Respecting and Transcending Nature

Share

- Details

- Text

- Audio

- Downloads

- Extra Reading

One of the most distinctive characteristics of human beings is their capacity to alter their environments through technology. This raises important ethical and religious questions concerning the human engagement with nature, such as whether there are limits to what we can do with science (as in the genetic modification of crops). Yet there are deeper questions, about the way in which science can be used for destructive purposes.

The writing of J.R.R. Tolkien (1892-1973) show how his experience of the technology of warfare in the First World War had a lasting impact, causing him to reflect on how science could be used to destroy humanity, as much as to improve conditions. Tolkien's Lord of the Rings contrasts the purity and simplicity of those living close to nature with those who try to alter nature for their own ends. Reflections on scientific and religious frameworks enable us to respect nature on the one hand, while transcending its limits on the other.

Download Text

21 February 2017

Respecting and Transcending Nature:

J. R. R. Tolkien’s Concerns about Technology

Professor Alister McGrath

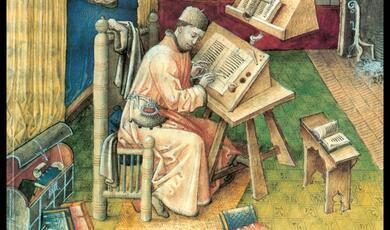

In this lecture, I want to reflect on the difficult yet important question of technology and the transformation of our world. I know that many of you will have already thought about this, and I hope that I will be able to provide some further grist for your intellectual mills. Although I will be interacting with several significant figures in this lecture, the most interesting of them is J. R. R. Tolkien, best known for his first book The Hobbit and his later epic The Lord of the Rings. Those of you who have read these will probably already have a good sense of the nature of Tolkien’s anxieties about technology, which are expressed in the plotlines and characterizations of these works. The Hobbits are an innocent people, who live close to the world of nature, and have no concern to dominate their neighbours or get involved in warfare. They want to grow crops in the fertile plains of Hobbiton, and so develop technologies appropriate to this modest task. But these are very limited technologies, designed to dig the ground, to harvest crops, and to prepare food. Technology is about the remaining close to nature, and enhancing human wellbeing.

Now let’s contrast this with Tolkien’s rather dark and menacing descriptions of the development of technology in the land or Mordor. In Tolkien’s Elvish Sindarin language, Mor-Dor means Dark or Black Land. This has led some to suggest that Tolkien may have based Mordor on England’s “Black Country” – an industrialized wasteland, where the processes of technology have turned a beautiful countryside into a barren scene of desolation. Some of you may have been to see the 2014 exhibition “The Making of Mordor” at Wolverhampton Art Gallery which explores the possible links between Tolkien’s fantasy fiction and the Black Country’s industrial past.

In her sassy autobiographical novel How to build a Girl (2014), partly set in Wolverhampton, the author Caitlin Moran portrays her father as reflecting in the early 1990s on the transformation of northern England from verdant rural landscapes to toxic industrial brownsites, using Tolkien’s novels to frame his concern about the degradation of the Black Country.[1]

Now we’ll come back to Tolkien in due course. But you can see the issue that he’s worried about. Technology can be used to heal and to destroy. The philosopher John Gray made a similar point in his Straw Dogs (2002), an iconoclastic book which caustically debunked bland humanist philosophies. For Gray, “humans cannot live without illusion” – such as a blind faith in progress, or the goodness of human nature.[2] Humanists may like to delude themselves that they have a rational view of the world; yet their core belief in moral progress is a “superstition”, which is arguably further from the truth about the human animal than any of the world’s religions. Progress in science and technology is subservient to selfish and corrupting human agendas, and does not inevitably lead to social and political progress. “Without the railways, telegraph and poison gas, there could have been no Holocaust.”[3] Now there is an element of overstatement here; yet there is also an element of truth. Weapons of mass destruction are human creations, based on the application of science to the advancement of nationalist or ideological ends. It’s no accident that Primo Levi, one of the few survivors of Auschwitz, spoke of “inhabiting the century in which science became warped”, creating a “gigantic death-dealing and corrupting machine.”[4]

The complexity of things began to dawn on me as I worked on synthetic routes for complex organic compounds. The leading authority on this subject was the Harvard scientist Louis Frederick Fieser (1899-1977), whose classic series Reagents for Organic Synthesis gave me lots of ideas for my own work. Fieser and his wife pioneered the artificial synthesis of a series of important naturally occurring compounds, including the steroid cortisone and Vitamin K, which was needed for blood coagulation.[5] The Fiesers’ brilliant synthetic procedures made medically important chemicals much cheaper and more widely available, with highly beneficial outcomes for patient care.

