Predictable Surprises

Share

- Details

- Text

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

Many mistakes in business look obvious in hindsight. Yet they usually take us and our organisations by surprise. What explains this paradox?

This lecture explores why predictable surprises happen and what individuals and organisations can do to protect themselves from unpleasant surprises. We know a lot about how bad decisions happen.

But how we can we make good decisions amidst ambiguity, when everything is uncertain - even uncertainty itself?

Download Text

4 December 2014

Predictable Surprises

Professor Helga Drummond

Almost any decision involving uncertainty risks failure. Failure often strikes like a bolt from the blue. Yet looking back, it seems blindingly obvious. For instance, banks that gave mortgages to people who simply could not afford to re-pay when teaser rates of interest ended. But why didn’t they see it?

Most disasters look obvious in hindsight. The Far East was ablaze with rumours predicting Barings’ imminent collapse in 1995. Why did the bank not investigate until it was too late? Think of the more recent Nimrod disaster. The plane caught fire and exploded in mid-air over Afghanistan in 2006, killing all fourteen crew. The fire was traced back to a design flaw that had lain dormant since the plane entered service in 1969. Yet less than two years earlier, the fatally flawed aircraft had passed a Safety Case examination.

Strictly speaking, if something is predictable it can hardly come as a surprise. Yet that is exactly what happens. Barings’ sudden collapse was the last thing directors expected – even though there were at least five other signs of malfeasance. US security forces knew “something bad was up” but could not make the imaginative leap to see what. Nimrod was pronounced “acceptably safe to fly”.

This lecture explores two main reasons for predictable surprises. One concerns psychological traps. The other relates to paradox and contradiction and why apparently sensible decisions can produce mayhem. I also explore what we can do to protect ourselves from costly mistakes.

PSYCHOLOGICAL TRAPS

The Over-Confidence Trap

Imagine you are buying a lottery ticket. What do you prefer:

- take a ticket from the shop keeper; or,

- choose your own?

You can assume the shop keeper is honest.

Logically it makes no difference to the probability of winning which option you select. But you may decide you would rather choose your own ticket – why?

Psychologists believe that we are habitually over-confident. That we tend to over-estimate our capabilities and see ourselves as superior to other people. (In this view incidentally, depression is not seeing things as worse than they are but as they are. [1]We also find it almost impossible to believe that we might be wrong. We even think we can control chance. For instance, research into gambling behaviour has shown that players tend to shake softly if they need a low number.[2] Whereas if players need a high number – they give the dice a good rattle!

Psychologists call it the illusion of control. Think of the daily “to do” list. Most people set themselves far more than they can possibly accomplish in a day. And, next day, undaunted they repeat the mistake!

The point is, feeling in control makes us feel more confident. Confidence encourages risk-taking. The illusion of control is thought to be heightened where a game involves skill as well as luck. For instance, research into gambling behaviour shows that if players are allowed to deal the cards, they tend to bet more. That is why “fruit machines” incorporate “nudge” and “hold” buttons. The trick is making players feel they can influence outcomes by exercising skill and judgement.

The same goes for our daily lives and in business. Success usually reflects a mixture of competence and luck. But what was due to competence and what was merely fortuitous?

The answer is seldom in doubt. We typically attribute success to our innate competence and failure as bad luck or other peoples’ mistakes and shortcomings. Look at company reports and you will see this pattern. Directors are happy to claim credit for success (and they probably believe credit is their due) whilst bad results are invariably blamed on factors outside directors’ control like freak weather conditions and weak markets. That may also be one reason why investors often hang on to non-performing shares and sell the good ones. They simply cannot believe their investment strategy was wrong. Such self-serving beliefs protect our egos. But since we are never at fault we never learn from our mistakes.

Nothing Succeeds Like Success?

Nothing succeeds like success says the proverb. True: to a point. But only to a point! Being on a roll can become a liability. This is because repeated success confirms our competence. It tells us we cannot fail. So we can end up taking bigger and bigger risks – often without realising it. For instance, research has shown that players experiencing early wins in games of chance tend to raise their bets. There is no logical reason to do so because the game is pure chance. But success can make players feel omnipotent.

