that preventing ACEs could have huge benefits to public health, the CDC projecting it could reduce depression by up to 44% [10].

The role of psychological and social factors in mental health mean that social inequalities also play a factor in developing mental health conditions. Living in a deprived area increases the risk of exposure to ACEs and creates financial stress. It has been shown that the worst off 20% of children are four times more likely to have a severe mental health condition [11], and that low-income households also had higher rates of mental health problems during the pandemic [12]. The LGBTQ+ community is also at greater risk of mental health problems. Stonewall released a report in 2018 that in showed that in the previous year 52% LGBT people experienced depression and 46% of trans people and 31% of LGB were suicidal [13]. Ethnic minorities are also at risk, with black women being more likely to experience anxiety and depression, black men more likely to be detained by the Mental Health Act, and having worse treatment outcomes [14-16].

However, although these factors influence the risk of mental health problems, they do not guarantee them, and the risk/impact can be mitigated by looking after their wellbeing and seeking help when needed. If someone is struggling with poor mental health, there are several ways that they can support their wellbeing.

Seeking a diagnosis is the first step to establishing what help is needed and building a treatment plan. Speaking to a GP is usually the first step towards referral to other services. NICE guidelines suggest doctors consider multiple ways of supporting patients struggling with their mental health[17]. If they believe the patient needs it, they may suggest medication. There are three main categories of psychiatric medication: antidepressants, anxiolytics, and antipsychotics. Their role is to manage the levels of serotonin, dopamine, and/or noradrenaline in your brain. Some people find taking medication beneficial in helping them manage their symptoms. However, they can have mild-severe side effects and sometimes it can take time to find the right medication. Psychotherapy is recommended alongside medication or as an alternative. It is the use of talking and interaction in the treatment of mental health. One of the most common tools is cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), a technique that focuses on understanding and identifying the patient’s feelings, challenging and reframing negative thoughts, and developing coping strategies for daily life[18].

Lifestyle modifications are also recommended to support mental health. Getting enough sleep, physical activity, a balanced diet, and spending time in nature have all been shown to improve mood and wellbeing[19]. Practices such as mindfulness are being taught in schools and workplaces as a method of managing emotions. It is a form of meditation that encourages focusing on the present moment, while acknowledging feelings, thoughts, and bodily sensations without judgement. This can be done in a formal way or simply while on a walk or sitting at home. It has benefits on anxiety, depression, stress, and overall wellbeing [20].

Engaging in creative activities can also benefit mental health and wellbeing. Older adults in England who regularly participate in cultural have nearly half the risk of developing depression than those who do not [21]. It is also linked to higher levels of wellbeing, reduced loneliness, and lower anti-social behaviour and risk taking. Listening to music during pregnancy and singing can even be used to treat post-natal depression [21]. The evidence that is mounting for the benefits of non-medical interventions has led to the NHS to developing a “social prescribing” initiative, which aims to connect people to community activities, groups, and services to meet the practical, social, and emotional needs [22].

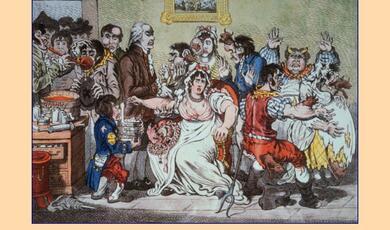

However, there are barriers that people face to accessing these treatments. Facing stigma can prevent people from asking for help, reduce self-esteem, continuing with treatment, and even worsen the condition[23]. This is a global problem and is often rooted in negative stereotypes or myths. Understanding these beliefs can help to understand the root of stigma so that approaches to reducing it can be tailored. For example, some Pentecostal Christians and Islamic groups believe the mental health problems are a result demonic or Jinn possession, with exorcism being the only way to “cure” the ailment [24, 25]. It is also common in communities across the world to believe the sufferer is cursed, with multiple rituals required as treatment from shamans and witch doctors. However, stigma exists in communities who believe in biological causes too. Mental health stigma particularly affects men, with many being unwilling or embarrassed to talk about their health [26]. 40% of men polled said that it would take having suicidal thoughts to consider seeking treatment. This is unsurprising, as men consistently have higher suicide rates across cultures worldwide [27], being almost three times as likely to commit suicide than women [28].

Even when having the courage to seek treatment, care is not always easy to access. 23% of patients surveyed waited more than 12 weeks to start treatment, with 12% waiting for more than 6 months [29].