It was only later, however, as a graduate researcher in Oxford University’s Department of Biochemistry, that I learned that Louis Fieser had also been involved in another project during the Second World War. The U.S. Army urgently needed a chemical weapon suitable for eliminating troop concentrations in jungles and firebombing cities in the Pacific war theatre. Fieser and his team of chemists at Harvard won the contract to develop this weapon of mass destruction. They invented “napalm”, a petroleum gel that stuck to buildings and human bodies. Once ignited, it could not be removed or extinguished. Tests by the U.S. Army’s Chemical Warfare Service confirmed it was an ideal weapon for firebombing Japanese cities. Napalm proved to be a phenomenal military success, killing more Japanese civilians than the two atomic bomb blasts of 1945 combined.[6]

When I first learned about this, I found myself deeply conflicted about Fieser. How could someone who had pioneered ways of synthesizing chemicals that would extend human life and enhance its quality also create a chemical that was specifically designed to end life on an industrial scale, in a horrifically inhumane manner? The impact of napalm on Japanese soldiers and civilians was psychological, not merely physical, evoking a horror of being burned alive in a hideously painful manner.[7] My perception of Fieser changed, becoming darker and more unsettled, partly reflecting my difficulty in holding these aspects of his professional career together in my mind, and partly because this triggered off a more troubling question. What if this moral ambiguity in a leading scientist was also embedded within science itself?

How can we – indeed, should we – try to see the natural world as something special and wonderful, rather than something that we simply exploit for commercial gain through technology?How do we respond to the possibility of human technological enhancement – in other words, to the possibility that we might be able to extent our natural powers and lifetimes through technology? This important trend is often referred to as “transhumanism”.How can we – indeed, should we – check the tendency to use technology to develop tools of destruction, rather than enhancement?So let’s begin to look at the first of these questions. In a perceptive essay entitled “The Illusion of the Two Cultures”, the American evolutionary anthropologist Loren Eiseley argued that science and art – and, I would add, religion – are born of the same mind and are driven by the irresistible power of the human imagination.[8] Eiseley – sometime Professor of Anthropology and History of Science at the University of Pennsylvania. Eiseley expressed concern that the contemporary academy, through a relentless enforcement of disciplinary boundaries and its cult of “professionalism”, was draining a life-giving imaginative power from the sciences. Human beings had come to trust as real only those objective truths revealed by science and the artificial world which they themselves had constructed. The category of mystery was banished or declared to be redundant, meaning at most something that is not presently comprehended by science. But what if there was more to things than this?

Eiseley was critical of what we might call a detached, third-person approach to science, which treated nature as an impersonal object to be investigated – rather than as something to be respected, loved, and admired. There had to be a way of restoring this sense of wonder, and reconnecting with a sense of being part of something greater. Human beings have the potential for stereoscopic vision, in that they can discern meaning within the world, and not simply figure out how things work. One of Eiseley’s concerns was that technological progress was turning us into one-eyed creatures, capable only of envisioning a reduced world, in which things are defined in terms of their function. Today’s” secular disruption between the creative aspect of art and that of science” represents an unnecessary and reversible fracture, dependent for its imaginative plausibility on “the deliberate blunting of wonder.”[9]

In his best-known essay “The Star Thrower”,[10] Eiseley describes walking along a beach and encountering a boy throwing stranded starfish back into the ocean. Eiseley initially regarded this as pointless. “You can’t save them all, so why bother trying? Why does it matter, anyway?” The boy thought otherwise, as he picked up a stranded starfish. “It made a difference to that one”, he said, throwing it back into the sea.

As a scientist, Eiseley was perfectly aware that he should have no compassion for those starfish, as if they were reflective beings that cared whether they lived or died. Darwinian Theory held that evolutionary progress required death; so why interfere with this natural process? Yet as a human being, he found himself realizing that, as a scientist, he had missed something. “It was as though,” he writes, “at some point the supernatural had touched hesitantly, for an instant, upon the natural.”[11] The next day, Eiseley was on the same beach, throwing stranded starfish back into the ocean. It was, he mused, both an act of renunciation of his scientific heritage, and an embrace of a greater vision of things.

Classic forms of humanism, such as those which emerged in the Renaissance, emphasised the beauty and elegance of human nature, taking delight in the complexity of the human body and the range of human achievements. More recently, however, schools of thought have emerged which see human nature as a “work-in-progress, a half-baked beginning that we can learn to remould in desirable ways.”[12] If the term “human” designates our present situation and capacities, we need to reflect how we can become “posthuman”, transcending our biological origins through technology.