It is the same in other walks of life. Having succeeded in the past we expect to succeed in the future. Porsche were the most profitable car makers in the world – until they tried to take on VW – a company eighty times their size in an audacious gamble that cost Porsche their independence. Remember Tesco’s meteoric rise. But now look at them! A large part of Tesco’s woes stem from a disastrous foray into the US with their “Fresh and Easy” chain. As the media dubbed it, “Fresh But Not So Easy”. Industry experience showed that foreign retailers usually need twenty years to gain a foothold in the US. Tesco’s big mistake, was they thought they could do it in two.

Repeated success can also make us careless. For instance, we stop doing the things that made us successful in the first place. Or, we may just do one of the things that made us successful before and forget everything else.

SENSE-MAKING TRAPS

Over-confidence may be a ubiquitous trap. But it is not the only one we can fall into. To be more precise, before we can make a decision we have to make sense of things. That means we have to simplify. The trouble is, when we simplify we may pay too much attention to some information and not enough attention to other information.

All That Glitters: Vividness Traps

Vividness refers to our innate tendency to pay more attention to dramatic images at the expense of considering facts and figures. For instance, we tend to notice bright colours. So as we scan a crowd we are more likely to notice the people who are wearing red, orange, yellow as distinct from dark blues, black and shades of grey even though the latter make up 90% of the crowd. Now if you happen to be the buyer for fashion house and conclude that bright colours are in vogue and stock-up accordingly – that’s an expensive mistake.

To be more precise, events that are portrayed vividly seem closer and more probable than they really are. One reason why we worry more about being killed in a plane crash than a car crash is because car crashes are seldom reported whereas a plane crash makes headline news. In fact, you are much more likely to die in a car crash.

This is why fairground owners pile coins tantalisingly high and close to the edge. It looks as if just one more coin is all that is needed to tip the whole pile of coins into the tray below with a satisfying clatter. In fact, as you know, most of the money disappears down the back of the machine. Even so, the heap of coins teetering near the edge keeps us playing!

“Wow! Grab it!

A particularly interesting form of vividness is the dazzling opportunity that seems just too good to lose. The reaction becomes, “Wow! Grab it” But it may be a trap.

For instance, a small brewery intended to expand production cautiously and moderately on site in order to meet the growing demand for real ale.[3] Most unexpectedly, the directors were offered the chance to buy a redundant brewery cheaply. It seemed like a fantastic opportunity that would enable an EIGHT FOLD expansion! So the directors went ahead even though one non-executive director resigned over the decision.

It was a disaster. Quite apart from all the technical problems – the directors suddenly had eight times as much beer to sell. To make matters worse, they discovered margins on large scale production were much thinner than for a small scale product. They quickly went bankrupt. The mistake was falling into a vividness trap. That is, the directors let them-selves to be seduced by a glittering opportunity – that was not all it seemed to be.

Confirmation Traps

The other mistake was ignoring the doubts of an experienced non-executive director. Perhaps the directors of the brewery thought the non-executive director was too cautious, too staid, too “stick in the mud”. Or simply telling them what they didn’t want to hear …

Psychologists call it the confirmation trap. That is, our innate tendency as human beings to pay more attention to information that seems to confirm our pre-conceived views whilst down-playing or even ignoring contradictory information.

Like all traps, it happens unconsciously. That means decision-makers may be genuinely convinced that things are not as bad as they seem to be. They may really believe that problems are temporary, that success is close and difficulties are exaggerated and so forth when the reverse is plainly true! For example, RBS came close to nemesis following the ill-advised acquisition of ABN-AMRO. RBS dismissed repeated warnings from analysts that ABN-AMRO was over-valued. RBS thought they knew best and forgot that pride comes before a fall.

The Trap of Experience

Experience can become a trap if we think we have seen it all before. To be more precise, if it leads us to see the similarities between past and present cases, but not the differences. For example, doctors know what to look for when diagnosing flu and heavy colds. But some serious illnesses present similar symptoms earlier on. If doctors are not alive to subtle differences they may miss the onset of a more serious illness.