“I had to wait six to seven months to be referred to a community team. The only other way to get help was to present to A&E, which was a traumatic experience ... No one should have to go through that" Woman, 45, Addiction and Depression[29]

Long waiting times can be tough for the patients and their families, and lead to worse outcomes [30]. These barriers can mean that families often have to support their loved ones alone. It is key that they listen to someone struggling with their mental health, ask them what support they need, and do not minimise their feelings. If they can, they should work together to establish a plan on how to move forward, whether it be through professional care or through other lifestyle changes [31].

The most important thing is to not treat people differently when finding out they have had problems with their mental health. It is something that can happen to anyone and at any point in life and is not a sign of weakness or a moral failing. Stigma needs to be fought and funding needs to be invested into mental health services and community projects to ensure that society can optimally look after the mental wellness of its people.

© Professor Lakhanpaul 2023

References and Further Reading

1. Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation, Global Health Data Exchange. 2019.

2. Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network, Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 Results. 2021, Institution of Health Metrics and Evaluation.

3. Santomauro, D.F., et al., Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet, 2021. 398(10312): p. 1700-1712.

4. Mind, Mental Health: In our own words. 2014.

5. The Centre for Genetics Education. Mental illness and inherited predisposition schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. 2012 [cited 2022; Available from: www.genetics.edu.au/publicationsandresources/facts sheets/factsheet59mentalillnessdisorders/view.

6. Telman, L., et al., What are the odds of anxiety disorders running in families? A family study of anxiety disorders in mothers, fathers and siblings of children with anxiety disorders. Europe and Child Adolescent Psychiatry, 2018(27): p. 615-24.

7. Felitti, V.J.M.D., et al., Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 1998. 14(4): p. 245-258.

8. Jedd, K., et al., Long-term consequences of childhood maltreatment: Altered amygdala functional connectivity. Development and Psychopathology, 2015. 27(4pt2): p. 1577-1589.

9. Frodl, T. and V. O'Keane, How does the brain deal with cumulative stress? A review with focus on developmental stress, HPA axis function and hippocampal structure in humans. Neurobiology of Disease, 2013. 52: p. 24-37.

10. Centre for Disease Control. Adverse Childhood Experiences. 2019; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/aces/index.html.

11. Gutman, L., et al., Children of the new century: mental health findings from the Millennium Cohort Study. 2015.

12. Fancourt, D., et al., COVID-19 Social Study: Results Release 42. 2022.

13. Bachmann, C.L. and B. Gooch, LGBT in Britain: Health Report. 2018.

14. Cabinet Office, Race Disparity Audit Summary Findings from the Ethnicity Facts and Figures website. 2018.

15. UK Government. Detentions under the Mental Health Act/Main Facts and Figures. 2021; Available from: www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/health/mental-health/detentions-under-the-mental-health-act/latest#main-facts-and-figures.

16. Mental Health Foundation. Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) communities. 2021; Available from: www.mentalhealth.org.uk/a-to-z/b/black-asian-and-minority-ethnic-bame-communities.

17. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Depression in Adults: Treatment and Management. 2022.

18. NHS. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy. 2022; Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/talking-therapies-medicine-treatments/talking-therapies-and-counselling/cognitive-behavioural-therapy-cbt/overview/.

19. Mental Health Foundation, Our Best Mental Health Tips. 2022.

20. Farb, N.A., et al., Minding one's emotions: mindfulness training alters the neural expression of sadness. Emotion, 2010. 10(1): p. 25-33.

21. Fancourt, D. and A. Bradbury Investing in the Arts can improve public health. 2022.

22. NHS, Social prescribing and community-based support: Summary Guide. 2020.

23. Yanos, P.T., et al., The impact of illness identity on recovery from severe mental illness: A review of the evidence. Psychiatry Research, 2020. 288: p. 112950.

24. Subu, M.A., et al., Traditional, religious, and cultural perspectives on mental illness: a qualitative study on causal beliefs and treatment use. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being, 2022. 17(1): p. 2123090.

25. Mercer, J., Deliverance, demonic possession, and mental illness: some considerations for mental health professionals. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 2013. 16(6): p. 595-611.

26. Priory Group Men's Mental Health. 2019.

27. OECD Suicide rates in selected countries as of 2019, by gender (per 100,000 population). Statista, 2022.

28. Office of National Statistics, Suicides in England and Wales: 2021 registrations. 2022.

29. Royal College of Psychiatrists. Hidden waits force more than three quarters of mental health patients to seek help from emergency services. 2022; Available from: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/news-and-features/latest-news/detail/2022/10/10/hidden-waits-force-more-than-three-quarters-of-mental-health-patients-to-seek-help-from-emergency-services.