We’re all familiar with the way in which we might be able to use selective breeding to “improve” the human race – for example, by breeding out certain genetic deficiencies which make people more prone to disease. Yet there is another option for the transformation of humanity which avoids the social stigma that is now attached to eugenics – namely, the technological enhancement of humanity. The “transhumanist” movement advocates “fundamentally improving the human condition” through technology, thus allowing us to “eliminate ageing and to greatly enhance human intellectual, physical, and psychological capacities.”[13] Through the creation and application of technology, human beings now have the capacity to transcend their biological limits. Yet awkward questions remain. Nick Bostrom, one of the most significant and influential transhumanist philosophers, rightly queries the simplistic equation of technological advances with the notion of progress itself.[14]

Nick Bostrom argues that such judicious technological enhancement of humanity might lead to the emergence of “posthumans” with some or all of the following characteristics.[15]

Individuals could expect to live for more than 500 years;A large section of the population would have cognitive capacities that are more than 2 standard deviations above the present human maximum;Psychological suffering becomes rare.Transhumanists often assume that technological augmentation of natural human cognitive capacities will lead to moral excellence, in effect regarding selfishness and our innate tendencies towards destructive patterns of thought and action as due to mental retardation that will be remedied by boosting our cognitive capacities. It’s an interesting suggestion. Yet its status is that of an unevidenced belief, a charming aspiration, which may lack any grounding in reality. Victor Ferkiss, sometime Professor of Government at Georgetown University, expressed a deep-seated concern a generation ago that has perhaps become even more important today, given the rapid pace of technological development.[16]

Tolkien saw technology as depersonalizing war, making it a battle between machines, with human beings as the main planners and casualties of this new form of warfare. In a 1945 letter to his son Christopher, written in January 1945, during the final stages of the Second World War, Tolkien again lamented the mechanization of war.[17]

Tolkien’s love of Anglo-Saxon literature highlighted the importance of the hero – the individual warrior who showed bravery and honour in face-to-face conflict. How did this relate to the anonymous hail of bullets, which destroyed individuals as a matter of statistical probability, not personal engagement? Tolkien, of course, formed a close personal friendship at Oxford with C. S. Lewis during the 1920s. Their love of classic English literature was one bond between them; another was their experience of the anonymized death of trench warfare. Lewis found himself idealizing the ideas of chivalry, evident in his descriptions of battles in the Chronicles of Narnia. This passage from The Hobbit summarizes Tolkien’s concerns about technology and warfare rather well:[18]

Tolkien here alludes to the use of technology for the purpose of dominating and coercing other wills.[19]

After the Second World War, Bernays tended to see public opinion as inherently dangerous. What happened in Germany under Hitler showed how the views of a society could be harnessed and controlled by a corporate elite, who understood how its ideas could be manipulated, and directed towards benevolent ends. Here’s an extract from his 1928 work Propaganda:[20]

Yet there is evidence that the Nazi rise to power during the 1930s made use of precisely the theories that Bernays had developed in the 1920s, especially in his 1923 work Crystallizing Public Opinion. In his autobiography, Bernay recalls his utter dismay as he heard of how Joseph Goebbels had recognized the importance of his ideas, and used them in bringing about the Nazification of Germany.[21]

Technological enhancements like these are expensive, and their implementation will therefore merely increase global inequality. Those with the financial means will be able to extend their lifespans; everyone else has to continue as normal. The first posthumans may well turn out to be wealthy Americans.A significant expansion of human lifespan immediately raises the concern noted by Thomas Malthus in his Essay on the Principle of Population (1798). Given that the earth has limited resources, it can only sustain a certain number of people. Although Malthus could not have foreseen the development of chemical fertilizers and genetically-modified crops, giving enhanced yields, his point remains valid. Earth’s capacity to produce food limits the size of the population. If human life expectancy rises to 500 years, the overall population must be reduced. Otherwise, the harsh control mechanisms so grimly noted by Malthus – war and famine – would kick in.The assumption that there is a direct correlation between cognitive capacity and moral discernment is contestable. What if technological enhancement merely assists and enables humanity’s seemingly inescapable and utterly irrational tendency to debase and destroy its own best achievements? To use more theological language, does the rise of Transhumanism offer an escape from sin? Or does it make us even more vulnerable to it?None of these questions are easy to answer; yet they all need to be asked. It is far from clear that technological advance will lead us lead to wiser and better decisions than we have made in the recent past. Perhaps that helps us understand why some are suggesting that any possible enhancement of human technological capacity means that we also need a corresponding moral enhancement, if we are to cope with the new challenges that we will inevitably face.[22] But who will reprogramme us? After all, these “moral enhancements” will be developed and chosen by morally questionable human beings, who could easily adapt them to advance their own vested interests and concerns.