That may also partly explain the mistake made by the directors of the brewery I mentioned earlier. That is, they probably saw the similarities between the two operations - both brewed beer - but failed to recognize that was where the comparison ended. In fact, running a big brewery was a profoundly different challenge from running a small one.

Anchoring Traps

At the time of writing, the new iPhone 6 phablet costs about £620. Co-incidentally, the latest Samsung Note is even more expensive - £650. Logically you might expect Samsung to under-cut Apple. But what they may be trying to do is to anchor the phone’s value in the minds of consumers – reassuringly expensive.

Anchoring refers to our innate tendency to pay attention to information that may not actually be irrelevant. That is why clothes’ retailers mark high prices on garments that they then drastically reduce. The trick is, the high price remains anchored in our minds – making us feel we got a good deal – when it is complete illusion!

The same happens in business. One reason why big projects end up costing a lot more than anyone imagined is that planners start with estimates that are far too low. Although those estimates may get revised as they move up the hierarchy, those revisions are rarely drastic enough because they tend to be rooted (anchored) in the originals.

Anchoring also explains why first impressions are so important. If you made a bad impression, although you may subsequently work to change it, it is likely to be an uphill struggle. This is because everything is judged against that first impression.

Expectation Traps

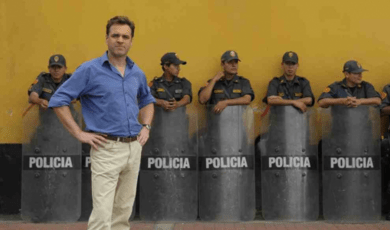

At first glance, you may have thought that theslide says “police notice” because of the adjoining image of the police officer. On other words, what you expected to see. They say perception is reality. But expectations can also seem real.

In 1977, some of you may remember, two jumbo jets collided on the runway at Tenerife airport killing over 500 people in the world’s worst aviation disaster. There were no survivors. To this day the crash remains a mystery. Why did the KLM pilot attempt to take off without authority straight into the path of another plane?[4]

Poor visibility was one factor. In addition, flights were running late. The KLM crew were running out of flying hours and anxious to get away. It is thought that when the control tower finally issued the long-awaited instruction, “Okay standby to take-off” (or similar) the stressed crew may have heard what they expected (and wanted) to hear, namely “Okay take-off”. Moreover, when the KLM pilot radioed “OK we are taking off” (or similar) staff in the control tower may have heard what they expected to hear, “OK we are at take-off position.”

The lesson is that expectations can dictate what we see and here. Not only that, but once we formulate an expectation or an explanation for something, powerful blind spots can develop for contrary information. For instance, a group of firefighters in the US were sent to deal with a forest fire at Mann Gulch. The crew were briefed to expect a so called “ten o’clock fire” that is, one that would under control by ten o’clock next morning. In fact, the fire was much more serious. But having been briefed to expect a ten o’clock fire, as the helicopter flew over the forest, fire fighters rationalised all the danger signs to fit the explanation of a ten o’clock fire. So when they came to fight the blaze the crew were hopelessly unprepared and most of them were killed.

In a sense expectations are reality. For instance, one of the big questions posed by the media was whether Barings secretly knew about Nick Leeson’s unauthorised trading. There is no evidence to suggest they did. In fact, it was probably the other way round. Barings were taken completely by surprise – even though directors had heard rumours about massive exposure to a mystery client and even though latterly they knew that reputable investment houses were warning clients to steer clear of Barings.

I think what happened was Barings saw a busy trader trying to do two jobs. That is, trading and then spending half the night doing the paperwork - so mistakes like £50 million going walkabout; chronic reconciliation problems of over £100 million, Leeson not explaining how millions of pounds in collateral were being used – was only to be expected. It was only when Leeson mysteriously disappeared that alarm bells began to ring. Here was something that did not fit expectations. By then the bank was doomed.

Expectations may also explain why society has been slow to recognise abuse of children and vulnerable adults. Indeed, in extreme situations people tend to exercise self-censorship. That if we see or hear something that is so outlandish it seems incredible, we are likely to tell ourselves, “It can’t be. Therefore it isn’t.”[5] Incidentally expectations may be one reason why Jimmy Saville was never properly investigated over alleged sexual offences. Whenever a complaint was made the response was “Jim gets lots of these.” It is called hiding in plain sight.