30. Reichert, A. and R. Jacobs, The impact of waiting time on patient outcomes: Evidence from early intervention in psychosis services in England. Health Economics, 2018. 27(11): p. 1772-1787.

31. Mental Health Foundation. How to support someone with a mental health problem. 2022; Available from: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/explore-mental-health/articles/how-support-someone-mental-health-problem.

References and Further Reading

1. Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation, Global Health Data Exchange. 2019.

2. Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network, Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 Results. 2021, Institution of Health Metrics and Evaluation.

3. Santomauro, D.F., et al., Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet, 2021. 398(10312): p. 1700-1712.

4. Mind, Mental Health: In our own words. 2014.

5. The Centre for Genetics Education. Mental illness and inherited predisposition schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. 2012 [cited 2022; Available from: www.genetics.edu.au/publicationsandresources/facts sheets/factsheet59mentalillnessdisorders/view.

6. Telman, L., et al., What are the odds of anxiety disorders running in families? A family study of anxiety disorders in mothers, fathers and siblings of children with anxiety disorders. Europe and Child Adolescent Psychiatry, 2018(27): p. 615-24.

7. Felitti, V.J.M.D., et al., Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 1998. 14(4): p. 245-258.

8. Jedd, K., et al., Long-term consequences of childhood maltreatment: Altered amygdala functional connectivity. Development and Psychopathology, 2015. 27(4pt2): p. 1577-1589.

9. Frodl, T. and V. O'Keane, How does the brain deal with cumulative stress? A review with focus on developmental stress, HPA axis function and hippocampal structure in humans. Neurobiology of Disease, 2013. 52: p. 24-37.

10. Centre for Disease Control. Adverse Childhood Experiences. 2019; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/aces/index.html.

11. Gutman, L., et al., Children of the new century: mental health findings from the Millennium Cohort Study. 2015.

12. Fancourt, D., et al., COVID-19 Social Study: Results Release 42. 2022.

13. Bachmann, C.L. and B. Gooch, LGBT in Britain: Health Report. 2018.

14. Cabinet Office, Race Disparity Audit Summary Findings from the Ethnicity Facts and Figures website. 2018.

15. UK Government. Detentions under the Mental Health Act/Main Facts and Figures. 2021; Available from: www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/health/mental-health/detentions-under-the-mental-health-act/latest#main-facts-and-figures.

16. Mental Health Foundation. Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) communities. 2021; Available from: www.mentalhealth.org.uk/a-to-z/b/black-asian-and-minority-ethnic-bame-communities.

17. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Depression in Adults: Treatment and Management. 2022.

18. NHS. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy. 2022; Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/talking-therapies-medicine-treatments/talking-therapies-and-counselling/cognitive-behavioural-therapy-cbt/overview/.

19. Mental Health Foundation, Our Best Mental Health Tips. 2022.

20. Farb, N.A., et al., Minding one's emotions: mindfulness training alters the neural expression of sadness. Emotion, 2010. 10(1): p. 25-33.

21. Fancourt, D. and A. Bradbury Investing in the Arts can improve public health. 2022.

22. NHS, Social prescribing and community-based support: Summary Guide. 2020.

23. Yanos, P.T., et al., The impact of illness identity on recovery from severe mental illness: A review of the evidence. Psychiatry Research, 2020. 288: p. 112950.

24. Subu, M.A., et al., Traditional, religious, and cultural perspectives on mental illness: a qualitative study on causal beliefs and treatment use. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being, 2022. 17(1): p. 2123090.

25. Mercer, J., Deliverance, demonic possession, and mental illness: some considerations for mental health professionals. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 2013. 16(6): p. 595-611.

26. Priory Group Men's Mental Health. 2019.

27. OECD Suicide rates in selected countries as of 2019, by gender (per 100,000 population). Statista, 2022.

28. Office of National Statistics, Suicides in England and Wales: 2021 registrations. 2022.

29. Royal College of Psychiatrists. Hidden waits force more than three quarters of mental health patients to seek help from emergency services. 2022; Available from: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/news-and-features/latest-news/detail/2022/10/10/hidden-waits-force-more-than-three-quarters-of-mental-health-patients-to-seek-help-from-emergency-services.

30. Reichert, A. and R. Jacobs, The impact of waiting time on patient outcomes: Evidence from early intervention in psychosis services in England. Health Economics, 2018. 27(11): p. 1772-1787.

31. Mental Health Foundation. How to support someone with a mental health problem. 2022; Available from: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/explore-mental-health/articles/how-support-someone-mental-health-problem.

Part of:

This event was on Mon, 06 Feb 2023

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham College plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login