But can technological enhancement lead to immortality? Earlier, I mentioned the philosopher John Gray. For Gray, one of the core human obsessions concerns immortality. “Longing for everlasting life, humans show that they remain the death-defined animal.”[23] Yet even those who do not share this fixation on human mortality are obliged to recognize that there are limits placed on our lifespan. We may seek to extend our lives; yet this will simply add further to the stress on our planet’s limited resources, and make war or famine even more likely. So why this anxiety in the first place?

Many answers have been given. The sociologist Peter Berger suggested that human mortality was the ultimate unbearable truth, pointing to the terrifying meaninglessness and chaos which characterized human existence in this world. Society tried to defend and protect people from this unbearable knowledge, shielding them against this terror by asserting the existence of meaning and order in a seemingly meaningless and chaotic universe.[24] Human beings need to be protected by illusions of meaning against this meaningless, chaotic realm of disorder, disintegration and death. J. R. R. Tolkien spoke of human beings spinning “wish-fulfilment dreams” to console and cheat “our timid hearts,” while seeing this human instinct as a sign of some greater horizon that called out to be explored.[25] This human reluctance to accept our own mortality also stood at the heart of Ernest Becker’s Pulitzer Prize winning monograph The Denial of Death (1973). For Becker, human beings are driven by the desire to deny death, transcend it, or create meaning in its face.

History is generous in its benevolent provision of amusing examples to illustrate human attempts to deny, cheat, or conquer death. One of the most entertaining is the attempts made by the Soviet “Immortalization Commission” to preserve Lenin’s body after his death in 1924 – not merely as a potent symbol of the Russian Revolution, but as an assertion of the human capacity to achieve immortality under Marxism-Leninism.[26] Leonid Krasin was an engineer who believed that the dead could be technologically resurrected. Who better than Lenin deserved to be the first to share this privilege? In a series of remarkable experiments, Krasin used refrigeration to preserve Lenin’s body, not merely so that its public display might edify the Soviet masses, but by the demonstration of the Soviet capacity to vanquish death. After all, the Soviet Union arose through the forceful overthrow of imperial Russia. Why not end the tyranny of death in the same way? Christianity talked about the resurrection of the body. Marxism-Leninism could do better than that – it spoke of the technological preservation of the body. It might not amount to the hope of eternal life, but at least it offered the hope of eternal physical preservation.

Now Tolkien’s concerns about technology could easily be dismissed as some form of Luddite reaction against mechanical progress. I take that point. But I cannot help but feel that he raises some important questions about our human future, which we need to consider carefully, especially in the light of the pragmatic attitudes of our culture. Let me bring this lecture to a close by telling you a story that seems to frame these concerns rather well. In 1942, Stanford University in California opened its new School of the Humanities. The celebration of that event was somewhat muted, as the United States was now caught up in a new global conflict, having declared war on Japan, following the bombing of Pearl Harbour in December 1941.[27] John W. Dodds, the first Dean of the School of Humanities, conceded it was not a particularly suitable moment to celebrate human cultural achievements. Why establish “an outpost of the humanities” and talk about the “place of culture in our civilization” when that civilization itself seemed to be teetering on the brink of disaster?[28]

©Professor Alister McGrath, 2017

[1] Caitlin Moran, How to Build a Girl. London: Ebury, 2015, 53.

[2] John Gray, Straw Dogs: Thoughts on Humans and Other Animals. London: Granta, 2002, 29.

[4] Primo Levi, The Black Hole of Auschwitz. Cambridge: Polity, 2005, 4-5.

[5] Louis F. Fieser, “The Synthesis of Vitamin K.” Science 91 (1940): 31-6.

[7] Described in Neer, Napalm, 60.

[8] Loren Eiseley, The Star Thrower. New York: Harcourt Brace & Co., 1978, 267-79.

[9] Eiseley, The Star Thrower, 271.

[10] Eiseley, The Star Thrower, 169-85.

[11] Eiseley, The Star Thrower, 182.

[12] http://www.nickbostrom.com/ethics/values.html

[14] http://www.nickbostrom.com/papers/future.pdf

[15] http://www.nickbostrom.com/papers/future.html

[17] Humphrey Carpenter (ed.), The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981, 111.

[20] Edward Bernays, Propaganda. New York: Liveright, 1928, 27.

[24] Peter Berger, The Sacred Canopy. New York: Doubleday, 1965.

[25] J. R. R. Tolkien, Tree and Leaf. London: HarperCollins, 2001, 87.

[26] For what follows, see Gray, Immortalization Commission, 156-67.

This event was on Tue, 21 Feb 2017

Support Gresham

Gresham College has offered an outstanding education to the public free of charge for over 400 years. Today, Gresham College plays an important role in fostering a love of learning and a greater understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Your donation will help to widen our reach and to broaden our audience, allowing more people to benefit from a high-quality education from some of the brightest minds.

Login

Login