PARADOX AND CONTRADICTION

So far I have talked about psychological traps. Let’s now look at some of the dynamics of paradox and contradiction and why apparently sensible decisions can have unwanted and unexpected consequences.

Consistency Traps

Why “More” of a Good Thing is Not Always Better

Why Virtuous Circles Can Turn Vicious

It is human to want more and more of a good thing. But nothing goes on getting better and better indefinitely. Otherwise, grass and trees would touch the sky instead of regressing to the mean.

For instance, medieval monasteries practised industrial efficiency to a fine degree. The monk’s aim was simple, streamline work in order to maximise time for prayer. But the monks became too successful for their own good. Thanks to their super-efficiency the monks also became super-wealthy. Wealth corrupted monastic orders. Piety gave way to gluttony and idleness and eventual downfall.

More recently, whatever happened to HTC? It is not that long since they seemed to come from nowhere to storm the smartphone market. But they are now trailing behind competitors. Did HTC’s much feted “magic labs” somehow become a liability?

The Paradox of Consequences

Imagine two people in a sailing boat: both frantically trying to steady an already steady boat. Sure enough they capsize the vessel. Moral: sometimes our unbridled efforts to prevent something precipitate the very situation we were trying so hard to prevent. For instance, if police officers, desperate to maintain law and order intervene forcefully amongst a crowd of noisy football supporters they may well precipitate the very riot they were there to stop. If they had just stood at a distance, keeping an eye on things, the danger would eventually have passed and they would not have destabilized the situation.

Another, related, reason for predictable surprises is that instead of abandoning an ineffectual course of action, we apply “more of the same” – only to make things worse. For instance, the medieval guilds were once extremely powerful. But unlike like the Mercers, many did not survive the advent of the industrial revolution. But it wasn’t the coming of the factory system that killed them so much as the guild’s reaction to it. The guilds stood implacably opposed. Logical but suicide! In the end, the captains of industry simply circumnavigated the guilds. They set up their new factories well away from areas where the guilds had strong influence. History might have been different if the guilds had worked with newly emerging industries instead of against them.

The Icarus Paradox

The fabled Icarus was equipped with a set of wax wings that enabled him to fly. Icarus soared on his new found freedom and flew closer and closer to the sun. His wax wings melted sending Icarus plunging to his death in the Aegean Sea. Moral: it may be the very things that make us successful that become our downfall if taken too far.

I emphasise that because Icarus died not because he flew: and not even because he flew near the sun. But because he flew too near. Similarly, in firms prudence can harden into penny pinching and/or refusal to take a risk that on economic grounds, a firm should take. Or, an innovative firm can go too far and start turning out gratuitous inventions. For example, products that may be renowned for say engineering excellence but have little commercial appeal. I mentioned HTC earlier. Their most recent smartphone offering was packed with sophisticated features. But few people bought it. Was that the problem? One explanation consistent with Icarus is that the so called “Magic Labs” were churning out smart electronics for which there was simply no market. Another possibility is that HTC focussed too much on invention and not enough on marketing and advertising.

GETTING DECISIONS MORE RIGHT THAN WRONG

Clearly there is plenty that can go wrong. How do we guard against the pitfalls? The main thing to remember is that these traps are systematic. Being aware of them means we can guard against them.

Get Real

Systematic means predictable. For example, we can be sure that we will never get through even half of the tasks on our “to do” list. The solution is to prioritise – first things first – that is deal with the crocodile that happens to be chewing the canoe. Worry about the ones upstream later.

Be Humble

If you push your luck, it will push back. Over-confidence means we usually put too high a value on ourselves. Many a contract (and many a lover) has been lost by playing too hard to get. If you don’t return a phone call promptly, a prospective client may well look elsewhere. By all means negotiate. But be mindful that no one is indispensable. Many a career has been ruined by holding out for too high a price and ill-advised ultimatums. Remember: pride comes before a fall – always, always.

Remember too that others are also likely to be over-confident. For instance, team members tend to regard one another as more of a hindrance than a help. They may scorn good ideas simply because they didn’t think of them. Similarly, research has shown that negotiators tend to over-estimate the likelihood that their final offers will be accepted. Litigants too go to court expecting to win – encouraged by overly confident lawyers.

The antidote lies in Quaker Advices, that is, when you are absolutely rock solid certain of something, just pause for a moment and think it possible you may be mistaken. If that seems like a monumental waste of time because nothing can possibly go wrong, that in itself is a warning sign.

Assumptions: Ass U Me (And Other Sobriquets)

Assumptions turn us into fools. Look carefully at what assumptions you are making – bearing in mind that we often make assumptions without realising it. For instance, every time we turn on the kitchen tap we expect water to flow. But it is an assumption. Then there was the party of pensioners from a village in Shropshire who went to Blackpool for their holidays. One day it rained. Seeing a “mystery tour” advertised, they decided to take it. And where did the bus take them? Right back to where they lived! Of course, it never occurred to them for one moment that this would happen. [6]

By the same token, Barings knew that Leeson’s positions were matched. That means every contract to buy was matched by an equal and opposite contract to sell. But what actually did they know? Most important how did they come to know it? In fact, everyone knew Leeson’s positions were matched simply because everyone else said so. So no one bothered to check. As we now know, Leeson’s positions were completely open leaving Barings’ exposed to catastrophic risk. If only someone had recognised that this seeming rock solid certainty was mere assumption, Barings might have been saved.

Keep Your Head

The cure for vividness traps is to keep focussed on facts and figures. And practicalities: an opportunity is only worth pursuing if you can deliver on it. Otherwise it is likely to become a liability. Shunning opportunity can be hard. From birth it is drummed into us that time and tide wait for no one; who dares wins, and the necessity of entering the raffle. But we also need to be to be bold in not daring. Success may indeed reflect the timely pursuit of opportunity. But sustained success may also owe something to the opportunities that we have the courage and self-discipline to reject. Pursuit of the unattainable costs us the possible. Who dares not sometimes wins in the end.

Look Again

If two things seem similar, look for differences. In any moderately complex decision, two situations are rarely identical. Consider too what may have changed between time period and another. There is no law that says the next “swan” won’t be a black one or a nasty shade of off-white.

Expect the Unexpected

Advising people to expect the unexpected is maybe a vacuous phrase. Even so, it pays to think about how you might be surprised. It is safest to imagine an expectation as something just waiting to be proved wrong. What tiny discordant note may you have overlooked or dismissed as inconsequential? What are you taking for granted? For instance, Porsche assumed that a critical byelaw would be repealed, allowing them to take VW over. In the end, legislators changed their mind. Porsche omitted to ask the “what if” question.

Predictable surprises are often failures of imagination. Before Harold Shipman was convicted, we did not imagine doctors as serial killers. It pays to remember Shakespeare’s words, that there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of.

Haul Anchor

Find out where the figures came. Ignore irrelevant information. Bear in mind too that other people are likely to be influenced by irrelevant anchors. For example, research has shown that surveyors are influenced by guide prices.

Perception may be reality but perceptions can be changed. Try small, well-timed gestures that contradict initial impressions. It also helps if those gestures and are likely to be appreciated by the other party. For example, send a hand written note.

A good ending can make up for a bad beginning. For instance, instead of escorting an important visitor to the lift, walk them back to their car. That may be the only thing they remember about the whole encounter!

Quit While Ahead

The most important thing in avoiding consistency traps is to remember that nothing goes on getting better and better indefinitely. The trick is to change direction sooner rather than later. By all means build on success – but if I can use the analogy, resist the temptation to keep adding another floor to the building.

But when is the best time to quit? I suggest “well before you want to”. To put it another way, imagine you meet someone attractive at a party. When is the best time to leave? The answer is not at a minute to twelve, or even five minutes to midnight, but about half past eleven. The same goes for selling investments or a business. Leave well before the wheel of fortune turns against you. Let someone else have the last ten percent. In the words of Joseph Kennedy, (father of the assassinated President), “Only a fool holds out for top dollar.”

Look For the “Problem Behind the Problem”

Sometimes it is not the problem itself that stands in the way so much as the assumptions we make about the problem. For example, a medieval castle was besieged – surrounded for weeks. Inside the garrison were growing desperate – in imminent danger of starvation. The captain then had an idea that seemed almost suicidal to his followers. He had their last ox slaughtered. Then he ordered the troops to stuff it with barley before tossing it contemptuously over the battlements. When the besiegers saw what had happened they lost heart and moved on. [7]

The captain succeeded by addressing the problem behind the problem. He recognized that the objective in war is not to fight the enemy but to destroy their will to fight. In other words, the captain stood back from the immediate problem and thought about things from the opponent’s point of view. Held up for weeks, enemy troops might be longing for home. Just one well timed gesture might be all that was needed to finally break their weakened morale. So it proved.

A more recent example concerns Scotland’s drinks laws. Before 1976, drunken behaviour was a major social problem in Scotland. It seemed odd because the pubs shut early. Indeed, the reaction was to shut them earlier still. But that only made things worse. The idea of opening them all day must have seemed like lunacy.

But as we now know, that move solved the problem. Because the problem behind the problem was that short opening hours meant fast drinking. Tightening licencing hours made only things worse. In contrast, “all day drinking” removed the pressure.

By the same token, the opening of Denver International Airport once looked as if it might be delayed almost interminably because the promised “state of the art” automated baggage systems couldn’t be made to work. In the end, an engineer built a scale model of the system and showed conclusively that it was never going to work. Now what?

Of course the over-riding objective was not to build a state of the art baggage system but to get the airport up and running. As the authorities finally recognised, that objective could be achieved by substituting a conventional semi-automated system that could be built using tried and tested technology. Moral: solve the right problem. Sometimes we end up looking for the solution in the wrong place - like the drunk searching for their car keys not where they dropped them but under the lamp-post because the light is good.

Change the Approach

Madness is repeating failing actions expecting different results. If something plainly isn’t working try changing the approach. For instance, if someone repeatedly fails to reply to e-mails, change the game: go and see them.

Think: How Might This Play Out?

Part of the art of avoiding predictable surprises is shining a mirror round corners. How is a prospective decision likely to play out? For all that has been said about the perils of uncertainty, some things are fairly certain. One question you can ask yourself is, if I do this, what will happen for sure? For instance, anyone who opens a business will discover that from day one money flows out in the form of rents, business rates, wages, stock and so forth. Where is that money going to come from? If the directors of the brewery had only stopped to think how events were likely to unfold, they might have secured new customers and stepped up production gradually instead of finding themselves awash with gallons of unwanted beer – a highly perishable product.

Leave Well Alone?

Some things are best left undone. Indeed, inaction can be the highest form of action. But not always! Inaction can pose dangers too. That leads me to the trailer for my next lecture, “The Psychology of Doing Nothing.” When to act and when not to? Thank you for listening. I look forward to seeing you there.

© Professor Helga Drummond, 2014

[1] Taylor, S. E. (1980) Positive Illusions, New York, Basic Books.

[2] For example, Langer, E. J. (1975) ‘The illusion of control,’ Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 975-986.

[3] Wilson, D. C., Hickson, D. J. Miller, S. (1996) ‘How organizations can over-balance: decision over-reach as a reason for failure,’ American Behavioral Scientist, 39, 995-1099.

[4] Weick, K. E., (1990) ‘The vulnerable system: an analysis of the Tenerife air disaster,’ Journal of Management, 16, 571-593.

[5] Weick, K. E. (1995) Sense Making in Organizations, Beverly Hills, Sage. This source includes reference to the Mann Gulch fire disaster.

[6] I am indebted to Jenny Wilbraham for this anecdote.

[7] Watzlawick, P., Weakland, J. H., & Fisch, R. (1974) Change: Principles of Problem Formation and Resolution,Norton, New York. Also alludes to the “steady boat” paradox.

This event was on Thu, 04 Dec 2014

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham College plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login